A Comprehensive Guide to In Vitro Immunogenicity Assessment for Peptide-Based Vaccines

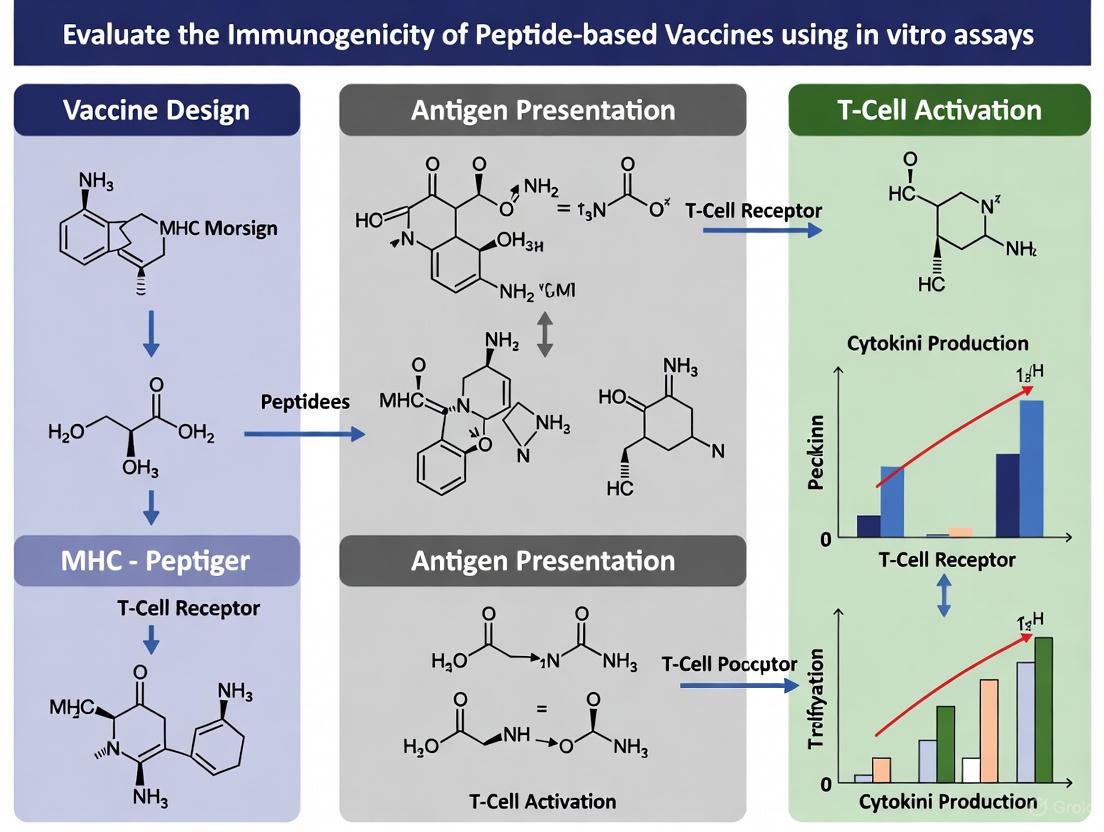

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to evaluate the immunogenicity of peptide-based vaccines using in vitro assays.

A Comprehensive Guide to In Vitro Immunogenicity Assessment for Peptide-Based Vaccines

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to evaluate the immunogenicity of peptide-based vaccines using in vitro assays. It covers the foundational principles of immune responses to peptides, details core methodologies like ELISpot and MHC-binding assays, addresses common challenges in assay optimization and specificity, and outlines strategies for validating results and comparing vaccine candidates. By integrating current regulatory perspectives with advanced technological approaches such as high-throughput immunoarrays and nanoparticle delivery systems, this guide serves as a critical resource for de-risking vaccine development and accelerating the translation of preclinical findings to clinical applications.

Understanding Immunogenicity: Peptide Characteristics and Immune Activation Pathways

In the development of peptide-based therapeutics and vaccines, predicting and controlling immunogenicity is a paramount challenge. Unwanted immune responses can compromise drug efficacy and patient safety, as seen with the investigational drug Taspoglutide, where immunogenicity led to hypersensitivity and injection site reactions, potentially halting its development [1]. The immunogenic potential of a peptide product is not dictated by a single factor but arises from the complex interplay of three core drivers: its origin (whether self or non-self), its amino acid sequence (and resultant structure), and its aggregation potential [2] [3]. For researchers using in vitro assays to evaluate risk, a deep understanding of these drivers and their measurement is essential. This guide provides a comparative overview of these key immunogenic drivers, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant for preclinical assessment.

Peptide Origin: Self, Non-Self, and Modified

The biological origin of a peptide antigen fundamentally shapes its immunogenic profile by determining the pre-existing state of host immune tolerance.

Comparative Immunogenicity of Antigen Types

Table 1: Comparison of Peptide Antigen Types by Origin

| Antigen Type | Origin & Description | Key Example | Immunogenic Potential | Primary Immune Response | Considerations for Vaccine Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor-Associated Antigens (TAAs) | Self-antigens overexpressed on cancer cells (e.g., tissue-specific, germline antigens) | HER2/Neu, gp100, WT1 [3] | Low to Moderate | CD8+ T cells; CD4+ T cells [3] | Limited by central T-cell tolerance; risk of autoimmunity [3] |

| Tumor-Specific Antigens (TSAs) | Non-self antigens unique to tumor cells due to somatic mutations | Neoantigens from KRAS, TP53 [3] | High | CD8+ T cells; CD4+ T cells [3] | Bypasses central tolerance; ideal for personalized vaccines [3] |

| Viral Antigens | Foreign proteins from oncogenic viruses | EBV LMP1/LMP2, HPV E6/E7 [3] | High | CD8+ T cells; CD4+ T cells [3] | Not subject to self-tolerance; strong, specific T-cell responses [3] |

| Fusion Junction Neopeptides | Novel sequences from chimeric RNAs in cancer | KIF5B-RET fusion protein [4] | High | CD8+ T cells [4] | Tumor-specific with low cross-reactivity to normal tissues [4] |

Experimental Analysis of Origin and Immunogenicity

The immunogenicity of non-self origins is clearly demonstrated in studies on fusion neopeptides. Research on the KIF5B-RET fusion junction identified specific 9-mer peptides (e.g., NNDVKEDPK) with high affinity for HLA-C*07:02. In vitro ELISpot assays using HLA-matched donor PBMCs showed that CD8+ T cells from multiple donors responded to these junction peptides, confirming their immunogenic potential. Single-cell RNA sequencing of activated T cells further identified 15 distinct TCR clonotypes, underscoring the ability of these novel sequences to drive a robust and diverse T-cell response [4].

Peptide Sequence and Structure

The amino acid sequence is a primary determinant of immunogenicity, as it dictates both the peptide's affinity for HLA molecules and its potential for chemical degradation.

Sequence-Based Immunogenicity Drivers

- T-cell Epitope Content: The presence of sequences that can bind to HLA class I or II molecules is a prerequisite for T-cell dependent immunogenicity. Impurities in generic peptide drugs that introduce novel HLA-binding sequences not found in the reference product can drive new, unwanted adaptive immune responses [1].

- Amino Acid Substitutions: Specific mutations can significantly enhance HLA-binding. Research on SARS-CoV-2 variants revealed that C>U mutations, which often result in amino acid substitutions like Threonine>Isoleucine (T>I) and Alanine>Valine (A>V), generally increase peptide binding to common HLA-I alleles. This enhanced binding is driven by an increase in peptide hydrophobicity, a property favored by many HLA molecules [5].

- Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): Deamidation, oxidation, and racemization are common PTMs that can occur during manufacturing or storage. These modifications can alter the peptide's structure and create novel epitopes. For instance, software algorithms can sometimes misassign deamidation sites based on MS/MS data, leading to incorrect sequence confirmation and an incomplete understanding of potential immunogenic variants [6].

Experimental Protocol: In Silico Immunogenicity Risk Assessment

A critical first step in sequence analysis is computational screening.

- Objective: To computationally predict the potential of a peptide sequence (API or impurity) to contain T-cell epitopes.

- Method:

- Input: FASTA format sequences of the peptide drug and any known impurities.

- Analysis: Utilize a panel of in silico T cell epitope prediction tools (e.g., NetMHCpan-4.0) to predict binding affinity to a suite of common HLA class I and class II alleles [5] [1].

- Output: Peptides are ranked based on predicted binding affinity (e.g., IC50 values). Impurities are flagged if they contain novel, strong HLA-binding sequences not present in the API or Reference Listed Drug (RLD) [1].

- Application: This orthogonal method is recommended by FDA guidelines for ANDA submissions of generic peptides to evaluate the risk posed by impurities present at 0.1-0.5% of the API [1].

Figure 1: Workflow for In Silico Immunogenicity Risk Assessment. This diagram outlines the computational process for predicting T-cell epitopes in peptide sequences, a key step in evaluating sequence-based immunogenic risk.

