Decoding Immune Variation: How Genetics and Environment Shape Human Health and Disease Treatment

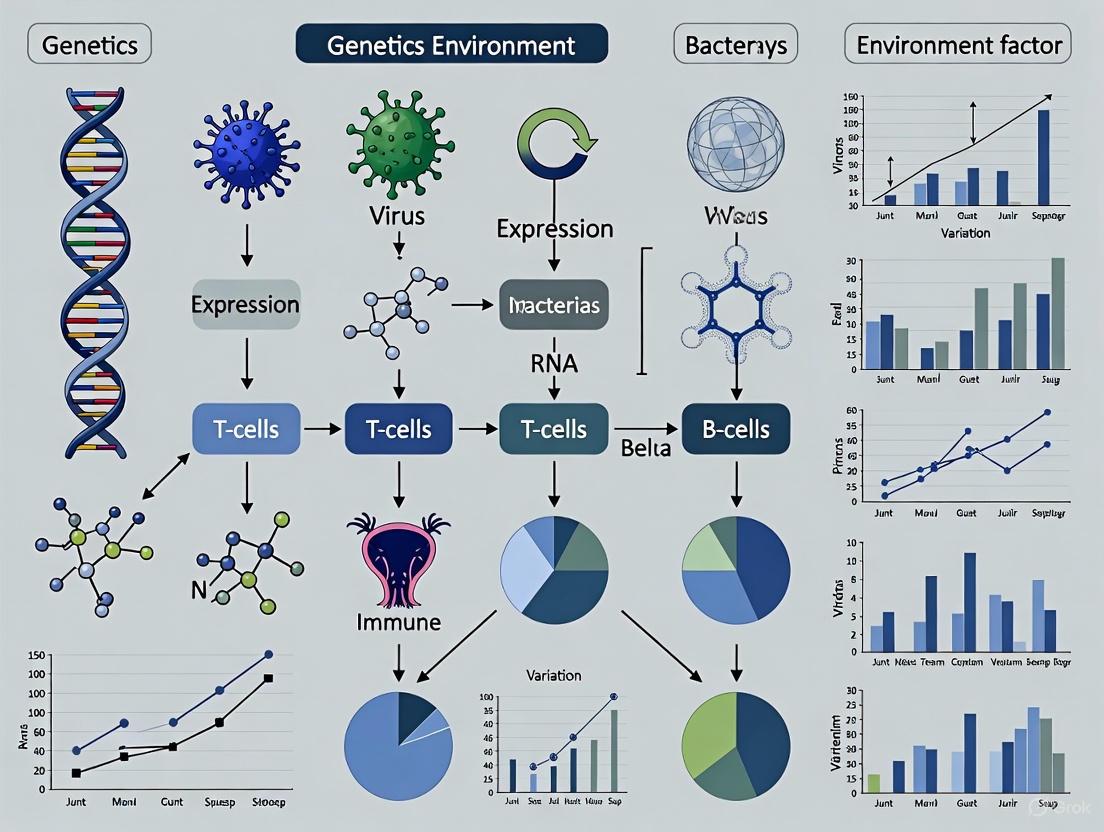

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the complex interplay between genetic susceptibility and environmental factors in shaping inter-individual immune variation.

Decoding Immune Variation: How Genetics and Environment Shape Human Health and Disease Treatment

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the complex interplay between genetic susceptibility and environmental factors in shaping inter-individual immune variation. We explore foundational concepts of immune system heterogeneity, examine cutting-edge methodological approaches like GWAS and Mendelian randomization for target discovery, and address key challenges in translating these insights into effective therapies. The content further validates these strategies through case studies in autoimmune diseases and infectious diseases like COVID-19, highlighting how genetic evidence de-risks drug development and informs personalized treatment paradigms. By synthesizing recent advances in multi-omics and systems immunology, this review serves as a strategic guide for leveraging human genetic variation to improve therapeutic outcomes.

The Blueprint and the Trigger: Foundational Principles of Genetic Susceptibility and Environmental Exposures

The human immune system is a complex network of cells and proteins that defends the body against infection. Understanding the genetic blueprint that controls the immense variation in immune responses between individuals is a fundamental pursuit in immunology and precision medicine. This variation arises from a complex interplay between inherited genetic factors and environmental exposures throughout life. The Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC), particularly the Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) genes, represents the most critical genetic locus governing immune recognition. However, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have increasingly revealed the significant contribution of non-HLA risk loci outside this region. This technical review synthesizes current knowledge on the genetic architecture of immune variation, framing it within the broader context of how genetics and environment interact to shape individual immune phenotypes. We provide a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, integrating recent genomic discoveries with experimental methodologies and analytical frameworks.

The MHC Region: Central Command for Immune Recognition

Structural and Functional Organization of the MHC

The MHC region on chromosome 6p21.3 spans approximately 4 Mb and is characterized by extreme polymorphism, high gene density, and strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) [1]. This region is traditionally divided into three classes:

- Class I genes (HLA-A, -B, -C): Present intracellular peptides to CD8+ T-cells; expressed on most nucleated cells.

- Class II genes (HLA-DR, -DQ, -DP): Present extracellular peptides to CD4+ T-cells; primarily expressed on antigen-presenting cells.

- Class III genes: Encode complement components and inflammatory cytokines.

The classical HLA genes are among the most polymorphic in the human genome, with the IPD-IMGT/HLA Database documenting over 10,000 alleles for HLA-B alone [2]. This diversity primarily localizes to the antigen-binding groove, enabling recognition of a vast array of pathogens.

Table 1: Key Features of the MHC Genomic Region

| Feature | Description | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Size | ~4 Mb on chromosome 6p21.3 | Dense clustering of immunologically relevant genes |

| Gene Content | >250 genes, including classical HLA genes (A, B, C, DR, DQ, DP) and non-classical genes (E, G, etc.) | Coordinated regulation of innate and adaptive immunity |

| Polymorphism | Extreme diversity with trans-species polymorphisms | Recognition of diverse pathogen repertoire; balancing selection |

| Linkage Disequilibrium | Extensive and complex LD patterns | Challenges in pinpointing causal variants; haplotype blocks |

| Expression Variation | Allele-specific expression and alternative splicing | Additional layer of regulatory complexity beyond protein coding |

Mechanistic Insights from MHC-Disease Associations

GWAS have established that the MHC region shows the strongest genetic associations for numerous autoimmune, infectious, and inflammatory diseases [3] [1]. The mechanistic underpinnings of these associations are multifaceted:

- Peptide Presentation Specificity: Certain HLA types confer risk by preferentially presenting self-antigens (in autoimmunity) or inefficiently presenting pathogen-derived antigens (in infectious disease) [1].

- Expression Level Variation: HLA types are associated with differential expression of their cognate genes, potentially influencing immune activation thresholds. A study of 361 iPSC lines found that 44.2% of HLA types showed significantly different expression levels compared to other alleles of the same gene [1].

- Regulatory Variation: Non-coding variants can alter gene expression through effects on transcription factor binding, as demonstrated by histone QTLs enriched within autoimmune risk haplotypes [4].

- Ancestral Haplotypes: Extended haplotypes spanning the entire MHC region, such as the 8.1 ancestral haplotype (8.1AH), carry multiple risk alleles and are associated with multiple autoimmune diseases while being protective against bacterial colonization in cystic fibrosis patients [1].

Non-HLA Risk Loci: Expanding the Genetic Landscape

Genome-Wide Insights into Immune Regulation

While the MHC region accounts for a substantial portion of heritability for immune-mediated diseases, GWAS have identified hundreds of non-HLA risk loci distributed across the genome. These loci typically confer more modest individual risk effects but collectively contribute significantly to disease susceptibility. Systematic evaluations reveal that these non-HLA loci are frequently enriched in immune cell enhancers and regions of open chromatin, highlighting their likely regulatory functions [5].

In primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), a systematic review of 105 studies involving 71,031 cases and 140,499 controls identified 44 variants significantly associated with disease risk, comprising 30 HLA variants and 14 non-HLA variants [5]. Pathway analysis revealed significant enrichment of mapped genes in immune cell regulation and immune response-regulating signaling pathways.

Functional Annotation of Non-HLA Variants

The majority of disease-associated non-HLA variants reside in non-coding genomic regions, suggesting they exert their effects through gene regulation rather than protein coding changes [4]. Several mechanisms have been elucidated:

- Cis-Regulatory Effects: Non-coding variants can alter transcription factor binding affinity, affecting gene expression levels. For example, an obesity-associated variant in the FTO locus alters ARID5B binding, leading to increased expression of IRX3 and IRX5 genes [4].

