Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Methods in Computational Immunology: From Algorithms to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of machine learning (ML) methods revolutionizing computational immunology.

Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Methods in Computational Immunology: From Algorithms to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of machine learning (ML) methods revolutionizing computational immunology. It explores the foundational principles underpinning the shift from traditional methods to AI-driven approaches, including deep learning and generative models. The review systematically compares methodological frameworks for specific applications like therapeutic antibody design, vaccine development, and multiscale immune profiling. It addresses critical challenges in data integration, model optimization, and validation, while evaluating performance benchmarks across different computational strategies. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this analysis synthesizes current capabilities, limitations, and future trajectories of ML in accelerating immunology research and therapeutic discovery.

The Computational Immunology Revolution: From Biological Principles to AI-Driven Discovery

The fields of immunology and data science are undergoing a profound integration, forging a new computational paradigm that is reshaping how we understand immune function and develop therapeutics. This convergence is driven by the exponential growth of high-throughput biological data, from single-cell omics to immune repertoire sequencing, which requires sophisticated computational approaches for meaningful interpretation [1] [2]. The emerging discipline of computational immunology leverages machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) to decipher the incredible complexity of immune systems across multiple scales—from molecular interactions to organism-level responses.

This transformation is particularly evident in personalized cancer immunotherapy, where the identification of tumor-specific antigens has been revolutionized by computational methods [3] [4]. Similarly, in clinical applications like postoperative rehabilitation prognosis, hybrid computational intelligence algorithms now achieve remarkable classification accuracy with minimal training data [5]. As these computational approaches mature, rigorous comparative analysis becomes essential for benchmarking performance and guiding methodological selection. This review provides a systematic comparison of computational immunology methods, evaluating their performance across key applications to establish evidence-based guidelines for researchers and clinicians navigating this rapidly evolving landscape.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Methods

Performance Benchmarking Across Applications

Table 1: Performance comparison of computational methods in immunology applications

| Application Domain | Method Category | Specific Methods | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rehabilitation Prognosis | Hybrid CI Algorithms | GAKmeans, GAClust, GAKNN | 100% accuracy with 35-90% training data | [5] |

| Tumor Antigen Prediction | Traditional ML | SVM, Random Forest | Varies by dataset and features | [4] |

| Tumor Antigen Prediction | Ensemble Learning | PSRTTCA, StackTTCA | Superior to traditional ML | [4] |

| Expression Forecasting | Multiple ML Methods | Various | Rarely outperforms simple baselines | [6] |

| Single-cell Analysis | Foundation Models | scBERT, Geneformer | Enhanced cell type classification | [1] |

Table 2: Methodological characteristics and implementation considerations

| Method Type | Representative Algorithms | Strengths | Limitations | Implementation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ML | KNN, K-means, SVM, Random Forest | Interpretability, computational efficiency | Limited with complex nonlinear data | Standard computing resources |

| Deep Learning | Autoencoders, CNNs, GNNs | Automatic feature extraction, handles complexity | High computational demand, data hunger | GPU acceleration, large datasets |

| Ensemble Methods | Stacking, Hybrid frameworks | Improved accuracy, robustness | Complex implementation and tuning | Multiple algorithms, integration |

| Foundation Models | scGPT, Geneformer | Transfer learning, multi-task capability | Extensive pretraining required | Massive datasets, specialized expertise |

The performance data reveals significant variation across computational immunology applications. In rehabilitation classification for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty patients, hybrid computational intelligence algorithms demonstrated exceptional efficiency, achieving 100% classification accuracy on test sets while using only 35-53.3% of available data for training [5]. This represents a substantial improvement over traditional machine learning approaches like K-nearest neighbors, which required 80% of data for training to achieve similar performance.

For tumor T-cell antigen identification, ensemble learning methods consistently outperform traditional single-algorithm approaches. Methods like StackTTCA and PSRTTCA, which integrate multiple models into hybrid frameworks, show superior predictive accuracy compared to support vector machines or random forests alone [4]. This advantage stems from the ability of ensemble methods to capture complementary patterns from diverse feature representations.

Unexpectedly, in expression forecasting—predicting gene expression changes following genetic perturbations—a comprehensive benchmarking study found that most machine learning methods rarely outperform simple baselines [6]. This highlights the importance of rigorous benchmarking, as methodological sophistication does not always guarantee superior performance in biological applications.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Rehabilitation Prognosis Protocol

The experimental protocol for rehabilitation classification and prognosis involved a two-phase approach using data from 120 patients who underwent reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Each patient case included 17 features encompassing demographic information, preoperative and postoperative passive range of motion measurements, visual analog pain scale scores, and total rehabilitation time [5].

In Phase I, researchers applied K-nearest neighbors (KNN), K-means clustering, and a genetic algorithm-based clustering algorithm (GAClust). The dataset was divided into training and test sets, with algorithms trained to classify patients based on total recovery time (dichotomized at 4.5 months). Performance was evaluated using classification accuracy: (true positives + true negatives) / total cases [5].

Phase II introduced hybrid computational intelligence algorithms including GAKNN (Genetic Algorithm K-nearest neighbors), GAKmeans, and GA2Clust. These algorithms incorporated genetic algorithm optimization to identify the minimal training set required for maximum classification performance. The genetic algorithm evolved optimal training set compositions through selection, crossover, and mutation operations, evaluating fitness based on classification accuracy on the test set [5].

Tumor Antigen Prediction Framework

The standard framework for developing machine learning-based tumor T-cell antigen predictors involves six major steps [4]:

- Dataset Construction: Curating high-quality benchmark datasets from literature and databases, with separation into training and independent test sets.

- Feature Encoding: Transforming peptide sequences into numerical descriptors using various encoding schemes (e.g., physicochemical properties, sequence composition).

- Feature Selection: Identifying and retaining the most discriminative features to reduce dimensionality and minimize noise.

- Algorithm Selection: Choosing appropriate machine learning models (e.g., SVM, random forest) or developing ensemble methods.

- Model Training: Optimizing model parameters typically using k-fold cross-validation on the training set.

- Performance Evaluation: Assessing model generalization on independent test datasets using metrics like accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.

This structured approach ensures rigorous development and evaluation of predictive models for tumor antigen identification.