Peptide Aggregation and Impurities

Product-related factors such as aggregation and impurities are critical modulators of immunogenicity, capable of converting a otherwise low-risk peptide into a highly immunogenic one.

The Role of Aggregates and Impurities

- Enhancing Innate Immune Activation: Peptide aggregates can act as danger signals, stimulating the innate immune system and creating an inflammatory environment that promotes the breaking of immune tolerance to the peptide drug itself [2] [1].

- Introducing Novel Epitopes: The process of aggregation can expose buried hydrophobic regions or promote chemical degradation (e.g., deamidation, oxidation), leading to the formation of new epitopes [2]. Furthermore, impurities arising from incomplete synthesis (e.g., deletion sequences, truncated products) or side-chain modifications can contain entirely new HLA-binding sequences [1].

Experimental Protocol: MHC-Associated Peptide Proteomics (MAPPs) Assay

To experimentally evaluate how peptide products are processed and presented by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), the MAPPs assay is employed.

- Objective: To identify peptides derived from a therapeutic protein or vaccine that are actually processed and presented on the surface of APCs by HLA-II molecules.

- Method:

- Step 1: Differentiate human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (moDCs) from naive donors.

- Step 2: Pulse the moDCs with the peptide product of interest.

- Step 3: Lyse the cells and immunoaffinity-purify HLA-II/peptide complexes.

- Step 4: Elute and analyze the bound peptides via liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Data Analysis: The identified peptide sequences are mapped back to the drug product to reveal the exact epitopes being presented. This provides a direct, functional readout of the T-cell epitopes that could potentially drive an immune response in vivo [1].

Table 2: Key Impurity Types and Their Immunogenic Potential in Synthetic Peptides

| Impurity Type | Source | Potential Immunogenic Consequence | Control Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Variants | Insertions, deletions, truncations during SPPS [1] | Introduction of novel T-cell epitopes with high HLA-binding affinity [1] | Robust analytical characterization (e.g., HRAM MS) and purification [6] |

| Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs) | Deamidation, oxidation, hydrolysis during manufacturing/storage [2] | Altered peptide structure creating or destroying epitopes; potential for neoepitopes [2] [6] | Control of manufacturing conditions (temp, pH); formulation optimization |

| Aggregates & Fibrils | Physical degradation and self-association [2] [1] | Innate immune activation; provision of T-cell help; enhanced B-cell responses [2] [1] | Monitor via SEC, DLS; optimize formulation excipients |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Assays

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Immunogenicity Assessment

| Reagent/Assay | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | Source of naive T cells and antigen-presenting cells from multiple HLA-typed donors [4] [1] | In vitro T-cell activation assays (ELISpot); dendritic cell priming assays |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Spot (ELISpot) | Quantify antigen-specific T-cell responses (e.g., IFN-γ release) at the single-cell level [4] | Measuring T-cell activation in response to peptide antigens or impurities |

| HLA-I and HLA-II Tetramers | Directly identify and isolate T cells with specificity for a given peptide-HLA complex [3] | Tracking the frequency and phenotype of antigen-specific T cells pre- and post-vaccination |

| Toll-Like Receptor (TLR) Agonists (e.g., Poly-ICLC) | Potent adjuvants that activate dendritic cells via TLR3 and MDA5 pathways [7] | Enhancing the immunogenicity of peptide vaccines in preclinical models and clinical trials |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry | Precisely characterize peptide sequence, PTMs, and impurities [6] | Peptide mapping for identity confirmation; detecting and quantifying product-related variants |

| 3,6-Dihydroxyflavone | 3,6-Dihydroxyflavone|High-Purity Research Compound | |

| 6-Methoxywogonin | 6-Methoxywogonin, CAS:3162-45-6, MF:C17H14O6, MW:314.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

A systematic, multi-faceted approach is essential for accurately profiling the immunogenic risk of peptide-based products. The three drivers—origin, sequence, and aggregation—are not independent; a peptide with a low-risk self-origin can become immunogenic if its sequence is prone to aggregation or degradation into impurity forms containing novel T-cell epitopes. Therefore, a robust immunogenicity risk assessment strategy must integrate orthogonal methods: in silico tools for initial sequence screening, advanced analytical techniques (HRAM MS) for impurity and PTM detection, and functional in vitro assays (MAPPs, ELISpot) using primary human immune cells to confirm biological presentation and response. By systematically evaluating these key drivers, researchers can de-risk development pipelines and design safer, more effective peptide-based vaccines and therapeutics.

The adaptive immune system mounts a highly specific response against pathogens, primarily orchestrated by B and T lymphocytes. While both cell types are essential for immunological protection, they recognize antigens through fundamentally distinct mechanisms. B cells identify native antigens via B cell receptors (BCRs), while T cells recognize processed peptide fragments presented by Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) [8] [9]. These differences in recognition underlie specialized roles in humoral and cell-mediated immunity. Understanding the precise mechanisms of HLA presentation and antibody production is crucial for developing effective peptide-based vaccines and evaluating immunogenicity through in vitro assays [8] [10]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of T-cell and B-cell epitopes, detailing their characteristic features, experimental identification methods, and implications for vaccine design.

Core Biological Differences: A Comparative Framework

The table below summarizes the fundamental biological distinctions between T-cell and B-cell epitopes that determine their respective roles in adaptive immunity.

Table 1: Fundamental Biological Characteristics of T-cell and B-cell Epitopes

| Characteristic | T-cell Epitopes | B-cell Epitopes |

|---|---|---|

| Recognizing Lymphocyte | T lymphocytes (CD4+ helper, CD8+ cytotoxic) [11] [12] | B lymphocytes [11] |

| Native Structure Recognition | Recognizes processed linear peptides [9] | Recognizes intact, conformational, or linear epitopes on native antigens [8] |

| MHC/HLA Restriction | Strictly requires MHC presentation (Class I for CD8+, Class II for CD4+) [8] [9] | No MHC restriction for initial recognition [8] |

| Typical Epitope Size | MHC-I: 8-11 amino acids [8]MHC-II: 13-25 amino acids (core 9 aa bound) [8] [9] | 5-15 amino acids (conformational or linear) [8] |

| Chemical Nature | Primarily proteins (processed peptides) [8] | Proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, nucleic acids [8] |

| Epitope Location | Hidden, internal linear sequences [8] | Solvent-exposed regions of the antigen [8] |

Structural Basis of Epitope Presentation and Recognition

T-cell Epitopes and MHC Restriction

T-cell epitopes are short peptides derived from proteolytic processing of protein antigens, presented by MHC molecules on the surface of APCs. The MHC binding groove structure dictates key differences between Class I and Class II presentation [8].

MHC Class I Presentation: The peptide-binding cleft is closed at both ends, accommodating shorter peptides (typically 9-11 amino acids). The N- and C-terminal are anchored by conserved hydrogen bonds to the MHC molecule. Deep binding pockets with tight physicochemical preferences facilitate relatively accurate binding predictions [8].

MHC Class II Presentation: The peptide-binding groove is open, allowing bound peptides to extend beyond the groove. This accommodates longer peptides (typically 13-25 amino acids), with only a core of nine residues sitting within the binding groove. Shallower, less demanding binding pockets make peptide-MHC II binding prediction less accurate compared to MHC I [8].

B-cell Epitopes and Direct Recognition

B-cell epitopes constitute the specific region of an antigen that binds to an immunoglobulin or antibody. These epitopes are typically solvent-exposed regions and can be of diverse chemical nature, including proteins, polysaccharides, and lipids [8]. Unlike T-cells, B-cells recognize antigens in their native, three-dimensional conformation without a requirement for antigen processing or MHC presentation [8] [11]. B-cell epitopes can be conformational (dependent on the tertiary structure of the antigen) or linear (sequential amino acids) [8].

Figure 1: Divergent Antigen Recognition Pathways. T-cells require antigen processing and MHC presentation, while B-cells recognize native antigen structures directly.

Experimental Methods for Epitope Identification

Epitope mapping is crucial for understanding disease etiology, immune monitoring, and vaccine design [8]. The table below compares established experimental protocols for identifying T-cell and B-cell epitopes.

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Epitope Identification and Characterization

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Readout | Utility in Vaccine Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-cell Epitope Mapping | ELISPOT [8], MHC Multimers [8], Intracellular Cytokine Staining, Lymphoproliferation Assays [8] | T-cell activation, cytokine secretion, proliferation | Identifies immunogenic peptides for inclusion in vaccines to stimulate cellular immunity |

| B-cell Epitope Mapping | X-ray Crystallography (Ag-Ab complexes) [8], Peptide Library Screening [8], Phage Display, Mutational Analysis [8] | Antibody binding to antigenic regions | Defines targets for neutralizing antibodies; guides reverse vaccinology |

Detailed Protocol: ELISPOT for T-cell Epitope Immunogenicity

The Enzyme-Linked Immunospot (ELISPOT) assay is a sensitive method for quantifying antigen-specific T cells based on their cytokine secretion [8].

