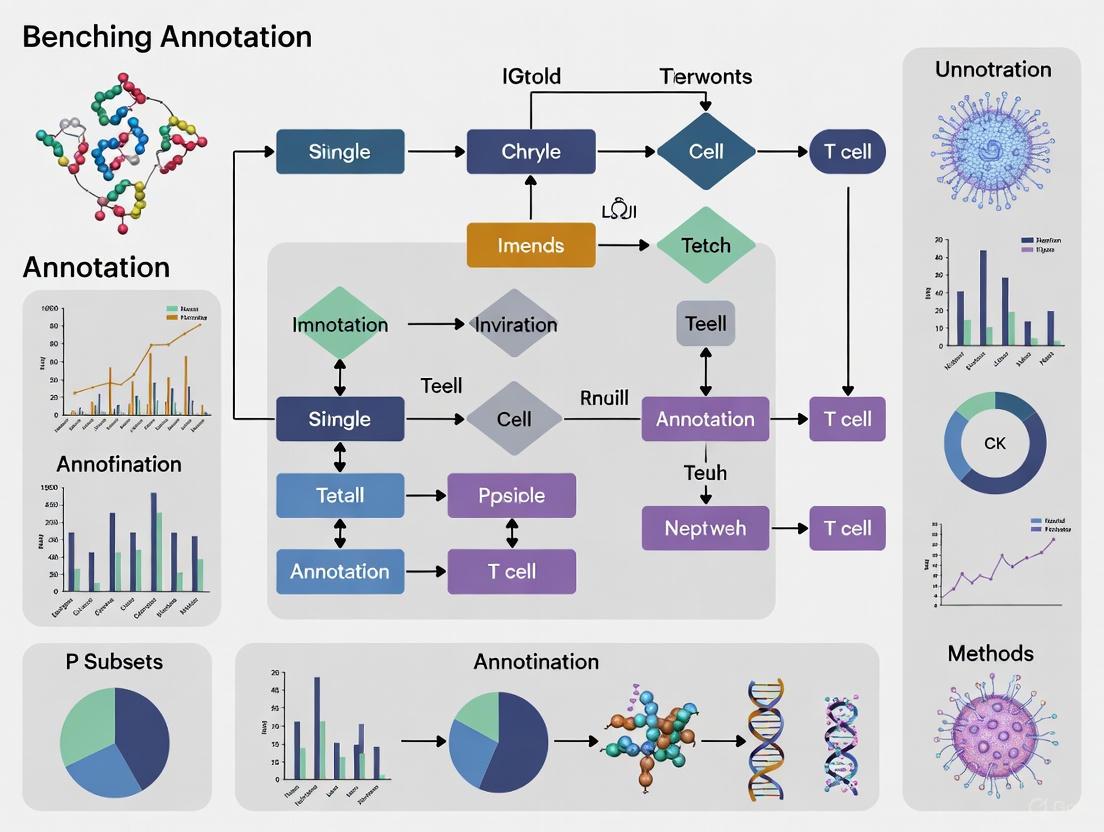

Benchmarking Single-Cell Annotation Methods for T Cell Subsets: A Comprehensive Guide for Immunologists and Bioinformaticians

This comprehensive review examines the current landscape of computational methods for annotating T cell subsets in single-cell RNA sequencing data.

Benchmarking Single-Cell Annotation Methods for T Cell Subsets: A Comprehensive Guide for Immunologists and Bioinformaticians

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines the current landscape of computational methods for annotating T cell subsets in single-cell RNA sequencing data. As T cells exhibit remarkable heterogeneity with continuously varying states rather than discrete subsets, accurate annotation remains challenging yet crucial for understanding immune responses in cancer, autoimmunity, and infectious diseases. We synthesize findings from recent benchmarking studies and methodological advances, covering foundational concepts, practical implementation of tools like TCAT, STCAT, SingleR, and Azimuth, troubleshooting common challenges, and validation strategies. The article provides researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based guidance for selecting, implementing, and validating annotation approaches across diverse experimental contexts, with particular emphasis on emerging methods incorporating gene expression programs, multimodal data, and foundation models.

Understanding T Cell Heterogeneity and Annotation Challenges in Single-Cell Genomics

T cells are a cornerstone of the adaptive immune system, traditionally categorized into discrete, mutually exclusive subsets such as CD4+ helper T cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and various helper lineages (Th1, Th2, Th17) based on their surface markers, transcription factors, and cytokine profiles [1] [2]. This classical model has provided a valuable framework for understanding immune function in host defense, autoimmune diseases, and cancer [1]. However, the advent of high-resolution single-cell technologies has revealed a far more complex picture. Emerging evidence now conflicts with this canonical model, indicating that T cell states vary continuously, combine additively within a single cell, and exhibit significant plasticity in response to stimuli [3] [4]. This continuum of states challenges the traditional discrete classification and necessitates new analytical frameworks for characterizing T cell biology, with profound implications for both basic research and therapeutic development [3].

This guide objectively compares the predominant methodologies used to define T cell subsets and states, benchmarking their performance, underlying protocols, and applicability in research and drug development. We focus specifically on the contrast between traditional discrete clustering and emerging component-based models, providing the experimental data and quantitative comparisons essential for researchers to select appropriate tools for their work.

Methodological Comparison: Discrete Clustering vs. Component-Based Models

The analysis of T cell identity has been revolutionized by single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). The predominant analytical approach has been clustering, which groups cells based on transcriptional similarity. However, newer component-based models like nonnegative matrix factorization (NMF) model a cell's transcriptome as an additive mixture of gene expression programs (GEPs) [3] [4]. The table below provides a direct comparison of these two methodologies.

Table 1: Benchmarking Discrete Clustering vs. Component-Based Models for T Cell Analysis

| Feature | Discrete Clustering (e.g., Phenograph, Seurat) | Component-Based Models (e.g., cNMF, TCAT) |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Model of Cell Identity | Assumes cells belong to discrete, mutually exclusive groups [3]. | Models cell identity as a continuous mixture of overlapping gene expression programs (GEPs) [3] [4]. |

| Handling of Co-Expressed Programs | Poor; proliferating cells from different lineages often cluster together, obscuring their origins [3]. | Excellent; explicitly quantifies the simultaneous activity of multiple GEPs (e.g., lineage + activation) within a single cell [3]. |

| Representation of Continuous States | Forces continuous transitions into arbitrary discrete groups, losing information [4]. | Naturally captures continuous variation and plastic transitions between states [3] [4]. |

| Cross-Dataset Reproducibility | Low; cluster labels and boundaries are often dataset-specific [3]. | High; GEPs serve as a fixed coordinate system for comparing cells across different studies [3]. |

| Identification of Rare Populations | Challenging; rare populations may be merged into larger clusters. | Effective; can quantify rarely used GEPs even in small query datasets [3]. |

| Key Limitations | Obscures multilayered biology and continuous variation [3]. | Requires a well-defined reference catalog of GEPs for optimal performance. |

Quantitative Benchmarking of the TCAT Pipeline

The T-CellAnnoTator (TCAT) pipeline is a specific instantiation of the component-based model designed for scalable and reproducible T cell analysis. It was benchmarked on a massive dataset of 1.7 million T cells from 700 individuals across 38 tissues and five disease contexts (COVID-19, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and healthy) [3] [4]. The following performance data provides a quantitative basis for its evaluation.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of the TCAT (starCAT) Pipeline

| Metric | Performance Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reproducibility of GEPs | 9 GEPs were identified across all 7 analyzed datasets (Mean Pearson R = 0.81) [3]. | Analysis of 7 independent scRNA-seq datasets [3]. |

| Catalog Size | 46 consensus GEPs (cGEPs) identified [3]. | 27-36 more GEPs than prior analyses [3]. |

| GEP Concordance | 49 cGEPs were reproducible across 2 or more datasets (Mean R = 0.74) [3]. | Significantly higher concordance than PCA-based methods [3]. |

| Prediction Accuracy | Pearson R > 0.7 for inferring GEP usage in query datasets [3]. | Benchmarking simulations with partially overlapping reference/query GEPs [3]. |

| Performance on Small Datasets | Maintains constant performance; accurately quantifies rare GEPs in queries as small as 100 cells [3] [4]. | Simulation of query datasets of 100 to 100,000 cells [3]. |

| Discriminative Power | Achieved 86.2% accuracy, 85.7% sensitivity, and 80.9% specificity in distinguishing RA subtypes [5]. | Analysis of 50 participants using FlowSOM clustering and SVM [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Single-Cell T Cell Annotation

Workflow for Traditional Clustering-Based Analysis

The following diagram outlines the standard protocol for analyzing T cells via discrete clustering, commonly used with flow cytometry or scRNA-seq data.