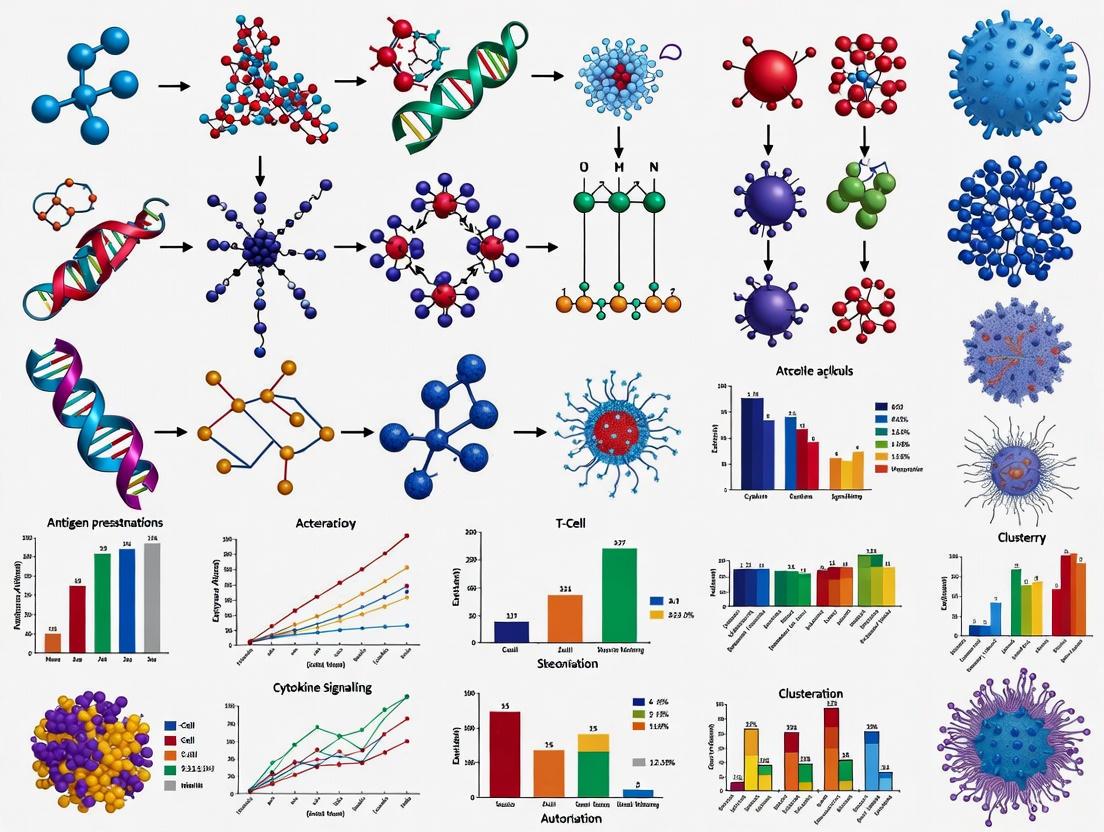

Visualization of Computational Workflows

Methodological Approach for Rehabilitation Classification

Tumor Antigen Prediction Pipeline

Table 3: Key computational tools and resources in immunology research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-cell Analysis | Seurat, Scanpy | Normalization, clustering, visualization | Single-cell RNA sequencing data |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | scVI, Autoencoders | Dimensionality reduction, integration | Multi-omics data integration |

| Foundation Models | scBERT, Geneformer, scGPT | Transfer learning, prediction | Cell type classification, perturbation |

| Immunoinformatics Tools | NetMHC, MHC-Nuggets | Antigen presentation prediction | Neoantigen discovery [3] |

| Benchmarking Platforms | CZI Virtual Cells | Standardized model evaluation | Cross-domain ML benchmarking [7] |

The computational immunology toolkit encompasses diverse resources essential for modern immunological research. For single-cell omics analysis, Seurat (R-based) and Scanpy (Python-based) provide comprehensive workflows for normalization, highly variable gene selection, dimensionality reduction, and clustering [1]. These platforms employ graph-based approaches to quantify cell similarities, enabling the identification of distinct cell populations and states within complex immunological datasets.

Deep learning frameworks like scVI (Single-cell Variational Inference) utilize variational autoencoders to learn probabilistic representations of gene expression data while accounting for technical artifacts such as batch effects [1]. These models are particularly valuable for integrating multimodal data, including RNA expression, surface protein measurements, and chromatin accessibility, projecting them into a unified latent space for downstream analysis.

Emerging foundation models represent a paradigm shift in computational immunology. Models like scBERT, Geneformer, and scGPT are trained on massive single-cell datasets using self-supervised learning, enabling them to be fine-tuned for diverse downstream tasks including cell type classification, gene expression prediction, and cross-modality integration [1]. These models demonstrate the transformative potential of transfer learning in immunology, potentially reducing the data requirements for specific applications.

For antigen-focused research, immunoinformatics tools support key steps in neoantigen prediction, including human leukocyte antigen typing, peptide-MHC presentation prediction, and T-cell recognition profiling [3]. These resources are integral to personalized cancer vaccine development and cancer immunotherapy design.

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The comparative analysis presented in this review reveals several key insights regarding the current state of computational immunology. First, method performance is highly context-dependent, with certain approaches demonstrating exceptional efficacy in specific applications but not others. The remarkable efficiency of hybrid genetic algorithm methods in rehabilitation prognosis [5] contrasts with the limited advantage of complex models in expression forecasting [6], highlighting the danger of one-size-fits-all methodological recommendations.

Second, the field faces significant benchmarking challenges that impede rigorous comparative evaluation. As noted in the CZI Virtual Cells Workshop outcomes, the lack of standardized, cross-domain benchmarks undermines the development of robust, trustworthy models [7]. Issues of data heterogeneity, reproducibility challenges, model biases, and fragmented resources collectively hamper systematic methodological progress. Future efforts should prioritize high-quality data curation, standardized tooling, comprehensive evaluation metrics, and open collaborative platforms to address these limitations.

The rapid emergence of foundation models in single-cell and spatial omics represents one of the most promising future directions [1]. These models, pretrained on massive datasets, can be fine-tuned for diverse downstream tasks with relatively small task-specific datasets. This approach mirrors the success of foundation models in natural language processing and computer vision, offering potential solutions to the data scarcity problems that plague many immunological applications.

Another critical frontier is the development of more sophisticated multi-scale models that integrate immunological data across molecular, cellular, tissue, and organism levels. Such integration is essential for capturing the true complexity of immune responses, which emerge from interactions across these scales. Recent advances in graph neural networks are particularly promising for this challenge, as they can naturally represent the complex interaction networks that characterize immune system organization and function [1] [8].

Finally, the successful integration of AI and immunology requires closer collaboration between computational scientists and immunologists. As noted in research on AI for vaccine development, AI models must balance complexity with interpretability and must be grounded in immunological principles to generate biologically meaningful insights [8]. The emerging field of "immuno-AI" aims to bridge this disciplinary divide, fostering interdisciplinary approaches that leverage the strengths of both computational and experimental immunology.

This comparative analysis of computational immunology methods demonstrates a dynamic and rapidly evolving field where methodological innovation is driving substantial advances in immunological understanding and clinical applications. The performance benchmarks presented reveal that while no single approach dominates across all applications, clear patterns emerge in specific domains—from the efficiency of hybrid algorithms in clinical prognosis to the superiority of ensemble methods in antigen prediction.

The ongoing convergence of immunology and data science is producing an increasingly sophisticated computational paradigm characterized by more powerful algorithms, more integrative multi-scale models, and more rigorous benchmarking practices. As foundation models and other advanced AI approaches gain traction, the field appears poised for transformative advances in how we understand, predict, and modulate immune function.

For researchers and clinicians navigating this complex landscape, the key principles emerging from this analysis are: (1) select methods based on rigorous domain-specific benchmarking rather than general algorithmic sophistication; (2) prioritize approaches that balance predictive power with biological interpretability; and (3) embrace interdisciplinary collaboration as essential for translating computational insights into immunological understanding and clinical impact. As computational immunology continues to mature, this integration of data-driven discovery and immunological expertise will be essential for realizing the full potential of this transformative convergence.

The field of computational immunology has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from traditional statistical methods to sophisticated machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) approaches. This shift is driven by the growing complexity of immunological data and the need to understand intricate immune system processes at multiple biological scales. Traditional statistical models, long the foundation of biological data analysis, are aimed at inferring relationships between variables to understand underlying biological mechanisms. In contrast, ML focuses on maximizing predictive accuracy by learning patterns from data itself, often without explicit programming of the rules [9]. This comparative analysis examines the performance of traditional computational methods against modern machine learning techniques within immunology research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with an objective assessment of their capabilities, experimental requirements, and optimal applications.

Historical Progression of Computational Methods in Immunology

Traditional Statistical Methods

The foundation of computational immunology was built upon traditional statistical approaches that provided mathematically rigorous frameworks for analyzing immune system data. Early computational models in immunology first emerged from humoral immunology roots, particularly in describing complement fixation and antibody-antigen interactions [10]. These initial models were essential for quantifying interactions that were previously only qualitatively described.

Key Traditional Methods and Their Applications:

- Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression: A fundamental statistical method for estimating parameters in linear regression models by minimizing the sum of squared residuals. OLS works best when its underlying assumptions are followed and produces easily interpretable coefficients that summarize the influence of each input feature [11].

- Complement Fixation Modeling: Early computational approaches modeled the sigmoidal relationship between complement concentration and hemolysis fraction, establishing quantitative frameworks for antibody-antigen interactions [10].

