Beyond Animal Models: How New Approach Methods (NAMs) Are Revolutionizing Immunology Research and Drug Development

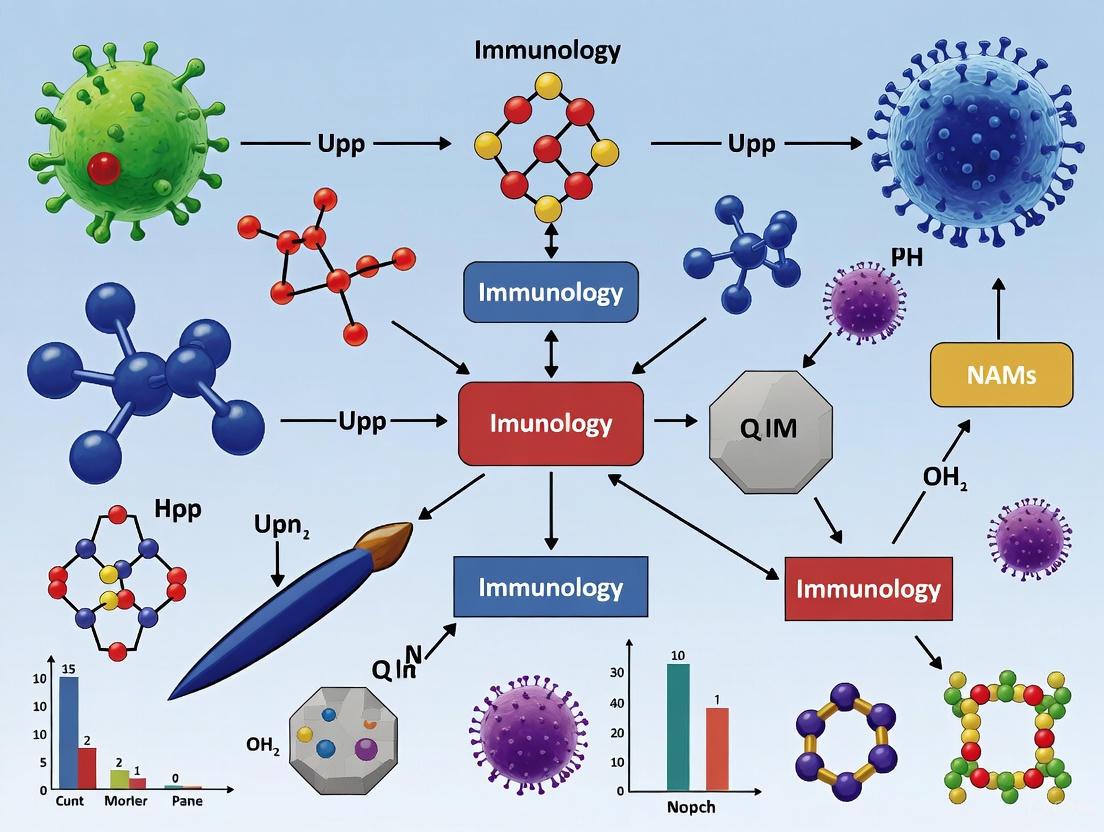

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the paradigm shift towards New Approach Methods (NAMs) in immunology.

Beyond Animal Models: How New Approach Methods (NAMs) Are Revolutionizing Immunology Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the paradigm shift towards New Approach Methods (NAMs) in immunology. Driven by ethical imperatives, economic pressures, and the significant translational gap between animal studies and human clinical outcomes—often called the 'valley of death'—NAMs offer human-relevant alternatives. We explore the scientific and regulatory foundations of this movement, detail cutting-edge methodological applications from organ-on-chip systems to in silico modeling, address key challenges in implementation and optimization, and analyze pathways for regulatory validation. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current initiatives from the FDA and NIH, showcases state-of-the-art technologies, and outlines a strategic framework for integrating NAMs into immunology research to enhance predictive accuracy and accelerate therapeutic discovery.

The Urgent Shift: Scientific and Regulatory Drivers for Adopting NAMs in Immunology

FAQs: Understanding the Translational Gap

What is the "Valley of Death" in translational immunology?

The "Valley of Death" refers to the critical gap where promising discoveries from laboratory research, often using animal models, fail to become effective human therapies [1]. In immunology, this is driven by the poor predictive value of traditional animal models for human immune responses, leading to a high failure rate of drugs in clinical trials [2] [3].

Why do animal models often fail to predict human immune responses?

Animal models, particularly rodents, have significant evolutionary divergences from human immunology. These include differences in immune cell subset heterogeneity, cytokine/chemokine biology, Toll-like receptor function, and vascular-immune cross-talk [3]. Approximately 1,600 immune-response genes in mice do not directly match their human equivalents, complicating the extrapolation of results [4].

What are New Approach Methods (NAMs) and how can they help?

New Approach Methods (NAMs) are non-animal, human-relevant research tools that include organ-on-chip systems, 3D organoids, advanced in silico modelling, and human-based immune cell cultures [2] [5]. These methods are driven by ethical, economic, and scientific motivations, and are designed to better mimic human physiology, thereby helping to bridge the translational gap [2].

Are there situations where animal models are still indispensable?

Yes, animal models remain valuable for studying complex, multi-organ immune processes that current NAMs cannot yet fully replicate. This includes investigating the dynamic cross-talk between a diseased tissue, peripheral blood, lymph nodes, and other organs, which is crucial for understanding overall immune response in areas like cancer immunotherapy [3].

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Poor Translational Outcomes in Preclinical Studies

Problem: Your therapeutic shows efficacy in animal models but fails in human trials.

| Recommended Action | Rationale | Specific Tools & Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Incorporate Humanized Models | Use THX mice or other advanced humanized mouse models that mount a more robust, human-like antibody response [4]. | THX mice: Created by injecting human stem cells; develop human lymph nodes, antibodies, and T/B cells [4]. |

| Adopt a Reverse Translation Approach | Start with human clinical data ("big data") to identify evolutionarily conserved immune phenotypes before testing in animals [3]. | Multi-omics profiling: Integrate transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data from human patients to guide animal model selection [6] [3]. |

| Integrate Organ-on-Chip Systems | Model human organ-level interactions and immune responses more accurately than in isolated animal tissues [4] [5]. | Multi-organ-on-chip (multi-OoC): Systems that replicate systemic immunological processes by integrating various human tissues and immune cells [2]. |

Challenge 2: Modeling the Complexity of Human Inflammatory Diseases

Problem: It is difficult to recapitulate the heterogeneity and progression of human inflammatory diseases (e.g., sepsis) in a controlled lab setting.

| Recommended Action | Rationale | Specific Tools & Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Refine Animal Models with Comorbidities | Standard, healthy animal models do not reflect the clinical reality of patients with underlying conditions [6]. | MQTiPSS Guidelines: Follow Minimum Quality Threshold in Pre-Clinical Sepsis Studies guidelines; incorporate chronic stress, diabetes, or other comorbidities into animal models [6]. |

| Use Human Ex Vivo Models | Leverage postmortem human tissues or advanced cell cultures that maintain native immune cell characteristics [2]. | Postmortem Tissue Studies: Viable human tissues can be used for immunological studies within 8-14 hours of death [2]. 3D Full-Thickness Skin Models: Immunocompetent models with integrated dendritic cells for studying inflammatory responses [2]. |

| Focus on Late-Acting Mediators | In diseases like sepsis, targeting early mediators like TNF has failed. Shift focus to later-acting mediators with wider therapeutic windows [6]. | Target HMGB1 & pCTS-L: These later-acting mediators offer a more promising therapeutic window than early cytokines like TNF [6]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and models essential for modern, human-relevant immunology research.

| Reagent / Model | Function & Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| THX Mouse Model [4] | A humanized mouse model for vaccine research and studying human immune responses to pathogens like HIV and COVID-19. | Mounts a strong antibody response to mRNA vaccines; does not require complicated tissue engraftments. |

| Organ-on-Chip / Organoid Systems [4] | Miniature models of human organs (gut, liver, lung) for studying disease mechanisms and drug responses without animals. | Provides a more accurate model of human biology than animal models; endorsed by FDA and NIH for drug safety trials. |

| scRNA-seq with CITE-seq [4] | Single-cell RNA sequencing combined with protein surface marker detection to map immune cell types and functions in high resolution. | Uncover specific immune cell types (e.g., three main types of NK cells) and their roles in cancer and other diseases. |

| 3D Full-Thickness Skin Model [2] | An in vitro model with integrated dendritic cells for testing skin sensitization and inflammatory responses to compounds. | Effectively mimics immune responses to sensitizers and can be used to test anti-inflammatory compounds. |

| 24-Color Flow Cytometry Panel [2] | A high-throughput panel for comprehensive immunophenotyping of human peripheral blood cells to screen chemical effects. | Facilitates the identification of affected immune cell types and signaling pathways in response to stimuli. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Implementing a Reverse Translation Workflow

This protocol outlines a strategy to bridge the evolutionary gap between animal models and human immunology by starting with human data.

