Decoding B-Cell Evolution: A Guide to Phylogenetic Analysis for Therapeutic Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of phylogenetic analysis to B-cell receptor (BCR) repertoires.

Decoding B-Cell Evolution: A Guide to Phylogenetic Analysis for Therapeutic Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of phylogenetic analysis to B-cell receptor (BCR) repertoires. It covers the foundational principles that distinguish B-cell phylogeny from species evolution, explores current methodological approaches and computational tools for clonal family delimitation, and addresses key challenges and optimization strategies for robust analysis. Further, it validates and compares the performance of leading tools like SCOPer, Change-O, and mPTP, and highlights how these techniques are being applied in cutting-edge research to identify broadly neutralizing antibodies and guide the development of vaccines and therapeutics against evolving viral threats and cancer.

The Engine of Adaptation: How B-Cell Phylogeny Drives Immune Evolution

The reconstruction of evolutionary history through phylogenetics is a cornerstone of modern biology. While traditionally applied to the evolution of species over geological timescales, these principles are now pivotal for understanding rapid cellular evolution within the adaptive immune system. This whitepaper delineates the fundamental biological distinctions between B-cell phylogeny, which traces the somatic evolutionary history of B-cell clones within an individual, and species phylogeny, which reconstructs the genetic heritage across species or populations over millennia. Framing these differences is essential for researchers and drug development professionals applying phylogenetic analysis to B-cell repertoire evolution, as the core assumptions, mechanisms, and analytical methods differ significantly between these domains [1] [2].

Core Biological Distinctions

The evolutionary processes governing B cells and species operate on different scales, under different mechanisms, and with distinct ends. The table below summarizes the core biological distinctions that inform methodological choices in phylogenetic analysis.

Table 1: Key Biological Distinctions Between B-Cell and Species Phylogeny

| Feature | B-Cell Phylogeny | Species Phylogeny |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Scale | Within an individual organism (somatic) | Between populations or species (germline) |

| Primary Mechanism | Somatic Hypermutation (SHM) and antigen-driven selection [1] | Natural selection and genetic drift on random mutations |

| Time Scale | Days to weeks (e.g., during an immune response) [3] | Thousands to millions of years (macroevolution) |

| Tree Root | Known or inferred unmutated germline sequence [4] | Unknown; usually inferred using outgroups or molecular clocks |

| Selection Pressure | Strong selection for antigen binding affinity [4] | Diverse and variable selection pressures |

| Key Processes | V(D)J recombination, SHM, affinity maturation, class switching [1] | Mutation, recombination, gene flow, speciation |

| Independence Assumption | Sites do not evolve independently (SHM hotspots/coldspots) [1] | Sites often assumed to evolve independently in standard models |

| Tree Topology | Often asymmetric, with multifurcations [2] | Typically bifurcating in most models |

Methodological Implications for Phylogenetic Analysis

The biological distinctions in Table 1 directly translate into divergent methodological practices for reconstructing and interpreting phylogenetic trees.

Data Processing and Tree Building

- Sequence Alignment and Clonal Clustering: B-cell receptor (BCR) sequences must first be aligned to species-specific germline V, D, and J gene references (e.g., using IMGT/V-QUEST or IgBLAST) rather than undergoing multiple sequence alignment [1]. Critically, tree building is only performed on sequences from the same clone, defined by a shared V(D)J rearrangement event. Clonal clustering with tools like SCOPer or Partis is therefore a essential, prerequisite step [1] [2].

- Tree Building Methods: While standard phylogenetic methods (parsimony, likelihood, distance) are used, B-cell phylogenetics often employs specialized tools that account for unique biological features.

- Selection Analysis: A primary application of B-cell trees is to detect antigen-driven selection. Methods like BASELINe use tree topology and branch lengths to identify positive selection in the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) versus negative selection in the framework regions (FWRs) [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Phylogenetic Software in B-Cell and Species Evolution

| Software | Method | Key Features / Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| IgPhyML [1] | Maximum Likelihood | Incorporates a codon substitution model with SHM hotspots/coldspots; for B-cell lineages. |

| ClonalTree [4] | Minimum Spanning Tree (MST) & Abundance | Integrates cellular genotype abundance for fast B-cell lineage tree inference. |

| GCtree [1] | Maximum Parsimony | Uses a branching process model and genotype abundances; accurate but computationally intensive. |

| RAxML [1] | Maximum Likelihood | General-purpose species tree inference; high efficiency on large datasets. |

| BEAST [1] | Bayesian | Infers species divergence times and evolutionary rates; uses molecular clock models. |

Experimental Workflows in B-Cell Phylogenetics

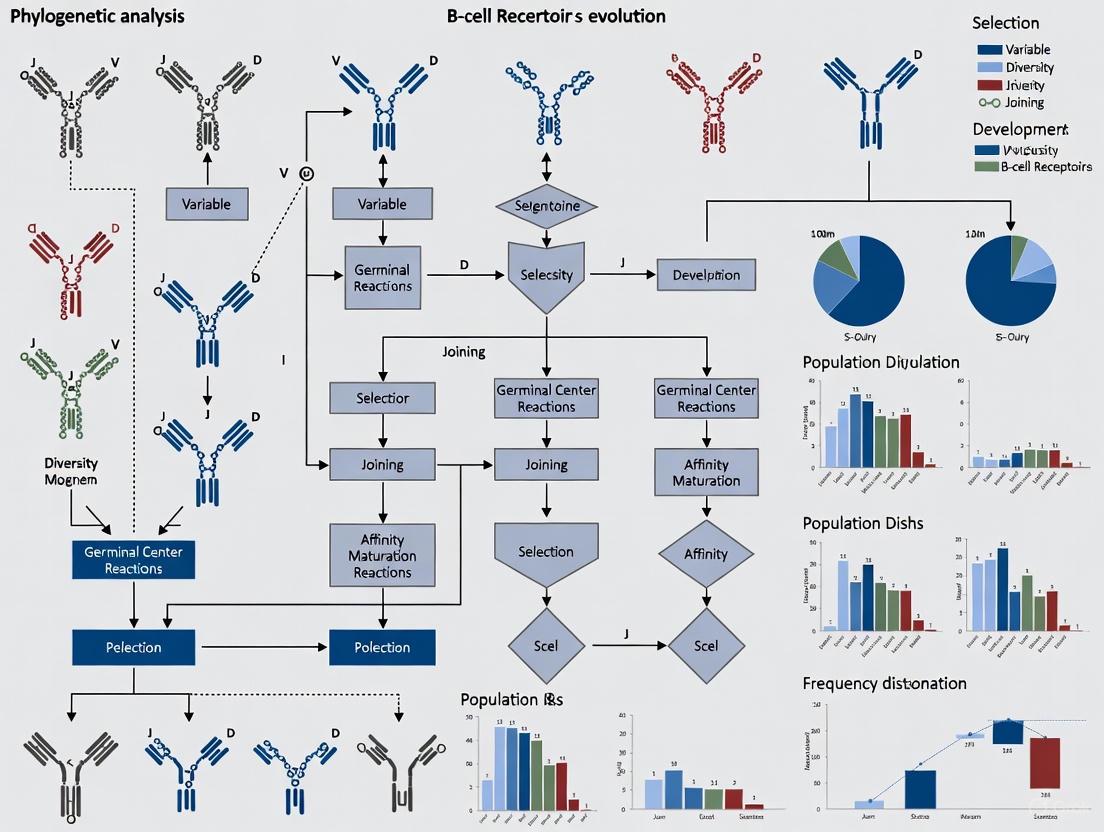

A typical workflow for B-cell phylogenetic analysis integrates single-cell sequencing with sophisticated computational pipelines. The diagram below outlines the key steps from sample preparation to tree-based analysis.

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protocol A: Building a B-Cell Lineage Tree from Single-Cell RNA-Seq Data

This protocol is adapted from current best practices for processing paired single-cell RNA and BCR sequencing data [1].

- BCR Sequence Processing and Error Correction: Raw BCR sequencing reads from platforms like 10X Genomics are processed using tools such as Cell Ranger [5] or pRESTO [1] to correct sequencing errors, which are critical as they can be misinterpreted as mutations.

- Germline Alignment and Clonal Clustering: The corrected sequences are aligned to germline V, D, and J gene databases (e.g., IMGT) using IgBLAST or MiXCR. Sequences are then grouped into clones based on shared V(D)J rearrangement and similar CDR3 regions using tools like SCOPer or Partis [1].

- Tree Inference with Specialized Software: For a given clone, a multiple sequence alignment is created. Phylogenetic trees are inferred using B-cell-specific tools like IgPhyML (for maximum likelihood with SHM models) or ClonalTree (for fast MST-based inference with abundance data) [1] [4].