Protocol Details:

- Sample Collection & Processing: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or tissues are collected and processed into single-cell suspensions. For tissue, this involves manual dissociation and enzymatic digestion (e.g., using human tumor dissociation enzymes and a gentleMACS dissociator) [6].

- Cell Staining & Acquisition: Cells are stained with fluorescently-labeled antibodies targeting surface markers (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD45RO, CCR7) and intracellular proteins (FOXP3, cytokines). Data is acquired via flow cytometers or, for higher dimensionality, mass cytometers (CyTOF) or spectral flow cytometers [5] [6].

- Computational Analysis: Dimensionality reduction is performed followed by application of clustering algorithms. Cells are grouped based on transcriptional or protein marker similarity.

- Cluster Annotation & Assignment: Resulting clusters are manually annotated based on canonical marker expression (e.g., CD4+FOXP3+ for Tregs), and each cell is assigned to a single, discrete subset [5].

Workflow for Component-Based GEP Analysis (TCAT/starCAT)

The TCAT/starCAT pipeline provides an alternative, component-based workflow for T cell annotation, as illustrated below.

Protocol Details:

- Reference Catalog Construction: Multiple large-scale scRNA-seq datasets are aggregated and batch-corrected using modified algorithms (e.g., Harmony) that produce non-negative, gene-level corrected data compatible with cNMF [3] [4].

- GEP Discovery with cNMF: Consensus Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (cNMF) is applied to learn GEP "spectra" (gene weights) and "usages" (their contribution to each cell's transcriptome). The algorithm is run multiple times to ensure robustness [3].

- Consensus GEP (cGEP) Definition: GEPs from different datasets are clustered based on correlation, and a final catalog of consensus GEPs (cGEPs) is defined as the average of each cluster. The published catalog contains 46 cGEPs [3].

- Projection onto Query Data: For a new query dataset, the pre-defined cGEPs are projected onto each cell using non-negative least squares (NNLS) regression via the starCAT algorithm. This quantifies the usage of each cGEP in every cell, resulting in a continuous, multi-faceted identity profile [3] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details key reagents and computational tools essential for implementing the described experimental protocols.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for T Cell Subset Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescently-Conjugated Antibodies | Cell surface and intracellular protein detection for flow cytometry. | CD3, CD4, CD8, CD45RO, CCR7, CD25, FOXP3, CD161, HLA-DR, CD38 [5] [6]. |

| Cell Isolation & Dissociation Kits | Gentle extraction of viable immune cells from tissue for analysis. | Human tumor dissociation enzyme kits (Miltenyi Biotec); gentleMACS dissociator [6]. |

| Viability Stains | Discrimination of live/dead cells during flow cytometry analysis. | Live/Dead Fixable Blue (Invitrogen) or similar dyes [6]. |

| CITE-seq Antibodies | Integration of surface protein expression with transcriptomic data in scRNA-seq. | Oligo-conjugated antibodies for markers like PD-1, CD4, CD8 [3]. |

| Clustering Algorithms | Unsupervised identification of cell populations from high-dimensional data. | FlowSOM [5], Seurat clustering, Phenograph. |

| Component-Based Modeling Tools | Decomposing single-cell data into additive gene expression programs. | TCAT/starCAT [3], cNMF [3] [4], SPECTRA. |

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The shift from a discrete to a continuous model of T cell biology has direct consequences for immunotherapies. Engineered T cell therapies, such as CAR-T and TCR-T cells, are "living drugs" with complex pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [7] [8]. Their efficacy and toxicity are heavily influenced by the composition and differentiation state of the infused T cell product [8].

- Product Potency: The therapeutic success of CAR-T cells is linked to the presence of less-differentiated phenotypes like stem cell memory T (TSCM) and central memory T (TCM) cells, which have superior expansion potential and persistence in vivo compared to terminally differentiated effector T cells [8].

- Exposure-Response & Toxicity: Pharmacokinetic analysis of CAR-T cells reveals high inter-patient variability in exposure (Cmax and AUC), which correlates with both response and toxicity (e.g., cytokine release syndrome). A narrow therapeutic index is common, where exposure levels for efficacy overlap with those for toxicity [7].

- Overcoming Exhaustion: In cancer and chronic infections, T cells can adopt an "exhausted" state, characterized by upregulation of inhibitory receptors like PD-1, TIM-3, and LAG3, and impaired effector functions [1] [3]. New analytical frameworks can more precisely define this exhaustion state, separate from other activation programs, aiding the development of next-generation therapies that reverse or prevent T cell exhaustion [3].

The field of T cell biology is undergoing a foundational paradigm shift. The classical model of discrete, static subsets is being superseded by a more nuanced understanding of continuous, plastic states that can coexist within a single cell. This transition is driven by advanced single-cell technologies and, crucially, by the development of new computational frameworks like component-based models. As this guide has benchmarked, these new methods offer significant advantages in reproducibility, resolution, and biological relevance. For researchers and drug developers, embracing this continuous model is no longer optional but essential for unraveling the complexity of immune responses and designing the next generation of precise and effective T cell immunotherapies.

Limitations of Traditional Clustering for T Cell Annotation

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized immunology by enabling researchers to decipher the vast diversity and dynamic nature of T cells, which play critical roles in cancer, infection, and autoimmune diseases [3] [9]. A crucial step in analyzing scRNA-seq data involves annotating cell types—assigning biological identities to cells based on their gene expression profiles [9] [10]. For years, the predominant approach has relied on traditional clustering methods, which group cells based on similarity in their transcriptomes, followed by manual annotation of these clusters using known marker genes [3] [11] [12]. However, the increasing complexity of T cell biology has exposed significant limitations in this approach. This article examines these limitations within the broader context of benchmarking single-cell annotation methods, highlighting why new computational frameworks are necessary for accurate T cell subset identification in research and drug development.

Core Limitations of Traditional Clustering Methods

Traditional clustering methods, such as those implemented in popular tools like Seurat, discretize what is fundamentally a continuous biological reality [3]. The following table summarizes their primary shortcomings:

| Limitation | Impact on T Cell Annotation |

|---|---|

| Forced Discretization of Continuous States [3] | Obscures the true continuum of T cell states (e.g., between TH1, TH2, TH17), leading to an oversimplified and inaccurate representation of T cell phenotypes. |

| Inability to Resolve Co-expressed Gene Programs [3] | A single cell can activate multiple gene programs (GEPs) simultaneously (e.g., proliferation and cytotoxicity). Clustering often assigns cells to a single, dominant cluster, masking this functional complexity. |

| Failure to Delineate Canonical Subsets [3] [12] | Clustering often fails to identify many well-established T cell subsets, even when surface protein data from CITE-seq is integrated, reducing its utility for detailed immunophenotyping. |

| Sensitivity to Technical Noise [10] | The inherent sparsity and high noise levels in scRNA-seq data can lead to unstable clusters that reflect technical artifacts rather than true biology. |

| Dependence on Expert Knowledge [9] [11] | Manual annotation of clusters is labor-intensive, subjective, and can lead to inconsistent results across studies, especially when marker genes are expressed in multiple cell types. |

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental disconnect between the biological reality of T cell states and the output of traditional clustering methods.

Emerging Alternative Frameworks and Benchmarking Insights

Recognizing these limitations, the field has developed advanced computational strategies that move beyond simple clustering. These methods can be broadly categorized, and their performance has been evaluated in several benchmarking studies [9] [12].

Component-Based Models

Methods like consensus Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (cNMF) model a cell's transcriptome as an additive mixture of biologically interpretable gene expression programs (GEPs) [3]. This allows a single cell to be characterized by multiple functional states simultaneously, directly addressing the co-expression limitation of clustering. The recently developed T-CellAnnoTator (TCAT) pipeline and its generalized software package starCAT use this principle to provide a reproducible framework for T cell annotation [3].

Automated Cell Type Annotation Tools

These tools reduce manual effort and subjectivity. They can be classified into several strategic approaches [9]:

- Reference-Based/Label Transfer (e.g., Azimuth, SingleR): Maps query cells to a pre-annotated reference dataset.