1. Generate Human Patient 'Big Data': Collect and integrate multi-omics data (transcriptomic, proteomic) from human patients with their clinical response variables [3]. 2. Computational Bridging: Use multi-dimensional computational approaches to identify evolutionarily conserved immune pathways and targets between humans and animal models [3]. 3. Tailored Animal Modeling: Select or create animal models (e.g., humanized mice, models with comorbidities) that most closely mirror the context of the human disease-immune cross-talk identified in Step 2 [6] [3]. 4. Forward Translation: Test novel immunotherapies or biomarkers in the tailored models before proceeding to human clinical trials [3].

Reverse Translation Workflow

Protocol 2: Developing an Immunocompetent Organ-on-Chip Model

This methodology details the creation of a microfluidic platform to model human vascular inflammation, a key process in many immune diseases [2].

1. Platform Setup: Use a scalable microfluidic platform with 64 parallel channels, each lined with human endothelial cells [2]. 2. Real-Time Measurement: Integrate a system for real-time measurement of endothelial barrier function via transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) [2]. 3. Introduce Immune Stimuli: Apply cytokines or immune cells to the system to induce an inflammatory response [2]. 4. Monitor Key Parameters: Measure changes in barrier function, adhesion molecule expression (e.g., ICAM-1, VCAM-1), and immune cell migration in real-time [2]. 5. Drug Screening Application: Use the calibrated platform to screen potential anti-inflammatory drugs by assessing their ability to normalize the measured parameters [2].

Quantitative Limitations of Traditional Animal Models

| Limitation | Data / Evidence | Impact on Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Divergence | Over 1,600 immune-response genes in mice lack direct human equivalents [4]. | Poor prediction of drug efficacy and toxicity in humans. |

| Antibody Response | Most humanized mice fail to mount a strong antibody response to vaccines [4]. | Hampers vaccine and infectious disease research. |

| Species-Specific Biology | Fundamental differences in NK cell biology, T-cell repertoire, and cytokine networks exist [3]. | Mechanisms of action discovered in animals may not hold in humans. |

| Model Homogeneity | Animal models use genetically identical subjects with standardized insults, unlike heterogeneous human populations [6]. | Fails to predict treatment outcomes across diverse human patients. |

Comparison of Advanced Research Models

| Model | Key Advantage | Primary Application | Key Quantitative Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| THX Mice [4] | Strong human-like antibody response. | Vaccine research, B-cell biology. | Mounted a strong immune response to an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. |

| Organ-on-Chip (Vascular) [2] | Real-time monitoring of barrier function. | Vascular inflammation, drug screening. | Enabled real-time TEER measurement in 64 parallel microfluidic channels. |

| 3D Skin Model with DCs [2] | Mimics native tissue immune response. | Skin sensitization, toxicity testing. | Integrated dendritic cells responded to sensitizers by upregulating maturation markers. |

| Postmortem Tissue Studies [2] | Direct access to human tissue immune responses. | Tuberculosis, tissue-specific immunology. | Maintained cell viability for immunological studies up to 14 hours postmortem. |

Foundational Concepts: The 3Rs and New Approach Methodologies (NAMs)

What are the 3Rs? The 3Rs are a guiding principle for the ethical use of animals in science. Established over 65 years ago, they provide a framework for humane animal research [7]:

- Replace: Substituting animal use with non-animal systems like computer models, biochemical assays, or less-developed animal species.

- Reduce: Using the minimum number of animals necessary to achieve research objectives.

- Refine: Modifying procedures to eliminate or minimize pain and distress and to enhance animal well-being.

What are New Approach Methodologies (NAMs)? NAMs are innovative, human-relevant tools that do not rely solely on traditional animal testing [7] [8]. They are designed to provide more predictive data for human safety and efficacy. Key categories include:

- In chemico: Experiments on biological molecules (e.g., proteins, DNA) outside of cells.

- In silico: Experiments using computational platforms, including mathematical modeling, simulation, and artificial intelligence (AI).

- In vitro: Experiments on cells outside the body, including advanced models like organoids and organs-on-chips.

Frequently Asked Questions for the Practicing Scientist

Q1: We must provide animal data for regulatory submissions. Can we still use NAMs? Yes. Recent U.S. legislation and regulatory guidance actively encourage the use of NAMs. The FDA Modernization Act 2.0 (Dec 2022) removed the mandatory requirement for animal testing for drugs and explicitly defined "nonclinical tests" to include human biology-based methods like cell-based assays, microphysiological systems (MPS), and computer models [9] [10]. You are now authorized to submit data from these methods. Furthermore, the FDA's 2025 roadmap outlines a plan to phase out routine animal testing, making animal studies "the exception rather than the rule" [9] [10]. For specific contexts of use, engage with agency pilot programs like the FDA's ISTAND to qualify your novel drug development tool [9] [10].

Q2: Our complex immunology research involves systemic responses. Can NAMs truly replace animal models for this? For complex, multi-organ processes, a complete replacement is currently challenging. However, NAMs serve as powerful complementary tools. While some argue that whole living systems are still necessary to capture the complexity of interconnected organs [11], advanced Microphysiological Systems (MPS), such as multi-organ chips, are being developed to model interconnected human systems. A pragmatic approach is to use NAMs to reduce and refine animal use. For instance, use human-based in vitro models to prioritize the most promising drug candidates or to elucidate mechanistic pathways, thereby reducing the number of animals needed and refining the experiments that are ultimately conducted [8].

Q3: How do we validate a new NAM in our lab to ensure regulatory and scientific acceptance? Validation is a critical, multi-step process:

- Define a Clear Context of Use: Specify the exact purpose and application of your NAM.

- Generate Robust, Reproducible Data: Assess the method's reliability within your lab.

- Establish Human Relevance: Demonstrate that the NAM accurately predicts human biology or toxicology, for example, by using human primary cells or stem cell-derived tissues.

- Utilize Public Data Resources: Leverage tools like the Integrated Chemical Environment (ICE) to compare your results with existing reference data [7].

- Engage Early with Regulators: For drug development, consult with the FDA about the appropriateness of your NAM data for a specific application [8] [10].

- Seek Qualification Programs: Pursue formal qualification through pathways like the FDA's ISTAND pilot program, which accepted the first organ-on-a-chip (a Liver-Chip for DILI prediction) in 2024 [9].

Q4: What are the most immediate "low-hanging fruit" applications for NAMs in immunology? You can start integrating NAMs today in several areas:

- Early Safety Screening: Use high-throughput in vitro assays (e.g., from the Tox21 program) to screen for immunotoxicity or cytokine release syndrome risk, eliminating unsafe compounds before they ever reach an animal [7].

- Mechanistic Studies: Employ patient-derived organoids or immune cell-coated chips to study specific human immune pathways in a controlled environment.

- Disease Modeling: Utilize human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or macrophages in 3D culture systems to model human-specific inflammatory diseases.

Q5: Our grant funding requires animal use. Are there funding opportunities for NAMs development? Yes, funding priorities are shifting significantly. The NIH Complement-ARIE program is a major initiative to speed the development and use of human-based NAMs [7]. Critically, as of July 2025, the NIH announced that proposals relying exclusively on animal data will no longer be eligible for agency support. Your grant applications must now integrate at least one validated human-relevant method [9].

Experimental Protocols: Integrating NAMs into Your Workflow

Protocol 1: Implementing a Human Liver-Chip for Preclinical Hepatotoxicity Screening

This protocol outlines how to integrate a microphysiological system to reduce animal use in drug safety testing.

- Objective: To predict drug-induced liver injury (DILI) using a human-relevant in vitro model prior to rodent or non-rodent studies.

- Background: A landmark study demonstrated that a human Liver-Chip showed 87% sensitivity and 100% specificity in predicting DILI for a set of drugs, outperforming animal models [9].

- Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Seed a microfluidic chip with primary human hepatocytes, hepatic stellate cells, and Kupffer cells to recreate the liver sinusoid.

- Perfusion Culture: Maintain the chip under physiological fluid flow to provide shear stress and nutrient exchange.

- Dosing: Introduce the drug candidate into the perfusion medium at a range of clinically relevant concentrations.

