Antibody Validation for Flow Cytometry and Western Blot: A Guide to Reproducible Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating antibodies for flow cytometry and western blot applications.

Antibody Validation for Flow Cytometry and Western Blot: A Guide to Reproducible Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating antibodies for flow cytometry and western blot applications. It addresses the critical need for rigorous antibody validation, a key factor in the biomedical research reproducibility crisis, where studies suggest over 50% of commercial antibodies may fail in specific applications. The content covers foundational principles, standardized methodological protocols for both techniques, practical troubleshooting advice, and a comparative analysis to guide method selection. By synthesizing current validation frameworks, market trends, and optimization strategies, this resource aims to empower scientists to generate reliable, high-quality data, thereby enhancing research efficiency and therapeutic development.

The Critical Role of Antibody Validation in Modern Biomedical Research

Antibodies are fundamental tools in biomedical and clinical research, enabling scientists to detect, quantify, and localize specific proteins within complex biological systems. However, a pervasive crisis threatens the validity of countless studies: the antibody reproducibility problem. With over six million commercially available antibodies today—a dramatic increase from approximately 10,000 just 15 years ago—the research community faces significant challenges in quality control and characterization [1]. Estimates indicate that roughly 50% of commercial antibodies fail to meet even basic characterization standards, resulting in financial losses of $0.4–1.8 billion annually in the United States alone [1]. This crisis stems from inadequate antibody characterization coupled with insufficient user training, leading to a proliferation of scientific publications containing misleading or incorrect interpretations based on unreliable antibody data [1].

The Scale of the Problem: Quantifying the Antibody Crisis

Root Causes and Contributing Factors

The antibody reproducibility crisis has multifaceted origins that have evolved over decades. The early 2000s marked a critical turning point with the availability of the first near-complete human genome sequence, which shifted research focus toward proteomic studies and dramatically increased demand for protein detection reagents [1]. This surge prompted rapid commercial expansion without parallel development of standardized validation protocols.

A fundamental economic driver of this crisis lies in the disconnect between characterization costs and market realities. The expenses associated with proper antibody characterization—including Western blotting, immunoprecipitation, immunofluorescence, and knockout validation—far exceed the revenues generated from the average antibody on the market today [1]. This economic reality has shifted the burden of characterization onto end-users, who often lack the resources or expertise to perform adequate validation.

Impact on Research and Drug Development

The consequences of poorly characterized antibodies ripple across the research landscape. Clinical trials have been compromised by unreliable antibodies, with stark examples including patient trials based on incorrect antibody data [1]. Beyond financial costs, the crisis damages scientific careers, affects mental health, and erodes trust in the scientific literature [2].

The problem is particularly acute for polyclonal antibodies, whose non-renewable nature and complex composition introduce significant batch-to-batch variability [1]. This variability manifests as false positives, increased background noise, and inconsistent performance across experiments, fundamentally undermining research reproducibility.

Comparative Analysis of Antibody Performance Across Applications

Application-Specific Performance Variations

Antibody performance varies significantly across different experimental applications, making context-specific characterization essential. The same antibody may perform reliably in one application while failing completely in another due to differences in sample preparation, epitope presentation, and detection methods.

Table 1: Antibody Performance Across Common Research Applications

| Application | Key Strengths | Critical Validation Parameters | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western Blot | Confirms target protein size; detects isoforms and post-translational modifications [3] | Specific band at expected molecular weight; knockout validation [4] | Non-specific bands; incomplete denaturation; epitope destruction [5] |

| Flow Cytometry | Single-cell resolution; multi-parametric analysis; native conformation detection [3] | Specific staining in known positive cells; isotype controls; compensation controls [4] | Non-specific binding; improper fixation; fluorophore interference [3] |

| Immunofluorescence | Subcellular localization; co-localization studies [4] | Appropriate subcellular pattern; knockout validation; fixation compatibility [4] | Autofluorescence; antibody cross-reactivity; improper permeabilization [1] |

| Immunohistochemistry | Tissue context; disease biomarker validation [4] | Staining in known positive tissues; tissue microarray validation [4] | Background staining; antigen retrieval issues; batch variability [1] |

| ELISA | Quantification; high throughput; clinical applications [3] | Spike-recovery (80-120%); linear dilution; <5% cross-reactivity [4] | Matrix effects; hook effect; non-specific binding [3] |

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

Different antibody-based techniques offer distinct advantages and limitations, making each suitable for specific research questions. Understanding these differences is crucial for appropriate experimental design and interpretation.

Table 2: Technical Comparison of Major Antibody-Based Assays

| Parameter | Western Blot | Flow Cytometry | ELISA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity & Specificity | High specificity for size detection; may miss conformational epitopes [3] | Very high sensitivity (single-cell level); high specificity with proper gating [3] | High sensitivity (pg–ng/mL range); excellent for soluble proteins [3] |

| Sample Type & Throughput | Lysates from tissue or cells; low to moderate throughput [3] | Live or fixed cell suspensions; moderate to high throughput (10,000+ cells/sec) [3] | Serum, plasma, cell culture supernatants; high throughput (96–384 well plates) [3] |

| Cost & Time Efficiency | Labor-intensive (1–2 days); moderate reagent costs [3] | Higher instrument cost; complex setup; minutes to hours for analysis [3] | Cost-effective; results in 2–6 hours; amenable to automation [3] |

| Key Applications | Protein expression validation; molecular weight confirmation; PTM detection [5] [3] | Cell population analysis; immunophenotyping; intracellular signaling [3] | Biomarker quantification; antibody titer determination; diagnostic applications [4] [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Antibody Validation

Western Blot Validation Standards

Proper Western blot validation requires rigorous controls and optimized conditions to ensure specific detection of the target protein. Sample preparation begins with cell lysis using appropriate buffers (e.g., RIPA buffer for whole cell extracts) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors to prevent protein degradation [5]. Following protein concentration determination via BCA or Bradford assay, samples are diluted in Laemmli buffer containing reducing agents (DTT or β-mercaptoethanol) and heated to denature proteins [5].

Critical validation steps include:

- Knockout Controls: Using CRISPR/Cas9-generated knockout cell lines to confirm absence of signal [4]

- Positive Controls: Lysates from cells or tissues with known target expression [4]

- Loading Controls: Housekeeping proteins (e.g., α-tubulin, GAPDH) to normalize protein loading [4]

- Molecular Weight Verification: Confirmation that detected bands align with expected protein size [4]

For low-abundance proteins, enrichment strategies such as immunoprecipitation or wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) bead purification may be necessary prior to Western blot analysis [5].

Flow Cytometry Validation Framework

Comprehensive flow cytometry validation ensures accurate detection of cell surface and intracellular markers. The protocol begins with sample preparation, using live cells for surface markers or fixed and permeabilized cells for intracellular targets. Key validation components include:

- Specificity Controls: Comparison of staining in known positive and negative cell populations [3]

- Isotype Controls: Matching immunoglobulin isotypes to assess non-specific binding [3]

- Titration Optimization: Determination of optimal antibody concentration through serial dilution [4]

- Fluorescence Compensation: Use of compensation beads to correct for spectral overlap [3]

- Viability Staining: Exclusion of dead cells that may exhibit non-specific antibody binding [3]

Advanced validation may include genetic approaches (knockout cells) or orthogonal methods to confirm target identity [4].

