Decoding Immune Defense: A Network Analysis Guide to Immune Repertoire Architecture

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying network analysis to dissect the complex architecture of adaptive immune repertoires.

Decoding Immune Defense: A Network Analysis Guide to Immune Repertoire Architecture

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying network analysis to dissect the complex architecture of adaptive immune repertoires. It covers foundational principles of immune receptor diversity and the biological rationale for network-based approaches, details practical methodologies from single-cell sequencing to high-performance computing, addresses common experimental and computational challenges, and explores validation frameworks and comparative analyses across health and disease states. By integrating cutting-edge computational strategies with immunological insight, this resource aims to bridge the gap between high-throughput sequencing data and biologically meaningful interpretation for therapeutic discovery.

The Blueprint of Immunity: Foundational Concepts in Immune Repertoire Networks

Adaptive Immune Receptor Repertoire sequencing (AIRR-seq) represents a transformative approach for in-depth analysis of the immune system, enabling comprehensive profiling of T-cell and B-cell receptor repertoires. The development of high-throughput sequencing technologies has created a new frontier for systematically studying the adaptive immune system's dynamics, selection, and pathology [1]. The Adaptive Immune Receptor Repertoire (AIRR) Community was established to develop standards for AIRR-seq studies to facilitate analysis and sharing of these complex datasets [1] [2].

The immune repertoire comprises the collection of distinct B-cell and T-cell clones found in an individual, each associated with a unique antigen receptor—either a B-cell receptor (BCR/immunoglobulin) or T-cell receptor (TR) [1]. The genetic sequences encoding these receptors achieve remarkable diversity through recombination of variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) gene segments, with additional diversification in BCRs through somatic hypermutation (SHM) [1] [3]. The complementarity determining region 3 (CDR3), which encompasses the V(D)J junctions, serves as the most variable portion of the antigen-binding site and acts as a unique molecular fingerprint for each clonal lineage [3] [4].

AIRR-seq has emerged as a powerful method for comparing immune responses across different individuals, disease conditions, and timepoints, enabling researchers to identify clonal expansions, track specific B- or T-cell populations, and understand immune evolution at unprecedented resolution [1]. This technology not only enhances our ability to understand immune responses but also informs diagnostic approaches and therapeutic development across numerous fields including infectious diseases, autoimmunity, cancer immunology, and vaccine development [1] [5].

Technical Foundations and Methodologies

Experimental Design Considerations

Successful AIRR-seq experiments require careful planning across multiple dimensions. Key considerations include subject selection, sample types, processing methods, and appropriate controls [1]. Studies on humans most commonly utilize peripheral blood, but other samples such as tissue biopsies, bone marrow aspirates, cerebrospinal fluid, or bronchoalveolar lavage can provide important insights, particularly in disease-specific contexts [1].

Sample processing represents a critical factor in experimental design. Bulk sequencing methods can utilize formalin-fixed, lysed, or non-viably cryopreserved samples, though fixation significantly reduces nucleic acid quality and may require specialized protocols [1]. For single-cell methods, viable cells are essential, typically consisting of either freshly isolated or properly cryopreserved cells [1]. Cell sorting or enrichment techniques can selectively recover cells of interest but may result in significant sample loss [1].

The choice between genomic DNA (gDNA) and messenger RNA (mRNA) templates represents another fundamental decision point. gDNA offers advantages in stability and more accurate cellular quantification, as each cell contains only one successfully rearranged V(D)J sequence [3]. Conversely, mRNA templates provide higher copy numbers per cell and functional expression information but introduce challenges related to RNA stability and potential reverse transcription errors [3]. DNA-based approaches are particularly valuable for accurate quantification of clonal expansion and tissue density, while RNA-based methods reflect functional activation states [6].

Library Preparation Strategies

Two primary amplification methods dominate AIRR-seq library preparation: multiplex PCR (mPCR) and 5' Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (5'RACE). Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations:

Multiplex PCR employs mixtures of primers to capture multiple V gene regions and can be used with both gDNA and cDNA templates [3]. However, this method may introduce amplification bias due to varying primer efficiencies and cross-reactivity [3]. 5'RACE PCR utilizes gene-specific primers at the 3' end of transcripts, reducing amplification bias but introducing dependency on reverse transcription efficiency and potential bias toward shorter 5'UTR regions [3].

The incorporation of Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) represents a crucial advancement for controlling amplification bias and sequencing errors. UMIs enable bioinformatic correction of PCR duplicates and provide more accurate quantification of initial template abundance [3].

Bulk versus Single-Cell Sequencing

AIRR-seq approaches fundamentally divide into bulk and single-cell methodologies, each with distinct applications and limitations:

Table 1: Comparison of Bulk and Single-Cell AIRR-seq Approaches

| Feature | Bulk Sequencing | Single-Cell Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Input | 1,000 to hundreds of thousands of cells | Typically <20,000 cells due to cost constraints |

| Chain Pairing | Loses heavy/light (BCR) or alpha/beta (TCR) pairing | Retains native chain pairing information |

| Primary Applications | Global repertoire analysis, diversity assessment, clonal tracking | Antigen specificity studies, lineage reconstruction, rare cell characterization |

| Throughput | High-throughput for population-level analysis | Lower throughput, often focused on specific subsets |

| Cost Considerations | More cost-effective for large-scale studies | Higher per-cell cost, limiting scale |

Bulk sequencing provides comprehensive overviews of repertoire composition and diversity but loses pairing information between receptor chains [1]. Single-cell approaches preserve this critical pairing information, enabling reconstruction of complete antigen receptors but at the expense of lower cell throughput and higher costs [1]. A tiered approach combining both methods may be optimal for certain research questions, using bulk sequencing for comprehensive profiling followed by single-cell analysis for detailed investigation of specific populations [1].

Analytical Frameworks and Network Analysis

Data Processing and Standardization

The AIRR Community has developed standardized data representations and protocols to promote interoperability and reproducible analysis of AIRR-seq data [2]. These standards include minimal metadata requirements (MiAIRR), standardized file formats for annotated rearrangement data, and application programming interfaces (APIs) for data sharing [2]. The tab-delimited Rearrangement schema format has been adopted by numerous analysis tools and repositories, facilitating cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses [2].

Computational processing of AIRR-seq data typically involves multiple stages: raw read processing and quality control, sequence assembly and error correction, V(D)J gene alignment and annotation, clonotype definition, and downstream analysis [5]. Tools such as Immcantation provide comprehensive frameworks implementing these steps according to community best practices [5]. For specialized applications like tumor immunology, methods such as TRUST4 enable inference of immune repertoires directly from bulk RNA-seq data, leveraging misaligned reads that span V(D)J junctions [4].

Network Analysis of Immune Repertoire Architecture

Network analysis provides a powerful framework for characterizing the architecture of immune repertoires beyond traditional diversity metrics. This approach clusters T-cell or B-cell receptor sequences based on similarity, typically using Hamming distance or other sequence similarity measures [7]. Unlike frequency-based diversity measures, sequence similarity architecture captures frequency-independent clonal relationships, revealing how immune receptor sequences are organized within antigenic space [7].

The Network Analysis of Immune Repertoire (NAIR) pipeline exemplifies this approach, employing network properties to quantify repertoire architecture and identify disease-associated TCR clusters [7]. This method enables identification of both "public" or shared clones (identical CDR3 sequences across individuals) and "convergent" clusters (structurally similar sequences recognizing common antigens) [7]. By incorporating both sequence similarity and clonal abundance, network analysis can identify antigen-driven responses and reveal repertoire features correlated with clinical outcomes [7].

Advanced network methods integrate additional dimensions such as generation probability (pgen), which estimates how likely a specific receptor sequence is to be generated through V(D)J recombination [7]. This helps distinguish antigen-driven clonotypes from those that appear frequently due to higher generation probabilities. When combined with Bayesian statistical approaches, these methods can identify disease-specific TCRs with high confidence [7].