- Endpoint Analysis:

- Biomarker Assays: Measure albumin, urea, and ALT/AST levels in the effluent daily.

- Immunofluorescence: Stain for tight junction proteins (ZO-1) and bile canaliculi to assess structural integrity.

- RNA Sequencing: Analyze transcriptomic changes to uncover mechanisms of toxicity.

- Integration with Animal Studies: Data from the Liver-Chip can be used to prioritize which drug candidates advance to in vivo studies and to inform dosing levels, reducing the number of animals required and refining the study design [9].

Protocol 2: An In Silico Workflow for Reducing Animal Use in Immunogenicity Risk Assessment

This protocol uses computational tools to reduce the need for animal immunogenicity studies.

- Objective: To predict the potential immunogenicity of a biologic drug candidate (e.g., a monoclonal antibody) using in silico tools.

- Background: AI/ML approaches can analyze complex datasets to identify sequences with a high risk of eliciting an anti-drug antibody (ADA) response.

- Methodology:

- Sequence Analysis: Input the protein sequence of the biologic into an in silico tool (e.g., from the CATMoS framework or similar platforms) to identify T-cell and B-cell epitopes that match common human HLA alleles [10].

- Aggregation Propensity Prediction: Use tools like TANGO or PASTA to predict regions prone to aggregation, as aggregates can increase immunogenicity.

- Glycosylation Pattern Analysis: Predict glycosylation sites and potential non-human glycan structures.

- Data Integration and Risk Scoring: Combine the outputs from the various in silico analyses to generate a composite immunogenicity risk score for the candidate molecule.

- Outcome: Candidates with a high predicted immunogenicity risk can be re-engineered or deprioritized before any in vivo immunogenicity studies are initiated in transgenic mice or other animal models, leading to a significant reduction in animal use.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials for Advanced In Vitro and In Silico Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Human Cells | Provides human-relevant biological data; sourced from donors or stem cells. | Creating patient-specific disease models in organoids or chips [8]. |

| Organ-on-a-Chip (MPS) | Microfluidic devices that emulate human organ physiology and function. | Predicting drug-induced liver injury (DILI) with high accuracy [9]. |

| 3D Organoids | Miniature, simplified 3D tissue structures grown from stem cells. | Modeling human intestinal or lung tissue for infection or toxicity studies [7]. |

| AI/ML Analytics Software | Analyzes complex 'omics datasets and generates predictive models of toxicity or efficacy. | Building a model to prioritize chemicals for testing based on structural similarity [7] [8]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Assays | Allows for rapid testing of thousands of compounds using automated, cell-based systems. | Tox21 program screening of ~10,000 chemicals for biological activity [7]. |

Regulatory and Workflow Diagrams

Regulatory Paths: Traditional vs. NAMs-Integrated

NAM Development and Regulatory Ecosystem

The landscape of biomedical research is undergoing a fundamental transformation. Driven by the recognition that animal models often fail to predict human outcomes, major U.S. regulatory and research agencies are actively shifting the field toward human-relevant, non-animal methods [12] [13] [14]. This change is embodied in two pivotal initiatives: the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) 2025 "Roadmap to Reducing Animal Testing" and the National Institutes of Health's (NIH) plan to establish the Office of Research Innovation, Validation, and Application (ORIVA) [12] [15] [14]. This technical support center is designed to help you, the researcher, navigate this transition by providing practical guidance on implementing New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) in your work, with a focus on immunology and drug development.

The Regulatory Framework

What are the key objectives of the FDA's 2025 Roadmap and NIH's ORIVA initiative?

The FDA's Roadmap and the NIH's ORIVA initiative represent a coordinated effort within the Department of Health and Human Services to reduce and eventually eliminate the reliance on animal testing in biomedical research and drug development [14].

FDA's 2025 Roadmap: This strategic document outlines a plan to phase out animal testing requirements, starting with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and eventually expanding to other biological molecules and new chemical entities [15] [14]. Its key objectives include:

- Promoting NAMs: Encouraging the use of advanced tools like organ-on-a-chip systems, computational modeling, and advanced in vitro assays for safety and efficacy evaluations [15] [14].

- Regulatory Incentives: Offering streamlined reviews and regulatory relief to sponsors who submit strong NAMs data [15] [16].

- Pilot Programs: Launching pilot programs allowing selected developers to use primarily non-animal-based testing strategies [15].

- Long-Term Vision: The FDA's stated goal is to make animal studies the exception, not the norm, within 3-5 years [17].

NIH's ORIVA Initiative: The new Office of Research Innovation, Validation, and Application (ORIVA) will coordinate NIH-wide efforts to integrate human-based science [12]. Its core functions are:

- Coordination: Serving as a hub for developing, validating, and scaling non-animal approaches across the NIH's research portfolio [12].

- Funding and Training: Expanding funding opportunities and training programs focused on NAMs [12].

- Bias Mitigation: Providing training for grant review staff to address potential bias towards animal studies and integrating experts on alternative methods into study sections [12].

What is the evidence supporting this shift away from animal models?

The regulatory shift is driven by significant scientific and economic evidence highlighting the limitations of animal models and the promise of human-based methods.

Table 1: Documented Limitations of Animal Models

| Category | Specific Example | Impact/Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Safety Failures | Fialuridine: No significant toxicity in mice, rats, or dogs; caused fatal hepatic failure in humans [13]. | Late-stage clinical failure, patient harm. |

| Safety Failures | Troglitazone: Safe in animals; withdrawn from market due to human liver failure [13]. | Drug withdrawal, public health risk. |

| Safety Failures | Rofecoxib: No safety signals in animals; increased risk of heart attack and stroke in humans [13]. | Post-market safety issues. |

| Immunology Disconnect | TGN1412 mAb: Appeared safe in monkey studies; caused life-threatening cytokine release syndrome in humans [18] [17] [16]. | Clinical trial crisis, near-fatalities. |

| Immunology Disconnect | Ipilimumab: Minimal safety concerns in NHPs; highest incidence of immune-related adverse events among early immunotherapies in clinic [18]. | Poor prediction of human immune toxicity. |

| Efficacy Failures | Over 90% of drugs that appear safe/effective in animals fail in human trials due to lack of efficacy or unexpected safety issues [13] [14] [17]. | High R&D attrition, costing billions of dollars. |

Table 2: Quantitative Economic Impact of Traditional mAb Testing

| Metric | Traditional Animal-Centric Approach | Potential NAM Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Use | ~144 non-human primates (NHPs) per program [17] [16]. | Significant reduction; goal to waive studies [17]. |

| Cost per Animal | Up to $50,000 per NHP [16]. | Reduced animal costs. |

| Timeline | Up to 9 years per therapeutic [17]. | Accelerated development. |

| Total Program Cost | \$650-\$750 million [17]. | Potential for significant reduction. |

Implementing NAMs: Core Technologies & Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key NAMs relevant to immunology research.

FAQ: What are the core NAM technologies, and how do I choose?

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) encompass a suite of human-based tools. Selecting the right one depends on your research question and the required context of use (COU) [18] [19].

Table 3: Core NAM Technologies and Their Applications

| Technology Category | Key Examples | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Models | Organoids, Spheroids, Organ-on-a-Chip [12] [19] | Disease modeling (e.g., cancer, inflammatory conditions), capture patient-specific characteristics, toxicity screening [12] [17]. |

| In Silico Models | AI/ML predictive models, PBPK models, QSP models [12] [18] [19] | Predicting drug toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and human immunogenicity; simulating complex biological systems [15] [13]. |

| Omics Technologies | Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics [19] | Mechanistic insights, biomarker discovery, pathway analysis aligned with Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs) [19]. |

| Integrated Strategies | IATA (Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment), ITS (Integrated Testing Strategies) [19] | Combining data from multiple NAMs (e.g., in vitro + in silico) for a weight-of-evidence safety assessment [19]. |

Experimental Protocol 1: Establishing a 3D Immune-Competent Organoid Co-culture for Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) Assessment

Background: This protocol is designed to model TGN1412-like cytokine release syndrome using a human-based system, providing a more predictive safety assessment than non-human primates [18] [17] [16].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Cell Sourcing and Preparation:

- Primary Human Immune Cells: Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donor blood using density gradient centrifugation (e.g., Ficoll-Paque). Alternatively, use cryopreserved PBMCs.

- Target Tissue Cells: Source human primary endothelial cells (e.g., HUVECs) or hepatocytes (for liver-chip models). Alternatively, use relevant human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived cell types [17] [16].

- Culture Media: Maintain cells in their respective optimized media prior to co-culture.