- Post-Transcriptional Regulation: Variants can affect RNA splicing, stability, or translation through alteration of miRNA binding sites or RNA-binding protein interactions [4].

- Epigenetic Modulation: Genetic variants can influence chromatin accessibility and histone modifications, creating cell-type-specific regulatory landscapes.

Table 2: Representative Non-HLA Immune Risk Loci and Their Proposed Mechanisms

| Locus/Gene | Associated Disease(s) | Variant(s) | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTPN22 | Rheumatoid arthritis, Type 1 diabetes, SLE | rs2476601 | Gain-of-function mutation weakening T-cell receptor signaling |

| IL23R | Inflammatory bowel disease, Psoriasis | rs11209026 | Altered IL-23 signaling affecting Th17 cell differentiation |

| NOD2 | Crohn's disease | rs2066844, rs2066845, rs2066847 | Impaired recognition of bacterial peptidoglycan |

| IRF5 | Systemic lupus erythematosus | rs10488631 | Increased expression of type I interferon-regulated genes |

| TNFAIP3 | Rheumatoid arthritis, SLE | rs10499194, rs6920220 | Impaired negative regulation of NF-κB signaling |

Quantitative Assessment of Genetic Contributions

Heritability Estimates and Locus Effect Sizes

The relative contribution of genetic factors to immune traits and diseases varies considerably. Twin studies provide estimates of broad-sense heritability, while GWAS-derived significant SNPs account for narrow-sense heritability. For example, monozygotic twin concordance rates for Crohn's disease approach ~50% compared to ~3-4% in dizygotic twins, indicating a substantial genetic component [4].

Recent analyses of FinnGen data (412,181 individuals, 2,459 diseases) demonstrate striking enrichment of disease associations in the HLA region compared to the rest of the genome [3]. Infectious diseases showed nearly 400-fold enrichment in the HLA region, while autoimmune, endocrine, and dermatologic diseases showed 100- to 200-fold enrichment [3].

Pleiotropy and Risk Trade-Offs in the HLA Region

The HLA region exhibits extensive pleiotropy, where specific genetic variants influence multiple distinct diseases. Haplotype-based analyses have revealed complex patterns of disease associations, with some HLA alleles conferring risk for certain conditions while being protective against others [3]. This pleiotropy reflects evolutionary trade-offs, wherein alleles that enhance protection against specific pathogens may simultaneously increase susceptibility to autoimmune or inflammatory disorders.

Table 3: Venice Criteria Assessment of Genetic Associations in Primary Biliary Cholangitis [5]

| Variant/Gene | Pooled OR (95% CI) | P-value | Cumulative Evidence | False-Positive Report Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-DQB1*0301 | 1.42 (1.28-1.57) | < 5.0 × 10⁻⁸ | Strong | < 0.05 |

| HLA-DRB1*08 | 2.98 (2.58-3.44) | < 5.0 × 10⁻⁸ | Strong | < 0.05 |

| rs231775 (CTLA-4) | 1.32 (1.24-1.41) | < 5.0 × 10⁻⁸ | Strong | < 0.05 |

| rs7574865 (STAT4) | 1.43 (1.34-1.52) | < 5.0 × 10⁻⁸ | Strong | < 0.05 |

| A*3303 | 2.15 (1.72-2.69) | < 5.0 × 10⁻⁸ | Strong | < 0.05 |

Gene-Environment Interactions: Shaping Immune Phenotypes

Experimental Models for G×E Interactions

The relative contributions of genetic and environmental factors to immune variation remain incompletely characterized. Controlled experiments with "rewilded" laboratory mice—inbred strains introduced into natural outdoor environments—have provided key insights [6]. When C57BL/6, 129S1, and PWK/PhJ mice were rewilded and infected with Trichuris muris, multivariate analysis revealed that:

- Cellular composition of peripheral blood mononuclear cells was shaped by interactions between genotype and environment (Gen × Env)

- Cytokine response heterogeneity was primarily driven by genotype, with consequences for parasite burden

- Genetic differences observed under laboratory conditions were often reduced following rewilding [6]

These findings demonstrate that nonheritable influences interact with genetic factors to shape immune variation and disease outcomes.

Molecular Signatures of G×E Interactions

Human studies have mapped genetic variants that affect how gene expression changes in response to immune stimulation. Monocytes from 134 volunteers treated with pathogen-mimicking components revealed hundreds of genes where response to immune stimulus depended on the individual's genetic variants [7]. This research demonstrated that:

- Genetic risk for autoimmune diseases like lupus and celiac disease is enriched for gene regulatory effects modified by immune activation state

- Genetic risk factors may sometimes manifest only under specific environmental conditions, such as infection [7]

- A complete understanding of disease risk requires consideration of both genetic makeup and environmental exposures

Methodologies: Decoding Immune Variation

Analytical Frameworks and Computational Tools

MHC Hammer: Comprehensive HLA Disruption Analysis

MHC Hammer is a computational toolkit that evaluates genomic and transcriptomic disruption of class I HLA genes through four major components [8]:

- Allele-specific HLA somatic mutation identification

- HLA loss of heterozygosity (LOH) calculation

- HLA allele-specific repression evaluation

- Allele-specific HLA alternative splicing identification

Application to normal lung and breast tissue from the GTEx project revealed pervasive HLA allelic imbalance (70-81% of samples across HLA genes) and frequent alternative splicing (87-97% of samples) [8]. These findings emphasize the importance of controlling for baseline HLA expression variation when assessing transcriptional alterations in disease.

MHC Hammer Analysis Workflow: A comprehensive pipeline for evaluating HLA genomic and transcriptomic disruption.

Haplotype-Based Association Mapping

To address the challenges of extreme linkage disequilibrium in the HLA region, haplotype-based approaches have been developed that consider combinations of variants across extended genomic segments. These methods have revealed that:

- Disease associations often track with specific haplotypes rather than individual SNPs

- Regulatory variation can confer disease risk independently of classical HLA coding variation

- Analysis of phased haplotypes provides enhanced power to detect associations compared to single-variant approaches [3] [1]

Experimental Protocols for Immune Repertoire Profiling

Multimodal Single-Cell Profiling of Tissue Immunity

Comprehensive analysis of immune cells across tissues requires specialized methodologies [9]:

Protocol: Multimodal Immune Cell Profiling from Human Tissues

Tissue Acquisition and Processing

- Source tissues from organ donors within 4-8 hours of cross-clamp time

- Process tissues using mechanical dissociation and enzymatic digestion (e.g., collagenase IV/DNase I)

- Isolate mononuclear cells via density gradient centrifugation

Cell Staining and Sorting

- Stain cells with antibody panels for surface markers (≥125 antibodies for CITE-seq)

- Include viability dyes to exclude dead cells

- Sort specific populations if needed using FACS

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Generate single-cell suspensions for 10x Genomics platform

- Prepare gene expression libraries alongside feature barcodes for surface proteins

- Sequence on Illumina platforms with sufficient depth (≥20,000 reads/cell)

Bioinformatic Analysis

- Process data using Cell Ranger with custom reference incorporating HLA alleles

- Integrate datasets across donors using harmony or similar tools

- Annotate cell types leveraging both RNA and protein expression (e.g., with MMoCHi)

- Perform differential expression and trajectory analysis

This approach has revealed tissue-directed signatures of human immune cells altered with age, showing that age-associated effects manifest in a tissue- and lineage-specific manner [9].