Workflow:

- Plate Coating: A 96-well plate with a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane is coated with a primary capture antibody against a specific cytokine (e.g., IFN-γ for CD8+ T cells, IL-4/IL-5 for CD4+ Th2 cells).

- Cell Seeding and Stimulation: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or purified T cells are plated at varying densities alongside the test peptides (candidate epitopes). Positive control (e.g., phytohemagglutinin) and negative control (no peptide) wells are included.

- Incubation: Cells are incubated for 24-48 hours. During this time, activated T cells secrete cytokine, which is captured by the surrounding antibody.

- Detection: Cells are removed, and a biotinylated secondary detection antibody is added, followed by an enzyme-conjugated streptavidin (e.g., alkaline phosphatase or horseradish peroxidase).

- Spot Development: A precipitating substrate is added, producing colored spots at the sites of cytokine capture. Each spot represents a single reactive T cell.

- Analysis: Spots are counted using an automated ELISPOT reader. The frequency of antigen-specific T cells is calculated as spot-forming units (SFU) per million input cells. A response is typically considered positive if it significantly exceeds the negative control (e.g., 2-fold increase and >50 SFU/million).

Detailed Protocol: Peptide Library Screening for B-cell Epitopes

This method identifies linear B-cell epitopes by screening overlapping peptides derived from the antigen sequence against antisera or monoclonal antibodies.

Workflow:

- Peptide Synthesis: A library of synthetic peptides (typically 12-15 amino acids long with an overlap of 5-10 residues) spanning the entire protein sequence is synthesized on a cellulose membrane (SPOT synthesis) or in 96-well plates.

- Membrane Blocking: The membrane is incubated with a blocking buffer (e.g., 5% bovine serum albumin in TBST) to prevent non-specific antibody binding.

- Antibody Probing: The membrane is probed with the primary antibody (patient sera, monoclonal antibody) diluted in blocking buffer.

- Washing and Detection: Unbound antibody is washed away, and a labeled secondary antibody (e.g., horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-human IgG) is added.

- Signal Visualization: A chemiluminescent or colorimetric substrate is used to visualize the bound antibodies. Positive reactions appear as spots or colored wells corresponding to reactive peptides.

- Epitope Mapping: The amino acid sequences of the reactive peptides are aligned to define the minimal linear epitope core.

In Silico Prediction Tools and Computational Approaches

Traditional epitope identification is costly and time-consuming. In silico prediction methods dramatically reduce the experimental burden by prioritizing candidates for validation [8]. These tools are indispensable for rational vaccine design.

Table 3: Computational Tools for Epitope Prediction

| Tool Name | Prediction Target | Methodology | URL/Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| SYFPEITHI [8] | MHC-I & MHC-II binding | Motif/Matrix-based (MM) | http://www.syfpeithi.de/ |

| Rankpep [8] | MHC-I & MHC-II binding | Motif/Matrix-based (MM) | http://imed.med.ucm.es/Tools/rankpep.html |

| EpiDOCK [8] | MHC-II binding | Structure-Based (SB) | http://epidock.ddg-pharmfac.net |

| MHCPred [8] | MHC-I & MHC-II binding | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) | http://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/mhcpred/MHCPred/ |

| BIMAS [8] | MHC-I binding | Quantitative Affinity Matrix (QAM) | https://www-bimas.cit.nih.gov/molbio/hla_bind/ |

Figure 2: Computational Epitope Prediction Workflow. In silico tools use data-driven or structure-based approaches to predict T-cell and B-cell epitopes from antigen sequences, streamlining experimental validation.

This section details key reagents and tools essential for conducting epitope mapping and immunogenicity studies in vitro.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Epitope and Immunogenicity Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Peptides | Short amino acid sequences (typically >70% purity) representing potential epitopes. | T-cell activation assays (ELISPOT), peptide library screens for B-cell epitope mapping [8]. |

| MHC Multimers (Tetramers, Dextramers) | Fluorescently labeled MHC-peptide complexes for staining antigen-specific T cells. | Flow cytometric identification, enumeration, and isolation of epitope-specific T cells [8]. |

| Recombinant Proteins | Purified, full-length or truncated antigen proteins. | B cell activation studies, antibody binding assays (ELISA), source material for antigen processing studies. |

| Cytokine-Specific Capture Antibodies | High-affinity antibodies for specific cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-17, etc.). | ELISPOT and intracellular cytokine staining to quantify functional T-cell responses [8]. |

| Fluorochrome-conjugated Anti-Human Ig | Antibodies targeting human immunoglobulin isotypes (IgG, IgA, IgM) and subclasses (IgG1-4). | Flow cytometry for B cell phenotyping, ELISA for measuring isotype-switched antibody responses [13]. |

| TLR Agonists (e.g., MPLA) | Toll-like receptor ligands used as adjuvants. | Mimic pathogen-associated molecular patterns to provide co-stimulatory signals in in vitro B cell activation models [14]. |

| In Silico Prediction Tools | Software and web servers for computational epitope prediction. | Prioritizing candidate T-cell and B-cell epitopes for experimental validation, reducing time and cost [8] [15]. |

Implications for Peptide-Based Vaccine Design

The distinct mechanisms of epitope recognition directly inform the rational design of peptide-based vaccines. A critical consideration is the coordinated engagement of both B and T cell arms of the immune system.

Engaging T-cell Help for B Cell Responses

For most protein antigens, robust and high-affinity antibody responses require CD4+ T cell help, which is a T-cell dependent (TD) response [15]. In this pathway:

- B cells internalize the antigen bound to their BCR, process it, and present derived peptides on MHC class II molecules.

- Cognate CD4+ helper T cells recognize this peptide-MHC complex and provide co-stimulatory signals (e.g., CD40L, cytokines) to the B cell.

- This help drives B cell proliferation, immunoglobulin class switching from IgM to IgG, IgA, or IgE, and affinity maturation in germinal centers, leading to memory B cell and long-lived plasma cell formation [15].

The Challenge of Immunodominance

A significant hurdle in designing universal vaccines against viruses like HIV and influenza is immunodominance, where responses focus on a few dominant, often variable epitopes at the expense of subdominant, conserved epitopes targeted by broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) [10]. Recent theories, such as the "immunodominance relativity" theory, suggest that the physical positioning of B and T cell epitopes within the antigen matters. Antibody binding can enhance the presentation of adjacent CD4+ T cell epitopes while suppressing the presentation of overlapping ones. In several pathogens, conserved B cell epitopes targeted by bnAbs overlap with clusters of dominant CD4+ T cell epitopes, potentially putting B cells bearing bnAbs at a competitive disadvantage in germinal centers [10]. Strategic epitope engineering to disrupt these unfavorable overlaps or to create new, favorable B-T epitope partnerships could be key to guiding the immune system toward desired bnAb responses.

T-cell Independent B Cell Activation

Emerging evidence also reveals that under specific conditions, such as with highly dense, repetitive antigen arrays presented on liposomes with a TLR4 agonist like MPLA, B cells can be activated in a T-cell independent (TI) manner [14]. This pathway can induce rapid IgG class switching, germinal center formation, and long-lived memory, characteristics previously attributed solely to TD responses [14]. This knowledge opens avenues for designing vaccines that can elicit rapid and potent antibody responses even in individuals with compromised T-cell immunity.

The immunogenicity of peptide-based products—encompassing therapeutics, subunit proteins, and vaccines—is a critical determinant of their safety and efficacy. Unlike small molecule drugs, these biologics are susceptible to eliciting unwanted immune responses, which can range from reduced therapeutic effectiveness to severe adverse effects. This immunogenic potential is not solely an inherent property of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) but is profoundly influenced by product-related factors, including impurities, structural modifications, and the presence of adjuvants [2] [1]. For peptide-based vaccines, the careful incorporation of adjuvants is essential to enhance immunogenicity, whereas for therapeutic peptides, their presence is undesirable [16] [17]. A thorough understanding and control of these factors through advanced in vitro assays is therefore paramount for the rational design and regulatory approval of peptide-based products, ensuring they achieve their desired immunological outcome without compromising safety [18] [19].

Impact of Impurities on Immunogenicity

Peptide-related impurities are undesirable chemical components that can be introduced during synthesis, manufacturing, or storage. In Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS), the industry standard for peptides under 40 amino acids, impurities arise from incomplete reactions or side processes [2] [1]. For recombinant peptides, process-related impurities like host cell proteins are a greater concern [2]. The table below classifies common impurities and their immunogenicity risks.