- Ancestral State Reconstruction: The unmutated germline sequence is used to root the tree. Intermediate node sequences (ancestral BCRs) are reconstructed using parsimony or likelihood methods available in packages like Alakazam or Dowser [1] [2].

Protocol B: Investigating the Functional Impact of Mechanical Forces

Recent research highlights that B cells use active physical forces to extract antigen, a process that directly influences clonal fitness and evolution [3]. The following diagram models this tug-of-war mechanism.

The theoretical framework models the system with a combined free energy landscape: U(xa, xb; t) = Ua(xa) + Ub(xb) + Vpull(xa + xb; t), where Vpull(x; t) = -F(t)x represents the deformation caused by the pulling force F(t). The stochastic dynamics of bond rupture and thus antigen acquisition are governed by Langevin equations, mapping binding characteristics to clonal fitness [3]. This mechanical proofreading enhances affinity discrimination, and the predicted optimal force range of 10-20 pN aligns with experimental measurements [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Cutting-edge research in B-cell phylogenetics and evolution relies on a specific set of reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for B-Cell Phylogenetics

| Research Reagent | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell 5' Kit (10x Genomics) | Paired V(D)J and gene expression profiling from single cells. | Enables linking BCR sequence to cell phenotype [1]. |

| Germline Gene Database | Reference for V(D)J alignment and germline inference. | IMGT/GENE-DB; essential for root identification [1]. |

| hCD40L-expressing L-cells + IL-21 | In vitro B-cell immortalization and culture. | Critical for generating immortalized B-cell libraries for functional screening [6]. |

| Anti-Trout IgM mAb (1.14) | Depletion of IgM in serum neutralization assays. | Used in fish models (e.g., trout) to confirm IgM-mediated protection [7]. |

| DNA-based Tension Probes | Measurement of molecular forces exerted by live B cells. | Validates theoretical models of force usage (e.g., 10-20 pN range) [3]. |

| 6-Chloro-1-tetralone | 6-Chloro-1-tetralone, CAS:26673-31-4, MF:C10H9ClO, MW:180.63 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Abecomotide | Abecomotide, CAS:907596-50-3, MF:C45H79N13O16, MW:1058.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

B-cell phylogeny and species evolution represent two distinct paradigms of descent with modification. B-cell phylogeny is characterized by its somatic scale, rapid pace, directed and strong selection pressures, and dependence on specific molecular mechanisms like SHM. These distinctions necessitate specialized analytical methods and experimental frameworks. A deep understanding of these differences is not merely academic; it is fundamental for accurately reconstructing antibody lineages, identifying broadly neutralizing antibodies, and designing next-generation vaccines and therapeutics that harness the body's own evolutionary machinery. As single-cell technologies and biophysical models continue to advance, they will further refine our ability to trace and interpret the evolutionary history of the immune system.

The adaptive immune system's ability to recognize and neutralize an almost limitless array of pathogens hinges on two sophisticated genetic diversification mechanisms: V(D)J recombination and somatic hypermutation (SHM). V(D)J recombination assembles the primary B-cell receptor (BCR) repertoire in developing B cells in the bone marrow, while SHM fine-tunes antibody affinity for antigen within germinal centers of secondary lymphoid tissues following antigen exposure [8] [9]. Together, these processes generate the extraordinary diversity of antibodies essential for effective humoral immunity. Within the context of modern phylogenetic analysis of B-cell repertoires, understanding these mechanisms is paramount for tracing clonal lineages, reconstructing evolutionary histories of antibody responses, and designing novel vaccine strategies [2] [1]. This technical guide examines the molecular mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and analytical frameworks that underpin these fundamental immunological processes.

Molecular Mechanisms of V(D)J Recombination

V(D)J recombination is the site-specific genetic rearrangement process that occurs during early B cell development, generating the initial diversity of immunoglobulins.

Genetic Architecture and the 12/23 Rule

The variable regions of immunoglobulin heavy and light chains are encoded by multiple gene segments located on different chromosomes. The heavy chain variable region is assembled from Variable (V), Diversity (D), and Joining (J) segments, while the light chain (kappa or lambda) uses only V and J segments [8] [10]. The recombination process is guided by Recombination Signal Sequences (RSSs) that flank each coding segment. Each RSS consists of a heptamer (consensus 5'-CACAGTG-3'), a nonamer (consensus 5'-ACAAAAACC-3'), and a spacer region of either 12 or 23 base pairs [8]. The "12/23 rule" dictates that recombination occurs only between segments flanked by RSSs with different spacer lengths, ensuring proper segment joining [10].

Table 1: Human Immunoglobulin Gene Segments and Genomic Organization

| Locus | Chromosome | Gene Segments | Constant Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| IGH | 14 | 44 V, 27 D, 6 J | Cμ, Cδ, Cγ, Cε, Cα |

| IGK | 2 | Numerous V, 5 J | Cκ |

| IGL | 22 | Numerous V, 4-5 J | Cλ |

Enzymatic Machinery and Breaking/Repair Mechanisms

V(D)J recombination is initiated by the lymphoid-specific proteins RAG1 and RAG2 (Recombination-Activating Genes), which together form the V(D)J recombinase [8] [10]. The mechanism involves a series of coordinated steps:

- Synapsis and Nicking: The RAG complex binds one RSS and introduces a single-strand nick between the coding segment and the heptamer of the RSS, creating a free 3'-OH group [10].

- Hairpin Formation and Cleavage: The 3'-OH group attacks the complementary DNA strand, forming a double-strand break with a hairpin-sealed coding end and a blunt signal end [10].

- Coding End Processing: The hairpin coding ends are opened by the Artemis nuclease, often asymmetrically to generate P-nucleotides [10].

- Junctional Diversity: The enzyme Terminal deoxynucleotidyl Transferase (TdT) adds N-nucleotides randomly to the coding ends before ligation [10].

- Ligation: The processed coding ends are ligated by Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway proteins, including DNA-PKcs, XRCC4, XLF, and DNA Ligase IV [8] [10].

The combination of P-nucleotide addition, N-region nucleotide insertion by TdT, and imprecise joining at junctions creates tremendous junctional diversity, substantially expanding the antibody repertoire beyond what would be achieved by combinatorial diversity alone [10].

Diagram 1: V(D)J recombination mechanism showing coding and signal joint formation.

Somatic Hypermutation and Affinity Maturation

Following antigen exposure, activated B cells migrate to germinal centers where SHM introduces point mutations into the variable regions of immunoglobulin genes, enabling affinity maturation.

The SHM Molecular Mechanism

SHM is initiated by Activation-Induced Cytidine Deaminase (AID), which deaminates cytosine residues to uracils in single-stranded DNA substrates within the variable region exons [11]. This process is tightly coupled to transcription, as AID requires single-stranded DNA for activity. The resulting U:G mismatches are then processed by multiple DNA repair pathways:

- Base Excision Repair (BER): Uracils are recognized by uracil-DNA glycosylase (UNG), creating abasic sites that are processed by apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases, leading to transition or transversion mutations at the original C:G base pairs [8].

- Mismatch Repair (MMR): The U:G mismatch is recognized by the MMR machinery, which involves proteins such as MSH2/MSH6, leading to error-prone repair by polymerases like Pol η that introduces mutations primarily at adjacent A:T base pairs [8].

AID preferentially targets cytosine residues within specific hotspot motifs (WRCH, where W = A/T, R = A/G, H = A/C/T), with mutation frequency influenced by the surrounding sequence context [11].

Beyond Affinity Improvement: Generation of de novo Specificities

Recent research has revealed that SHM's role extends beyond merely improving pre-existing antigen affinity. Under conditions of limited B cell competition, SHM can generate de novo antigen recognition to multiple epitopes across diverse antigens [12]. Phylogenetic analyses have identified diverse mutational pathways leading to these new antigen affinities, demonstrating that SHM can reshape antibody specificity rather than simply "ripening" existing interactions [12]. This flexibility highlights the adaptive immune system's capacity to explore antibody-antigen interactions beyond those encoded by the primary V(D)J repertoire.

Table 2: Key Enzymes in Somatic Hypermutation and Their Functions

| Enzyme/Pathway | Function in SHM | Mutation Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| AID | Cytosine deamination in ssDNA | Initiates all SHM at C:G base pairs |

| UNG | Uracil excision from DNA | Base excision repair leading to transitions/transversions at C:G |

| MSH2/MSH6 | Mismatch recognition | Recruits error-prone polymerases for mutations at A:T pairs |

| Pol η | Error-prone DNA synthesis | Introduces mutations primarily at A:T base pairs |

| BER Pathway | Processes abasic sites | Generates mutations at original C:G sites |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Diversity Mechanisms

Analyzing V(D)J Recombination Products

Protocol 1: Bulk BCR Sequencing and Analysis

- Sample Preparation: Isolate genomic DNA or RNA from B cells (e.g., from peripheral blood mononuclear cells or lymphoid tissues).

