Decoding Human CD8+ T Cell Heterogeneity: A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Atlases and Their Applications in Biomedical Research

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our understanding of CD8+ T cell biology, revealing an unprecedented degree of heterogeneity in health, aging, and disease.

Decoding Human CD8+ T Cell Heterogeneity: A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Atlases and Their Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our understanding of CD8+ T cell biology, revealing an unprecedented degree of heterogeneity in health, aging, and disease. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational discoveries of CD8+ T cell subsets, the latest computational methods for atlas construction and data projection, strategies for overcoming annotation challenges, and the validation of these findings across studies and species. By integrating insights from massive-scale integration studies, such as those leveraging deep-learning models like scAtlasVAE on over 1.1 million cells, and specialized projection tools like ProjecTILs, this guide serves as a roadmap for leveraging T cell atlases to advance biomarker discovery, prognostic modeling, and the development of novel immunotherapies.

Unveiling CD8+ T Cell Diversity: From Fundamental Subsets to Age-Related Remodeling

CD8+ T cells are fundamental components of adaptive immunity, coordinating the eradication of infected and malignant cells. Upon activation, a single naive CD8+ T cell can generate a diverse army of daughter cells, encompassing potent effectors and long-lived memory populations, but also dysfunctional exhausted cells in states of chronic antigen exposure. The precise characterization of these subsets—naive, effector, memory, and exhausted—is critical for advancing our understanding of protective immunity and developing novel immunotherapies for cancer and chronic infections. The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized this field, enabling the construction of high-resolution transcriptional atlases that define core cellular states and their functional relationships across human tissues. This technical guide synthesizes traditional immunology with cutting-edge single-cell genomics to provide a definitive reference on CD8+ T cell subsets, framed within the context of a broader thesis on human T cell atlas research.

Defining the Core CD8+ T Cell Subsets

CD8+ T cell subsets are historically categorized by surface receptor expression and functional capacity, but recent scRNA-seq studies have refined these classifications through unsupervised clustering of transcriptional profiles. The following table summarizes the defining features of the core subsets.

Table 1: Core CD8+ T Cell Subsets and Their Defining Characteristics

| Subset | Key Surface Markers | Key Transcriptional Markers | Primary Functions | Tissue Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive (N) | CD45RA+, CCR7+, CD62L+, CD27+, CD28+ [1] [2] | TCF7, SELL, CCR7 [3] | Immune surveillance; precursor to all other subsets | Blood, Secondary Lymphoid Organs [1] |

| Effector Memory (TEM) | CD45RA-, CCR7- [2] | CCL5, GZMB, GZMK [3] | Rapid cytokine production and cytotoxicity upon re-encounter with antigen | Non-lymphoid tissues, Blood [3] |

| Terminally Differentiated Effector (TEMRA) | CD45RA+, CCR7-, CD27-, CD28-, CD57+, KLRG1+ [2] | PRF1, NKG7 [3] | Powerful, immediate cytotoxicity | Enriched in bone marrow and blood [3] |

| Tissue-Resident Memory (TRM) | CD69+, CD103+ (ITGAE+) | CXCR6, ITGA1, ITGAE [3] | Long-term peripheral surveillance in barrier tissues | Mucosal sites (e.g., lung), Barrier tissues [3] |

| Progenitor Exhausted (Tpex) | PD-1+, TCF-1+ (TCF7+) | TCF7 [4] | Self-renewal; response to checkpoint blockade | Tumor Microenvironment, Chronic Infection [5] |

| Terminally Exhausted (Tex-term) | PD-1hi, TIM-3+, TIGIT+, CD39+ [6] | TOX [6] | Severely impaired function; high inhibitory receptor burden | Tumor Microenvironment, Chronic Infection [5] [6] |

The Differentiation Pathway: From Naive to Terminally Differentiated Cells

The journey of a CD8+ T cell from a naive state to a fully differentiated effector is a tightly regulated process. The following diagram illustrates the core differentiation pathway and the associated shifts in key surface markers, as defined by polychromatic flow cytometry and transcriptional profiling.

A Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Atlas of CD8+ T Cells

Single-cell transcriptomics has provided an unprecedented, high-dimensional view of CD8+ T cell states in health and disease, moving beyond blood to encompass key tissues like lung, lymph nodes, and bone marrow.

Key Findings from a Human Tissue T Cell Atlas

A landmark study profiling over 50,000 human T cells from blood, lung, lymph nodes, and bone marrow established a core reference map. Key findings include [3]:

- Conserved Activation States: scRNA-seq of resting and activated T cells revealed lineage-specific activation states conserved across all tissue sites. For CD8+ T cells, this included distinct effector states characterized by expression of cytotoxicity genes (GZMB, GZMK), and a separate population of terminally differentiated effector cells (TEMRA) expressing PRF1 and NKG7 [3].

- Tissue-Specific Signatures: A core tissue signature was identified, distinguishing tissue-derived T cells from their blood counterparts. This signature included genes associated with the cytoskeleton and cell matrix, suggesting an adaptation to the tissue microenvironment independent of the canonical tissue-resident memory (TRM) phenotype [3].

- Projection of Disease States: Comparing this healthy reference to tumor-associated T cells revealed a predominance of activated CD8+ T cell states that co-expressed markers of exhaustion, activation, and proliferation, highlighting the dysregulated state of T cells in cancer [3].

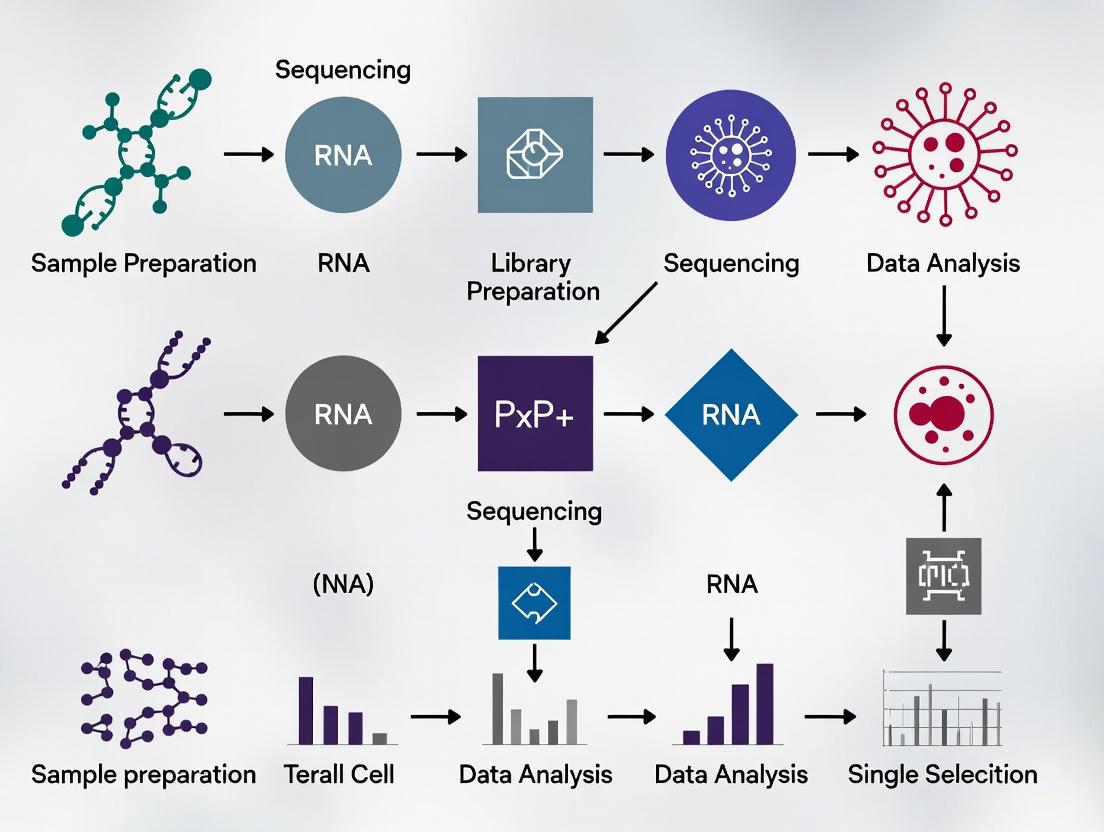

Experimental Workflow for scRNA-seq of Tissue T Cells

The following diagram outlines the comprehensive experimental workflow used to generate this human T cell atlas, from tissue processing to computational analysis.

The Exhausted CD8+ T Cell State in Chronic Disease

T cell exhaustion is a distinct differentiation state induced by persistent antigen exposure in chronic infections and cancer, characterized by hierarchical loss of effector functions and upregulation of inhibitory receptors [7].