Table 1: Types and Immunogenic Risks of Peptide Impurities

| Impurity Category | Specific Examples | Source | Potential Immunogenic Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product-Related | Amino acid deletions, insertions, truncations | SPPS process | Introduction of novel T-cell epitopes [1]. |

| D-stereoisomer incorporation | SPPS process | Potential structural changes leading to new immune recognition. | |

| Post-Synthetic Modifications | Deamidation, oxidation, disulfide bond breakage | Manufacturing and storage | Altered peptide structure and potential neo-epitope formation [2]. |

| Process-Related | Host Cell Proteins (HCPs), DNA | Recombinant expression systems | Can act as adjavants, activating innate immunity [2]. |

| Aggregates & Fibrils | Oligomers, higher-order structures | Formulation and storage | Can enhance B-cell and T-cell responses by repetitive antigen display [2] [1]. |

Mechanisms of Immunogenicity

Impurities can drive immunogenicity through two primary, interconnected mechanisms: adaptive immune response and innate immune activation.

Adaptive Immune Response: Peptide impurities may contain sequences that are efficiently presented by Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules, particularly HLA Class II, to CD4+ T-cells [1]. The activation of naive T-cells is a critical step for providing help to B-cells, leading to the production of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) [1]. Even minor sequence variations in an impurity, such as a single amino acid substitution, can create a novel T-cell epitope that was not present in the API, breaking immune tolerance and initiating an unwanted adaptive immune response [1].

Innate Immune Activation (IIRMI): Trace impurities can function as Innate Immune Response Modulating Impurities (IIRMI). These substances act as inadvertent adjuvants by activating Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like Receptors (TLRs), on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) like dendritic cells and monocytes [18] [19]. This activation triggers inflammatory signaling pathways, leading to the upregulation of costimulatory molecules and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This process creates a local immunogenic environment that promotes the activation of antigen-specific T-cells, thereby increasing the risk of an adaptive immune response against the peptide drug itself [18].

The following diagram illustrates the signaling pathways through which IIRMI trigger innate immune activation, a key mechanism in adjuvant function.

Experimental Assays for Detecting Impurity-Related Immunogenicity

Robust in vitro assays are essential for quantifying the immunogenic risk posed by impurities. Regulatory guidance for generic peptides recommends using orthogonal methods to provide independent lines of evidence [1].

Table 2: Key Assays for Immunogenicity Risk Assessment of Impurities

| Assay Type | Methodology Overview | Key Readouts | Application & Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Silico Epitope Prediction | Computational screening of peptide sequences for predicted binding affinity to a panel of common HLA-DR alleles [1]. | Binding score, % Rank. | Early risk assessment; identifies impurities with high potential to contain novel T-cell epitopes [1]. |

| In Vitro T-cell Assay | Co-culture of naive T-cells from diverse human donors with APCs pulsed with the impurity or API [1]. | T-cell proliferation (e.g., by CFSE), cytokine secretion (e.g., IFN-γ). | Functional assessment of naive T-cell activation; compares impurity to API [1]. |

| Cell-Based IIRMI Assay | Exposure of reporter cell lines (e.g., THP-1, RAW-Blue) or human PBMCs to the product [18] [19]. | NF-κB activation (SEAP), gene expression (IL-1β, IL-6, CCL3) via qPCR. | Detects innate immune activation potential of impurities; assesses overall adjuvant effect [18] [19]. |

Detailed Protocol: Cell-Based IIRMI Assay [18] [19]

- Cell Model: THP-1-Blue cells (human monocyte line with an NF-κB/AP-1-inducible SEAP reporter) or primary human PBMCs from healthy donors.

- Stimulation: Cells are plated and stimulated with the test article (API with impurities), a negative control (vehicle), and positive controls (known PRR agonists like LPS for TLR4) for 24 hours.

- Culture Conditions: Optimization is critical, as product excipients can sometimes mask immune responses [19]. A typical drug product concentration of 1-10 IU/mL can be used.

- Readout: SEAP activity in the supernatant is measured colorimetrically using Quanti-Blue detection medium. Viability is assessed in parallel using a reagent like CCK-8.

- Data Analysis: Results are compared to the reference listed drug (RLD) to determine if the test product elicits a significantly stronger innate immune response.

Impact of Structural and Chemical Modifications

Types of Modifications

Structural modifications are often deliberately introduced to improve the stability and pharmacokinetic profile of therapeutic peptides, but they can inadvertently alter immunogenicity.

Table 3: Impact of Common Peptide Modifications on Immunogenicity

| Modification Type | Purpose | Impact on Immunogenicity |

|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Substitution (Unnatural) | Enhance metabolic stability, receptor affinity. | May create novel T-cell epitopes if the new residue improves binding to HLA [2] [1]. |

| Peptide Cyclization | Conformational restraint, protease resistance. | Can better mimic native protein epitopes, potentially enhancing desired immune responses for vaccines [17]. |

| Pegylation | Increase hydrodynamic size, reduce renal clearance. | Can shield immunogenic epitopes, but the PEG polymer itself can be immunogenic [2]. |

| Glycosylation | Improve solubility and stability. | Alters peptide structure; the glycan moiety can be recognized by immune cells [2]. |

Case Study: The Taspoglutide Incident

The development of the GLP-1 analog Taspoglutide provides a cautionary tale. During Phase 3 trials, a high incidence of systemic hypersensitivity reactions and injection-site reactions was observed [1]. Subsequent investigation linked these adverse events to the development of anti-drug antibodies. Retrospective studies suggested that sequence impurities introduced during synthesis were the likely culprit. These impurities contained sequences that were presented by specific HLA-DR alleles and activated T-cells in a subset of patients, leading to the adaptive immune response and clinical immunogenicity [1]. This case underscores the critical need for stringent impurity control and immunogenicity assessment.

Impact of Adjuvants in Peptide-Based Vaccines

The Role of Adjuvants

In contrast to therapeutic peptides where immunogenicity is undesirable, peptide-based vaccines often require adjuvants to be effective. Peptide antigens alone are typically poorly immunogenic as they lack the innate immune activation provided by whole pathogens [17] [20]. Adjuvants, which are components included in vaccine formulations, enhance the magnitude, breadth, and durability of the adaptive immune response [16] [17]. They function by activating innate immunity, mimicking the "danger signal" of an infection, which leads to enhanced antigen presentation and T-cell activation, as illustrated in the pathway diagram in Section 2.2.

Comparing Adjuvant Platforms and Formulations

Recent research focuses on novel adjuvant formulations and delivery systems to maximize immune responses against peptide antigens.

Table 4: Comparison of Adjuvant Platforms for Peptide Vaccines

| Adjuvant Platform | Composition / Key Molecule | Proposed Mechanism of Action | Reported Efficacy (Model) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR4 Agonist Formulations [16] | EmT4, LiT4Q (Liposomal), AlT4 (Alum-adsorbed). | Activation of TLR4 signaling pathway, leading to robust NF-κB-driven cytokine production. | Significantly boosted antibody breadth against SARS-CoV-2 variants (Omicron) when used as a protein boost after an RNA prime in mice [16]. |

| Nanotechnology-Based Systems [20] | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), polymer-based nanoparticles. | Protects antigen, enhances drainage to lymph nodes, promotes co-delivery of antigen and adjuvant to APCs. | Improves cross-presentation for CD8+ T-cell activation, critical for cancer vaccines; enhances stability of peptide antigens [20]. |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) [21] | Self-assembling structural proteins lacking viral genome. | Presents a repetitive, high-density antigen array to B-cells; can have built-in PAMP activity. | Demonstrated higher protection (RR=1.66) in an FMDV vaccine meta-analysis compared to peptide vaccines [21]. |

Detailed Protocol: Evaluating Adjuvant Efficacy In Vivo [16]

- Vaccination Regimen: Mice are primed with an antigen (e.g., RNA vaccine or protein) and later boosted with the peptide antigen formulated with the test adjuvant. Control groups receive antigen alone or with a known adjuvant.

- Immunogenicity Assessment:

- Humoral Response: Serum is collected periodically and analyzed by ELISA to measure antigen-specific IgG titers. A pseudovirus neutralization assay can evaluate functional antibody responses.

- Cellular Response: Splenocytes are isolated and re-stimulated with the antigen to measure T-cell responses via ELISpot (for IFN-γ) or intracellular cytokine staining.

- Analysis: The strength and breadth of the immune response against the target pathogen or variants are compared between adjuvant groups.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key reagents and their functions for conducting immunogenicity assays as discussed in this guide.