- Library Preparation: Amplify immunoglobulin variable regions using multiplex PCR primers targeting V and J gene families or 5' RACE-based methods.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence amplified products using platforms such as Illumina to obtain millions of BCR sequences.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control and Error Correction: Use tools like pRESTO to remove low-quality sequences and correct sequencing errors [2].

- V(D)J Assignment: Align sequences to germline V, D, and J gene references using IgBLAST or IMGT/V-QUEST to identify gene usage and junctional regions [2].

- Clonal Grouping: Cluster sequences into clones based on shared V and J genes and similar CDR3 lengths using tools like SCOPer or Partis [1].

- Junctional Analysis: Extract CDR3 sequences and analyze N/P nucleotide additions and indel patterns.

Protocol 2: Single-Cell BCR Sequencing

- Single-Cell Isolation: Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or microfluidic platforms (e.g., 10X Genomics) to isolate individual B cells.

- Library Preparation: Employ commercially available systems (e.g., 10X Genomics 5' Immune Profiling) that capture paired heavy and light chain information.

- Sequence Processing: Use Cell Ranger for demultiplexing, barcode processing, and V(D)J contig assembly [1].

- Downstream Analysis: Analyze paired heavy-light chain relationships and clonal families with tools like Platypus or Alakazam [1].

Tracking Somatic Hypermutation in Antigen-Specific Responses

Protocol 3: SHM Analysis in Vaccine Responses

- Sample Collection: Collect peripheral blood B cells before and after vaccination at multiple time points (e.g., weeks 0, 2, 4, 8).

- Antigen-Specific B Cell Sorting: Use fluorescently labeled antigen baits (e.g., HIV Env proteins for HIV vaccine studies) to sort antigen-reactive B cells by FACS [13].

- Single-Cell BCR Sequencing: Sequence BCRs from sorted cells using single-cell methods as described in Protocol 2.

- SHM Analysis:

- Mutation Identification: Compare each BCR sequence to its inferred germline precursor to identify somatic mutations.

- Lineage Tree Construction: Build phylogenetic trees for each B cell clone using tools such as IgPhyML or Dowser to visualize mutational pathways [1].

- Selection Analysis: Apply selection tests (e.g., BASELINe) to identify evidence of antigen-driven selection in complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) versus framework regions (FWRs) [2].

Diagram 2: BCR repertoire analysis workflow from sample to phylogenetic insights.

Research Reagent Solutions for B Cell Repertoire Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for B Cell Receptor Analysis

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Application and Function |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Platforms | 10X Genomics Immune Profiling, BD Rhapsody | Simultaneous capture of paired heavy and light chain BCR sequences from individual B cells |

| Sequence Alignment Tools | IgBLAST, IMGT/V-QUEST, MiXCR | Annotation of V(D)J gene segments and identification of somatic mutations |

| Clonal Grouping Software | SCOPer, Partis, Change-O | Statistical inference of clonally related BCR sequences from the same ancestral cell |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Packages | IgPhyML, Dowser, GCTree | Building B cell lineage trees, inferring intermediate sequences, and testing selection pressures |

| Germline Reference Databases | IMGT GENE-DB, OGRDB | Species-specific references for germline V, D, and J gene sequences |

| Antigen Probes | HIV Env trimer baits, fluorescently labeled antigens | Isolation of antigen-specific B cells via FACS for functional repertoire analysis |

Applications in Vaccine Design and Immunotherapy

The principles of V(D)J recombination and SHM have direct applications in rational vaccine design and therapeutic antibody development. For complex pathogens like HIV, researchers are designing germline-targeting immunogens that specifically engage naive B cells bearing BCRs with potential to develop into broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) [13]. Sequential immunization strategies then use booster immunogens designed to guide these B cell lineages through appropriate mutational pathways via SHM to achieve broad neutralization capacity [13].

Clinical trials (e.g., IAVI G001 and HVTN 301) are testing engineered immunogens like eOD-GT8 and 426c.Mod.Core that target precursors of VRC01-class bNAbs, which recognize the CD4-binding site of HIV Env [13]. These approaches rely on deep understanding of SHM patterns and lineage tracing to design effective vaccination protocols. Similarly, phylogenetic analyses of B cell clones from individuals who naturally develop bNAbs against HIV provide blueprints for reverse engineering vaccination strategies that recapitulate these mutational trajectories [2].

V(D)J recombination and somatic hypermutation represent two genetically distinct but functionally complementary mechanisms that generate and refine antibody diversity throughout B cell development. While V(D)J recombination creates the primary repertoire through combinatorial assembly and junctional diversity, SHM introduces point mutations that enable affinity maturation and, as recent evidence shows, can even generate entirely new antigen specificities not present in the primary repertoire [12]. Advanced single-cell sequencing technologies coupled with sophisticated phylogenetic analysis tools are revolutionizing our ability to track these processes at unprecedented resolution, providing insights crucial for developing next-generation vaccines and immunotherapies. As these analytical methods continue to evolve, they will further illuminate the complex evolutionary dynamics of B cell responses across infection, vaccination, autoimmunity, and cancer.

The adaptive immune system employs a sophisticated evolutionary process to generate high-affinity antibodies against diverse pathogens. This whitepaper details the mechanisms of clonal expansion and affinity maturation, framing them within the context of B cell receptor (BCR) repertoire evolution and phylogenetic analysis. We examine how somatic hypermutation (SHM) and germinal center (GC) selection operate as a micro-evolutionary process, producing antibodies with progressively higher antigen affinity. For researchers and drug development professionals, this document provides a technical guide to the underlying biology, current analytical methodologies, and applications in therapeutic development, complete with structured data and experimental workflows.

The humoral immune response is fundamentally a process of clonal selection and evolution. Upon encountering an antigen, B cells that recognize it are activated and undergo rapid proliferation, a phase known as clonal expansion [14]. This creates a large population of B cells derived from a common progenitor, forming the substrate for subsequent adaptation. The process of affinity maturation refines this response, using iterative rounds of mutation and selection within germinal centers to produce B cells and antibodies with significantly increased affinity for the inciting antigen [14] [15].

In the broader context of phylogenetic B-cell repertoire analysis, each clonally expanded family of B cells represents a distinct lineage whose evolutionary history can be reconstructed from its BCR sequences. High-throughput sequencing and advanced computational tools now allow researchers to trace this micro-evolution in exquisite detail, providing insights critical for understanding immune responses, designing effective vaccines, and developing therapeutic antibodies [16] [1].

Core Biological Mechanisms

The Germinal Center Reaction

Affinity maturation is a structured process occurring within the germinal centers of secondary lymphoid organs, such as lymph nodes and the spleen [14] [17]. The germinal center is functionally divided into two zones:

- Dark Zone: Here, activated B cells (centroblasts) undergo massive clonal expansion. During multiple rounds of cell division, their immunoglobulin genes are targeted by somatic hypermutation (SHM), introducing point mutations at a rate approximately 1,000,000 times higher than the background mutation rate in other cell lines [14] [17].

- Light Zone: B cells (now called centrocytes) migrate here to be tested for antigen affinity. They must successfully bind antigen presented by follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) and receive survival signals from T follicular helper (TFH) cells [14]. B cells with mutations that confer higher affinity for the antigen are positively selected and may re-enter the dark zone for further rounds of mutation and selection. Low-affinity B cells undergo apoptosis [14] [17]. This iterative process can lead to antibodies with affinities several-fold greater than those produced in the initial primary immune response [14].

The following diagram illustrates the cyclical nature of this process.

Molecular Drivers: Somatic Hypermutation and Selection

Somatic Hypermutation (SHM) is the engine of diversity in affinity maturation. The enzyme activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) initiates SHM by deaminating cytosine to uracil in the variable regions of immunoglobulin genes [17]. Subsequent error-prone repair by DNA polymerases introduces point mutations, insertions, and deletions at a high frequency. This results in 1-2 mutations per complementarity-determining region (CDR) per cell generation [14]. The CDRs are the antigen-binding sites of the antibody, and mutations here directly alter binding specificity and affinity.

Clonal selection is the force that shapes this random variation. Because resources in the germinal center (antigen and T cell help) are limited, B cell progeny must compete for survival [14]. Only B cells whose mutated BCRs bind antigen with sufficient affinity receive pro-survival signals, a process often described as Darwinian evolution on a cellular level [18]. Over several rounds of this mutation-and-selection cycle, the average affinity of the B cell population for the antigen increases significantly.