3D Matrix Embedding:

- Prepare a basement membrane matrix (e.g., Matrigel or a synthetic hydrogel) on ice.

- Mix the target tissue cells (endothelial/hepatocytes) with the matrix at a predetermined density.

- Plate the cell-matrix mixture in a 96-well plate or on the chip channel of an organ-on-a-chip device. Allow polymerization at 37°C for 30-60 minutes [17].

Co-culture Establishment:

- Gently add immune cells (PBMCs) in suspension to the top of the polymerized 3D structure or introduce them into the adjacent channel in a microfluidic device.

- Use a co-culture medium that supports both cell types. For microfluidic systems, initiate perfusion to mimic blood flow and enable immune cell recruitment [17] [19].

Compound Dosing:

- After a stabilization period (e.g., 24-48 hours), expose the co-culture to the therapeutic mAb or biologic.

- Include controls: a negative isotype control antibody and a positive control known to cause CRS (e.g., anti-CD28 superagonist).

- Test a range of concentrations relevant to predicted clinical exposure.

Assay and Analysis:

- Time Course Sampling: Collect supernatant from the culture at 0, 6, 24, and 48 hours post-dosing.

- Cytokine Profiling: Use a multiplex immunoassay (e.g., Luminex) to quantify a panel of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α).

- Viability Assessment: At endpoint, perform a cell viability assay (e.g., Calcein-AM/EthD-1 live/dead staining) on the tissue cells.

- Imaging: Use confocal microscopy to visualize immune cell adhesion and infiltration into the tissue layer (using fluorescently labeled immune cells).

Experimental Protocol 2: Leveraging AI/ML and QSP Modeling for First-in-Human (FIH) Dose Prediction

Background: This in silico protocol integrates NAM-derived data with mechanistic modeling to inform FIH dose selection, reducing reliance on animal pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies [18].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Input and Curation:

- Internal NAM Data: Input data from in vitro assays, such as:

- Target affinity (e.g., KD from surface plasmon resonance).

- Cellular potency (e.g., EC50 from a cell-based reporter assay).

- Human hepatocyte data for clearance prediction.

- External/Public Data: Curate large-scale datasets for model training. This includes:

- Internal NAM Data: Input data from in vitro assays, such as:

AI/ML Model Training:

- Feature Engineering: Identify critical parameters influencing human PK/PD (e.g., molecular weight, charge, in vitro clearance, target expression).

- Model Selection: Train a machine learning model (e.g., gradient boosting or random forest) using data from approved therapeutics to predict human clearance, volume of distribution, and ultimately, clinical exposure profiles [18].

QSP Model Development:

- Build or adapt a existing QSP platform that mathematically represents the biological system relevant to your drug's mechanism (e.g., a T cell engager QSP model for a bispecific antibody).

- Calibrate the model using the in vitro NAM data (e.g., incorporating on-target effect and cytokine release data from Protocol 1) [18].

Model Integration and Simulation:

- Integrate the outputs of the AI/ML-predicted PK with the QSP model's PD components.

- Run thousands of virtual trials using the integrated model to simulate a range of dosing scenarios and predict efficacy and toxicity margins in a diverse virtual human population [18].

FIH Dose Recommendation:

- Based on the simulations, identify a safe starting dose (e.g., a dose expected to achieve 10% of the maximum effect with a high safety probability) and a dose-escalation scheme for the clinical trial [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for Human-Based Immunology NAMs

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Human Cells | Provide species-relevant biology; source for organoids and co-cultures. | PBMCs, primary hepatocytes, HUVECs. Use donor-matched sets for consistent results. iPSCs offer a scalable alternative [17]. |

| 3D Culture Matrices | Provide a physiologically relevant scaffold for 3D cell growth and signaling. | Basement membrane extracts (e.g., Matrigel), synthetic hydrogels (e.g., PEG-based). Select based on stiffness and composition for your tissue type [17]. |

| Specialized Culture Media | Support the complex metabolic needs of multi-cell type co-cultures. | Commercially available organoid media or custom formulations. Avoid serum to reduce variability. Include key cytokines for immune cell survival [17]. |

| Cytokine Detection Kits | Quantify immune activation and cytokine release syndrome (CRS) in response to therapeutics. | Multiplex bead-based immunoassays (e.g., Luminex). Essential for safety assessment of immunotherapies [16]. |

| Microfluidic Devices | Enable organ-on-a-chip cultures with perfusion, mechanical stress, and tissue-tissue interfaces. | Commercially available liver-chips, immune-chips. Recreate key aspects of human physiology not possible in static wells [17] [19] [16]. |

| AI/ML & Modeling Software | Analyze high-dimensional NAM data, build predictive models, and simulate human physiology. | PBPK platforms (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp), QSP software, and general data science tools (e.g., Python/R with ML libraries) [18] [19]. |

Troubleshooting Common NAMs Challenges

FAQ: My NAMs data is highly variable. How can I improve reproducibility?

Variability is a major challenge in early NAMs adoption. Standardization is key to regulatory acceptance [18] [13].

- Define a Clear Context of Use (COU): Early in development, precisely define what question the NAM is intended to answer. This focuses the model's complexity on clinically relevant outcomes and guides standardization efforts [18].

- Standardize Protocols: Use standardized, commercially available platforms where possible. For in-house protocols, document and rigorously adhere to detailed SOPs for cell sourcing, passage number, matrix lot, and media formulation [13] [17].

- Incorporate Robust Controls: Always include benchmark compounds (both positive and negative controls) in every experiment. This allows for cross-experiment and cross-laboratory data normalization and validation [18].

- Utilize Centralized Resources: Leverage new infrastructure like the NIH's $87 million Standardized Organoid Modeling (SOM) Center, which is specifically designed to address reproducibility by creating standardized protocols and models [17].

FAQ: How can I gain regulatory acceptance for NAMs data in my IND submission?

Engaging with regulators early and building a robust scientific rationale is critical.

- Engage Early via FDA INTERACT Meetings: For innovative programs, the FDA's INTERACT meeting provides informal, early feedback on your proposed use of NAMs, helping to align your strategy with regulatory expectations [20].

- Adopt a "Weight-of-Evidence" Approach: Regulators are more likely to accept NAMs data when it is part of an Integrated Testing Strategy (IATA). Combine data from multiple complementary NAMs (e.g., in vitro cytokine release + in silico PBPK/QSP modeling) to build a compelling case [18] [19].

- Generate Retrospective Validation Data: If possible, demonstrate that your NAM can correctly predict the clinical outcomes of known drugs (both safe and toxic). The Emulate Liver-Chip, for example, was validated by correctly identifying 87% of known hepatotoxic drugs [16].

- Participate in Pilot Programs: The FDA is actively seeking "pilot cases" where sponsors propose to waive animal studies based on strong NAM data. Volunteering for these programs provides a pathway for acceptance and helps shape future policy [15] [17].

FAQ: My NAM is complex but doesn't directly predict clinical doses. What should I do?

Rich mechanistic data from complex NAMs often needs translation to be clinically useful.

- Integrate with Mechanistic Models: Bridge the gap by feeding NAM outputs into Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) or Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models. For instance, in vitro efficacy data from an organoid can be used to parameterize a QSP model, which then simulates human dose-response relationships [18].

- Focus on Comparative Assessment: For next-in-class drugs, use your NAM to compare your candidate to a clinically approved benchmark. Demonstrating a comparable or improved safety/efficacy profile in the human-based system provides strong supportive evidence for your FIH dose strategy [18].

- Use for De-risking, Not Just Approval: Even if not used as a primary justification for a clinical dose, NAMs are powerful for internal decision-making. They can help prioritize the best candidate molecule, identify potential safety liabilities early, and guide clinical monitoring strategies [16].

FAQ: Troubleshooting Guide for Immunotoxicity Risk Assessment

Q1: Our therapeutic monoclonal antibody passed all standard in vitro and animal model safety tests. How can we better assess the risk of a "cytokine storm" in humans before first-in-human trials?

A: The TGN1412 tragedy demonstrated critical gaps in traditional testing. A modern, robust risk assessment should include the following troubleshooting steps and advanced protocols:

Problem: Standard cell suspension assays fail to detect superagonist activity.

- Solution: Implement a solid-phase assay where the therapeutic antibody is immobilized on a surface. Serendipitous research following the TGN1412 incident found that while the antibody caused no activation in liquid suspension, it provoked a massive cytokine release when coated onto plastic plates [21]. This mimics the cell-surface binding conditions more accurately.

Problem: Animal models do not predict human-specific immune responses.

