Decoding TCR-pMHC Interactions: From Fundamental Principles to Therapeutic Applications in Adaptive Immunity

This article provides a comprehensive examination of T-cell receptor (TCR) and peptide-major histocompatibility complex (pMHC) interactions, the cornerstone of adaptive cellular immunity.

Decoding TCR-pMHC Interactions: From Fundamental Principles to Therapeutic Applications in Adaptive Immunity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of T-cell receptor (TCR) and peptide-major histocompatibility complex (pMHC) interactions, the cornerstone of adaptive cellular immunity. We explore the fundamental thermodynamic, kinetic, and mechanical principles governing these interactions, highlighting how they confer both incredible specificity and necessary cross-reactivity. The content details state-of-the-art computational and experimental methodologies, including AlphaFold and TCR engineering, for predicting and manipulating these interactions. A significant focus is placed on troubleshooting challenges in immunotherapy development, such as off-target toxicity and affinity-optimization pitfalls. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of preclinical validation frameworks for TCR-based therapies, offering researchers and drug development professionals a structured guide to navigating this complex field from basic science to clinical translation.

The Structural and Energetic Blueprint of TCR-pMHC Recognition

Adaptive immunity provides vertebrates with the remarkable ability to recognize and remember a vast array of pathogens, offering long-lasting protection against reinfection. This sophisticated defense system is fundamentally rooted in the specific interactions between T cell receptors (TCRs) and peptide-major histocompatibility complexes (pMHCs). TCRs, generated through somatic recombination of genomic DNA segments during T cell development, confer a unique antigen specificity to each T cell clone, establishing its clonal identity [1]. These receptors continuously survey the body for antigenic ligands—short peptide fragments bound to MHC class I or II molecules presented on the surface of antigen-presenting cells [1]. The exquisite sensitivity and specificity of this interaction enables T cells to discriminate with remarkable precision between foreign peptides derived from pathogens and similar self-peptides derived from host tissues, a crucial capability for maintaining both effective immunity and self-tolerance [1] [2]. This discriminative power is particularly astonishing given the relatively small differences in affinity between agonist pMHC (typically 1-10 μM) and self-pMHC (typically only 10-fold weaker) [1]. Understanding the mechanisms governing TCR-pMHC interactions therefore represents a cornerstone of immunology, with profound implications for vaccine development, cancer immunotherapy, and the treatment of autoimmune disorders.

Quantitative Fundamentals of TCR-pMHC Interactions

The interaction between a TCR and its cognate pMHC ligand can be quantitatively described through thermodynamic, kinetic, and mechanical parameters. These properties collectively determine the outcome of T cell recognition, influencing whether a T cell becomes activated, remains inert, or enters a state of anergy.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters of TCR-pMHC Interactions

| Parameter | Definition | Biological Significance | Typical Range for Agonists |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity (KD) | Equilibrium dissociation constant; measure of binding strength [2] | Determines thermodynamic stability of the TCR-pMHC complex [2] | 1-10 μM [1] |

| Association Rate (kon) | Rate constant for complex formation [2] | Influences speed of initial recognition and serial engagement [1] | Variable |

| Dissociation Rate (koff) | Rate constant for complex dissociation [2] | Determines complex lifetime (residence time); critical for kinetic proofreading [2] | Variable |

| Residence Time (Ï„) | Average lifetime of the TCR-pMHC complex; Ï„ = 1/koff [2] | Dictates duration of signaling; allows accumulation of downstream signals [2] | Sufficient for kinetic proofreading steps |

| 3D Affinity | Binding strength in solution [1] | Governs initial binding event | 1-10 μM [1] |

| 2D Affinity | Binding strength at the cell-cell interface [2] | More physiologically relevant for T cell activation in the immune synapse | Dependent on membrane environment |

The discrimination between agonist and self-pMHC ligands cannot be explained by affinity alone, as the free energy differences are often minimal [2]. This paradox is resolved by incorporating kinetic selectivity and the concept of kinetic proofreading. Kinetic selectivity (Sk) is defined as the ratio of association rates for competing ligands (Sk = konpMHC1/konpMHC2), while kinetic proofreading describes a mechanism where a series of signaling events must accumulate before TCR-pMHC dissociation occurs [1] [2]. This multi-step process consumes energy at each step and amplifies the small initial differences in binding properties, enabling the T cell to distinguish between closely related ligands with high fidelity [2].

Structural Dynamics and Allosteric Mechanisms

The structural basis of TCR-pMHC recognition involves considerable conformational dynamism, with both proteins existing as ensembles of interconverting states rather than single static structures [3]. X-ray crystallography has provided foundational high-resolution snapshots of TCR-pMHC complexes, but these static images often conceal the extensive flexibility inherent to these molecules [3]. For instance, comparisons of identical molecules in different crystal lattices have suggested a "scanning" motion of the TCR on pMHC, a phenomenon further supported by molecular dynamics (MD) studies [3].

Recent structural and computational studies have revealed an allosteric mechanism for TCR triggering, wherein pMHC binding induces conformational changes that propagate through the receptor complex. The TCRβ FG loop serves as a critical "gatekeeper," preventing accidental triggering, while the connecting peptide region acts as a hinge for essential conformational changes [4]. Upon pMHC engagement, the TCR extracellular domain tilts away from the CD3 proteins, transitioning from a bent conformation (approximately 104°) to a more extended conformation (approximately 150°) [4]. This structural rearrangement reduces contacts between the TCRβ variable domain and the CD3γε dimer, thereby increasing CD3 mobility—a key step in signal initiation [4].

Table 2: Key Structural Elements in TCR-pMHC Signaling

| Structural Element | Location/Composition | Function in TCR Signaling |

|---|---|---|

| ITAM Motifs | Cytoplasmic tails of CD3 and ζ chains [1] | Phosphorylated by Lck to create docking sites for Zap70 [1] |

| CD4/CD8 Coreceptors | T cell surface [1] | Recruit Lck to the TCR-pMHC complex [1] |

| TCRβ FG Loop | TCRβ chain [4] | Acts as gatekeeper; transmits force from pMHC binding site [4] |

| Connecting Peptide | Between extracellular and transmembrane domains [4] | Serves as hinge for conformational changes upon pMHC binding [4] |

| CDR3 Regions | Hypervariable loops of TCR α and β chains [5] | Primary determinants of peptide specificity [5] |

TCR Signaling Pathways: From Membrane to Nucleus

TCR signaling initiation involves a carefully orchestrated sequence of molecular events that translate extracellular binding into intracellular activation. When a TCR engages an agonist pMHC, the CD4 or CD8 coreceptors recruit the Src family kinase Lck to the TCR complex [1]. Lck then phosphorylates tyrosine residues within the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) on the CD3 and ζ chains [1]. Each ITAM contains two tyrosines that, when phosphorylated, create docking sites for the ζ-chain-associated protein kinase 70 (Zap70) [1].

Zap70, which resides in the cytoplasm in an autoinhibited state prior to TCR engagement, is recruited to the phosphorylated ITAMs where its conformation is disrupted and activated through phosphorylation by Lck [1]. Once activated, Zap70 phosphorylates the linker for activation of T cells (LAT), which serves as a central signaling hub [1]. Phosphorylated LAT recruits several key effectors, including phospholipase Cγ1 (PLCγ1), which is responsible for hydrolyzing phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to generate the second messengers inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) [1]. IP3 triggers calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum and subsequent influx of extracellular calcium, activating proteins such as the transcription factor NFAT, while DAG activates protein kinase C (PKC) and RasGRP, leading to MAP kinase pathway activation and ultimately T cell activation and differentiation [1].