- Gene Set-Based/Supervised Learning (e.g., CellTypist): Trains a classification model on well-annotated datasets.

- Marker Gene-Based/Semi-Supervised (e.g., Garnett, scGate): Uses hierarchical models of marker genes to classify cells.

Performance Comparison in Benchmarking Studies

Independent evaluations have compared the performance of these automated methods. One study on COVID-19 PBMC data found that cell-based methods (e.g., Azimuth, SingleR) could confidently annotate a much higher percentage of cells than cluster-based methods (e.g., SCSA, scCATCH) [12]. Another benchmark focused on 10x Xenium spatial transcriptomics data concluded that SingleR was a top-performing tool, being fast, accurate, and producing results that closely matched manual annotation [13].

A separate evaluation of ten R packages highlighted that while Seurat (which uses clustering) was effective for annotating major cell types, it had a major drawback: poor performance in predicting rare cell populations and differentiating between highly similar cell types [14].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Annotation Methods

To objectively compare the performance of traditional clustering against newer annotation methods, researchers employ rigorous benchmarking protocols. The workflow below outlines a standard methodology for such an evaluation, drawing from published benchmark studies [13] [12].

Key Experimental Steps:

Ground Truth Establishment: Benchmarking relies on a trusted reference for validation. This can be a:

Data Preprocessing: Consistent and rigorous quality control (QC) is applied to both reference and query datasets. This includes:

Method Application and Evaluation: Multiple annotation methods are run on the same processed query data. Performance is quantified by:

- Accuracy: The percentage of cells correctly annotated compared to the ground truth.

- Recall: The percentage of cells that receive a confident annotation [12].

- Sensitivity to Rare Cells: The method's ability to correctly identify small cell populations [14].

- Robustness: Performance consistency when challenged with down-sampled genes or increased noise [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Success in single-cell T cell research depends on a combination of wet-lab reagents and dry-lab computational tools. The following table details key resources for implementing advanced annotation workflows.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Context of Use |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Xenium [13] | Imaging-based spatial transcriptomics platform; profiles hundreds of genes at single-cell resolution. | Analyzing spatial context of T cells in tumor microenvironments or tissues. |

| CITE-seq [3] | Measures single-cell transcriptome and surface protein expression simultaneously. | Provides orthogonal protein-level validation for RNA-based T cell annotations (e.g., validating CD8+ T cells). |

| CellMarker/CancerSEA [10] [11] | Databases of curated cell-type-specific marker genes. | Used by marker-based tools (SCSA, scCATCH) and for manual validation of annotations. |

| starCAT/TCAT [3] | Software pipeline for reproducible annotation based on predefined gene expression programs (GEPs). | Quantifying complex T cell activation states (proliferation, cytotoxicity, exhaustion) across datasets. |

| SingleR [13] [14] [12] | Reference-based cell type annotation tool using correlation analysis. | Fast and accurate annotation of PBMC or tissue-derived T cells against existing atlases. |

| Azimuth [13] [12] | Reference-based annotation method integrated into the Seurat ecosystem. | Projecting and annotating query datasets onto a pre-built, annotated reference UMAP. |

| Harmony [3] | Batch effect correction algorithm. | Integrating multiple scRNA-seq datasets to learn robust, dataset-invariant GEPs for tools like TCAT. |

The evidence is clear: traditional clustering methods, while foundational, possess critical limitations for annotating the complex and continuous spectrum of T cell states. They force a discrete structure on continuous biology, fail to resolve co-expressed gene programs, and struggle with rare populations. Benchmarking studies consistently show that newer, specialized computational methods—including reference-based tools like SingleR and Azimuth, and component-based models like starCAT/TCAT—offer superior accuracy, robustness, and resolution [3] [13] [12].

The future of T cell annotation lies in the continued development and adoption of these sophisticated frameworks. Emerging trends include the use of large language models to improve annotation accuracy and scalability, and the integration of isoform-level transcriptomic data from long-read sequencing to achieve even higher resolution in cell type definition [15]. For researchers and drug developers, moving beyond traditional clustering is no longer an option but a necessity to fully unravel T cell heterogeneity and its role in health and disease.

Key Technological Advances Enabling High-Resolution T Cell Profiling

High-resolution profiling of T cells is revolutionizing our understanding of immune responses in cancer, autoimmune diseases, and therapeutic interventions. By moving beyond traditional, discrete classifications, new technologies are revealing a continuum of T cell states and enabling the precise engineering of next-generation therapies. This guide objectively compares the performance of key technological advances—spanning spatial transcriptomics, computational annotation, functional screening, and morphological profiling—that are setting new benchmarks in single-cell T cell research.

Spatial Transcriptomics: Mapping Cellular Neighborhoods

Spatial transcriptomics technologies have bridged a critical gap in single-cell analysis by preserving the spatial context of cells within a tissue, which is crucial for understanding mechanisms like immune surveillance and tumor evasion.

Visium HD from 10x Genomics represents a significant leap forward, offering whole-transcriptome analysis at a 2-µm resolution, which approaches single-cell scale. When benchmarked against its predecessor, Visium v2 (with 55-µm resolution), Visium HD demonstrates superior performance in mapping the tumor immune microenvironment. A study profiling human colorectal cancer (CRC) samples showed that Visium HD's increased resolution allowed for the precise identification and localization of transcriptomically distinct macrophage subpopulations and a clonally expanded T cell population within different tumor niches [16]. The technology's high spatial accuracy was quantified by localizing known glandular marker genes, with 98.3–99% of transcripts found in their expected morphological structures [16].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Spatial Transcriptomic Technologies

| Technology | Resolution | Tissue Compatibility | Key Application in T Cell Profiling | Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visium HD (10x Genomics) | 2-µm bins (single-cell scale) | FFPE, Fresh Frozen | Mapping immune cell niches and clonally expanded T cells in colorectal cancer [16]. | Spatial accuracy of 98.3-99% for expected transcript localization [16]. |

| Xenium In Situ (10x Genomics) | Subcellular | FFPE | Independent validation of macrophage and T cell localizations identified by Visium HD [16]. | High spatial accuracy for targeted gene panels. |

| Visium v2 (10x Genomics) | 55-µm spots | FFPE, Fresh Frozen | Serves as a benchmark; lower resolution limits precise cellular mapping [16]. | ~5,000 capture areas per slide [16]. |

Experimental Protocol for Spatial Transcriptomics

The typical workflow for a Visium HD experiment on FFPE tissue sections, as described by [16], involves:

- Tissue Preparation: Sectioning FFPE tissue blocks to a specified thickness (e.g., 5 µm).

- Probe Ligation: Target probes are hybridized to the tissue's mRNA and subsequently ligated.

- Capture with CytAssist: The CytAssist instrument is used to transfer the ligated probes from the tissue onto the Visium HD slide, which contains a continuous lawn of capture oligonucleotides, thereby preserving spatial information.

- Library Construction & Sequencing: The captured probes are used to construct sequencing libraries.

- Data Analysis: The Space Ranger pipeline processes the raw data, outputting it at 2-µm, 8-µm, and 16-µm bin resolutions. Data is then typically deconvolved using a single-cell reference atlas to annotate cell types.

Workflow for Visium HD Spatial Profiling

Computational Annotation: Deciphering T Cell Continuous States

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revealed that T cell states exist on a continuum, challenging traditional clustering-based analysis. Component-based computational models have emerged to address this complexity.

The T-CellAnnoTator (TCAT) / starCAT pipeline uses consensus nonnegative matrix factorization (cNMF) to define a fixed catalog of 46 reproducible gene expression programs (cGEPs) from 1.7 million T cells across 38 human tissues and five disease contexts [3] [4]. When benchmarked against de novo cNMF analysis, starCAT demonstrated superior performance, especially for small query datasets. In simulations, it accurately inferred the usage of GEPs overlapping with the reference (Pearson R > 0.7) and maintained consistent performance even when the query dataset contained as few as 100 cells, whereas the performance of de novo cNMF declined significantly [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Single-Cell Annotation Methods for T Cells

| Method | Core Approach | Key Advantage | Performance in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCAT/starCAT | Predefined catalog of 46 cGEPs using cNMF. | Models continuous, co-expressed states; enables cross-dataset comparison. | Pearson R > 0.7 for GEP usage inference; outperforms de novo cNMF on small queries [3] [4]. |

| De novo cNMF | Discovers GEPs anew for each dataset. | Does not require a predefined reference. | Performance declines with smaller dataset size (<20,000 cells) [4]. |

| Hard Clustering (e.g., Seurat) | Discretizes cells into distinct clusters. | Widely adopted and user-friendly. | Fails to resolve co-expressed GEPs and continuous state transitions [3]. |

| scTissueID | Machine learning with cell quality filtering. | High accuracy in cell and tissue type identification. | Outperformed 8 other annotation pipelines and 6 ML algorithms in a comparative study [17]. |

Experimental Protocol for Computational Annotation with starCAT

The workflow for applying the starCAT pipeline, as detailed in [3] [4], involves two major phases:

- Reference Catalog Construction:

- Data Collection: Aggregate multiple large-scale scRNA-seq datasets (e.g., from blood and various tissues).