Orthogonal Validation Approaches

The International Working Group for Antibody Validation (IWGAV) recommends multiple complementary strategies to confirm antibody specificity:

- Genetic Strategies: Using knockout cells or tissues to demonstrate signal loss [2] [4]

- Orthogonal Methods: Comparing antibody-based detection with independent methods (e.g., RNA sequencing, mass spectrometry) [2]

- Independent Antibodies: Confirming results with multiple antibodies targeting different epitopes of the same protein [2]

- Expression Patterns: Verifying that detection patterns match known tissue or subcellular distribution [2]

- Biophysical Characterization: Assessing antibody purity, aggregation, and identity through mass spectrometry and chromatography [6]

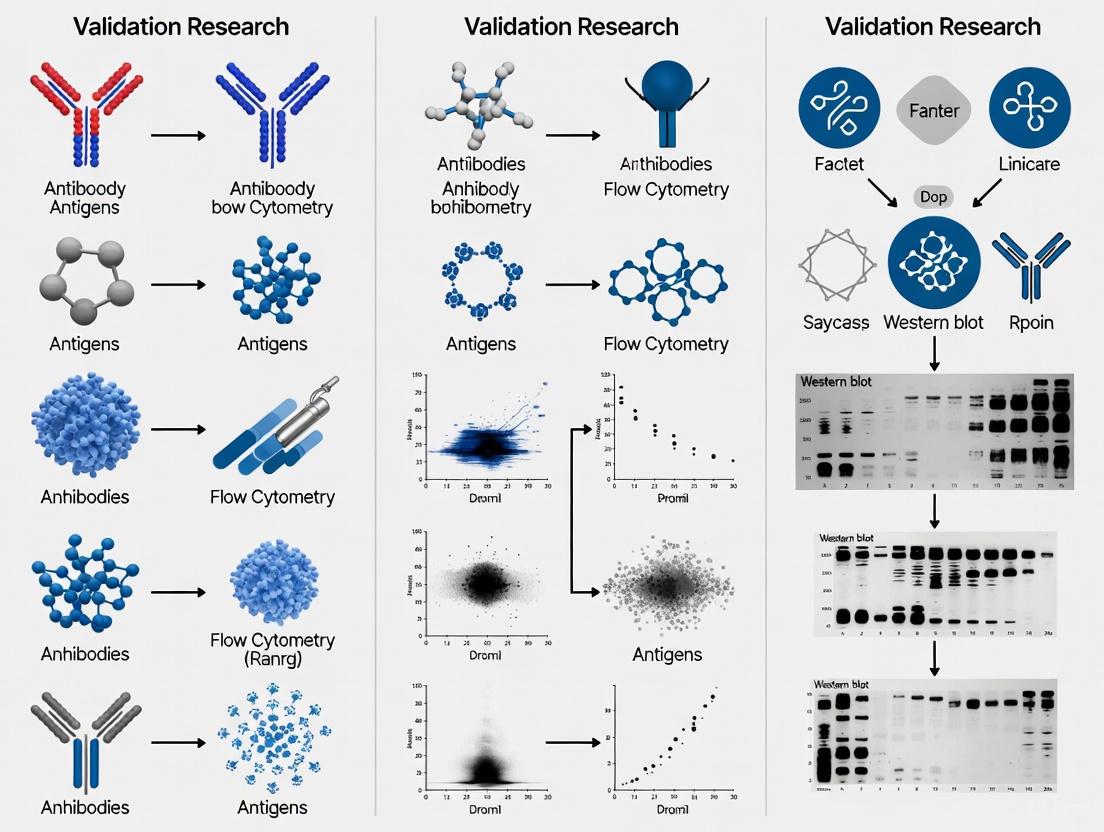

Standardized Workflows for Antibody Characterization

The antibody validation process requires a systematic approach to ensure reliable performance across applications. The following workflow diagrams illustrate standardized pathways for comprehensive antibody characterization.

Antibody Validation Workflow: This systematic approach ensures comprehensive characterization before experimental use.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Critical Reagents for Antibody Applications

Successful antibody-based research requires carefully selected reagents and controls. The following toolkit outlines essential components for reliable experimentation:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Antibody Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF (1 mM), Aprotinin (2 µg/ml), Leupeptin (1-10 µg/ml) [5] | Prevent protein degradation during sample preparation; essential for preserving target integrity [5] |

| Phosphatase Inhibitors | Sodium orthovanadate (1 mM), Sodium fluoride (5-10 mM), β-glycerophosphate (1-2 mM) [5] | Maintain phosphorylation states; critical for signaling studies and phospho-specific antibodies [5] |

| Lysis Buffers | RIPA buffer, NP-40 buffer, Tris-HCl, Tris-Triton [5] | Extract proteins based on subcellular localization; choice depends on target protein and application [5] |

| Blocking Agents | BSA, normal serum, non-fat dry milk, casein [5] | Reduce non-specific binding; optimal agent varies by application and detection method [5] |

| Detection Systems | HRP-conjugated secondaries, fluorescent dyes, ECL substrates [5] [4] | Enable signal generation; selection depends on required sensitivity and instrumentation [5] |

| Validation Tools | Knockout cell lines, isotype controls, peptide antigens [4] [6] | Confirm antibody specificity; essential for verifying target engagement [4] |

Selection Framework for Antibody and Application Matching

Choosing the appropriate antibody and application pair requires careful consideration of multiple factors. The following decision pathway illustrates a systematic approach to method selection.

Antibody Application Selection Guide: This decision pathway helps researchers match their research questions with appropriate detection methods.

Solutions and Future Directions

Industry Initiatives and Quality Improvements

The research community and leading antibody manufacturers have implemented various strategies to address the reproducibility crisis. Recombinant antibody technology represents a significant advancement, providing renewable resources with minimal batch-to-batch variability [6]. Companies like Abcam have introduced biophysical "fingerprinting" using techniques including liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and dynamic light scattering to confirm antibody identity, purity, and aggregation states [6].

Cell Signaling Technology has developed comprehensive validation standards called the "Hallmarks of Antibody Validation" incorporating six complementary strategies: genetic strategies, orthogonal methods, independent antibody correlation, range expression, heterologous expression, and domain-specific validation [2]. These approaches align with IWGAV recommendations while exceeding basic requirements through more rigorous testing.

Initiatives such as the Antibody Registry and Research Resource Identification Initiative have improved antibody identifiability in scientific publications [6]. However, studies indicate that authors still fail to identify antibodies used in their research in 20-50% of publications [6]. Enhanced reporting standards requiring detailed antibody characterization (including catalog numbers, lot numbers, and validation data) are essential for improving reproducibility.

Public characterization efforts like YCharOS (an open science platform for antibody validation) provide independent assessment of antibody performance against specific human targets [7]. These community resources help researchers select appropriate reagents while encouraging manufacturers to maintain high validation standards.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

Addressing the antibody reproducibility crisis requires coordinated action across multiple stakeholders:

- Researchers: Perform application-specific validation; include appropriate controls; report antibody identifiers and characterization data [1]

- Universities: Incorporate antibody validation training into graduate programs; establish core facilities for validation support [1]

- Journals: Enforce strict antibody reporting standards; require experimental validation data [1]

- Vendors: Provide comprehensive characterization data; implement recombinant technologies; ensure batch-to-batch consistency [1] [6]

- Funders: Support antibody validation initiatives; require data sharing; fund development of well-characterized reagents [1]

The antibody reproducibility crisis represents a fundamental challenge to biomedical research validity, with approximately half of commercial antibodies failing basic characterization standards and contributing to billions of dollars in wasted research funding. Solving this crisis requires recognizing that antibody characterization is not a one-time event but an ongoing, application-specific process. Through implementation of rigorous validation standards, adoption of recombinant technologies, enhanced reporting practices, and stakeholder collaboration, the research community can transform antibodies from sources of irreproducibility into reliable tools for scientific discovery. The path forward demands shared responsibility, with manufacturers providing better characterization data and researchers committing to thorough validation and transparent reporting—only through this collaborative approach can we restore confidence in antibody-based research.

The global antibodies market is experiencing a period of exceptional growth, fundamentally reshaping the biomedical and therapeutic landscapes. This expansion is primarily fueled by relentless innovation, particularly the advent of sophisticated engineered formats like bispecific antibodies, which are creating new treatment paradigms for complex diseases such as cancer. The market, valued in the hundreds of billions of dollars, is supported by rising R&D expenditures, strategic industry collaborations, and a growing emphasis on precision medicine. However, this growth is tempered by significant challenges, including high production costs, complex manufacturing requirements, and stringent regulatory hurdles. This analysis delves into the quantitative market data, core growth drivers, and the tangible economic impact of these dynamic forces, providing a structured comparison for researchers and drug development professionals.