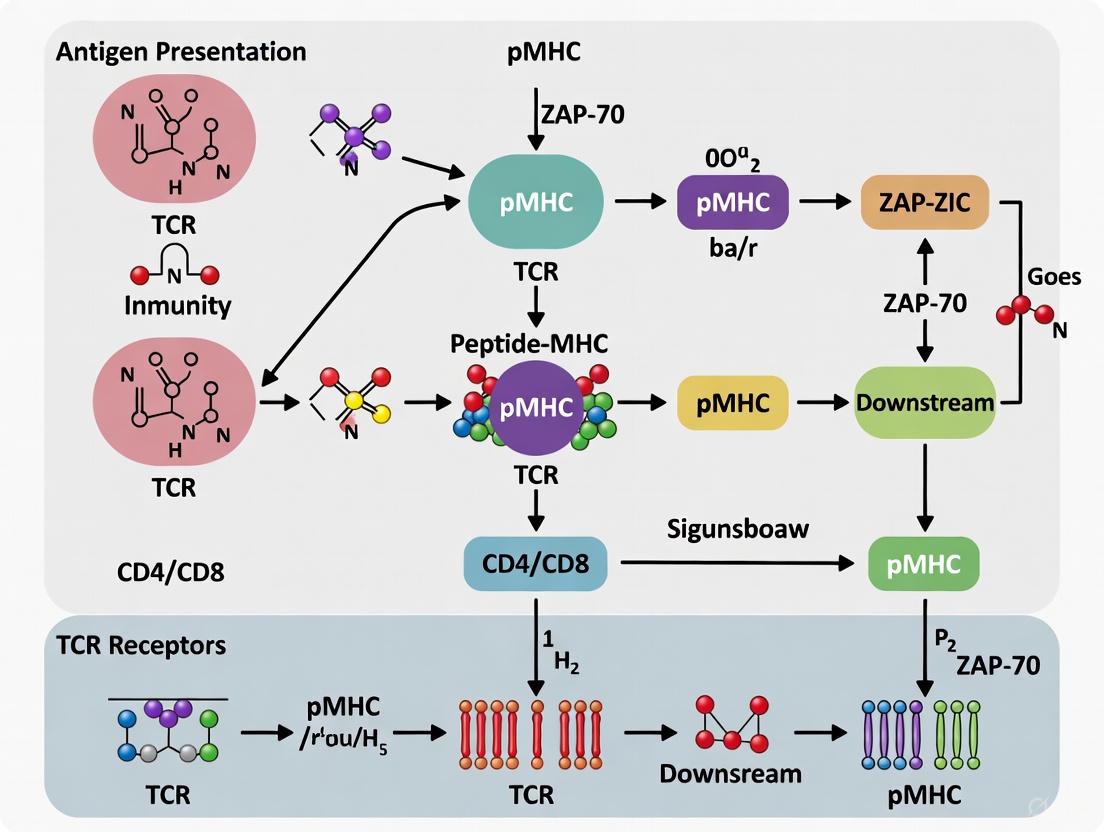

The following diagram illustrates the core TCR signaling pathway:

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as powerful tools for investigating TCR-pMHC interactions at atomic resolution, providing insights that complement structural biology approaches. All-atom MD simulations probe system flexibility by computing iterative solutions of Newton's equations of motion over time, generating trajectories that describe atomic positions throughout the simulation [3]. While computationally demanding and typically limited to microsecond timescales—shorter than biologically relevant seconds-to-minutes signaling timescales—advanced sampling techniques have enhanced their utility [3].

Several specialized MD approaches are particularly valuable for studying TCR-pMHC interactions:

- Replica Exchange MD (REMD): Simulates multiple copies of the same molecule at different temperatures, improving conformational sampling for relatively small systems [3].

- Steered MD (SMD): Applies external force to study mechanical responses, analogous to atomic force microscopy; useful for investigating TCR-pMHC dissociation and catch bond formation [3] [6].

- Coarse-Grained (CG) Methods: Replaces atom groups with beads to enable longer simulations of larger complexes, such as TCR-pMHC in membrane environments [3].

These computational approaches have revealed that mutations to peptides in the MHC binding groove alter MHC conformation at equilibrium and impact TCR-pMHC bond strength under constant load, with physiochemical features such as hydrogen bonds and Lennard-Jones contacts correlating with immunogenic responses [6].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for TCR-pMHC Studies

| Research Tool | Composition/Type | Application and Function |

|---|---|---|

| pMHC Tetramers | Multiple pMHC complexes linked to fluorescent tag [7] | Identification and isolation of antigen-specific T cells via flow cytometry |

| pMHC-Targeted Viruses | Retroviruses pseudotyped with pMHC and fusogen [7] | Antigen-specific gene delivery to CD8+ T cells; simultaneous activation and genetic modification |

| TCR Cloning Reagents | Vectors for TCR α and β chain expression [8] | Generation of TCR-engineered T cells for adoptive immunotherapy |

| Immune Repertoire Databases | IEDB, VDJdb, McPAS-TCR [9] [5] | Catalog experimentally validated TCR-pMHC interactions; training data for predictive algorithms |

| CDR3β-Specific Antibodies | Antibodies targeting variable CDR3 regions [5] | Detection and characterization of specific TCR clonotypes |

TCR Repertoire Analysis

High-throughput sequencing of TCR repertoires has enabled comprehensive characterization of T cell diversity, providing insights into immune responses in health and disease. Key metrics for analyzing TCR repertoire composition include:

- Richness: The number of unique TCR sequences in a sample [8].

- Evenness: The equality in clonal abundances of TCR sequences [8].

- Shannon/Simpson Diversity: Metrics that account for both richness and evenness, with Simpson diversity being particularly sensitive to clonal dominance [8].

- Clonality: A measure of the degree of oligoclonal expansion within a repertoire [8].

These analytical approaches have revealed that tumors can be classified as "hot" or "cold" based on their T cell infiltration, with "hot" tumors (e.g., melanoma, bladder cancer, non-small cell lung cancer) typically showing more favorable responses to immunotherapies [8]. Furthermore, TCR repertoire analysis can guide the selection of TCRs for therapeutic engineering, even when their target antigens remain unknown [8].

Computational Prediction of TCR-pMHC Interactions

Machine learning and deep learning approaches have been increasingly applied to predict TCR-pMHC binding, addressing a critical challenge in immunology. These methods can be broadly categorized into structure-based approaches that utilize TCR-pMHC crystal structures, and sequence-based methods that rely solely on TCR and peptide sequence information [9]. Popular methods include neural networks, convolutional networks, and more recently, transformer-based models and autoencoders [9].

A significant challenge in this domain is data imbalance, as publicly available databases contain far more non-binding TCR-pMHC pairs than confirmed binding pairs [5]. This imbalance can lead to biased predictive models, necessitating specialized approaches such as generative models for data augmentation to restore balance and improve prediction accuracy for rare but biologically important specificities [5].

Therapeutic Applications and Future Directions

The profound understanding of TCR-pMHC interactions has paved the way for groundbreaking immunotherapies, particularly in oncology. Adoptive cell therapy approaches harness the power of T cells redirected to recognize and eliminate cancer cells. While chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have demonstrated remarkable success against hematological malignancies by targeting surface antigens, TCR-engineered T cells offer the distinct advantage of recognizing intracellular antigens presented on MHC molecules, potentially expanding the targetable cancer proteome to include neoantigens and cancer-testis antigens [8].

Recent advances include the development of pMHC-targeted viral vectors that enable in vivo engineering of tumor-specific T cells. These vectors, which display specific pMHC complexes, can selectively transduce and activate cognate T cells while delivering therapeutic transgenes such as immunostimulatory molecules [7]. This approach has demonstrated promising results in immunocompetent mouse models, improving overall survival in B16F10 melanoma-bearing mice while simultaneously activating and expanding antitumor T cells [7].

The future of TCR-pMHC research will likely focus on integrating multidimensional data—including structural information, kinetic parameters, mechanical properties, and repertoire sequencing data—to develop predictive models of T cell activation and function. Such integrated approaches will accelerate the rational design of next-generation immunotherapies with enhanced specificity and efficacy, while minimizing off-target toxicities. As single-cell technologies continue to advance and computational models become increasingly sophisticated, our understanding of the fundamental principles governing TCR-pMHC interactions will deepen, unlocking new possibilities for manipulating the adaptive immune system against cancer, infectious diseases, and autoimmune disorders.

The precise molecular interaction between the T-cell receptor (TCR) and peptide-major histocompatibility complex (pMHC) constitutes the fundamental recognition event in adaptive cellular immunity, governing immune responses to pathogens, cancer, and self-tissues. Understanding the structural basis of this interaction is paramount for advancing TCR-based therapeutics and immunology research. The conserved nature of protein structure provides a significantly less diverse perspective on TCRs and peptides compared to sequence-based approaches, offering potential pathways to overcome the challenge of predicting specificity for unseen pMHC complexes [10]. This technical guide examines the core structural databases and architectural principles that form the foundation of TCR-pMHC research, providing researchers with essential resources and methodologies for structural immunology investigations.