Table 5: Key Reagents for Immunogenicity and Vaccine Research

| Research Reagent / Assay | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| THP-1-Blue Cells | Reporter cell line for detecting NF-κB/AP-1 activation via SEAP. | Screening for IIRMI in drug products and impurities [18] [19]. |

| RAW-Blue Cells | Mouse macrophage reporter cell line for NF-κB/AP-1 activation. | Orthogonal model for innate immune activation studies [19]. |

| Quanti-Blue | SEAP detection substrate. Colorimetric readout for NF-κB activation in reporter assays [18]. | |

| Primary Human PBMCs | Provide a diverse, physiologically relevant immune cell population. | Comprehensive in vitro immunogenicity testing [18]. |

| TLR Agonists (e.g., LPS, FSL-1) | Positive control ligands for specific PRR pathways. | Assay validation and as model IIRMIs [18] [19]. |

| HLA Typing Kits | Determine the HLA allele composition of human donor cells. | Stratify T-cell assay results by HLA type for risk assessment [1]. |

| ELISpot Kits (e.g., IFN-γ) | Quantify antigen-specific T-cell responses at the single-cell level. | Evaluating cellular immunogenicity of vaccine formulations [16]. |

| T-1330 | T-1330, CAS:106461-41-0, MF:C22H27N5O2, MW:393.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Hydroxy Atorvastatin Lactone-d5 | 2-Hydroxy Atorvastatin Lactone-d5, CAS:265989-50-2, MF:C33H33FN2O5, MW:561.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The immunogenicity of peptide-based products is a complex trait heavily influenced by product-related factors. Impurities, even at trace levels, can introduce novel T-cell epitopes or act as adjuvants, driving unwanted adaptive immune responses. Conversely, deliberate structural modifications can either enhance or diminish immunogenicity, requiring careful evaluation. For peptide vaccines, the strategic use of adjuvants is non-negotiable for achieving protective immunity. The evolving regulatory landscape, particularly for generic and follow-on products, emphasizes the critical role of advanced in vitro models—including in silico tools, cell-based IIRMI assays, and in vitro T-cell assays—in assessing immunogenicity risk. Mastering the control and characterization of these product-related factors is essential for developing safer, more effective peptide-based therapeutics and vaccines.

Immunogenicity—the unwanted propensity of a therapeutic product to provoke an immune response—is a critical parameter in drug development, influencing both the safety and efficacy of biopharmaceuticals [22]. For peptide-based vaccines and therapeutics, assessing this risk is a multifaceted challenge that spans the entire drug development lifecycle, from candidate selection to post-marketing surveillance [2]. The global market for therapeutic peptides is projected to grow rapidly, reaching US$86.9 billion by 2032, intensifying the need for robust immunogenicity assessment frameworks [2]. This guide objectively compares the experimental approaches and regulatory considerations for immunogenicity risk assessment, providing researchers with a detailed comparison of methodologies, their applications, and supporting data.

Regulatory Framework and Lifecycle Approach

Regulatory guidance emphasizes an integrated risk assessment strategy where immunogenicity is evaluated at every stage of development [2] [22]. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) both require immunogenicity assessment for therapeutic proteins and peptides, with reporting under ‘adverse effects’ in drug labeling [22]. A significant regulatory gap exists for follow-on therapeutic peptide products; specifically, "broadly applicable impurity qualification thresholds are not available for peptide drug products," and controls are established on a case-by-case basis [2]. For chemical peptides, principles from ICH Q3A and Q3B may be considered, while recombinant peptides fall under ICH Q6B, though none provide specific acceptance criteria for impurities [2].

Table 1: Immunogenicity Risk Factors Throughout the Drug Lifecycle

| Development Stage | Primary Risk Factors | Key Assessment Methods | Regulatory Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate Selection | Sequence similarity to self-proteins, intrinsic immunogenic epitopes [2] | In silico T-cell epitope prediction, in vitro MHC binding assays [2] [22] | Justification of candidate sequence based on predicted low immunogenic potential [22] |

| Manufacturing | Process-related impurities, peptide-related impurities (e.g., deletions, substitutions), aggregates, host cell proteins [2] | Analytical characterization (SEC, MALS, DLS, MFI), accelerated stability studies [2] [22] | Control strategies for impurities and aggregates; case-by-case justification for synthetic peptide impurities [2] |

| Pre-clinical | Immunotoxicity, innate immune activation, breaking of immune tolerance [2] | GLP toxicology studies in relevant species, immune monitoring for ADA [2] [22] | Species relevance is critical; data used to flag potential clinical risks [22] |

| Clinical Stage | Patient factors (genetics, disease), treatment factors (dose, route), product quality [2] | Validated anti-drug antibody (ADA) assays, PK/PD impact assessment, safety monitoring [2] [22] | FDA & EMA require clinical immunogenicity testing and reporting of ADA incidence and impact [22] |

| Post-Marketing | Rare immune-related adverse events [2] | Phase IV studies, pharmacovigilance systems [2] | Monitoring for rare events not captured in clinical trials [2] |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated immunogenicity risk assessment process across the drug development lifecycle, incorporating both forward and reverse translational approaches [22].

Diagram 1: Immunogenicity Risk Assessment Workflow

In Vitro Assays for Immunogenicity Risk Assessment

A suite of in vitro assays is employed to predict and measure immunogenic potential, especially before clinical studies. These assays evaluate the innate and adaptive immune system activation potential of peptide products and their impurities.

Key Assay Methodologies and Protocols

Dendritic Cell (DC) Activation Assay

- Objective: To assess the potential of a peptide product or impurity to activate dendritic cells, a critical step in initiating an adaptive immune response [22].

- Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Isolate human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (moDCs) from healthy donor PBMCs using CD14+ magnetic beads. Differentiate monocytes in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with GM-CSF (50 ng/mL) and IL-4 (20 ng/mL) for 5-7 days [22].

- Stimulation: Harvest immature DCs and seed in 96-well plates. Expose cells to the peptide product, relevant impurities (e.g., aggregates, oxidized species), or controls (LPS as positive control, culture medium as negative control) for 24 hours.

- Analysis: Harvest supernatant for cytokine analysis (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, IL-12p70) via ELISA or multiplex immunoassay. Analyze cells by flow cytometry for surface activation markers (e.g., CD80, CD83, CD86, HLA-DR) [22].

- Data Interpretation: A statistically significant increase in cytokine secretion and/or surface marker expression compared to the negative control indicates innate immune activation and higher immunogenic potential.

T-Cell Activation Assay (ELISpot/T-Cell Proliferation)

- Objective: To measure the activation and proliferation of peptide-specific T-cells, which drive adaptive cellular immunity [22].

- Protocol:

- PBMC Isolation: Isolate PBMCs from multiple healthy human donors using density gradient centrifugation (e.g., Ficoll-Paque). The use of donors with diverse HLA types is critical for a representative assessment [22].

- Culture and Stimulation: Seed PBMCs in 96-well plates. Add the peptide product, its fragments, or positive controls (e.g., PHA). For IFN-γ ELISpot, use pre-coated plates. For proliferation assays, use CFSE staining tracked by flow cytometry.

- Incubation: Culture cells for 5-7 days in a CO₂ incubator at 37°C.

- Detection (ELISpot): Develop plates according to manufacturer's instructions after adding detection antibodies. Spot-forming units (SFUs) are counted using an automated ELISpot reader [22].

- Data Interpretation: An increase in IFN-γ SFUs or CFSE-dim T-cells in test wells compared to negative control wells indicates a T-cell response.

MHC-Associated Peptide Proteomics (MAPPs) Assay

- Objective: To identify specific peptides from a biotherapeutic that are processed by DCs and presented on MHC class II molecules, directly characterizing the potential T-cell epitope repertoire [22].

- Protocol:

- Pulse DCs with Antigen: Immature human DCs are pulsed with the peptide product for 24-48 hours.

- MHC Peptide Complex Isolation: Lyse cells and immunoprecipitate HLA-DR molecules using a specific antibody.

- Peptide Elution and Analysis: Elute bound peptides from the MHC complex and identify them by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [22].

- Data Interpretation: The presence of peptide sequences derived from the drug product in the MHC-II immunoprecipitate confirms their presentation to T-cells. Sequences with high abundance or similarity to known immunogenic epitopes pose a higher risk.

Comparative Analysis of In Vitro Assays

Table 2: Comparison of Key In Vitro Immunogenicity Assays

| Assay Type | Measured Endpoint | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Readout | Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC Activation Assay | Innate immune activation; DC maturation markers & cytokine release [22] | Detects innate immune danger signals; high sensitivity to aggregates and impurities [22] | Does not directly measure T-cell activation; donor variability [22] | Cytokine concentration (pg/mL); % CD86+ cells | High for innate immunogenicity |

| T-Cell Assay (ELISpot) | Antigen-specific T-cell response (e.g., IFN-γ production) [22] | Directly measures adaptive T-cell response; uses human PBMCs [22] | Requires donor pools with diverse HLA; may lack sensitivity for low-frequency T-cells [22] | Spot-forming units (SFU) per million cells | Moderate to high for cellular immunogenicity |

| MAPPs Assay | Peptide sequences presented on MHC class II [22] | Directly identifies potential T-cell epitopes; highly informative for sequence optimization [22] | Technically complex and expensive; requires expertise in LC-MS/MS [22] | Peptide sequences and abundance | High for de-risking T-cell responses |

| NF-κB Reporter Assay | TLR pathway activation (e.g., TLR4) [16] | High-throughput; specific for TLR-mediated immunogenicity [16] | Limited to specific pathways; may not reflect full cellular context [16] | Luminescence or fluorescence units | Moderate for specific TLR engagement |

The relationship between these assays and the immunological pathways they probe is complex. The following diagram outlines the core immunogenicity pathway and the points where key in vitro assays provide critical data.