Hallmarks and Heterogeneity of Exhausted T Cells

Exhausted CD8+ T cells are defined by several key features [7] [8]:

- Progressive Loss of Function: Cytokine production (e.g., IL-2, TNF, IFN-γ) and killing capacity are gradually lost.

- Upregulation of Inhibitory Receptors: Co-expression of multiple receptors including PD-1, LAG3, TIM-3, TIGIT, and CD39 [6].

- Dysregulated Metabolism and Epigenetics: Altered metabolic pathways and a distinct, stable epigenetic landscape that locks cells in the exhausted state.

- Subset Heterogeneity: The exhausted pool is not uniform. It contains progenitor exhausted (Tpex) cells that express TCF-1 and retain self-renewal capacity, and terminally exhausted (Tex-term) cells with profound dysfunction and a high burden of inhibitory receptors [5] [4].

Transcriptional and 3D Genomic Regulation of Exhaustion

Recent research has uncovered complex molecular mechanisms underpinning exhaustion. scRNA-seq of tumor-infiltrating T cells reveals a state co-expressing exhaustion, activation, and proliferation markers [3]. Furthermore, studies show that extensive changes in the three-dimensional (3D) genome architecture are critical for exhausted T cell differentiation. The transcription factor IRF8 was identified as a key driver of this process, promoting the formation of specific chromosomal loops that regulate the expression of exhaustion-associated genes. IRF8 deficiency inhibits the differentiation and antitumor function of exhausted CD8+ T cells [4].

Methodologies for Defining CD8+ T Cell Subsets

Polychromatic Flow Cytometry

Multiparameter flow cytometry remains a cornerstone for identifying and isolating T cell subsets based on surface and intracellular protein expression.

- Panel Design: Comprehensive panels include markers for differentiation (CD45RA, CCR7), costimulation/inhibition (CD27, CD28, CD57, KLRG1, PD-1, TIM-3), and tissue residency (CD69, CD103) [2].

- Experimental Workflow: PBMCs or tissue-derived lymphocytes are stained with a conjugated antibody panel, acquired on a flow cytometer capable of detecting 10+ colors, and analyzed using clustering algorithms (e.g., t-SNE, UMAP) to visualize populations [2].

In Vitro Modeling of T Cell Exhaustion

Reproducible in vitro models are essential for studying T cell exhaustion. One established method involves the chronic stimulation of naive T cells with cognate antigen [8].

- Protocol: Human or mouse T cells are repeatedly stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads or peptide-pulsed antigen-presenting cells over several weeks.

- Validation: The model is validated by confirming hallmarks of exhaustion: expression of PD-1, CD39, etc.; impaired proliferation and cytokine production; reduced cytotoxic granule release; and metabolic alterations. The model's relevance is benchmarked against in vivo exhausted T cells from chronic infection or tumor models [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Experimental Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CD8+ T Cell Subset Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD3/CD28 Antibodies | Activation | Polyclonal T cell stimulation via TCR and costimulatory pathways | In vitro T cell activation and expansion; modeling exhaustion [8] |

| 10x Genomics Chromium | scRNA-seq | Single-cell barcoding and library preparation for transcriptome analysis | Defining core transcriptional states in human tissue T cells [3] |

| Fluorochrome-conjugated Antibodies | Flow Cytometry | Multiplexed detection of cell surface and intracellular proteins | Polychromatic phenotyping of N, EM, TEMRA, and exhausted subsets [2] |

| PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade | Immunotherapy | Checkpoint inhibition to reinvigorate exhausted T cells | Functional assay to test Tpex cell potential and therapeutic response [7] |

| Humanized Mouse Models | In vivo Modeling | Study human T cell responses in an in vivo context | Evaluating tumor infiltration and function of human CD137+ CD8+ T cells [6] |

CD8+ T Cell Trafficking and Tissue Localization

The localization of CD8+ T cells to specific tissues is a dynamic process regulated by receptor-ligand interactions, which change as cells transition from naive to effector and memory states [1]. This trafficking is critical for effective immune surveillance and pathogen control.

Table 3: Key Receptor-Ligand Pairs in CD8+ T Cell Trafficking

| Receptor Type | Receptor | Ligand(s) | Role in CD8+ T Cell Trafficking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selectin | L-selectin (CD62L) | PNAd (MECA-79+) | Homing of naive cells to lymph nodes via HEVs [1] |

| P-selectin (CD62P) | PSGL-1 | Rolling/tethering to inflamed endothelium [1] | |

| Chemokine Receptor | CCR7 | CCL19, CCL21 | Guides naive and TCM cells to lymphoid organs [1] |

| CXCR3 | CXCL9, CXCL10 | Recruits effector and memory cells to sites of inflammation [1] | |

| Integrin | LFA-1 (αLβ2) | ICAM-1 | Mediates firm adhesion to endothelium prior to extravasation [1] |

| α4β7 | MAdCAM-1 | Gut-homing receptor [1] | |

| VLA-4 (α4β1) | VCAM-1 | Adhesion to inflamed endothelium [1] |

Implications for Therapeutics and Drug Development

A precise understanding of CD8+ T cell subsets directly informs immunotherapeutic development.

- Checkpoint Immunotherapy: The responsiveness of progenitor exhausted (Tpex) cells to PD-1 blockade makes them a key predictive biomarker and target for cancer immunotherapy [5] [4].

- Adoptive Cell Transfer (ACT): Identifying tumor-reactive T cell populations, such as the CD137+ CD8+ T cells with an activated and exhausted-like phenotype, allows for the selection of superior products for ACT [6].

- Vaccine Development: Strategies that promote the generation of long-lived memory subsets, particularly tissue-resident memory (TRM) cells, are being pursued to create durable protective immunity [1] [3].

The definition of core CD8+ T cell subsets has evolved from a simple linear model to a complex framework of interconnected states, intricately shaped by antigen exposure, tissue microenvironment, and transcriptional and epigenetic networks. The integration of high-dimensional technologies like scRNA-seq has been instrumental in creating a refined reference map of these populations in health, providing a crucial baseline from which to dissect dysfunction in disease. This detailed understanding of subset-specific markers, functions, and regulatory mechanisms is paramount for designing next-generation vaccines and immunotherapies aimed at harnessing the potent power of CD8+ T cells against cancer, chronic infection, and autoimmune pathology.

Immunosenescence, the progressive remodeling of the immune system with age, represents a critical determinant of healthspan and disease susceptibility in the aging global population [9]. The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized the resolution at which we can interrogate these age-related changes, moving beyond bulk tissue analysis to reveal cellular and molecular diversity within the immune compartment [9]. This technical guide synthesizes recent landmark studies utilizing single-cell technologies to dissect specific alterations within the human CD8+ T cell landscape, focusing on two pivotal, interconnected phenomena: the counterintuitive loss of a unique NKG2C+GZMB- CD8+ memory T cell subset and the systematic accumulation of type 2-polarized memory T cells. These findings are framed within a broader thesis that single-cell T cell atlas research is essential for decoding the molecular logic of immune aging, with significant implications for vaccine development, cancer immunotherapy, and the treatment of age-related inflammatory diseases.

Quantitative Atlas of Age-Associated T Cell Remodeling

Large-scale single-cell profiling of healthy human blood across adult lifespans has provided an unprecedented quantitative resource for understanding immune aging. A study profiling ~2 million cells from 166 individuals aged 25-85 years identified 55 immune subpopulations and found that 12 of these changed significantly with age [10] [11]. These changes represent a fundamental reprogramming of the peripheral T cell compartment.

Table 1: Key Age-Associated Changes in Human T Cell Compartment

| Immune Cell Subset | Change with Age | Functional Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NKG2C+GZMB- CD8+ Memory T Cells | Decrease | Counterintuitive loss of a distinct memory subset; potential role in viral surveillance | [10] |

| GZMK+ CD8+ T Cells | Accumulation | Pro-inflammatory, exhausted-like phenotype (PD-1+, LAG3+); accounts for ~40% of CD8+ TEM/TCM in older adults | [12] |

| Type 2 Memory CD4+ T Cells (Th2) | Accumulation | Systematic shift towards type 2 immunity; linked to dysregulated B cell responses | [13] [10] |

| CCR4+ CD8+ Tcm | Accumulation | CD8+ T cell subset exhibiting a type 2 cytokine profile (e.g., IL-4) | [10] |

| Cytotoxic CD4+ T Cells | Accumulation | Express cytotoxic molecules (Granzyme B, Perforin); increased in supercentenarians | [12] |

| HLA-DR+ CD4+ T Cells | Accumulation | Activated memory phenotype | [10] |

| Naive CD8+ T Cells | Decrease | Reduced thymic output and frequency | [13] [12] |

| Naive CD4+ T Cells | Stable Frequency | Despite non-linear transcriptional reprogramming | [13] |

This remodeling is not merely compositional. A 2025 longitudinal study profiling over 300 healthy adults with single-cell RNA sequencing, proteomics, and flow cytometry revealed that T cells exhibit the most profound transcriptional alterations prior to advanced ageing, with naive T cells showing the highest number of age-related differentially expressed genes (DEGs), followed by central memory (TCM) and effector memory (TEM) cells [13]. This reprogramming leads to a functional T helper 2 (TH2) cell bias in memory T cells that is linked to dysregulated B cell responses against antigens in influenza vaccines [13].