Essential Structural Databases for TCR-pMHC Research

Database Comparisons and Capabilities

Table 1: Core Structural Databases for TCR-pMHC Research

| Database Name | Primary Focus | Key Features | Data Types | Update Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCR3d [11] | TCR structures with antigen recognition focus | TCR docking angles, interface parameters, CDR loop clustering, germline gene usage | Structures, sequences, interface analysis | Weekly updates |

| STCRDab [11] | Structural TCR data | Collection of TCR structural data | Structures, sequences | Active |

| TRAIT [12] | Comprehensive TCR-antigen interactions | Integrates sequences, structures, affinities; includes mutations and clinical trials | Sequences, structures, binding affinities, non-interactive pairs, mutations | Active |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary repository for 3D structural data | Raw experimental structures from X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM, NMR | 3D atomic coordinates | Continuous updates |

| ATLAS [11] | Altered TCR ligand affinities and structures | Links binding affinities with structures for wild-type and mutant TCR-pMHC complexes | Structures, binding affinities | No longer updated after 2017 |

| BATCAVE [13] | TCR cross-reactivity via mutational scans | Database of TCR activation data from mutational scan assays | TCR activation data, peptide mutations, binding affinities | Active |

Specialized Database Features and Applications

The TCR3d database automatically identifies TCR complex structures from the PDB on a weekly basis using hidden Markov models representing TCR variable domain sequences [11]. It provides calculated TCR docking angles based on the approach of Rudolph et al., interface buried surface area using NACCESS, and shape complementarity using Sc from the CCP4 suite [11]. TCR3d's primary interface consists of browsable tables of all TCR-antigen complexes classified by TCR restriction (Class I MHC, Class II MHC, CD1d, MR1), as well as γδ TCRs, containing key features of TCRs and targeting [11].

The recently developed TRAIT database distinguishes itself through comprehensive integration of multiple data types, including millions of experimentally validated TCR-antigen pairs and non-interactive TCR sequences verified by single-cell omics [12]. TRAIT systematically collects binding affinity data measured by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), and uniquely includes mutation data with 641 TCR mutants and 628 antigen mutants, each linked to binding affinity [12]. This integrated approach provides researchers with a holistic view of TCR-antigen interactions.

Experimental Methodologies for Structural Determination

Structural Determination Protocols

X-ray Crystallography Workflow:

- Protein Complex Production: Express and purify TCR, peptide, and MHC components separately

- Complex Formation: Mix components in appropriate molar ratios to form stable TCR-pMHC complexes

- Crystallization: Screen crystallization conditions using vapor diffusion or micro-batch methods

- Data Collection: Collect X-ray diffraction data at synchrotron facilities

- Structure Determination: Solve structure using molecular replacement with existing TCR or MHC structures as search models

- Model Refinement: Iteratively refine the model against diffraction data

The most precise method to dissect TCR-pMHC interactions involves experimentally generating X-ray crystallography structures, though this remains a time-consuming and technically demanding process [14] [15]. As of 2025, approximately 223 TCR-antigen complex structures were available in the PDB according to the TRAIT database [12].

Binding Affinity Measurement: Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) protocols for TCR-pMHC interactions:

- Immobilize pMHC complexes on sensor chips via amine coupling or capture methods

- Flow TCR samples at varying concentrations over immobilized pMHC

- Measure association and dissociation phases to determine kinetic parameters (ka, kd)

- Calculate equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) from kinetic parameters

- Include reference cell subtraction to control for nonspecific binding

Advanced Functional Assays

Recent methodologies incorporate mechanical force considerations into TCR-pMHC interaction analysis. Single-molecule biophysical approaches demonstrate that natural TCRs exploit mechanical force to form optimal catch bonds with cognate antigens, relying on a mechanically flexible TCR-pMHC binding interface [16]. This process enables force-enhanced CD8 coreceptor binding to MHC-α1α2 domains through sequential conformational changes induced by force in both the MHC and CD8 [16].

Mutational scan databases like BATCAVE provide comprehensive experimental data on TCR cross-reactivity, containing continuous-valued TCR activation data for both single- and multi-amino acid peptide mutations [13]. These resources help establish the relationship between peptide sequence variations and TCR responsiveness, addressing critical gaps in negative example data that are essential for model discrimination.

Computational Approaches and AI-Driven Structure Prediction

AlphaFold-Based TCR-pMHC Modeling

AlphaFold 3 (AF3) has demonstrated significant capability in modeling TCR-pMHC interactions, distinguishing valid epitopes from invalid ones with increasing accuracy [14] [15]. The standard AF3 protocol for TCR-pMHC prediction utilizes the model without retraining or fine-tuning, employing default hyperparameters including three cycles of recycling, a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) depth of 256, and a template dropout rate of 15% [14] [15].

Critical findings indicate that peptide presence is essential for accurate TCR-pMHC predictions. AF3 predictions of TCR binding in the presence of peptide-MHC complexes closely mirror crystal structures, while predictions without peptides show significantly reduced accuracy [14] [15]. This is reflected in interface template modeling (ipTM) scores, with presence of peptide resulting in ipTM = 0.92 compared to ipTM = 0.54 without peptide in NY-ESO-1 specific TCR examples [14] [15].

Advanced Structural Analysis pipelines

The NetTCR-struc approach addresses limitations in AlphaFold-Multimer's confidence scoring, which in certain cases correlates poorly with DockQ quality scores, leading to overestimation of model accuracy [10]. Their graph neural network (GNN) solution achieves a 25% increase in Spearman's correlation between predicted quality and DockQ (from 0.681 to 0.855) and improves docking candidate ranking [10].

The structural modeling pipeline involves:

- Feature Generation: Creating MSA and template features with approaches that model pMHC as a single chain

- Perturbation Methods: Applying random mutation in MSA, column-wise MSA mutation, MSA hit masking, and Gaussian noise addition to template coordinates

- Model Selection: Using GNN-based quality scoring to select optimal structural models from multiple predictions

Diagram 1: Structural modeling workflow for TCR-pMHC complexes

Core Architectural Principles of TCR-pMHC Complexes

Structural Organization and Binding Interfaces

The TCR-pMHC complex architecture follows conserved principles across diverse TCR specificities. The TCR variable domains position complementarity determining regions (CDRs) to engage the pMHC surface, with CDR3 loops primarily interacting with the peptide antigen, while CDR1 and CDR2 regions contact the MHC α-helices [12]. This organization allows the hypervariable CDR3 loops, which exhibit exceptional diversity, to determine fine specificity for peptide recognition, while the more conserved CDR1 and CDR2 domains maintain binding orientation to the MHC molecule.

Structural analyses reveal that TCR docking angles relative to the pMHC surface fall within a characteristic range, despite significant sequence diversity [11]. The binding interface typically buries 1,200-2,000 Ų of surface area, with shape complementarity statistics indicating optimized interface packing [11]. These conserved architectural features enable the structural classification of CDR loop conformations, with TCR3d providing clustering of CDR loop structures using backbone φψ conformational distances and affinity propagation [11].

Mechanochemical Properties and CD8 Coreceptor Function

Recent research highlights the critical importance of mechanical properties in TCR-pMHC interactions. Naturally evolved TCRs exhibit mechanically flexible binding interfaces that enable optimal catch bond formation under force, which stabilizes interactions with agonistic pMHCs [16]. This flexibility permits force-induced conformational changes that enhance CD8 coreceptor binding to MHC domains, creating a cooperative mechanism that amplifies antigen discrimination.

Diagram 2: Force-induced enhancement of TCR specificity

Engineering high-affinity TCRs often creates rigid, tightly bound interfaces with cognate pMHCs that prevent the force-induced conformational changes necessary for optimal catch-bond formation [16]. Paradoxically, these high-affinity TCRs can form moderate catch bonds with non-stimulatory pMHCs, leading to off-target cross-reactivity and reduced specificity [16]. This explains why 3D binding affinity alone does not consistently predict TCR specificity and functional effectiveness.

Research Reagent Solutions for TCR-pMHC Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 [14] [15] | TCR-pMHC structure prediction | Trained on >120M protein sequences; models ternary complexes |

| NetTCR-struc [10] | Docking quality assessment | GNN-based DockQ regression; 25% improvement in quality correlation |

| TCRmodel [11] | TCR 3D modeling from sequence | Generates 3D models from TCR sequences |

| BATCAVE [13] | TCR cross-reactivity prediction | Mutational scan database; balanced positive/negative examples |

| CD8 Coreceptor [16] | Mechanochemical studies | Enhances catch bonds; force-sensitive engagement |

| pMHC Mutants [13] | Specificity mapping | Single/multi-aa variants for TCR recognition rules |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance [12] [16] | Binding affinity measurement | Kinetic parameter determination (ka, kd, Kd) |

The structural foundations of TCR-pMHC research continue to evolve with advancing database technologies, experimental methodologies, and computational approaches. Integration of structural data with binding affinities, mutational scans, and functional outcomes provides increasingly comprehensive understanding of the molecular determinants of TCR specificity. Future directions include improving zero-shot prediction capabilities for novel TCR-pMHC pairs, enhancing understanding of the role of mechanical forces in immune recognition, and developing more accurate models for predicting immunogenicity and cross-reactivity. The continued development of integrated databases like TRAIT that combine sequences, structures, affinities, and clinical annotations will further accelerate therapeutic applications in T-cell-based immunotherapies.