- Limiting Dilution Analysis: Used statistical models based on Poisson distribution to estimate antigen-responsive T-cell frequencies in peripheral blood mononuclear cells [10].

- Quantitative Immunoelectrophoresis: Enabled determination of relative antigen-antibody affinities through computational analysis of electrophoretic patterns [10].

Traditional statistical approaches excel when there is substantial a priori knowledge on the topic under study, when the set of input variables is limited and well-defined in current literature, and when the number of observations largely exceeds the number of input variables [9]. These methods produce "clinician-friendly" measures of association, such as odds ratios in logistic regression models or hazard ratios in Cox regression models, which allow researchers to easily understand underlying biological mechanisms [9].

The Machine Learning Revolution

The emergence of machine learning in immunology represents a paradigm shift from hypothesis-driven to data-driven discovery. ML explicitly considers the trade-offs associated with learning, such as the balance between prediction accuracy and model complexity, and the generalization of models to unseen data [11]. This transition became necessary as immunological datasets grew in size and complexity, particularly with the advent of high-throughput technologies like single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics.

ML encompasses a wide range of algorithms categorized into three main types: supervised learning (using labeled data), unsupervised learning (identifying structures in unlabeled data), and reinforcement learning (making decisions based on reward feedback) [11]. The key advantage of ML lies in its ability to analyze various data types - including imaging data, demographic data, and laboratory findings - and integrate them into predictions for disease risk, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment applications [9].

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Computational Method Adoption in Immunology

| Time Period | Dominant Computational Methods | Key Applications in Immunology | Data Types Analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1990s | Traditional statistical models (OLS, Poisson distribution) | Antibody-antigen kinetics, complement fixation, limiting dilution assays | Numerical measurements, concentration data |

| 1990s-2000s | Generalized linear models, basic computational simulations | Cellular cytotoxicity assays, T-cell frequency estimation, ELISA data analysis | Laboratory assay data, protein concentrations |

| 2000s-2010s | Early machine learning (SVMs, Random Forests) | HLA typing, epitope prediction, immune cell classification | Genomic data, protein sequences, flow cytometry |

| 2010s-Present | Deep learning, neural networks, ensemble methods | Spatial transcriptomics, vaccine design, patient stratification, personalized immunotherapies | Multi-omics data, histopathology images, scRNA-seq |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Recent studies have directly compared the performance of traditional statistical methods and machine learning approaches across various immunological applications. The results demonstrate context-dependent advantages for each approach.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Between Traditional and ML Methods in Immunology Research

| Method Category | Predictive Accuracy Range | Interpretability | Data Requirements | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Statistical Methods (OLS, Cox regression) | 70-85% (structured problems) | High | Small to medium datasets (n < p) | Low to moderate |

| Basic Machine Learning (Random Forest, SVM) | 85-95% (complex patterns) | Moderate | Medium to large datasets (n ≈ p or n > p) | Moderate |

| Deep Learning (CNN, BiLSTM) | 90-99% (image, sequence data) | Low | Very large datasets (n >> p) | Very high |

| Ensemble ML Methods (Weighted voting, stacking) | 95-100% (diverse data types) | Low to moderate | Large, multi-modal datasets | High |

In a recent IoT botnet detection study (methodologically relevant to immunological pattern recognition), researchers conducted a systematic comparison between traditional ML and deep learning approaches. The ensemble framework integrating Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM), Random Forest, and Logistic Regression via a weighted soft-voting mechanism achieved 100% accuracy on the BOT-IOT dataset, 99.2% on CICIOT2023, and 91.5% on IOT23, outperforming state-of-the-art models by up to 6.2% [12]. This demonstrates the power of combining multiple approaches for complex pattern recognition tasks.

The performance advantages of ML are particularly evident in "omics" applications, where numerous variables are involved with complex interactions. ML has proven more appropriate than traditional methods in genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, where traditional regression models show significant limitations, especially for choosing the most important risk factors from hundreds or thousands of potential candidates [9].

Autoimmune Disease Research Applications

In autoimmune disease research, ML approaches have demonstrated remarkable success in patient stratification and biomarker discovery. A recent autoimmune disease machine learning challenge attracted nearly 1,000 experts from 62 countries to develop models predicting gene expression from pathology images for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [13]. The winning approaches utilized foundational models trained on vast histopathology image datasets to derive meaningful representations and align single-cell gene expression with histopathology imaging data into shared representations [13].

High-performing models in this challenge commonly incorporated spatial arrangements of cells through positional encoding or self-attention techniques, significantly outperforming baseline traditional methods [13]. These approaches demonstrate how ML can integrate complex, multi-modal data types - a capability beyond most traditional statistical methods.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Traditional Statistical Workflows

Traditional statistical analysis in immunology follows a structured, hypothesis-driven workflow with clearly defined steps:

Protocol 1: Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression for Immunological Data

- Data Collection and Preparation: Gather experimental measurements with n observations and p variables, ensuring n > p. Variables should be continuous and normally distributed.

- Model Specification: Define the linear relationship: yi = α + βxi + εi, where yi represents the dependent variable (e.g., antibody concentration), xi represents independent variables (e.g., antigen dose, time), α is the intercept, β represents coefficients, and εi is the error term.

- Parameter Estimation: Calculate coefficient estimates that minimize the sum of squared residuals: β = Σ(xi - x̄)(yi - ȳ) / Σ(xi - x̄)2 and α = ȳ - βx̄.

- Assumption Verification: Test for linearity, homoscedasticity, independence, and normality of residuals.

- Inference and Interpretation: Evaluate coefficient significance using t-tests and compute confidence intervals. Interpret β values as the change in y per unit change in x.

This OLS approach works best when its underlying assumptions are met but has extensions for various situations, such as using absolute error to reduce outlier impact or incorporating prior knowledge through Bayesian methods [11].

Modern Machine Learning Pipelines

ML experimental protocols emphasize iterative optimization and validation:

Protocol 2: Ensemble ML Framework for Immunological Pattern Recognition

Data Preprocessing:

- Handle missing values through imputation or removal

- Apply Quantile Uniform transformation to reduce feature skewness while preserving attack signatures (achieving near-zero skewness: 0.0003 vs. 1.8642 for log transformation) [12]

- Address class imbalance using SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique)

Multi-Layered Feature Selection:

- Perform correlation analysis to remove highly redundant features

- Apply Chi-square statistics with p-value validation

- Conduct distribution analysis across label classes using advanced proportional analysis techniques

Model Training and Optimization:

- Implement cross-validation with dataset-specific strategies (5-10 folds depending on data size)

- Train multiple model types: CNN with optimized layers, BiLSTM with tuned memory units, Random Forest with optimized tree depth, and Logistic Regression with regularization

- Balance underfitting and overfitting using threshold-based decision-making

Ensemble Integration:

- Combine predictions through weighted soft-voting mechanisms

- Assign weights based on individual model performance metrics

- Generate final predictions through consensus approach

Validation and Interpretation:

- Evaluate using comprehensive metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, AUC-ROC)

- Perform error analysis to identify systematic failure modes

- Apply model interpretation techniques (SHAP, LIME) for biological insights

This structured approach enabled the ensemble framework to achieve exceptional performance across diverse datasets [12].

Visualization of Methodologies

Traditional Statistical Analysis Workflow

Machine Learning Analysis Workflow

Ensemble Method Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Computational Immunology

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Research | Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Analysis | R, SAS, SPSS, STATA | Implementation of traditional statistical models (OLS, Cox regression) | Structured data, balanced designs |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch, XGBoost | Building and training ML models for prediction and classification | Large, complex datasets |

| Immunology-Specific Tools | ImmPort, VDJServer, ImmuneSpace | Domain-specific data management and analysis platforms | Immunological assay data |

| Data Integration Platforms | Galaxy, Cytoscape, KNIME | Multi-omics data integration and visualization | Heterogeneous data sources |

| Visualization Tools | ggplot2, Plotly, Scanpy, Seurat | Data exploration and result presentation | All data types |

| High-Performance Computing | AWS, Google Cloud, Azure | Handling computational demands of large-scale ML | Big data applications |

Discussion and Future Directions

The integration of AI and ML in computational immunology is anticipated to propel advances in precision medicine for autoimmune diseases and beyond [14]. However, challenges regarding data quality, model interpretability, and ethical considerations persist. The emerging field of immuno-AI aims to bridge the gap between computational and experimental immunology by fostering interdisciplinary collaboration between AI researchers and immunologists [8].