Experimental Protocols for scRNA-seq Based Immune Aging Research

The insights into NKG2C+ CD8+ T cell loss and type 2 memory accumulation were enabled by sophisticated single-cell methodologies. The following protocols detail the key experimental workflows used in the cited studies.

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Single-Cell Profiling of Human PBMCs

This protocol outlines the multi-omic approach used to generate the single-cell atlas of healthy human blood [10] [11].

- Sample Collection and Processing: Collect peripheral blood from donors across the target age range (e.g., 25-85 years). Isolate Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) via density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque PLUS.

- Single-Cell Library Preparation: Process single-cell suspensions using the 10x Genomics Chromium platform, typically with a 5' v2 kit that enables simultaneous capture of RNA, T Cell Receptor (TCR), and B Cell Receptor (BCR) sequences. Include feature barcoding for surface protein detection (CITE-seq).

- Sequencing: Sequence the generated libraries on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq 6000) to a sufficient depth for transcriptome, TCR, and BCR recovery.

- Data Preprocessing and Quality Control: Process raw sequencing data through Cell Ranger or similar pipelines. Perform rigorous quality control: filter out low-quality cells (e.g., those with <200 genes or >5% mitochondrial gene content) and remove doublets using tools like DoubletFinder.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Cell Type Annotation: Normalize and scale data using Seurat. Cluster cells with Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). Annotate cell clusters using reference-based tools (e.g., Azimuth) and canonical marker genes.

- Differential Expression & Abundance: Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between age groups within specific cell subsets using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Analyze changes in cell population frequency with age.

- TCR Analysis: Reconstruct TCR clonotypes from sequencing data to track clonal expansion and repertoire diversity.

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of Age-Associated T Cell Subsets

This protocol, derived from a study on Ankylosing Spondylitis, describes how to validate the function of identified subsets like NKG2C+ CD8+ T cells [14].

Immune Phenotyping by High-Dimensional Flow Cytometry:

- Stain fresh peripheral blood or PBMCs with a pre-titrated panel of ~51 surface antibodies.

- Include antibodies against key markers: CD3, CD8, CD45, NKG2C, CCR4, CD45RA, CD197 (CCR7), and CD107a. Incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature, lyse red blood cells, wash, and acquire data on a high-parameter cytometer (e.g., CytoFLEX LX).

- Analyze data to confirm the frequency and phenotype of age-altered subsets.

Degranulation/Cytotoxicity Assay:

- Isolate PBMCs and cryopreserve. For the assay, thaw and rest cells.

- Stimulate cells with an activation cocktail (e.g., PMA/ionomycin) or specific antigen in the presence of APC-conjugated anti-CD107a antibody and a protein transport inhibitor for 6 hours.

- After stimulation, perform surface staining, followed by fixation/permeabilization and intracellular cytokine staining (e.g., for IFN-γ, IL-4).

- Acquire data on a flow cytometer and analyze CD107a exposure and cytokine production in specific T cell subsets.

Phosphoflow to Probe Signaling Pathways:

- Coculture NKG2C+ CD8+ T cells with target cells (e.g., K562 cells transduced with HLA-B27 or control) for 6 hours.

- At the end of the culture, fix cells immediately with paraformaldehyde-containing buffer.

- Permeabilize cells using ice-cold methanol and stain with a phospho-specific antibody (e.g., Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-phospho-Akt) alongside surface markers.

- Analyze phospho-protein signaling by flow cytometry to validate pathway activation (e.g., PI3K-Akt).

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The age-related shift in T cell function is underpinned by distinct molecular pathways. The cytotoxicity of aging-associated NKG2C+ CD8+ T cells is regulated by specific receptor signaling and metabolic reprogramming.

The NKG2C+ CD8+ T cell subset, which paradoxically decreases with age, recognizes the non-classical MHC molecule HLA-E [14]. In specific pathological contexts like Ankylosing Spondylitis, HLA-B27 stimulation has been shown to significantly enhance the cytotoxicity of this subset via activation of the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, an effect reversible by NKG2C blockade [14]. This pathway activation leads to increased degranulation and cytotoxic potential.

Concurrently, transcriptomic analyses reveal systematic metabolic reprogramming in aged T cells. Studies note enriched pathways related to the TCA cycle in old naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which could associate with increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production from dysfunctional mitochondria [12]. This metabolic shift is thought to support the pro-inflammatory, exhausted-like phenotype of accumulating GZMK+ CD8+ T cells and the concerted age-associated increase in type 2 memory T cells across both CD4+ and CD8+ lineages (e.g., Th2 CD4+ Tmem and CCR4+ CD8+ Tcm) [10] [12].

Successfully profiling age-associated immune remodeling requires a carefully selected set of reagents and tools. The following table compiles essential solutions derived from the methodologies cited in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Immune Aging Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Single-cell partitioning for RNA/TCR/BCR-seq | Simultaneous transcriptome and receptor sequencing of PBMCs [11] |

| Feature Barcoding Antibodies | Surface protein detection via CITE-seq | High-resolution immunophenotyping alongside transcriptomic data [10] |

| Anti-NKG2C Antibody | Phenotyping and functional blockade | Identifying the declining CD8+ subset; validating functional dependence [14] |

| Anti-CCR4 Antibody | Identification of type 2 T cells | Flow cytometric quantification of accumulating Th2-like cells [10] |

| Anti-CD107a (APC) | Degranulation and cytotoxicity assay | Measuring cytotoxic potential of T cell subsets upon activation [14] |

| Anti-pAkt (Alexa Fluor 647) | Phosphoflow signaling analysis | Quantifying PI3K-Akt pathway activation in specific T cells [14] |

| Seurat / Azimuth | Bioinformatic analysis and cell annotation | scRNA-seq data normalization, clustering, and reference-based labeling [11] [9] |

| Human Immune Health Atlas | Reference dataset for cell subset labeling | Defining 71 immune cell subsets in PBMC scRNA-seq data [13] |

Single-cell atlas research has unequivocally established that the age-associated loss of NKG2C+GZMB- CD8+ T cells and the accumulation of type 2 memory T cells are defining features of immune aging. These changes, reflecting a broader non-linear transcriptional reprogramming of the T cell compartment, contribute to a functional immune bias with direct consequences for vaccine responses and disease susceptibility [13] [10]. The emerging toolkit—combining high-parameter single-cell omics, functional assays, and bioinformatic clocks like sc-ImmuAging [15]—provides an unprecedented opportunity to decode the heterogeneity of immune aging. Future research must focus on integrating these multimodal data to move from correlation to causation, ultimately enabling the development of targeted interventions to modulate these specific T cell pathways and promote healthier immune function in the aging population.

The precise characterization of CD8+ T cell states in healthy human tissues represents a foundational challenge in immunology and is critical for accurately identifying pathogenic deviations in disease. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revealed an unprecedented degree of T cell heterogeneity, yet consistent definition of cell states across studies remains a major challenge due to the lack of standardized reference baselines [16]. CD8+ T cells, as crucial mediators of adaptive immunity, demonstrate remarkable functional plasticity, with their states shaped by anatomical location, antigen exposure, and metabolic programming. Establishing a reference framework of CD8+ T cell states in health is particularly urgent given the correlation between specific intratumoral T cell states and response to immunotherapies [17]. Such baselines enable researchers to distinguish between physiological T cell diversity and disease-associated alterations, thereby facilitating the identification of novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers for immune-mediated diseases.

Recent technological advances now permit large-scale profiling of human T cells across multiple tissues, moving beyond the traditional reliance on peripheral blood samples to encompass lymphoid and mucosal sites where the majority of T cells reside [18]. This review synthesizes findings from these pioneering efforts to establish a comprehensive baseline of healthy human CD8+ T cell states, detailing the transcriptional signatures, functional properties, and tissue-specific distributions that define this critical immune population. Furthermore, we provide technical guidance for implementing these reference frameworks in research settings, ensuring consistent annotation and interpretation of CD8+ T cell states across studies.