The recognition of peptide-major histocompatibility complexes (pMHC) by T-cell receptors (TCR) represents a fundamental interaction in adaptive immunity. While historically characterized by binding affinity (ΔG), emerging research demonstrates that a comprehensive understanding of TCR-pMHC interactions requires integration of thermodynamic, kinetic, and mechanical perspectives. This whitepaper synthesizes current findings revealing how enthalpy-entropy compensation governs binding thermodynamics, how two-dimensional kinetics more accurately predict T-cell responsiveness than three-dimensional measurements, and how mechanical forces and allosteric mechanisms regulate signal propagation. The integration of these dimensions provides a refined framework for predicting T cell specificity and developing novel immunotherapies.

T cell receptors initiate adaptive immune responses through specific engagement with peptide-MHC complexes, an interaction characterized by remarkable sensitivity and discrimination. While earlier research focused primarily on binding affinity, contemporary studies reveal this approach provides an incomplete picture. The TCR-pMHC interaction occurs in a complex two-dimensional membrane environment where mechanical forces and dynamic kinetics play crucial roles in determining functional outcomes [3] [17]. This review examines the integrated roles of thermodynamics, kinetics, and mechanics in shaping TCR signaling, highlighting how these dimensions collectively enable T cells to discriminate between self and non-self antigens with extraordinary fidelity, and how this understanding informs therapeutic development in immunotherapy.

Core Principles: The Triad of TCR-pMHC Recognition

Thermodynamic Compensation and Conformational Flexibility

The thermodynamics of TCR-pMHC binding defies simple characterization. Isothermal titration calorimetry and van't Hoff analyses reveal no universal thermodynamic signature for TCR recognition, with substantial diversity in enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) changes across different TCR-pMHC pairs [18]. Rather, these parameters exhibit compensatory variation, maintaining binding free energy (ΔG) within a narrow window despite considerable interface diversity [18].

Table 1: Thermodynamic Parameters of Representative TCR-pMHC Interactions

| TCR | pMHC | ΔH (kcal/mol) | -TΔS (kcal/mol) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | Conformational Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JM22 | HLA-A2-M1 | Favorable | Unfavorable | ~ -7 to -10 | CDR loop reorganization |

| F5 | HLA-A2-M1 | Favorable | Unfavorable | ~ -7 to -10 | CDR loop reorganization |

| A6 | HLA-A2-Tax | Variable | Compensatory | ~ -7 to -10 | CDR loop flexibility |

| LC13 | HLA-B8-FLR | Variable | Compensatory | ~ -7 to -10 | CDR loop flexibility |

This enthalpy-entropy compensation reflects underlying conformational dynamics within TCR complementarity-determining region (CDR) loops. Early assumptions that unfavorable binding entropy universally indicated conformational flexibility loss have been challenged by observations of entropically favorable TCR-pMHC interactions [18]. Structural analyses indicate that TCR CDR loops frequently populate different conformations in free versus bound states, with this pre-existing flexibility enabling TCRs to engage diverse pMHC ligands [18].

Kinetic Parameters in Two versus Three Dimensions

The cellular context of TCR-pMHC interactions necessitates distinction between solution-based (3D) and membrane-anchored (2D) kinetics. Remarkably, 2D measurements reveal kinetic parameters with dramatically expanded dynamic ranges that better correlate with T-cell responsiveness compared to their 3D counterparts [17].

Table 2: Comparison of 2D and 3D Kinetic Parameters for OT1 TCR

| Peptide | Activation Profile | 2D AcKa (μmâ´) | 2D koff (sâ»Â¹) | 3D KD (μM) | 3D koff (sâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OVA | Antigen | 2.4 × 10â»â´ | 7.2 | ~1-10 | 0.01-0.1 |

| A2 | Agonist | 2.8 × 10â»â´ | 3.3 | ~1-10 | 0.01-0.1 |

| G4 | Weak agonist/antagonist | 1.4 × 10â»âµ | 3.4 | ~100 | ~1 |

| R4 | Antagonist | 1.1 × 10â»â¶ | 1.8 | >100 | >1 |

Critical differences emerge from this comparison: 2D affinities for agonist pMHCs are significantly higher than 3D measurements suggest, and 2D off-rates are up to 8,300-fold faster than 3D off-rates, with agonist pMHCs dissociating most rapidly [17]. This indicates that T cells employ rapid antigen sampling in physiological conditions, with the broadest discrimination achieved through 2D on-rates (Ackon) spanning five orders of magnitude [17].

Mechanical Regulation and Allosteric Signaling

Forces in the range of 10-20 pN generated during T cell-APC conjugation introduce critical mechanical components to TCR recognition [19]. Recent models propose that TCRs function as allosteric mechanosensors, where pMHC binding induces conformational changes transmitted to CD3 components through the TCRβ subunit [4].

Molecular dynamics simulations of complete TCR-CD3-pMHC complexes reveal that pMHC engagement shifts the TCR extracellular domain from bent (104°) to extended (150°) conformations, reducing contacts between TCRβ variable domain and CD3εγ dimer [4]. This conformational rearrangement increases CD3 mobility, potentially facilitating ITAM phosphorylation by releasing spatial constraints on CD3 cytoplasmic domains [4].

Diagram 1: TCR Mechanosensing Pathway

Simulations further demonstrate that peptide identity alters MHC binding groove conformation, influencing TCR-pMHC bond stability under force [19]. Agonist peptides promote bond lifetimes through specific hydrogen bond and hydrophobic contact patterns that persist under physiological loads (10-20 pN), providing a mechanical proofreading mechanism for antigen discrimination [19].

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies for Multidimensional Analysis

Thermodynamic Measurement Techniques

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) provides direct measurement of binding enthalpy (ΔH), stoichiometry (n), and association constant (Ka) through incremental injections of one binding partner into another while measuring heat changes. When combined with van't Hoff analysis across multiple temperatures, ITC enables determination of heat capacity changes (ΔCp) and decomposition of free energy into enthalpic and entropic components [18]. For TCR-pMHC systems, these measurements reveal the substantial enthalpic-entropic compensation governing interactions, though care must be taken to account for linked protonation equilibria and buffer effects that can complicate interpretation [18].

Two-Dimensional Binding Assays

Micropipette Adhesion Frequency Assay utilizes a red blood cell (RBC) functionalized with pMHC monomers as an adhesion sensor. A T cell is manipulated to repeatedly contact the RBC with controlled contact area and duration, with adhesion events detected by RBC membrane elongation upon retraction [17]. Measuring adhesion frequency (Pa) across varying contact times (tc) enables extraction of 2D kinetic parameters through fitting with a probabilistic model: Pa = 1 - exp(-mrmlAcKa(1 - e^(-koff*tc))) where mr and ml are receptor and ligand densities, Ac is contact area, Ka is 2D affinity, and koff is off-rate [17].

Biomembrane Force Probe (BFP) Thermal Fluctuation Assay employs a RBC and bead system with enhanced sensitivity to detect single bond formation and dissociation events through monitoring bead position fluctuations [17]. Bond formation restricts bead movement, enabling direct measurement of bond lifetime distributions and confirmation of first-order dissociation kinetics through exponential decay fitting [17].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

All-Atom Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations compute Newton's equations of motion for TCR-pMHC-CD3 systems embedded in lipid bilayers, typically using CHARMM36 or similar force fields [20] [19]. These simulations reveal atomic-scale interactions and conformational dynamics on microsecond timescales, though this remains shorter than biologically relevant signaling timescales [3].

Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) applies external forces to simulate mechanical loading on TCR-pMHC bonds, mimicking physiological forces (10-20 pN) experienced at the immune synapse [19]. Multi-replicate SMD simulations quantify force-dependent bond lifetimes and identify critical hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts that stabilize interactions under load [19].

Essential Dynamics (Principal Component Analysis) reduces trajectory complexity by identifying collective atomic motions corresponding to largest positional fluctuations, distinguishing key conformational changes from irrelevant background vibrations [20].

Diagram 2: Computational Workflow

Kinetic Proofreading Models

Sequential Proofreading models propose TCR signaling requires progression through sequential biochemical steps (ITAM phosphorylation, ZAP70 recruitment, etc.), with rapid ligand dissociation terminating the process [21]. This model predicts signaling probability proportional to (kp/(kp + koff))^n where kp is forward rate, koff is dissociation rate, and n is step number [21].

Multithread Proofreading incorporates ITAM multiplicity, with parallel reaction threads on ten TCR-CD3 ITAMs integrated through LAT condensation [21]. This model significantly enhances discrimination fidelity by multiplying effective proofreading steps without requiring fine-tuned kinetic parameters for chemically distinct reactions [21].