Phylogenetic Analysis of B Cell Repertoires

Phylogenetic trees constructed from BCR sequencing data provide a powerful quantitative framework for studying clonal expansion and affinity maturation. These trees map the evolutionary history of a B cell clone, tracing the accumulation of SHMs from a common ancestor [1] [2].

Building B Cell Phylogenies

Constructing accurate B cell phylogenies involves a multi-step computational process [1]:

- Sequence Pre-processing & Error Correction: Raw BCR sequences are processed using tools like pRESTO (for bulk data) or Cell Ranger (for 10X Genomics single-cell data) to correct sequencing errors [1].

- Germline Alignment & Clonal Clustering: Sequences are aligned to germline V, D, and J gene references using specialized tools (e.g., IgBLAST, IMGT V-QUEST). Sequences originating from the same ancestral V(D)J recombination event are then grouped into clones using tools like SCOPer or Partis [1].

- Tree Building: Phylogenetic trees are inferred for each clone using the pattern of shared mutations. Common methods include:

- Maximum Likelihood (ML): Uses a model of nucleotide change to find the most likely tree topology and branch lengths. Tools: IgPhyML, RAxML [1] [19].

- Maximum Parsimony (MP): Finds the tree requiring the fewest number of mutations. Tools: Alakazam, GCTree [1].

- Bayesian Methods: Estimate a posterior distribution of likely trees. Tools: BEAST2, RevBayes [1].

Table 1: Common Phylogenetic Tree-Building Methods and Software for B Cell Repertoire Analysis

| Method | Underlying Principle | Example Software | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Likelihood | Finds the tree with the highest probability given the sequence data and an evolutionary model. | IgPhyML, RAxML, Phangorn | High accuracy; incorporates a model of sequence evolution; robust to homoplasy. | Computationally intensive for very large datasets. |

| Maximum Parsimony | Finds the tree requiring the smallest number of total mutations. | Alakazam, GCTree, Immunarch | Computationally fast; intuitive. | Can be biased when mutations are common (saturation). |

| Bayesian Inference | Estimates the posterior probability distribution of trees. | BEAST2, RevBayes, ImmuniTree | Provides measures of statistical confidence (posterior probabilities). | Very computationally intensive; complex setup. |

| Distance-Based | Clusters sequences based on pairwise genetic distances. | IgTree, neighbor-joining in PHYLIP | Extremely fast. | Lower accuracy; discards information in the sequence data. |

The following workflow outlines the key steps for obtaining a B cell phylogeny from raw sequencing data.

Characterizing Mutation and Selection from Trees

Beyond tree topology, B cell phylogenies are used to quantify selection pressures. A key metric is the ratio of replacement-to-silent mutations (R/S) in the framework regions (FWRs) and complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) [1] [2]. An R/S ratio significantly higher than the expected baseline in the CDRs is a strong indicator of positive selection for improved antigen binding. Conversely, negative selection to preserve structural integrity is indicated by low R/S ratios in the FWRs.

Phylogenetic trees also enable the reconstruction of ancestral sequences, including the unmutated common ancestor (UCA) of a lineage and intermediate variants [15] [1]. This is particularly valuable for vaccine design, as it allows researchers to trace the developmental pathway of a broadly neutralizing antibody and design immunogens that can initiate or steer similar pathways in a naive host [15].

Quantitative Insights and Data

The processes of clonal expansion and affinity maturation can be quantified through repertoire sequencing, revealing key statistical properties of immune responses.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Features of B Cell Clonal Expansion and Affinity Maturation

| Feature | Typical Value or Observation | Biological Significance / Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| SHM Rate | Up to 10â»Â³ per base per generation (1,000,000x background) [14] | Enables rapid generation of antibody variant diversity for selection. |

| Mutation Load in Mature Antibodies | Influenza: 5-10% from germline [15]HIV broadly neutralizing antibodies: 15-30% from germline [15] | Reflects the extent of selection pressure and number of cycles required for protection; highly mutated antibodies often indicate a long co-evolution with a rapidly evolving pathogen. |

| Clone Size Distribution | Long-tailed, following a power-law distribution [18] | A few clones expand massively (immunodominance), while many clones remain small. |

| Memory B Cell Diversity | Higher diversity and lower antigen specificity than plasma cells [18] | Suggests a strategy to maintain a broad repertoire for protection against future, variant pathogens. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

This section outlines detailed methodologies for two critical experiments in B cell repertoire research.

Protocol: B Cell Receptor Repertoire Sequencing and Clonal Lineage Analysis

Objective: To sequence the BCR repertoire from an immune tissue or cell population, identify clonally related sequences, and reconstruct their phylogenetic relationships [1] [19].

Sample Preparation & Single-Cell Sorting:

- Isolate mononuclear cells from tissue (e.g., lymph node, spleen, blood) using density gradient centrifugation.

- Stain cells with fluorescently labeled antibodies against B cell surface markers (e.g., CD19, CD20) and other differentiation markers (e.g., CD27 for memory B cells).

- Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to sort desired B cell populations (e.g., naive, memory, plasma cells) into 96-well plates or prepare a single-cell suspension for droplet-based sequencing.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- For plate-based methods: Perform reverse transcription and PCR amplification of IgH and IgL genes using nested, multiplexed V-gene primers.

- For droplet-based methods (e.g., 10X Genomics): Use a commercial solution that captures poly-adenylated RNA, including BCR transcripts, within oil droplets containing barcoded beads.

- Sequence the amplified libraries on a high-throughput platform (Illumina MiSeq/NextSeq) to achieve sufficient depth and read length for V(D)J analysis.

Computational Analysis:

- Pre-processing & Error Correction: Use pRESTO or the 10X Cell Ranger pipeline to quality-filter reads, correct sequencing errors, and assemble full-length V(D)J sequences.

- Germline Alignment & Clonal Clustering: Align sequences to IMGT germline references using IgBLAST. Group sequences into clones based on shared V and J genes and highly similar CDR3 nucleotide sequences using SCOPer or Partis.

- Phylogenetic Tree Building: For each clone, perform multiple sequence alignment and reconstruct a phylogenetic tree using a maximum likelihood (IgPhyML) or maximum parsimony (GCTree) method, with the inferred germline sequence as the root.

- Selection Analysis: Calculate the R/S ratio in the FWR and CDR using tools like BASELINe or ShazaM to infer antigen-driven selection.

Protocol: In Vitro Affinity Maturation via Phage Display

Objective: To artificially evolve an antibody fragment to higher affinity for a target antigen through iterative rounds of mutagenesis and selection [14] [15].

Library Generation:

- Start with a gene encoding the antibody variable region of interest (e.g., a scFv or Fab).

- Introduce random mutations into the CDRs using error-prone PCR or by using synthetic oligonucleotides for DNA shuffling.

- Clone the diversified library into a phage display vector, creating a fusion between the antibody fragment and a phage coat protein.

Panning and Selection:

- Incubate the phage library with immobilized target antigen.

- Wash away unbound and weakly binding phage particles with increasingly stringent conditions.

- Elute the specifically bound phages, typically by lowering pH or using a competitive ligand.

- Infect E. coli with the eluted phages to amplify the selected pool for the next round.

Screening and Characterization:

- After 3-4 rounds of panning, isolate individual clones and express their antibody fragments.

- Screen clones for improved antigen binding using ELISA or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to quantify binding affinity (KD).

- Sequence the variable regions of high-affinity binders to identify the key mutations responsible for improvement.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for B Cell Repertoire and Affinity Maturation Research

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Sequencing Platforms | 10X Genomics Chromium, BD Rhapsody | Enables paired heavy- and light-chain BCR sequencing from thousands of individual B cells. |

| BCR Sequence Analysis Software | Cell Ranger, IgBLAST, MiXCR | Processes raw sequencing data, performs V(D)J alignment, and annotates mutations. |

| Clonal Clustering Tools | SCOPer, Partis | Groups BCR sequences into clonal lineages based on shared ancestry. |

| Phylogenetic Tree Building Software | IgPhyML, GCTree, Alakazam | Reconstructs evolutionary trees of B cell clones to trace mutation history and selection. |

| In Vitro Display Technologies | Phage display, Yeast display | Platforms for screening antibody libraries for high-affinity binders through iterative selection. |

| Activation-Induced Deaminase (AID) | N/A | The key enzyme that initiates somatic hypermutation by deaminating cytosine in antibody genes. |

| Alvimopan | Alvimopan, CAS:156053-89-3, MF:C25H32N2O4, MW:424.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Avobenzone | Avobenzone | High-purity Avobenzone (Butyl Methoxydibenzoylmethane), a broad-spectrum UVA absorber. For research use only. Not for human consumption. |

Applications in Immunology and Drug Development

The principles of clonal expansion and affinity maturation are directly applied in biotechnology and medicine.