- Solution: Utilize humanized in vitro systems. For TGN1412, a key difference was found in the expression of CD28 on CD4+ effector memory T-cells between humans and non-human primates, despite high sequence homology [22]. Prioritize tests on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or other human-derived immune cell cultures.

Problem: Inadequate characterization of cytokine release profile.

- Solution: Employ multiplex cytokine arrays to quantify a broad panel of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Research correlating with the TGN1412 disaster severity specifically identified the level of IL-2 release as a key differentiator from other mAbs [22]. Flow cytometry can further identify the specific immune cell subsets (e.g., Th1, Th2, Th17) responsible for cytokine production [22].

Q2: What are the critical New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) for de-risking immunomodulatory biologics?

A: The field of immunology is increasingly adopting human-relevant NAMs to bridge the translational gap. Key methodologies include [2]:

- Advanced In Vitro Models: 3D tissue models (e.g., full-thickness skin models with integrated immune cells), human organ-on-chip systems (e.g., microfluidic platforms for modeling vascular inflammation), and the use of primary human immune cells in defined co-cultures.

- In Silico Modeling: Mechanistic computational models, including agent-based models, to simulate complex immune responses and predict inflammatory cascades without using animals.

- High-Throughput Immunophenotyping: Comprehensive, multi-color flow cytometry panels (e.g., 24-color) for high-throughput screening of chemicals and biologics on human PBMCs to identify affected cell types and signaling pathways.

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Preclinical Safety

Protocol: Solid-Phase T-Cell Activation Assay

This protocol is designed to detect the superagonistic activity of immunomodulatory antibodies, which may be missed in conventional assays [21] [22].

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Human PBMCs | Source of primary human T-cells for a physiologically relevant response. Isolate from healthy donors. |

| Anti-CD28 mAb (Test Article) | The immunomodulatory agent being investigated (e.g., TGN1412). |

| Control mAbs | Include an isotype control (negative) and a known T-cell mitogen like anti-CD3 (positive). |

| 96-Well Plate | Solid surface for immobilizing the antibody. |

| Cytokine Multiplex Array | For quantifying a broad panel of cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17). |

| Flow Cytometer | For immunophenotyping activated T-cell subsets and intracellular cytokine staining. |

2. Methodology

- Step 1: Antibody Immobilization. Prepare the test and control antibodies in a suitable coating buffer. Add the solutions to the wells of a 96-well plate and incubate overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, block the plates with a protein-based buffer to prevent non-specific binding [21].

- Step 2: Cell Seeding and Stimulation. Isolate PBMCs from human donors. Seed the cells into the antibody-coated wells. Include control wells with cells only and mitogen-stimulated cells. Incubate for 24-48 hours at 37°C and 5% CO₂ [22].

- Step 3: Supernatant and Cell Harvesting. Carefully collect the supernatant from each well and store at -80°C for cytokine analysis. Harvest the cells for flow cytometric analysis.

- Step 4: Analysis.

- Cytokine Release: Use the multiplex array to measure cytokine concentrations in the supernatant. A significant release of IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α is a major red flag for a potential "cytokine storm" [22].

- Immunophenotyping: Stain the cells for surface markers (e.g., CD4, CD8, CD25) and intracellular cytokines (e.g., IL-2) to identify the specific T-cell populations being activated.

Protocol: Cross-Species CD28 Expression and Function Analysis

This protocol assesses critical species-specific differences that may invalidate animal models for a particular drug candidate [23] [22].

1. Methodology

- Step 1: Cell Sourcing. Obtain PBMCs or purified T-cells from humans and relevant preclinical species (e.g., cynomolgus monkey, rhesus monkey).

- Step 2: Flow Cytometric Analysis. Stain cells with fluorescently labeled anti-CD28 antibodies and antibodies against T-cell subsets (e.g., CD4, CD8, CD45RO for memory T-cells). Analyze the percentage of CD28-positive cells and the receptor density (Mean Fluorescence Intensity) on different T-cell subsets, particularly CD4+ effector memory T-cells [22].

- Step 3: Functional Assay. Perform the solid-phase T-cell activation assay (as described in Protocol 2.1) in parallel using cells from each species. Compare the magnitude and profile of cytokine release.

2. Data Interpretation

- A negative or weak response in animal cells alongside a strong response in human cells indicates a critical species difference, as was the case with TGN1412. This finding should trigger extreme caution in extrapolating animal safety data to humans.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from the TGN1412 case and related research.

Table 1: Comparison of TGN1412 Effects in Preclinical vs. Clinical Studies

| Parameter | Preclinical (Non-Human Primates) | Clinical (Human Volunteers) |

|---|---|---|

| Max Tolerated Dose | 50 mg/kg (NOAEL) [23] | Life-threatening at 0.1 mg/kg (500x lower) [23] |

| Primary Symptom | Well-tolerated, moderate cytokine increase [23] | Cytokine storm, multi-organ failure [24] |

| T-cell Response | Proliferation and expansion [23] | Severe and rapid depletion (lymphopenia) [24] |

| Key Cytokines | Moderate, transient increase in IL-2, IL-5, IL-6 [23] | Massive, rapid release of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-6 [24] [22] |

| CD28+ Expression on CD4+ Effector Memory T-cells | Low or absent [22] | High [22] |

Table 2: Cytokine Release Profile of TGN1412 vs. Other mAbs in Solid-Phase Assay [22]

| Therapeutic mAb | IL-2 Release (pg/ml) | IFN-γ Release | Key T-cell Subsets Activated |

|---|---|---|---|

| TGN1412 | 2894 - 6051 | Significant | Th1, Th2, Th17, Th22 |

| Muromonab (OKT3) | 62 - 262 | Significant | Polyclonal T-cells |

| Alemtuzumab | Not Significant | Not Significant | - |

| Bevacizumab | Not Significant | Not Significant | - |

Visualizing the Mechanistic Failure and New Testing Paradigm

The diagram below illustrates the immunological mechanism behind the TGN1412 tragedy and how modern assays detect this risk.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Immunotoxicity Testing

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Immunotoxicity Assessment

| Reagent / Material | Function in Assay |

|---|---|

| Human PBMCs from Multiple Donors | Provides a genetically diverse source of primary human immune cells for assessing inter-individual variability. |

| Cryopreserved Human Immune Cell Subsets | Enables specific study of isolated cell types (e.g., CD4+ T-cells, regulatory T-cells). |

| Recombinant Human Proteins & Antibodies | Positive and negative controls for assay validation (e.g., anti-CD3 for T-cell activation). |

| Multiplex Cytokine Detection Kits | Allows simultaneous, quantitative measurement of a wide array of cytokines from a small sample volume. |

| Flow Cytometry Panels (12+ colors) | Enables deep immunophenotyping of cell surface and intracellular markers to identify responding cell populations. |

| 3D Human Tissue Constructs | Provides a more physiologically relevant microenvironment for studying immune cell migration and function. |

| Microfluidic Organ-on-Chip Platforms | Models systemic immune responses and inter-organ communication in a human-relevant context [2]. |

The Unique Challenges of Modeling the Human Immune System for NAM Development

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Lack of Standardization in Human Immune NAMs

A primary hurdle in adopting New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) for immunology is the lack of standardized, reproducible protocols across different laboratories. The recent launch of the NIH's $87 million Standardized Organoid Modeling (SOM) Center directly addresses this by funding efforts to create robust, high-throughput platforms capable of delivering regulatory-ready data [17].

- Problem: High inter-laboratory variability in immune NAMs (e.g., organoids, organ-on-chip) due to non-standardized protocols.

- Symptoms: Inconsistent results between batches or labs; regulatory reluctance to accept data; difficulty comparing studies.

- Solution: Develop a clearly defined Context of Use (COU) for your NAM. The FDA encourages sponsors to propose specific cases, such as for monoclonal antibodies targeting human-specific receptors, where animal studies can be waived based on a strong scientific rationale and robust NAM data [17] [18].

- Preventative Steps:

- Utilize foundational models and shared decoders to align data types, as demonstrated in top-performing machine learning challenges for immunology [25].

- Implement a fit-for-purpose approach. Start with simpler, well-defined assays (e.g., 2D T-cell cytotoxicity assays) that have a clear path to regulatory acceptance for specific endpoints, before moving to more complex systems [18].

Guide 2: Incorporating Critical Immune Components

The 2025 Nobel Prize highlighted that immune tolerance is actively maintained by regulatory T cells (Tregs), not merely the absence of activation. This underscores the need for immune-competent models that capture such dynamic balances [26].

- Problem: Models lack key immune populations or interactions, failing to recapitulate essential processes like active tolerance or cytokine storms.