Integrated Signaling Model: From Binding to Functional Response

The integration of thermodynamic, kinetic, and mechanical perspectives yields a coherent model of TCR triggering. Initial pMHC binding, governed by 2D on-rates and conformational selection, induces extended TCR conformation that increases CD3 mobility [4]. Mechanical forces stabilize agonist bonds through specific interaction patterns, enabling phosphorylation of multiple ITAM domains [19] [21]. Parallel proofreading threads integrate through LAT condensation, producing digital signaling outputs that discriminate agonists based on bond lifetime under force [21].

This multithreaded proofreading explains how T cells achieve high fidelity discrimination despite small dwell time differences (~10-fold) between agonist and self-pMHCs amid large abundance differences (>1,000-fold) [21]. The combination of multiple ITAM threads with LAT condensation creates a robust proofreading mechanism that amplifies discrimination capacity while maintaining sensitivity to rare agonist ligands [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for TCR-pMHC Studies

| Reagent / Method | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Soluble TCR/pMHC Ectodomains | Binding studies | Enables thermodynamic and 3D kinetic measurements |

| Streptavidin-based pMHC Tetramers | T cell staining | Multivalent presentation for flow cytometry |

| Di-streptavidin (Di-SA) | Monomeric pMHC presentation | Ensures 1:1 binding in 2D assays [17] |

| Micropipette Adhesion Assay | 2D kinetics | Measures low-affinity interactions in membrane context [17] |

| Biomembrane Force Probe (BFP) | Single-bond kinetics | Detects individual bond formation/dissociation [17] |

| CHARMM36 Force Field | MD simulations | All-atom parameters for membrane-protein systems [20] [19] |

| Coarse-Grained MD | Longer timescales | Reduced complexity for large assembly dynamics [3] |

The multidimensional perspective on TCR-pMHC recognition reveals why affinity-based models alone fail to predict T cell responsiveness accurately. The integration of thermodynamic compensation, expanded 2D kinetic discrimination, and mechanical regulation provides a more comprehensive framework for understanding T cell specificity. These insights are already informing therapeutic design, with engineered TCRs incorporating kinetic and mechanical optimization alongside affinity enhancement [19] [22]. Future research should further elucidate allosteric communication pathways and develop integrated models that simultaneously incorporate thermodynamic, kinetic, and mechanical parameters to predict T cell responses across diverse biological contexts.

The adaptive immune system of higher chordates faces a formidable challenge: it must reliably distinguish between self and non-self-antigens to provide protection without provoking autoimmunity. Central to this capability is the interaction between the T-cell receptor (TCR) and peptide-bound major histocompatibility complex (pMHC). This interaction exhibits a paradoxical combination of extreme sensitivity and remarkable specificity, enabling T cells to detect even a single foreign pMHC among thousands of structurally similar self-ligands [2] [23]. The kinetic proofreading model provides a robust theoretical framework to explain this extraordinary discriminatory capability. Originally proposed to explain fidelity in biomolecular processes such as protein synthesis, this model has been successfully adapted to T cell signaling, where it explains how small differences in binding dwell times can be amplified into all-or-nothing activation decisions [2] [24] [25]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding kinetic proofreading is essential for advancing immunotherapies, including the engineering of chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) and TCR-engineered T cells, where optimal signaling architectures must balance sensitivity with specificity to maximize therapeutic efficacy and minimize off-target effects [2].

Core Principles of the Kinetic Proofreading Model

Thermodynamic Limitations of Affinity-Based Discrimination

The most intuitive parameter for assessing TCR-pMHC interaction specificity is affinity, a thermodynamic characteristic representing binding strength. Affinity is expressed as the association constant (Kâ‚), which is the ratio of the association (kâ‚’â‚™) and dissociation (kâ‚’ff) rate constants [2]. The underlying assumption is that complementarity between TCR and pMHC drives discrimination, where the free energy (ΔG) of binding determines specificity [2]. However, the difference in free energy between correct (agonist) and incorrect (self) pMHC ligands is often insignificant or absent, severely limiting the explanatory power of purely affinity-based models [2]. This paradox mirrors other biological processes; during protein synthesis, for example, the difference in free energy between correct and incorrect codon-anticodon pairs is too small to account for the observed error rate of approximately 1 in 20,000 [2]. This fundamental limitation prompted the development of models that incorporate the kinetic dimensions of molecular interactions.

The Kinetic Proofreading Solution

The kinetic proofreading model, initially proposed by Hopfield and Ninio, resolves this paradox by accounting for the multistage nature of ligand-receptor interactions [2] [25]. The model posits that a series of irreversible, energy-consuming steps occur after the initial ligand binding. Each step acts as a verification point, increasing the overall specificity of the process [2]. In the context of TCR-pMHC interactions, this means that for a signaling outcome to be triggered, the ligand must remain bound long enough for the receptor to progress through a sequence of intermediate biochemical steps, such as phosphorylation events [2] [24]. If the ligand dissociates at any point before completion of this sequence, the process is aborted, and no signal is produced [24]. This mechanism allows the system to discriminate based on ligand residence time (Ï„ = 1/kâ‚’ff), rather than binding affinity alone [2]. Consequently, a ligand with a longer dwell time has a exponentially higher probability of completing the proofreading chain and triggering T cell activation [2].

Table 1: Key Parameters in TCR-pMHC Interaction Models

| Parameter | Definition | Role in Specificity | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity (Kâ‚) | Thermodynamic binding strength (kâ‚’â‚™/kâ‚’ff) | Determines initial binding probability | Poor at discriminating small free energy differences |

| Residence Time (Ï„) | Lifetime of the TCR-pMHC complex (1/kâ‚’ff) | Determines probability of completing proofreading steps | Does not account for mechanical and spatial context |

| Kinetic Selectivity (Sâ‚–) | Ratio of association rates for competing ligands (kâ‚’â‚™pMHC1/kâ‚’â‚™pMHC2) | Provides kinetic dimension to discrimination | Highly dependent on experimental conditions |

| Proofreading Steps (n) | Number of irreversible intermediate steps | Amplifies discrimination; fidelity increases with n | Requires finely tuned kinetics in sequential models |

From Sequential to Multithreaded Proofreading: Evolving Models

Traditional kinetic proofreading models have conceptualized the process as a linear, sequential Markov process [21]. Upon ligand binding, the TCR progresses through a series of 'proofreading steps' (such as ITAM phosphorylation and ZAP70 recruitment) before reaching a signaling-active state [21]. The number of steps is a key determinant of discrimination fidelity in this model. However, this sequential scheme faces physical implementation challenges, as it requires multiple chemically distinct reactions to have finely matched kinetics to be effective [21].

Recent research has revealed that the molecular mechanism of TCR activation diverges significantly from a simple sequential process. A groundbreaking 2025 study proposes a "multithread" kinetic proofreading scheme that incorporates two key features of TCR biology [21]:

- ITAM Multiplicity: The TCR:CD3 complex contains ten immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) domains in its cytoplasmic tails, each capable of recruiting and activating a ZAP70 molecule. These represent parallel reaction sequences initiated on a single ligated TCR [21].

- LAT Condensation: The outputs from multiple ITAM threads are integrated into a binary, all-or-nothing output through the formation of a LAT condensate, which serves as a quantal signaling unit [21].

In this revised model, multiple parallel reaction threads (corresponding to individual ITAM domains) are synchronously initiated upon TCR engagement. These threads progress independently, and their outputs are reintegrated at the LAT condensation step [21]. This architecture dramatically improves discrimination fidelity by nearly multiplying the effective number of proofreading steps by the number of parallel threads. Since the threads are chemically identical copies, their kinetics are intrinsically uniform, overcoming a major hurdle of the sequential model [21]. This suggests that ITAM multiplicity, rather than a long chain of sequential steps, may be the primary source of proofreading fidelity in T cells [21].

Quantitative Analysis of Proofreading Fidelity

The performance of kinetic proofreading models can be quantitatively assessed by their ability to discriminate between agonist and self-ligands based on dwell times. The discrimination fidelity is defined as the ratio of the signaling probability for an agonist ligand to that of a self-ligand [21]. Computational comparisons between sequential and multithread schemes reveal distinct performance characteristics.

In a sequential scheme with n steps, the probability that a ligand with dwell time t completes all steps and produces a signal is proportional to (kâ‚št)â¿, where kâ‚š is the rate of progression through each step [21]. This relationship creates an exponentially steep dependence on dwell time. However, if the individual steps have heterogeneous rates, the slowest step (the rate-limiting step) dominates, effectively reducing the number of productive proofreading steps [21]. For instance, a 10-step sequential reaction with 20-fold rate heterogeneity provides only about three effective proofreading steps [21].