- Vaccine Design: By isolating broadly neutralizing antibodies from infected individuals and using phylogenetic analysis to reconstruct their developmental pathways, researchers can design sequential immunogens that "guide" the affinity maturation process in naive individuals towards a desired, protective antibody response [15]. This is a key strategy for vaccines against rapidly evolving viruses like HIV and influenza.

- Therapeutic Antibody Engineering: In vitro affinity maturation is a standard industry practice for optimizing therapeutic antibody candidates. Techniques like phage display and yeast display mimic the natural process by creating diverse antibody libraries and applying stringent in vitro selection to isolate variants with picomolar affinities and improved biophysical properties [14] [17].

- Understanding Autoimmunity and Cancer: Aberrant clonal expansion and SHM can contribute to disease. Phylogenetic analysis of BCR repertoires can identify expanded, pathogenic clones in autoimmune conditions or B-cell lymphomas, providing insights into disease mechanisms and potential targets for therapy [16] [1].

Germinal centers (GCs) are transient, specialized microenvironments that form within secondary lymphoid organs, such as lymph nodes and the spleen, following exposure to an antigen. They are the primary sites where B cells undergo affinity maturation, a Darwinian evolutionary process that optimizes the antibody response [20]. Within GCs, B cells undergo iterative cycles of proliferation, somatic hypermutation (SHM) of their immunoglobulin genes, and selection based on antigen-binding affinity. This process results in the production of B cells expressing antibodies with significantly increased affinity for the initiating antigen, and their differentiation into long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells, which are fundamental to durable humoral immunity and vaccine efficacy [20] [21]. Understanding the evolutionary dynamics within GCs is not only crucial for fundamental immunology but also for advancing therapeutic goals, such as the design of vaccines against difficult-to-neutralize viruses [20]. This whitepaper delves into the core mechanisms, quantitative dynamics, and state-of-the-art methodologies used to dissect GCs as sophisticated in vivo evolution machines, framing the discussion within the context of phylogenetic analysis of B-cell repertoire evolution.

Core Evolutionary Mechanisms in the Germinal Center

The GC reaction is spatially organized into two primary functional zones: the dark zone (DZ) and the light zone (LZ). B cells continuously cycle between these zones, with each cycle refining the antibody population.

The Dark Zone: Proliferation and Diversification

In the DZ, B cells undergo rapid clonal expansion. Critically, this proliferation is coupled with somatic hypermutation (SHM), an enzymatic process that introduces point mutations into the variable regions of immunoglobulin genes at a remarkably high rate [21]. Traditionally, SHM was believed to occur at a fixed rate of approximately (1 \times 10^{-3}) per base pair per cell division. However, recent research challenges this paradigm, suggesting the rate is regulated.

The Light Zone: Selection Based on Fitness

Following mutation and division, B cells migrate to the LZ. Here, they encounter a critical bottleneck. They must compete for two scarce resources:

- Antigen: Displayed as immune complexes on the surface of follicular dendritic cells (FDCs).

- T Cell Help: Signals from T follicular helper (Tfh) cells [21].

B cells that have acquired mutations allowing their B cell receptors (BCRs) to bind antigen with higher affinity are more successful at internalizing antigen and presenting it to Tfh cells. This successful presentation secures pro-survival and pro-proliferative signals, determining which B cells are selected to re-enter the DZ for further rounds of mutation and expansion or to exit the GC as plasma cells or memory B cells [21]. This iterative process of random mutation followed by affinity-based selection is the engine of affinity maturation.

The following diagram illustrates this cyclic process of evolution within the germinal center.

Quantitative Dynamics of GC Evolution

A central, unresolved question in GC biology has been the precise mathematical relationship between BCR affinity and cellular fitness—termed the "affinity-fitness response function." A landmark study used simulation-based deep learning to infer this function from a unique "replay" experiment in mice, where all GCs were seeded by genetically identical B cells [20] [22].

The Affinity-Fitness Relationship

The research quantified how the intrinsic birth rate of a B cell (its fitness in the absence of constraints) changes with its affinity. The inferred response function is not linear but demonstrates a sharp increase, as summarized below.

Table 1: Inferred Affinity-Fitness Response Function [20] [22]

| Affinity State | Relative Intrinsic Birth Rate (Fitness) |

|---|---|

| Naive (Affinity 0) | 1x (Baseline) |

| Intermediate (Affinity 1) | ~3x Baseline |

| High (Affinity 2) | ~9x Baseline |

This finding means a B cell that acquires a mutation conferring an intermediate affinity advantage early in the GC reaction would replicate approximately three times faster than its peers, granting it a significant selective advantage [20] [22].

Regulation of Somatic Hypermutation

To protect high-affinity lineages from the detrimental effects of random mutations, GCs employ a sophisticated regulatory mechanism for SHM. Experimental data from mice immunized with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines or a model antigen show that B cells receiving strong Tfh signals undergo more cell divisions but paradoxically exhibit a lower mutation rate per division [21].

Table 2: Mutation Probability per Division Based on Tfh Cell Help [21]

| Number of Divisions (D) Programmed by Tfh Help | Mutation Probability per Division (p_mut) |

|---|---|

| D = 1 | 0.6 |

| D = 6 | 0.2 |

This affinity-dependent dampening of SHM safeguards high-affinity B cell lineages. In simulations, a constant mutation rate (pmut=0.5) for a B cell dividing six times produced an average of only 27 progeny, with over 40% having lower affinity than the parent. In contrast, a decreasing pmut yielded an average of 41 progeny, with only 22% exhibiting lower affinity, thereby enhancing the clonal expansion of high-affinity variants without generational "backsliding" [21].

Advanced Methodologies for Deconstructing GC Dynamics

The "Replay" Experiment and Simulation-Based Inference

To quantitatively dissect GC evolutionary parameters, researchers developed a "replay" experimental system. This uses engineered mice where all naive B cells seeding GCs carry the same pre-rearranged BCR genes, ensuring an identical starting point for affinity maturation [20] [22]. The experimental and computational workflow is complex, integrating data from multiple sources to infer the underlying evolutionary dynamics.

The following diagram outlines the key steps in this sophisticated inference pipeline.

Protocol Overview:

- Experimental Data Generation: Individual GCs are extracted from immunized mice at specific time points (e.g., 15 or 20 days post-immunization), and BCR sequences from single cells are obtained [20] [22].

- Phylogenetic Analysis: For each GC, a phylogenetic tree is reconstructed from the BCR sequences using tools like IQ-TREE, with the known naive sequence as an outgroup. Ancestral sequence reconstruction is performed for all internal nodes [20] [22].

- Affinity Annotation: A pre-existing deep mutational scan (DMS) of the naive antibody sequence is used to map each observed mutation (and combinations thereof) to a quantitative affinity value. This maps affinity onto every node of the phylogenetic tree [20].

- Simulation-Based Inference (SBI): A birth-death model of GC dynamics is simulated, where birth rates are a function of the affinity-fitness response function. Since the likelihood for this complex model is intractable, deep learning and SBI techniques are used to find the parameters of the response function that produce phylogenetic trees most closely matching the observed data [20] [22].

3D Spatial Imaging of Whole Lymph Nodes

Understanding the spatial context of GC evolution is vital. A recent protocol enables rapid, high-resolution, multicolor 3D imaging of whole immunized mouse lymph nodes using light sheet fluorescence microscopy [23].

Protocol Overview: [23]

- Immunization & Harvesting: Mice are immunized subcutaneously. After 7-35 days, lymph nodes are harvested and fixed.

- Staining & Clearing: Fixed lymph nodes undergo permeabilization, followed by multiplexed antibody staining (e.g., for Bcl6+ GC B cells, CD3+ T cells, CD138+ plasma cells, CD35/21+ FDCs). The tissue is then cleared to render it optically transparent.

- Image Acquisition & Analysis: Cleared whole lymph nodes are imaged using a light sheet microscope, capturing the entire 3D architecture in approximately 30 minutes. Analysis with software like Imaris allows for the segmentation and quantification of key immune subsets at single-cell resolution within their native spatial context [23].