Establishing Transcriptional Baselines: Core CD8+ T Cell States in Healthy Tissues

Reference CD8+ T Cell States from Multi-Tissue Atlas

Comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis of over 50,000 resting and activated T cells from lung, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and blood of healthy organ donors has established a high-dimensional reference map of human T cell activation in health [18]. This foundational work identified four principal CD8+ T cell states conserved across tissue sites:

- TEM/TRM-like cells expressing CCL5, cytotoxicity-associated genes (GZMB, GZMK), and tissue residency markers (CXCR6, ITGA1)

- Activated TRM/TEM cells characterized by expression of IFNG, CCL4, and CCL3

- Terminally differentiated effector cells (TEMRA) marked by high expression of cytotoxic mediators PRF1 and NKG7

- Naïve-like cells expressing CCR7, SELL, TCF7, and IL7R [18]

The distribution of these states varies significantly by tissue compartment. Tissue-resident memory (TRM) cells are predominantly localized in mucosal sites such as the lung, while TEMRA cells are enriched in bone marrow. Naïve and central memory populations are more abundant in lymphoid tissues and blood [18].

Age-Associated Alterations in Circulating CD8+ T Cell Populations

Large-scale profiling of approximately 2 million peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 166 healthy individuals aged 25-85 years has revealed specific age-related shifts in CD8+ T cell populations [19]. This analysis identified 55 subpopulations of blood immune cells, with twelve subpopulations demonstrating significant changes with age:

- GZMK+ CD8+ T cells accumulate with age

- A unique NKG2C+ GZMB− XCL1+ memory CD8+ T cell subset decreases with age

- CCR4+ CD8+ Tcm (T central memory) cells show concerted age-associated increase alongside Th2 CD4+ T memory cells, suggesting a systematic functional shift toward type 2 immunity with aging [19]

Table 1: Core CD8+ T Cell States in Healthy Human Tissues

| Cell State | Key Marker Genes | Primary Tissue Localization | Functional Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve-like | CCR7, SELL, TCF7, IL7R | Blood, Lymph Nodes, Bone Marrow | Self-renewal capacity, differentiation potential |

| TEM/TRM-like | GZMB, GZMK, CXCR6, ITGA1, CCL5 | Lung, Mucosal Sites | Cytotoxic potential, tissue retention |

| Activated TRM/TEM | IFNG, CCL4, CCL3 | All Tissues | Pro-inflammatory cytokine production |

| TEMRA | PRF1, NKG7, FCGR3A | Bone Marrow, Blood | Strong cytotoxic activity, terminal differentiation |

| NKG2C+ GZMB− Memory | NKG2C, XCL1 | Blood | Unique memory subset, decreased with aging |

| GZMK+ CD8+ T cells | GZMK | Blood | Accumulates with age |

| CCR4+ CD8+ Tcm | CCR4 | Blood | Type 2/IL-4 expression, increases with age |

Methodological Framework for CD8+ T Cell State Identification

The experimental workflow for establishing these CD8+ T cell baselines typically involves several standardized steps [18]:

Sample Acquisition: Tissues are obtained from deceased organ donors meeting health criteria for transplantation, while blood is collected from healthy adult volunteers.

Cell Processing and Stimulation: CD3+ T cells are isolated from tissues and blood, then cultured either in media alone ("resting") or with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibody stimulation ("activated") to capture diverse activation states.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Single cells are encapsulated using the 10x Genomics Chromium system, followed by library construction and sequencing.

Computational Analysis: Unsupervised community detection algorithms cluster cells based on highly variable genes, with subsequent projection into two-dimensional space using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). Differential gene expression analysis then resolves T cell subsets and functional states.

This standardized approach enables consistent identification of CD8+ T cell states across donors and tissue sites, forming a reproducible framework for baseline establishment.

Analytical Frameworks for CD8+ T Cell State Annotation

Automated Annotation Tools and Reference-Based Projection

The field of scRNA-seq data analysis faces significant challenges in achieving consistent cell phenotype annotation, particularly for heterogeneous populations like T cells with their diverse functional states and highly variable T-cell receptors (TCRs) [20]. Several computational approaches have been developed to address this challenge:

Supervised machine learning classification methods include:

- SingleR enables prediction of cell-type labels for novel datasets based on models trained on prior annotated datasets [20]

- Garnett and CellTypist provide additional frameworks for supervised classification of cell states [20]

Semi-supervised approaches include:

- SCINA annotates cells based on a consensus list of known markers [20]

- scGate employs a hierarchical gating strategy similar to flow cytometry, classifying markers in a structure of pure and impure cells [20]

Reference atlas projection methods represent a particularly powerful approach for placing new data into established frameworks:

- ProjecTILs specializes in projecting new scRNA-seq data into reference T cell atlases without altering the reference space, while also characterizing previously unknown cell states that "deviate" from reference subtypes [16] [20]

- The algorithm applies the PCA rotation matrix of the reference map to the query set, then uses the same UMAP transformation to project query cells into the original UMAP embedding of the reference [16]

- Following projection, a nearest-neighbor classifier predicts the subtype of each query cell by majority vote of its annotated nearest neighbors in the reference map [16]

Integrated Annotation Strategy

For optimal results, a two-step annotation process is strongly recommended [20]:

- Primary annotations of gene expression clusters by automated algorithms

- Expert-based manual interrogation of cell populations to verify automated annotations

This combined approach leverages the scalability of computational methods while maintaining the biological validity ensured by expert knowledge, resulting in the most accurate definitions of CD8+ T cell subsets.

Table 2: Computational Tools for CD8+ T Cell State Annotation

| Tool | Approach | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProjecTILs | Reference projection | Projects new data into reference atlases without altering reference structure; identifies novel states | Preserves reference space integrity; enables cross-study comparison | Requires well-annotated reference atlas |

| SingleR | Supervised classification | Predicts cell-type labels based on pre-trained models | Robust to missing marker genes | Requires gene expression overlap with reference |

| scGate | Semi-supervised | Hierarchical gating strategy similar to flow cytometry | User-defined marker lists; interpretable method | Dependent on marker gene quality |

| SCINA | Semi-supervised | Annotation based on consensus marker lists | Utilizes known biological signatures | Limited to predefined cell populations |

| Seurat Clustering | Unsupervised | k-nearest neighbors clustering | Identifies novel populations without prior knowledge | Requires expert annotation after clustering |

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CD8+ T Cell scRNA-seq Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium System | Single-cell encapsulation and barcoding | High-throughput scRNA-seq library preparation | Enables capture of thousands of cells simultaneously |

| Anti-CD3/CD28 Activation Beads | T cell stimulation | Mimics antigen presentation and co-stimulation | Standardized activation for functional state assessment |

| Cell Hashing Antibodies | Sample multiplexing | Allows pooling of multiple samples in one run | Reduces batch effects and costs |

| Feature Barcoding Kits | Surface protein detection | Combined transcriptome and proteome analysis | Correlates protein expression with transcriptional states |

| TCR Amplification Kits | T cell receptor sequencing | Paired TCR sequence with gene expression | Links clonality to functional state |

| Viability Stains (e.g., LIVE/DEAD) | Dead cell exclusion | Improves data quality by removing dead cells | Critical for tissue samples with higher cell death |

| CellSorting Reagents (e.g., FACS Antibodies) | Target population isolation | Enrichment of CD8+ T cells prior to sequencing | Reduces sequencing costs and complexity |

| Reference Atlas Datasets (e.g., HCA) | Analytical framework | Projection and annotation of new datasets | Provides healthy baseline for comparison |

Metabolic and Functional Programming of CD8+ T Cell States

Metabolic Regulation of CD8+ T Cell Differentiation

CD8+ T cell states are intrinsically linked to their metabolic programming, with distinct metabolic pathways supporting different functional states [21] [22]. Naïve T cells primarily utilize oxidative phosphorylation to meet their energy demands, while upon activation, CD8+ T cells undergo metabolic rewiring to support their effector functions, dramatically increasing glycolytic flux and engaging biosynthetic pathways for clonal expansion [21].

Key metabolic features of CD8+ T cell states include:

- Asparagine metabolism plays a critical role in CD8+ T cell differentiation, with ASNS expression dynamics influencing T cell fate decisions [21]

- Glycolytic capacity is rapidly engaged upon T cell receptor activation, supporting effector differentiation [21]

- Neonatal CD8+ T cells exhibit unique metabolic programming, with heightened glycolytic engagement and accelerated effector differentiation compared to adult cells [23]

Functional Signatures of CD8+ T Cell Activation

Single-cell transcriptomics of activated T cells from multiple healthy tissues reveals conserved lineage-specific activation states [18]. For CD8+ T cells, this includes:

- Distinct effector states characterized by production of cytotoxic molecules (granzymes, perforin) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF)

- Tissue-specific functional adaptations with CD8+ T cells in mucosal sites exhibiting tissue-residency programs

- Heterogeneous activation responses even within defined CD8+ T cell subsets, reflecting the functional plasticity of this population

The establishment of comprehensive baselines for CD8+ T cell states in healthy individuals through large-scale single-cell profiling represents a transformative advancement in immunology. These reference maps enable researchers to distinguish physiological T cell diversity from disease-associated alterations, providing essential context for interpreting T cell states in cancer, autoimmunity, and infectious diseases. The integration of transcriptional data with metabolic, functional, and clonal information offers a multidimensional perspective on CD8+ T cell heterogeneity that more accurately reflects the complexity of this critical immune population.