Integrated Analysis Platforms

Emerging platforms enable integrated analysis of multiple immune repertoire components. The Automated Immune Molecule Separator (AIMS) software provides uniform analysis of TCR, MHC, peptide, antibody, and antigen sequence data, identifying biophysical differences and interaction patterns across complementary receptor-antigen pairs [8]. This integrated approach facilitates identification of key interaction hotspots and enables direct comparisons across different immune repertoire subsets [8].

AIMS employs specialized encoding schemes that capture structural features of immune molecules without requiring explicit experimental structures [8]. For TCR sequences, a "central alignment" scheme focuses on CDR loop regions most likely to contact antigens, while for peptides, a "bulge scheme" emphasizes central residues that typically interact with TCRs [8]. This biophysically-informed encoding enables identification of sequence clusters with potential functional significance.

Applications and Research Reagents

Key Research Applications

AIRR-seq has enabled advances across numerous research domains:

- Infectious Disease: Tracking antigen-specific responses to pathogens like SARS-CoV-2, identifying convergent antibody responses, and monitoring immune memory [7] [5].

- Cancer Immunotherapy: Discovering tumor-reactive TCRs and BCRs, monitoring minimal residual disease, and characterizing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes [1] [4].

- Autoimmune Disorders: Identifying self-reactive clones and characterizing aberrant immune responses in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus [1] [3].

- Vaccine Development: Profiling vaccine-induced immune responses, identifying protective clones, and optimizing vaccine design [1].

- Transplantation Immunology: Monitoring alloreactive responses and graft rejection signatures [7].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AIRR-seq

| Category | Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | gDNA templates | Quantitative cellular measurement | Stable, proportional to cell number, ideal for archival specimens [3] [6] |

| RNA/cDNA templates | Functional expression analysis | Higher template copies per cell, reflects activation state [3] | |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Error correction and quantification | Molecular barcoding for amplification bias correction [3] | |

| Computational Tools | Immcantation Framework | End-to-end AIRR-seq analysis | From raw processing to clonal inference; bulk and single-cell support [5] |

| TRUST4 | Immune repertoire inference from RNA-seq | De novo CDR3 assembly without dedicated immune sequencing [4] | |

| NAIR | Network analysis of repertoires | Sequence similarity clustering and disease-associated clone identification [7] | |

| AIMS | Integrated multi-molecule analysis | Cross-receptor comparison and biophysical property characterization [8] | |

| MiXCR | Assembly and annotation | V(D)J alignment and clonotype calling [7] | |

| Reference Databases | IMGT | Germline gene reference | Curated V, D, J, and C gene sequences [5] |

| iReceptor | AIRR-seq data repository | Data sharing and discovery platform [2] | |

| VDJServer | Computational platform | Cloud-based analysis portal [2] |

Adaptive Immune Receptor Repertoire sequencing has revolutionized our ability to study the immune system at unprecedented depth and scale. The technical foundations of AIRR-seq, encompassing careful experimental design, appropriate template selection, and optimized library preparation, provide the basis for generating high-quality immune repertoire data. The development of standardized data representations and analytical frameworks has enabled robust, reproducible analysis and cross-study comparisons.

Network analysis approaches represent a particularly powerful advancement for characterizing the architecture of immune repertoires, moving beyond traditional diversity metrics to capture sequence similarity relationships and identify disease-associated clusters. These methods, combined with integrated analysis platforms that examine multiple immune molecules simultaneously, are revealing new insights into the fundamental organization of immune responses.

As AIRR-seq technologies continue to evolve and computational methods become increasingly sophisticated, this field holds tremendous promise for advancing our understanding of immune function in health and disease, ultimately enabling new diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines. The ongoing work of the AIRR Community to establish standards and best practices ensures that these powerful technologies will continue to yield biologically meaningful and clinically relevant discoveries.

V(D)J recombination serves as the fundamental genetic mechanism for generating the immense diversity of antibodies and T-cell receptors essential for adaptive immunity. This somatic recombination process leverages a relatively small set of gene segments to create an almost limitless repertoire of antigen binding specificities through combinatorial assembly and junctional diversification. Recent advances in network analysis and high-throughput sequencing have revealed that despite this stochastic process, the resulting immune repertoire architecture exhibits remarkable reproducibility, robustness, and redundancy across individuals. This technical review examines the molecular machinery of V(D)J recombination, quantitative approaches to analyzing repertoire architecture, and the implications of individualized recombination biases for disease susceptibility and therapeutic development.

V(D)J recombination is the somatic recombination mechanism that occurs in developing lymphocytes during early stages of B- and T-cell maturation, representing a defining feature of the adaptive immune system [9]. This process operates through chromosomal breakage and rejoining events that assemble the exons encoding antigen-binding portions of immunoglobulins and T-cell receptors from variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) gene segments [10]. The elegant simplicity of this system leverages a relatively small investment in germline coding capacity into an almost limitless repertoire of potential antigen binding specificities, with roughly 3×10¹¹ combinations possible in humans [9].

The architecture of antibody repertoires is defined by the sequence similarity networks of the clones that compose them, reflecting the breadth of antigen recognition [11]. Understanding this architecture provides critical insights for developing novel therapeutics and vaccines, particularly as analysis moves from pure research toward biomarker discovery and personalized immunotherapies [12]. The integration of network biology approaches with immune repertoire analysis now enables researchers to quantify fundamental principles of repertoire architecture and identify disease-associated signatures across longitudinal samples [13].

Molecular Mechanism of V(D)J Recombination

Recognition and Cleavage

The V(D)J recombinase recognizes conserved DNA sequence elements termed recombination signal sequences (RSS) located adjacent to each V, D, and J coding segment [10]. RSS consist of conserved heptamer and nonamer elements separated by 12 or 23 nucleotides of less conserved "spacer" sequence, with efficient recombination occurring only between RSS with different spacer lengths—the "12/23 rule" [10] [9]. The recombination activating genes RAG1 and RAG2, together with DNA-bending factors HMGB1 or HMGB2, mediate DNA cleavage through a two-step mechanism [10]:

- Nick formation: A single-strand break is introduced between the RSS and the coding flank

- Transesterification: The resulting 3'OH group attacks the opposite strand, forming a hairpin coding end and a blunt signal end

This cleavage mechanism shares similarities with transposition reactions catalyzed by bacterial transposases and HIV integrase, supporting the hypothesis that the RAG proteins evolved from an ancestral transposase [10].

Joining and Diversification

After cleavage, the four DNA ends remain associated with RAG proteins in a post-cleavage complex that directs joining through the classical non-homologous end joining (cNHEJ) pathway [10]. The joining process exhibits characteristic asymmetric processing:

- Signal ends are generally joined with little processing, forming perfect heptamer-to-heptamer fusions

- Coding ends undergo significant processing including hairpin opening by Artemis nuclease, generating palindromic (P) nucleotides, exonuclease trimming, and addition of non-templated (N) nucleotides by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) [10] [9]

Table 1: Key Enzymes in V(D)J Recombination

| Enzyme/Component | Function | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| RAG1/RAG2 | Recognition of RSS, DNA cleavage | Lymphoid-specific |

| HMGB1/HMGB2 | DNA bending, facilitates synapsis | Ubiquitous |

| Artemis | Hairpin opening, endonuclease activity | Ubiquitous (activated by DNA-PK) |