Ecological Analysis of Tissue Spatial Organization

The MESA (Multiomics and Ecological Spatial Analysis) framework adapts concepts from ecology to quantitatively characterize cellular diversity and spatial organization in tissues using spatial-omics data [24]. It introduces metrics like the Multiscale Diversity Index (MDI) to quantify how cellular diversity changes across spatial scales, and identifies hot spots (clusters of high diversity) and cold spots (clusters of low diversity) [24]. Applying MESA to human tonsil data, for example, revealed distinct subniches within germinal centers that were not detected by conventional analysis methods, providing a more nuanced view of the GC microenvironment [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Germinal Center Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in GC Research | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| "Replay" Mouse Model | Provides a genetically identical B cell repertoire, enabling precise evolutionary studies by controlling for naive sequence variation. | Inference of affinity-fitness dynamics [20] [22]. |

| H2b-mCherry Reporter Mouse | Tracks cell division history in vivo via fluorescence dilution. Allows sorting of B cells based on division number. | Investigating the link between division count and SHM rate [21]. |

| Antibody Panels for Flow/CyTOF | Identifies and characterizes GC B cell, Tfh, and other immune populations based on surface and intracellular protein markers. | Phenotyping GC populations; isolating GC B cells for sequencing. |

| Single-Cell BCR Sequencing | Resolves clonal relationships and somatic mutations between B cells at the individual sequence level. | Phylogenetic tree reconstruction; SHM analysis [20] [21]. |

| Deep Mutational Scan (DMS) | Empirically measures the functional effect of all possible single mutations in an antibody on antigen binding. | Mapping BCR sequence to affinity for phylogenetic nodes [20]. |

| Multiplex Antibody Panels for Imaging | Enables simultaneous detection of multiple cell types and structures in fixed tissue (e.g., B cells, T cells, FDCs). | 3D spatial analysis of GC architecture and cellular neighborhoods [23] [24]. |

| SBI Software (e.g., gcdyn) | Open-source computational tools for performing simulation-based inference on phylogenetic trees from GCs. | Inferring evolutionary parameters like the affinity-fitness function [20]. |

| Awl 60 | Awl 60, CAS:140716-14-9, MF:C57H65N9O8S, MW:1036.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Amebucort | Amebucort, CAS:83625-35-8, MF:C28H40O7, MW:488.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Affinity maturation in germinal centers (GCs) relies on somatic hypermutation (SHM) to generate high-affinity antibodies. A fundamental challenge arises during rapid, large-scale clonal expansions ("clonal bursts"), where the high rate of cell division could lead to an accumulation of deleterious mutations, compromising antibody affinity. This whitepaper details a mechanism identified in a 2025 Nature study: the transient suppression of SHM during proliferative bursts. We summarize the quantitative evidence supporting this model, describe the key experimental protocols, and contextualize its significance for phylogenetic analysis of B-cell receptor (BCR) repertoires and therapeutic antibody development [25] [26] [27].

In the germinal center, B cells undergo cycles of mutation and selection. Somatic hypermutation (SHM), catalyzed by activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), introduces point mutations into immunoglobulin genes at an estimated rate of ~10â»Â³ per base pair per cell generation [25] [27]. While this process is essential for affinity maturation, the random nature of SHM means deleterious mutations outnumber beneficial ones.

This creates a specific problem during clonal bursts – rapid, large-scale expansions of a single B cell clone. These bursts are driven by strong proliferative signals from T follicular helper cells and involve multiple rounds of cell division in the absence of affinity-based selection. Under a constant SHM rate model, such rapid proliferation would inevitably lead to the accumulation of deleterious mutations in a majority of the progeny, precipitating a decline in average affinity across the clone. The discovery of a mechanism to transiently silence hypermutation resolves this apparent contradiction, revealing a sophisticated layer of regulation in GC dynamics [25] [27].

Core Discovery and Quantitative Evidence

The central finding is that GC B cells actively downregulate SHM during clonal-burst-type expansion. This ensures a large fraction of the progeny retains the ancestral, high-affinity genotype, preserving affinity in the absence of selection [25].

Phylogenetic Analysis of Clonal Bursts

The study employed the gctree algorithm to build mutational phylogenies from B cells isolated from single-colored GCs in AID-Brainbow mice.

Table 1: Analysis of Parental Node Size in Clonal Burst Phylogenies

| Germinal Center (GC) | Estimated Total Cells in Clone | Number of Sequenced Cells | Fraction of Parental-Type Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC i | ~2,000 | 45 | 0.27 |

| GC ii | ~2,000 | 56 | 0.32 |

| GC iii | ~2,000 | 42 | 0.45 |

| GC iv | ~2,000 | 38 | 0.21 |

| GC xi | ~2,000 | 41 | 0.11 |

| Average (12 GCs) | ~2,000 | - | 0.32 ± 0.14 |

The data show that a significant proportion of cells in a burst (average of 32%) are genetically identical, forming a large "parental node" in the phylogeny. This is incompatible with a constant, high SHM rate [25].

Birth-Death Simulations to Estimate SHM Rate

The researchers used birth-death process simulations to determine the SHM rate that would best reproduce the observed phylogenetic structures.

Table 2: Comparison of SHM Rates from Simulation vs. Literature

| SHM Rate Scenario | Mutation Probability (per Ighv region per daughter cell) | Equivalent Mutation Rate (per 10³ bases per generation) |

|---|---|---|

| Previously Established Average | ~0.33 | ~1.0 |

| Inferred from Clonal Burst Phylogenies | 0.10 (range: 0.043 - 0.16) | 0.30 (range: 0.13 - 0.46) |

These simulations demonstrated that the observed phylogenies are only consistent with an SHM rate that is one-half to one-eighth of the previously established average for GC B cells, confirming strong downregulation of SHM during bursts [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The discovery was achieved through a combination of in vivo models, imaging, and computational biology.

In Vivo Mouse Model and GC Isolation

- Genetic Model: AicdaCreERT2/+.Rosa26Confetti/Confetti (AID-Brainbow) mice for multicolour fate-mapping of B cell clones [25].

- Immunization: Mice were immunized with chicken IgY in alum adjuvant to form GCs.

- Clonal Burst Identification: Popliteal lymph nodes were scanned for single-coloured GCs with a normalized dominance score (NDS) > 0.5 at days 17 or 21 post-immunization.

- Single-Cell Sequencing: B cells from identified GCs were isolated via microdissection, and their Ighv genes were sequenced. The unmutated germline sequence was used to root the phylogenetic trees [25] [1].

Intravital Imaging and Cell Cycle Analysis

- CDK2 Activity Reporter: A mouse strain carrying a reporter for cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) activity was used.

- Image-Based Cell Sorting: B cells actively undergoing proliferative bursts were identified and sorted based on their CDK2 activity profile.

- Key Finding: Bursting B cells were found to lack the transient CDK2low 'G0-like' phase of the cell cycle. Since SHM is linked to this phase, its absence results in the transient silencing of hypermutation during rapid cycling [25].

Phylogenetic Tree Construction and Analysis

- Data Processing: BCR sequences were aligned to germline V(D)J reference databases using tools like IgBLAST or IMGT/V-QUEST. Sequences were then grouped into clones based on similarity using statistical inference tools [1].

- Tree Building: Mutational phylogenies for each clone were built using the

gctreealgorithm, which can utilize sequence abundance data to improve accuracy. The germline sequence was used to root the tree [25] [1]. - Simulation & Modeling: A birth-death process simulation was used to model clonal expansion under different SHM rate parameters. The simulated outcomes were statistically compared to the empirical phylogenetic data to infer the most likely in vivo SHM rate [25].

Diagram 1: Mechanism of SHM regulation during standard cycling versus clonal bursting. Bursting cells skip the G0-like phase where SHM occurs, delaying mutation until after proliferation [25] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

This research relied on several critical reagents and computational tools, which are also essential for scientists aiming to replicate or build upon these findings.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Reagent / Tool Name | Function / Application in the Study | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|

| AID-Brainbow Mouse Model (AicdaCreERT2/+.Rosa26Confetti/Confetti) | In vivo fate-mapping of B cell clones; enables visual identification of clonal bursts. | Critical for linking cellular phylogeny to spatial organization in GCs. |

| CDK2 Activity Reporter | Live imaging and sorting of B cells based on cell cycle phase (G0-like vs. inertial cycling). | Directly linked SHM suppression to the absence of the CDK2low phase. |

| Ccnd3T283A Mutant Mouse | Models Burkitt-lymphoma-associated mutation; increases inertial cycling to test SHM rate. | Provided genetic evidence that increased divisions did not increase mutations. |

| gctree Algorithm | Phylogenetic tree building from BCR sequences, using sequence abundance data. | Enabled accurate reconstruction of mutational phylogenies from burst clones. |

| Birth-Death Simulation Model | Computational framework to infer SHM rates by comparing simulated vs. observed phylogenies. | Provided quantitative, model-based evidence for reduced SHM rates. |

| IgBLAST / IMGT V-QUEST | Bioinformatics tools for aligning BCR sequences to germline V, D, J genes. | Essential first step for accurate phylogenetic analysis and mutation calling [1]. |

| Amelubant | Amelubant, CAS:346735-24-8, MF:C33H34N2O5, MW:538.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Amiquinsin | Amiquinsin, CAS:13425-92-8, MF:C11H12N2O2, MW:204.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for B-Cell Phylogenetics and Repertoire Analysis

The phenomenon of transient SHM silencing has profound implications for how we interpret B cell phylogenetic trees and repertoire data.