Future efforts in this field will need to address several important challenges, including the standardization of annotation frameworks across laboratories, the integration of multi-omics data at single-cell resolution, and the expansion of tissue sampling to encompass a wider range of anatomical sites. Additionally, longitudinal studies tracking CD8+ T cell states over time and in response to immune challenges will provide dynamic insights beyond the static snapshots currently available. As these reference atlases continue to expand and refine, they will undoubtedly accelerate the development of targeted immunotherapies and precision medicine approaches that modulate specific CD8+ T cell states for therapeutic benefit.

CD8+ T cells are fundamental mediators of adaptive immunity, capable of directly eliminating pathogen-infected and cancerous cells. In the context of persistent antigen exposure, as occurs in chronic infections and cancer, these cells progressively differentiate into a hypofunctional state known as T cell exhaustion [24]. This dysfunctional state represents a significant barrier to effective immunity and poses a substantial challenge for immunotherapies. The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our understanding of this process, revealing that exhaustion is not a uniform terminal state but rather a spectrum of differentiation with distinct cellular subsets possessing unique transcriptional, epigenetic, and functional properties [25] [26]. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to characterize the heterogeneous subsets within the exhaustion spectrum, their regulatory mechanisms, and implications for therapeutic intervention.

Exhausted T (Tex) cells are characterized by progressive loss of effector functions, including reduced production of cytokines such as IL-2, TNF, and IFNγ, diminished cytotoxic capacity, and increased expression of multiple inhibitory receptors (IRs) including PD-1, TIM-3, TIGIT, LAG-3, and CTLA-4 [27] [24]. Unlike functional memory or effector T cells, Tex cells exhibit a distinct transcriptional landscape governed by factors such as TOX and NFAT, which reinforce the exhausted phenotype while suppressing more functional T cell states [27] [26]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) further enforces this dysfunction through metabolic stress, including hypoxia and accumulation of immunosuppressive metabolites like lactic acid [26].

Characterizing the Exhaustion Spectrum

Major Subsets Along the Exhaustion Trajectory

Single-cell transcriptomic analyses across numerous human cancers and chronic infection models have consistently identified a hierarchical differentiation system within the exhaustion spectrum, primarily composed of two major subsets: progenitor exhausted (Tpex) and terminally exhausted (Tex) T cells [25] [26].

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Exhausted T Cell Subsets

| Feature | Progenitor Exhausted (Tpex) | Terminally Exhausted (Tex) |

|---|---|---|

| Key Markers | PD-1int, TCF-1+, SLAMF6hi, TOXint | PD-1hi, TIM-3+, SLAMF6lo, TOXhi |

| Self-Renewal | High | Limited |

| Effector Function | Retained cytokine production | Severely impaired polyfunctionality |

| Metabolic Features | [Information missing] | MCT11hi, enhanced lactate uptake |

| Therapeutic Response | Responsive to PD-1 blockade | Poor response to checkpoint inhibition |

| Developmental Fate | Self-renew and differentiate into Tex | Developmental dead-end |

The exhaustion trajectory begins with an early bifurcation event where activated CD8+ T cells diverge toward either functional memory or exhaustion lineages, a decision point marked by TCF-1 expression and occurring within the first few days of chronic antigen exposure [25]. From this branch point, Tpex cells demonstrate sustained expression of TCF-1 (encoded by TCF7), which maintains their proliferative potential and capacity for self-renewal, while Tex cells downregulate TCF-1 and upregulate a suite of inhibitory receptors along with the transcription factor TOX, which stabilizes the exhausted phenotype [26].

Heterogeneity Within Exhausted T Cell Populations

Beyond the fundamental Tpex/Tex dichotomy, finer-resolution scRNA-seq analyses have revealed additional specialized subsets within the exhaustion spectrum, particularly in human cancers:

Tissue-Resident Memory-like (TRM) Exhausted T Cells: In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a subset of exhausted T cells with TRM-like features (CD69+ CD103+) was identified through scRNA-seq. Developmental trajectory analysis suggested that exhausted CD8+ T cells might develop via TRM cells in the AML tumor microenvironment, with these cells exhibiting significantly higher expression of exhaustion molecules [27].

EOMEShi T-bethi Terminal Exhaustion Subsets: Multi-omic integration of ATAC-seq and RNA-seq data has identified further stratification within the Tex compartment, including discrete populations with varying expression ratios of T-bet and EOMES, which correlate with differential cytotoxic potential and proliferative capacity [25].

Metabolically Specialized Tex Subsets: Recent work has identified a specialized Tex subset that highly expresses the lactate transporter MCT11 (SLC16A11), enabling increased uptake and metabolism of lactic acid in the TME. This metabolic adaptation further reinforces the dysfunctional state, as genetic or antibody-mediated disruption of MCT11 improves Tex cell effector function and reduces tumor growth [26].

Table 2: Exhaustion Markers Across Disease Contexts

| Marker Category | Specific Markers | Associated Dysfunctional State |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitory Receptors | PD-1, CTLA-4, TIM-3, TIGIT, LAG-3, BTLA | Exhausted T cells [27] [24] [28] |

| Transcription Factors | TOX, NFAT, BATF, Blimp-1, T-betlo, EOMEShi | Terminal exhaustion [27] [24] [26] |

| Metabolic Transporters | MCT11 (SLC16A11) | Lactate-uptake specialized Tex [26] |

| Functional Markers | CD39, CD69, CD103 | Tissue-resident exhaustion [27] [28] |

| NK Cell Exhaustion | KLRC1, TIGIT, PD-1, TIM-3, reduced GZMB | NK cell dysfunction [27] [29] |

Molecular Drivers of Exhaustion Heterogeneity

Transcriptional and Epigenetic Regulation

The exhaustion spectrum is underpinned by distinct transcriptional and epigenetic programs that diverge early from other T cell fate trajectories. Unified analysis of over 300 ATAC-seq and RNA-seq datasets revealed that functional and dysfunctional T cells diverge at an early branch point marked by TCF-1 expression, with Tex cells subsequently following a differentiation path governed by progressive epigenetic changes that limit developmental plasticity [25].

The transcription factor TOX is a central regulator of exhaustion, induced by persistent TCR stimulation and necessary for the development of Tex cells. TOX expression promotes the exhausted phenotype by enacting transcriptional changes that reinforce dysfunction while suppressing memory and effector programs. Complementary to TOX, the NFAT signaling axis drives exhaustion-associated gene expression programs, often in cooperation with other factors such as BATF [24] [26].

Epigenetic analysis demonstrates that Tex cells acquire a distinct chromatin accessibility landscape characterized by stable changes at exhaustion-specific loci. These epigenetic modifications lock in the exhausted phenotype even in the absence of continuous antigen exposure, explaining the persistence of dysfunction in adoptive cell transfers and the limited durability of responses to checkpoint inhibition in many patients [25].

Metabolic Regulation in the Tumor Microenvironment

The TME imposes significant metabolic constraints that shape and reinforce the exhaustion spectrum. Terminally exhausted T cells exist in a state of metabolic dysfunction characterized by disrupted mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation [26]. Recent research has identified MCT11 (SLC16A11) as a key metabolic transporter specifically upregulated in Tex cells, enabling increased uptake of lactic acid from the TME [26].

Figure 1: Metabolic Regulation of T Cell Exhaustion via MCT11

This metabolic specialization creates a feed-forward loop wherein Tex cells become increasingly dependent on lactic acid metabolism, further entrenching their dysfunctional state. Genetic deletion of MCT11 in T cells reduces lactic acid uptake and improves effector function, demonstrating the functional significance of this metabolic adaptation [26]. Hypoxia in the TME, mediated through Hif1α, further drives sustained MCT11 expression, creating a synergistic relationship between metabolic and transcriptional drivers of exhaustion [26].

Research Methods and Experimental Protocols

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for Characterizing Exhaustion

scRNA-seq has emerged as the cornerstone technology for delineating the exhaustion spectrum, enabling unprecedented resolution of heterogeneous subsets and their transcriptional programs.