- Symptoms: Inability to predict immunotoxicity (e.g., drug-induced liver injury); poor translation of efficacy from model to human; missing key adverse events like cytokine release syndrome.

- Solution: Integrate immune components to model the full immune cycle. This can be achieved by:

- Example Protocol: Generating a 3D full-thickness skin model with integrated dendritic cells [2].

- Culture a full-thickness human skin equivalent.

- Incorporate dermal dendritic cell surrogates (e.g., derived from THP-1 cells) into the model.

- Apply the test compound (e.g., sensitizer) topically.

- Assay by measuring dendritic cell activation markers (e.g., CD86, CD54) via flow cytometry and cytokine secretion via ELISA.

Guide 3: Translating Complex NAM Data to Clinical Outcomes

A key strength of in vitro NAMs is generating human-relevant mechanistic data, but these rich datasets (e.g., transcriptomics, spatial imaging) are often difficult to correlate directly with clinical outcomes [18].

- Problem: Inability to translate high-dimensional NAM data (e.g., transcriptomic changes) into predictions for first-in-human (FIH) dose or safety margins.

- Symptoms: "Data-rich, but information-poor" outcomes; uncertainty in how NAM results inform clinical trial design.

- Solution: Integrate NAMs with computational modeling and AI.

- Leverage AI/ML: Use artificial intelligence to analyze deep phenotypic readouts from NAMs and anchor them to known clinical outcomes of benchmark drugs [18].

- Employ Mechanistic Models: Use Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models to extrapolate drug disposition from multi-organ-chip systems, or Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) models to translate in vitro efficacy/toxicity into clinical exposure predictions [17] [18].

The workflow below illustrates this integrated approach.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My NAM is working perfectly in-house, but other labs can't reproduce my findings. What should I focus on? A1: Reproducibility issues often stem from a lack of standardized protocols. Focus on defining a precise Context of Use and documenting every aspect of your protocol, including cell source, culture conditions, and assay readouts. Engaging with initiatives like the NIH's SOM Center, which aims to create standardized organoid models, can provide valuable guidelines and resources [17] [18].

Q2: For a new immunotherapy target with no animal model, what's the best NAM-driven strategy to gain regulatory approval for a first-in-human trial? A2: Build a compelling weight-of-evidence package using multiple human-relevant NAMs. This should include:

- In vitro functional data from immune-competent 3D models demonstrating the intended mechanism of action and preliminary efficacy [27].

- Integration with in silico models (PBPK/QSP) to predict human pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, informing first-in-human dosing [18].

- Leverage existing datasets (e.g., Human Protein Atlas) to validate target expression and safety profile in human tissues. The FDA has shown openness to such integrated approaches for justifying waivers for animal studies [17] [18].

Q3: How can I model complex systemic immune reactions, like a cytokine storm, in an in vitro system? A3: Use a human-based multi-organ-on-chip (multi-OoC) system that connects different tissue models (e.g., liver, immune, vascular) through microfluidic circulation. For example, an in vitro human liver chip integrated with immune cells can specifically evaluate and detect cytokine release syndrome far more accurately than non-human systems. These platforms are designed to replicate systemic immunological processes and can capture organ-organ crosstalk critical for such reactions [17] [2].

Q4: What are the biggest pitfalls when incorporating AI into my immunology NAM workflow, and how can I avoid them? A4: Key pitfalls include:

- Poor Quality Data: AI models are only as good as the data they're trained on. Ensure your NAM data is high-quality, well-annotated, and biologically relevant [28].

- Lack of Interpretability ("Black Box"): Regulators and scientists need to understand the AI's reasoning. Use methods like Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) to integrate external knowledge sources and improve factual accuracy, or prioritize models that provide explanatory insights [29].

- Algorithmic Bias: Be aware that AI can inherit biases from its training data. Actively work to include diverse biological data (e.g., from donors of different ages, sexes, and ethnicities) to make your models more generalizable and equitable [27].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantifying the Translational Gap in Immunology Models

This table summarizes the documented limitations of traditional animal models and the corresponding capabilities of advanced NAMs.

| Challenge Area | Documented Limitation in Animal Models | NAM Capability & Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Predictive Safety | Over 90% of drugs appearing safe in animals fail in human trials due to safety/effi cacy issues [17]. TGN1412 caused cytokine storm in humans after being safe in monkeys [17] [18]. | Human in vitro liver models with immune cells can better predict cytokine release syndrome [17]. |

| Species Specificity | Ipilimumab showed minimal safety concerns in NHPs but has high irAE incidence in humans. Pembrolizumab raised safety concerns in NHPs but has a favorable human profile [18]. | Use of human 3D immune-competent models (e.g., organoids) captures human-specific biology and cell responses [26] [27]. |

| Modeling Human Diversity | Animal models are often inbred, single-sex, and kept in sterile environments, failing to capture human population diversity [27]. | Biobanks of tissue from diverse donors (age, sex, ethnicity) used to create immune organoids preserve donor-specific immune responses [27]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Immune NAMs

Essential materials and tools for developing and analyzing sophisticated immunological New Approach Methodologies.

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Immune NAMs | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Human Immune Cells (e.g., PBMCs, T cells, macrophages) | Provide a genetically and functionally diverse, human-relevant source of immune components for co-culture models [26] [2]. | Source from diverse donors to capture population variability. Use fresh or properly cryopreserved cells to maintain viability and function. |

| 3D Scaffolds & Matrices (e.g., MatriDerm, collagen-elastin) | Provide the structural and biochemical foundation for 3D tissue models (e.g., full-thickness skin, organoids) that support immune cell integration and function [2]. | Choose a matrix that supports cell viability, infiltration, and mimics the native tissue environment. |

| Flow Cytometry Panels (e.g., 24+ color panels) | Enable high-throughput, multiparametric immunophenotyping of complex co-cultures to identify multiple cell types and their activation states simultaneously [2]. | Panel design is critical. Requires careful fluorochrome selection and compensation controls to ensure data quality. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Kits | Allow for mapping of gene expression within the context of tissue architecture in a NAM, revealing localized immune responses [25]. | Integration with histopathology images via AI can predict gene expression patterns, maximizing data from a single sample [25]. |

| AI/ML Modeling Platforms | Analyze high-dimensional NAM data (transcriptomics, imaging), predict immune responses, and generate hypotheses by integrating diverse datasets [28] [18] [29]. | Model interpretability and validation with robust biological datasets are essential for regulatory acceptance and scientific insight [29]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a Microfluidic Platform for Modeling Vascular Inflammation

This protocol, based on the work of Ehlers et al., enables real-time measurement of endothelial barrier function and immune cell migration in a high-throughput manner [2].

1. System Setup:

- Utilize a 64-channel parallel microfluidic platform.

- Seed human endothelial cells (e.g., HUVECs) into the microfluidic channels and culture until a confluent monolayer is formed. Monitor confluence and barrier integrity via Transendothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER).

2. Inflammation Induction & Immune Cell Recruitment:

- Introduce a pro-inflammatory cytokine (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β) into the channels to activate the endothelium.

- In parallel, isolate primary human immune cells (e.g., PBMCs or monocytes) from blood and label them with a fluorescent cell tracker dye.

3. Real-Time Analysis:

- TEER Measurement: Continuously monitor TEER values across all channels to quantify the breakdown of the endothelial barrier in response to inflammation.

- Immune Cell Migration Assay: Perfuse the fluorescently labeled immune cells through the channels. Use live-cell imaging to track their adhesion to and migration through the endothelial layer.

- Endpoint Immunostaining: Fix the cells and stain for adhesion molecules (e.g., ICAM-1, VCAM-1) to confirm endothelial activation.

Protocol 2: Functional Assessment of a Peptide-Based Vaccine Candidate Using Dendritic Cells

This in vitro protocol, adapted from Lu et al., provides a method to screen vaccine immunogenicity before moving to animal studies [2].

1. Dendritic Cell Culture & Antigen Exposure:

- Culture the DC2.4 dendritic cell line or generate dendritic cells from primary human or mouse bone marrow precursors.

- Expose the dendritic cells to the peptide-based vaccine candidate. Include a known immunogenic peptide as a positive control and an untreated group as a negative control.

2. Measurement of Dendritic Cell Activation:

- Uptake Assay: Use a fluorescently tagged version of the peptide and measure internalization via flow cytometry or confocal microscopy after a set incubation period.

- Maturation Marker Analysis: After 24-48 hours, harvest cells and stain for surface maturation markers (e.g., CD80, CD86, MHC-II). Analyze using flow cytometry.