Diagram 2: Immunogenicity Pathways and Assay Targets

Case Study: Peptide-Based Vaccines

Peptide-based vaccines, such as those developed for Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus (FMDV), provide compelling real-world data on immunogenicity assessment. A systematic review and meta-analysis of FMDV vaccines (2020-2025) compared the protective efficacy of different platforms [21].

Table 3: Meta-Analysis of FMDV Vaccine Efficacy (2020-2025) [21]

| Vaccine Platform | Pooled Risk Ratio (RR) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virus-Like Particle (VLP) | 1.66 | 0.97 – 2.86 | Higher protection, wide CI indicates variability [21] |

| Viral Vector | 1.90 | 0.08 – 46.65 | Highest point estimate, but very wide CI [21] |

| Peptide-Based | 1.09 | 0.75 – 1.57 | Moderate efficacy [21] |

| Dendritic Cell-Based | Not Significant | Not Significant | Limited demonstrable benefit [21] |

A specific FMDV peptide vaccine, the Bâ‚‚T-TBâ‚‚ dendrimer, demonstrates how rational design mitigates immunogenicity risks while ensuring efficacy. This multiepitopic platform incorporates four copies of a VP1 B-cell epitope and two copies of a 3A T-cell epitope from FMDV, assembled via chemoselective "click" chemistry (thiol-ene and CuAAC) [23].

- Experimental Protocol for Challenge Study:

- Vaccination: Domestic pigs (natural FMDV host) were immunized with a single low dose (0.5 mg) of either Bâ‚‚T-TBâ‚‚ or its predecessor B2T, formulated with adjuvant [23].

- Immune Monitoring: Serum was collected periodically to measure FMDV-neutralizing antibody titers via virus neutralization test. T-cell responses were assessed by IFN-γ ELISpot upon stimulation with the T-cell epitope [23].

- Challenge: At 25 days post-immunization (dpi), pigs were intradermally challenged with FMDV O-UK/11/2001. Animals were monitored daily for clinical signs (vesicular lesions on snout and feet) and viremia was tracked by RT-qPCR [23].

- Results: A single low dose of Bâ‚‚T-TBâ‚‚ induced a rapid and robust neutralizing antibody response and protected 100% of swine (no clinical signs post-challenge), outperforming the already effective B2T prototype and confirming that well-defined peptide vaccines can achieve high levels of protection without unwanted immunopathology [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Immunogenicity Assessment | Specific Example / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Human PBMCs from Diverse Donors | Provides a genetically diverse human immune cell source for in vitro T-cell and DC assays [22] | Used in ELISpot and DC activation assays to account for HLA polymorphism [22] |

| Magnetic Cell Separation Kits | Isolation of specific immune cell populations (e.g., CD14+ monocytes) from PBMCs for defined assays [22] | Differentiation of CD14+ monocytes into Dendritic Cells for DC activation studies [22] |

| Recombinant Human Cytokines | Differentiation and maintenance of primary immune cells in culture [22] | GM-CSF and IL-4 for generating monocyte-derived Dendritic Cells (moDCs) [22] |

| ELISpot Kits (e.g., IFN-γ) | Detection and quantification of antigen-specific T-cell responses at the single-cell level [22] | Measuring T-cell responses to peptide antigens in PBMC cultures [23] [22] |

| TLR Agonist Adjuvants | Positive controls for innate immune activation assays; components in vaccine formulations [16] | EmT4TM, LiT4QTM (TLR4 agonists) used as adjuvants and controls [16] |

| Click Chemistry Reagents | Modular, chemoselective conjugation for constructing defined multi-epitope peptide vaccines [23] | Synthesis of Bâ‚‚T-TBâ‚‚ dendrimer vaccine via CuAAC and thiol-ene reactions [23] |

| 5-Nitrouracil | 5-Nitrouracil CAS 611-08-5|Research Chemical | |

| Rsu 1164 | Rsu 1164, CAS:105027-77-8, MF:C10H16N4O3, MW:240.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

A proactive and integrated immunogenicity risk assessment strategy is paramount for developing safe and effective peptide-based drugs and vaccines. This requires leveraging complementary in vitro assays—from DC activation and MAPPs to T-cell ELISpot—to build a robust risk profile before clinical trials [22]. The regulatory landscape demands careful control of product-related factors, especially impurities and aggregates, throughout the drug lifecycle [2]. As demonstrated by advanced peptide vaccine candidates, rational molecular design and precise analytical control can successfully minimize unwanted immunogenicity while achieving desired protective immunity. This structured, data-driven approach provides a reliable framework for researchers navigating the complex intersection of immunology, product quality, and regulatory science.

Core In Vitro Assays: From Epitope Screening to Functional Immune Readouts

The evaluation of cellular immunogenicity is a critical component in the development of peptide-based vaccines. Among the various techniques available, the Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) Enzyme-Linked Immunospot (ELISpot) assay has emerged as a cornerstone method for detecting and quantifying antigen-specific T-cell responses. This guide provides an objective comparison of the IFN-γ ELISpot assay with alternative methodologies, presenting experimental data and detailed protocols to inform assay selection in vaccine research and development. The focus is on practical implementation within the context of immunogenicity assessment for peptide-based vaccines, addressing the needs of researchers and drug development professionals seeking robust, sensitive, and reproducible immune monitoring tools.

Performance Comparison of T-Cell Activation Assays

Head-to-Head Assay Comparison

The selection of an appropriate T-cell activation assay depends on multiple factors, including the research question, sample availability, and required data granularity. The table below provides a comparative overview of three key technologies used in immunogenicity assessment.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Key T-Cell Immunogenicity Assays

| Parameter | IFN-γ ELISpot | Intracellular Cytokine Staining (ICS) | Cytokine Production (CP) ELISA |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is Measured | Frequency of cytokine-secreting cells [24] | Intracellular cytokines with cellular phenotype [25] | Total soluble cytokine concentration in supernatant [24] |

| Sample Type | Live PBMCs [24] | Live PBMCs [25] | Serum, plasma, or cell culture supernatant [24] |

| Sensitivity | Very high; detects rare responder cells [24] | Similar to ELISpot when optimized [25] | Moderate to high [24] |

| Key Output | Spot-forming units (SFU) per million cells [24] | Percentage or count of cytokine-positive T-cell subsets [25] | Cytokine concentration (e.g., pg/mL) [24] |

| Phenotypic Data | No | Yes (e.g., CD4/CD8, memory subsets) [25] | No |

| Multiplexing Capability | Single-plex (unless using Fluorospot) [25] | High (multiple cytokines and markers) [25] | Limited |

| Throughput | Moderate (cell handling can be a bottleneck) [24] | Moderate to High | High (easily automated) [24] |

| Specialized Equipment | ELISpot plate reader [24] | Flow cytometer [25] | Standard ELISA plate reader [24] |

Comparative Clinical Performance Data

Data from clinical studies directly comparing these assays demonstrate context-dependent performance. A 2025 study on tuberculosis diagnosis in a BCG-vaccinated Pakistani population found that an ELISPOT-based IGRA (X-DOT-TB) showed significantly higher sensitivity (79.5%, 95% CI: 77.4-81.5) for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection compared to an ELISA-based IGRA (QFT-Plus) at 55.7% (95% CI: 52.9-58.5) and the tuberculin skin test (TST) at 35.8% (95% CI: 34.4-37.1) [26]. The specificities were comparable at 85.1%, 78.1%, and 82.2%, respectively [26].

Similarly, a 2022 study comparing ELISpot and ICS for detecting SARS-CoV-2 T-cells in paucisymptomatic patients found that ELISpot identified a higher proportion of responders (67%) compared to ICS (44%), suggesting superior sensitivity for detecting low-frequency responses in certain contexts [27]. The magnitude of responses was also generally low, with a median of 61 Spot-Forming Cells (SFCs) per million PBMCs with ELISpot [27].

Table 2: Summary of Comparative Clinical Performance from Recent Studies

| Study Context | Compared Assays | Key Performance Finding | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tuberculosis diagnosis (Pakistani population) | ELISPOT-based IGRA vs. ELISA-based IGRA vs. TST | ELISPOT sensitivity: 79.5%ELISA IGRA sensitivity: 55.7%TST sensitivity: 35.8% [26] | Sci Rep. 2025 |

| SARS-CoV-2 T-cell detection (Paucisymptomatic patients) | ELISpot vs. ICS | Proportion of responders with ELISpot: 67%Proportion of responders with ICS: 44% [27] | Immunol Infect Dis. 2022 |

| HIV-specific T-cell responses | ELISpot vs. Cytokine Production (CP) ELISA | Both ELISpot and CP ELISA distinguished between patient groups; strong correlation between these two assays [28] | Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard IFN-γ ELISpot Protocol for Peptide-Based Vaccines

The following protocol is adapted from established methodologies used in vaccine immunogenicity studies [27] [29] [30].