Table 3: Key Experimental Protocols for Exhaustion Research

| Method | Key Applications | Critical Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing | Identification of exhausted subsets, trajectory inference, transcriptional profiling | 1. Single-cell suspension preparation2. Viability assessment (>80% recommended)3. Cell partitioning and barcoding (10x Genomics)4. Library preparation and sequencing5. Bioinformatics analysis (Seurat, Monocle) |

| T Cell Receptor Sequencing | Clonotype tracking, lineage relationships | Paired TCR capture with gene expression |

| ATAC-seq | Epigenetic landscape analysis, chromatin accessibility | Transposase treatment of intact nuclei, sequencing |

| Flow Cytometry Validation | Protein-level marker validation, functional assessment | Multi-parameter staining (PD-1, TIM-3, TIGIT, TCF-1, TOX) |

| Metabolic Assays | Characterization of metabolic dependencies | [14C]-lactate uptake, OCR, ECAR measurements |

A typical scRNA-seq workflow begins with the preparation of a high-quality single-cell suspension from tumor tissue, peripheral blood, or model system. Critical quality control steps include viability assessment (typically >80% recommended), removal of doublets using tools like DoubletFinder, and filtration of low-quality cells (e.g., those with <200 UMIs or >20% mitochondrial gene expression) [27]. Following library preparation and sequencing, bioinformatic analysis using tools such as Seurat and Monocle enables identification of distinct cellular subsets, trajectory inference, and differential gene expression analysis [27].

For exhaustion studies specifically, developmental trajectory analysis using tools like Monocle can reconstruct the differentiation path from progenitor to terminally exhausted states, identifying significantly changed genes (q-value < 0.01) along this continuum [27]. Integration with paired TCR sequencing further enables tracking of clonal expansion and lineage relationships across the exhaustion spectrum [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for T Cell Exhaustion Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Isolation | CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kits | Purification of T cell populations for sequencing and functional assays |

| scRNA-seq Platforms | 10x Genomics Chromium, Seq-Well | Single-cell transcriptome profiling of heterogeneous populations |

| Inhibitory Receptor Antibodies | α-PD-1, α-TIGIT, α-TIM-3, α-CTLA-4 | Immune checkpoint blockade in functional assays and therapeutic studies |

| Transcription Factor Antibodies | α-TOX, α-TCF-1, α-T-bet, α-EOMES | Protein-level validation of transcriptional regulators |

| Metabolic Tools | [14C]-lactate, MCT11-blocking antibodies | Assessment of metabolic dependencies and therapeutic targeting |

| Animal Models | Nf1-OPG mice, B16 melanoma, MC38 | In vivo study of exhaustion in tumor microenvironments |

Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

Diagnostic and Prognostic Significance

The composition of the T cell exhaustion spectrum holds significant diagnostic and prognostic value across disease contexts. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the presence of exhausted T cell populations with elevated expression of checkpoint molecules correlates with disease progression and impaired anti-leukemic immunity [27]. Similarly, in low-grade gliomas (LGGs), the abundance of PD-1+ TIGIT+ CD8+ exhausted T cells exceeds that in high-grade gliomas and correlates with tumor growth patterns [28].

Notably, different subsets within the exhaustion spectrum carry distinct prognostic implications. Progenitor exhausted T cells, with their retained proliferative capacity and responsiveness to checkpoint inhibition, are associated with improved outcomes following immunotherapy [25]. In contrast, the accumulation of terminally exhausted subsets often predicts limited therapeutic response and more aggressive disease courses [26].

Therapeutic Targeting of Exhaustion Subsets

Current immunotherapeutic approaches predominantly target the exhaustion spectrum through immune checkpoint blockade (e.g., α-PD-1, α-PD-L1, α-CTLA-4), which primarily reinvigorates the progenitor exhausted population [25]. However, the limited success of these approaches in many solid tumors has highlighted the need for strategies that address the full complexity of the exhaustion spectrum.

Emerging therapeutic approaches include:

Metabolic Targeting: Antibody-mediated blockade of MCT11 reduces lactate uptake specifically in Tex cells, improving their effector function and reducing tumor growth in preclinical models, either as monotherapy or in combination with α-PD-1 [26].

Multi-checkpoint Inhibition: In low-grade glioma models, combined α-PD-1 and α-TIGIT therapy attenuates tumor proliferation through suppression of both Ccl4 and TGFβ-mediated mechanisms, demonstrating superior efficacy to single-agent approaches [28].

Precursor-directed Therapies: Strategies that preserve or expand the progenitor exhausted population, which maintains self-renewal capacity and responsiveness to checkpoint blockade, represent a promising approach for sustaining anti-tumor immunity [25].

Figure 2: Therapeutic Targeting Across the Exhaustion Spectrum

The characterization of CD8+ T cell exhaustion as a spectrum of distinct dysfunctional subsets represents a fundamental advancement in our understanding of adaptive immunity in chronic disease. Single-cell technologies have been instrumental in revealing the heterogeneity within this spectrum, from progenitor populations that retain self-renewal capacity to terminally exhausted subsets with distinct metabolic and epigenetic features. This refined understanding enables more precise diagnostic stratification and reveals new therapeutic opportunities that extend beyond broad checkpoint inhibition to include metabolic modulation and combination approaches targeting multiple nodes along the exhaustion trajectory. As these insights are translated into clinical practice, they hold significant promise for improving outcomes in cancer and chronic infection through immunotherapies that account for the full complexity of the T cell exhaustion spectrum.

Building and Interpreting T Cell Atlases: AI-Driven Integration and Reference-Based Projection

The remarkable phenotypic diversity of CD8+ T cells in inflammation and cancer has long presented a significant challenge in immunology research. While these cells play crucial roles in immune responses across various diseases, a comprehensive understanding of their clonal landscape and dynamics has remained elusive due to limitations in integrating large-scale single-cell datasets. The scAtlasVAE computational framework represents a transformative approach to this challenge, enabling the construction of an extensive human CD8+ T cell atlas through advanced deep learning methodologies. This atlas comprises an unprecedented 1,151,678 cells from 961 samples across 68 studies and 42 disease conditions, all with paired T cell receptor (TCR) information [5] [30] [31].

The fundamental innovation of scAtlasVAE lies in its ability to overcome the persistent obstacles in cross-study comparisons of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data. Traditional analyses are complicated by batch effects and inconsistencies in cell subtype annotation, which scAtlasVAE addresses through a specialized variational autoencoder (VAE) architecture [32]. By integrating both transcriptomic and TCR sequence data at an unprecedented scale, this framework not only maps cellular diversity but also establishes connections between distinct cell subtypes, illuminating their phenotypic and functional transitions in ways previously impossible with conventional analytical methods [5].

Table 1: Scale and Composition of the Integrated CD8+ T Cell Atlas

| Atlas Component | Quantity | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total Cells | 1,151,678 | Enables robust statistical power for rare cell population identification |

| Biological Samples | 961 | Captures extensive biological variability across conditions |

| Independent Studies | 68 | Integrates diverse experimental designs and protocols |

| Disease Conditions | 42 | Facilitates cross-condition comparative analyses |

| Paired TCR Profiles | 1,151,678 | Links transcriptomic states with clonal dynamics |

Core Architecture and Technical Innovations

scAtlasVAE Deep Learning Framework

The scAtlasVAE framework employs a sophisticated variational autoencoder (VAE) architecture specifically designed for single-cell genomics data integration. This model utilizes a batch-invariant encoder to identify biologically relevant and essential features within cells, effectively separating biological signals from technical artifacts. Complementing this, the batch-dependent decoder learns and mitigates batch-related information, enabling seamless integration of datasets across different studies and platforms [32]. This dual approach allows the model to preserve biologically meaningful variation while removing technically induced biases that have traditionally hampered large-scale meta-analyses in single-cell research.

The technical implementation of scAtlasVAE processes single-cell data through multiple transformation layers that simultaneously handle gene expression quantification, TCR sequence integration, and clonal expansion metrics. The model's latent space is structured to capture continuous biological processes such as T cell differentiation trajectories and activation states, rather than forcing cells into discrete, artificially bounded populations. This approach has proven particularly valuable for understanding CD8+ T cell biology, where cells exist along continuous differentiation spectra rather than in discrete functional boxes [5].

Integration of T Cell Receptor Information

A groundbreaking aspect of the scAtlasVAE framework is its sophisticated integration of paired TCR sequence data with transcriptomic profiles. By incorporating information on TCR clonal expansion and clonal sharing across samples and conditions, the model successfully establishes connections between distinct cell subtypes and illuminates their phenotypic and functional transitions [5]. This integration enables researchers to track how specific T cell clones expand, differentiate, and acquire specialized functional capabilities across different tissue environments and disease contexts.

The TCR analysis capabilities extend to identifying public TCR sequences - identical receptor sequences shared across multiple individuals - which often target epitopes from common viruses such as EBV, CMV, and influenza A [30]. This aspect of the framework has profound implications for understanding conserved immune responses and developing immunotherapies that leverage public TCR sequences with demonstrated antigen specificity and protective capacity.