Rewilding Experimental Design

The rewilding approach models human environmental exposures in genetically defined mouse strains [6]:

Protocol: Rewilding and Immune Challenge

Animal Housing and Group Assignment

- Use 8-12 week old female inbred mice (C57BL/6, 129S1, PWK/PhJ)

- Randomly assign to laboratory housing ("Lab") or outdoor enclosures ("Rewilded")

- Maintain laboratory controls under summer-like photoperiod and temperature

Environmental Exposure and Infection

- Acclimate rewilded mice for 2 weeks in outdoor enclosures

- Infect with 200 Trichuris muris embryonated eggs or leave uninfected

- Return to respective environments for additional 3 weeks

Sample Collection and Analysis

- Collect peripheral blood at multiple time points for CBC/DIFF and PBMC isolation

- Process tissues (spleen, lymph nodes, intestinal sections) for cellular analysis

- Analyze by spectral cytometry with comprehensive lymphocyte and myeloid panels

- Perform multivariate statistical analysis (MDMR) to partition variance components

Rewilding Experimental Design: Approach to quantify genetic and environmental contributions to immune variation.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Immune Variation Studies

| Resource | Type | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| MHC Hammer | Computational pipeline | HLA disruption analysis | Integrates genomic and transcriptomic data; detects LOH, allele-specific expression, and splicing [8] |

| HLA-VBSeq | Computational tool | Eight-digit HLA typing from WGS | High recall rates (>98.5%) and reproducibility (>95%) across 30 MHC genes [1] |

| CITE-seq | Experimental platform | Multimodal single-cell profiling | Simultaneous measurement of transcriptome and >125 surface proteins [9] |

| MMoCHi | Computational classifier | Cell type annotation | Leverages both surface protein and gene expression for hierarchical classification [9] |

| Rewilding Enclosures | Experimental system | Gene-environment interactions | Naturalistic outdoor environments for laboratory mice [6] |

| MARIO | Computational method | Allele-specific binding | Identifies regulatory protein binding differences at heterozygous variants [4] |

The genetic architecture of immune variation represents a complex, multi-layered system centered on the highly polymorphic MHC region but extending to numerous non-HLA loci distributed throughout the genome. The functional consequences of this genetic variation are expressed through allele-specific expression, alternative splicing, regulatory element modulation, and protein coding changes that collectively shape immune responsiveness. Critically, these genetic effects do not operate in isolation but interact dynamically with environmental exposures throughout life, as demonstrated by rewilding experiments and studies of immune activation. Future research must continue to develop increasingly sophisticated analytical frameworks that can dissect these complex relationships, with particular attention to underrepresented populations and tissue-specific effects. The integration of genetic data with functional genomics and environmental context will be essential for translating these insights into targeted therapeutic strategies and personalized medicine approaches for immune-mediated diseases.

The immune system is not a static entity but a dynamic interface, continuously shaped by the complex interplay between an individual's genetic blueprint and their lifetime exposure to environmental factors. While genetic predisposition sets the foundational rules of immune responsiveness, a growing body of evidence indicates that nonheritable influences interact with these genetic factors to orchestrate immune variation and disease susceptibility [6]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of key environmental triggers and modulators—infections, the microbiome, and pollutants—framed within the context of immune variation research. Understanding these interactions is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to deconvolute disease etiology and develop targeted therapeutic interventions.

The Genotype-Environment Interface in Immune Variation

Quantifying the relative contributions of genetics and environment is methodologically challenging. Studies often attribute variation not linked to genetics to "environment" alone, overlooking critical genotype-by-environment (Gen × Env) interactions, which occur when environmental effects are differentially amplified in different genetic backgrounds [6]. Controlled experiments using inbred mouse strains of diverse genetic backgrounds (e.g., C57BL/6, 129S1, and the wild-derived PWK/PhJ) have been instrumental in dissecting these interactions.

A pivotal "rewilding" study introduced laboratory mice to a natural outdoor environment, exposing them to a complex array of natural antigens and microbes. Subsequent analysis demonstrated that cellular composition of immune cells was significantly shaped by Gen × Env interactions. In contrast, cytokine response heterogeneity, such as IFNγ production, was primarily driven by genotype, with direct consequences on pathogen burden, as shown by infection with the helminth Trichuris muris [6]. Notably, some genetic differences in immune markers (e.g., CD44 expression on T cells) observed under controlled laboratory conditions were diminished following rewilding, while other differences (e.g., a stronger T helper 1 response to infection in C57BL/6 mice) emerged only in the rewilding condition [6]. This underscores that the effect of an extreme environmental shift on immune phenotype is modulated by genetics, and, in turn, the expressivity of genetic differences among strains is modulated by the environment.

Table 1: Relative Contributions of Genetics and Environment to Specific Immune Traits in a Rewilding Model

| Immune Trait | Genetic Influence | Environmental Influence | Gen × Env Interaction | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBMC Cellular Composition | Significant | Significant | Notable Contributor | Multivariate analysis of rewilded vs. lab mice [6] |

| IFNγ Cytokine Response | Primary Driver | Lesser Contribution | Not Reported | Infection with Trichuris muris [6] |

| CD44 Expression on T cells | Mostly Explained | Lesser Contribution | Not Reported | Comparison across strains and environments [6] |

| CD44 Expression on B cells | Lesser Contribution | Mostly Explained | Not Reported | Comparison across strains and environments [6] |

| TH1 Response to T. muris | Dependent on Environment | Dependent on Genotype | Emergent | Stronger response in C57BL/6 mice only in rewilding [6] |

Environmental Pollutants as Immunomodulators

Environmental pollutants represent a significant class of immunomodulatory triggers, with exposure linked to a range of inflammatory, autoimmune, and metabolic pathologies. These pollutants can exert their effects directly on immune cells or indirectly through the disruption of the gut microbiome.

Mechanisms of Pollutant-Induced Immunotoxicity

Pollutants, including heavy metals, persistent organic pollutants (POPs), and particulate matter (PM), can perturb the immune system through several direct and indirect mechanisms:

- Direct Immune Activation: Air pollutants like PM2.5 are taken up by lung immune cells, triggering the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) that drive systemic inflammation and oxidative stress [10]. Heavy metals such as lead can dysregulate inflammatory enzymes and promote ROS production, disrupting cell membranes via lipid peroxidation [10].

- Microbiome-Mediated Effects: Upon ingestion, pollutants interact with the gut microbiome, the first line of contact for many ingested xenobiotics. Gut microbes can metabolize pollutants into more or less toxic states, influencing their systemic distribution [11]. Conversely, pollutants can cause gut dysbiosis, characterized by a decrease in beneficial commensal bacteria (e.g., short-chain fatty acid producers) and an overgrowth of pro-inflammatory species [12] [10]. This dysbiosis can compromise intestinal barrier integrity, leading to a "leaky gut" that allows bacterial metabolites and virulence factors (e.g., LPS) to enter the bloodstream, perpetuating systemic inflammation [12] [10].

- Epigenetic Modulation: Exposure to air pollutants has been associated with epigenetic modifications, such as the hypermethylation of the Foxp3 gene, which can weaken the function of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and disrupt immune tolerance [10].

Table 2: Immunotoxic Effects of Select Environmental Pollutants

| Pollutant Class | Example Compounds | Primary Exposure Route | Key Immunological Consequences | Proposed Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Metals | Lead (Pb), Cadmium (Cd), Mercury (Hg) | Ingestion, Inhalation | Oxidative stress, pro-inflammatory cytokine release, autoimmunity, gut dysbiosis [12] [10] | ROS generation, inflammation enzyme dysregulation, altered gut microbiota composition [11] |

| Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) | Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) | Ingestion | Altered gut microbial composition, inflammation [11] | Activation of signaling pathways (e.g., Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor/AHR) within the intestine [11] |

| Particulate Matter | PM2.5, PM10 | Inhalation | Exacerbation of asthma/COPD, increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis and IBD, systemic inflammation [10] | Uptake by lung immune cells, cytokine release, oxidative stress, impaired phagocytosis, Treg impairment [10] |

| Microplastics | Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | Ingestion | Gut inflammation, oxidative stress, systemic diseases [10] | Intestinal cell uptake, intracellular oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, activation of TLRs [10] |

The Gut Microbiome as a Central Signaling Hub

The gut microbiota, a complex ecosystem of trillions of microorganisms, is a critical intermediary between environmental exposures and host immunity. It plays a fundamental role in the maturation and regulation of the immune system, and its disruption is a common pathway through which other environmental triggers exert their effects.

The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis (MGBA)

The bidireсtionаl сommuniсаtion between the gut and the brain, known as the gut-brain axis (GBA), is heavily influenced by the microbiota. The MGBA involves communication through neurological (autonomous nervous system, vagus nerve), hormonal (HPA axis), and immunological (cytokine) pathways [12]. Gut microbes produce a vast array of metabolites that can signal to distant organs, including the brain.

- Key Microbial Metabolites:

- Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): Produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber, SCFAs like butyrate, propionate, and acetate are crucial for maintaining intestinal barrier integrity and have systemic anti-inflammatory effects. They can cross the blood-brain barrier via monocarboxylate transporters, where they modulate neuroinflammation, influence brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels, and support neurogenesis [12].