Future methodologies will likely leverage hybrid approaches that combine the interpretability of traditional statistical methods with the predictive power of machine learning. As noted in recent research, "Integration of the two approaches should be preferred over a unidirectional choice of either approach" [9]. This balanced perspective recognizes that traditional methods remain highly valuable when there is substantial a priori knowledge and well-defined variables, while ML excels in exploratory research with complex, high-dimensional data.

The successful application of these computational approaches will continue to transform immunology research, enabling more precise patient stratification, accelerated vaccine development, and novel immunotherapy design. As computational power increases and algorithms become more sophisticated, the boundary between traditional and machine learning methods may blur, leading to more integrated, powerful analytical frameworks for understanding the immune system in health and disease.

Core Immune System Challenges Addressed by Computational Approaches

The human immune system represents one of the most complex biological networks, comprising an estimated 1.8 trillion cells and utilizing approximately 4,000 distinct signaling molecules to coordinate protective responses [15]. This extraordinary complexity presents formidable challenges for researchers seeking to understand immune function, predict responses to pathogens, and develop targeted therapies. Computational immunology has emerged as a transformative discipline that leverages advanced algorithms, machine learning, and biophysical modeling to decipher immune system complexity. This guide provides a comparative analysis of computational methodologies addressing core challenges in immunology research, with specific applications for drug development professionals and research scientists.

Core Immune Challenges and Computational Solutions

Computational approaches have advanced to address specific, long-standing challenges in immunology. The table below summarizes major immune system challenges and the computational strategies developed to overcome them.

Table 1: Core Immune Challenges and Computational Solutions

| Immune System Challenge | Computational Approach | Key Methodologies | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCR-pMHC Recognition Complexity | AI-powered structural prediction | AlphaFold 3, RoseTTAFold, molecular docking | Cancer immunotherapy, vaccine design, autoimmune disease research [16] |

| Immune System Multi-scale Complexity | Systems Immunology | Network pharmacology, quantitative systems pharmacology, mechanistic models | Drug discovery, patient stratification, biomarker identification [15] |

| Integrating Multi-modal Data | Machine Learning Integrative Approaches | Variational autoencoders, graph neural networks, foundation models | Single-cell multi-omics analysis, cellular interaction mapping [17] [1] |

| Predicting Immunogenicity | Biophysical Representation Models | Free energy calculations, structural modeling, pocket field analysis | Antibody affinity optimization, epitope prediction, vaccine candidate screening [18] |

| Personalized Immune Forecasting | Immune Digital Twins | Multi-scale modeling, FAIR principles, AI-mechanistic model integration | Precision medicine, treatment optimization, clinical outcome prediction [19] |

Comparative Analysis of Computational Methodologies

AI-Driven Structural Prediction for TCR-pMHC Interactions

Experimental Protocol: The prediction of T-cell receptor-peptide-Major Histocompatibility Complex (TCR-pMHC) interactions follows a structured computational workflow. Researchers first select TCR and pMHC sequences from databases like IEDB or PDB. Using AlphaFold 3 with default hyperparameters (three recycling cycles, MSA depth of 256, template dropout rate of 15%), they generate 3D structural models of the ternary complex [16]. The models are evaluated using interface template modeling (ipTM) scores, with values >0.9 indicating high confidence predictions. Comparative analysis involves benchmarking against experimentally determined crystal structures through root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) calculations and binding interface analysis.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of TCR-pMHC Prediction Tools

| Tool | Methodology | Accuracy Metrics | Computational Demand | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 | Deep neural networks, attention mechanisms | ipTM >0.9 for peptide-bound complexes [16] | High (GPU-intensive) | Structural immunology, epitope discovery |

| NetTCR | Sequence-based machine learning | AUC 0.8-0.9 for specific epitopes [16] | Moderate | High-throughput epitope screening |

| ERGO | Deep learning on TCR sequences | Balanced accuracy ~70% [16] | Low-Moderate | TCR specificity prediction |

| Molecular Docking | Physics-based sampling/scoring | Success varies with system complexity | High | Binding affinity estimation |

Multi-omics Integration for Immune Profiling

Experimental Protocol: Single-cell multi-omics integration begins with sample processing through platforms like 10x Genomics, generating paired transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic data from the same cells. The computational workflow utilizes deep learning frameworks such as scVI (Single-cell Variational Inference) or scGPT, which learn probabilistic representations of the data while accounting for technical artifacts [1]. These models employ encoder-decoder architectures to project high-dimensional data into lower-dimensional latent spaces (typically 10-50 dimensions), enabling batch correction, cell state identification, and multi-modal integration. Validation includes benchmarking against known cell markers, clustering accuracy metrics, and trajectory inference consistency.

Table 3: Multi-omics Integration Platforms for Immunology Research

| Platform | Computational Architecture | Modalities Supported | Key Features | Immunology Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat | Graph-based, statistical | RNA, protein, chromatin | Canonical correlation analysis, mutual nearest neighbors | Immune cell atlas construction, host-response studies [1] |

| Scanpy | Python-based, graph algorithms | RNA, ATAC-seq, spatial data | Scalable to millions of cells, extensive visualization | Large-scale immune profiling studies [1] |

| scVI | Variational autoencoder | Multi-omics, perturbation data | Probabilistic modeling, batch correction | Rare immune population identification [1] |

| scGPT | Transformer foundation model | RNA, protein, cellular interactions | Transfer learning, in-silico perturbation prediction | Immune development trajectories, therapy response modeling [1] |

Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Immunology

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Computational Immunology

| Research Resource | Function/Purpose | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Immune Databases | Provide curated datasets for model training and validation | IEDB, SAbDab, ImmuneSpace, VDJPdb [18] [16] |

| Structure Prediction Tools | Generate 3D models of immune complexes | AlphaFold 3, RoseTTAFold, HADDOCK, PANDORA [18] [16] |

| Single-cell Analysis Suites | Process and integrate multi-omics data | Seurat, Scanpy, scVI, Scenic+ [1] |

| Biophysical Simulation Software | Model molecular interactions and dynamics | Free energy perturbation (FEP+) tools, molecular dynamics packages [18] |

| ML Frameworks | Develop and train custom models | TensorFlow, PyTorch, scikit-learn with biological extensions [17] [15] |

Visualization of Computational Immunology Workflows

Epitope Prediction and Vaccine Design Workflow

Multi-omics Immune Profiling Pipeline

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

The field of computational immunology faces several implementation challenges that must be addressed for broader clinical adoption. Data quality and standardization remain significant hurdles, as models require large, well-annotated datasets with representative biological variation [15] [19]. Model interpretability is crucial for clinical translation, with emerging Explainable AI (XAI) methods helping to bridge this gap [19]. Computational infrastructure demands are substantial, leading initiatives like the Ragon Institute's unified computing platform to address resource fragmentation across institutions [20]. Finally, regulatory considerations for clinical validation of computational models continue to evolve, particularly for AI/ML-based prognostic tools [15] [19].

The integration of computational approaches into immunology research has fundamentally transformed our ability to address the immune system's complexity. From AI-driven structural prediction to multi-omics integration and immune digital twins, these methodologies provide researchers with increasingly sophisticated tools to decipher immune function and dysfunction. As these technologies continue to mature, they promise to accelerate therapeutic development and enable more personalized approaches to treating immune-related diseases.