In contrast, the multithread scheme with m threads, each consisting of n steps, can achieve a fidelity similar to a sequential scheme with n × m steps [21]. The parallelism provided by multiple identical ITAM domains relieves the need for fine-tuned kinetics among chemically distinct reactions. This makes the multithread scheme a more evolutionarily accessible and robust solution for achieving high-fidelity antigen discrimination [21]. Mechanistically, this implies that as few as one rate-limiting step occurring on several ITAMs may be sufficient to describe the experimentally measured antigen discrimination fidelity of T cells [21].

Table 2: Comparison of Sequential vs. Multithread Proofreading Models

| Feature | Sequential Model | Multithread Model |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Linear sequence of n steps |

m parallel threads, each with n steps, integrated at output |

| Key Determinant of Fidelity | Number of steps (n) |

Number of threads (m) × steps per thread (n) |

| Kinetic Requirement | Finely matched rates for distinct chemical reactions | Intrinsically uniform rates across identical threads |

| Physical Basis | Hypothetical sequence of distinct biochemical events | ITAM multiplicity and LAT condensation |

| Robustness to Rate Heterogeneity | Low; slowest step dominates | High; parallelism mitigates single-step limitations |

| Effective Number of Steps | Limited by rate-limiting step | Multiplied by thread count |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Quantifying Molecular Forces in the Immunological Synapse

Mechanical forces have been implicated in T cell antigen recognition and ligand discrimination, yet their magnitude, frequency, and impact remain debated. A 2025 study quantitatively assessed forces across various TCR:pMHC pairs using a Molecular Force Sensor (MFS) platform at single-molecule resolution [23]. The experimental workflow is as follows:

- Sensor Construction: A FRET-based molecular force sensor is constructed using a peptide backbone from flagelliform spider silk protein. Two fluorophores constituting a FRET pair are attached to this entropic spring. The sensor is conjugated to the base of a pMHC ligand [23].

- Platform Preparation: The pMHC-conjugated MFS is anchored to a glass-supported lipid bilayer (SLB), which is also decorated with adhesion molecules (ICAM-1) and costimulatory molecules (B7-1) to mimic an antigen-presenting cell [23].

- Microscopy and Data Acquisition: T cells are introduced to the SLB under either scanning conditions (low MFS density, no activation) or activating conditions (high density of unlabeled stimulatory pMHC). Single-molecule time traces of FRET donor and acceptor molecules are recorded using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy with alternating laser excitation [23].

- Force Analysis: In the absence of force, the sensor is collapsed, resulting in high FRET efficiency. Force application extends the spring, increasing the inter-dye distance and reducing FRET yield. A FRET efficiency threshold is established from cell-free measurements, and data points below this threshold are classified as the "high-force fraction" [23]. Force probability density functions are estimated by comparing FRET efficiency distributions with and without T cell contact [23].

This methodology revealed that CD4+ T cells exert significantly lower forces on TCR:pMHC bonds than previously estimated, with only a small fraction of engaged TCRs subjected to measurable forces. Furthermore, these rare, minute forces did not impact the global lifetime distribution of the TCR:ligand bond, suggesting that the immunological synapse may function as a "force-shielded" environment to ensure stable antigen recognition [23].

Computational Modeling of Proofreading Schemes

Computational models are indispensable for comparing the performance of different proofreading architectures. The following methodology is used to simulate and compare sequential and multithread schemes:

- Sequential Scheme Modeling: The ligated receptor is modeled as progressing through

nreaction steps with a forward ratekâ‚š. Ligand unbinding can occur at any time with an off-ratek. A signal is produced only if the final step is reached before unbinding [21]. - Multithread Scheme Modeling: Upon ligand binding,

mindependent reaction threads (representing ITAM domains) are synchronously initiated. Each thread progresses throughnsteps with ratekâ‚š. The state of the receptor is the ensemble of all thread states. The firing rate for the binary output (representing LAT condensation) is a function of the number of completed threads [21]. - Stochastic Simulation: Both schemes are implemented in a stochastic setting (e.g., using Gillespie algorithms) to account for the inherent randomness of biochemical reactions, especially given the low numbers of agonist pMHCs involved in real T cell activation [21].

- Performance Evaluation: The signaling probability is computed for ligands with different dwell times (e.g., agonist vs. self-pMHC). The discrimination fidelity is calculated as the ratio of these probabilities. The performance is analyzed as a function of the number of steps (

n), number of threads (m), and heterogeneity in reaction rates [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating TCR Kinetic Proofreading

| Reagent / Tool | Function/Description | Application in Proofreading Research |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Force Sensors (MFS) | FRET-based peptide spring conjugated to pMHC; quantifies piconewton-scale forces. | Direct measurement of TCR-imposed mechanical forces within the synapse [23]. |

| Glass-Supported Lipid Bilayers (SLB) | Synthetic membrane system presenting mobile pMHC, adhesion, and costimulatory ligands. | Reconstitution of a controllable APC surface for live-cell TIRF microscopy [23]. |

| TIRF Microscopy | Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence microscopy. | High-resolution, single-molecule imaging of events at the T cell-SLB interface [23]. |

| ePytope-TCR Framework | A unified computational framework integrating 21 pre-trained TCR-epitope prediction models. | Benchmarking and applying machine learning models to predict TCR-pMHC binding [26]. |

| ITAM Mutant TCRs | TCR constructs with mutated immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs. | Dissecting the role of ITAM multiplicity and parallel processing in proofreading [21]. |

| LAT Condensation Reporters | Fluorescent reporters for visualizing the formation of LAT signaling condensates. | Monitoring the binary, quantal output of TCR signaling as an endpoint for proofreading [21]. |

| F-PEG2-S-Boc | F-PEG2-S-Boc|PEG Linker|For Research Use | F-PEG2-S-Boc is a heterobifunctional PEG linker with fluorine and Boc-protected amine termini. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Apoptosis inducer 9 | Apoptosis inducer 9, MF:C34H55N3O4S, MW:601.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Kinetic Proofreading Mechanisms

Sequential Proofreading Scheme

Diagram 1: Sequential proofreading model with N steps.

Multithread Proofreading Scheme

Diagram 2: Multithread proofreading with LAT integration.

Molecular Force Sensor Workflow

Diagram 3: Molecular force sensor operation principle.

The kinetic proofreading model provides a powerful conceptual and quantitative framework for understanding the exquisite specificity of T cell antigen recognition. The evolution of this model from a simple sequential cascade to a sophisticated multithreaded system reflects our growing appreciation of the complexity of TCR signaling. The incorporation of ITAM multiplicity and LAT condensation offers a more plausible and robust mechanistic basis for the observed fidelity of antigen discrimination, resolving key physical implementation challenges of purely sequential models [21]. Furthermore, advanced experimental techniques, such as single-molecule force spectroscopy, are refining our understanding of the biophysical context in which proofreading occurs, suggesting that the immunological synapse may be designed to minimize mechanical perturbations rather than rely on them [23].

For translational research and drug development, these insights are critical. Engineering next-generation CAR-T cells or TCR-engineered T cells could benefit from incorporating design principles inspired by the multithreaded proofreading architecture, such as multiple independent signaling domains, to enhance specificity and reduce off-target activation [2] [21]. Meanwhile, computational prediction tools for TCR-epitope specificity, while rapidly advancing, still face challenges in generalizing to unseen epitopes and overcoming dataset biases [26] [27]. Future work integrating quantitative biophysical parameters, such as binding kinetics and force sensitivity, with sequence-based machine learning models may lead to more accurate predictions and accelerate the development of safer, more effective T cell-based therapies.

T-cell cross-reactivity, the ability of a single T-cell receptor (TCR) to recognize multiple peptide-MHC (pMHC) complexes, represents a fundamental immunological paradox. From an evolutionary perspective, this phenomenon is essential for providing heterologous immunity between pathogens and maximizing the antigenic coverage of a limited TCR repertoire. However, in the context of T-cell-based immunotherapies, this same biological feature becomes a significant therapeutic liability, potentially leading to severe off-target toxicities. This whitepaper examines the dual nature of T-cell cross-reactivity through the lens of adaptive cellular immunity principles and TCR-pMHC interaction research, synthesizing recent advances in computational prediction, structural biology, and clinical validation. By integrating mechanistic insights with emerging mitigation strategies, we provide a framework for leveraging cross-reactivity's benefits while minimizing its risks in therapeutic development.

The adaptive immune system faces a formidable challenge: deploying a finite repertoire of T-cell receptors—estimated at 10¹ⵠunique specificities—to recognize a virtually infinite universe of potential antigens [28]. Cross-reactivity resolves this fundamental constraint through molecular mimicry, enabling individual TCRs to engage multiple structurally similar pMHC complexes. This biological imperative provides crucial heterologous immunity between pathogens, allowing pre-existing memory T cells to respond to novel infections [29].