The antibodies market represents a substantial and rapidly expanding segment of the global biopharmaceutical industry. The broader market, encompassing various antibody types, is on a strong upward trajectory, with the more specialized bispecific antibodies segment exhibiting particularly explosive growth.

Table 1: Global Antibodies Market Size and Projections

| Market Segment | Base Year Value (2024/2025) | Projected Value | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | Time Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Antibodies Market [8] | USD 272.6 Billion (2024) | USD 886.4 Billion | 14.0% | 2024-2033 |

| Bispecific Antibodies Market [9] [10] | USD 9.98 Billion (2025) | USD 76.67 Billion | 33.72% | 2025-2032 |

| Bispecific Antibodies Market [11] | USD 5.6 Billion (2025) | USD 16.8 Billion | 9.5% | 2025-2035 |

| Antibody Discovery Market [12] | USD 8.95 Billion (2025) | USD 20.43 Billion | 9.54% | 2025-2034 |

The data reveals a consistent narrative of robust growth across all segments. The remarkable CAGR of the bispecific antibodies market, as highlighted in multiple reports, underscores its role as a primary innovation and value driver within the broader field [9] [10]. This growth is largely attributed to a flourishing pipeline; over 400 clinical and preclinical bispecific candidates are currently being evaluated by more than 120 drug developers worldwide [11].

Key Market Drivers and Industry Trends

The expansion of the antibodies market is not serendipitous but is propelled by a confluence of powerful technological, clinical, and strategic factors.

- Technological Advancements in Engineering: Progress in antibody engineering platforms—such as CrossMab, DuoBody, and knobs-into-holes technologies—is facilitating the streamlined production and commercialization of bispecific antibodies [9] [10]. Furthermore, the integration of AI-driven in silico modeling is optimizing binding affinity and manufacturability, accelerating the discovery timeline [9] [13].

- Rising Demand for Targeted Therapies: There is a growing clinical and commercial demand for treatments that offer greater efficacy with fewer side effects. Bispecific antibodies meet this need by enabling novel mechanisms of action, such as redirecting T-cells to tumor cells (e.g., T-cell engagers like BiTEs and DARTs) and dual checkpoint inhibition [9] [10]. This is particularly impactful in oncology, the dominant therapeutic area, but is also expanding into autoimmune and infectious diseases [9].

- Strategic Collaborations and Partnerships: The industry is witnessing a surge in partnerships between large pharmaceutical companies and specialized biotechnology firms. These collaborations are crucial for accelerating bispecific antibody development pipelines, combining the R&D agility of biotechs with the commercial scale and resources of big pharma [9] [11].

- Expansion in Precision Medicine: The push for personalized medicine is creating demand for highly specific research reagents and therapeutic antibodies capable of discriminating between closely related protein isoforms and novel epitopes identified through multi-omics integration [13] [14].

Economic Impact and Industry Challenges

The burgeoning antibodies market exerts a profound economic impact across the healthcare ecosystem, while also presenting distinct challenges that must be navigated.

Table 2: Analysis of Economic Impact and Key Challenges

| Aspect | Economic Impact / Challenge Description | Supporting Data / Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| R&D Investment | Significant capital inflow from major pharmaceutical companies, fueling further innovation. | AbbVie raised R&D spending by 60% to USD 12.8 billion in 2024 [14]. |

| Therapeutic Pricing | High development and production costs influence the final price of antibody therapeutics. | Treatment courses for monoclonal antibodies can cost between USD 15,624 and USD 143,833 [14]. |

| Supply Chain Dynamics | Global logistics and potential trade policies directly affect operational costs and planning. | Anticipated 2025 U.S. tariff changes are prompting a reconfiguration of global biologics supply networks [9] [10]. |

| Production Challenges | High costs and complex processes can hinder development and market access. | Generating antibodies against difficult targets can push budgets above USD 500,000 [13]. |

| Validation & Reproducibility | Batch-to-batch variability in research antibodies can lead to experimental failure and wasted resources. | One study found two-thirds of tested antibodies underperformed against manufacturer claims [14]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers validating antibodies for applications like flow cytometry and Western blot, understanding the key reagents and their functions is critical for experimental success.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Antibody Validation

| Reagent / Material | Core Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibodies [14] | Identical antibodies targeting a single, specific epitope; essential for consistent, high-specificity assays. | Dominant in ELISA, Western blot, and flow cytometry; provides high specificity but can have batch variability. |

| Recombinant Antibodies [13] [14] | Engineered antibodies produced from known DNA sequences; offer superior lot-to-lot consistency and defined specificity. | Growing adoption (10.23% CAGR) due to reproducibility; ideal for critical validation work and multiplexed imaging [14]. |

| Secondary Antibodies [14] | Bind to the constant region of primary antibodies, enabling detection through conjugation to enzymes or fluorophores. | Critical for signal amplification; growth driven by multiplex fluorescence and high-content screening. |

| Validated Controls & Isotypes [14] | Essential for verifying assay specificity, ruling out non-specific binding, and ensuring accurate data interpretation. | Use is rising as journals and funders tighten reproducibility requirements. |

| Phage/Yeast Display Libraries [12] [13] | In vitro platforms for discovering and engineering high-affinity antibodies against a vast array of targets. | Phage display is a leading method; automated platforms are accelerating discovery timelines [12]. |

Experimental Workflow for Antibody Validation

A rigorous, multi-step validation protocol is indispensable for confirming antibody specificity and functionality, especially before use in critical applications. The workflow below outlines a standard methodology for validating a research antibody for flow cytometry and Western blot.

Antibody Validation Workflow

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Steps:

Protocol 1: Specificity Validation via Western Blot using Knockout Controls

- Methodology: Parallel Western blot analysis is performed on lysates from wild-type (WT) cells and genetically engineered knockout (KO) cells lacking the target protein.

- Procedure:

- Prepare protein lysates from WT and KO cell lines.

- Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a membrane.

- Incubate the membrane with the antibody under validation.

- Develop the blot and analyze the signal. A specific antibody will produce a band at the expected molecular weight in the WT lane and show a clear absence of that band in the KO lane.

- Data Interpretation: The disappearance of the band in the KO lane confirms antibody specificity. Persistent bands in the KO lane indicate non-specific binding [14].

Protocol 2: Functional Validation for Flow Cytometry via Antigen Overexpression

- Methodology: The antibody's ability to detect cell surface antigens is tested using a cell line engineered to overexpress the target protein, compared to a control cell line with low or no expression.

- Procedure:

- Harvest and stain control (negative) and antigen-overexpressing (positive) cells with the antibody.

- Include an isotype control antibody to account for non-specific Fc receptor binding.

- Analyze the cells using a flow cytometer.

- The positive cells should show a significant rightward shift in fluorescence intensity compared to the control cells and the isotype control.

- Data Interpretation: A clear, distinct fluorescence shift in the positive population confirms the antibody's specificity and functionality for flow cytometry applications.

Regional Dynamics and Competitive Landscape

The global antibodies market is characterized by distinct regional dominance and growth patterns, alongside a competitive ecosystem of established leaders and innovative specialists.

Regional Analysis: North America consistently holds the leading market share (e.g., 44.7% of the overall antibodies market in 2023 [8] and 40.25% of the custom antibody market in 2024 [13]), supported by robust biopharmaceutical infrastructure, high R&D spending, and favorable regulatory policies. However, the Asia-Pacific region is projected to be the fastest-growing market, driven by expanding healthcare infrastructure, rising pharmaceutical investments, and increasing clinical trial activity, particularly in China and South Korea [8] [14].

Key Industry Players: The market features a mix of long-established pharmaceutical giants and specialized biotechnology firms. Key players profiled across the search results include F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Amgen Inc., Janssen Biotech, Pfizer Inc., AbbVie Inc., Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca PLC, Merck & Co., and Genmab A/S [9] [11] [10]. The competitive landscape is further enriched by technology-focused companies and CROs such as Thermo Fisher Scientific, which strengthens its capabilities through strategic acquisitions like Olink [14].