| DNA-PK | DNA end sensing, Artemis activation | Ubiquitous |

| TdT | Addition of N-nucleotides | Lymphoid-specific |

| XRCC4/DNA Ligase IV | Ligation of broken ends | Ubiquitous |

| XLF (Cernunnos) | Stabilization of ligation complex | Ubiquitous |

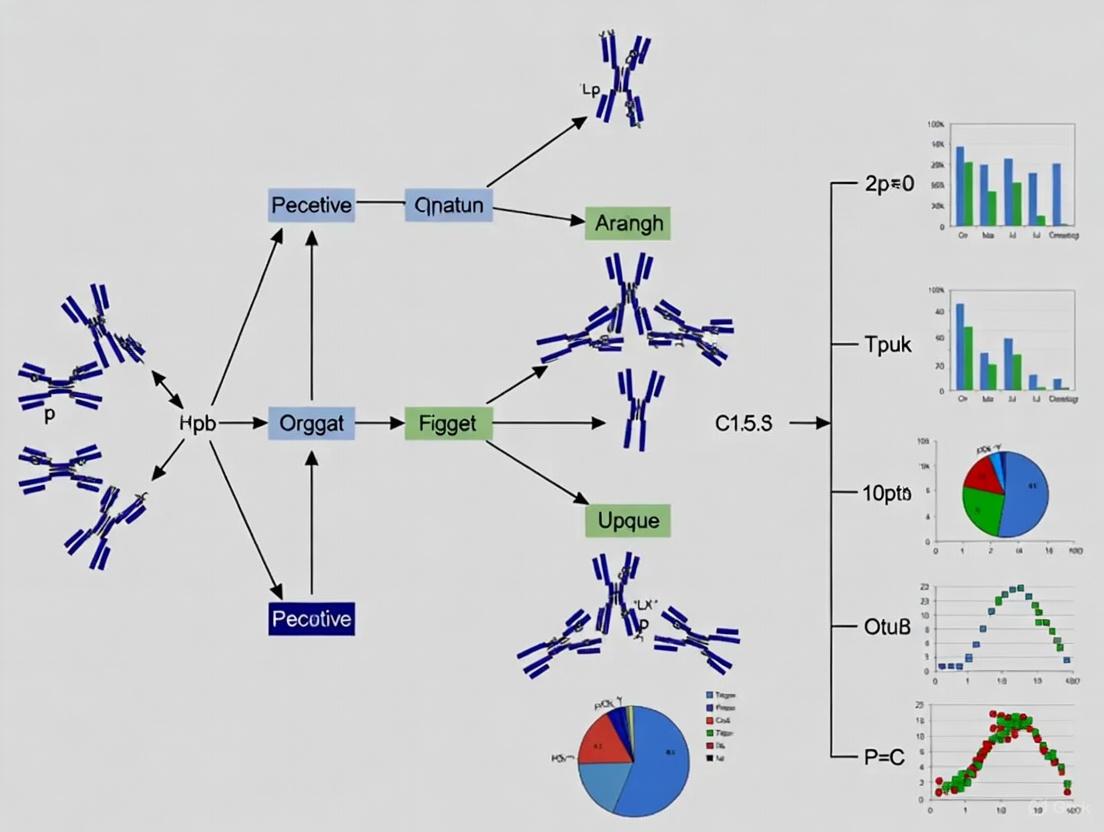

Figure 1: V(D)J Recombination Mechanism

Quantitative Analysis of Immune Repertoire Diversity

Generation Probability and Individualized Recombination Models

The probability of generating a specific immune receptor sequence (Pgen) varies significantly between individuals due to differences in VDJ recombination models [14]. Not only unrelated individuals but also monozygotic twins and inbred mice possess statistically distinguishable immunoglobulin recombination models, suggesting nongenetic modulation of VDJ recombination in addition to genetic factors [14]. This individualized recombination results in orders of magnitude difference in the probability to generate (auto)antigen-specific immunoglobulin sequences between individuals, with profound implications for susceptibility to autoimmune diseases, cancer, and infectious diseases [14].

The DEtection of SYstematic differences in GeneratioN of Adaptive immune recepTOr Repertoires (desYgnator) method uses Jensen-Shannon divergence (JSD) to compare repertoire generation models across individuals, accounting for various sources of noise including synthetic sampling noise, data sampling noise, technical noise, and biological noise [14]. This approach demonstrates that individualized VDJ recombination can bias different individuals toward exploring different AIR sequence spaces.

Network Analysis of Repertoire Architecture

Large-scale network analysis of antibody repertoires has revealed three fundamental principles of architecture: reproducibility, robustness, and redundancy [11]. Construction of sequence similarity networks involves representing complementarity determining region 3 (CDR3) amino acid clones as nodes connected by similarity edges based on Levenshtein distance, with computational challenges addressed through distributed computing platforms like Apache Spark [11].

Table 2: Network Properties of Antibody Repertoires Across B-Cell Development

| B-Cell Stage | Largest Component Size | Average Degree | Edge Count | Centralization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-B cells (pBC) | 46 ± 0.7% | 3 | 230,395 ± 23,048 | ~0 |

| Naïve B cells (nBC) | 58 ± 0.5% | 5 | 1,016,928 ± 67,080 | ~0 |

| Memory plasma cells (PC) | 10 ± 1.6% | 1 | 45 ± 10 | 0.05 |

Network analysis reveals that antibody repertoire architecture is:

- Reproducible across individuals despite high antibody sequence dissimilarity

- Robust to removal of 50-90% of randomly selected clones but fragile to removal of public clones

- Intrinsically redundant with substantial edge redundancy (65-85%) [11]

Advanced tools like the Network Analysis of Immune Repertoire (NAIR) pipeline incorporate sequence similarity networks with clinical outcomes to identify disease-specific TCR clusters and incorporate generation probability with clonal abundance using Bayes factors to filter false positives [7].

Experimental Methodologies and Computational Tools

Immune Repertoire Sequencing and Analysis Workflow

Contemporary immune repertoire analysis employs standardized pipelines for processing high-throughput sequencing data:

Figure 2: Immune Repertoire Analysis Workflow

The MiXCR workflow provides a comprehensive pipeline for immune repertoire analysis, including upstream processing (contig assembly, alignment, error correction), quality control (report generation, alignment metrics), and downstream secondary analysis (somatic hypermutation trees, diversity measures, pairwise distance analysis) [15]. For single-cell data, tools like Cell Ranger and Loupe Browser enable paired V(D)J sequence analysis from individual cells [15].

Computational Tools for Repertoire Analysis

Table 3: Computational Tools for Immune Repertoire Analysis

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| immunarch | Multi-modal immune repertoire analysis in R | Diversity analysis, clonality tracking, V/J usage, machine learning feature engineering | R package [12] |

| MiXCR | Comprehensive repertoire sequence analysis | Advanced error correction, allele inference, species flexibility, supports bulk and single-cell data | Java-based [15] |

| NAIR | Network analysis of immune repertoires | Sequence similarity networks, disease-associated cluster identification, Bayes factor integration | R pipeline [7] |

| GLIPH2 | TCR specificity grouping | Clusters TCRs based on sequence similarity for antigen specificity prediction | Algorithm [7] |

The immunarch package specifically addresses the need for scalable, reproducible analysis pipelines that can handle massive datasets moving from gigabytes to terabytes, with particular focus on biomarker discovery and personalized immunotherapies [12]. Its modular architecture enables diversity analysis, public clonotype assessment, and machine learning-ready feature table construction.

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for V(D)J Recombination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Kits | 10x Genomics 5' Gene Expression | Single-cell immune profiling | Full-length, paired V(D)J sequences from individual cells |

| Antibody Panels | MHC multimers, lineage markers | Cell sorting and phenotyping | Identification of antigen-specific T cells, B cell subsets |

| Enzymatic Reagents | RAG1/RAG2, TdT, Artemis | In vitro recombination assays | Molecular dissection of recombination mechanism |

| NHEJ Components | DNA-PK, XRCC4, DNA Ligase IV | DNA repair studies | Analysis of post-cleavage joining fidelity |

| Computational Resources | Apache Spark, Highcharts | Large-scale network analysis | Distributed computing for similarity matrices, accessible visualization |

Implications for Disease and Therapeutic Development

The architecture of immune repertoires has significant implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing therapeutics. Aberrant V(D)J recombination events can be life-threatening, underlying the genesis of common lymphoid neoplasms [10]. Recent genomewide analyses of lymphoid neoplasms have revealed V(D)J recombination-driven oncogenic events, intensifying interest in regulatory mechanisms responsible for ensuring fidelity during V(D)J recombination [10].

In infectious disease contexts, network analysis of TCR repertoires in COVID-19 subjects demonstrated that recovered individuals had increased diversity and richness above healthy individuals, with skewed VJ gene usage in the TCR beta chain [7]. Such repertoire analysis demonstrates potential as a biomarker for improved diagnosis and disease monitoring.