- Tree Topology Interpretation: The presence of large polytomies (nodes with many identical sequences) in a phylogeny may not indicate simultaneous divergence but rather a period of rapid, mutation-free expansion. Analytical tools must account for this possibility to avoid misinterpretation [25] [28].

- Affinity Maturation Models: Models of affinity maturation must be updated to include phases of variable mutation rates. The SHM rate is not a fixed parameter but a dynamically regulated variable, fine-tuned by cell cycle kinetics and T cell help [27] [20].

- Candidate Antibody Selection: In antibody discovery workflows, phylogenetic trees are used to select candidates. Understanding that cells in a large, dominant clade may have undergone a burst with suppressed SHM highlights that the ancestral node sequence might be a high-value candidate, as it is preserved in many progeny [28].

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow from in vivo modeling to computational validation, illustrating the multi-disciplinary approach required for this discovery [25].

The discovery that B cells transiently silence hypermutation during clonal bursts represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of germinal center biology. It resolves the long-standing dilemma of how affinity is preserved during rapid expansion and reveals cell cycle modulation as a key regulatory layer controlling SHM.

For researchers in phylogenetics and drug development, this insight provides a new framework for analyzing BCR repertoire data. It suggests that therapeutic strategies, including vaccine design, could aim to modulate not only the selection of B cells but also the timing and rate of their mutation, potentially leading to more robust and high-affinity antibody responses [27]. Future work will focus on elucidating the precise molecular signals that control this inertial cycling and how these mechanisms vary across different immune challenges.

From Data to Discovery: Methods and Workflows for B-Cell Lineage Tracing

The adaptive immune system generates a formidable diversity of B-cell receptors (BCRs) to recognize and neutralize a vast spectrum of pathogens [29] [30]. This diversity originates from two primary mechanisms: V(D)J recombination, which randomly assembles gene segments to create a naive BCR, and somatic hypermutation (SHM), which introduces point mutations into the BCR genes of antigen-activated B cells during affinity maturation [29] [31]. A clonal family (CF) is defined as the collective group of B cells originating from a single, unique V(D)J rearrangement event and subsequently diversified through SHM [29] [30]. Delimiting these clonal families from high-throughput sequencing data is the foundational step upon which all subsequent analysis of B-cell repertoire evolution, dynamics, and function is built [32] [31]. Without accurate family delineation, the interpretation of immune responses—from the identification of broadly neutralizing antibodies to the understanding of autoimmune diseases—becomes fundamentally compromised.

The Biological and Analytical Imperative

The process of B-cell activation and differentiation creates a natural evolutionary tree within an organism. Upon binding its cognate antigen, a naive B cell proliferates, and its progeny undergo SHM, forming a lineage of related cells [29]. Identifying these lineages is crucial because sequences within a clonal family, sharing a common ancestral B cell, are not statistically independent and must be analyzed collectively [29] [30].

Accurate clonal family delimitation enables researchers to:

- Infer Antigen-Driven Expansion: Identify which B-cell clones have expanded in response to antigenic challenge, pinpointing the immune system's active targets [30].

- Quantify Affinity Maturation: Track the patterns of somatic hypermutation within a lineage to study the process of selection for higher-affinity antibodies [29] [31].

- Reconstruct Phylogenetic Lineages: Build mutational trees and networks to understand the evolutionary history and relationships between B cells in a response [33].

- Discover Therapeutic Antibodies: Identify and trace the development of antibodies with desired properties, such as broad neutralization against viruses like HIV or SARS-CoV-2 [29] [34].

Methodological Landscape: Strategies for Delimitation

A range of computational methods has been developed to solve the clonal family inference problem, each with distinct strategies and requirements. They can be broadly categorized by their reliance on a reference genome and their underlying algorithmic approach.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Clonal Family Delimitation Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Requires Germline Reference? | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change-O | Groups sequences by V/J genes and junction region similarity using a defined threshold [29] [30]. | Yes [29] [30] | Often used with a 0.15 dissimilarity threshold for human repertoires [29]. |

| SCOPer-H | Hierarchical method using a user-defined, global threshold for junction region similarity [29] [30]. | Yes [29] [30] | An implementation of the Change-O threshold approach [29]. |

| SCOPer-S | Spectral clustering that adaptively calculates the optimal similarity cutoff for each V-J group [29] [30]. | Yes [29] [30] | Accounts for variation in SHM rates across different clonal families [30]. |

| MiXCR | Aligns sequences to a reference genome and assembles clonotypes based on identical or similar user-defined features [29] [30]. | Yes [29] [30] | Tolerates PCR and sequencing errors through fuzzy matching [29] [30]. |

| mPTP | Phylogenetic species delimitation method applied to a tree of all B-cell sequences to identify clonal families [29] [30]. | No [29] [30] | Infers families from branching patterns, ideal for non-model organisms [29]. |

| HILARy | Combines probabilistic models of V(D)J recombination with clustering, leveraging CDR3 distances and shared mutations [31]. | Implied | Designed for both speed and accuracy on large-scale datasets; uses "VJl" classes [31]. |

| AntibodyForests | Infers mutational networks and phylogenetic trees for pre-defined clonal lineages [33]. | Flexible | A tool for intra-clonal analysis post-delimitation, supporting multiple tree-building algorithms [33]. |

The Central Challenge of the CDR3

The complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) is the most variable part of the BCR, encompassing parts of the V and J genes, the entire D gene, and junctional insertions and deletions [29] [30]. Its hypervariability makes it a strong fingerprint for a specific V(D)J recombination event, as it is highly unlikely for two independent recombination events to produce identical or highly similar CDR3 sequences [31]. Consequently, most methods initiate clustering by grouping sequences that share the same V gene, J gene, and CDR3 length (a "VJl" class) before performing finer-grained clustering within these groups based on nucleotide or amino acid similarity [31].

Performance Benchmarks and Comparative Evaluations

Given the critical nature of this first step, systematic evaluations have been conducted to assess the performance of different methods. A comprehensive study applying eight different inference approaches to multiple datasets found that while most methods perform similarly, factors like sequencing depth and mutation load significantly impact reconstruction [32]. The study concluded that Change-O best reproduced the true CF structure in simulations, and that more complex methods do not necessarily outperform simpler ones [32].

Another evaluation focusing on phylogenetic methods demonstrated that the mPTP method, which uses a phylogenetic tree to delimit clones, had lower error rates than several immunology-specific tools in the absence of a complete reference genome [30]. This highlights mPTP as a powerful alternative for studying antibody evolution in non-model organisms [30]. Meanwhile, SCOPer-H consistently yielded superior results in simulations that assumed a good reference germline assembly was available [30].

Table 2: Relative Performance Characteristics of Methods

| Method | Reported Strengths | Reported Limitations / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Change-O | Best reproduces true CF structure in simulations [32]. | Performance depends on chosen threshold [29] [32]. |

| SCOPer-H | Top performer when a good germline reference is available [30]. | Relies on a reference genome; less suitable for non-model systems [29] [30]. |

| SCOPer-S | Accounts for variable SHM rates across families [30]. | Performance similar to other methods in some evaluations [32]. |

| mPTP | Competitive performance without a reference genome; lower error rates than some immunology-specific tools [29] [30]. | Requires building a phylogenetic tree of all sequences [29] [30]. |

| HILARy | Achieves high precision and sensitivity; efficient on large datasets [31]. | -- |

| Alignment-Free | Does not require a reference genome. | Underperformed relative to other methods in a prior study [29]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Implementing HILARy

The HILARy method provides a robust, two-algorithm approach for clonal family inference. The following protocol is adapted from its description for use with IgH sequence data [31].

Preprocessing and Initial Data Partitioning

- Sequence Quality Control and Alignment: Process raw sequencing reads through a tool like pRESTO to perform quality filtering, demultiplexing, and merging of paired-end reads. Align the resulting high-quality sequences to a database of V and J germline gene references using IgBLAST to assign gene calls and define the CDR3 regions.

- Define

VJlClasses: Partition the aligned sequences into distinct subsets, or "VJl" classes, where all sequences within a subset share the same assigned V gene, J gene, and CDR3 nucleotide lengthl[31]. This drastically reduces the number of pairwise comparisons needed.