- Batch Correction: Apply modified Harmony integration to gene-level data to remove technical artifacts while preserving non-negativity.

- GEP Discovery: Run cNMF on each batch-corrected dataset to identify gene expression programs.

- Consensus GEP Definition: Cluster highly correlated GEPs from different datasets to create a robust, multi-dataset catalog of consensus GEPs (cGEPs).

- Query Dataset Annotation:

- GEP Usage Inference: For a new query dataset, use non-negative least squares (NNLS) regression to score the activity (usage) of each predefined cGEP in every cell.

- Cell State Prediction: Leverage the GEP usages to predict functional features like T cell activation and exhaustion.

Functional Profiling: From Genetics to Morphology

Understanding T cell function extends beyond transcriptomics to include genetic determinants of efficacy and real-time functional responses.

CRISPR Screening for Enhanced T Cell Therapies

The CELLFIE platform is a CRISPR screening platform designed to discover gene knockouts that enhance the fitness and efficacy of primary human CAR T cells. In a genome-wide knockout screen, CAR T cells were stimulated via their CAR (using CD19+ K562 cells) or their endogenous TCR, with readouts for proliferation, fratricide, and exhaustion markers [18]. The platform achieved high-quality data, with stronger depletion of essential genes than some prior T cell screens. Key discoveries included RHOG and FAS knockouts, which were validated as potent enhancers of CAR T cell anti-tumor activity in xenograft models, both individually and synergistically as a double knockout [18].

High-Content Imaging for Morphological Profiling

A High-Content Cell Imaging (HCI) pipeline was developed to predict clinical response to natalizumab in multiple sclerosis patients by profiling the in vitro sensitivity of T cells to the drug. The method involved [19]:

- Stimulation & Staining: PBMCs from patients were exposed to natalizumab or a control and seeded onto VCAM-1-coated plates. Cells were stained for CD4/CD8, F-actin, and phosphorylated SLP76 (pSLP76).

- Automated Imaging: Confocal imaging with a 40x objective was performed on the basal plane of adherent cells.

- Feature Extraction: Metrics like cell area, width-to-length ratio, and F-actin/pSLP76 intensity were extracted. Unsupervised clustering of these morphological features from CD8+ T cells partially discriminated non-responder patients. Furthermore, a random forest model trained on these features predicted treatment response with 92% accuracy in a discovery cohort and 88% in a validation cohort [19].

Research Reagent Solutions for T Cell Profiling

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Advanced T Cell Profiling

| Research Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| CROP-seq-CAR Vector | Co-delivers CAR and gRNA via single lentivirus. | Enables pooled CRISPR screens in primary CAR T cells [18]. |

| MHC Class I Tetramers / Anti-CD137 | Identifies antigen-specific T cells. | Used with spectral flow cytometry for metabolic profiling of virus/tumor-specific CD8+ T cells [20]. |

| Visium HD Spatial Gene Expression Slide | Captures whole-transcriptome data with spatial context. | Mapping immune cell niches in colorectal cancer FFPE samples [16]. |

| LEVA (Light-induced EVP adsorption) | Patterns extracellular vesicles and particles with UV light. | Studying neutrophil swarming behavior in response to patterned bacterial EVPs [21]. |

The benchmarking of these advanced technologies reveals a clear trajectory in T cell profiling: each excels in a specific dimension. Visium HD provides unparalleled spatial context, TCAT/starCAT offers a reproducible framework for deciphering continuous transcriptional states, CELLFIE enables the systematic functional discovery of genetic enhancers for therapy, and HCI bridges in vitro assays with clinical response predictions. Together, they provide a powerful, multi-faceted toolkit for researchers and drug developers to decode T cell biology with unprecedented resolution and rigor, paving the way for more effective and personalized immunotherapies.

In the field of immunology, particularly in the study of T cell subsets, precise cell annotation is a critical prerequisite for understanding cellular heterogeneity, activation states, and functional programs. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revealed that T cells exist along a continuum of states rather than in clearly distinct subsets, necessitating advanced computational frameworks for accurate characterization [3]. Traditional clustering approaches often discretize this continuous variation, obscuring co-expressed gene expression programs (GEPs) and limiting our understanding of T cell biology. The computational methods developed to address these challenges fall into three major paradigms: supervised, unsupervised, and semi-supervised learning, each with distinct strengths for specific research scenarios.

This guide provides an objective comparison of these annotation approaches within the context of benchmarking studies for T cell research, offering experimental data and methodological details to help researchers and drug development professionals select appropriate tools for their specific applications.

Methodological Foundations and Definitions

Core Computational Paradigms

Supervised learning represents a machine learning approach where algorithms are trained on labeled data, meaning each input data point is paired with a corresponding output label [22]. In the context of single-cell annotation, researchers use a reference dataset with pre-annotated cell types to train a model that can then predict cell types in new, unlabeled query datasets [10]. This approach requires high-quality, well-annotated reference data but typically yields highly accurate and reproducible annotations when such references are available.

Unsupervised learning encompasses methods that identify patterns and structures in unlabeled data without pre-existing annotations or training [23]. These techniques are particularly valuable for exploratory analysis where reference datasets may be incomplete or when discovering novel cell states. Common unsupervised approaches include clustering algorithms that group cells based on similarity metrics and dimensionality reduction methods that help visualize high-dimensional single-cell data [24].

Semi-supervised learning occupies a middle ground, leveraging both labeled and unlabeled data to improve annotation accuracy, particularly when fully labeled reference datasets are limited or costly to produce [22]. This approach can enhance model generalization by using the underlying structure of unlabeled data to inform decisions about cellular identities, making it particularly useful for rare cell type identification or when working with emerging technologies where comprehensive references are not yet established.

Technical Implementation in Single-Cell Research

In practical single-cell research, these paradigms manifest as specific computational tools and pipelines. For T cell studies, the recently developed T-CellAnnoTator (TCAT) pipeline utilizes a component-based model that simultaneously quantifies predefined gene expression programs capturing activation states and cellular subsets [3]. This approach improves upon traditional clustering by modeling transcriptomes as weighted mixtures of GEPs, enabling more nuanced characterization of T cell states.

Reference-based annotation methods like SingleR, Azimuth, and scMap employ correlation-based matching between query cells and reference profiles, while data-driven methods train classification models on pre-labeled cell type datasets [10]. The emergence of deep learning approaches has further expanded the toolkit, with methods like STAMapper using heterogeneous graph neural networks to transfer cell-type labels from scRNA-seq data to spatial transcriptomics data [25].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Annotation Approaches

| Characteristic | Supervised Learning | Unsupervised Learning | Semi-Supervised Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input Data | Labeled reference datasets | Unlabeled data only | Mix of labeled and unlabeled data |

| Human Intervention | Required for labeling | Limited to interpretation | Moderate for validation |

| Primary Use | Predicting known cell types | Discovering novel patterns | Improving learning with limited labels |

| Computational Complexity | Generally simpler | More complex | Variable, often moderate |

| Accuracy on Known Types | Higher | Lesser | Can approach supervised performance |

| Novel Cell Type Discovery | Limited | Excellent | Moderate with proper implementation |

Benchmarking Performance in Single-Cell Research

Experimental Frameworks for Method Evaluation

Rigorous benchmarking studies have established standardized protocols for evaluating annotation methods. A comprehensive assessment of reference-based annotation tools for 10x Xenium spatial transcriptomics data utilized paired single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) data as a reference to minimize variability between reference and query datasets [13]. This approach enabled direct comparison of method performance against manual annotation based on established marker genes.