The market for antibodies, particularly innovative formats like bispecifics, is in a phase of unprecedented growth and transformation. Driven by technological breakthroughs, strategic collaborations, and a relentless pursuit of more effective therapies, this sector presents immense opportunity for researchers and drug developers. However, to fully capitalize on this potential, the industry must continue to address the persistent challenges of cost, manufacturing complexity, and—most critically for the research community—the imperative for rigorous antibody validation to ensure experimental reproducibility and scientific progress.

In the fields of biomedical research and drug development, the reliability of experimental data is paramount. Specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility form the foundational triad of antibody validation, ensuring that research findings are accurate, meaningful, and verifiable. Specificity confirms an antibody binds exclusively to its intended target, sensitivity defines its detection limit for the target, and reproducibility guarantees consistent performance across experiments and batches. For researchers and scientists, rigorous assessment of these principles is critical, as poorly characterized reagents remain a significant source of irreproducible results, wasting valuable time and resources. This guide explores these core principles through the specific lenses of flow cytometry and Western blotting, providing structured data, experimental protocols, and visual workflows to support robust antibody validation.

Core Principles of Antibody Validation

Specificity

Specificity refers to an antibody's ability to bind exclusively to its target protein and not to other, non-target components in a sample. A highly specific antibody minimizes off-target binding and cross-reactivity, which is crucial for the accurate interpretation of experimental results.

- Validation Methods: Key strategies for confirming specificity include the use of genetic controls such as knockout (KO) or knockdown (KD) cell lines, where the target gene has been deactivated. In these cells, a specific antibody should show no signal [15] [16]. Orthogonal validation uses an antibody-independent method to quantify the target and compare it with antibody-based results [15] [16]. The independent antibody strategy involves using two or more antibodies recognizing different epitopes on the same target to confirm the observed signal [15] [16].

Sensitivity

Sensitivity is the lowest concentration of a target antigen that an antibody can reliably detect. It determines the threshold for detection in an assay and is vital for identifying low-abundance proteins.

- Quantification: Sensitivity is often quantified by determining the limit of detection (LOD) in a given assay. For instance, ELISA can detect targets in the picogram to nanogram per milliliter range, while flow cytometry can achieve sensitivity at the single-cell level [3].

- Impact of Validation: Properly validating sensitivity ensures that an antibody is fit for its intended application, preventing false negatives and enabling the study of proteins expressed at low levels.

Reproducibility

Reproducibility ensures that an antibody delivers consistent results when used in the same assay by the same or different researchers, across multiple experiments, and, critically, across different production lots.

- Standardization for Consistency: A major challenge in the antibody industry is batch-to-batch variation. Reproducibility is enhanced through rigorous validation under application-specific conditions and detailed documentation of protocols and results [17] [18]. Community-driven initiatives, such as the EV Antibody Database, aim to improve reproducibility by aggregating and sharing validation data from multiple laboratories [17].

Application in Key Techniques: Flow Cytometry vs. Western Blot

The principles of specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility are applied differently depending on the assay platform. The table below summarizes their performance and key differentiators.

| Parameter | Flow Cytometry | Western Blot |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | High specificity with proper gating and controls; dependent on native protein conformation [3]. | High specificity for detecting size-specific isoforms and post-translational modifications; dependent on linear epitopes [3]. |

| Sensitivity | Very high sensitivity (single-cell level) [3]. | High sensitivity, capable of detecting low-abundance proteins with optimized reagents [3]. |

| Reproducibility | Subject to instrument calibration and sample preparation; standardized protocols like MiFlow-Cyt EV improve consistency [17]. | Can be variable due to manual processes; reproducibility is enhanced by detailed protocol sharing [17] [16]. |

| Sample Type | Live or fixed cell suspensions (e.g., blood, PBMCs) [3]. | Lysates from tissue, cells, or whole organisms [3]. |

| Key Strengths | Single-cell resolution, multi-parametric analysis, reflects native antigen structure [3]. | Confirms protein molecular weight, strong evidence for antibody specificity [3]. |

| Common Pitfalls | Steric effects from fluorescent labels; requires viable cells and complex data analysis [17] [3]. | Protein denaturation means it is not ideal for conformational epitopes [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Western Blot Validation Protocol

A widely used method for validating antibody specificity in Western blot is the genetic strategy. The following protocol is adapted from established validation guidelines [16].

- Step 1: Sample Preparation

- Prepare protein lysates from both wild-type (control) cells and knockout (KO) cells where the target gene has been inactivated using CRISPR-Cas9 or RNAi.

- Step 2: Gel Electrophoresis and Transfer

- Separate the proteins from both lysates via SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions.

- Transfer the separated proteins onto a membrane.

- Step 3: Antibody Probing

- Incubate the membrane with the antibody being validated.

- Detect the signal using an appropriate chemiluminescent or fluorescent method.

- Step 4: Result Interpretation

- A specific antibody will show a clear band at the expected molecular weight in the wild-type sample and no corresponding band in the KO sample. Any signal present in the KO lane indicates cross-reactivity and non-specific binding [16].

Flow Cytometry Validation Protocol

For flow cytometry, validation must confirm the antibody performs reliably on native proteins in a complex cellular mixture. Key steps include titration and the use of proper controls [17].

- Step 1: Titration

- Perform a titration experiment to determine the optimal concentration of the fluorescently labeled antibody. This identifies the concentration that provides the best signal-to-noise ratio.

- Step 2: Instrument Calibration

- Calibrate the flow cytometer using standardized reference beads to ensure sensitivity and accuracy for the specific fluorescent labels used.

- Step 3: Control Selection

- Include both positive controls (cells known to express the target antigen) and negative controls (isotype controls or cells known not to express the target).

- Step 4: Specificity Confirmation

- For high-specificity validation, the antibody's signal in the positive control population should be distinct from the negative control. The use of KO cell lines as a negative control provides the most rigorous test of specificity [17].

Workflow Visualization

Antibody Validation Pathways

Flow Cytometry vs. Western Blot Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and tools essential for conducting rigorous antibody validation.

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Knockout (KO) Cell Lines | Serves as a critical negative control to confirm antibody specificity by providing a source material where the target protein is absent [15] [16]. |

| Validated Primary Antibodies | The core reagent under investigation; must be chosen based on application-specific validation data [3] [18]. |

| Fluorescent Secondary Antibodies | Used for detection in flow cytometry and fluorescent Western blotting; their quality directly impacts sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratio [16]. |

| Isotype Controls | Essential for flow cytometry to distinguish non-specific background binding from specific antibody signal [3]. |

| Reference Beads | Required for instrument calibration in flow cytometry to ensure sensitivity and quantitative accuracy are maintained [17]. |

| Antibody Validation Databases | Community resources (e.g., EV Antibody Database, Antibodypedia) that provide shared validation data to inform reagent selection and improve reproducibility [17]. |

The adherence to the core principles of specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility is non-negotiable for high-quality research using flow cytometry and Western blotting. As the market for research antibodies and validation tools continues to grow, the integration of standardized protocols, community data sharing, and advanced technologies like AI will be instrumental in elevating validation standards. For researchers, a methodical approach to antibody validation—using structured workflows, comparative data, and essential reagent tools—is the most effective strategy to ensure data integrity, accelerate discovery, and ultimately contribute to reliable scientific advancements.

In the realm of biomedical research, the validity of experimental data is fundamentally tied to the quality of the reagents used, with research antibodies being among the most critical. The reproducibility crisis, fueled in part by poorly characterized antibodies, underscores the necessity for rigorous, application-specific validation [19]. Validation is the experimental proof that an antibody is specific for its intended target and selective within the complex mixture of proteins in a sample, and its performance is highly dependent on the assay context [20]. An antibody that performs well in one application, such as Western blot, may not be suitable for another, like flow cytometry, due to differences in how the target protein is presented (denatured versus native) [3]. This guide provides a comprehensive overview of established validation strategies, comparing their application across flow cytometry and Western blot to empower researchers in selecting and implementing the most appropriate methods for their work.