The field of computational immunology is being reshaped by an influx of high-throughput biological data. The integration of genomic, proteomic, single-cell, and clinical data provides a multi-layered view of the immune system, enabling researchers to decode its complexity at an unprecedented scale. Modern machine learning research thrives on these diverse, large-scale datasets to build predictive models and uncover novel biological insights. This guide offers a comparative analysis of these key data types, their sources, and the experimental methodologies that generate them, providing a foundational resource for researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of data science and immunology.

Genomic Data: From Sequencing to Variants

Genomic data forms the bedrock of genetic predisposition and variation studies in immunology. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized this field by making large-scale DNA and RNA sequencing faster, cheaper, and more accessible [21]. Unlike traditional Sanger sequencing, NGS enables simultaneous sequencing of millions of DNA fragments, democratizing genomic research and enabling high-impact projects like the 1000 Genomes Project and the UK Biobank [21].

Table 1: Key Genomic Data Types and Sources

| Data Type | Description | Primary Sources | Key Applications in Immunology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Read WGS | High-coverage sequencing of entire genome using short reads | All of Us Research Program, UK Biobank [21] [22] | Genome-wide association studies (GWAS), variant discovery across immune-related genes |

| Long-Read WGS | Sequencing with longer read lengths, better for complex regions | PacBio, Oxford Nanopore [21] [22] | Resolving HLA diversity, structural variations in immunogenomics |

| Microarray Genotyping | Array-based profiling of predefined variants | Illumina, Affymetrix [22] | Polygenic risk scores for autoimmune diseases, pharmacogenomics of immune therapies |

| CRAM/BAM Files | Compressed raw sequencing alignments | All of Us Program, sequencing cores [22] | Re-analysis of raw data, custom variant calling for immunology targets |

| Variant Call Format (VCF) | Standardized variant calling output | Joint calling pipelines, GATK workflows [22] | Sharing curated variant sets, clinical reporting of immune-related mutations |

Experimental Protocol: Whole Genome Sequencing for Immunogenomics

Methodology: The standard workflow for generating genomic data begins with DNA extraction from blood or tissue samples, followed by library preparation where DNA is fragmented and adapters are ligated. Sequencing is performed on platforms such as Illumina's NovaSeq X for high-throughput short-read data or Oxford Nanopore/PacBio for long-read sequencing, which is particularly valuable for resolving complex immune gene regions like the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) [21] [22]. The resulting reads are aligned to a reference genome (GRCh38), after which variant calling identifies single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions/deletions (indels), and structural variants. In computational immunology, special attention is given to genes involved in immune function, with annotation pipelines specifically designed for HLA and immunoglobulin loci.

Research Reagent Solutions for Genomics

Table 2: Essential Genomic Research Reagents and Platforms

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Key Providers |

|---|---|---|

| NovaSeq X Series | High-throughput sequencing | Illumina [21] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Long-read, real-time sequencing | Oxford Nanopore Technologies [21] |

| PacBio HiFi | High-fidelity long-read sequencing | Pacific Biosciences [22] |

| Somal_ogic SomaScan | Proteomic profiling via aptamers | Standard BioTools [23] |

| GATK | Genome analysis toolkit for variant discovery | Broad Institute [22] |

| Hail | Open-source framework for genomic data analysis | Hail Team [22] |

Proteomic Data: Mapping the Protein Landscape

Proteomics captures the dynamic protein events that genomics alone cannot reveal, including post-translational modifications, protein degradation, and cellular signaling events. While proteomics has historically lagged behind genomics in scale, rapid technological advances are narrowing this gap [23]. Proteomics is particularly valuable in immunology for characterizing cytokine profiles, signaling pathways, and immune cell surface markers.

Experimental Protocol: Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics

Methodology: Sample preparation begins with protein extraction from cells or tissues, followed by digestion into peptides using trypsin. The peptides are then separated by liquid chromatography and introduced into a mass spectrometer via electrospray ionization. Mass analysis is performed using instruments like Orbitrap or time-of-flight (TOF) mass analyzers, which measure the mass-to-charge ratios of peptide ions. Tandem MS (MS/MS) fragments selected peptides to generate sequence information. The resulting spectra are matched to theoretical spectra from protein databases using search engines like MaxQuant, enabling protein identification and quantification [23]. For immunological applications, special enrichment strategies may be employed to capture low-abundance cytokines or post-translationally modified signaling proteins.

Table 3: Proteomics Technologies and Applications

| Technology | Principle | Throughput | Key Applications in Immunology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry | Measures mass-to-charge ratios of peptides | Moderate to High | Comprehensive profiling of immune cell proteomes, signaling phosphoproteins |

| SomaScan | Aptamer-based protein capture and quantification | High (7,000+ proteins) | Biomarker discovery in serum/plasma, clinical trial monitoring [23] |

| Olink | Proximity extension assay for protein detection | High | Cytokine profiling, inflammatory biomarker validation [23] |

| Quantum-Si | Single-molecule protein sequencing | Low to Moderate | Antibody characterization, immune repertoire analysis [23] |

| Spatial Proteomics | Multiplexed antibody-based imaging in tissue | Moderate | Tumor microenvironment characterization, immune cell localization [23] |

Single-Cell Data: Resolving Cellular Heterogeneity

Single-cell technologies have transformed our understanding of immune cell heterogeneity, revealing rare cell populations and dynamic cell states within the immune system. The emergence of single-cell foundation models (scFMs) represents a significant advancement, applying transformer-based architectures to extract patterns from millions of single cells [24] [1].

Experimental Protocol: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

Methodology: The process begins with tissue dissociation or blood collection to create a single-cell suspension. Viable cells are then encapsulated into droplets or wells along with barcoded beads using platforms like 10x Genomics, BD Rhapsody, or Takara Bio. Within these partitions, cells are lysed, and mRNA molecules are captured and reverse-transcribed with cell-specific barcodes. The resulting cDNA libraries are amplified and prepared for sequencing, incorporating unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to account for amplification bias. After sequencing on platforms like Illumina, the data is processed through alignment, demultiplexing, and UMI counting to generate a digital gene expression matrix for each cell [24]. For immunology applications, this process is often combined with cell surface protein detection (CITE-seq) to simultaneously measure transcriptome and epitope profiles.

Table 4: Single-Cell Data Types and Analytical Approaches

| Data Type | Technology | Key Information | Computational Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq | 10x Genomics, Smart-seq2 | Gene expression per cell | Seurat, Scanpy, scVI [1] |

| CITE-seq | Oligo-tagged antibodies | Surface protein + gene expression | TotalVI, multimodal integration [1] |

| scATAC-seq | Transposase accessibility | Chromatin accessibility per cell | ArchR, Signac, Cicero |

| Single-cell Multiome | Simultaneous RNA+ATAC | Paired gene expression and chromatin | MOFA+, multiomic fusion |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Visium, MERFISH, Xenium | Gene expression in tissue context | Graph neural networks, spatial analysis [1] |

Single-Cell Foundation Models in Immunology

The field is rapidly evolving with the development of single-cell foundation models (scFMs) like scBERT, Geneformer, and scGPT, which are pretrained on massive single-cell datasets and can be fine-tuned for various downstream tasks [24] [1]. These models use transformer architectures to process single-cell data by treating cells as "sentences" and genes as "words," learning fundamental biological principles that generalize across tissues and conditions. For immunology, these models are particularly powerful for predicting cellular responses to perturbations, identifying novel immune cell states, and mapping differentiation trajectories of immune cells during development and disease [24].

Clinical Data: Bridging Research and Patient Care

Clinical data provides the essential link between molecular measurements and patient health outcomes, creating a critical bridge for translational immunology research. Clinical data encompasses multiple types, including electronic health records (EHRs), patient-generated health data (PGHD), disease registries, and administrative claims data [25] [26].