In large-scale T cell studies, researchers have analyzed over 1.7 million T cells from 700 individuals across 38 tissues and five disease contexts to identify 46 reproducible gene expression programs reflecting core T cell functions [3]. The reproducibility of these GEPs was quantified by clustering them across datasets, with consensus GEPs (cGEPs) defined as averages of each cluster. This massive dataset provides a robust foundation for benchmarking annotation methods.

Performance metrics commonly used in these evaluations include:

- Accuracy: The proportion of correctly annotated cells overall

- Macro F1 Score: The unweighted mean of per-class F1 scores, important for rare cell types

- Weighted F1 Score: The mean of per-class F1 scores weighted by support

- Cross-dataset Concordance: Measurement of how well GEPs reproduce across different studies

Comparative Performance Data

Recent benchmarking studies provide quantitative comparisons of annotation methods. In spatial transcriptomics annotation, STAMapper demonstrated significantly higher accuracy compared to competing methods (scANVI, RCTD, and Tangram) across 81 single-cell spatial transcriptomics datasets [25]. The method maintained superior performance even under conditions of poor sequencing quality, particularly for datasets with fewer than 200 genes where it achieved median accuracy of 51.6% compared to 34.4% for the second-best method at a down-sampling rate of 0.2.

For 10x Xenium data, a systematic evaluation of five reference-based methods (SingleR, Azimuth, RCTD, scPred, and scmapCell) against manual annotation found that SingleR performed best, being fast, accurate, and easy to use, with results closely matching manual annotation [13].

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance of Annotation Methods Across Technologies

| Method | Type | Reported Accuracy | Best Use Context | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCAT | Unsupervised | Identified 46 reproducible GEPs | Large-scale T cell analysis across tissues | Requires large datasets for optimal performance |

| STAMapper | Supervised | Significantly outperformed competitors (p = 1.3e-27 to 2.2e-14) | Spatial transcriptomics with limited genes | Complex implementation for non-specialists |

| SingleR | Supervised | Closest match to manual annotation | 10x Xenium data with snRNA-seq reference | Performance depends on reference quality |

| cNMF/starCAT | Unsupervised | High cross-dataset reproducibility (mean R = 0.74-0.81) | Identifying co-expressed gene programs | May miss rare populations in small datasets |

| Semi-supervised | Semi-supervised | Improved accuracy with limited labels | Medical imaging with few expert annotations | Less accurate than supervised with full labels |

Experimental Protocols for Annotation Benchmarking

Reference-Based Annotation Workflow

A standardized protocol for benchmarking reference-based annotation methods involves several key steps [13]:

Reference Preparation: High-quality single-cell or single-nucleus RNA sequencing data is processed using standard pipelines (e.g., Seurat). Quality control includes removing cells without validated annotations, normalizing data, selecting highly variable genes, and performing dimensionality reduction.

Query Data Processing: Spatial transcriptomics data undergoes similar quality control, with adjustments for technology-specific limitations (e.g., using all genes for Xenium data due to small panel size).

Method Implementation: Each annotation tool is applied using the prepared reference:

- SingleR: Uses correlation between reference and query datasets

- Azimuth: Requires special reference preparation with SCTransform normalization

- RCTD: Employs a regression framework accounting for platform effects

- scPred: Trains a model on the reference before predicting query cell types

- scmapCell: Creates a cell index before projection and cluster assignment

Performance Validation: Predictions are compared against manual annotations based on marker genes, with metrics calculated for accuracy and cell type-specific performance.

Unsupervised GEP Discovery Pipeline

For unsupervised discovery of gene expression programs in T cells, the TCAT pipeline employs these key experimental steps [3]:

Data Integration and Batch Correction: Multiple scRNA-seq datasets are integrated using modified Harmony algorithms to correct batch effects while maintaining non-negative values compatible with nonnegative matrix factorization.

Consensus Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (cNMF):

- Repeated NMF runs are performed to mitigate randomness

- Outputs are combined into robust estimates of GEP spectra (gene weights)

- Per-cell activities ("usages") are calculated reflecting relative GEP contributions

Cross-Dataset GEP Alignment:

- GEPs from different datasets are clustered based on similarity

- Consensus GEPs (cGEPs) are defined as cluster averages

- Reproducibility is quantified by measuring how many GEPs cluster across datasets

Biological Validation:

- cGEPs are annotated by examining top-weighted genes

- Association with surface marker-based gating is assessed via multivariate logistic regression

- Gene-set enrichment analysis provides functional annotations

Single-Cell Annotation Workflow Selection

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for Single-Cell Annotation

| Resource | Type | Function in Annotation | Applicable Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Xenium | Platform | Provides imaging-based spatial transcriptomics data | Cellular-level spatial gene expression profiling |

| CITE-seq Data | Data Type | Enhances GEP interpretability with surface protein measurements | Multimodal cell state characterization |

| CellMarker/PanglaoDB | Database | Provides known marker genes for cell type identification | Manual annotation and method validation |

| Seurat | Software Toolkit | Standard pipeline for scRNA-seq data analysis | Data preprocessing, normalization, and clustering |

| Harmony | Algorithm | Corrects batch effects in integrated datasets | Multi-dataset analysis and reference construction |

| TCAT/starCAT | Pipeline | Quantifies predefined gene expression programs | T cell subset and activation state characterization |

| STAMapper | Tool | Transfers labels from scRNA-seq to spatial data | Single-cell spatial transcriptomics annotation |

| SingleR | Method | Fast correlation-based cell type prediction | Reference-based annotation with scRNA-seq data |

The benchmarking data presented in this guide demonstrates that each major category of annotation approaches—supervised, unsupervised, and semi-supervised—has distinct advantages depending on the research context. For well-established cell types with available reference data, supervised methods like SingleR and STAMapper provide high accuracy and computational efficiency. For discovering novel cell states or when reference data is limited, unsupervised approaches like cNMF offer superior ability to identify biologically meaningful patterns without prior annotations.

In T cell research specifically, the continuum of activation states and the complex interplay of gene expression programs necessitates methods that can capture this complexity without imposing artificial discretization. The development of pipelines like TCAT and starCAT represents significant advances in this direction, enabling reproducible annotation across datasets and biological contexts.

As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, particularly in spatial transcriptomics and multi-omics integration, the field will likely see increased adoption of semi-supervised approaches that leverage limited expert knowledge while exploring the full complexity of cellular heterogeneity. Researchers should select annotation methods based on their specific biological questions, data characteristics, and the availability of validated reference data, using the benchmarking frameworks outlined here to validate their choices.

The Critical Role of Reference Databases and Atlas Projects

In the field of immunology, particularly in the study of T cells, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revealed a previously underestimated continuum of cellular states, moving beyond the traditional, discrete subsets like Th1, Th2, and Th17 [3] [4]. This complexity presents a major challenge: how can researchers consistently identify and compare T cell states across different studies, laboratories, and disease conditions? The answer lies in standardized reference databases and cell atlas projects. These resources provide a stable biological coordinate system, enabling reproducible annotation of scRNA-seq data and accelerating discoveries in cancer, autoimmunity, and infectious diseases [26] [27]. This guide benchmarks the performance of leading atlas-based annotation tools, providing experimental data and protocols to guide researchers in selecting the optimal method for their studies.

Comparative Performance of T Cell Annotation Tools

Table 1: Benchmarking of Major T Cell Reference Atlas and Annotation Tools

| Tool Name | Core Methodology | Reference Scale & Context | Demonstrated Annotation Accuracy | Key Strengwarts | Identified Cell States/Programs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCAT/starCAT [3] [4] | Consensus Non-negative Matrix Factorization (cNMF) & projection | 1.7 million T cells; 700 individuals; 38 tissues; 5 diseases (COVID-19, cancer, RA) [3] | >0.7 Pearson R for GEP usage in simulations; outperforms de novo cNMF in small queries [4] | Quantifies co-expressed gene programs; captures continuous states; fast projection with NNLS [3] | 46 reproducible consensus Gene Expression Programs (cGEPs) for subsets, exhaustion, cytotoxicity [3] |

| ProjecTILs [27] [28] | Reference atlas projection via batch-corrected integration | ~16,800 murine T cells; 25 samples; melanoma & colon cancer models [27] | Accurate embedding and label transfer; characterizes states deviating from reference [27] | Preserves reference structure; allows discovery of "deviant" states; interactive atlases [27] [28] | 9 broad functional clusters (e.g., Tpex, Tex, Th1-like, Tfh, Treg) [27] |

| STCAT [29] | Hierarchical models & marker correction | 1.35 million human T cells; 35 conditions; 16 tissues [29] | 28% higher accuracy vs. existing tools on 6 independent datasets [29] | Automated hierarchical annotation; integrated TCellAtlas database for browsing & analysis [29] | 33 subtypes classified into 68 categories by subtype and state [29] |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Atlas Tools

The performance data presented in Table 1 are derived from rigorous experimental and computational benchmarks. Below are summaries of the key methodologies used to generate this validation data.