- Cytokine Secretion: Collect cell culture supernatant and measure the concentration of key cytokines (e.g., IL-12) using an ELISA kit.

3. T Cell Activation Assay:

- Co-culture the peptide-pulsed dendritic cells with naïve T cells isolated from a compatible donor.

- After several days, measure T cell proliferation (e.g., via CFSE dilution) and activation (e.g., via CD69 expression or IFN-γ release).

Next-Generation Tools: A Practical Guide to NAM Technologies for Immune System Modeling

The field of immunology is undergoing a transformative shift, moving away from traditional animal models toward more human-relevant New Approach Methodologies (NAMs). Microphysiological systems (MPS), commonly known as Organ-on-Chip (OoC) technology, represent a pivotal advancement in this transition. These microfluidic devices contain engineered or natural miniature tissues designed to replicate the functional units of human organs, providing unprecedented control over cellular microenvironments and enabling the maintenance of tissue-specific functions [30].

The incorporation of immune components is critical for bringing OoC models to the next level and enabling them to mimic complex biological responses to infection, disease, and therapeutic interventions [31]. As the scientific community acknowledges the limitations of animal models—including poor translatability to humans, low reproducibility rates, high costs, and ethical concerns—MPS offer a promising alternative that bridges the gap between conventional cell cultures and human physiology [32]. This technical resource center provides practical guidance for researchers navigating the implementation of immunocompetent MPS, with a specific focus on modeling immune cell recruitment and inflammatory processes.

Technical Support Center: FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I use MPS instead of well-established animal models for immunology research? MPS offer several advantages for immunology research: they provide human-relevant data that often translates better to clinical outcomes than animal studies; they enable precise control over the cellular microenvironment; they allow for real-time, high-resolution imaging of immune processes; and they align with regulatory shifts toward NAMs. Notably, around 90% of drug trials pre-screened in animals fail in humans due to differences in drug efficacy and toxicity, highlighting the translational gap that MPS aim to bridge [32].

Q2: What are the key considerations when designing an MPS model to study immune cell recruitment? Successful modeling of immune cell recruitment requires recreating the multi-step extravasation cascade. Key considerations include: (1) Incorporating a functional endothelial barrier that expresses appropriate adhesion molecules (e.g., E-selectin, P-selectin, ICAM-1, VCAM-1); (2) Establishing a stable chemotactic gradient of cytokines or chemoattractants; (3) Applying physiological flow conditions to mediate cell rolling and adhesion; and (4) Including a 3D hydrogel-based extracellular matrix (ECM) to model the interstitial space through which immune cells migrate after transmigration [31].

Q3: Which immune cells are most commonly integrated into MPS, and what are the associated challenges? Innate immune cells (neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages) are most frequently integrated due to their central role in initial inflammatory responses and less complex activation requirements. Integrating adaptive immune cells (T cells, B cells) is more challenging because it often requires HLA-matching of all cell types in the system to prevent graft-versus-host-like reactions, which presents a significant cell-sourcing limitation [32].

Q4: My immune cells are not transmigrating effectively. What could be wrong? Ineffective transmigration can stem from several factors. Review the activation status of your endothelium—ensure it is properly activated with cytokines like TNF-α or IL-1β to upregulate adhesion molecules. Verify the integrity and stability of your chemokine gradient. Check the physiological relevance of your flow rates, as excessive shear stress can prevent cell arrest and adhesion. Finally, assess the composition and density of your hydrogel ECM, as an overly dense matrix can physically impede cell migration [31] [32].

Q5: Are there commercially available MPS platforms that support immunology research? Yes, several commercial platforms are widely used. The Emulate system (including Zoë-CM2 and the new AVA Emulation System) and the Mimetas OrganoPlate are both popular choices cited in recent research. The CN Bio PhysioMimix system is another validated platform. These systems offer various features, such as perfusion, imaging compatibility, and multi-organ capabilities, which can be leveraged for immune-focused studies [33] [34] [32].

Q6: What does the recent regulatory shift mean for my use of MPS in preclinical work? Recent regulatory changes significantly bolster the value of MPS data. The FDA Modernization Act 2.0 (2022) removed the mandatory requirement for animal testing for new drugs and explicitly recognized MPS as valid nonclinical test models. Furthermore, the FDA's 2025 roadmap outlines a plan to phase out routine animal testing, and the NIH now prioritizes funding for research that incorporates human-relevant methods like MPS. This means data from qualified MPS are not just acceptable but are increasingly expected by regulators [9].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

The table below outlines common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions when working with immunocompetent MPS.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Immunocompetent MPS Experiments

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Immune Cell Recruitment | - Insufficient endothelial activation.- Unstable or weak chemotactic gradient.- Non-physiological flow rate (too high). | - Characterize expression of adhesion molecules (e.g., ICAM-1, VCAM-1) on endothelium after cytokine stimulation.- Use hydrogels or controlled perfusion to maintain gradient stability. Validate with dye tests.- Optimize flow rate to allow for immune cell rolling and arrest; typical venous shear stresses range from 0.5 to 5 dyne/cm² [31] [32]. |

| Loss of Tissue Barrier Integrity | - High shear stress damaging the cell layer.- Cytokine-induced barrier disruption.- Incorrect cell seeding density. | - Measure Transepithelial/Transendothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) regularly to monitor barrier health.- Use perfusion systems that allow for ramping up flow gradually after barrier formation.- Perform functional permeability assays (e.g., with fluorescent dextran) to quantify integrity [35] [32]. |

| Low Viability of Primary Immune Cells | - Lack of necessary survival signals in media.- Shear-induced activation or damage.- Interaction with incompatible cell types (for adaptive cells). | - Supplement media with appropriate cytokines (e.g., GM-CSF for monocytes).- Introduce immune cells under low-flow or static conditions initially.- For T cell studies, use HLA-matched cell types from a single donor or iPSC source to prevent alloreactivity [32]. |

| High Background in Apical/Basal Sampling | - Cross-contamination between channels.- Non-specific binding to chip materials (e.g., PDMS). | - Verify the integrity of the separating membrane before seeding cells.- Pre-treat channels with blocking agents like BSA. Consider using non-PDMS, low-binding chips (e.g., Emulate's Chip-R1) for analyte collection [34]. |

| Difficulty Reproducing Complex Inflammation | - Lack of key resident immune cells (e.g., macrophages).- Failure to recapitulate tissue-specific pathophysiology. | - Pre-seed tissue-resident immune cells during the initial model establishment.- Incorporate patient-derived or disease-specific cells (e.g., from organoids) to build a more physiologically relevant model [35] [34]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Establishing a Basic Immune Cell Recruitment Assay

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating a simplified MPS model to study immune cell transmigration across an endothelial barrier, a foundational process in inflammation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Immune Cell Recruitment Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic Chip | Provides the scaffold with micro-channels for fluid flow and cell culture. Often features a porous membrane to separate compartments. | Mimetas OrganoPlate (3-lane channel), Emulate Chip-S1 [32]. |

| Endothelial Cells | Forms the vascular barrier that regulates immune cell transit. | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs), Primary Human Microvascular Endothelial Cells (HMVECs). |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Hydrogel | Mimics the interstitial tissue space and basement membrane. Provides structural support and biochemical cues for cell migration. | Collagen I, Matrigel, Fibrin, or composite hydrogels [31] [35]. |

| Chemoattractant | Creates a chemical gradient that directs immune cell migration. | Chemokines (e.g., IL-8, CCL2, CXCL12), bacterial peptide (fMLP), or complement component (C5a). |

| Cytokine for Activation | Activates the endothelium to upregulate adhesion molecules. | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) or Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), typically used at 1-100 ng/mL. |

| Immune Cells | The circulating cells being studied for recruitment. | Primary human neutrophils, monocytes, or conditionally immortalized cell lines. |

Workflow Steps:

- Chip Preparation and ECM Coating: Sterilize the chip (e.g., UV light). Prepare the ECM solution (e.g., collagen I) on ice and introduce it into the designated tissue or ECM channel. Allow it to polymerize at 37°C for 30-60 minutes [35].

- Endothelial Barrier Seeding: Trypsinize and resuspend endothelial cells at a high density (e.g., 10-20 million cells/mL). Seed the cell suspension into the vascular (bottom) channel. Let the cells adhere under static conditions for a period (e.g., 1-2 hours) before initiating a low flow to remove non-adherent cells.

- Barrier Maturation: Culture the chip under continuous perfusion with endothelial growth medium for 2-4 days to form a confluent, tight monolayer. Monitor barrier integrity via TEER or permeability assays if possible.