Table 5: Clinical Data Types and Research Applications

| Data Type | Sources | Key Variables | Immunology Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Health Records (EHR) | Hospital systems, clinics | Diagnoses, medications, lab results, procedures | Correlating immune markers with clinical outcomes, treatment response [25] |

| Patient-Generated Health Data (PGHD) | Wearables, mobile apps, patient surveys | Symptoms, quality of life, activity levels, vital signs | Monitoring autoimmune disease progression, treatment side effects [25] |

| Disease Registries | Specialty clinics, research networks | Disease-specific variables, treatment patterns, outcomes | Studying rare immune deficiencies, long-term outcomes of immunotherapies [26] |

| Administrative Claims | Insurance providers, payers | Billing codes, procedures, prescriptions | Population-level studies of immune-mediated disease epidemiology, healthcare utilization |

| Clinical Trial Data | Sponsor companies, research institutions | Protocol-specific endpoints, adverse events, biomarker data | Drug development, safety monitoring, biomarker validation [27] |

Experimental Protocol: Integrating Multi-Scale Data for Immunological Discovery

Methodology: The most powerful applications in computational immunology come from integrating multiple data types. A typical integrative analysis begins with cohort definition and patient selection from clinical databases or prospective recruitment. Molecular profiling (genomics, proteomics, single-cell assays) is performed on patient samples, while clinical data is extracted from EHRs and standardized using common data models like OMOP. Patient-reported outcomes may be collected through digital platforms. The various data types are then harmonized, with molecular features linked to clinical phenotypes. Machine learning approaches—including the risk-based methodologies advocated in recent FDA guidance—are applied to identify patterns predictive of disease progression, treatment response, or adverse events [27]. This integrated approach is particularly valuable for identifying biomarker signatures that stratify patients for targeted immunotherapies.

Comparative Analysis: Data Integration for Machine Learning in Immunology

The true power of modern computational immunology lies in the strategic combination of these data types. Each data modality provides a unique perspective on immune system function, and their integration enables a more comprehensive understanding than any single data type alone.

Table 6: Cross-Modal Data Integration Strategies

| Integration Approach | Data Types Combined | Computational Methods | Immunology Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical Integration | Genomic + Transcriptomic + Proteomic | Multi-omics factor analysis, MOFA+ | Mapping genetic variants to immune cell function through molecular intermediates |

| Horizontal Integration | Same data type across multiple cohorts, conditions | Batch correction, harmony, scVI | Identifying conserved immune cell states across diseases and populations |

| Temporal Integration | Longitudinal multi-omics and clinical data | Dynamic Bayesian networks, recurrent neural networks | Modeling immune system development, vaccination responses, disease progression |

| Spatial Integration | Spatial transcriptomics + proteomics + histology | Graph neural networks, spatial statistics | Characterizing tumor microenvironment, lymphoid tissue organization |

| Knowledge-Driven Integration | Multi-scale data with prior biological knowledge | Knowledge graphs, pathway enrichment | Placing novel findings in context of established immunology knowledge |

Machine learning approaches are particularly well-suited for integrating these diverse data types. Foundation models pretrained on large single-cell datasets can be fine-tuned for specific immunological questions, while transfer learning enables models trained on one data type to inform analyses of another [24] [1]. Risk-based approaches to data quality management, as highlighted in recent clinical data trends, help focus computational resources on the most critical data points for immunological discovery [27].

The future of computational immunology will be shaped by continued advances in all these data domains, with emerging technologies making each data type more comprehensive, quantitative, and accessible. The researchers and drug developers who can most effectively navigate and integrate this complex data landscape will lead the next wave of discoveries in immune-mediated diseases and therapies.

The field of immunology is increasingly relying on computational methods to decipher the complex mechanisms of the immune system. Machine learning (ML), a branch of artificial intelligence (AI), provides a robust framework for analyzing high-dimensional biological data. ML systems learn from data to make predictions without explicit programming, enhancing their performance through exposure to more data [28]. In immunological research, three primary ML categories have become foundational: supervised learning, which uses labeled datasets to train algorithms for prediction; unsupervised learning, which identifies hidden patterns in unlabeled data; and deep learning (DL), a subset of ML that uses multi-layered neural networks to model complex non-linear relationships [29] [30]. The integration of these approaches is transforming how researchers tackle challenges in vaccine development, cancer immunotherapy, and fundamental immune mechanism discovery.

Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Approaches

The selection of an appropriate machine learning approach depends on the research question, data type, and desired outcome. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, applications, and performance metrics of the three fundamental categories in immunology.

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Machine Learning Categories in Immunology

| Feature | Supervised Learning | Unsupervised Learning | Deep Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Learns a mapping function from labeled input-output pairs [28]. | Identifies inherent structures and patterns in unlabeled data [28]. | Uses neural networks with multiple layers to learn hierarchical data representations [31] [29]. |

| Primary Tasks | Classification (e.g., responder vs. non-responder), Regression (e.g., predicting binding affinity) [29]. | Clustering, Dimensionality reduction, Anomaly detection [28]. | Complex pattern recognition from raw data (e.g., images, sequences), Feature extraction [32] [31]. |

| Immunology Applications | Predicting vaccine efficacy, Neoantigen recognition, Classifying patient response to immunotherapy [29] [33]. | Discovering novel immune cell subtypes, Deconvoluting heterogeneous tissue samples, Identifying patient stratifications [31] [33]. | Analyzing whole-slide images for prognostic features, Predicting protein structures, Integrating multi-omics data [32] [31]. |

| Data Requirements | Large, high-quality labeled datasets [28]. | Unlabeled datasets; performance improves with data volume and quality. | Very large datasets; can learn directly from raw, high-dimensional data [31]. |

| Representative Algorithms | Random Forest, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Logistic Regression [28] [33]. | k-means, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), UMAP [31] [28]. | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Graph Neural Networks [32] [31]. |

| Interpretability | Generally moderate; model-specific interpretation tools available (e.g., feature importance) [33]. | Often high, as patterns like clusters can be biologically validated. | Traditionally low ("black box"); requires explainable AI (XAI) methods like Grad-CAM [32] [33]. |

| Example Performance | Multitask SVM identified malaria vaccine correlates (ESPY analysis) [33]. | k-means clustering revealed altered infant vaccine responses after congenital infection [33]. | CNN model for OSCC survival assessment achieved c-index = 0.809 [32]. |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Supervised Learning: Predicting Malaria Vaccine Protection

A study on the PfSPZ-CVac malaria vaccine utilized supervised learning to identify antibody correlates of protection from massive immune profiling data [33].

- Objective: To determine which antibody responses to the Plasmodium falciparum proteome were associated with protection from infection.

- Methods: Researchers trained and compared three models: Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and a Multitask Support Vector Machine (SVM). The Multitask SVM was designed to incorporate both time and dose response data, enhancing its ability to handle complex, high-dimensional proteomic data.

- Performance & Outcome: The Multitask SVM outperformed other models. Using a custom interpretation method called ESPY, the model identified specific antigens (CSP and PfEMP1) whose antibody patterns were strongly correlated with protection. The model maintained performance even after removing overlapping features, demonstrating its robustness in pinpointing biologically meaningful markers [33].

Unsupervised Learning: Uncovering Infant Immune Response Patterns

Research at Pwani University employed unsupervised learning to investigate how congenital infections alter infant immune responses to vaccination [33].

- Objective: To group infants based on their antibody response profiles without pre-defined labels, revealing the impact of early-life infections.

- Methods: The researchers applied k-means clustering to longitudinal antibody data from infants exposed to pathogens like CMV and HSV. This approach identified distinct clusters of infants with different immune trajectories.

- Performance & Outcome: The analysis revealed that early-life infection exposure was associated with significantly different vaccine-induced immune response patterns. These insights, which would be difficult to detect with traditional statistical methods, suggest that congenital infections can rewire the developing immune system, with implications for pediatric vaccine strategies [33].

Deep Learning: Prognostic Assessment in Oral Cancer

A study developed a deep learning platform to predict overall survival (OS) for patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) from whole-slide images [32].

- Objective: To assess OS in OSCC patients directly from histopathological images and compare training paradigms.

- Methods: The study evaluated four convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures under two paradigms: 1) Supervised DL (SDL) with precise annotations (the PathS model), and 2) Weakly Supervised DL (WSDL) using only slide-level labels. Explainable AI (XAI) via Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) was used to interpret model focus.