Simulation-Based Benchmarking of starCAT

- Objective: To evaluate the accuracy of transferring gene expression program (GEP) annotations from a large reference to a smaller query dataset, especially when their cellular compositions do not perfectly overlap [4].

- Protocol:

- Data Simulation: Two large reference datasets (100,000 cells each) and a smaller query dataset (20,000 cells) were simulated. Each cell was programmed to express a combination of "subset-defining" and "non-subset" GEPs.

- Introduction of Variance: The references were designed to either contain extra GEPs not present in the query or lack certain GEPs that were in the query. Only 90% of genes were shared between reference and query to mimic real-world conditions [4].

- Analysis & Metric: GEPs were learned from the references using cNMF. starCAT was then used to project these reference GEPs onto the query dataset. Accuracy was quantified by the Pearson correlation (R) between the projected GEP usage values and the known ground-truth values from the simulation [4].

- Outcome: starCAT robustly inferred the usage of overlapping GEPs (R > 0.7) and correctly assigned low usage to non-overlapping GEPs. Notably, it outperformed running cNMF de novo on the smaller query dataset, demonstrating the advantage of leveraging a large, fixed reference [4].

Cross-Study Integration and Validation of ProjecTILs

- Objective: To construct a robust, batch-effect-corrected reference atlas of tumor-infiltrating T cell (TIL) states from multiple independent studies and validate its utility for projecting new data [27].

- Protocol:

- Atlas Construction: scRNA-seq data from 21 murine tumors and 4 tumor-draining lymph nodes were collected from public sources and new experiments. The STACAS algorithm was used to integrate these datasets, correcting for technical batch effects while preserving biological variation [27].

- Annotation: Unsupervised clustering and gene enrichment analysis, supported by a supervised classifier (TILPRED), were used to annotate functional clusters in the integrated map (e.g., Tpex, Tex, Tfh) [27].

- Projection Validation: New query datasets were projected into the reference space. The method's accuracy was assessed by its ability to correctly place cells from known subtypes into their corresponding annotated areas of the reference atlas and to identify novel states not originally in the reference [27].

- Outcome: The resulting atlas provided a unified system of coordinates that summarized TIL diversity into distinct, biologically validated functional clusters. ProjecTILs successfully mapped new data into this stable reference, enabling direct cross-condition and cross-study comparisons [27].

Independent Dataset Validation of STCAT

- Objective: To assess the real-world annotation accuracy of STCAT against other tools on independently generated scRNA-seq datasets [29].

- Protocol:

- Reference Building: A large human T cell reference (TCellAtlas) was constructed from over 1.3 million cells across diverse conditions and tissues.

- Tool Comparison: STCAT and other existing annotation tools were applied to six independent validation datasets, including both cancer and healthy samples.

- Accuracy Measurement: The tool's predictions were compared against manually curated, expert-based annotations considered to be the "ground truth." Accuracy was calculated as the percentage of correctly labeled cells across all major T cell subtypes [29].

- Outcome: STCAT achieved a 28% higher accuracy in annotating T cell subtypes compared to other tools on these independent datasets, validating its hierarchical model and marker correction approach [29].

Workflow Diagram: From Single-Cell Data to Annotated Atlas

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for constructing a reference atlas and using it to annotate query datasets, integrating key steps from tools like TCAT and ProjecTILs.

Table 2: Key Databases and Computational Tools for T Cell Atlas Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCellAtlas [29] | Transcriptomics Reference Database | Repository for T cell scRNA-seq profiles and annotations. | Serves as a standardized reference for automated annotation of human T cell subtypes and states using STCAT. |

| TCRdb [30] | TCR Sequence Database | Aggregates TCR sequences with metadata (antigen specificity, disease context). | Analyzing T cell repertoire diversity, clonal expansion, and antigen-specific responses across conditions. |

| VDJdb [30] | TCR Sequence Database | Curated repository of TCR sequences with known antigen specificity. | Identifying and studying antigen-specific T cells, crucial for vaccine and cancer immunotherapy development. |

| scGate [9] | Computational Tool | Marker-based automated cell purification using a hierarchical gating strategy. | Isolating pure populations of specific cell types from heterogeneous scRNA-seq data prior to deeper analysis. |

| CellTypist [9] | Computational Tool | Automated cell type annotation using a model trained on reference atlases. | Rapid, standardized annotation of immune cells in large-scale scRNA-seq datasets. |

The benchmarking data clearly demonstrates that atlas-based annotation methods—TCAT/starCAT, ProjecTILs, and STCAT—provide a superior framework for the reproducible interpretation of T cell states compared to unsupervised analysis of individual datasets. Their ability to quantify complex, co-expressed gene programs [3], project new data into a stable reference space [27], and deliver higher annotation accuracy [29] makes them indispensable. The consistent finding of enriched Tregs in tumors and specific T helper states in disease stages across multiple studies and tools underscores the power of this approach. As these reference atlases and databases continue to expand in scale and diversity, they will form the foundational infrastructure for a new era of precision immunology, ultimately accelerating the development of novel diagnostics and immunotherapies.

Practical Implementation of T Cell Annotation Tools and Pipelines

Component-based models have emerged as powerful computational frameworks for analyzing single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data, addressing critical limitations of traditional clustering approaches. Unlike hard clustering methods that force cells into discrete, mutually exclusive groups, component-based models represent each cell's transcriptome as a weighted combination of gene expression programs (GEPs) [3]. This approach is particularly valuable for analyzing complex biological systems where cells exist along continuous phenotypic spectra and simultaneously execute multiple biological programs, as commonly observed in T cell biology [4].

These models mathematically decompose the high-dimensional gene expression matrix into two lower-dimensional matrices: a program matrix containing the defining genes for each GEP, and a usage matrix quantifying the activity of each program in every cell [31]. This formulation enables researchers to dissect the complex interplay between cell identity programs (defining cell types) and cell activity programs (reflecting dynamic processes like activation, exhaustion, or metabolic states) [31]. Within this landscape, methods based on non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) have gained prominence due to their ability to produce interpretable, parts-based representations that align well with biological intuition [32] [33].

This review comprehensively benchmarks two prominent approaches in this domain: traditional NMF-based methods and the recently developed TCAT/starCAT framework. We evaluate their performance in identifying and annotating T cell subsets, activation states, and functions, with particular emphasis on experimental validation, reproducibility, and applicability to translational research.

Methodological Frameworks and Algorithms

Non-Negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) Foundations

Non-negative matrix factorization is a family of algorithms that decompose a non-negative data matrix A (n genes × m cells) into two non-negative factor matrices: W (n genes × k programs) and H (k programs × m cells), such that A ≈ W × H [32]. The non-negativity constraint fosters interpretability as biological concepts like gene expression cannot be negative. Each column of W represents a metagene or GEP, defined by its constituent genes and their weights, while each column of H specifies how active these programs are in a given cell [32] [33].

Several NMF variants have been developed for biological applications. Consensus NMF (cNMF) addresses the instability of standard NMF by running multiple iterations with different initializations, filtering outlier components, and clustering results to produce robust consensus programs [31]. Nonnegative spatial factorization (NSF) extends NMF to spatial transcriptomics by incorporating Gaussian process priors that capture spatial correlation structure [33]. The NSF hybrid (NSFH) model further partitions variability into both spatial and nonspatial components, enabling quantification of spatial importance for genes and observations [33].

The TCAT/starCAT Framework

T-CellAnnoTator (TCAT) and its generalized counterpart starCAT represent a specialized pipeline for GEP-based annotation that builds upon but meaningfully extends traditional NMF approaches [3] [34]. The framework operates in two primary phases: GEP discovery and GEP annotation.

The discovery phase applies consensus NMF to multiple reference datasets while incorporating specific enhancements to improve cross-dataset reproducibility [3]. To address batch effects that typically confound cross-dataset analysis, TCAT adapts Harmony integration to provide batch-corrected nonnegative gene-level data, which is essential for matrix factorization [3]. For CITE-seq datasets, it further incorporates surface protein measurements into GEP spectra to enhance biological interpretability [3].