- Neuroactive and Immunomodulatory Metabolites: The microbiome influences tryptophan metabolism, a precursor for serotonin, and can produce or consume other neurotransmitters [12]. Changes in the availability of these metabolites can significantly impact brain function and behavior.

Metabolite-Immune Interactions Across Populations

Recent large-scale metabolomic studies have further illuminated the intricate links between circulating metabolites and immune function. A multi-cohort analysis of individuals from Western Europe and sub-Saharan Africa identified robust associations between specific metabolic pathways and cytokine responses.

- Glycerophospholipid Metabolism: This pathway was consistently identified across cohorts as being associated with cytokine production (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, TNF) following Staphylococcus aureus stimulation, highlighting its cross-population relevance in immune regulation [13].

- Sphingomyelin: This sphingolipid exhibited a significant negative correlation with monocyte-derived cytokine production. Functional validation experiments confirmed that sphingomyelin could reduce TNF, IL-1β, and IL-6 production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Furthermore, Mendelian randomization analysis established a causal link between higher sphingomyelin levels and increased COVID-19 severity, positioning it as a potential therapeutic target for immune modulation [13].

Table 3: Key Metabolites Linking Microbiome and Immune Function

| Metabolite | Origin | Associated Immune Function | Mechanistic Insight & Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) | Gut microbial fermentation of dietary fiber | Anti-inflammatory; maintenance of gut barrier; regulation of microglia & neuroinflammation [12] | Cross BBB; promote Treg differentiation; modulate neurotrophic factors [12] |

| Sphingomyelin | Host synthesis, dietary intake | Negative regulation of innate immune response; reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production (TNF, IL-6, IL-1β) [13] | Experimentally validated to inhibit cytokine production in PBMCs; MR shows causal link to COVID-19 severity [13] |

| Glycerophospholipids | Host synthesis, dietary intake | Correlation with cytokine responses (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF) to bacterial stimuli [13] | Pathway consistently enriched in immune-metabolite interaction networks across diverse cohorts [13] |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: Rewilding and Helminth Infection Model

This protocol is designed to quantify the interactive effects of genotype and environment on immune phenotypes and parasite burden [6].

Animal Models and Housing:

- Utilize genetically diverse inbred mouse strains (e.g., C57BL/6, 129S1, PWK/PhJ).

- Randomly assign mice into two environmental groups:

- Laboratory Controls: Housed in a conventional vivarium under standard or summer-mimicking photoperiod/temperature.

- Rewilded: Housed in a protected outdoor enclosure for a defined period (e.g., 2 weeks pre-infection).

Infection Challenge:

- After the initial environmental exposure (e.g., 2 weeks), infect a subset of mice from each group and environment with approximately 200 embryonated eggs of the intestinal helminth Trichuris muris. Maintain a separate uninfected control group for each condition.

- Return all mice to their respective environments (lab or outdoor) for a further 3 weeks.

Sample Collection and Analysis:

- Peripheral Blood: Collect blood at multiple time points for complete blood count (CBC) with differential and for PBMC isolation.

- Immune Phenotyping by Spectral Cytometry: Isolate PBMCs and stain with a comprehensive lymphocyte panel (e.g., including CD4, CD8, B220, TCRβ, CD44, Ki-67, T-bet). Use unsupervised k-means clustering to group cells into populations based on marker expression for unbiased analysis.

- Cytokine Analysis: Measure cytokine production (e.g., IFNγ) from stimulated immune cells or in serum.

- Worm Burden Assessment: At endpoint, quantify adult worms in the cecum/colon to determine parasite burden.

Statistical Analysis:

- Multivariate Distance Matrix Regression (MDMR): Use MDMR to quantify the independent and interactive contributions of genotype, environment, and infection to the high-dimensional variance in immune cell composition.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Visualize the major axes of variation in immune profiles and identify cell populations driving these patterns.

In Vitro Protocol: Metabolite-Mediated Immune Modulation

This protocol validates the immunomodulatory effect of specific metabolites identified in association studies [13].

Cell Isolation and Culture:

- Isolate human PBMCs from fresh whole blood of healthy donors by density gradient centrifugation (e.g., Ficoll-Paque).

- Resuspend PBMCs in appropriate culture medium (e.g., RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS).

Metabolite Treatment and Stimulation:

- Pre-treat PBMCs with the metabolite of interest (e.g., sphingomyelin, dissolved in a suitable vehicle) at a range of physiological concentrations. Include vehicle-only control wells.

- After pre-treatment (e.g., 1-2 hours), stimulate the cells with a potent innate immune activator, such as heat-killed Staphylococcus aureus. Maintain unstimulated controls.

Cytokine Measurement:

- After incubation (e.g., 24 hours for innate cytokines), collect cell culture supernatants.

- Quantify the concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF, IL-6, IL-1β) using high-sensitivity immunoassays (e.g., ELISA or multiplex bead-based arrays).

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

Pollutant-Induced Immunotoxicity Pathways

Diagram 1: Integrated pollutant-gut-immune axis.

Rewilding Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Rewilding experiment design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Resources for Investigating Environment-Immune Interactions

| Resource Category | Specific Example | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Models | C57BL/6, 129S1, PWK/PhJ inbred mice [6] | Provide controlled genetic diversity to model human population variation and study Gen × Env interactions. |

| Pathogen Challenge | Trichuris muris embryonated eggs [6] | Standardized parasite challenge to study mucosal and systemic immune responses in different environments. |

| Immunophenotyping | Spectral Cytometry Panel (TCRβ, B220, CD4, CD8, CD44, Ki-67, T-bet) [6] | High-dimensional, unbiased characterization of immune cell composition and activation states. |

| Data Resources | Immune Signatures Data Resource [14] | A compendium of standardized systems vaccinology datasets (30 studies, 1405 participants) for comparative analysis of vaccine-induced immune responses. |

| Analytical Tools | Multivariate Distance Matrix Regression (MDMR) [6] | Statistical method to quantify contributions of genotype, environment, and their interaction to high-dimensional immune variation. |

| Metabolite Libraries | Sphingomyelin, Short-Chain Fatty Acids [13] [12] | For functional validation experiments in vitro to test causal effects of metabolites on immune cell function. |

| Interactive Databases | IMetaboMap [13] | Publicly available tool for exploring metabolite-cytokine interactions across different ethnicities and sexes. |

The aetiology of complex human diseases has long been understood to extend beyond purely genetic or environmental explanations, residing instead in their dynamic interplay. This in-depth technical guide explores the Convergence Model, which posits that disease pathogenesis emerges from the interaction of an individual's genetic susceptibility with cumulative environmental exposures. Framed within the broader context of immune variation research, this review synthesizes current evidence on molecular mechanisms—with a focus on epigenetic regulation—and details advanced methodological frameworks for studying these interactions. We provide structured quantitative data, experimental protocols for key studies, and visualizations of critical signalling pathways to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the tools to advance this field. The translation of these findings promises to reshape therapeutic strategies towards precision environmental health and preventive medicine.

For decades, the quest to understand disease aetiology has oscillated between genetic determinism and environmental causation. The Convergence Model resolves this false dichotomy by proposing that genetic predisposition and environmental factors interact in a complex, non-additive manner to drive disease pathogenesis [15]. This framework is particularly relevant for immune-mediated diseases, where the immune system serves as a critical interface between an organism's genetic blueprint and its environmental exposures.

The limitations of studying these factors in isolation are increasingly apparent. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified hundreds of disease-associated genetic loci, yet these variants typically confer only modest increases in disease risk and often exhibit incomplete penetrance [15]. For example, in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), only 10-30% of individuals with damaging mutations in the complement component 2 (C2) gene develop the disease [15]. Conversely, epidemiological studies consistently demonstrate that not all individuals exposed to an environmental risk factor develop the associated condition, highlighting the role of underlying genetic susceptibility.

This whitepaper examines the converging evidence from human studies and experimental models that reveals how these interactions operate at molecular, cellular, and systems levels. By framing our discussion within immune variation research, we aim to provide drug development professionals and researchers with a comprehensive technical resource that bridges fundamental mechanisms with translational applications.

Molecular Mechanisms of Gene-Environment Interactions

Epigenetic Mediation: The Biological Memory of Exposure

Epigenetics represents a primary molecular mechanism through which environmental exposures interface with the genome to influence disease risk. Epigenetic modifications—including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs—regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [16] [17]. These modifications create a dynamic "molecular memory" of environmental exposures that can persist long after the exposure has ended [17].