Experimental Framework and Methodological Protocols

Data Collection and Preprocessing

The construction of the human CD8+ T cell atlas through scAtlasVAE followed a rigorous data collection and preprocessing protocol. The initial phase involved aggregating raw single-cell RNA sequencing data from 68 publicly available studies, ensuring comprehensive coverage of diverse disease conditions including cancer, autoimmune disorders, and infectious diseases [5] [30]. Each dataset underwent standardized quality control procedures including filtering of low-quality cells, gene expression normalization, and batch effect assessment prior to integration. The scale of this effort is reflected in the final atlas encompassing nearly 1.2 million cells, each with meticulously curated metadata annotation.

A critical aspect of the preprocessing workflow was the handling of paired TCR sequencing data, which required specialized alignment and annotation pipelines to extract productive TCRα and TCRβ sequences from each T cell. The framework incorporated TCR clonotype calling algorithms to identify cells belonging to the same original T cell clone based on shared TCR sequences, enabling subsequent analyses of clonal expansion and trajectory mapping [30]. This comprehensive approach to data harmonization established the foundation for robust cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses that would otherwise be compromised by technical variability.

Model Training and Validation

The training protocol for scAtlasVAE employed a semi-supervised learning approach that leveraged available cell type annotations while allowing the model to discover novel cell states. The VAE architecture was trained to minimize reconstruction loss while simultaneously maximizing batch invariance in the latent representation. Validation procedures included cross-validation across datasets to assess generalization performance and benchmarking against established integration methods such as Seurat and Harmony to quantify improvements in batch correction and biological preservation [5].

Model validation extended beyond technical metrics to include biological validation using TCR clonal tracking as an independent measure of integration quality. The fundamental premise that cells sharing the same TCR sequence (and therefore originating from the same parent cell) should occupy neighboring regions in the integrated latent space provided a powerful biological validation criterion. This approach confirmed that scAtlasVAE successfully preserved biological relationships while effectively removing technical artifacts, outperforming existing methods in maintaining clonal family coherence across integrated datasets [5] [30].

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols in Atlas Construction

| Protocol Step | Methodological Approach | Quality Control Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | Aggregation from 68 public studies | Standardized metadata annotation using controlled vocabularies |

| Cell QC | Filtering based on gene counts, UMIs, and mitochondrial percentage | Retention of cells with >500 genes and <20% mitochondrial reads |

| TCR Processing | TRACE2 and MIXCR pipelines for sequence assembly | Productive sequence rate >70% per dataset |

| Data Integration | scAtlasVAE with batch-invariant encoding | Batch effect removal score >0.8, biological conservation >0.9 |

| Cell Annotation | Hierarchical clustering with manual curation | Concordance >85% with independent expert annotation |

Core Computational Tools and Frameworks

The successful implementation of scAtlasVAE relies on a carefully curated ecosystem of computational tools and frameworks. The core model is built using Python-based deep learning libraries including TensorFlow or PyTorch for the VAE implementation, with specialized extensions for single-cell data handling. Preprocessing dependencies include Scanpy and Seurat for initial data quality control and normalization, ensuring compatibility with standard single-cell analysis workflows [30] [33]. For TCR sequence analysis, the framework incorporates TCRdist and related packages for clonotype definition and similarity quantification.

Beyond the core algorithm, the scAtlasVAE ecosystem includes specialized visualization tools designed to handle the complexity of large-scale integrated atlases. The Palo package provides spatially-aware color palette optimization specifically for single-cell and spatial genomic data, addressing the critical challenge of visualizing dozens of cell clusters with distinct yet related identities [34]. This tool identifies pairs of clusters that are spatially neighboring in visualization layouts and assigns visually distinct colors to these neighboring clusters, significantly enhancing interpretability of complex atlas visualizations.

The scAtlasVAE framework is complemented by comprehensive reference datasets that enable automatic annotation of query datasets. The primary human CD8+ T cell reference atlas incorporates 18 meticulously annotated cell subtypes defined through a combination of canonical marker expression, transcriptional signatures, and functional potential [5]. Each subtype is associated with detailed metadata including tissue distribution, disease associations, and differentiation trajectories, providing essential biological context for annotation results.

Additional specialized reference atlases expand the utility of the framework for specific research applications. The ProjecTILs human reference atlas of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating T cells provides detailed annotation of tumor-specific T cell states across seven cancer types, enabling precise characterization of tumor microenvironment composition [35]. Similarly, the population-level TCRαβ repertoire atlas integrates paired single-cell RNA/TCR sequencing data from over 2 million T cells across 70 studies, revealing intrinsic features of germline-encoded TCR-MHC restrictions and public TCR sequences shared across individuals [30].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for scAtlasVAE Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Access Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Algorithm | scAtlasVAE Python package | Data integration and batch correction | GitHub repository |

| Reference Atlas | Human CD8+ T cell atlas | Automatic cell annotation | huARdb database |

| TCR Analysis | TCR-DeepInsight | Identification of disease-associated TCRs | GitHub repository |

| Color Optimization | Palo R package | Spatially-aware visualization | CRAN/Bioconductor |

| Data Portal | huARdb v2 | Interactive clonotype-transcriptome analysis | huARdb website |

Key Applications and Biological Insights

Characterization of T Cell Exhaustion Heterogeneity

The application of scAtlasVAE to human CD8+ T cell biology has yielded transformative insights into the heterogeneity of T cell exhaustion, a critical dysfunctional state in chronic infections and cancer. The framework successfully characterized three distinct exhausted T cell (Tex) subtypes that exhibit divergent clonal relationships with tissue-resident memory T (Trm) cells or circulating T cells [5] [32]. These subtypes include GZMK+ exhausted T cells and ITGAE+ exhausted T cells, which are enriched in distinct cancer types and demonstrate unique differentiation trajectories. This refined classification moves beyond the traditional monolithic view of T cell exhaustion to reveal a spectrum of dysfunctional states with implications for immunotherapy response prediction.

The integration of TCR clonal information with transcriptomic states has been particularly revealing for understanding exhaustion dynamics. Analysis of clonal expansion patterns demonstrated that specific T cell clones can give rise to multiple exhausted subsets, suggesting a branching differentiation model rather than a linear progression. Furthermore, the discovery of clonal sharing patterns between exhausted subsets in cancer and inflammatory conditions points to shared mechanistic pathways underlying T cell dysfunction across disease contexts [5]. These insights provide a more nuanced framework for developing targeted interventions that reverse specific exhaustion subtypes while preserving beneficial T cell functions.

Insights into Inflammatory and Autoimmune Conditions

Beyond cancer biology, scAtlasVAE has enabled groundbreaking discoveries in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases by revealing diverse transcriptome and clonal sharing patterns in autoimmune conditions and immune-related adverse events (irAEs) [5]. The integrated atlas approach has identified shared T cell states across different inflammatory conditions, suggesting common mechanistic pathways that might be targeted with broad-spectrum immunomodulatory therapies. Conversely, condition-specific T cell signatures point to disease-specific mechanisms that could inform more precise diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

The application of TCR clonal analysis in autoimmune contexts has revealed unexpected relationships between apparently distinct cell populations. Clonal sharing between regulatory and effector T cell subsets in autoimmune inflammation suggests greater plasticity than previously appreciated, with potential implications for understanding treatment responses and disease fluctuations [5]. Similarly, the identification of public TCR sequences in autoimmune lesions points to possible antigen-specific triggers that might be targeted for more specific therapeutic interventions with fewer off-target effects than current broad immunosuppressive approaches.

Implementation Guide and Best Practices

Practical Workflow for Query Dataset Analysis

The implementation of scAtlasVAE for analyzing new query datasets follows a structured workflow that begins with proper experimental design and data generation. Researchers should prioritize single-cell RNA sequencing with paired TCR profiling to fully leverage the atlas's capabilities, using established protocols such as 10x Genomics 5' scRNA-seq with feature barcoding for TCR capture. The minimum recommended cell number for robust analysis is 5,000 CD8+ T cells, though smaller datasets can be analyzed with appropriate statistical considerations for rare cell population detection [5].

Once data generation is complete, the computational analysis proceeds through sequential stages:

- Data Preprocessing: Quality control, normalization, and feature selection using standard single-cell analysis tools

- Reference Mapping: Projection of query data into the scAtlasVAE latent space using the batch-invariant encoder

- Automatic Annotation: Cell type assignment based on similarity to reference atlas populations

- Clonal Analysis: TCR sequence processing and integration with transcriptional states

- Comparative Analysis: Assessment of population differences across experimental conditions

The framework provides quantitative confidence scores for automatic cell type annotations, enabling researchers to identify ambiguous assignments that might require manual validation or additional experimental characterization [5].