Paradoxically, this same mechanism underpins significant clinical risks in immunotherapy. The most notable example occurred in a melanoma trial where MAGEA3-specific engineered T-cells cross-reacted with a TITIN-derived peptide expressed in cardiac tissue, causing lethal cardiotoxicity [29]. This tragedy underscored cross-reactivity's therapeutic liability and ignited efforts to predict and prevent such events.

Understanding cross-reactivity requires examining TCR-pMHC interactions at atomic resolution. The binding interface involves complementarity-determining regions (CDRs), with CDR3 exhibiting the highest variability and playing a crucial role in epitope recognition [28]. Cross-reactivity emerges when biophysical similarities enable a single TCR to engage multiple peptides, often through shared structural motifs or TCR hotspots [29].

Computational Approaches for Predicting Cross-reactivity

AI/ML-Enabled Structural Prediction

Recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence have revolutionized TCR-pMHC interaction modeling. AlphaFold 3 (AF3) demonstrates remarkable accuracy in predicting TCR-pMHC complexes by leveraging deep neural networks trained on over 120 million protein sequences and 2.2 million experimental structures [14]. As shown in Table 1, AF3's predictive performance significantly depends on peptide presence, with interface template modeling (ipTM) scores dropping from 0.92 with peptides to 0.54 without peptides (p-value = 6e-04) [14].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Computational Tools for TCR-pMHC Prediction

| Tool | Approach | Key Features | Performance Metrics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 [14] | Structural prediction | Deep neural networks, ipTM scoring | ipTM = 0.92 with peptide vs. 0.54 without | Overestimates model accuracy in some cases |

| CrossDome [29] | Multi-omics toxicity prediction | Peptide-centered & TCR-centered protocols | 82% enrichment with TCR-centered approach | Relies on HLA-binding prediction algorithms |

| TRAP [28] | Contrastive learning | Structural & sequence feature alignment | AUC=0.92 (random), AUC=0.75 (unseen epitopes) | Limited to CDR3β and epitope sequences |

| NetTCR-struc [10] | Graph neural network | DockQ quality scoring | 25% increase in Spearman's correlation | Struggles with low-quality structural models |

| TCR-TRANSLATE [30] | Sequence-to-sequence generation | Adapts machine translation techniques | Successfully designed functional TCR against novel target | Generates polyspecific TCR sequences |

The TRAP framework introduces contrastive learning to enhance generalizability to unseen epitopes, achieving an AUC of 0.75 in challenging unseen epitope scenarios—almost 11% higher than the second-best model [28]. This approach aligns structural and sequence features of pMHC with TCR sequences, addressing a critical limitation in previous models that suffered performance declines when encountering novel epitopes.

Cross-reactivity Specific Prediction Tools

CrossDome represents a specialized approach for predicting off-target toxicity risk, offering both peptide-centered and TCR-centered prediction protocols [29]. In validation studies using 16 known cross-reactivity cases, the TCR-centered approach demonstrated 82% enrichment of validated cases among the top 50 best-scored peptides, substantially improving upon the peptide-centered protocol (63%) [29]. The tool employs a penalty system based on TCR hotspots (contact map) to refine predictions, moving the TITIN-derived peptide from 27th to 6th position out of 36,000 ranked candidates in the MAGEA3 screening [29].

Experimental Validation and Mechanistic Insights

Structural Workflows for TCR-pMHC Modeling

Accurate structural modeling requires sophisticated computational pipelines. NetTCR-struc utilizes an AlphaFold-Multimer-based approach with modified feature generation: template features for pMHC are generated as a single chain to enable use of docked pMHC templates, while TCR multiple sequence alignment (MSA) and template features are generated from a reduced database of immunoglobulin proteins [10]. The pipeline incorporates MSA and template perturbation methods—including random mutation, column-wise mutation, MSA masking, and Gaussian noise addition to template coordinates—to increase modeling diversity [10].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Assessing Cross-reactivity

| Method | Application | Key Measurements | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray crystallography [14] | Structure determination | Atomic coordinates, binding interfaces | High resolution reference data | Time-consuming, technically demanding |

| Molecular Force Sensor (MFS) [23] | Force quantification | FRET efficiency, force probability density | Single-molecule resolution in near-physiological conditions | Technically challenging, low throughput |

| Basophil Activation Test (BAT) [31] | Functional response | CD63 expression on basophils | Direct functional readout | Limited to IgE-mediated reactions |

| Alanine/X-scans [29] | Epitope mapping | Residue contribution to binding | Identifies critical interaction residues | Does not directly identify off-targets |

Diagram 1: Molecular Force Sensor Workflow for Quantifying TCR-Imposed Forces

Biophysical Characterization of TCR-pMHC Interactions

Single-molecule force measurements using Molecular Force Sensor (MFS) platforms reveal that CD4+ T-cells experience significantly lower forces than previously estimated, with only a small fraction of ligand-engaged TCRs subjected to mechanical forces during antigen scanning [23]. These rare, minute forces (median <2 pN on fluid-phase bilayers) do not impact global TCR:ligand bond lifetime distributions, suggesting the immunological synapse creates a biophysically stable environment that prevents pulling forces from disturbing antigen recognition [23].

Surprisingly, binding affinity does not correlate with TCR-imposed mechanical forces across different TCR-pMHC pairs, challenging conventional models of force-dependent binding enhancement [23]. This has important implications for understanding cross-reactivity, as it suggests that structural complementarity rather than binding strength per se may dominate cross-reactive recognition.

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Applications

Risks in T-cell-Based Immunotherapies

Cross-reactivity presents significant safety challenges across multiple immunotherapy modalities, including engineered TCR therapies, adoptive T-cell transfer with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, peptide-based vaccines, and TCR-mimic antibodies [29]. The MAGEA3-TITIN case exemplifies how molecular mimicry between tumor and healthy tissue antigens can lead to on-target, off-tumor toxicity, with fatal consequences [29]. Similar cross-reactivity events have been reported with other tumor-associated antigens, including MART-1, NY-ESO-1, and AFP [29].

Mitigation Strategies and Safety Engineering

Emerging computational tools enable proactive risk assessment during therapeutic development. CrossDome's toxicity prediction leverages multi-omics data integration, combining sequence analysis with expression data from healthy tissues to identify potential off-target peptides [29]. Similarly, TRAP demonstrates capability to diagnose potential cross-reactivity issues between TCRs and similar epitopes, providing a screening mechanism for identifying problematic cross-reactive TCRs before clinical application [28].

TCR-TRANSLATE represents a forward-looking approach for generating antigen-specific TCR sequences against unseen epitopes [30]. However, the framework faces challenges with polyspecific TCR generation, as multitask models preferentially sample CDR3β sequences with reactivity to multiple unrelated peptides [30]. This highlights the tension between generating broadly reactive TCRs and ensuring specificity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for TCR-pMHC Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold-Multimer [14] [10] | TCR-pMHC structure prediction | Complex modeling, interface analysis | ipTM scoring, MSA integration |

| CrossDome R package [29] | Off-target toxicity prediction | Therapy safety assessment | Peptide-centered and TCR-centered protocols |

| Molecular Force Sensors [23] | Single-molecule force measurement | Biophysical characterization | FRET-based, pN resolution |

| TRAP framework [28] | TCR-pMHC binding prediction | Cross-reactivity diagnosis | Contrastive learning, structural features |

| TCR-TRANSLATE [30] | TCR sequence generation | Novel TCR design | Sequence-to-sequence modeling |

| GLP-1R agonist 17 | GLP-1R agonist 17, MF:C28H26ClFN4O4S, MW:569.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Resolvin E1-d4-1 | Resolvin E1-d4-1, MF:C20H30O5, MW:354.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Cross-reactivity embodies a fundamental trade-off in adaptive immunity: the evolutionary advantage of maximal pathogen recognition versus the therapeutic requirement for precise target specificity. This duality necessitates a sophisticated approach that respects cross-reactivity's biological importance while developing strategies to mitigate its risks.

The integration of AI-driven structural prediction with experimental validation creates a powerful framework for advancing the field. Tools like AlphaFold 3 and CrossDome provide unprecedented capability to model and predict cross-reactive potential, while single-molecule techniques like MFS offer mechanistic insights into the biophysical principles governing TCR-pMHC interactions.

For therapeutic development, the path forward lies in embracing cross-reactivity as a design constraint rather than an obstacle. This requires developing comprehensive safety assessment protocols that leverage computational prediction, multi-omics data integration, and rigorous experimental validation. By applying these principles, researchers can harness the evolutionary power of cross-reactivity while ensuring the safety and efficacy of T-cell-based immunotherapies.