The annotation phase enables the transfer of learned GEPs to new query datasets using non-negative least squares (NNLS) regression to quantify the usage of predefined GEPs in each cell [3] [4]. This approach provides a consistent coordinate system for comparing cellular states across datasets, biological contexts, and experimental conditions, addressing a key limitation of de novo analysis methods.

Spectra: A Supervised Alternative

Spectra represents another recent advancement in component-based modeling that incorporates prior biological knowledge through gene-gene knowledge graphs [35]. Unlike purely unsupervised methods, Spectra uses existing gene sets and cell-type labels as input, explicitly models cell-type-specific factors, and represents input gene sets as a graph structure that guides the factorization [35]. This supervised approach allows Spectra to balance prior knowledge with data-driven discovery, detecting novel programs from residual unexplained variation while maintaining interpretability through graph-based regularization.

Experimental Benchmarking and Performance Comparison

Benchmarking Design and Metrics

Rigorous benchmarking of computational methods requires carefully designed experiments that evaluate performance across multiple dimensions. For component-based models, key evaluation criteria include: accuracy in recovering known biological signals, reproducibility across datasets and experimental conditions, interpretability of discovered programs, computational efficiency, and robustness to noise and batch effects [36] [3].

The single-cell integration benchmarking (scIB) framework provides quantitative metrics for assessing integration performance, focusing on both batch correction and biological conservation [36]. However, recent research has revealed limitations in these metrics for fully capturing intra-cell-type biological variation, leading to proposed enhancements in the scIB-E framework that better account for fine-grained biological structure preservation [36].

Performance Comparison Across Methods

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Component-Based Models in T Cell Applications

| Method | GEP Reproducibility | Cross-Dataset Transfer | Runtime Efficiency | Biological Interpretability | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCAT/starCAT | High (9 cGEPs across 7 datasets) [3] | Excellent (NNLS projection) [3] | Fast annotation phase [3] | High (46 curated cGEPs) [3] | Fixed GEP catalog enables consistent cross-dataset comparison |

| cNMF | Moderate (requires consensus approach) [31] | Limited (requires de novo analysis) | Moderate (requires multiple runs) [31] | Moderate to high [31] | Does not require pre-specified gene sets |

| Spectra | High (graph-guided factorization) [35] | Good (fixed factor representation) | Moderate (depends on graph size) [35] | High (incorporates prior knowledge) [35] | Balances prior knowledge with novel discovery |

| NMF (standard) | Low (high variability between runs) [31] | Poor | Fast (single run) | Variable (often mixed programs) [31] | Simple implementation |

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarking Results from Experimental Studies

| Benchmark Scenario | TCAT/starCAT Performance | Alternative Method Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEP Transfer Accuracy | Pearson R > 0.7 for overlapping GEPs [3] | cNMF performance declines in small queries [3] | Simulation with partially overlapping GEPs between reference and query [3] |

| Factorization Interpretability | 171/197 factors strongly constrained by biological graph (η ≥ 0.25) [35] | NMF and scHPF factors show poor agreement with annotated gene sets [35] | Application to breast cancer scRNA-seq data [35] |

| Cell-Type Specificity | Accurate restriction of CD8+ T cell programs to appropriate lineage [35] | ExpiMap and Slalom misassign TCR activity to myeloid/NK cells [35] | Analysis of tumor immune contexts [35] |

| Program Reproducibility | 46 consensus GEPs from 1.7M cells across 38 tissues [3] | PCA components show substantially less concordance across datasets [3] | Integration of 7 scRNA-seq datasets [3] |

Case Study: T Cell Atlas Integration

A landmark application of TCAT involved the integration of 1.7 million T cells from 700 individuals across 38 tissues and five disease contexts [3] [4]. This analysis identified 46 reproducible consensus GEPs (cGEPs) representing core T cell functions including proliferation, cytotoxicity, exhaustion, and effector states [3]. Notably, 9 cGEPs were consistently identified across all seven analyzed datasets, demonstrating exceptional reproducibility, while 49 cGEPs were found in two or more datasets [3].

When benchmarking cross-dataset transfer performance, TCAT significantly outperformed de novo cNMF analysis, particularly for small query datasets [3] [4]. This advantage stems from TCAT's ability to leverage large reference datasets for robust GEP discovery while efficiently projecting these programs onto query data using NNLS, unlike cNMF which must rediscover programs from limited data [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

TCAT/starCAT Workflow Implementation

The standard TCAT workflow consists of two sequential phases with distinct computational procedures:

Phase 1: Reference GEP Discovery

- Data Collection and Curation: Gather scRNA-seq datasets with appropriate cell-type annotations and experimental metadata [3].

- Batch Effect Correction: Apply modified Harmony integration to generate batch-corrected, nonnegative gene-level data compatible with NMF [3].

- Consensus NMF: Run cNMF with multiple initializations (typically 100-200 runs) and aggregate results to mitigate random initialization effects [3] [31].

- GEP Clustering and Consensus Building: Cluster highly correlated GEPs from different datasets and define cGEPs as cluster averages [3].

- Biological Annotation: Curate cGEPs through examination of top-weighted genes, gene-set enrichment analysis, and association with surface protein markers in CITE-seq data [3].

Phase 2: Query Dataset Annotation

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize query data using consistent methodology to reference datasets.

- GEP Usage Quantification: Apply non-negative least squares regression to estimate the activity of each reference cGEP in query cells [3].

- Cell State Prediction: Leverage GEP usages to predict additional cell features including lineage, TCR activation status, and cell cycle phase [3].

- Quality Control: Identify potential doublets or low-quality cells through aberrant GEP usage patterns [3].

GEP Discovery and Annotation Workflow in TCAT/starCAT

Validation Experiments and Statistical Analyses

Comprehensive validation is essential for establishing method reliability. Key experimental approaches include:

Simulation Studies: Benchmarking against ground truth data with known GEP structure provides quantitative performance assessment [3] [31]. Standard simulations involve generating synthetic scRNA-seq data where cells express specific combinations of predefined GEPs, then evaluating method accuracy in recovering these programs [3].

Cross-Validation: Splitting data into training and test sets, or using leave-one-dataset-out designs, assesses generalizability and robustness to batch effects [3].

Biological Validation: Experimental confirmation through complementary assays (CITE-seq, flow cytometry) or functional studies establishes biological relevance [3] [35]. For example, TCAT validation included association of cGEPs with surface protein markers in independent CITE-seq data [3].

Signaling Pathways and Biological Mechanisms

Key T Cell Signaling Pathways Identified Through Component-Based Models

Component-based models have elucidated complex signaling networks underlying T cell function and differentiation. The application of TCAT to 1.7 million T cells revealed 46 consensus GEPs encompassing diverse biological processes [3]:

T Cell Activation Programs: These include canonical TCR signaling, costimulatory pathways, and downstream effector programs. Spectra analysis successfully disentangled the highly correlated features of CD8+ T cell tumor reactivity and exhaustion, which are typically confounded in conventional analyses [35].

Cytokine and Helper T Cell Programs: TCAT identified specific GEPs for TH1, TH2, and TH17 responses, marked by characteristic transcription factors (TBX21, GATA3, RORC) and cytokines (IFNγ, IL-4/IL-5, IL-17/IL-26) [3]. Importantly, these programs were not mutually exclusive, with individual cells frequently co-expressing multiple helper program components.

Metabolic and Housekeeping Programs: Component-based models consistently identify metabolic pathways (oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis) and cellular maintenance processes as shared activity programs across multiple cell types [35] [31].

Novel Activation States: Beyond canonical programs, these methods have discovered previously uncharacterized T cell states, including a T peripheral helper (TPH) GEP in rheumatoid arthritis characterized by PD-1, LAG3, and CXCL13 expression [3].