The epigenome functions analogously to a conductor's annotations on a musical score—while the notes (genes) remain unchanged, the annotations (epigenetic marks) dramatically alter how the music is performed [17]. Environmental factors—from chemical toxicants to psychosocial stress—can rewrite these epigenetic annotations, potentially leading to immune dysregulation and disease pathogenesis [16] [18].

Table 1: Environmental Exposures and Their Epigenetic Mechanisms in Autoimmune Disease

| Exposure Category | Specific Exposures | Epigenetic Mechanism | Associated Autoimmune Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Factors | Silica, organic solvents | DNA hypomethylation, histone modifications | Systemic sclerosis, SLE, rheumatoid arthritis |

| Medications | Procainamide, hydralazine | DNA methyltransferase inhibition | Drug-induced lupus |

| Physical Factors | Ultraviolet (UV) radiation | Altered DNA methylation in keratinocytes | Cutaneous lupus, SLE flares |

| Biological Factors | Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection | DNA methylation changes in immune cells | Multiple sclerosis, SLE, rheumatoid arthritis |

| Lifestyle Factors | Cigarette smoking | DNA methylation changes, histone modifications | Rheumatoid arthritis, SLE |

Notably, these environmentally-induced epigenetic changes can exhibit tissue specificity and may be heritable across cell divisions, creating persistent alterations in cellular function [17]. In some cases, these modifications can even be transmitted transgenerationally through germ cells, as demonstrated in mouse studies where chronic psychosocial stress altered DNA methylation patterns in male germ cells and affected offspring development [16].

Immune System as the Convergence Interface

The immune system serves as a particularly sensitive interface for gene-environment interactions due to its requirement for dynamic responsiveness to environmental challenges while maintaining tolerance to self-antigens. Research has demonstrated that environmental factors can disrupt peripheral tolerance mechanisms, particularly those mediated by regulatory T cells (Tregs), in genetically susceptible individuals [19].

In autoimmune diseases, Tregs often exhibit intrinsic signalling defects despite normal frequencies. Recent evidence identifies impaired IL-2 receptor (IL-2R) signal durability as a key mechanism, linked to aberrant degradation of signalling components like phosphorylated JAK1 and DEPTOR [19]. This dysfunction stems from diminished expression of GRAIL, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that regulates these signalling molecules.

Table 2: Quantitative Contributions of Genetic vs. Environmental Factors to Disease Risk

| Disease/Condition | Genetic Contribution | Environmental Contribution | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Depression | ~37% of susceptibility | Significant role of early-life stress, caregiver mental health | Twin and adoption studies [16] |

| Anxiety Disorders | 30-50% of variance | Trauma, socioeconomic factors | Meta-analysis of twin studies [16] |

| Type 2 Diabetes | Lower predictive value | Higher predictive value of environmental score | Polygenic vs. polyexposure score comparison [20] |

| Autoimmune Diseases | Strong MHC association | Infections, silica, solvents, UV radiation | GWAS and epidemiological studies [19] [18] |

| Immune Cell Composition | Varies by cell type | Strong environmental influence | Rewilded mouse studies [6] |

The convergence of genetic risk variants with environmental triggers creates a permissive environment for breaking self-tolerance. For example, in rheumatoid arthritis, the interaction between HLA-shared epitope alleles and smoking history significantly increases disease risk compared to either factor alone [18].

Methodological Approaches for Studying Gene-Environment Interactions

Advanced Study Designs and Analytical Frameworks

Investigating gene-environment interactions requires sophisticated methodological approaches that can simultaneously capture genetic and environmental contributions. Traditional candidate gene-environment interaction studies have evolved into more comprehensive genome-wide interaction studies (GWIS) that examine the entire genome for loci whose effects on disease are modified by environmental factors [21].

The emergence of the exposome concept—encompassing the totality of environmental exposures from conception onward—has driven development of novel exposure assessment methods [17]. High-resolution metabolomics can now simultaneously measure up to 1,000 chemicals, providing a more holistic view of the internal chemical environment [17]. These advances are complemented by computational methods that use epigenetic fingerprints to reconstruct past exposures, even when the causative chemicals are no longer detectable [22].

The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework has been developed as a tool to support environmental risk assessment by systematically organizing evidence linking molecular initiating events through intermediate key events to adverse health outcomes [18]. This structured approach helps distinguish correlational from causal relationships between environmental exposures and disease outcomes through epigenetic modifications.

The "Rewilded" Mouse Model: An Experimental Paradigm

Experimental Protocol: Rewilding and Trichuris muris Infection

Objective: To quantify the relative and interactive contributions of genetic and environmental influences on immune phenotypes and helminth susceptibility.

Subjects: Female inbred mice of strains C57BL/6, 129S1, and PWK/PhJ (genetically diverse founders of the Collaborative Cross).

Experimental Groups:

- Laboratory controls: Housed in conventional vivarium with summer-like temperatures and photoperiods

- Rewilded: Housed in outdoor enclosure for natural environmental exposure

Procedure:

- Randomly assign mice to laboratory or rewilding groups (n=135 total across two experimental blocks)

- Acclimate rewilding group to outdoor enclosure for 2 weeks

- Infect approximately half of each group with 200 embryonated Trichuris muris eggs

- Return infected mice to their respective environments for 3 weeks

- Collect peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) for spectral cytometry analysis

- Perform complete blood count with differential (CBC/DIFF) at 2 and 5 weeks post-rewilding

- Analyze worm burden and immune parameters

Analytical Methods:

- Multivariate distance matrix regression (MDMR) to quantify contributions of genotype, environment, and infection to immune variation

- Principal component analysis (PCA) on PBMC cellular composition data

- k-means clustering for unbiased immune cell population identification

Key Findings:

- Cellular composition was shaped by interactions between genotype and environment

- Cytokine response heterogeneity, particularly IFNγ concentrations, was primarily driven by genotype with consequences for worm burden

- Genetic differences observed under laboratory conditions were decreased following rewilding

- CD44 expression on T cells was explained mostly by genetics, while on B cells was explained more by environment [6]

Diagram 1: Rewilded Mouse Experimental Paradigm. This workflow illustrates the interactive effects of genotype, environment, and infection on immune phenotypes and functional outcomes in the rewilded mouse model.

Polyexposure Scoring: Quantifying Environmental Risk

The development of polyexposure scores represents a significant advancement in quantifying cumulative environmental risk, analogous to polygenic risk scores in genetics. Recent research from the Personalized Environment and Genes Study (PEGS) demonstrates that polyexposure scores often outperform polygenic scores in predicting chronic disease development [20].

In one analysis, researchers computed three complementary risk scores:

- Polygenic score: Combined genetic risk based on 3,000 genetic traits

- Polyexposure score: Combined environmental risk from modifiable exposures (occupational hazards, lifestyle choices, stress)

- Polysocial score: Combined social risk from factors like socioeconomic status and housing

Notably, for conditions like type 2 diabetes, environmental and social risk scores demonstrated superior predictive performance compared to genetic risk scores alone [20]. This approach highlights the importance of integrating comprehensive environmental exposure data alongside genetic information for accurate disease risk prediction.

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Gene-Environment Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Technical Specifications | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution Metabolomics | Simultaneous measurement of up to 1,000 chemicals | LC-MS/MS platforms, computational analysis of metabolic pathways | [17] |

| Epigenetic Clock Assays | Assessment of biological aging and exposure memory | Bisulfite sequencing for DNA methylation analysis at age-related CpG sites | [17] |

| Spectral Cytometry Panels | High-dimensional immune phenotyping | 30+ parameter flow cytometry, automated population discovery | [6] |

| Extracellular Vesicle Isolation Kits | Non-invasive tissue-specific biomarker analysis | Immunoaffinity capture of neuron-, lung-, or liver-derived vesicles | [17] |

| GWAS/EWAS Arrays | Genome-wide and epigenome-wide association studies | Microarray or sequencing-based genotyping/methylation profiling | [15] |

| MARIO Computational Pipeline | Identification of allele-dependent binding of regulatory proteins | Analysis of allelic imbalance in ChIP-seq and other functional genomics data | [15] |

Signalling Pathways in Gene-Environment Interactions

IL-2 Receptor Signalling Dysregulation in Autoimmunity

The IL-2 receptor signalling pathway represents a critical convergence point for genetic and environmental influences on immune tolerance. Recent research has identified a novel mechanism in which environmental triggers exacerbate intrinsic Treg defects in genetically susceptible individuals, leading to autoimmune pathogenesis [19].