- Performance & Outcome: The supervised PathS model significantly outperformed both the WSDL approach and a conventional clinical signature (CS) model. Grad-CAM visualizations confirmed that the model focused on biologically relevant features, simultaneously identifying tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating immune cells as key prognostic predictors [32].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Deep Learning Models in OSCC Survival Prediction

| Model Type | Specific Model | Performance (c-index) | Key Features Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised DL | PathS Model | 0.809 | Tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating immune cells [32]. |

| Weakly Supervised DL | Not Specified | 0.707 | - |

| Clinical Signature | CS Model | 0.721 | Conventional clinical/pathological parameters [32]. |

| Multimodal Integration | PathS + CS Nomogram | 0.817 | Combined pathomics and clinical signatures [32]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The application of machine learning in immunology relies on a suite of computational "reagents" and platforms. The table below details key resources essential for conducting research in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Immunology

| Tool / Platform / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Immunology Research |

|---|---|---|

| Seurat [31] | Computational Framework (R) | A comprehensive toolkit for the analysis and interpretation of single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) data, including immune cell profiling. |

| Scanpy [31] | Computational Framework (Python) | A scalable toolkit for analyzing single-cell gene expression data, used for clustering, trajectory inference, and visualization of immune cells. |

| scVI [31] | Deep Learning Model (VAE) | A variational autoencoder for probabilistic representation and integration of single-cell omics data, accounting for batch effects and technical noise. |

| PIONEER AI Platform [29] | AI Platform | Accelerates personalized cancer vaccine development by rapidly screening and predicting immunogenic tumor neoantigens for vaccine inclusion. |

| Grad-CAM [32] | Explainable AI (XAI) Method | Provides visual explanations for decisions from deep learning models (e.g., CNNs), highlighting critical image regions like tumor and immune cells in histopathology. |

| AlphaFold [31] | Deep Learning Model | Predicts 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences with high accuracy, revolutionizing understanding of antibody-antigen interactions and immune protein functions. |

| UMAP [31] | Dimensionality Reduction | Visualizes high-dimensional single-cell data in 2D/3D, preserving cellular relationships and allowing researchers to visualize immune cell populations and states. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Visualizations

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate a generalized experimental workflow for an immunology ML project and the logical structure of a deep neural network.

ML Research Workflow in Immunology

Deep Neural Network Architecture

Comparative Framework of ML Algorithms and Their Immunology Applications

The design of therapeutic antibodies has been transformed by computational methods, shifting from traditional experimental approaches to sophisticated in silico tools. Rosetta, ProteinMPNN, and RFdiffusion represent three generations of protein design technology, each with distinct capabilities and applications in antibody engineering. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these platforms, focusing on their underlying methodologies, performance metrics, and experimental validation to inform researchers in selecting appropriate tools for specific antibody design challenges.

Methodologies & Design Philosophies

RosettaAntibodyDesign (RAbD): A Knowledge-Based Framework

RosettaAntibodyDesign (RAbD) employs a structural bioinformatics approach grounded in empirical data. It samples antibody sequences and structures by grafting complementary-determining regions (CDRs) from a curated set of canonical clusters [34]. The framework utilizes flexible-backbone design protocols with cluster-based constraints and performs sequence design according to amino acid sequence profiles of each cluster [34]. RAbD operates through highly customizable protocols that can optimize either total Rosetta energy or specific interface energy, allowing for redesign of single or multiple CDRs with loops of different lengths, conformations, and sequences [34].

ProteinMPNN: Inverse Folding for Sequence Design

ProteinMPNN adopts a machine learning approach to solve the inverse folding problem – predicting sequences that fold into a given protein backbone structure [35]. It utilizes a message-passing neural network (MPNN) architecture that iteratively processes information about residues in the local neighborhood of each position [35]. This structure-based embedding is then decoded to generate protein sequences likely to fold into the input structure. Unlike structure-generating models, ProteinMPNN requires a predefined backbone structure as input and focuses exclusively on optimizing the sequence [35].

RFdiffusion: De Novo Generation with Diffusion Models

RFdiffusion represents a paradigm shift through its denoising diffusion probabilistic model that generates novel protein structures de novo [36] [37]. The model is trained to recover solved protein structures corrupted with noise, enabling it to transform random noise into novel proteins during inference [35]. For antibody design, RFdiffusion has been fine-tuned on antibody complex structures and can generate full antibody variable regions targeting user-specified epitopes with atomic-level precision [36] [37]. Key innovations include global-frame-invariant framework conditioning and epitope targeting via hotspot features, enabling design of novel CDR loops while maintaining structural integrity [37].

Table 1: Core Methodological Comparison

| Feature | RosettaAntibodyDesign | ProteinMPNN | RFdiffusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Grafting & designing CDRs from clusters | Inverse folding (sequence design) | De novo structure generation |

| Design Approach | Knowledge-based sampling | Machine learning (MPNN) | Denoising diffusion model |

| Antibody Specificity | Specifically trained for antibodies | General protein model | Fine-tuned on antibody complexes |

| Key Innovation | Cluster-based CDR grafting | Message-passing neural networks | Conditional diffusion with framework invariance |

| Reference | [34] | [35] | [36] [37] |

Performance Metrics & Experimental Validation

RosettaAntibodyDesign Performance

RAbD has been rigorously benchmarked on diverse antibody-antigen complexes, demonstrating robust performance metrics. In simulations performed with antigen present, RAbD achieved 72% recovery of native amino acid types for residues contacting the antigen, compared to only 48% in simulations without antigen [34]. The framework introduced novel evaluation metrics including the Design Risk Ratio (DRR), which measures recovery of native CDR lengths and clusters relative to their sampling frequency [34]. RAbD achieved DRRs between 2.4 and 4.0 for non-H3 CDRs, indicating strong preferential selection of native features [34]. Experimental validation demonstrated 10 to 50-fold affinity improvements when replacing individual CDRs with designed lengths and clusters [34]. In SARS-CoV-2 applications, RAbD successfully engineered antibodies binding multiple variants of concern after specificity switching from SARS-CoV-1 templates [38].

ProteinMPNN Performance

In benchmark evaluations, ProteinMPNN achieves approximately 53% sequence recovery rate (percentage of generated residues matching native amino acids at corresponding positions), significantly outperforming Rosetta's 33% recovery for the same proteins [35]. ProteinMPNN demonstrates particular strength in rescuing failed designs, increasing stability, enhancing solubility, and redesigning membrane proteins for soluble expression [35]. While not antibody-specific in its base form, its robust inverse folding capability makes it valuable for antibody sequence optimization when paired with appropriate structural inputs.

RFdiffusion Performance

The antibody-specialized RFdiffusion has achieved groundbreaking success in de novo antibody design, with cryo-EM validation confirming binding poses and atomic-level accuracy of designed CDR conformations [36] [39]. Experimental characterization demonstrated initial computational designs with modest affinity (nanomolar Kd) that could be matured to single-digit nanomolar binders while maintaining intended epitope specificity [36] [37]. High-resolution structures of designed antibodies validated accurate conformations of all six CDR loops in single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) [36]. The method has successfully generated binders against multiple therapeutically relevant targets including influenza hemagglutinin, Clostridium difficile toxin B, RSV, SARS-CoV-2 RBD, and IL-7Rα [36] [37].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics

| Metric | RosettaAntibodyDesign | ProteinMPNN | RFdiffusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native AA Recovery | 72% (interface residues) [34] | ~53% (general proteins) [35] | Atomic-level accuracy (cryo-EM validated) [36] |

| Affinity Improvement | 10-50 fold experimentally [34] | N/A (sequence design only) | Nanomolar binders, improvable to single-digit nM [36] |

| Structural Accuracy | DRR: 2.4-4.0 for CDRs [34] | N/A (requires input structure) | All CDR loops accurate (experimentally confirmed) [36] |

| Design Scope | CDR grafting & optimization | Sequence design for given structure | Full de novo antibody generation |

| Experimental Success | Yes (multiple applications) [34] [38] | Yes (general protein design) [35] | Yes (de novo antibodies) [36] [39] |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

RosettaAntibodyDesign Benchmarking Protocol

The rigorous benchmarking of RAbD involved a set of 60 diverse antibody-antigen complexes [34]. The protocol implemented two distinct design strategies: optimizing total Rosetta energy and optimizing interface energy alone [34]. Simulations were performed both in the presence and absence of antigen to quantify antigen-dependent effects. The evaluation introduced novel metrics including the Design Risk Ratio (frequency of native feature recovery divided by sampling frequency) and Antigen Risk Ratio (native feature frequency with antigen present divided by frequency without antigen) [34]. This systematic approach enabled quantitative assessment of design accuracy and antigen influence.

RFdiffusion Antibody Design Pipeline

The de novo antibody design workflow begins with fine-tuned RFdiffusion generating antibody structures conditioned on a specified framework and epitope [36] [37]. The process includes:

- Framework conditioning using the template track to provide pairwise distances and dihedral angles

- Epitope targeting via one-hot encoded hotspot residues

- CDR generation through iterative denoising while sampling rigid-body placement

- Sequence design using ProteinMPNN on generated backbones

- Filtering with fine-tuned RoseTTAFold2 for structural self-consistency [36] [37]

This pipeline has been validated for both single-domain antibodies (VHHs) and scFvs, with experimental characterization involving yeast surface display screening, SPR binding assays, and high-resolution structural validation by cryo-EM [36].

ProteinMPNN for Immunogenicity Reduction

Recent advancements have adapted ProteinMPNN with novel decoding strategies to enhance therapeutic suitability. The CAPE-Beam decoding strategy minimizes cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) immunogenicity risk by constraining designs to consist only of k-mers predicted to avoid CTL presentation or subject to central tolerance [40]. This approach maintains structural similarity to target proteins while incorporating more human-like k-mers, significantly reducing potential immunogenicity risks in therapeutic applications [40].

Workflow comparison of the three antibody design platforms.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PyIgClassify Database | Provides canonical CDR clusters for grafting [34] | Essential for RosettaAntibodyDesign knowledge-based approach |

| Yeast Surface Display | High-throughput screening of designed antibodies [36] | Validation for RFdiffusion designs (testing ~9,000 designs/target) |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Quantitative binding affinity measurement [36] | Affinity validation (Kd determination) for designed binders |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy | High-resolution structural validation [36] [39] | Atomic-level accuracy confirmation of CDR conformations |

| OrthoRep | In vivo continuous evolution system [36] | Affinity maturation of initial computational designs |

| AlphaFold2/3 | Structure prediction for validation [35] | Self-consistency filtering and design validation |

| Fine-tuned RoseTTAFold2 | Antibody-specific structure prediction [36] [37] | Filtering RFdiffusion designs by self-consistency |

The comparative analysis of RosettaAntibodyDesign, ProteinMPNN, and RFdiffusion reveals a rapid evolution in computational antibody design capabilities. RosettaAntibodyDesign provides a robust, knowledge-based framework for antibody optimization with proven experimental success in affinity maturation and specificity switching. ProteinMPNN offers powerful sequence design capabilities that can complement structural generation methods, with recent extensions addressing critical therapeutic concerns like immunogenicity reduction. RFdiffusion represents a transformative advance through de novo generation of antibodies targeting specified epitopes with atomic-level precision, as validated by high-resolution structural methods. The choice among these tools depends on the design objective: RAbD for knowledge-based optimization, ProteinMPNN for sequence design on existing structures, and RFdiffusion for truly de novo antibody generation. Integrating these complementary approaches provides the most powerful framework for addressing the complex challenges of therapeutic antibody development.

The field of vaccine development is undergoing a rapid transformation, moving from traditional empirical approaches to rational, computation-driven strategies. Central to this shift is immunoinformatics, an interdisciplinary field that combines principles of bioinformatics and immunology to support the design and development of vaccines and therapeutic agents [41]. At the heart of immunoinformatics lies epitope prediction – the computational identification of specific regions on antigens that are recognized by the immune system. These epitopes are crucial for eliciting targeted immune responses, and accurate prediction significantly accelerates vaccine research while reducing the need for extensive experimental screening [42] [43].

The foundation of immunoinformatics was established with the creation of the International ImMunoGeneTics information system (IMGT) in 1989, which provided a standardized framework for analyzing immunoglobulin and T cell receptor genes [41]. This database, along with other resources like the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB), has enabled the development of sophisticated computational tools that can predict epitopes with increasing accuracy [44]. The application of these approaches was particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, where computational techniques based on immunoinformatics significantly accelerated the development of vaccines and diagnostic tests [43] [41].

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have further revolutionized epitope prediction, delivering unprecedented accuracy, speed, and efficiency [42]. Deep learning models have demonstrated the capability to identify genuine epitopes that were previously overlooked by traditional methods, providing a crucial advancement toward more effective antigen selection [42]. This comparative analysis examines the current landscape of epitope prediction tools and immunoinformatics pipelines, providing researchers with actionable insights for selecting and implementing these computational approaches in vaccine development workflows.

Comparative Analysis of Epitope Prediction Tools and Methods

Traditional vs. AI-Driven Epitope Prediction Methods

Traditional epitope identification relied on experimental methods like X-ray crystallography, peptide microarrays, and mass spectrometry, which are accurate but slow, costly, and low-throughput [42] [43]. Early computational approaches used motif-based methods, homology-based prediction, and physicochemical scales, but these often failed to detect novel epitopes and achieved limited accuracy (approximately 50-60%) [42]. For B-cell epitopes specifically, traditional computational methods struggled because many epitopes are conformational rather than linear [42].

In contrast, modern AI-driven approaches, particularly deep learning, have revolutionized epitope prediction by learning complex sequence and structural patterns from large immunological datasets [42]. Unlike motif-based rules, deep neural networks can automatically discover nonlinear correlations between amino acid features and immunogenicity [42]. The performance difference is substantial: recent AI models have demonstrated accuracy improvements of up to 59% in Matthews correlation coefficient for B-cell epitope prediction and 26% higher performance for T-cell epitope prediction compared to traditional methods [42].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Epitope Prediction Methods

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Reported Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Computational | BepiPred, LBtope, NetMHC (early versions) | Simple implementation, interpretable rules | Low accuracy (~50-60%), misses novel epitopes | ROC AUC: ~0.60-0.70 [42] |

| Modern ML/Deep Learning | MUNIS, GraphBepi, NetBCE, DeepImmuno | High accuracy, identifies novel epitopes, handles complex patterns | Requires large datasets, complex implementation | B-cell: 87.8% accuracy (AUC=0.945) [42] |

| Convolutional Neural Networks | DeepImmuno-CNN, NetBCE | Excellent for spatial pattern recognition, interpretable outputs | Requires careful architecture design | ROC AUC: ~0.85 [42] |

| Recurrent Neural Networks | MHCnuggets, DeepLBCEPred | Effective for sequence data, handles variable lengths | Computationally intensive for long sequences | 4x increase in predictive accuracy [42] |

| Graph Neural Networks | GraphBepi | Captures structural relationships, ideal for conformational epitopes | Requires structural data | Experimental validation success [42] |

Specialized AI Architectures for Epitope Prediction

Different deep learning architectures offer distinct advantages for epitope prediction tasks, each suited to particular aspects of the problem:

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been successfully applied to predict both T-cell and B-cell epitopes. For T-cell epitope prediction, models like DeepImmuno-CNN explicitly integrate HLA context, processing peptide-MHC pairs with convolutional layers and rich physicochemical features, markedly improving precision and recall across diverse benchmarks [42]. For B-cell epitopes, NetBCE combines CNN and bidirectional LSTM with attention mechanisms, achieving a cross-validation ROC AUC of approximately 0.85, substantially outperforming traditional tools [42].