T Cell Signaling Pathways Identified by Component-Based Models

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Implementing Component-Based Models

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Databases | Application in Workflow | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Frameworks | starCAT [3], Spectra [35], cNMF [31], NSF [33] | GEP discovery and annotation | Specialized algorithms for biological data |

| Data Resources | Human Lung Cell Atlas [36], Mouse Cell Atlas [37], Tabula Muris Senis [37] | Reference datasets for benchmarking | Annotated single-cell datasets across tissues |

| Gene Set Collections | Immunology knowledge base (231 gene sets) [35], MSigDB, GO Biological Process | Prior knowledge incorporation | Curated gene programs for supervised analysis |

| Benchmarking Tools | scIB/scIB-E metrics [36], simulation frameworks | Method validation and comparison | Quantitative performance assessment |

| Visualization Platforms | Scanpy [35], UMAP [36] | Result interpretation and exploration | Dimensionality reduction and plotting |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

Component-based models represent a significant advancement in single-cell computational biology, moving beyond discrete clustering to capture the continuous and multifaceted nature of cellular identity. The benchmarking data presented herein demonstrates that GEP-based approaches, particularly the TCAT/starCAT framework, offer substantial advantages for analyzing complex biological systems like T cell immunity.

The fixed coordinate system of GEPs enabled by TCAT/starCAT provides a reproducible foundation for comparing cellular states across experiments, donors, and disease conditions [3]. This addresses a critical challenge in single-cell biology, where batch effects and technical variability often obscure biological signals. The ability to project new datasets onto established GEP coordinates facilitates meta-analysis and integrative studies at unprecedented scale.

However, important challenges remain. The selection of appropriate factorization rank (number of components) continues to involve subjective elements, though methods like residual error analysis and consensus clustering provide guidance [32] [31]. Additionally, while nonnegativity enhances interpretability, it may limit the ability to model transcriptional repression, potentially necessitating complementary analyses for comprehensive regulatory inference.

Future methodological developments will likely focus on multimodal integration, simultaneously modeling gene expression, chromatin accessibility, and surface protein measurements within a unified factorization framework [3]. Temporal modeling approaches that capture dynamic program activation along developmental trajectories represent another promising direction. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, component-based models will play an increasingly essential role in translating high-dimensional molecular measurements into biological insight and clinical applications.

For researchers selecting among these methods, TCAT/starCAT provides superior performance for cross-dataset analysis and annotation tasks, particularly when studying T cell biology, while Spectra offers advantages when incorporating specific prior knowledge through gene-gene graphs [35]. Traditional NMF approaches remain valuable for exploratory analysis when established references are unavailable or when studying systems where comprehensive reference catalogs have not yet been developed.

The accurate annotation of cell types, particularly within the complex and plastic T cell compartment, is a critical step in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis. Reference-based annotation tools allow researchers to automatically classify cells from a new experiment (query dataset) by comparing them to expertly annotated reference atlases. This guide objectively compares three prominent tools—SingleR, Azimuth, and CellTypist—focusing on their performance, underlying methodologies, and application in benchmarking studies, with a specific emphasis on T cell subsets research.

Tool Comparison at a Glance

The following table summarizes the key characteristics and performance of SingleR, Azimuth, and CellTypist based on recent benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Reference-Based Annotation Tools

| Feature | SingleR | Azimuth | CellTypist |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Method | Correlation-based (Spearman) | Seurat integration & label transfer | Logistic regression models |

| Reference Handling | Pre-annotated reference dataset | Pre-processed and optimized reference map | Pre-trained or custom models |

| Benchmarked Performance (Xenium) | Best - Closest to manual annotation [38] [13] | Good | Not assessed in available studies |

| Benchmarked Performance (Lung Atlas) | Not assessed in top results | 85.8% overall accuracy [39] | 87.5% overall accuracy [39] |

| Strengths | Fast, accurate, easy to use [38] | Part of Seurat ecosystem; preserves reference structure [27] | Scalable to large references; supports online learning [39] |

| Considerations | Assigns a label to every cell (no "unknown" class by default) [12] | Requires reference building with Azimuth [38] | Performance can vary based on model and dataset [39] |

Performance and Experimental Data

Benchmarking on Spatial Transcriptomics Data

A 2025 study specifically benchmarked cell type annotation methods for 10x Xenium spatial transcriptomics data, which profiles only several hundred genes. Using a human HER2+ breast cancer dataset and a paired single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) reference, the study compared five reference-based methods against manual annotation based on marker genes.

In this challenging context with a limited gene panel, SingleR was the top-performing tool, with its predictions most closely matching the manual annotations. The study noted it was also fast and easy to use [38] [13]. Azimuth, scPred, and scmapCell also showed reasonable performance, while RCTD was found to be less suitable for this data type without significant parameter adjustment [13].

Benchmarking for Atlas Integration

Another benchmarking study focused on integrating cell types from two lung atlas datasets—the Human Lung Cell Atlas (HLCA) and the LungMAP single-cell reference (CellRef). The study evaluated tools based on their accuracy in matching query cells to expert-annotated reference labels [39].

Table 2: Lung Atlas Cross-Matching Performance

| Tool | Overall Accuracy | Macro F1 Score |

|---|---|---|

| CellTypist | 87.5% | 0.87 |

| Azimuth | 85.8% | 0.85 |

| scArches | 83.8% | 0.83 |

| FR-Match | 80.5% | 0.80 |

CellTypist achieved the highest overall accuracy and F1 score, a metric that balances precision and recall. The study highlighted that while both Azimuth and CellTypist performed well, they exhibited complementary strengths, with variations in accuracy when annotating specific and rare cell types [39].

Experimental Protocols in Benchmarking Studies

The robustness of the tool comparisons relies on standardized evaluation workflows. The following diagram illustrates the typical protocol used in the cited benchmarking studies.

Detailed Methodological Steps

- Data Collection and Reference Preparation: Benchmarking studies use publicly available or newly generated datasets. For example, a breast cancer Xenium dataset with a paired snRNA-seq reference was used to ensure minimal variability between reference and query [38] [13]. The reference data is meticulously annotated, often using marker gene expression and copy number variation (inferCNV) analysis to identify tumor cells [13].

- Query Data Preprocessing: The query data undergoes standard scRNA-seq preprocessing (quality control, normalization) using pipelines like Seurat. For spatial data like Xenium, which has a small gene panel, the feature selection step is sometimes skipped, and all genes are used for scaling [13].

- Tool Execution and Label Transfer: Each tool is run according to its specific requirements:

- SingleR: The

SingleR()function is applied directly to the normalized query data and the reference dataset [13]. - Azimuth: The reference is converted into an Azimuth-compatible object using

AzimuthReference(). The query is then annotated using theRunAzimuth()function, which projects it into the reference space [38] [13]. - CellTypist: A pre-trained model or a model built from the reference dataset is used to predict labels for the query cells [39].

- SingleR: The

- Performance Evaluation: Predictions from each tool are compared against the "ground truth" manual annotations. Metrics such as overall accuracy, F1 score, and the percentage of cells confidently annotated are calculated. The composition of predicted cell types is also compared to manual annotations to assess biological plausibility [38] [12] [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit

The table below lists key reagents and computational resources essential for performing reference-based cell type annotation as described in the experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Xenium Gene Panel | A pre-designed panel of several hundred genes for imaging-based spatial transcriptomics. | Generating query data for benchmarking on spatial platforms [38]. |

| Paired snRNA-seq Data | Single-nucleus RNA-seq data from the same sample as the spatial data. | Serves as an ideal, minimally variable reference dataset [13]. |

| Seurat R Toolkit | A comprehensive R package for single-cell genomics data analysis. | Used for data preprocessing, normalization, integration, and running Azimuth [38]. |

| Cell Type Marker Gene List | A curated list of genes known to be specifically expressed in particular cell types. | Used for manual annotation, which serves as the ground truth for benchmarking [12]. |

| inferCNV Software | A computational tool to infer copy number variations from scRNA-seq data. | Used to identify and annotate tumor cells in the reference atlas [13]. |

The choice of an optimal reference-based annotation tool depends on the specific biological context, data type, and research goals. For T cell research, where distinguishing between highly similar states (like exhausted and effector T cells) is crucial, the choice of a well-curated T-cell-specific reference is as important as the tool itself.

- SingleR excels in speed and accuracy, particularly on challenging data like imaging-based spatial transcriptomics, making it a robust and user-friendly choice [38] [13].

- Azimuth integrates seamlessly into the widely used Seurat workflow and is effective for projecting query data into a stable, curated reference atlas without altering its structure [27].

- CellTypist demonstrates high accuracy in large-scale atlas integration tasks and offers scalability for use with extensive reference collections [39].

Benchmarking studies consistently reveal that these tools have complementary strengths. Therefore, researchers working with T cell subsets may benefit from a consensus approach, using multiple tools to corroborate findings, especially when characterizing novel or rare cell states.