Interpretation Guidelines and Pitfall Avoidance

Effective interpretation of scAtlasVAE results requires careful consideration of several key principles. First, the continuous nature of the latent space means that cells exist along differentiation gradients rather than in discrete compartments, so population boundaries should be interpreted as useful abstractions rather than absolute biological distinctions. Second, the integration of TCR clonal information provides orthogonal validation of transcriptional relationships - cells sharing TCR sequences should generally occupy neighboring regions in visualizations, and deviations from this pattern warrant further investigation [5].

Common pitfalls in implementation include inadequate cell numbers for rare population detection, failure to account for technology-specific biases in cross-platform comparisons, and overinterpretation of automated annotations without biological validation. Researchers should employ multi-level validation strategies including: (1) examination of canonical marker expression in annotated populations, (2) functional assessment through gene set enrichment analysis, and (3) where possible, experimental validation of predicted cellular behaviors or differentiation potential [5] [30]. This comprehensive approach ensures that computational insights translate to biologically meaningful discoveries with potential therapeutic relevance.

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

The scAtlasVAE framework represents a paradigm shift in single-cell data analysis, moving from isolated dataset examination to integrated atlas-scale comprehension. The demonstrated applications across cancer, autoimmunity, and infectious diseases highlight the transformative potential of this approach for unifying our understanding of CD8+ T cell biology across traditional disease boundaries [5] [32]. The identification of conserved cell states and differentiation pathways across conditions suggests the existence of fundamental organizational principles governing T cell responses that transcend specific disease contexts.

Looking forward, several exciting directions promise to extend the impact of scAtlasVAE and similar integrative frameworks. The incorporation of additional data modalities including epigenomic, proteomic, and spatial information will create more comprehensive cellular maps that capture multiple regulatory layers. Development of temporal modeling approaches will enable reconstruction of differentiation trajectories with improved resolution, potentially revealing the sequence of molecular events driving lineage decisions. Finally, the application of these integrative frameworks to longitudinal clinical samples will bridge the gap between fundamental biology and therapeutic applications, potentially identifying cellular biomarkers of treatment response or disease progression [5] [30].

The scAtlasVAE framework, with its robust handling of batch effects, sophisticated integration of TCR data, and scalable architecture for atlas-level analyses, establishes a new standard for computational immunology. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve and datasets expand, such integrative approaches will be increasingly essential for extracting meaningful biological insights from the complexity of the immune system. The released reference atlases and computational tools provide the research community with immediate resources to advance our understanding of CD8+ T cell biology in health and disease [5] [30] [31].

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our understanding of cellular heterogeneity, particularly within the immune system. For CD8+ T cells, which play critical roles in cancer immunity, autoimmunity, and infectious diseases, scRNA-seq reveals vast transcriptional diversity that correlates with functional states like exhaustion, memory, and effector differentiation. However, interpreting new scRNA-seq data against established references remains challenging. This guide provides a comprehensive technical framework for utilizing Projecting T cell In vivo Layered states (ProjecTILs), a computational method for projecting new query datasets onto well-annotated reference atlases of CD8+ T cells. We detail experimental protocols, analytical workflows, and visualization strategies to enable researchers to accurately classify T cell states, identify novel populations, and derive biological insights within the context of human CD8+ T cell atlas research.

The interpretation of single-cell data from CD8+ T cells is fundamentally enhanced by comparison to established reference atlases. Exhausted CD8+ T cells (TEX) in cancer and chronic infections undergo profound epigenetic and transcriptional reprogramming [4]. Studies have identified critical transcription factors like IRF8 that reorganize the three-dimensional genome during T cell exhaustion, creating distinct chromatin topological structures that define this dysfunctional state [4]. Similarly, in autoimmune contexts like Type 1 Diabetes, disease-specific CD8+ T cell clonal expansion and the emergence of transcriptionally distinct populations like double-negative T cells highlight the complex heterogeneity within pathological T cell responses [36].

ProjecTILs addresses key challenges in single-cell analysis by:

- Standardizing cell state annotation across datasets and laboratories

- Enabling discovery of novel or perturbed states in experimental conditions

- Facilitating integration of new data with published references without batch effect correction

- Providing quantitative assessment of population frequency changes across conditions

Core Principles of the ProjecTILs Methodology

Algorithmic Foundation

ProjecTILs operates on the principle of label transfer through reference projection, using a curated reference atlas as a stable coordinate system for classifying new cells. The method employs canonical correlation analysis (CCA) to identify shared correlation structures between reference and query datasets, followed by nearest-neighbor classification in the reduced dimensional space.

Reference Atlas Construction

A high-quality reference begins with integrated scRNA-seq data from multiple studies representing diverse biological conditions. The reference must encompass:

- Multiple tissue sources (tumor, peripheral blood, lymph nodes)

- Diverse disease states (cancer, chronic infection, autoimmunity)

- Comprehensive state annotations (naïve, effector, memory, exhausted, precursor)

Experimental Protocols for Reference-Quality Data Generation

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Library Preparation

Cell Isolation and Viability

- Tissue dissociation: Use gentle enzymatic digestion (e.g., Liberase TL) for tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) isolation with minimal stress-induced transcriptional changes

- Magnetic enrichment: Employ CD8+ positive selection kits (e.g., Miltenyi MicroBeads) to enrich target populations to >90% purity

- Viability assessment: Confirm >85% viability via trypan blue exclusion or fluorescent viability dyes before loading on scRNA-seq platforms

Library Construction and Sequencing

- Platform selection: 10x Genomics Chromium platform recommended for high cell throughput and consistent data quality

- Cell loading: Target 5,000-10,000 cells per channel to minimize multiplets while maintaining cost efficiency

- Sequencing depth: Aim for 50,000-100,000 reads per cell to ensure adequate gene detection

- Sequence parameters: 28bp read 1 (cell barcode + UMI), 90bp read 2 (transcript), and 10bp i7 index

Quality Control Metrics

Table 1: Quality Control Thresholds for scRNA-seq Data

| Parameter | Minimum Threshold | Optimal Range | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cells Recovered | >3,000 per sample | 5,000-10,000 | Cell Ranger count statistics |

| Median Genes per Cell | >1,000 | 2,000-4,000 | Scater package (R) |

| Mitochondrial RNA % | <20% | <10% | Percentage of MT-genes |

| Ribosomal RNA % | <30% | 5-15% | Percentage of RPL/RPS genes |

| Total UMIs per Cell | >10,000 | 20,000-50,000 | Cell Ranger count statistics |

Computational Workflow for ProjecTILs Analysis

Data Preprocessing and Normalization

SC RNA-seq Data Processing Pipeline

Reference Projection and Label Transfer

Reference Atlas Projection Workflow

Key Analytical Steps

- Feature Selection: Identify highly variable genes shared between reference and query

- Dimensionality Reduction: Project query data into reference CCA space

- k-Nearest Neighbor Classification: Assign reference-derived labels based on closest neighbors in projection space

- Confidence Scoring: Calculate prediction scores for each cell's state assignment

- Visual Validation: Assess projection quality through UMAP visualization

Quantitative Data Analysis and Interpretation

Population Frequency Analysis

Table 2: CD8+ T Cell State Proportions Across Conditions

| Cell State | Healthy Donor (%) | Cancer (Pre-treatment) (%) | Cancer (Post-immunotherapy) (%) | Key Marker Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve | 45.2 ± 5.1 | 12.3 ± 3.2 | 15.7 ± 4.1 | CCR7, LEF1, TCF7 |

| Stem-like Memory | 18.7 ± 2.8 | 8.5 ± 1.9 | 22.4 ± 3.5 | TCF1, IL7R, CD27 |

| Effector | 25.4 ± 3.5 | 15.2 ± 2.7 | 18.9 ± 2.9 | GZMB, PRF1, IFNG |

| Exhausted | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 45.8 ± 6.3 | 28.5 ± 4.7 | PDCD1, HAVCR2, LAG3 |

| Cytotoxic HLADR+ | 7.6 ± 1.8 | 18.2 ± 3.1 | 14.5 ± 2.8 | GZMK, HLA-DRA, CCL5 |

Differential Abundance Testing

Statistical assessment of population changes across conditions uses generalized linear mixed models to account for donor variability. Significance thresholds: FDR < 0.05 and fold-change > 1.5.

Advanced Applications in CD8+ T Cell Research

Mapping Developmental Trajectories

ProjecTILs enables reconstruction of T cell differentiation pathways by ordering projected cells along pseudotime trajectories. This reveals transitions between states, such as the differentiation from stem-like TCF1+ precursors to terminally exhausted T cells [4].