In healthy Tregs, IL-2 binding activates the JAK-STAT pathway through phosphorylation of JAK1 and JAK3, leading to STAT5 activation and nuclear translocation. This signalling is regulated by a negative feedback mechanism involving GRAIL (Gene Related to Anergy in Lymphocytes), an E3 ubiquitin ligase that inhibits cullin RING ligase activation and prevents aberrant degradation of signalling components [19].

In autoimmune patients, diminished GRAIL expression results in accelerated degradation of phosphorylated JAK1 and DEPTOR (an mTOR inhibitor), leading to compromised IL-2R signal durability despite normal surface receptor expression. This signalling defect impairs Treg suppressive function without necessarily reducing Treg frequency [19].

Diagram 2: IL-2 Receptor Signaling Dysregulation. This pathway illustrates how reduced GRAIL expression in autoimmune disease leads to compromised Treg function through accelerated degradation of signaling components.

Epigenetic Dysregulation by Environmental Exposures

Environmental exposures can initiate epigenetic modifications through several well-characterized molecular pathways. Chemical exposures such as benzene, toluene, and diesel exhaust have been associated with oxidative stress, leading to DNA damage and mutations in germ cells that can affect offspring neurodevelopment [22].

Specific mechanisms include:

- DNA methyltransferase inhibition: Chemicals like procainamide directly inhibit DNMT enzymes, leading to global DNA hypomethylation [18]

- Histone modification alterations: Pesticides like dieldrin have been shown to increase histone acetylation, promoting apoptosis in dopaminergic neurons [18]

- MicroRNA dysregulation: Air pollution components can alter miRNA expression profiles, affecting immune gene regulation [22]

These epigenetic changes create persistent alterations in gene expression patterns that can predispose to autoimmune, neurodevelopmental, and metabolic disorders, often in a tissue-specific manner that reflects the route and timing of exposure.

Translational Applications and Future Directions

Precision Environmental Health and Therapeutic Development

The Convergence Model provides a robust framework for developing targeted therapeutic interventions. One promising approach involves neddylation activating enzyme inhibitors (NAEis) conjugated to IL-2 or anti-CD25 antibodies to selectively restore Treg function in autoimmune patients [19]. This strategy addresses the core immune dysregulation without inducing systemic immunosuppression.

The emerging field of precision environmental health (PEH) aims to integrate genetic, epigenetic, and exposure data to develop personalized prevention strategies. PEH encompasses three major knowledge domains: environmental exposures, genetics (including epigenetics), and data science [17]. This approach represents a cultural shift from reactive "disease care" to proactive health preservation by identifying at-risk individuals before disease manifestation.

Epigenetic biomarkers show particular promise for early detection and intervention. Research has demonstrated that epigenetic signatures can accurately predict prenatal exposure to environmental toxicants like tobacco smoke years after the actual exposure occurred [22]. Similar approaches are being developed for air pollution, PFAS, and other chemical exposures, potentially enabling targeted screening of high-risk children for pollution-related conditions like asthma.

Research Gaps and Methodological Challenges

Despite significant advances, substantial challenges remain in fully elucidating gene-environment interactions. Key research gaps include:

- Exposure assessment complexity: The vast scope of the exposome, encompassing exposures from conception onward, creates measurement challenges [17]

- Temporal dynamics: The timing of exposures, particularly during critical developmental windows, significantly influences their biological impact [22]

- Multi-omics integration: Synthesizing data from genome, epigenome, metabolome, and proteome requires advanced computational approaches [22]

- Ancestral diversity: Current datasets are disproportionately focused on European-ancestry populations, limiting generalizability [15]

Future research directions should prioritize the development of novel computational methods, including artificial intelligence approaches, to integrate multi-omics data and identify critical exposure thresholds. Additionally, expanding diverse population studies and longitudinal birth cohorts will be essential for capturing the full spectrum of gene-environment interactions across the lifespan.

The Convergence Model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how genetic predisposition and environmental factors interact to drive disease pathogenesis. Through epigenetic mechanisms, immune system modulation, and complex signalling pathway alterations, these interactions create distinct biological trajectories that influence disease risk and progression.

The methodological advances detailed in this review—from rewilded animal models to polyexposure scoring and epigenetic fingerprinting—provide researchers and drug development professionals with powerful tools to investigate these interactions. The translation of these findings into precision environmental health approaches holds exceptional promise for revolutionizing disease prevention and developing targeted therapies that address the fundamental convergence of genetic and environmental factors in human disease.

As the field advances, integrating comprehensive environmental exposure assessment with deep molecular phenotyping will be essential for unlocking the full potential of the Convergence Model to improve human health and mitigate disease risk across diverse populations.

The immune system demonstrates profound sexual dimorphism, influencing health, disease, and therapeutic outcomes across the lifespan. Understanding sex as a biological variable (SABV) is no longer optional but essential for rigorous immunological research and the development of precision medicine. Sex-based disparities in immune function are evident in the higher prevalence of autoimmune diseases in females and the increased susceptibility to severe infections and many cancers in males [23]. These differences arise from a complex interplay of genetic determinants, primarily the sex chromosomes, and endocrine factors, notably sex hormones, which collectively shape immune cell composition, function, and aging trajectories [23] [24]. Framing this within the broader context of genetics and environment, this whitepaper synthesizes current evidence on the chromosomal and hormonal mechanisms driving immune variation, providing researchers with a technical guide and methodological toolkit for integrating SABV into immunology research and drug development.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Sexual Dimorphism

The foundations of immune sex differences are established by two core biological systems: the sex chromosomes, which provide a genetic blueprint, and the sex hormones, which exert dynamic regulatory control. These systems act both independently and through complex crosstalk.

Chromosomal Influences

The sex chromosomes confer genetic differences that are present from conception and operate in every nucleated cell, including those of the immune system.

- X-Chromosome Gene Dosage and Inactivation Escape: The X chromosome is enriched for immune-related genes. To achieve dosage compensation between females (XX) and males (XY), one X chromosome is randomly inactivated in female somatic cells through an epigenetic process mediated by XIST (X-inactive specific transcript) [23]. However, approximately 15-25% of X-chromosome genes escape this inactivation, leading to their biallelic expression and higher expression levels in females [25] [23]. This double dose of immune-relevant escape genes, such as TLR7 (a pattern-recognition receptor critical for viral RNA sensing), provides females with a more robust innate immune detection system and contributes to a stronger antibody response [25]. The reactivation of X-linked genes can also occur in specific immune cell types, such as activated B and T cells, further amplifying sex differences in adaptive immunity [23].

- Y-Chromosome and Immune Function: The Y chromosome, once considered a genetic wasteland, is now known to influence immunity. The loss of the Y chromosome (LOY) in a subset of immune cells, particularly hematopoietic cells, is a common age-related mosaic event in men [23]. LOY is associated with altered immune cell function, increased risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and a shortened lifespan, suggesting a role for Y-linked genes in maintaining immune homeostasis and health in aging males [23].

Hormonal Regulation

Sex hormones, including estrogens, androgens, and progesterone, exert widespread effects on immune cell development, differentiation, and effector functions via genomic and non-genomic signaling pathways.

- Estrogen Signaling: Estrogens, primarily 17β-estradiol, generally enhance both innate and adaptive immunity. Signaling occurs through classical nuclear estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), which act as transcription factors, or through membrane-bound G protein-coupled estrogen receptors (GPER) for rapid non-genomic effects [26]. Estrogen enhances neutrophil activation, antigen presentation by dendritic cells, and the cytolytic function of NK cells [25] [26]. It also promotes B cell development and antibody production by directly activating the expression of Activation-Induced Cytidine Deaminase (AID), a key enzyme for antibody class-switch recombination and somatic hypermutation [26]. Furthermore, estrogen can expand the CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell (Treg) compartment, illustrating its role in immune modulation [26].

- Androgen Signaling: Androgens, such as testosterone, typically have immunosuppressive effects [26]. Androgen receptor (AR) signaling can dampen inflammatory responses by reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and promoting anti-inflammatory profiles [26]. In the context of cancer, the AR fosters an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, and AR blockade in prostate cancer can reinvigorate antitumor T cell responses [26].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms through which chromosomes and hormones influence immune cell function.