Core Antibody Validation Strategies

The International Working Group for Antibody Validation (IWGAV) has proposed several pillars for antibody validation. A combination of these strategies is recommended for robust, reliable results [16].

Genetic Strategies (Knockout/Knockdown)

This approach is widely considered a "gold standard" for validating antibody specificity [20]. It involves measuring the antibody signal in control cells or tissues where the target protein has been eliminated or its expression significantly reduced.

- Methodology: For permanent knockout, CRISPR-Cas9 is used to disrupt the gene encoding the target protein [16]. For transient knockdown, RNA interference (RNAi), such as short interfering RNA (siRNA) or short hairpin RNA (shRNA), is employed to reduce protein levels [21]. The antibody is then used to probe lysates from these modified cells and their wild-type counterparts.

- Application in Western Blot: A specific antibody should show a single band at the expected molecular weight in the wild-type lane and a marked reduction or absence of this band in the knockout/knockdown lane. The presence of bands in the knockout lane indicates off-target binding [20] [16].

- Application in Flow Cytometry: The antibody's staining profile is compared between knockout and wild-type cells. A specific antibody will show a clear loss of signal in the knockout population. This is particularly powerful for confirming specificity in a native, cell-based assay [19] [22].

- Challenges: Knockout can be lethal for essential genes. Knockdown efficiency can be variable and depends on protein turnover rates, requiring confirmation at both the RNA and protein level [21].

Orthogonal Strategies

This method verifies antibody-based measurements by comparing them with data from an antibody-independent technique [16].

- Methodology: Protein expression levels quantified by the antibody-based method (e.g., Western blot band intensity or flow cytometry mean fluorescence intensity) are correlated with data from targeted mass spectrometry, quantitative PCR (for RNA expression), or pre-existing proteomic/transcriptomic datasets [21] [20].

- Application in Flow Cytometry: Antibody staining intensity for a protein across different cell types within a mixed population (e.g., leukocytes in blood) should correlate with the expected expression levels from RNA-seq or proteomic databases [21].

- Application in Western Blot: The protein abundance measured by Western blot across multiple cell lines or under different treatment conditions should align with data from resources like the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia or Human Protein Atlas [20].

- Limitations: Correlation does not prove causation, and mRNA levels may not always directly correlate with protein abundance due to post-transcriptional regulation [20].

Independent Antibody Strategies

This strategy uses two or more antibodies that recognize different, non-overlapping epitopes on the same target protein to confirm specificity [16].

- Methodology: Different antibody clones, ideally monoclonal antibodies binding to distinct linear or conformational epitopes, are used in the same application on identical samples [21] [20].

- Application: If all independent antibodies produce the same staining pattern (e.g., same banding pattern in Western blot or same population distribution in flow cytometry), confidence in the result is greatly increased. This is often used in conjunction with genetic strategies [20].

- Challenges: A major hurdle is that the precise epitope for many commercial antibodies is often unknown, making it difficult to confirm that the antibodies are truly independent [21].

Expression of Tagged Proteins

This approach validates an antibody by expressing the target protein with an affinity or fluorescent tag.

- Methodology: The target protein is expressed with a tag (e.g., FLAG, His, GFP) in a cell line that has low or no endogenous expression of the protein. The signal from the antibody under validation is then correlated with the signal from an anti-tag antibody or the fluorescent tag itself [21] [16].

- Application in Flow Cytometry: Cells transfected with a GFP-tagged protein can be analyzed by flow cytometry. A specific antibody should show a strong correlation between its signal and the GFP fluorescence intensity [21].

- Limitations: Overexpression can lead to non-physiological conditions and may mask low-level off-target binding. Furthermore, finding a cell line completely devoid of endogenous expression can be challenging [21].

Comparative Analysis of Validation by Application

The choice and implementation of validation strategies are heavily influenced by the specific assay. The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics and validation priorities for Western blot and flow cytometry.

Table 1: Comparative Assay Profiles and Validation Focus

| Parameter | Western Blot | Flow Cytometry |

|---|---|---|

| Target State | Denatured, linear epitopes [3] | Native, conformational epitopes [3] |

| Sample Type | Cell or tissue lysates [3] | Live or fixed cell suspensions [3] |

| Key Strength | Confirms protein size & detects isoforms [3] | Single-cell analysis of complex populations [3] |

| Primary Validation Concern | Specificity for the protein of expected molecular weight [20] | Specificity in a native state and minimal non-specific binding [19] |

| Optimal Validation Strategy | Genetic knockout (CRISPR/siRNA) is the gold standard to confirm a single band at the correct size [20]. | Correlation with known expression patterns in primary cells and genetic strategies [21] [19]. |

Table 2: Application of Validation Strategies Across Techniques

| Validation Strategy | Western Blot Protocol & Data Output | Flow Cytometry Protocol & Data Output |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic (KO/KD) | Protocol: Compare lysates from KO (e.g., via CRISPR) and wild-type cells. Output: Loss of the specific band in the KO lane on the blot confirms specificity [20]. | Protocol: Stain KO and wild-type cells with the target antibody. Output: Loss of fluorescence signal in the KO population by flow cytometry histogram confirms specificity [19] [22]. |

| Orthogonal | Protocol: Correlate Western blot band intensity with protein quantification from mass spectrometry across multiple cell lines. Output: A positive correlation coefficient supports antibody specificity [20]. | Protocol: Correlate antibody staining intensity (MFI) with RNA-seq expression data across different cell types in a mixed sample. Output: Matching staining intensity with expected expression patterns supports specificity [21]. |

| Independent Antibodies | Protocol: Probe the same membrane with two antibodies against different epitopes of the same protein. Output: Concordant banding patterns at the expected molecular weight increase confidence [20] [16]. | Protocol: Stain cells with two different antibody clones targeting the same protein. Output: Similar staining patterns and population distributions across samples support specificity [21]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and implementing these validation strategies.

Validation Strategy Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful antibody validation relies on access to well-defined reagents and resources. The following table details key materials and tools essential for implementing the strategies discussed.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Antibody Validation

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Validation | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Creates permanent knockout cell lines to confirm antibody specificity by the absence of the target protein. | Enables a gold-standard genetic validation approach [20]. |

| siRNA/shRNA Reagents | Provides transient knockdown of target protein expression for validation. | Requires optimization of transfection and confirmation of knockdown efficiency at RNA and protein levels [21]. |

| Recombinant Antibodies | Defined sequence ensures consistency, unlimited supply, and reduced batch-to-batch variation, enhancing reproducibility. | Superior to traditional hybridoma-derived monoclonals for long-term reproducibility [20] [19]. |

| Validated Positive/Negative Cell Lines | Serves as essential controls for both flow cytometry and Western blot validation. | Negative cell lines (e.g., KO) are crucial for establishing specificity; positive lines confirm assay functionality [19] [22]. |

| Protein/Omics Databases | Provides independent expression data for orthogonal validation strategies. | Resources like Human Protein Atlas, Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE), and Expression Atlas [20]. |

| HLDA Workshop Data | Provides externally validated information on antibody clones, particularly for cell surface markers (CD molecules) on human leukocytes. | Human Cell Differentiation Molecules (HCDM) workshops characterize and designate CD markers [21]. |

Rigorous antibody validation is not an optional step but a fundamental requirement for generating credible and reproducible scientific data. As demonstrated, a multi-faceted approach is most effective, leveraging strategies such as genetic knockouts, orthogonal assays, and independent antibodies to build a compelling case for antibody specificity. The optimal validation pathway is inherently application-specific; confirming an antibody for Western blot requires demonstrating specificity against a denatured protein of the correct molecular weight, while validation for flow cytometry must establish specific binding in a native, cellular context with minimal non-specific background. By systematically implementing these strategies and utilizing the growing repository of well-defined reagents and open-source antibody initiatives, the scientific community can collectively enhance the reliability of research findings and foster a more robust and reproducible biomedical research ecosystem.

Standardized Protocols for Flow Cytometry and Western Blot Validation

The reproducibility of biomedical research relying on antibody-based techniques has been persistently challenged, with an estimated 85% of research funds potentially wasted due to poor science and substandard reagents [23]. This reproducibility crisis has catalyzed a fundamental shift in how researchers approach antibody validation, moving from generic claims of antibody validation to a more nuanced "fit-for-purpose" mindset [24]. This approach recognizes that antibody specificity is inherently context-dependent—an antibody validated for one application may perform poorly in another due to differences in sample preparation, detection methods, and biological context [24] [25].

Within this framework, selecting the appropriate analytical platform becomes paramount. Flow cytometry and western blotting represent two foundational techniques for protein detection and analysis, yet they serve distinct purposes and possess unique strengths and limitations. Understanding these differences enables researchers to align their methodological choices with specific research questions, ensuring that data interpretation rests on a solid technical foundation. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these techniques within the fit-for-purpose validation paradigm, empowering researchers to make informed decisions that enhance experimental reliability and reproducibility.

Flow Cytometry vs. Western Blot: A Technical Comparison

The choice between flow cytometry and western blot involves fundamental trade-offs between cellular resolution, multiplexing capability, throughput, and analytical context. The table below summarizes their core characteristics:

| Feature | Flow Cytometry | Western Blot |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Resolution | Single-cell level [26] | Population average (lysate) [26] |

| Throughput | High (thousands of cells/second) [26] | Low to medium [26] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (multiple parameters simultaneously) [26] | Low (typically one protein at a time) [26] |

| Sample Type | Whole cells (suspension) [26] | Cell lysates (denatured) [25] |

| Protein State Analyzed | Native (for surface markers) or fixed (intracellular) [25] | Denatured [25] |

| Key Strength | Detects heterogeneity and rare cell populations [26] | Confirms molecular weight and total protein expression |

| Assay Duration | 2-4 hours [26] | 1-2 days [26] |

Decision Workflow: Selecting the Right Technique

The following diagram outlines a logical decision process for selecting between flow cytometry and western blot based on core experimental goals:

Experimental Evidence: Quantitative Comparisons

Empirical data from direct methodological comparisons reinforces the importance of fit-for-purpose selection, demonstrating that the optimal technique varies significantly with the biological question.

Detecting Signaling Events and Heterogeneity

A direct comparison for analyzing cellular signaling highlights flow cytometry's advantages for complex, heterogeneous systems. When studying heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) induction, both methods showed excellent agreement in quantifying overall expression levels [27]. However, flow cytometry provided the crucial additional insight that Hsp72 induction was cell-cycle-dependent, predominantly occurring in early S-phase cells—a nuance impossible to detect by western blot's population average [27].

Clinical Carrier Detection Sensitivity

In clinical diagnostics, the choice of method directly impacts sensitivity. A study on Glanzmann Thrombasthenia carrier detection evaluated both techniques against DNA mutation analysis as the gold standard [28]. The results were striking:

| Technique | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Cytometry | 75% | Not specified | More effective for carrier detection due to quantitative surface protein measurement [28] |

| Western Blot | 39% | Not specified | Lower sensitivity likely due to inability to detect all mutant forms [28] |

Antibody Concordance Across Platforms

The context-dependency of antibody performance is evident in PD-L1 biomarker studies. A quantitative comparison of six anti-PD-L1 antibodies showed high concordance (R²: 0.76-0.99) when tested on controlled cell lines using chromogenic detection [29]. However, concordance was lower in tumor tissue specimens (R² as low as 0.42 for some clones), highlighting how tissue heterogeneity, sample processing, and the cellular microenvironment significantly impact antibody binding and detection [29].

Fit-for-Purpose Antibody Validation Protocols

Foundational Principles

Effective antibody validation rests on several conceptual pillars that should be applied based on the intended application [25]:

- Genetic Strategies: Using CRISPR-Cas9 knockout or siRNA knockdown cells to confirm loss of antibody signal, demonstrating specificity [25].

- Independent Antibodies: Employing two antibodies recognizing different epitopes on the same target to confirm identical staining patterns [25].

- Tagged Protein Expression: Comparing detection of endogenously expressed protein with an antibody against a genetic tag (e.g., GFP, FLAG) [25].

Application-Specific Validation Workflow

The "fit-for-purpose" mindset requires demonstrating antibody specificity within a defined experimental design [24]. The following workflow is adaptable for both flow cytometry and western blot:

For flow cytometry specifically, incorporating true negative cell-type controls is critical. One study evaluating seven anti-troponin antibody clones with different preparation protocols found that sample preparation had cell-type and antibody clone-dependent effects. In some cases, signal above the isotype control was observed in negative cell types, revealing non-specific binding that would have been misinterpreted without proper negative controls [24]. The mixed population experiment, where defined ratios of positive and negative cells are analyzed, provides the ultimate assessment of a flow cytometry protocol's ability to accurately quantify population heterogeneity [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of either technique requires high-quality, well-characterized reagents. The following table details key solutions:

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibodies | High specificity to a single epitope; ensures lot-to-lot consistency [25]. | Critical for flow cytometry multiplexing. Recombinant antibodies offer superior sequence-defined reproducibility [25]. |

| Recombinant Antibodies | Sequence-defined antibodies produced recombinantly; eliminate genetic drift of hybridomas [25]. | Ideal for long-term studies; sequence knowledge enables advanced validation methods. |

| Isotype Controls | Assess non-specific antibody binding in flow cytometry [24]. | Necessary but insufficient alone; must be paired with negative cell-type controls for rigorous validation [24]. |

| Cell Line Controls (Knockout/Knockdown) | Genetically engineered cells lacking the target protein; serve as true negative controls [25]. | Essential for demonstrating antibody specificity via genetic strategies. |

| Proteotypic Peptides | Surrogate peptides uniquely representing the target protein (e.g., for IgG) [30]. | Used in mass spectrometry-based absolute quantitation methods like MASCALE to convert arbitrary ELISA units to absolute antibody amounts [30]. |

| Reference Standard Serum | Calibrates binding antibody assays across runs and laboratories [30]. | Enables relative quantitation; matrix should match the sample type (e.g., human serum for clinical samples) [30]. |

The journey toward more reproducible and reliable research begins with a fit-for-purpose approach to antibody validation. There is no universal "best" technique—only the most appropriate technique for a specific biological question. Flow cytometry excels when analyzing complex cell populations, detecting rare events, and performing multiparameter analysis at single-cell resolution. Western blot remains valuable for confirming protein identity based on molecular weight and analyzing samples where cell integrity cannot be maintained. By rigorously validating antibodies within their specific research context and aligning methodological strengths with experimental goals, researchers can generate robust, interpretable, and reproducible data that advances scientific discovery and drug development.

Flow cytometry is an indispensable tool in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics, enabling high-throughput, multiparametric analysis at the single-cell level [31]. The technology's versatility allows applications from basic research to clinical diagnosis and monitoring of hematological malignancies [32] [31]. However, this power comes with complexity, and the reliability of flow cytometry data hinges on rigorous method validation. For researchers working across flow cytometry and Western blot platforms, understanding validation requirements is essential for generating reproducible, reliable data. This guide provides a comprehensive framework for validating flow cytometry methods, from limited research applications to full clinical validation, within the broader context of research antibody validation.

The Fundamentals of Flow Cytometry Validation

Method validation for flow cytometry establishes documented evidence that a specific assay consistently performs as intended for its intended use [33]. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) H62 guideline, released in 2021, provides recommendations for platform workflow, instrument setup, standardization, assay development, and fit-for-purpose analytical method validation [33]. The extent of validation required depends on the assay's application, with increasingly stringent requirements as methods transition from basic research to clinical diagnostics.

Key Validation Parameters Across Applications

Table 1: Core Validation Parameters for Different Application Levels

| Validation Parameter | Research Use | Laboratory-Developed Test (LDT) | Full Clinical Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision/Reproducibility | Limited replicate testing (n=3-5) | Within-run, between-run, between-operator | Comprehensive per CLSI H62 guidelines [33] |

| Accuracy | Comparison to known positive/negative controls | Method comparison with reference standard | Deming regression against gold standard method |

| Sensitivity | Limit of detection estimation | Formal limit of detection/quantification | Clinically relevant detection limits established [34] |

| Specificity | Negative control assessment | Interference testing | Cross-reactivity with similar antigens tested |

| Linearity | Not typically required | Dilutional linearity | Full reportable range verification |

| Reference Range | Not typically required | Preliminary establishment | Clinically validated reference intervals |

| Robustness | Informal assessment | Controlled variability testing | Formal robustness testing per guidelines |

Step-by-Step Validation Framework

Step 1: Define Intended Use and Validation Scope

The foundation of any validation is a clear definition of the assay's intended use. For research antibodies, this includes determining whether the assay will be used for qualitative identification of cell populations, semi-quantitative assessment of marker expression, or fully quantitative measurements [31]. This definition directly impacts the extent of validation required.

Step 2: Instrument Qualification and Standardization

Before assay validation, ensure proper instrument performance:

- Daily Quality Control: Perform using calibration beads to verify laser delays, fluidics, and optical alignment

- Standardization: Implement procedures to minimize inter-instrument and inter-laboratory variability, which is particularly important for multicenter studies [31]

- Optical Configuration: Confirm that laser wavelengths and filter configurations match fluorochrome requirements

Step 3: Assay Development and Optimization

Develop standardized protocols for critical pre-analytical and analytical steps:

- Sample Preparation: Optimize cell extraction procedures, particularly for complex tissues like brain with high lipid content and autofluorescence [35]

- Antibody Titration: Determine optimal antibody concentrations using serial dilutions to achieve best signal-to-noise ratio

- Panel Design: Ensure fluorochrome compatibility and minimize spectral overlap

- Controls: Include positive, negative, and process controls for each experiment

Step 4: Analytical Validation

The extent of analytical validation depends on the intended use level defined in Step 1:

For Research Applications:

- Precision: Assess through limited repeatability testing (3-5 replicates)

- Specificity: Verify using isotype controls and knockout/knowndown samples where available

- Sensitivity: Determine lower limits of detection for rare cell populations

For Clinical Applications:

- Comprehensive Precision Studies: Evaluate within-run, between-run, and between-operator precision following CLSI H62 recommendations [33]

- Method Comparison: Perform against gold standard methods when available

- Interference Studies: Test potential interferents like hemoglobin, lipids, and medications

- Reportable Range: Establish through dilutional linearity studies

Step 5: Validation of Modified Assays

When modifying previously validated assays, the extent of re-validation should match the significance of the change:

Table 2: Validation Requirements for Common Assay Modifications

| Modification Type | Examples | Recommended Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Minor Change | New lot of validated antibody | Limited verification (precision, comparison) |

| Moderate Change | New fluorochrome, new antibody | Partial validation (precision, accuracy, sensitivity) |

| Major Change | New panel tube, new instrument platform | Full validation (all parameters) |

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Studies

Protocol 1: Precision Testing for Clinical Flow Cytometry Assays

- Sample Preparation: Select at least three samples with low, medium, and high expression of target antigens

- Testing Schedule: Run replicates within the same batch (within-run), across different days (between-run), and by different operators (between-operator)

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation for each level

- Acceptance Criteria: Establish based on biological variation and clinical requirements; typically ≤15% CV for high-expression markers and ≤20% CV for low-expression markers

Protocol 2: Sensitivity and Limit of Detection Studies

- Cell Line Serial Dilutions: Spike target cells into normal matrix at decreasing frequencies (e.g., 1%, 0.1%, 0.01%)

- Sample Processing: Process a minimum of 12 replicates at each concentration level

- Data Analysis: Determine the lowest concentration where the target population is consistently detected with ≥95% probability

- Clinical Correlation: For MRD detection, verify that the limit of detection meets clinical needs (typically 0.01% for leukemia MRD) [34]

Protocol 3: Method Comparison for Accuracy Assessment

- Sample Selection: Collect a representative set of clinical samples (n=20-40) covering the assay's measuring range

- Parallel Testing: Run all samples using both the new method and reference method within clinically relevant timeframes

- Statistical Analysis: Perform correlation analysis, Deming regression, and Bland-Altman plots

- Acceptance Criteria: Establish based on intended use; for clinical diagnostics, bias should not exceed clinically significant limits

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Flow Cytometry Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Validation Antibodies | CD45, CD3, CD19, CD34 | Process controls and population identification [31] |

| Isotype Controls | Mouse IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b | Assessing non-specific binding and background signal |

| Viability Dyes | 7-AAD, DAPI, propidium iodide | Excluding dead cells from analysis [35] |

| Calibration Beads | Rainbow beads, UV beads | Instrument performance tracking and standardization |

| Compensation Beads | Anti-mouse/rat Ig beads | Calculating spectral overlap between channels |

| Cell Preparation Reagents | Collagenase, papain, Percoll | Tissue dissociation and cell isolation [35] |

Workflow Visualization

Flow Cytometry Validation Workflow: This diagram illustrates the step-by-step validation process based on assay intended use, showing increasing complexity from research to clinical applications.

Application in Real-World Research Contexts

Case Study: Swiss Mouse MHC Antibody Validation

A 2025 study demonstrates research-level validation of anti-MHC antibodies for flow cytometry in Swiss mice. Researchers systematically tested multiple antibody clones (28-14-8, 34-1-2, MK-D6, N22) to identify those suitable for analyzing MHC class I and II molecules in the H2-q haplotype [36]. This validation included:

- Specificity testing across different mouse strains

- Application in immunopeptidomics studies

- Cross-validation with mass spectrometry data

The study highlights how research antibody validation enables new applications in previously uncharacterized model systems.

Implementation in Resource-Limited Settings

Validation approaches can be adapted to various resource settings. The "MRDLite" assay demonstrates how simplified flow cytometry panels can be validated for clinical use in low-resource environments [34]. This minimal residual disease detection assay uses only four antibodies but still provides sufficient predictive power for risk stratification in acute lymphoblastic leukemia when properly validated.

Integration with Broader Research Context

Flow cytometry validation should be integrated with overall research antibody validation strategies. Key considerations include:

- Cross-Platform Validation: Verify antibody performance across flow cytometry, Western blot, and immunohistochemistry

- Lot-to-Lot Consistency: Establish procedures to address variability between different antibody lots

- Stability Studies: Determine reagent shelf-life under various storage conditions

- Documentation: Maintain comprehensive records for reproducibility and regulatory compliance

Flow cytometry method validation is a graded process that should be commensurate with the assay's intended use. From limited validation for basic research to comprehensive validation for clinical diagnostics, a structured approach ensures reliable, reproducible results. By implementing these step-by-step validation procedures and leveraging appropriate controls and reagents, researchers can generate high-quality data that advances scientific understanding and improves patient care. The integration of flow cytometry validation with broader research antibody validation frameworks further enhances experimental reproducibility across platforms.

Western blotting, also known as immunoblotting, is a fundamental technique in biomedical research that uses antibodies to detect specific proteins from a complex mixture that has been separated by gel electrophoresis [5] [37]. This method allows researchers to determine critical protein characteristics including size, relative abundance, and post-translational modifications [5]. In the context of validation research for antibodies used in both flow cytometry and Western blotting, proper optimization of this technique is essential for generating reproducible and reliable data [20]. The specificity of the antibody-antigen interaction enables a target protein to be identified amidst a complex protein mixture, producing both qualitative and semi-quantitative data about the protein of interest [38]. With growing concerns about the reproducibility of research findings, particularly relating to antibody performance, rigorous optimization and validation of Western blot protocols have become increasingly important across the global life sciences community [20].

Theoretical Foundations of Western Blot Optimization

Historical Development and Technical Principles

The Western blot technique was developed in the late 1970s, building upon earlier blotting methods for DNA (Southern blot) and RNA (northern blot) [5]. W. Neal Burnette first described the method in 1981, originally naming it "western blot" in recognition of its predecessors [5]. The technique relies on three fundamental elements: (1) separation of proteins by size through gel electrophoresis, (2) transfer of separated proteins to a solid support membrane, and (3) immunodetection of target proteins using specific antibodies [37]. The standard workflow involves preparing a protein-containing sample from cells or tissues, separating proteins using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) under denaturing conditions, transferring proteins to a membrane, blocking the membrane to prevent nonspecific antibody binding, incubating with primary and secondary antibodies, and finally detecting the signal [5] [38]. Each of these steps offers opportunities for optimization to improve sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility, particularly when comparing antibody performance across different immunoassay platforms such as Western blot and flow cytometry [20] [21].

Critical Optimization Parameters for Protein Detection

Optimizing a Western blot protocol requires careful consideration of multiple interconnected parameters that collectively influence the signal-to-noise ratio and detection sensitivity. For low-abundance proteins like tissue factor (TF), each step in the Western blotting process requires systematic optimization, including blocking conditions, detection methods, and antibody selection [39]. The formulation of the lysis buffer must be tailored to the subcellular location of the target protein and the nature of the antibody's epitope [5]. Transfer efficiency varies significantly among proteins based on their ability to migrate out of the gel and their propensity to bind to the membrane under specific conditions [38]. Blocking buffers play a crucial role in improving assay sensitivity by reducing background interference, with various agents ranging from milk to highly purified proteins offering different advantages depending on the specific antibody-antigen pair [38]. Recent innovations include the "sheet protector strategy" which uses minimal antibody volumes (20-150 µL for mini-sized membranes) while maintaining sensitivity and specificity comparable to conventional methods [40]. This approach also enables faster detection times and incubation at room temperature without agitation [40].

Comprehensive Methodologies for Western Blot Optimization

Protein Extraction and Sample Preparation Protocols

Proper protein extraction and sample preparation are critical first steps in Western blot optimization. For adherent cells, the protocol begins with washing cells in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and dislodging them using a cell scraper [37]. After centrifugation, the cell pellet is resuspended in ice-cold cell lysis buffer containing fresh protease inhibitor cocktail to prevent protein degradation [37]. The lysate is incubated on ice for 30 minutes, then clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 RPM for 10 minutes at 4°C [37]. The supernatant containing the soluble protein fraction is transferred to a fresh tube for immediate use or storage at -80°C [37]. For tissue samples, which display a higher degree of structure, mechanical disruption such as homogenization or sonication is typically required to extract proteins effectively [37]. The choice of lysis buffer depends on the subcellular location of the target protein and whether the antibody recognizes the protein in its native or denatured state [5]. For example, NP-40 or Triton X-100-containing buffers are suitable for whole cell extracts, while RIPA buffer, which contains SDS, is better for preparing membrane-bound and nuclear extracts but disrupts protein-protein interactions [5]. Following extraction, protein concentration must be accurately determined using colorimetric or fluorescent-based assays such as BCA or Bradford assays to ensure equal loading across gel wells [5].

Gel Electrophoresis and Protein Transfer Methods

Protein separation by gel electrophoresis represents a core component of the Western blot technique. The standard approach uses discontinuous polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) with a stacking gel (pH 6.8, lower acrylamide concentration) and a separating gel (pH 8.8, higher polyacrylamide content) [37]. Samples are prepared in loading buffer containing glycerol to increase density and bromophenol blue to track migration, then heated to denature higher-order structures while retaining sulfide bridges [37]. The gel is connected to a power supply and run at low voltage (60V) through the separating gel and higher voltage (140V) through the stacking gel until the dye front approaches the bottom of the gel [37]. Following electrophoresis, proteins are transferred to a solid support membrane, typically nitrocellulose or polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF), using electrophoretic transfer [38]. The transfer apparatus creates a "sandwich" with sponge, filter papers, gel, and membrane, positioned such that the membrane is between the gel and the positive electrode to facilitate migration of negatively charged proteins [37] [38]. Transfer efficiency depends on multiple factors including gel composition, complete gel-membrane contact, transfer time, protein size and composition, field strength, and the presence of detergents and alcohol in the buffer [38]. After transfer, total protein on the membrane can be assessed with reversible stains like Ponceau S to confirm transfer efficiency before proceeding with immunodetection [38].

Antibody Incubation and Detection Systems

Antibody incubation and detection represent the final critical phase in Western blot optimization. The membrane is first blocked to prevent nonspecific antibody binding, with 5% skim milk being a common blocking agent, though commercial blocking buffers often provide superior performance for specific applications [37] [38]. For conventional antibody incubation, the blocked membrane is placed in a container with primary antibody solution (typically 10 mL) and incubated with agitation at 4°C overnight [40]. The membrane is then washed with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) to remove unbound antibodies [37]. For detection, most researchers prefer the indirect method which uses an unlabeled primary antibody followed by an enzyme- or fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody, offering signal amplification and a wide selection of labeled secondary antibodies [38]. The sheet protector strategy provides an innovative alternative for antibody incubation, requiring only 20-150 µL of antibody solution distributed over the membrane as a thin liquid layer between sheet protector leaflets [40]. This approach produces comparable sensitivity and specificity to conventional methods while significantly reducing antibody consumption and enabling room temperature incubation without agitation [40]. Detection is typically achieved using chemiluminescent substrates for horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibodies, though fluorescently tagged antibodies are growing in popularity for their multiplexing capabilities [38].

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional vs. Sheet Protector Antibody Incubation Methods

| Parameter | Conventional Method | Sheet Protector Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody Volume | 10 mL | 20-150 µL |

| Incubation Conditions | 4°C with agitation overnight | Room temperature without agitation |

| Detection Time | Several hours | Minutes to a few hours |

| Sensitivity | Standard | Comparable to conventional |

| Equipment Needs | Standard lab equipment | Sheet protector (common stationery) |

| Practical Applications | Routine Western blotting | Ideal for rare/expensive antibodies |

Experimental Design for Antibody Validation

Well-designed antibody validation is essential for reproducible Western blot results [20]. The International Working Group for Antibody Validation (IWGAV) recommends multiple strategies to confirm antibody specificity, including genetic controls, independent-epitope strategies, orthogonal methods, and the use of multiple cell lines [20]. Knockout (KO) validation is considered the "gold standard" for Western blotting, where the absence of signal in cells lacking the target gene confirms antibody specificity [20]. When knockout studies are not feasible, RNA interference (RNAi) provides an alternative approach, though careful experimental design is required to confirm efficient knockdown at both RNA and protein levels [21]. Additional validation methods include correlation with RNA or proteomic data from multiple cell lines with different expression levels, and detection of overexpressed tagged or untagged protein [21]. Proper controls are essential throughout validation experiments, including positive controls (cell lines known to express the target protein) and negative controls (null cell lines) to confirm that staining is not nonspecific [20] [37]. For phospho-specific antibodies, additional validation steps are necessary to confirm specificity for the modified protein [20]. Researchers should also be aware of batch-to-batch variation in antibody production, with recombinant antibodies generally offering greater consistency compared to polyclonal antibodies [20].

Table 2: Antibody Validation Methods for Western Blotting

| Validation Method | Experimental Approach | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Controls (KO) | Compare signal in wild-type vs. knockout cell lines | Considered "gold standard"; requires appropriate cell lines |

| Independent Epitopes | Use multiple antibodies targeting different epitopes of same protein | Confirms specificity if similar patterns observed |

| Orthogonal Methods | Compare with antibody-independent methods (e.g., mass spectrometry) | Provides confirmation through different technical principles |

| Multiple Cell Lines | Test antibody across cell lines with different expression levels | Expression pattern should match expected profile |

| RNAi/Knockdown | Reduce target expression using siRNA or shRNA | Confirm efficient knockdown at RNA and protein levels |