For HIV research, network-based approaches have identified potential longitudinal biomarkers related to the HIV reservoir, categorized into five groups: HIV-related factors, immunity markers, cellular molecules and soluble factors, host genome factors, and epigenomes [13]. This systematic approach enables tracking of disease progression and reservoir characterization across different stages of infection.

V(D)J recombination represents a sophisticated biological mechanism that balances the generation of immense diversity with maintenance of genomic integrity. The integration of network analysis approaches with high-throughput immune repertoire sequencing has revealed fundamental principles of repertoire architecture that persist despite individualized recombination biases. As computational methods advance to handle increasingly large datasets and multi-modal data integration, the potential grows for identifying robust biomarkers, designing targeted immunotherapies, and understanding disease susceptibility at the individual level. The continued refinement of tools like immunarch, MiXCR, and NAIR will further empower researchers to extract clinically meaningful insights from the complex architecture of immune repertoires.

The mammalian immune system is the epitome of a complex biological network, composed of hierarchically organized genes, proteins, and cellular components that combat external pathogens and monitor internal disease onset [16]. Unlike linear systems, the immune system orchestrates an exquisitely complex interplay of numerous cells, often with highly specialized functions, in a tissue-specific manner [16]. This network perspective is not merely an analytical convenience but reflects fundamental biological reality—immune cells form a distributed network throughout the body, dynamically forming physical associations and communicating through interactions between their cell-surface proteomes [17].

The paradigm of "thinking networks" has emerged as a crucial framework for understanding immune function, from development through effector responses [16]. At its core, this perspective recognizes that immune processes are not governed by isolated molecules or cells, but through highly structured source-target relationships that can be abstracted into nodes and edges, where nodes represent biological entities (genes, proteins, cells) and edges depict connections between them [16]. This network formalism facilitates data integration and enables effective visualization of underlying biological patterns that would remain obscured in reductionist approaches.

The Multi-Scale Nature of Immune Networks

Molecular and Cellular Networks

Immune networks operate across multiple spatial and organizational scales, each with distinct characteristics and functional implications:

| Network Scale | Components (Nodes) | Interactions (Edges) | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intracellular | Genes, transcription factors, signaling proteins | Transcriptional regulation, protein-protein interactions | Determines cell differentiation, activation states, and functional plasticity [16] |

| Intercellular | Immune cells (T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, etc.) | Receptor-ligand interactions, cell-cell contacts | Coordinates population-level responses, immune synapse formation [17] |

| Systemic | Distributed immune populations across tissues | Cellular migration, chemokine signaling | Enables body-wide immune surveillance and coordinated response to threats [17] |

At the molecular level, the physical wiring diagram of the human immune system comprises diverse arrays of cell-surface proteins that organize immune cells into interconnected cellular communities, linking cells through physical interactions that serve both signaling communication and structural adhesion functions [17]. A systematic survey of these interactions revealed that 57% of binding pairs are unique, without either protein having another binding partner, while the largest interconnected group features integrins and other adhesion molecules [17].

Quantitative Principles of Immune Connectivity

Recent advances have enabled not only the systematic mapping but also the quantitative characterization of immune network parameters. Integration of binding affinities with proteomics expression data has revealed fundamental principles governing immune cell interactions [17]:

- The distribution of surface interactions has affinities centered in the low micromolar range, with a long tail of higher-affinity interactions

- Higher expression levels show a weak negative correlation with binding strength

- Immune activation triggers an "affinity switch" where higher-affinity interactions predominate in inflamed states, replaced by more transient interactions in resting states

These quantitative principles enable the development of mathematical models that predict cellular connectivity from basic biophysical parameters. By applying equations based on the law of mass action, researchers can compute how the overall probability of binding between two cell types emerges from the distinct spectrum of cell-surface receptors that connect them [17].

Analytical Frameworks for Immune Network Reconstruction

Technological Foundations

The reconstruction of immune networks relies on advanced high-throughput technologies that provide system-wide measurements of immune components:

Figure 1. Workflow for immune network reconstruction, from data generation to network inference. SAVEXIS (Scalable Arrayed Multi-valent Extracellular Interaction Screen) enables systematic surveying of surface protein interactions [17].

These technologies have been particularly transformative for understanding the heterogeneous nature of immune cells, which is especially pronounced in the immune system with its vast number of constituents and their functional states [16]. Single-cell technologies have revealed transcriptional heterogeneity and lineage commitment in myeloid progenitors [16], while methods like SAVEXIS have enabled systematic mapping of direct protein interactions across libraries encompassing most surface proteins detectable on human leukocytes [17].

Computational Methodologies for Network Inference

The computational frameworks for inferring networks from omics data fall into several major categories:

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Key Features | Applications in Immunology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-expression Networks | WGCNA [16] | Based on Pearson or Spearman correlations | Identifies coordinately expressed gene modules in hematopoiesis [16] |

| Regulon Inference | ARACNe, SJARACNe [16] | Uses mutual information and data-processing inequality | Reconstructs transcriptional regulatory networks [16] |

| Master Regulator Analysis | VIPER, NetBID [16] | Infers protein activities from regulons | Identifies hidden drivers of transcriptional responses [16] |

| Sequence Similarity Networks | NAIR [7] | Clusters TCRs based on Hamming distance | Identifies disease-associated T-cell clusters [7] |

These methodologies address distinct challenges in network inference. For example, co-expression relations are often indirect or redundant, which algorithms like ARACNe overcome by using mutual information to capture nonlinear gene-gene relations and applying data-processing inequality to remove redundant edges [16]. In practice, the most valuable application of these networks is not singling out particular edges but identifying regulons—sets of genes regulated by a transcription factor that are presumed responsible for common biological functions [16].

The Network Analysis of Immune Repertoire (NAIR) Pipeline

Framework for TCR Repertoire Analysis

The Network Analysis of Immune Repertoire (NAIR) represents a specialized application of network principles to T-cell receptor sequencing data [7]. This pipeline addresses the unique challenge of analyzing the highly diverse and dynamic T-cell immune repertoire, which spans several orders of magnitude in size, physical location, and time [7].

Figure 2. The NAIR pipeline for T-cell receptor repertoire network analysis. TCRs are clustered based on sequence similarity, adding a complementary layer to repertoire diversity analysis [7].

Unlike immune repertoire diversity based on frequency profiles of individual clones, sequence similarity architecture captures frequency-independent clonal sequence similarity relations [7]. This approach recognizes that conserved sequences in the complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) directly influence antigen recognition breadth: the more different receptors are, the larger the antigen space covered [7].

Key Methodological Steps in NAIR

The NAIR pipeline implements several sophisticated algorithms for identifying biologically significant T-cell clusters:

Network Construction: Pairwise distance matrices of TCR amino acid sequences are calculated using Hamming distance, with networks formed by connecting sequences below a specified similarity threshold [7].

Disease-Associated Cluster Identification:

- TCRs are identified based on their presentation frequency in disease subjects compared to healthy controls using Fisher's exact test

- COVID-19-associated TCRs are defined as those shared by at least 10 samples with sequence length ≥6 amino acids

- Network analysis expands these seeds to include TCRs within a Hamming distance ≤1 [7]

Public Cluster Identification:

- The largest clusters or single nodes with high abundance are selected from each sample

- Representative clones with the largest counts are identified within each cluster

- A new network is built from selected clones, with clusters containing clones from different samples considered public clusters [7]

This approach incorporates both generation probability (pgen)—which evaluates how likely specific amino acid sequences are to be generated—and clonal abundance using Bayes factor to distinguish antigen-driven clonotypes from genetically naïve predetermined clones [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for Immune Network Analysis

Successful implementation of network analysis in immunology requires specialized reagents and computational resources:

| Resource Category | Specific Solutions | Application in Network Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, CITE-seq [16] | Provides single-cell resolution data for network node definition |

| Interaction Screening | SAVEXIS method [17] | Systematically maps extracellular protein-protein interactions |

| Computational Tools | ARACNe, SJARACNe, VIPER, NetBID [16] | Infers regulatory networks from expression data |

| Specialized Immunological | GLIPH2, ImmunoMap, NAIR [7] | Analyzes TCR repertoire similarity networks |

| Reference Datasets | Immunological Genome Project [16], MIRA database [7] | Provides ground truth for network validation |

These resources enable the generation of comprehensive datasets such as the quantitative immune cell interactome, which integrates proteomics expression with binding kinetics to predict cellular connectivity from basic principles [17]. The MIRA (Multiplex Identification of Antigen-Specific T-Cell Receptors Assay) database, containing over 135,000 high-confidence SARS-CoV-2-specific TCRs, provides essential validation data for network predictions [7].

Biological Insights from Immune Network Analysis

Network Principles in Hematopoiesis and Immunity

Application of network analysis to immune processes has revealed fundamental organizational principles:

Myeloid cells as network hubs: Across multiple primary and secondary lymphoid tissues, myeloid-lineage cells consistently show higher network centrality scores despite expressing similar numbers of surface ligands as other cell types, suggesting they serve as central integrators of local interactions in their tissue niche [17].

Regulatory network dynamics in hematopoiesis: Transcriptional network analysis of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells has revealed the regulatory transitions that accompany lineage commitment, with specific transcription factors acting as master regulators that drive differentiation along particular pathways [16].

Affinity switching during immune activation: Quantitative analysis of receptor interaction networks shows that immune activation triggers a transition where higher-affinity interactions predominate in inflamed states, replaced by more transient interactions in resting states [17].

Clinical Applications in Disease and Therapeutics

Network approaches have identified clinically relevant immune signatures across various disease contexts:

COVID-19-specific TCR clusters: NAIR analysis of COVID-19 subjects identified disease-associated TCR clusters that correlated with clinical outcomes, with recovered subjects showing increased diversity and richness above healthy individuals [7].

Tumor microenvironment networks: Integration of single-cell expression data with interaction networks has revealed how phagocyte populations shift their cellular contacts within tumor microenvironments, including upregulation of specific ligands like APLP2 and APP in kidney tumors [17].

Predictive models for immunotherapy: Network analysis of T-cell dynamics across multiple cancers through scRNA-seq and immune profiling has enabled the development of prediction models for response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy [18].

These clinical applications demonstrate how network perspectives move beyond individual biomarkers to capture system-level properties that better predict clinical outcomes and therapeutic responses.

The biological rationale for network analysis in immunology rests on the fundamental recognition that the immune system is inherently a multi-scale network, from intracellular regulatory circuits to intercellular communication systems. The transition from sequences to systems represents more than a methodological shift—it embodies a conceptual transformation in how we understand immune organization, function, and dysregulation.

Network approaches provide the analytical framework necessary to address the core challenge of immunology: understanding how highly diverse and dynamic cellular populations coordinate their behaviors to achieve appropriate immune responses across tissues and time. As these methods continue to evolve, particularly through integration of single-cell technologies and spatial mapping, they promise to reveal increasingly sophisticated principles of immune network organization with significant implications for diagnostic strategies and therapeutic interventions.

Network analysis of immune repertoires has emerged as a powerful methodology for decoding the complex architecture of adaptive immune responses. By representing antibody or T-cell receptor sequences as nodes connected by similarity edges, this approach reveals fundamental organizational principles that govern immune function. This technical guide examines three core architectural principles—reproducibility, robustness, and redundancy—that define the sequence space architecture of immune repertoires. We detail experimental protocols for large-scale network construction, provide quantitative frameworks for measuring these principles, and discuss implications for therapeutic development and clinical translation. The findings demonstrate how network-based statistical frameworks applied to comprehensive repertoire sequencing data (>100,000 unique sequences) can uncover universal design principles that persist across individuals despite high sequence-level diversity.

The adaptive immune system generates remarkable diversity through somatic recombination of V(D)J gene segments, creating vast repertoires of B-cell and T-cell receptors capable of recognizing countless pathogens. The architecture of these repertoires—defined by the similarity relationships between receptor sequences—plays a crucial role in determining immune protection breadth and function. The complementarity determining region 3 (CDR3) serves as the primary determinant of antigen specificity, making its sequence similarity landscape particularly informative for understanding repertoire architecture [11].

Traditional analysis of immune repertoires has focused on diversity metrics and clonal expansion patterns. However, network analysis provides a complementary approach that captures frequency-independent clonal sequence similarity relations, offering insights into the fundamental construction principles of immune repertoires [7]. This approach represents CDR3 amino acid sequences as nodes in a network, connected by edges when their sequences are sufficiently similar (e.g., by Levenshtein distance or Hamming distance) [11]. Through large-scale application of this methodology, researchers have identified three fundamental principles that define immune repertoire architecture: reproducibility, robustness, and redundancy [19].

These principles have significant implications for both basic immunology and therapeutic development. They inform our understanding of how immune systems maintain functionality across individuals, respond to pathogenic challenges, and fail in disease states. For drug development professionals, these principles offer frameworks for evaluating vaccine efficacy, developing immunotherapies, and identifying disease-associated receptor signatures [7].

Computational Framework and Methodology

High-Performance Computing Platform

Large-scale network analysis of immune repertoires requires specialized computational infrastructure due to the enormous scale of the distance matrix calculations. For a repertoire containing ≈10ⶠclones, the size of the all-against-all sequence distance matrix reaches ≈10¹², making conventional computing approaches intractable [11].

- Distributed Computing Framework: The implementation utilizes Apache Spark distributed computing framework to partition computations across a cluster of machines, enabling parallel processing of massive sequence datasets

- Similarity Network Construction: Networks are built as Boolean undirected graphs where nodes (antibody CDR3 sequences) are connected if and only if they have a Levenshtein distance (LD) of n, where n typically ranges from 1 to 12. The base similarity layer (LD1) connects sequences differing by only one amino acid

- Computational Performance: A network of 1.6 million nodes can be constructed in approximately 15 minutes using 625 computational cores, compared to months of computation without parallelization [11]

Network Analysis of Sequence Similarity

The construction of sequence similarity networks follows a standardized workflow:

- Data Acquisition: Bulk high-throughput sequencing of B-cell or T-cell receptor repertoires using next-generation sequencing platforms

- Sequence Preprocessing: Annotation of TCR or BCR locus rearrangements using frameworks like MiXCR, filtering of non-productive reads, and removal of sequences with low read counts [7]

- Distance Calculation: Computation of pairwise amino acid sequence similarity using Levenshtein distance (for BCRs) or Hamming distance (for TCRs)

- Network Formation: Application of thresholding to create edges between sequences within specified distance thresholds, followed by cluster identification using community detection algorithms

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculation of global (repertoire-level) and local (clonal-level) network properties to characterize architecture [7]

Key Network Metrics and Properties

Immune repertoire networks are characterized through both global and local properties:

Table 1: Key Network Properties for Immune Repertoire Analysis

| Property Type | Metric | Biological Interpretation | Measurement Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Properties | Largest Component Size | Degree of repertoire connectivity | Percentage of nodes in largest connected component |

| Number of Edges | Overall clonal interconnectedness | Total edges in similarity network | |

| Centralization | Concentration of connectivity | Degree to which network revolves around central nodes | |

| Assortativity | Preference for nodes to connect to similar nodes | Correlation coefficient of degrees between connected nodes | |

| Local Properties | Degree | Number of similar clones for a given sequence | Count of edges connected to a node |

| Betweenness | Importance as connector in network | Number of shortest paths passing through node | |

| Clustering Coefficient | Local interconnectedness | Likelihood that neighbors of a node are connected |

These metrics provide the quantitative foundation for evaluating the reproducibility, robustness, and redundancy principles in immune repertoire architecture.

The Three Architectural Principles

Reproducibility

Concept Definition: Reproducibility in immune repertoire architecture refers to the conservation of global network properties across individuals despite high divergence in specific antibody sequences.

Experimental Evidence: Studies of antibody repertoires across murine B-cell developmental stages (pre-B cells, naïve B cells, and memory plasma cells) demonstrate remarkable cross-individual consistency in network structure. Although antibody sequence diversity varies significantly between mice (74-85% unique clones per individual), global network measures show negligible variation [11]:

- Edge Conservation: The number of edges among clones varied minimally (EₚBĆ = 230,395 ± 23,048; EₙBĆ = 1,016,928 ± 67,080)

- Component Size Stability: The size of the largest connected component remained consistent within B-cell stages (pBC = 46 ± 0.7%; nBC = 58 ± 0.5%)

- Architecture Convergence: This conservation suggests that VDJ recombination, while stochastic at the sequence level, generates repertoires with convergent architectural properties across individuals

Methodological Application: The NAIR (Network Analysis of Immune Repertoire) pipeline leverages this principle to identify disease-associated TCR clusters by comparing network properties between patient cohorts, such as COVID-19 patients versus healthy donors [7].

Robustness

Concept Definition: Robustness describes the resilience of repertoire architecture to perturbations, specifically the removal of randomly selected clones versus targeted removal of public clones.

Experimental Evidence: Large-scale network analysis reveals that antibody repertoire architecture remains intact despite substantial random clone removal:

- Random Deletion Tolerance: Networks maintain architectural integrity with removal of 50-90% of randomly selected clones

- Public Clone Fragility: Targeted removal of public clones (sequences shared among individuals) rapidly disrupts network connectivity and architecture [19]

- Functional Interpretation: This differential fragility suggests that public clones serve as critical hubs maintaining repertoire connectivity, while random clones provide expendable diversity

Therapeutic Implications: The robustness principle informs therapeutic design by identifying critical public clones that may be essential for maintaining immune functionality. This has particular relevance for vaccine development, where inducing robust, public responses may confer more durable protection [7].

Redundancy

Concept Definition: Redundancy refers to the built-in capacity of immune repertoires to maintain functionality through multiple similar sequences capable of recognizing the same antigens.

Experimental Evidence: Analysis of sequence similarity networks demonstrates extensive clustering of receptors with similar specificities:

- Degenerate Recognition: Multiple distinct CDR3 sequences can recognize identical epitopes, creating functional redundancy in antigen recognition

- Cluster Organization: Related sequences form interconnected clusters in similarity networks, providing built-in backup systems if specific clones are lost

- Architectural Efficiency: This redundant organization ensures comprehensive antigen coverage while minimizing the risk of gap creation from random clone loss

Translational Application: The redundancy principle guides the identification of disease-associated TCR clusters through customized search algorithms that identify groups of similar sequences significantly associated with clinical status, even when individual sequences are rare [7].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Large-Scale Network Construction Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Isolate B cells or T cells from blood or tissue samples

- Extract genomic DNA or RNA for receptor sequencing

- Amplify TCR or BCR loci using multiplex PCR approaches

- Sequence using high-throughput platforms (Illumina)

Data Processing:

- Annotate V(D)J rearrangements using MiXCR framework with species-specific references

- Filter non-productive reads and sequences with fewer than two read counts

- Translate nucleotide sequences to amino acids for CDR3 analysis

- Define clones by unique CDR3 amino acid sequences

Network Construction:

- Calculate pairwise distance matrix using Levenshtein distance (BCR) or Hamming distance (TCR)

- Apply distance threshold (typically LD1 for single amino acid differences)

- Construct Boolean undirected network where edges represent sufficient similarity

- Identify connected components using fast greedy algorithm

Network Analysis Workflow for Immune Repertoires

Disease-Associated Cluster Identification

The NAIR pipeline implements a customized workflow for identifying disease-associated TCR clusters:

- Public Clone Identification: Calculate the number of samples sharing each TCR sequence

- Statistical Filtering: Apply Fisher's exact test (p < 0.05) to identify TCRs with significantly different frequency between disease and control groups, requiring presence in at least 10 samples

- Length Filtering: Retain only TCRs with CDR3 length ≥ 6 amino acids

- Cluster Expansion: For each disease-associated TCR, identify similar sequences (Hamming distance ≤ 1) within the same samples

- Classification: Define COVID-only TCR clusters (present only in disease samples) and COVID-associated TCR clusters (present in both groups)

- Network Integration: Generate comprehensive network across all disease-associated TCRs and assign global cluster membership [7]

Public Cluster Detection Workflow

Identifying shared clusters across samples follows a distinct protocol:

- Individual Network Construction: Build similarity networks for each sample independently

- Cluster Selection: Select the top K largest clusters or single nodes with high abundance (count > 100) from each sample

- Representative Identification: Within each cluster, identify the representative clone with the largest count

- Skeleton Network Construction: Build a new network from representative clones across samples

- Cluster Definition: Define skeleton public clusters containing representatives from different samples

- Cluster Expansion: Expand each skeleton public cluster to include all clones belonging to the same cluster in original samples [7]

Quantitative Data and Analysis

Network Properties Across B-Cell Development

Table 2: Network Architecture Across Murine B-Cell Developmental Stages

| B-Cell Stage | Number of Edges | Largest Component (%) | Average Degree | Centralization | Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-B Cells (pBC) | 230,395 ± 23,048 | 46 ± 0.7% | 3 | ~0 | ~0 |

| Naïve B Cells (nBC) | 1,016,928 ± 67,080 | 58 ± 0.5% | 5 | ~0 | ~0 |

| Memory Plasma Cells (PC) | 45 ± 10 | 10 ± 1.6% | 1 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

The data reveals profound architectural differences across B-cell development. Pre-B cell and naïve B cell networks show homogeneous connectivity with high interconnectedness, while plasma cell networks are significantly more disconnected and centralized, suggesting antigen-driven selection creates more specialized, focused architectures [11].

Robustness Quantification

Network robustness is quantitatively assessed through systematic node removal experiments:

Table 3: Robustness to Clone Removal in Antibody Repertoire Networks

| Removal Type | Removal Percentage | Architectural Impact | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Removal | 50-90% | Minimal disruption | Global network properties remain stable |

| Public Clone Removal | 10-30% | Significant fragmentation | Rapid disintegration of largest connected component |

| Hub Removal | 5-15% | Moderate disruption | Decreased connectivity but maintained architecture |

The differential impact demonstrates that repertoire architecture is robust to random perturbations but fragile to targeted removal of structurally important clones, revealing the non-random organization of immune repertoires [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Key Reagents and Tools for Immune Repertoire Network Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| MiXCR Framework | Annotation of TCR/BCR rearrangements | Processing raw sequencing data into annotated receptor sequences [7] |

| Apache Spark | Distributed computing platform | Enabling large-scale distance matrix calculations [11] |

| Igraph Library | Network analysis and visualization | Identifying connected components and calculating network metrics [7] |

| GLIPH2 | TCR sequence clustering based on similarity | Grouping TCRs with potential shared specificity [7] |

| ImmunoMap | Antigen-specificity prediction using database approaches | Identifying potential antigen targets for TCR sequences [7] |

| MIRA Database | Repository of antigen-specific TCRs | Validating disease-associated TCR clusters [7] |

| Hamming/Levenshtein Distance | Sequence similarity quantification | Determining edge formation in network construction [7] [11] |

| Amantanium Bromide | Amantanium Bromide, CAS:58158-77-3, MF:C25H46BrNO2, MW:472.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Allantoxanamide | Allantoxanamide, CAS:69391-08-8, MF:C4H4N4O3, MW:156.10 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Statistical Framework for Disease Association

The NAIR pipeline incorporates a novel statistical approach for identifying disease-associated clusters:

- Bayesian Integration: A new metric incorporating both generation probability (pgen) and clonal abundance using Bayes factor to filter false positives

- Generation Probability: Evaluation of which amino acid sequences are likely to be generated through V(D)J recombination, helping distinguish antigen-driven clonotypes from predetermined clones

- Abundance Adjustment: Integration of clonal frequency to identify statistically significant disease associations while controlling for generation likelihood [7]

Disease-Associated Cluster Identification Workflow

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The principles of reproducibility, robustness, and redundancy in immune repertoire architecture have significant implications for drug development and therapeutic design:

Vaccine Development: Understanding the reproducible aspects of repertoire architecture across individuals informs rational vaccine design aimed at eliciting robust, public responses that provide broad protection. The identification of public clones that serve as critical network hubs suggests these should be prioritized targets for vaccine-induced responses [7].

Immunotherapy Optimization: For cancer immunotherapy, assessing the robustness of T-cell repertoire architecture during treatment may predict therapeutic success and identify potential resistance mechanisms. Monitoring changes in network architecture could serve as a biomarker for treatment efficacy [7].

Biomarker Discovery: The redundancy principle guides the identification of disease-associated TCR/BCR clusters rather than individual sequences, potentially leading to more reliable diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers that account for the degenerate nature of antigen recognition [7].

Therapeutic Antibody Development: For antibody-based therapeutics, understanding the natural architecture of antibody repertoires informs engineering strategies that mimic natural structural principles, potentially leading to more effective and durable treatments [11].

The integration of network-based analysis of immune repertoires into therapeutic development pipelines represents a promising approach for advancing precision immunology and creating more effective interventions for infectious diseases, cancer, and autoimmune disorders.

The adaptive immune system recognizes a vast array of pathogens through an immense diversity of T-cell receptors (TCRs) and B-cell receptors (BCRs). The collection of these receptors within an individual constitutes the immune repertoire, which is highly dynamic and evolves across several orders of magnitude in size, physical location, and time [20]. Advances in Adaptive Immune Receptor Repertoire Sequencing (AIRR-seq) have enabled deep profiling of this complexity, generating large-scale datasets that require sophisticated computational approaches for interpretation [20]. Network analysis has emerged as a powerful framework for resolving the high-dimensional complexity of immune repertoires by representing sequence similarity relationships, thereby revealing the underlying architecture that governs immune recognition and response [7] [11].

This technical guide details the core concepts of representing immune repertoires as networks, focusing on the critical elements of nodes, edges, and similarity layers. This approach captures frequency-independent clonal sequence similarity relations, adding a complementary layer of information to traditional diversity analysis [7]. The sequence similarity architecture directly influences antigen recognition breadth, as more dissimilar receptors cover a larger antigen space [7]. We provide comprehensive methodologies, quantitative frameworks, and visualization strategies to empower researchers in implementing these approaches for characterizing immune repertoire architecture in health and disease.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Core Network Components

In immune repertoire networks, the fundamental building blocks transform raw sequence data into structured relational maps that capture biological meaningful relationships:

Nodes: Each node represents a unique immune receptor clonal sequence, typically defined by 100% complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) amino acid or nucleotide identity [11]. The CDR3 region is the most diverse part of the receptor and primarily dictates antigen specificity. Nodes can be weighted by clonal abundance (number of sequencing reads) or other properties.

Edges: Edges connect pairs of nodes based on sequence similarity, creating a similarity landscape of the immune repertoire [11]. Connections are established when the distance between sequences meets a predefined threshold. The resulting network is typically undirected and unweighted in its basic form.

Similarity Layers: Similarity layers, also referred to as distance thresholds, define the specific degree of sequence similarity required for edge creation [11]. These are constructed as Boolean undirected networks where nodes are connected if and only if they have a specific Levenshtein distance (e.g., LD1 for distance=1, LD2 for distance=2). Multiple similarity layers can be analyzed to understand repertoire architecture at different resolution levels.

Sequence Similarity Metrics

The calculation of sequence similarity is fundamental to edge formation in repertoire networks. The most commonly applied metrics include:

Levenshtein Distance (Edit Distance): Measures the minimum number of single-character edits (insertions, deletions, or substitutions) required to change one sequence into another [11]. This approach accommodates sequences of varying lengths without requiring stratification.

Hamming Distance: Calculates the number of positions at which corresponding characters differ between two equal-length sequences [7]. This metric is computationally efficient but requires sequences of identical length.

The selection of similarity threshold establishes the resolution of the network analysis, with lower thresholds (LD1) capturing closely related sequences and higher thresholds enabling connection of more distantly related sequences.

Quantitative Framework for Repertoire Network Architecture

Global Network Properties

Global network measures quantify the overall architecture of an entire immune repertoire, providing system-level insights into repertoire organization and connectivity:

Table 1: Key Global Network Properties for Characterizing Repertoire Architecture

| Network Property | Biological Interpretation | Measurement Approach | Representative Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Edges (E) | Overall clonal interconnectedness within repertoire | Total count of connections between nodes | pBC: 230,395 ± 23,048; nBC: 1,016,928 ± 67,080; PC: 45 ± 10 [11] |

| Size of Largest Component | Degree of repertoire connectivity | Percentage of nodes connected in the largest network component | pBC: 46 ± 0.7%; nBC: 58 ± 0.5%; PC: 10 ± 1.6% [11] |

| Average Degree (k) | Typical number of similar neighbors per clone | Average number of connections per node | pBC: 3; nBC: 5; PC: 1 [11] |

| Network Density (D) | Sparsity or density of similarity relationships | Ratio of existing edges to possible edges | PC: 0.01; pBC, nBC: ≈0 [11] |

| Network Centralization | Concentration of connectivity around central nodes | Degree to which network revolves around key nodes | PC: 0.05; pBC, nBC: ≈0 [11] |

Analysis of these global properties across B-cell development stages reveals fundamental architectural shifts: early B-cell stages (pre-B cells/naïve B cells) exhibit more continuous sequence space architecture, while antigen-experienced cells (memory plasma cells) display more fragmented and heterogeneous organization with concentrated centrality [11].

Local Network Properties

Local network measures focus on individual nodes and their immediate neighborhoods, providing insights into clonal-level properties and their potential functional implications:

Table 2: Local Network Properties for Clonal-Level Analysis

| Property | Definition | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Degree | Number of connections a node has | Indicates how many similar clones exist in repertoire |

| Betweenness Centrality | Number of shortest paths passing through a node | Identifies clones that bridge different sequence communities |

| Clustering Coefficient | Degree to which a node's neighbors connect to each other | Measures local connectivity density around specific clones |

| Eigenvector Centrality | Influence of a node based on its connections' importance | Identifies clones within well-connected regions of sequence space |

Clones with high betweenness centrality may function as critical connectors between different antigen specificity regions, while those with high eigenvector centrality reside within densely connected regions potentially representing public or convergent responses.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

NAIR Pipeline for TCR Repertoire Analysis

The Network Analysis of Immune Repertoire (NAIR) pipeline provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing TCR sequence data, with specific methodologies for identifying disease-associated clusters:

Network Construction and Initial Cluster Identification

The NAIR pipeline begins with TCR sequencing data from bulk AIRR-seq experiments [7]. For the European COVID-19 dataset used in the original study, this included 19 recovered subjects, 18 severely symptomatic subjects with active infection, and 39 age-matched healthy donors, totaling 108 samples with 901,045 unique TCRs [7]:

Sequence Preprocessing: Annotate TCR locus rearrangements using the MiXCR framework (version 3.0.13). Apply filters to remove non-productive reads and sequences with fewer than two read counts [7].

Distance Calculation: Compute the pairwise distance matrix of TCR amino acid sequences for each subject using Hamming distance (Python SciPy pdist function) [7].

Network Formation: Construct networks by connecting TCR sequences (nodes) with edges when their Hamming distance is less than or equal to 1 [7]. This creates the base similarity layer for subsequent analysis.

Identification of Disease-Associated Clusters

The NAIR methodology includes customized search algorithms to identify disease-associated TCR clusters [7]:

TCR Sharing Analysis: Determine the number of samples that share each TCR sequence.

Disease Association Testing: Apply Fisher's exact test (p < 0.05) to identify TCRs that appear more frequently in disease subjects compared to healthy controls. Retain only TCRs shared by at least 10 samples and with sequence length ≥ 6 amino acids [7].

Cluster Expansion: For each disease-associated TCR, identify all TCRs within the same cluster by searching among all TCRs from shared samples using network analysis (Hamming distance ≤ 1). Define clusters containing only disease samples as "disease-only TCR clusters" and others as "disease-associated TCR clusters" [7].

Global Membership Assignment: Generate a comprehensive network across all disease-associated TCRs, including their member TCRs within the same cluster, and assign global membership to the disease-associated clusters [7].

Large-Scale Antibody Repertoire Network Analysis

The architectural principles of antibody repertoires were revealed through large-scale network analysis of comprehensive human and murine datasets:

Computational Platform for Large-Scale Networks

Conventional network visualization approaches are limited to hundreds of nodes, while natural antibody repertoires exceed this by at least three orders of magnitude [11]. The implemented solution includes:

Distributed Computing Framework: Utilize Apache Spark distributed computing framework to partition computations across a cluster of machines, enabling analysis of >10^6 CDR3 amino acid sequences [11].

Distance Metric Selection: Calculate pairwise amino acid sequence similarity using Levenshtein distance, which accommodates sequences of arbitrary length without stratification [11].

Similarity Layer Construction: Build Boolean undirected networks (similarity layers) where nodes are connected if and only if they have a specific Levenshtein distance (e.g., LD1 for distance=1, LD2 for distance=2, up to LD12) [11].

Biological Validation Across B-Cell Development

The computational platform was applied to comprehensive antibody repertoire data to assess architecture across key biological parameters [11]:

Cross-Species Analysis: Compare human and murine antibody repertoires to identify conserved architectural principles.

B-Cell Developmental Stages: Analyze pre-B cells, naïve B cells, and memory plasma cells to understand architectural changes during B-cell maturation.

Antigen Experience Comparison: Contrast architecture before (pre-B cells, naïve B cells) and after (memory plasma cells) antigen-driven clonal selection and expansion.

Antigen Complexity: Examine repertoire responses to antigens of varying complexity (HBsAg, OVA, NP-HEL).

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Immune Repertoire Network Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAIR Pipeline | Computational Method | Network analysis of TCR repertoire with disease association testing | Identifying COVID-19-specific TCRs [7] |

| Apache Spark Framework | Distributed Computing Platform | Enables large-scale network construction (>10^6 nodes) | Analyzing comprehensive antibody repertoires [11] |

| MiXCR | Bioinformatics Tool | Annotation of TCR/BCR repertoire sequencing data | Preprocessing of TCR-seq data before network analysis [7] |

| GLIPH2 | Computational Algorithm | Clusters TCR sequences based on sequence similarity | Identifying potential targets for immunotherapeutic interventions [7] |

| ImmunoMap | Computational Algorithm | Identifies antigen specificities using known antigen database | Mapping TCR sequences to antigen targets [7] |

| MIRA Database | Reference Database | Contains high-confidence antigen-specific TCRs | Validation of disease-specific TCRs [7] |

| CellChat | R Package | Cell-cell communication analysis from scRNA-seq data | Inferring signaling networks between cell types [21] |

| IgDiscover | Bioinformatics Tool | De novo germline gene database reconstruction | Personalized VDJ reference database creation [20] |

Fundamental Principles of Repertoire Architecture

Network analysis of immune repertoires has revealed three fundamental principles that define repertoire architecture across individuals and species:

Reproducibility: Antibody repertoire networks show remarkable cross-individual consistency in global network measures despite high antibody sequence dissimilarity between individuals [11]. The number of edges, size of largest component, and cluster composition vary negligibly across individuals, suggesting that VDJ recombination generates antibody repertoires with convergent architecture.

Robustness: The architecture of antibody repertoires demonstrates unexpected robustness to the random removal of clones (remaining stable with removal of 50-90% of randomly selected clones) but exhibits fragility to the targeted removal of public clones shared among individuals [11]. This indicates that public clones serve as critical hubs maintaining repertoire connectivity.

Redundancy: Repertoire architecture is intrinsically redundant, with multiple clones occupying similar sequence neighborhoods, ensuring functional resilience against pathogen evasion and stochastic clone loss [11]. This redundancy provides a buffer that maintains repertoire coverage despite constant cellular turnover.

These principles establish a quantitative framework for understanding how repertoire architecture supports robust immune function despite enormous sequence diversity and constant cellular dynamics.

Advanced Analytical Framework

Incorporating Generation Probability and Abundance

The NAIR pipeline introduces advanced statistical approaches to distinguish antigen-driven responses from genetically predetermined clones:

Generation Probability (pgen): Calculate the probability that a specific amino acid sequence would be generated through VDJ recombination processes, with higher probability sequences more likely to appear in any individual without antigen-specific selection [7].

Bayes Factor Integration: Incorporate both generation probability and clonal abundance using Bayes factors to evaluate the importance of clones and filter out false positives in disease-specific TCR identification [7].

Public Clone Analysis: Identify clones shared across individuals or within an individual across time, which are enriched for MHC-diverse CDR3 sequences associated with autoimmune, allograft, tumor-related, and anti-pathogen responses [7].

Cross-Platform Validation Strategies

Robust validation of identified disease-associated clusters requires multiple orthogonal approaches:

Independent Cohort Validation: Apply identified TCR clusters to independent patient cohorts to verify disease association and specificity.

Antigen-Specific Database Mapping: Validate findings against established antigen-specific TCR databases such as the Adaptive MIRA database, which contains over 135,000 high-confidence SARS-CoV-2-specific TCRs [7].

Functional Validation: Correlate computational findings with clinical outcomes such as disease severity, recovery trajectory, or treatment response to establish biological relevance [7].

Network analysis using nodes, edges, and similarity layers provides a powerful quantitative framework for characterizing the architecture of immune repertoires. The methodologies detailed in this guide enable researchers to move beyond diversity metrics alone to capture the similarity relationships that define functional immune capacity. The reproducible, robust, and redundant principles underlying repertoire architecture revealed through these approaches offer new insights for developing immunotherapeutics, vaccines, and diagnostics. As AIRR-seq technologies continue to evolve, network-based analytical frameworks will play an increasingly critical role in translating immune repertoire data into biological understanding and clinical applications.

From Data to Discovery: Methodological Frameworks and Applications

In the field of immunology, understanding the architecture and dynamics of immune repertoires is crucial for unraveling the complexities of disease response, therapeutic development, and immune system function. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized this domain by enabling comprehensive profiling of T-cell and B-cell receptor sequences [22]. The choice of sequencing strategy—bulk versus single-cell, and DNA versus RNA templates—fundamentally shapes the type and quality of architectural insights that can be gained from repertoire network analysis. This technical guide examines these core sequencing methodologies within the context of immune repertoire research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a structured framework for experimental design and implementation.

Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Technical Comparison

Fundamental Methodological Differences

Bulk RNA sequencing provides a population-average gene expression profile by extracting RNA from an entire tissue or cell population. The resulting data represents a composite of gene expression patterns across all cells in the sample, yielding an averaged transcriptional signature without cellular resolution [23] [24]. This approach is particularly valuable for obtaining a holistic view of transcriptional states and identifying dominant expression patterns across cell populations.

In contrast, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) captures the gene expression profile of each individual cell within a heterogeneous sample. Technologies like the 10x Genomics Chromium system achieve this by partitioning single cells into nanoliter-scale reactions (Gel Beads-in-emulsion, or GEMs) where each cell's RNA is barcoded with a unique cellular identifier before library preparation and sequencing [23] [24]. This approach preserves the identity of each cell's transcriptome, enabling the resolution of cellular heterogeneity and the identification of rare cell populations.

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

The experimental workflow for bulk RNA-seq involves digesting the biological sample to extract total RNA or enriched mRNA, followed by conversion to cDNA and preparation of a sequencing-ready gene expression library [23]. This relatively straightforward protocol requires minimal specialized equipment beyond standard molecular biology tools and NGS library preparation systems.

Single-cell RNA sequencing demands more complex sample preparation, beginning with the generation of viable single-cell suspensions through enzymatic or mechanical dissociation of tissues [23] [24]. Critical quality control steps ensure appropriate cell concentration, viability, and absence of clumps or debris. The partitioned cells undergo lysis within GEMs, where released RNA is barcoded with cell-specific identifiers. The barcoded products are then used to construct sequencing libraries that maintain cellular origin information throughout the process [23].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

| Parameter | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average | Individual cell level |

| Sample Input | Pooled cell population | Single-cell suspension |