- Endothelial Activation: Introduce a pro-inflammatory cytokine (e.g., TNF-α at 10 ng/mL) into the vascular channel via the perfusion medium. Incubate for 4-24 hours to activate the endothelium and induce adhesion molecule expression.

- Establishing a Chemotactic Gradient: After activation, introduce a chemoattractant into the tissue compartment (opposite side of the membrane from the endothelium) or into the ECM hydrogel. This establishes a concentration gradient that will guide the immune cells.

- Immune Cell Introduction and Assay: Resuspend fluorescently labeled immune cells in cell culture medium without serum. Introduce the immune cell suspension into the vascular channel under a defined, physiological flow rate. Allow cells to interact with the endothelium for the desired timeframe.

- Imaging and Analysis: Fix the cells at the endpoint and stain for actin (e.g., Phalloidin), nuclei (e.g., Hoechst), and specific markers (e.g., CD45 for leukocytes). Use confocal microscopy to capture z-stacks. Quantify the number of adhered and transmigrated cells using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ/Fiji) [31] [35].

The following diagram visualizes the core experimental setup and the biological process being modeled.

Visualizing the Immune Cell Extravasation Cascade

The process of immune cell migration from the vasculature into tissues, known as the extravasation cascade, is a multi-step process that can be effectively modeled in MPS. The following diagram details these key steps, which your MPS setup aims to replicate.

The Regulatory and Commercial Landscape for MPS

The drive to adopt MPS is strongly supported by a shifting regulatory and commercial environment. As noted in the troubleshooting section, the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 was a landmark change, legally recognizing MPS as valid tools for drug development [9]. This has been followed by concrete actions:

- The FDA's ISTAND pilot program accepted its first Organ-on-a-Chip (a Liver-Chip for predicting drug-induced liver injury) in September 2024, creating a formal pathway for qualifying these systems [9] [34].

- In April 2025, the FDA released a roadmap outlining a phased plan to reduce and eventually replace routine animal testing, prioritizing MPS data and AI-driven models [9].

- The NIH has shifted its funding priorities to favor grants that incorporate human-based technologies, and as of July 2025, it no longer funds proposals that rely exclusively on animal data [9] [36].

Commercially, the market offers robust platforms that simplify adoption. The Emulate AVA Emulation System launched in 2025 as a high-throughput 3-in-1 platform for running 96 chips in parallel, significantly expanding experimental scale [34]. CN Bio's PhysioMimix system is noted for its ease of use, PDMS-free consumables, and validated performance in single- and multi-organ configurations [33]. These advancements lower the barrier to entry, allowing researchers to focus on biology rather than device fabrication. When selecting a platform, consider factors such as throughput needs, compatibility with your desired readouts (e.g., imaging, -omics), and availability of validated protocols for your organ system of interest.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

Core Concepts and Applications

Q1: How do PBPK modeling and Agent-Based Models (ABMs) directly contribute to the reduction of animal models in immunology research?

These in silico approaches create virtual populations and simulate complex biological interactions, reducing the need for animal studies. Their specific contributions are outlined in the table below.

| Method | Primary Contribution to Animal Model Reduction | Key Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| PBPK Modeling [37] [38] [39] | Predicts drug/vaccine pharmacokinetics (PK) in diverse human populations (pediatric, geriatric, pregnant) where animal data translation is poor and clinical trials are ethically challenging. | Simulating drug exposure in pediatric populations, avoiding unnecessary clinical trials or extensive animal testing in these sensitive groups [37] [39]. |

| Agent-Based Models (ABMs) [40] | Simulates complex, emergent interactions within the immune system (e.g., between cells, cytokines, antigens) to predict immunogenicity and efficacy, which is difficult to model in animals. | Predicting the immunogenicity of biological compounds and vaccines, such as simulating infection dynamics and host immune system interactions for COVID-19 [40]. |

| AI/ML Integration [41] [42] [43] | Analyzes large multimodal datasets to predict immune responses, toxicity, and identify vaccine targets, slashing the time and cost of preclinical animal research. | Using tools like AlphaFold for de novo vaccine antigen discovery and predicting biomolecular interactions to accelerate immunotherapeutic design [41]. |

Q2: What are the most common technical challenges and solutions when integrating PBPK models with AI for immunogenicity prediction?

Integrating PBPK with AI, while powerful, presents specific technical hurdles. The table below details common issues and recommended solutions.

| Technical Challenge | Underlying Cause | Troubleshooting & Solution Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Uncertainty & Large Parameter Space [43] | PBPK models for complex entities like antibodies or nanoparticles require many parameters (e.g., blood flow, enzyme expression, binding constants) that are often unknown or vary widely. | Use AI/ML for parameter estimation and to reduce the complexity of the parameter space. Perform sensitivity analyses to identify the most critical parameters requiring precise estimation [43]. |

| Limited Data Availability [43] | A lack of high-quality, tissue-specific drug concentration data or human-relevant in vitro data for training AI models limits predictive accuracy. | Leverage AI to mine existing datasets and integrate Real-World Data (RWD). Use QSAR models informed by AI to predict parameters from a drug's physicochemical properties where data is scarce [37] [43]. |

| Model Validation & Regulatory Acceptance [44] | Concerns about the credibility of integrated models for regulatory decision-making beyond established areas like drug-drug interactions. | Adopt a "predict-learn-confirm" cycle. Follow regulatory guidance (e.g., FDA credibility assessment framework) and engage early with agencies like the EMA and FDA to align on model development and validation standards [39] [44]. |

Q3: What steps can be taken to validate an Agent-Based Model for vaccine immune response prediction when human data is scarce?

When human data is limited, a multi-faceted validation strategy is required.

- Utilize the Universal Immune System Simulator (UISS): Employ established platforms like UISS, which have been successfully applied to model various diseases and immune responses. Using a validated framework provides a solid foundation [40].

- Leverage All Available Preclinical Data: Calibrate and validate the ABM using high-quality, well-designed animal study data. Ensure the animal studies incorporate randomization, blinding, and proper power calculations to improve data reliability and translational value [41].

- Incorporate Human In Vitro Data: Integrate data from human-relevant New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) such as organoids or organs-on-chips. These systems provide direct human biological data for validating specific model components [12] [8].

- Perform Virtual Population Studies: Run the model across a wide range of virtual patients to ensure it can reproduce known population-level immunological outcomes and behaviors, even if individual-level data is missing [37].

Technical Troubleshooting

Q4: Our PBPK model predictions for a nanoparticle-based vaccine in geriatric populations do not match initial clinical data. What could be wrong?

This discrepancy often arises from failing to account for key physiological and biological changes in the elderly. Focus on these parameters:

- Verify Physiological Parameters: Ensure the virtual population accurately reflects age-dependent decreases in hepatic and renal function, which can impair clearance and prolong half-life [37].

- Check for Disease-Associated Changes: The geriatric population often has comorbidities. Confirm if the model accounts for specific disease states that may alter organ function or volume [38].

- Review Nanoparticle-Specific Processes: For nanoparticles, key processes like uptake by the mononuclear phagocytic system can show high inter-patient variability. Ensure your model's parameters for these processes are calibrated for age-related changes in immune function [43].

- Conduct Sensitivity Analysis: Perform a sensitivity analysis on all parameters related to geriatric physiology and nanoparticle disposition to identify which have the largest impact on your model's output and require refinement [39] [43].

Q5: An AI model trained on existing datasets for T-cell epitope prediction is performing poorly for a novel pathogen. How can this be addressed?

This is typically a problem of data bias or model applicability.

- Retrain with Pathogen-Specific Data: Fine-tune the model using any available, even if limited, experimental data specific to the novel pathogen. This helps the model adapt to the new biological context [41].

- Explore Alternative AI Architectures: If the current model is consistently wrong, consider using a different AI approach. For instance, for predicting protein-antibody complexes, tools like ZDOCK may sometimes provide more accurate docking orientation predictions than AlphaFold 3, which might not capture dynamic conformational changes during binding [41].

- Augment Training Data: Use data augmentation techniques or integrate multi-omics data (genomics, proteomics) to broaden the model's feature set and improve its generalizability [41] [8].

- Validate with In Vitro Models: Use patient-derived organoids or other NAMs to generate human-relevant data for key predictions, creating a feedback loop to retrain and improve the AI model [12] [8].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents, software, and technologies essential for implementing the in silico and AI-driven approaches discussed.

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function in NAMs Research |

|---|---|---|

| GastroPlus [40] | PBPK Software Platform | Simulates and predicts the pharmacokinetics of drugs and formulations in various human populations. |