As the field progresses, the ultimate goal remains the development of intelligent design principles that achieve the ideal balance: preserving the protective benefits of cross-reactivity while eliminating its dangerous consequences—truly transforming liability back into feature.

The interaction between the T cell receptor (TCR) and peptide-major histocompatibility complex (pMHC) is a cornerstone of adaptive cellular immunity. While traditionally viewed as a reversible, noncovalent binding event, recent research has uncovered that covalent TCR-pMHC interactions represent a potent and physiologically relevant mechanism. These interactions, mediated by disulfide bonds between complementary cysteine residues on the TCR and its peptide antigen, induce exceptionally strong TCR signaling that profoundly alters T cell fate decisions during thymic development. This whitepaper examines the mechanisms, functional consequences, and methodological approaches for studying these unconventional interactions, providing a framework for their potential application in basic immunology and immunotherapy development.

Conventional TCR-pMHC interactions are characterized by moderate affinity and rapid dissociation kinetics, enabling T cells to efficiently scan antigen-presenting cells while maintaining specificity. This paradigm has been enriched by the discovery that covalent TCR-pMHC interactions can form through disulfide bonding between a cysteine residue at the apex of the TCR complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) and a cysteine within the presented peptide [32]. This covalent mechanism represents a fundamental shift in our understanding of antigen recognition, demonstrating that bond stability, rather than solely initial affinity, can dictate T cell signaling outcomes.

The implications of this discovery extend across adaptive immunity, particularly in thymic development where TCR signal strength directs lineage commitment. This covalent modality redirects T cell fate by inducing strong Zap70-dependent TCR signaling, triggering either thymocyte deletion or agonist selection in the thymic cortex [32] [33]. Understanding these interactions provides new insights into immune regulation and opens novel avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Mechanisms of Covalent TCR-pMHC Interactions

Structural Basis of Disulfide Bond Formation

Covalent TCR-pMHC interactions require specific structural configurations that allow disulfide bond formation:

- Strategic cysteine positioning: A free cysteine residue must be present at the apex of either the TCRα or TCRβ CDR3 loop, positioned to interact with a complementary cysteine in the peptide antigen [32]. This configuration occurs naturally in some TCRs and can be engineered into known TCR-pMHC combinations.

- Minimal structural rearrangement: Disulfide bond formation does not require significant structural rearrangement of either the TCR or the peptide, indicating that these interactions can occur within existing binding geometries [32] [33].

- Independence from initial affinity: Remarkably, these covalent bonds can form even when the initial noncovalent affinity of the TCR-pMHC interaction is low, suggesting a two-phase binding mechanism [32].

Table 1: Characteristics of Covalent vs. Noncovalent TCR-pMHC Interactions

| Characteristic | Noncovalent Interactions | Covalent Interactions |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Type | Hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, electrostatic | Disulfide bridge (Cysteine-Cysteine) |

| Interaction Lifetime | Typically short (seconds) | Exceptionally long (minutes to hours) |

| Dependence on Initial Affinity | Signaling correlates with affinity/dissociation rate | Effective even with low initial affinity |

| Impact on Antigen Specificity | High specificity | Reduced antigen specificity |

| T Cell Activation | Dependent on multiple rebinding events | Efficient with single binding events |

Biophysical and Signaling Consequences

The formation of a covalent TCR-pMHC complex has profound biophysical and signaling implications:

- Extended complex lifetime: The disulfide bond creates exceptionally long-lived TCR-pMHC complexes that resist mechanical disruption and prevent unbinding-rebinding cycles [32].

- Enhanced signal propagation: These stable complexes facilitate sustained recruitment and activation of ZAP-70 kinase, leading to potent downstream TCR signaling that exceeds thresholds required for specific T cell fate decisions [32].

- Altered force sensitivity: Unlike conventional TCR-pMHC bonds that can exhibit catch-bond behavior under force, covalent complexes are relatively force-insensitive, creating a stable signaling platform [32] [23].

- Broadened antigen recognition: By overcoming affinity limitations, covalent binding enables T cells to respond to pMHC ligands across a wide affinity spectrum, though at the cost of reduced antigen specificity [32].

Diagram 1: Covalent TCR-pMHC Signaling Pathway

Functional Consequences in T Cell Biology

Impact on Thymic Selection and T Cell Fate

Covalent TCR-pMHC interactions play a decisive role in thymic development, where signal strength determines T cell fate:

- Redirected thymocyte development: Engineered TCRs with cysteine residues at the CDR3α or CDR3β apex (6218αC and 6218βC) demonstrated dramatically altered development compared to their non-covalent counterpart (6218 TCR), skewing fate away from conventional CD8αβ+ T cell development [32].

- Induction of deletion and agonist selection: Cys-containing TCRs triggered strong TCR signaling that resulted in thymocyte deletion in the thymic cortex or promoted differentiation toward specialized lineages like CD8αα intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) [32].

- ZAP-70 dependence: The fate skewing induced by cysteine-containing CDR3 requires intact ZAP-70 signaling. In ZAP-70 deficient mice (Zap70mrd/mrt), thymocytes with cysteine-containing CDR3s that would normally be deleted undergo aberrant development into conventional T cells [32].

Table 2: T Cell Fate Outcomes Induced by Covalent TCR-pMHC Interactions

| T Cell Population | Effect of Covalent Interaction | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-selection Thymocytes | Induction of strong TCR signaling | Apoptotic deletion or agonist selection |

| CD8αβ+ Conventional T Cells | Reduced development | Depletion from peripheral repertoire |

| CD8αα Intestinal Intraepithelial Lymphocytes (IELs) | Enhanced development | Enrichment in intestinal epithelium |

| Regulatory T Cells (T-regs) | Potential for enhanced development | Possible application in autoimmunity |

Implications for Peripheral T Cell Responses

Beyond thymic development, covalent TCR-pMHC interactions influence peripheral T cell function:

- Enhanced antigen sensitivity: TCR-peptide disulfide bonds facilitate T cell activation by pMHC ligands with a wide spectrum of affinities, potentially lowering the threshold for activation [32] [33].

- Altered antigen specificity: While covalent binding increases sensitivity, it reduces the fine specificity of antigen recognition, potentially leading to cross-reactivity [32].

- Mechanical stability: The immunological synapse normally creates a biophysically stable environment with limited mechanical forces on TCR-pMHC bonds [23]. Covalent complexes provide inherent stability that may be particularly advantageous in specific microenvironments.

Methodological Approaches for Studying Covalent Interactions

Experimental Models and Reagents

The investigation of covalent TCR-pMHC interactions employs specialized experimental systems:

- TCR-retrogenic mouse models: Bone marrow from Rag1-/- or Tcra-/- mice is transduced with retroviruses encoding engineered TCRs (e.g., 6218, 6218αC, 6218βC) and transferred into irradiated recipients to study T cell development in vivo [32].

- Structural biology techniques: Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis reveals two-phase TCR-pMHC interaction kinetics with noncovalent and covalent components, while X-ray crystallography provides atomic-level structural details [32].

- Single-molecule force spectroscopy: Molecular force sensors (MFS) incorporating FRET pairs quantify TCR-imposed molecular forces within immunological synapses, though studies show CD4+ T cells exert surprisingly low forces [23].

Computational and Structural Prediction Advances

Computational methods are increasingly valuable for studying these interactions:

- AlphaFold-Multimer applications: Advanced structural modeling pipelines predict TCR-pMHC complex structures, though confidence scores may overestimate docking accuracy [10].

- Graph neural network enhancements: GNN-based solutions improve docking quality scoring and structural model selection, achieving a 25% increase in correlation with DockQ quality scores [10].

- NMR solution mapping: SMART A*02:01, a designed single-chain MHC-I protein with reduced molecular weight, enables solution NMR mapping of TCR docking orientations in physiologically relevant conditions [34].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Covalent Interaction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Covalent TCR-pMHC Interactions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered TCR-Retrogenic Mice | In vivo assessment of T cell development and fate decisions | Rag1-/- BM transduced with cysteine-modified TCRs (e.g., 6218αC, 6218βC) [32] |

| SMART MHC-I Proteins | Solution NMR mapping of TCR docking orientations | Single-chain design (e.g., SMART A*02:01) with reduced molecular weight [34] |

| Molecular Force Sensors (MFS) | Single-molecule quantification of TCR-imposed forces | FRET-based sensors on SLBs; measures 1-10 pN range [23] |

| AlphaFold-Multimer Pipeline | Computational prediction of TCR-pMHC complex structures | Includes MSA/template perturbation for model diversity [10] |

| Graph Neural Network Scorer | Improved quality assessment of predicted TCR-pMHC models | DockQ regression; 25% improvement in correlation [10] |