Day 1: Plate Coating and Cell Preparation

- Coating: Add 100 μL/well of anti-IFN-γ capture antibody (e.g., 15 μg/mL in sterile PBS) to a PVDF-backed 96-well plate. Incubate overnight at 4°C.

- PBMC Thawing: Remove a cryovial of PBMCs from liquid nitrogen storage and thaw rapidly in a 37°C water bath.

- Washing: Transfer cells to a 15 mL tube pre-filled with warm R10 culture medium (RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS, L-glutamine, and antibiotics). Centrifuge at 400 × g for 10 minutes. Aspirate supernatant.

- Cell Counting: Resuspend cell pellet in 5-10 mL of R10 medium. Perform a viable cell count using Trypan Blue exclusion.

- Resting: Adjust cell concentration to 5-10 × 10^6 cells/mL and place the tube in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for at least 4 hours to allow cell recovery.

Day 2: Antigen Stimulation and Incubation

- Plate Blocking: Decant the coating antibody from the plate. Wash the plate 3 times with sterile PBS. Add 200 μL/well of R10 medium to block non-specific binding. Incurate for at least 2 hours at 37°C.

- Peptide Pools: Prepare the peptide pool(s) representing the vaccine antigens in R10 medium. Typical working concentration for individual 15-mer peptides overlapping by 11 amino acids is 1-2 μg/mL [27].

- Plate Setup:

- Test Wells: Add 100 μL of peptide solution per well in duplicate or triplicate.

- Positive Control Wells: Add 100 μL of a mitogen (e.g., PHA at 5 μg/mL).

- Negative Control Wells: Add 100 μL of R10 medium alone (with equivalent DMSO concentration if used for peptide solubilization).

- Cell Plating: Resuspend the rested PBMCs and plate at 100,000 to 250,000 cells per well in a volume of 100 μL [27] [24].

- Incubation: Incubate the plate for 16-24 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2. Do not move or disturb the plate during this time.

Day 3: Detection and Spot Development

- Cell Removal: Decant cell suspension and wash the plate 5 times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST).

- Detection Antibody: Add 100 μL/well of biotinylated anti-IFN-γ detection antibody (e.g., 1 μg/mL in PBST with 1% BSA). Incubate for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Enzyme Conjugate: Wash plate 5 times with PBST. Add 100 μL/well of Streptavidin-Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) conjugate, diluted per manufacturer's instructions. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Spot Development: Wash plate 5 times with PBST and then 2 times with PBS alone. Add 100 μL/well of precipitating substrate (e.g., AEC or TMB). Develop for 5-30 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Monitor spot formation.

- Stop Reaction: Once spots are distinct and background is low, stop the reaction by thoroughly washing the plate with tap water. Remove the plate underdrain and allow to air dry completely in the dark.

Day 3/4: Plate Reading and Analysis

- Reading: Count spots using an automated ELISpot plate reader.

- Analysis: Calculate the antigen-specific response for each sample:

Mean SFC (test) - Mean SFC (negative control) = Net SFC per well

(Net SFC per well / Number of cells plated per well) × 10^6 = SFC per million PBMCs

- Quality Control: The assay is valid if the negative control has low background (typically <10-20 spots) and the positive control shows a strong, expected response [27]. A response is typically considered positive if it is at least 2-fold above the negative control and exceeds a pre-defined threshold (e.g., 50 SFC/million PBMCs above background).

Protocol for Intracellular Cytokine Staining (ICS)

For comparative studies, ICS can be performed in parallel. This protocol is adapted from studies comparing ICS with ELISpot [27] [28].

- Stimulation: Stimulate 0.5-1 × 10^6 PBMCs per condition with the peptide pool (1 μg/mL) in the presence of a costimulatory antibody (e.g., anti-CD28/CD49d) and a protein transport inhibitor (e.g., Brefeldin A) for 4-18 hours at 37°C [27].

- Staining:

- Surface Staining: Wash cells and stain with surface marker antibodies (e.g., anti-CD3, CD4, CD8) for 20-30 minutes at 4°C.

- Fixation/Permeabilization: Wash cells, then fix and permeabilize them using a commercial cytofix/cytoperm solution.

- Intracellular Staining: Wash with perm/wash buffer and stain with antibodies against intracellular cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α) for 30 minutes at 4°C.

- Acquisition and Analysis: Wash cells and resuspend in fixation buffer. Acquire data on a flow cytometer. Analyze using flow cytometry software, gating on live, single lymphocytes, then on CD3+ T-cells, and further subdividing into CD4+ and CD8+ populations to identify the frequency of cytokine-positive cells within these subsets [27] [25].

Workflow and Decision-Making Diagrams

ELISpot Experimental Workflow

Assay Selection Decision Pathway

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the IFN-γ ELISpot assay requires high-quality, validated reagents. The following table details key materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for IFN-γ ELISpot

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the Assay | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-coated ELISpot Plates | Solid phase for capturing secreted cytokine; PVDF membranes are standard for high sensitivity. | Commercial kits (e.g., Mabtech, Oxford Immunotec, R&D Systems) ensure consistency and reliability [29]. |

| Peptide Pools / Antigens | Stimulate antigen-specific T-cells to secrete IFN-γ. | Overlapping peptide libraries (15-mers with 11-aa overlap) spanning vaccine antigens [27]. Use endotoxin-free peptides. |

| Cell Culture Medium | Maintain cell viability and support immune cell function during stimulation. | RPMI-1640 supplemented with fetal bovine serum (5-10%), L-glutamine, and antibiotics [27]. |

| Antibody Pairs | Capture and detect the cytokine of interest (IFN-γ). | Matched antibody pairs are critical for specificity and low background [24]. |

| Detection System | Amplify the signal for visualization of spots. | Typically involves a biotin-streptavidin-enzyme (HRP or AP) complex with a precipitating substrate [24]. |

| Positive Control Stimuli | Verify cell viability and functionality. | Mitogens like PHA or PMA/Ionomycin. Peptide pools from common pathogens (e.g., CEF pool) can also be used [27]. |

| Cryopreserved PBMCs | Starting material for the assay; allows batch testing. | High-quality PBMCs with high post-thaw viability are essential. Use controlled-rate freezing and proper cryoprotectant (e.g., DMSO/FCS) [31]. |

The IFN-γ ELISpot assay remains a powerful, highly sensitive tool for quantifying antigen-specific T-cell responses in peptide-based vaccine development. Its primary advantage lies in its exceptional sensitivity for detecting low-frequency T-cell responses, making it ideal for screening immunogenicity. However, the choice between ELISpot, ICS, and other immunoassays is not a matter of which is universally superior, but which is most appropriate for the specific research objective. ICS provides unparalleled detail on T-cell phenotype and polyfunctionality, while ELISA offers a high-throughput method for quantifying total cytokine secretion. A strategic approach often involves using ELISpot for initial screening and ICS for in-depth characterization of positive responses, thereby leveraging the strengths of both assays to build a comprehensive understanding of vaccine-induced cellular immunity.

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) stands as a cornerstone technique for assessing humoral immune responses, particularly in the development of peptide-based vaccines. This immunological biochemical assay detects antigen-antibody interactions using enzyme-labelled conjugates and substrates that generate measurable color changes, providing critical data on vaccine immunogenicity [32]. In vaccine development, ELISA enables researchers to quantify antigen-specific antibody titers, establishing correlates of protection and bridging immunological results across different vaccine platforms and clinical trials [33]. The technique's high throughput, quantitative capabilities, and specificity make it indispensable for evaluating vaccine-induced immune responses, monitoring antibody persistence, and facilitating vaccine licensure [34] [33].

For peptide-based vaccines, which often consist of synthetic immunogenic epitopes, ELISA provides a direct method to measure the magnitude and quality of the antibody response against target antigens. As demonstrated in Shigella vaccine studies, measurement of serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) to pathogen-specific antigens has been proposed as a key correlate of protection against infection [33]. Similarly, in cancer vaccine development, including multi-epitope peptide vaccines targeting triple-negative breast cancer, ELISA methodologies enable researchers to verify that designed constructs elicit robust antibody responses against selected tumor-associated antigens [35] [36]. The ability to precisely quantify these humoral responses is essential for selecting the most promising vaccine candidates for further development.

ELISA Methodologies: A Comparative Analysis

Core ELISA Formats and Applications

Different ELISA formats offer distinct advantages for specific applications in vaccine immunogenicity assessment. Understanding these methodologies is crucial for selecting the appropriate approach for evaluating antigen-specific antibody titers.