Quantitative Evidence of Sex Differences in Immunity

Empirical data from human studies robustly document sex differences in immune cell proportions and molecular profiles. These differences are present in early life and evolve across the lifespan.

Immune Cell Proportions

Longitudinal pediatric studies leveraging DNA methylation (DNAm)-based computational cell type deconvolution reveal that significant sex differences in immune cell composition are established before puberty. Research on whole blood samples from children at ages one and five shows dynamic changes in all immune cell types during early development, with notable sex-associated differences [27].

Table 1: Sex-Associated Differences in Immune Cell Proportions in Early Life (Ages 1 and 5)

| Immune Cell Type | Sex-Bias | Developmental Window | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basophils | Significantly different | Ages 1 & 5 | Consistent difference across early childhood [27] |

| CD4+ Memory T cells | Significantly different | Ages 1 & 5 | Consistent difference across early childhood [27] |

| T Regulatory Cells (Tregs) | Significantly different | Ages 1 & 5 | Consistent difference across early childhood [27] |

| Monocytes | Male-biased | By age 5 | Higher proportion in males emerges by age 5 [27] |

| CD8+ Naive T cells | Female-biased | By age 5 | Higher proportion in females emerges by age 5 [27] |

In adulthood, hormonal influences become more pronounced. A study analyzing blood samples from a cross-sectional cohort including cisgender, transgender, and post-menopausal individuals found that class-switched memory B cells—critical for high-affinity, long-lived antibody responses—are present at higher levels in cisgender females compared to cisgender males only between puberty and menopause [28]. This difference was dependent on both oestrogen and an XX chromosomal background, as it was not observed in transgender females (XY) taking estrogen, but was reduced in transgender males (XX) undergoing estrogen-blocking therapy [28].

Epigenetic and Molecular Signatures

Epigenetic mechanisms, particularly DNA methylation (DNAm), provide a molecular footprint of immune system maturation and sexual dimorphism. Analysis of over 4,900 CpG sites across 628 immune system candidate genes in pediatric cohorts identified distinct sex-associated DNAm signatures that were consistent between ages one and five, indicating stable early-life programming independent of pubertal hormones [27]. While age-related DNAm changes were relatively limited in this window, sex-associated differences were more prominent and partially validated in independent cohorts [27]. This suggests that the epigenetic landscape of the immune system is shaped by sex from a very young age, potentially setting the stage for lifelong differences in immune function and disease risk.

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

To rigorously study sex differences in immunology, researchers require robust, reproducible methodologies. Below are detailed protocols for key approaches cited in this field.

DNA Methylation Analysis for Immune Profiling

This protocol allows for the simultaneous assessment of immune cell proportions and epigenetic age- or sex-associated signatures from whole blood [27].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Immune Cell Deconvolution & Epigenetics

| Research Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Whole Blood Sample | Source of genomic DNA for methylation profiling and cellular analysis. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Chemically modifies unmethylated cytosines to uracils, allowing for methylation status determination. |

| Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip | Microarray platform for high-throughput genotyping of over 850,000 CpG methylation sites across the genome. |

| DNA Methylation Deconvolution Algorithms | Computational tools that use reference methylation signatures to estimate proportions of specific immune cell types from heterogeneous tissue data. |

| Robust Linear Regression Models | Statistical method used to identify CpG sites whose methylation status is significantly associated with sex or age, resistant to outliers. |

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Collection & DNA Extraction: Collect peripheral whole blood in EDTA or citrate tubes. Extract high-molecular-weight genomic DNA using a standardized kit. Quantify DNA purity and concentration via spectrophotometry.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat 500 ng of genomic DNA with sodium bisulfite using a commercial kit. This step deaminates unmethylated cytosine residues to uracil, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged.

- Whole Genome Amplification & Hybridization: Amplify the bisulfite-converted DNA and fragment it enzymatically. The fragmented DNA is hybridized to the Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip, which contains probe sequences designed to distinguish between methylated and unmethylated alleles.

- Scanning & Data Preprocessing: Scan the BeadChip to fluorescence intensities. Preprocess the raw data using R/Bioconductor packages (e.g.,

minfi) for background correction, dye-bias normalization, and calculation of beta-values (β = methylated signal / (methylated + unmethylated signal)). β-values range from 0 (completely unmethylated) to 1 (fully methylated). - Cell Type Deconvolution: Input the normalized β-values into a DNAm deconvolution algorithm (e.g.,

HousemanorEpiDISH). The algorithm uses a pre-established reference matrix of cell-specific methylation marks to estimate the relative proportion of various immune cell types (e.g., neutrophils, B cells, T cell subsets, monocytes) in each sample. - Differential Methylation Analysis: To identify sex-associated DNAm signatures, model the β-value of each CpG site as the dependent variable in a robust linear regression, with sex as the independent variable. Correct for multiple testing using False Discovery Rate (FDR). Apply a threshold (e.g., FDR < 0.05 and |Δβ| > 0.03) to identify statistically and biologically significant sites.

Isolating Chromosomal vs. Hormonal Effects

The "Four Core Genotypes" (FCG) mouse model is a powerful tool to dissect the independent contributions of chromosomes (XX vs. XY) and gonads (ovaries vs. testes) to a phenotype [24].

Experimental Model:

- The FCG model is generated by translocating the testis-determining gene Sry from the Y chromosome to an autosome. This results in four distinct genotypes:

- XX with Ovaries (typical female)

- XY with Ovaries

- XX with Testes

- XY with Testes (typical male)

Workflow for Immune Profiling:

- Model Generation & Validation: Genotype mice to confirm XX or XY karyotype in the absence of the Sry gene on the Y chromosome. Verify gonad type (ovary or testis) by histology or hormone level measurement (e.g., plasma estradiol, testosterone).

- Immune Challenge or Baseline Analysis: Subject mice from all four groups to an immune challenge (e.g., viral infection, vaccination, or tumor implantation) or analyze their immune systems at baseline.

- Outcome Measurement: Collect relevant tissues (blood, spleen, lymph nodes). Analyze using flow cytometry (for immune cell populations), ELISA or Luminex (for cytokine/antibody levels), and/or functional assays (e.g., T cell killing, phagocytosis).

- Statistical Modeling: Use a 2x2 factorial design to test the main effects of Chromosome Type (XX vs. XY) and Gonad Type (Ovary vs. Testis), and their interaction, on the immune outcome of interest. A significant effect of chromosome, independent of gonad type, indicates a direct genetic contribution.

The following diagram maps this experimental strategy.

Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

The documented sex differences in immunity have significant consequences for disease susceptibility, treatment efficacy, and the future of precision medicine.

Disease Susceptibility and Vaccine Responses

The female immune advantage manifests as stronger responses to vaccination and greater resistance to many viral and bacterial infections [25]. However, this heightened immune reactivity comes at the cost of a 3- to 4-fold higher risk of developing autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [25] [23]. Conversely, males exhibit a higher incidence and mortality for many non-reproductive cancers, a disparity influenced by both immunosuppressive androgenic environments and sex chromosome effects [23] [26].

Cancer Immunotherapy

Sex is a significant predictor of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Meta-analyses of clinical trials have shown that the survival benefit from anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-(L)1 monotherapy is generally greater for men across various solid tumors [26]. This appears context-dependent, however, as women may derive greater benefit from combinations of chemotherapy with anti-PD-(L)1 in non-small cell lung cancer [26]. The androgen receptor (AR) is recognized as a key driver of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, making it a promising therapeutic target. Preclinical and early clinical evidence suggests that AR blockade can synergize with ICIs, enhancing antitumor T cell responses and improving outcomes [26].

The integration of SABV into immunological research is critical for advancing science and health equity. Future efforts must focus on:

- Elucidating Mechanisms: Deepening our understanding of how XCI escape genes and LOY precisely alter specific immune cell functions at the molecular level.

- Lifespan Studies: Conducting longitudinal studies that capture immune variation across all life stages, from infancy to advanced age, and during key hormonal transitions like puberty, pregnancy, and menopause [24].

- Inclusive Study Designs: Moving beyond the male-default and intentionally including both sexes in preclinical and clinical research, with appropriate statistical power to analyze sex-specific outcomes [24].

- Global Immune Profiling: Large-scale initiatives like the Human Immunome Project aim to generate the largest immunological dataset ever created, mapping global immune variation. This will powerfully enable the identification of sex-specific immune signatures and the development of predictive models for precision medicine [29].