Core Clustering with HILARy-CDR3

- Estimate Positive Pair Prevalence: For each

VJlclass, model the distribution of pairwise CDR3 nucleotide Hamming distances. Fit this distribution as a mixture model to estimateÏ, the prevalence of truly clonally related ("positive") pairs [31]. - Determine Length-Dependent Threshold: Using the estimated

Ïand the CDR3 lengthl, calculate a clustering threshold. This threshold is tuned to achieve a desired precision (e.g., 99%) by leveraging precomputed distributions of distances for both related and unrelated pairs, the latter generated using a probabilistic model of V(D)J recombination like soNNia [31]. - Single-Linkage Clustering: Within the

VJlclass, perform single-linkage clustering on the sequences based on their pairwise CDR3 Hamming distances, using the calculated threshold. Any two sequences with a distance below the threshold are linked and grouped into the same preliminary clonal family.

Refinement with HILARy-Full

- Identify Ambiguous Clusters: Flag clusters that contain sequences with a large range of mutations or that have a high internal variance in mutation count for further analysis.

- Exploit Phylogenetic Signal: For sequences within these ambiguous clusters, perform a multiple sequence alignment of the entire V(D)J region. Construct a phylogenetic tree or use a statistical test to identify pairs of sequences that share an unlikely number of common mutations outside the CDR3, providing strong evidence for clonal relatedness [31].

- Merge Clusters: Merge preliminary clusters that are connected by these statistically supported shared mutations to form the final, refined clonal families.

Visualizing Workflows and Lineages

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical relationship of the clonal delimitation process and the resulting lineage structures.

Clonal Family Delimitation Workflow

B-Cell Lineage Tree Structure

Successful clonal family analysis relies on a suite of software tools and curated biological databases.

Table 3: Key Resources for Clonal Family Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Delimitation |

|---|---|---|

| IgBLAST | Software Tool | The standard for aligning BCR sequences to V, D, and J germline gene references, providing essential gene calls and CDR3 definitions [29] [30]. |

| IMGT/HighV-QUEST | Web Tool / Database | A highly curated online system for immunoglobulin sequence alignment and annotation, serving as a key alternative to IgBLAST [29] [30]. |

| Change-O & SCOPer | Software Suite | A comprehensive toolkit for post-alignment analysis; Change-O handles initial grouping, while SCOPer performs hierarchical or spectral clustering [29] [32] [30]. |

| Immcantation Portal | Software Framework | Provides a standardized pipeline for repertoire analysis, integrating tools like Change-O and SCOPer for an end-to-end workflow [29]. |

| MiXCR | Software Tool | An integrated pipeline that performs alignment, assembly, and clonotyping of repertoire sequencing data [29] [30]. |

| AntibodyForests | R Package | Infers and analyzes phylogenetic trees and networks for pre-defined clonal lineages, enabling deep intra-clonal evolutionary study [33]. |

| IMGT Gene Database | Biological Database | The international reference for immunoglobulin germline gene sequences, essential for accurate alignment and annotation [29]. |

Clonal family delimitation is more than a preliminary bioinformatic step; it is the process that transforms a disorganized collection of BCR sequences into biologically meaningful lineages. The choice of method—whether a reference-dependent tool like SCOPer-H for model organisms or a phylogenetically-aware tool like mPTP for non-model systems—has a profound impact on all downstream biological interpretations [32] [30]. As repertoire sequencing scales to ever-greater depths and single-cell resolution, the continued development and rigorous benchmarking of accurate, robust, and efficient delimitation algorithms will remain essential for unlocking the secrets of adaptive immunity.

The adaptive immune system's capacity to evolve is epitomized by the complex phylogenetic landscape of B-cell receptors (BCRs). Analyzing the evolution of B-cell repertoires requires sophisticated computational tools that can reconstruct clonal lineages, infer phylogenetic relationships, and quantify somatic hypermutation (SHM). Within this research domain, three reference-based frameworks have become foundational: the comprehensive MiXCR platform, the Change-O toolkit for advanced BCR analysis, and the broader Immcantation framework that encompasses both. These tools enable researchers to process high-throughput sequencing data, from raw reads to biologically meaningful phylogenetic trees, tracing the evolutionary history of B-cell clones in response to infection, vaccination, and autoimmunity. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of these tools, detailing their methodologies, applications, and implementation for B-cell repertoire evolution research.

Functional Capabilities and Performance

The selection of an appropriate tool is critical and must be guided by experimental design, data type, and research objectives. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and primary applications of MiXCR, Change-O, and the Immcantation framework.

Table 1: Core Functional Overview of B-Cell Repertoire Analysis Tools

| Tool / Framework | Primary Function | Key Strengths | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MiXCR [35] [36] [37] | End-to-end clonotype analysis & lineage tracing | High speed, comprehensive all-in-one tool, superior accuracy, user-friendly presets | Large-scale bulk and single-cell repertoire studies, rapid profiling, allele discovery |

| Change-O [38] [39] | Downstream analysis of pre-aligned data | Specialized utilities for clonal grouping, lineage tree building, and diversity analysis | Advanced phylogenetic analysis and hypothesis testing on defined clonotype sets |

| Immcantation [40] [39] | Framework for adaptive immune repertoire analysis | Modular, open-source ecosystem; integrates Change-O, Dowser, and pRESTO | Flexible, customizable pipelines for in-depth B-cell immunology research |

Beyond core functionalities, performance metrics such as processing speed and accuracy are paramount for large-scale studies. Independent benchmarking reveals significant differences.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of V(D)J Analysis Tools (Adapted from [35])

| Performance Metric | MiXCR | Immcantation | TRUST4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Processing Time (20M reads) | ~2 hours | >10 hours | Not specified |

| Relative Speed | Fastest (up to 6x faster) | Slowest | Intermediate |

| Sensitivity (on simulated data) | Highest, robust to errors | Lower | Lower |

| False Positives (Hybridoma Test) | Minimal clones identified | 100-200x more than MiXCR | ~20x more than MiXCR |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

MiXCR Protocol for B-Cell Lineage Tracing

The following protocol outlines a complete workflow for B-cell lineage tracing from raw sequencing data using MiXCR, including allele inference to improve phylogenetic accuracy [36].

Upstream Analysis and QC: Process raw FASTQ files using the

analyzecommand with a preset for the specific sequencing kit.Generate quality control reports to assess alignment rates and UMI coverage.

Personalized Allele Inference: Infer individual-specific alleles to distinguish true germline variants from somatic hypermutations, which is critical for accurate lineage tree reconstruction.

Clonotype Export and Lineage Tree Reconstruction: Export the refined clonotypes and reconstruct somatic hypermutation lineage trees.

Immcantation Protocol for Single-Cell BCR Analysis

This protocol uses the Immcantation Docker image to define clonal families and build lineage trees from 10x Genomics single-cell BCR data [39].

Data Preprocessing with IgBLAST: Generate AIRR-compliant rearrangement data from Cell Ranger output files.

R-Based Downstream Analysis: Load the required R libraries and the AIRR data for analysis.

Clonal Grouping and Lineage Tree Construction: Use the

dowserpackage to define clones and build phylogenetic trees.

Workflow Visualization and Experimental Setup

End-to-End Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of a complete B-cell repertoire phylogenetic analysis, from raw data to biological insight, integrating steps common to both MiXCR and Immcantation protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of B-cell repertoire phylogenetic studies relies on a suite of wet-lab and computational reagents. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for B-Cell Repertoire Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial BCR-seq Kits [36] | Library preparation with optimized primers for IG genes | MiLaboratories Human IG RNA Multiplex kit for bulk BCR sequencing |

| 10x Genomics Single Cell Immune Profiling [37] [39] | Simultaneous capture of paired-chain BCR sequences and cell barcodes | Linking BCR clonotype to cell phenotype in single-cell studies |

| Reference Germline Libraries [41] | Curated databases of V/D/J gene alleles for sequence alignment | IMGT database; MiXCR's built-in curated library with continuous updates |

| Docker Container Images [39] | Pre-configured computational environments for reproducible analysis | Immcantation Lab Docker image for a seamless setup of the full framework |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies [34] | Cell sorting and immunophenotyping (e.g., anti-IgG, -IgA, -IgM) | Isolating specific B-cell populations (e.g., memory B cells) pre-sequencing |

| Antrafenine | Antrafenine, CAS:55300-30-6, MF:C30H26F6N4O2, MW:588.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Arbaclofen Placarbil | Arbaclofen Placarbil|GABA-B Receptor Agonist|For Research | Arbaclofen Placarbil is a prodrug of R-baclofen, a selective GABA-B receptor agonist. This product is for Research Use Only and not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Implementation and Best Practices

Computational Environment and Data Considerations

For researchers implementing these pipelines, setting up an efficient computational environment is the first critical step. The Immcantation framework is most easily deployed via its dedicated Docker image, which ensures version compatibility across all tools [39]. While MiXCR is available as a standalone Java application, its performance is optimized when allocated sufficient computational resources; benchmarking was performed on a server with 24 CPU cores and 128 GB of RAM [35].