Table 1: Comparison of Major ELISA Formats for Antibody Detection

| Format | Principle | Sensitivity | Specificity | Best Applications in Vaccine Studies | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct ELISA | Antigen coated on plate; detected with enzyme-labeled primary antibody | Low | Moderate | High-throughput screening of purified antibodies; epitope mapping | Requires labeled primary antibodies for each target; lower sensitivity |

| Indirect ELISA | Antigen coated on plate; detected with unlabeled primary and enzyme-labeled secondary antibodies | High | Moderate | Measuring antibody titers in immunized sera; vaccine response monitoring | Potential cross-reactivity with secondary antibodies |

| Sandwich ELISA | Capture antibody coated on plate; antigen "sandwiched" between capture and detection antibodies | Highest | Highest | Complex samples; low abundance antigens; precise quantification of specific antibodies | Requires matched antibody pairs; more complex optimization |

| Competitive/Inhibition ELISA | Sample antibodies compete with labeled reference for antigen binding | Variable | High | Measuring antibodies against small molecules; analyzing antibody affinity | Inverse signal relationship; complex data interpretation |

The indirect ELISA format is particularly valuable in vaccine studies for measuring antibody titers in immunized subjects, as it offers high sensitivity and flexibility without requiring labeled primary antibodies [34]. The signal amplification achieved through multiple secondary antibodies binding to a single primary antibody makes this format ideal for detecting lower antibody concentrations often encountered in early vaccine development. For peptide-based vaccines, where targets are well-defined and purity is high, indirect ELISA provides reliable quantification of antigen-specific responses.

The sandwich ELISA format offers superior specificity for complex sample matrices, as two antibodies are required to recognize the target antigen simultaneously [34]. This format is especially useful when analyzing serum samples with potential cross-reactive antibodies or when measuring specific antibody isotypes in polyclonal responses. However, this approach requires carefully optimized antibody pairs that recognize non-overlapping epitopes, which can be challenging for small peptide antigens.

Competitive ELISA formats are particularly valuable for assessing antibody responses against small epitopes or when evaluating antibody affinity maturation following vaccination [34] [37]. The inverse relationship between signal and analyte concentration (higher antibody titer produces lower signal) provides a robust method for quantifying antibodies in complex biological fluids without requiring extensive sample purification.

Experimental Protocol: Indirect ELISA for Vaccine Antibody Assessment

The following detailed protocol outlines the standard procedure for quantifying antigen-specific antibody titers using indirect ELISA, adapted from established methodologies in vaccine research [34] [32]:

Plate Coating: Dilute purified antigen (e.g., vaccine peptide or target protein) in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) to a concentration of 1-10 μg/mL. Add 100 μL/well to a 96-well polystyrene microplate and incubate overnight at 4°C. The optimal coating concentration should be determined empirically for each antigen.

Washing: Discard the coating solution and wash the plate three times with PBS-Tween 20 (0.05%) using an automated plate washer or manual washing system. Each wash should consist of filling wells completely, soaking for 30-60 seconds, and thoroughly decanting the solution.

Blocking: Add 200-300 μL/well of blocking buffer (1-5% BSA or non-fat dry milk in PBS) to cover all potential binding sites. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Wash plate three times as before.

Primary Antibody Incubation: Prepare serial dilutions of test sera (from vaccinated subjects) and controls in sample diluent (blocking buffer with 0.05% Tween-20). Include negative control sera (pre-immune or from unvaccinated subjects) and positive control sera when available. Add 100 μL/well of each dilution in duplicate or triplicate. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature or 37°C. Wash plate three times.

Secondary Antibody Incubation: Dilute enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., HRP-anti-species IgG) in sample diluent according to manufacturer's recommendations. Add 100 μL/well and incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Wash plate three times.

Signal Detection: Prepare enzyme substrate solution immediately before use (e.g., TMB for HRP). Add 100 μL/well and incubate in the dark for 15-30 minutes, monitoring color development.

Reaction Stopping: Add 50-100 μL/well of stop solution (e.g., 1M H₂SO₄ for TMB). The solution color will change from blue to yellow when using acid stop solutions with TMB.

Absorbance Measurement: Read optical density (OD) at appropriate wavelength (e.g., 450nm for TMB) using a microplate spectrophotometer within 30 minutes of stopping the reaction.

For quantitative assessment, include a standard curve with known concentrations of the target antibody whenever possible. When absolute quantification is not feasible, report results as endpoint titers, defined as the highest serum dilution that produces an OD value significantly above the negative control (typically 2-3 standard deviations above the mean negative control value) [33] [38].

Quantitative Data Analysis and Standardization

Standard Curve Generation and Data Interpretation

Accurate quantification of antibody titers relies on proper standard curve implementation and data analysis techniques. The following workflow ensures reliable results:

Standard Preparation: Prepare a series of 2-fold or 3-fold dilutions from a high-concentration standard, ensuring the range covers expected sample values. Include at least 6-8 standard points plus a zero standard (blank) [38].

Background Subtraction: Subtract the OD of the blank well (zero standard) from all other readings to eliminate background signal: Adjusted OD = Sample OD - Blank OD [38].

Curve Fitting: Use appropriate curve-fitting models for the standard curve. The 4-parameter logistic (4PL) model is recommended for most ELISA applications due to its flexibility and sigmoidal fit [38] [39]. The 4PL equation is: Y = D + (A - D) / (1 + (X / C)á´®), where A = minimum asymptote, D = maximum asymptote, C = inflection point (ECâ‚…â‚€), and B = slope factor.

Sample Concentration Interpolation: Use the fitted standard curve to interpolate concentrations of unknown samples from their adjusted OD values. Ensure sample ODs fall within the standard curve range. If not, dilute samples further and re-test [38].

Dilution Factor Correction: Multiply interpolated values by the dilution factor to obtain original concentrations: Final concentration = Interpolated value × Dilution factor [38].

For qualitative or semi-quantitative analysis, establish a cutoff value using statistical approaches: Cutoff = Mean OD of negative controls + 2 × Standard Deviation (SD). Samples with OD values above this cutoff are considered positive [38].

Inter-laboratory Standardization and Bridging Studies

Standardization of ELISA methodologies across different laboratories is essential for meaningful comparison of immunogenicity data from various vaccine trials. As highlighted in Shigella vaccine research, lack of standardization means that antibody measurements from different studies cannot be easily compared [33]. Bridging studies using shared serum panels enable conversion of results between different ELISA methods.

Table 2: Cross-Comparison of ELISA Methodologies from Shigella Vaccine Studies

| Laboratory/Method | Reported Units | Correlation with Reference Method | *Corresponding Titer to Protective Threshold | Application in Vaccine Trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tel Aviv University (TAU) ELISA | Endpoint titer | Reference method | 1,600 (established protective threshold) | Original efficacy trials |

| GVGH ELISA | ELISA Units (EU/mL) vs. internal reference | Excellent correlation | Calculated equivalent value | GMMA-based vaccine trials |

| Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) ELISA | Endpoint titer | Excellent correlation | Calculated equivalent value | Multiple vaccine candidates |

*Protective threshold established as ≥1,600 anti-S. sonnei LPS IgG at day 17 post-vaccination, associated with 73.6% vaccine efficacy [33].

The excellent correlation observed between different ELISA methodologies in Shigella research demonstrates that properly standardized assays can generate comparable data, facilitating vaccine development and licensure [33]. Such bridging studies are particularly valuable when international standard sera are not yet available, allowing immunological bridging to other populations, vaccine formulations, or platforms.

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ELISA-Based Humoral Immunity Assessment

| Reagent/Category | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Phase | Provides surface for antigen or antibody immobilization | 96-well polystyrene plates; high protein-binding capacity; uniform well dimensions |

| Coating Antigens | Target for antibody detection in sample | Peptide purity >90%; correct folding/conformation; lyophilized for stability |

| Detection Antibodies | Enzyme-conjugated antibodies for signal generation | Species specificity; minimal cross-reactivity; HRP or AP conjugation |

| Reference Standards | Quantitative calibration of assay | International standards if available; in-house reference sera characterized for stability |

| Enzyme Substrates | Chromogenic or chemiluminescent signal generation | TMB (colorimetric) for HRP; pNPP for AP; sensitivity and dynamic range |

| Blocking Buffers | Prevent non-specific binding | BSA, non-fat milk, or commercial protein blockers; compatibility with antigens |

| Sample Diluents | Matrix for serum/plasma samples | Maintain antibody stability; minimize background; protein-based with preservatives |

| Plate Washers | Remove unbound materials | Consistent washing pressure; complete well coverage; minimal cross-contamination |

| Microplate Readers | Absorbance measurement | Accurate wavelength selection; sensitivity across dynamic range; data export capabilities |

Visualization of ELISA Workflow and Data Analysis

ELISA Experimental Workflow

ELISA Data Analysis Process

ELISA methodologies provide robust, quantitative tools for assessing antigen-specific antibody titers in peptide-based vaccine development. The selection of appropriate formats—whether indirect, sandwich, or competitive ELISA—depends on the specific vaccine antigens, available reagents, and required sensitivity. Standardization through bridging studies and implementation of rigorous data analysis protocols, including 4-parameter logistic curve fitting, enables reliable comparison of immunogenicity data across vaccine candidates and clinical trials. As vaccine technologies evolve, particularly in the realm of synthetic peptide vaccines, ELISA remains an essential component in the immunogenicity assessment toolkit, providing critical data to establish correlates of protection and guide vaccine development decisions.