In conclusion, sex is a fundamental biological variable that exerts a profound influence on the immune system through interconnected chromosomal and hormonal pathways. Acknowledging and systematically investigating these differences is not merely a box-ticking exercise but a scientific imperative. It is the key to unlocking a deeper understanding of immune function, developing more effective and personalized therapeutics, and ultimately improving health outcomes for all.

The relative contributions of genetic inheritance and environmental exposure to phenotypic variation represent a foundational question in biology, often simplified as the "nature versus nurture" debate [30]. In the specific field of immunology, resolving this question is critical for understanding the vast inter-individual heterogeneity in immune responses observed in health, disease, and following interventions such as vaccination [31] [32]. Framed within a broader thesis on the determinants of immune variation, this whitepaper synthesizes insights from key twin and population studies to provide a technical guide on the methodologies, findings, and implications of quantifying heritable and non-heritable influences on the immune system. Accurate quantification is not merely an academic exercise; it holds profound consequences for identifying disease risk, predicting therapeutic outcomes, and guiding the development of novel immunomodulatory drugs [6] [7].

Core Concepts and Definitions of Heritability

Heritability is formally defined as the proportion of observed phenotypic variation (VP) in a population that is attributable to genetic variation [30] [33]. It is crucial to recognize that heritability is a population-level statistic, not an individual-level measure, and its value can change depending on the population and environment studied [30].

- Narrow-Sense Heritability (h²): This estimates the proportion of phenotypic variance explained solely by additive genetic effects (VA), where the effects of different alleles add up linearly. It is defined as h² = VA/VP. This is the most relevant metric for predicting the response to natural or artificial selection and is the parameter typically estimated in genomic studies [30] [33].

- Broad-Sense Heritability (H²): This estimates the proportion of phenotypic variance explained by total genetic variance (VG), which includes additive, dominant, and epistatic (gene-gene interaction) effects. It is defined as H² = VG/VP [30] [33].

A common misconception is that a heritability of 80% for a trait means that 80% of an individual's phenotype is determined by genes and 20% by environment. The correct interpretation is that within the studied population, 80% of the variation in the trait is associated with genetic differences between individuals [30].

Key Methodologies for Estimating Heritability

Several experimental and statistical approaches are employed to disentangle genetic and environmental influences, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and underlying assumptions.

Family-Based Designs

- Classic Twin Study (ACE Model): This is a cornerstone design. It compares phenotypic similarity between monozygotic (MZ) twins, who share nearly 100% of their DNA, and dizygotic (DZ) twins, who share approximately 50% on average. The model partitions variance into:

- A (Additive genetic factors): Inferred if MZ twin correlation is greater than DZ twin correlation.

- C (Common/Shared environment): Inferred if MZ and DZ twins show similar correlations.

- E (Unique/Non-shared environment): Inferred from the extent to which MZ twins are dissimilar. A critical assumption is the Equal Environment Assumption (EEA), which posits that MZ and DZ twins experience equally similar environments [33]. Violations of this assumption can inflate heritability estimates [34] [33].

- Sibling Regression (SR): This method uses the genetic similarity of full siblings (who also share ~50% of their DNA) but relies on within-family variation, making it less susceptible to confounding from population stratification. However, it can be biased by sibling-specific environmental effects and captures some gene-gene and gene-environment interactions [34] [33].

Genomic Designs

- Genomic Relatedness Restricted Maximum-Likelihood (GREML): Used in Genome-Wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA), this method estimates the proportion of phenotypic variance explained by all common genetic variants measured on a genome-wide SNP array across unrelated individuals. It estimates narrow-sense heritability free from the assumptions of the twin design but can be confounded by environmental factors correlated with genetic relatedness [34] [33].

- Linkage Disequilibrium Score Regression (LDSR): This method uses summary statistics from Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS). It regresses SNP test statistics on their Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) scores. SNPs in high-LD regions tag more causal variants and thus have higher average test statistics. The slope of this regression estimates SNP heritability, and the intercept can detect confounding biases [33].

- Relatedness Disequilibrium Regression (RDR): A within-family method that leverages the random variation in genetic sharing between parents and offspring. It is considered highly robust as it is immune to environmental confounding and assortative mating, providing a clean estimate of narrow-sense heritability [34].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Heritability Estimation Methods

| Method | Study Design | Variance Components Estimated | Key Assumptions | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classic Twin (ACE) | MZ vs. DZ twins | A, C, E | Equal environments for MZ/DZ twins (EEA); Random mating | EEA violation inflates estimates; Cannot model GxE well |

| Sibling Regression (SR) | Full siblings | Additive + some interactions | No systematic environmental differences between siblings | Sensitive to sibling-specific environments |

| GREML | Unrelated individuals | Additive (SNP-based) | No environmental correlation with genetic relatedness | Confounded by population stratification |

| LDSR | GWAS summary stats | Additive (SNP-based) | LD score uncorrelated with effect size | Less accurate with fewer SNPs |

| RDR | Parent-offspring trios | Additive (narrow-sense) | Random segregation of alleles | Requires genotyped trios; Lower power |

Quantitative Findings in Immune System Variation

Applying these methodologies has yielded a nuanced picture of the architecture of immune variation, revealing a system predominantly shaped by non-heritable factors but with critical genetic contributions.

Insights from Large-Scale Human Twin Studies

A seminal systems-level analysis of 210 healthy twins measured 204 immunological parameters, including cell population frequencies, cytokine responses, and serum proteins [31] [35].

Table 2: Summary of Heritability Findings from a Systems-Level Twin Study [31] [35]

| Immune Parameter Category | Key Findings | Examples of Highly Heritable Traits | Examples of Non-Heritable Dominated Traits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Population Frequencies (72 subsets) | 61% of cell populations had undetectable heritable influence (<20%) [31]. | Naïve & central memory CD4+ T cells (CD27+) [31]. | Most innate (granulocytes, monocytes, NK-cells) and adaptive cells [31]. |

| Serum Proteins (43 cytokines, chemokines, growth factors) | Majority dominated by non-heritable influences; some notable exceptions [31]. | IL-12p40 (associated with IL12B gene variants) [31]. | IL-10 and a group of chemokines [31]. |

| Cellular Signaling Responses (65 induced responses) | 69% of signaling responses had no detectable heritable influence (<20%) [31]. | IL-2 and IL-7 induced STAT5 phosphorylation in T-cells (homeostatic) [31]. | IFN-induced STAT1 phosphorylation; IL-6/IL-21/IL-10 induced STAT3 phosphorylation [31]. |

| Overall Summary | 77% of all 204 parameters were dominated (>50% of variance) by non-heritable influences. 58% were almost completely determined (>80% of variance) by non-heritable influences [31] [35]. |

The study further found that variation in immune parameters between MZ twins increases with age, suggesting the cumulative effect of environmental exposures [31] [35]. Furthermore, a single non-heritable factor, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, can significantly alter over half of all measured immune parameters, underscoring the powerful and pervasive role of environment [31] [35].

The Role of Genotype-by-Environment (GxE) Interactions

Controlled animal studies provide direct evidence for GxE interactions, where the effect of a genotype depends on the environment and vice-versa. Research using "rewilded" mice—laboratory strains introduced into a natural outdoor environment—demonstrated that immune variation is often shaped by synergistic interactions between genetics and environment, not just their independent effects [6] [36].

Table 3: Key Findings from Rewilded Mouse Studies on GxE Interactions [6] [36]

| Aspect of Immune Variation | Finding | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Composition | Shaped by significant interactions between genotype and environment (Gen x Env) [6]. | The impact of a mouse's strain on its immune cell profile depends on whether it lives in a lab or a natural environment. |

| Cytokine Responses | Primarily driven by genotype, with consequences for parasite burden [6]. | Genetic background is a major determinant of functional cytokine output upon challenge. |

| Marker Expression (e.g., CD44) | Expression on T cells was explained more by genetics, while on B cells it was explained more by environment [6]. | The relative influence of genes and environment can be cell-type-specific. |

| Emergence of Genetic Effects | A stronger Th1 response to Trichuris muris in C57BL/6 mice emerged only in the rewilding condition, not in the lab [6]. | Environmental context can reveal or mask genetic differences in immune responses. |

| Reduction of Genetic Effects | Genetic differences in CD44 expression on CD4+ T cells between strains, evident in the lab, were no longer present after rewilding [6]. | A shifting environment can erase genetically determined differences seen in controlled settings. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols