Decoding Thymic Involution: A Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Atlas of Aging Dynamics

This comprehensive review synthesizes recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) that are revolutionizing our understanding of thymus aging.

Decoding Thymic Involution: A Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Atlas of Aging Dynamics

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) that are revolutionizing our understanding of thymus aging. We explore the cellular and molecular drivers of age-related thymic involution, focusing on thymic epithelial cells (TECs), thymocyte development, and stromal remodeling. The article details methodological frameworks for scRNA-seq data integration, spatial transcriptomics, and computational analysis of aging thymus atlases. We highlight key biomarkers like IGFBP5 and transcription factors associated with thymic aging, validate findings across human and mouse models, and discuss implications for rejuvenation strategies and therapeutic interventions against age-related immune decline.

Cellular Landscape of Thymic Aging: Resolving Cell Type-Specific Trajectories

Thymic Epithelial Cell (TEC) Heterogeneity and Maturation Dynamics Across Lifespan

Thymic epithelial cells (TECs) constitute the essential stromal microenvironment of the thymus, directing T cell lineage commitment, selection, and tolerance induction. Recent advances in single-cell technologies have revealed unprecedented heterogeneity within the TEC compartment, transitioning from a traditional binary classification of cortical (cTEC) and medullary (mTEC) populations to a complex spectrum of subtypes with distinct functions, developmental origins, and spatial distributions [1] [2]. This cellular diversity is not static but undergoes profound reorganization across the lifespan, with significant implications for immune competence. The establishment of a comprehensive thymic aging single-cell RNA sequencing atlas has been instrumental in mapping these dynamics, revealing that aging disrupts thymic progenitor differentiation and impairs core immunological functions, leading to diminished T cell output and altered T cell receptor repertoire diversity [2]. This technical guide synthesizes current understanding of TEC heterogeneity and maturation dynamics, providing researchers with methodological frameworks and analytical tools to advance this rapidly evolving field.

Deciphering TEC Heterogeneity: From Embryonic Development to Aging

Comprehensive Classification of TEC Subtypes

The TEC compartment comprises multiple transcriptionally and functionally distinct subtypes that emerge during organogenesis and persist throughout life, though their relative frequencies shift dramatically with age.

Table 1: Major TEC Subtypes and Their Characteristic Markers

| TEC Subtype | Key Marker Genes | Primary Functions | Developmental Window |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perinatal cTEC | Syngr1, Gper1, CD83, CD40 [1] [2] | Efficient positive selection [1] | Predominant early postnatal, rare in adults [1] |

| Mature cTEC | Prss16, Cxcl12, Psmb11 [3] [2] | T cell lineage commitment, positive selection [4] | From 4 weeks of life onwards [1] |

| Intertypical TEC | Ccl21a, Krt5, Pdpn, Ly6a [1] [2] [5] | Progenitor potential, localized at CMJ [1] | All postnatal stages [2] |

| Aire+ mTEC | Aire, Cd52, Fezf2 [4] [2] | Promiscuous gene expression for negative selection [4] | Expand during first weeks of life [4] |

| Post-Aire mTEC | Krt80, Spink5 [2] | Terminal differentiation [4] | All postnatal stages [4] |

| Tuft-like mTEC | Avil, Trpm5, Dclk1 [2] [5] | Immune surveillance [2] | All postnatal stages |

| TECtuft | Avil, L1cam [6] | Specialized immune function | Identified in aged mice [6] |

| Age-associated TEC (aaTEC) | Partial EMT markers [6] | Non-functional, act as sink for regeneration signals | Emerges with age, expands after injury [6] |

Developmental Dynamics of TEC Subpopulations

TEC heterogeneity emerges during embryonic development and undergoes continuous remodeling throughout life. Single-cell transcriptomic analyses of mouse thymus spanning embryonic to adult stages have revealed intricate differentiation trajectories and temporal dynamics [5]. The earliest thymic epithelial progenitors (TEPCs) appear around embryonic day 10.5-12.5, with studies demonstrating that individual Epcam-positive precursor cells can generate both mTECs and cTECs, confirming their bipotent nature [5]. A critical transition occurs during the first weeks of postnatal life, characterized by a conspicuous inversion in the cTEC/mTEC ratio that correlates with intensifying thymopoiesis [4]. This period also sees the expansion and functional diversification of the medullary compartment, with increasing abundance of Aire+ and Fezf2+ mTECs essential for establishing central tolerance [4].

The perinatal to adult transition is marked by a dramatic shift in TEC subpopulation frequencies. Perinatal cTECs represent approximately 40% of all TECs in the first week after birth but rapidly decrease thereafter, being largely replaced by mature cTECs from 4 weeks of life onwards [1]. This shift has functional consequences, as perinatal cTECs demonstrate exceptional efficiency in positive selection compared to their mature counterparts [1]. Concurrently, intertypical TECs (Ccl21a+ Krt5+), which localize at the cortico-medullary junction and display progenitor characteristics, persist throughout postnatal development [1] [2].

Age-Associated Remodeling of TEC Compartments

Aging triggers profound structural and functional alterations in the TEC compartment. Single-cell RNA sequencing of nonhematopoietic stromal cells from young (2-month) and aged (18-month) mice reveals the emergence of two atypical thymic epithelial cell states—aaTEC1 and aaTEC2—that form high-density peri-medullary epithelial clusters devoid of thymocytes [6]. These age-associated TECs exhibit features of partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and are associated with downregulation of the critical thymic regulator FOXN1 [6].

The accumulation of aaTECs represents a key feature of thymic involution, drawing tonic signals away from functional TEC populations and acting as a sink for TEC growth factors such as FGF and BMP signaling [6]. This phenomenon is exacerbated by acute injury and correlates with defective repair mechanisms in the aged thymus. Beyond the emergence of novel cell states, aging disrupts the progenitor cell compartment, with an early-life cortical precursor population being virtually extinguished at puberty and a medullary precursor entering quiescence, thereby impairing maintenance of the medullary epithelium [2].

Table 2: Quantitative Changes in TEC Populations Across Lifespan in Mice

| Parameter | 1 Week | 4 Weeks | 16 Weeks | 18 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total TEC cellularity | High | Declines by ~50% [2] | ~50% of 1-week level [2] | Severely diminished [6] |

| Perinatal cTEC frequency | ~40% of all TEC [1] | Low | Very rare [1] | Not detected |

| mTEC:cTEC ratio | Lower | Increases [4] | Higher | Altered, with mTEC more severely depleted [6] |

| Aire+ mTEC | Emerging | Expanding [4] | Established | Diminished promiscuous gene expression [4] |

| TEC proliferative rate | High | Declining [4] | Low | Rare [4] |

Technical Frameworks for TEC Analysis

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Methodologies

Single-cell RNA sequencing has revolutionized the resolution of TEC heterogeneity. The following experimental workflow has been successfully applied to profile TEC populations across development and aging:

Cell Isolation and Preparation:

- Mechanical and enzymatic dissociation of thymic tissue using collagenase/dispase blends [3]

- EpCAM-based enrichment for TECs using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to overcome stromal cell rarity [6] [2]

- Viability preservation through ice-cold processing and viability dye staining

Single-Cell Library Preparation:

- Droplet-based scRNA-seq (10x Genomics) for high-throughput profiling [7] [3]

- SMART-Seq2 for full-length transcript coverage when analyzing index-sorted subpopulations [2]

- Cellular hashing with sample-specific barcodes for multiplexed analysis of multiple timepoints or conditions [7]

Multimodal Single-Cell Approaches:

- CITE-seq (Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing) for simultaneous measurement of surface protein and mRNA expression [1] [7]

- Single-cell ATAC-seq for chromatin accessibility profiling [8]

Spatial Mapping Techniques

Understanding TEC organization within intact thymic tissue requires spatial resolution, for which several advanced methodologies have been developed:

Spatial Transcriptomics:

- 10x Visium platform for genome-wide expression profiling within morphological context [7]

- Integration with H&E staining for correlative analysis of cellular organization and gene expression [7]

Multiplexed Protein Imaging:

- IBEX (Immunolabeling-based Epitope eXclusion) for high-resolution cyclic immunofluorescence imaging [7]

- 44-plex IBEX panels enabling simultaneous detection of multiple TEC markers and structural proteins [7]

- RareCyte protein imaging for validation studies [7]

Computational Framework for Spatial Data Integration:

- TissueTag computational framework for (semi)automatic tissue annotation and construction of a Common Coordinate Framework (CCF) [7]

- OrganAxis construction, specifically the Cortico-Medullary Axis (CMA) for the thymus, enabling quantitative comparison across samples and modalities [7]

- Pixel classification to distinguish cortex, medulla, and border regions [7]

Functional Validation Approaches

Lineage Tracing:

- Genetic fate mapping using Cre-lox systems under cell type-specific promoters (e.g., β5t-Cre for cTEC-lineage tracing) [5]

- Interspecific thymus transplantation assays to assess TEC progenitor potential [5]

Mass Cytometry and High-Dimensional Flow Cytometry:

- Infinity Flow computational pipeline for massively parallel flow cytometry analysis of 260+ cell surface markers [1]

- Machine learning algorithms to impute expression levels at single-cell resolution based on backbone markers [1]

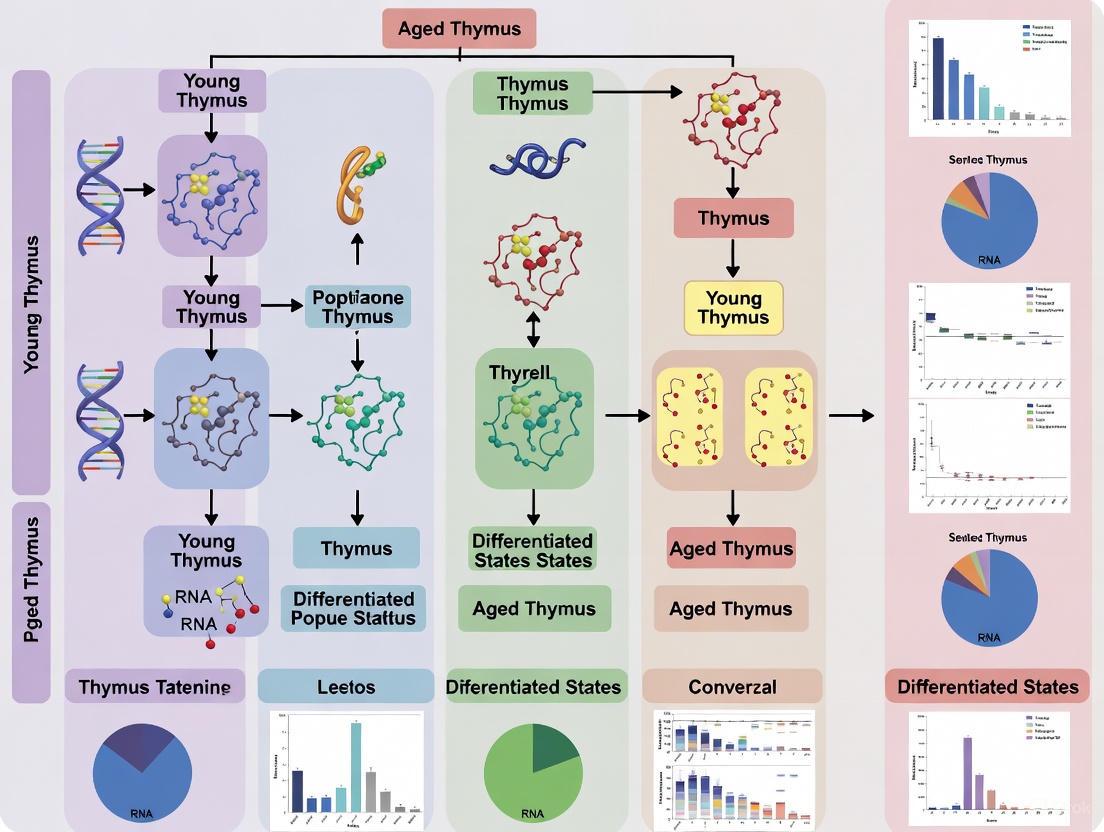

Diagram Title: Integrated Workflow for TEC Analysis

Signaling Pathways Regulating TEC Maturation and Maintenance

The development and maintenance of TEC populations are governed by intricate signaling networks that change across the lifespan. These pathways represent potential therapeutic targets for thymic regeneration and function preservation.

NF-κB Signaling Pathway:

- Essential for mTEC maturation and diversification through RANK, CD40, and LTβR receptors [4]

- Coordinates with lymphoepithelial crosstalk to drive Aire expression and promiscuous gene expression [4]

- Age-related decline contributes to diminished medullary function [2]

FOXN1 Regulatory Network:

- Master regulator of TEC differentiation maintained throughout TEC development [4] [5]

- Downregulated in age-associated TECs, contributing to functional decline [6]

- Transgenic expression shown to expand TEC compartment and enhance thymopoiesis [4]

FGF and BMP Signaling:

- Trophic factors for TEC maintenance and regeneration [6]

- Hijacked by age-associated TECs that act as signaling sinks, diverting resources from functional TECs [6]

- Bmp4 expressed by venous endothelial cells supports thymic regeneration after acute insult [6]

Wnt Signaling:

- Maintains progenitor cell populations in postnatal thymus [5]

- Expression of Wnt4 identified in label-retaining cTECs with progenitor properties [5]

Diagram Title: Signaling Networks in TEC Biology

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for TEC Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse Models | Foxn1-EGFP knockin [5], β5t-Cre [5], hK14: Cre-ERT2 [5] | Lineage tracing, isolation of specific TEC subsets |

| Cell Surface Markers | CD83, CD40, HVEM (CD270), Ly51, UEA1, EpCAM, MHCII, CD80 [1] | Identification of novel TEC subpopulations by flow cytometry |

| Computational Tools | ThymoSight (www.thymosight.org) [6], TissueTag [7], Infinity Flow [1], SingleR [1] | Analysis of scRNA-seq data, cell type annotation, spatial data integration |

| Antibody Panels | 260+ exploratory surface markers [1], 44-plex IBEX panel [7] | High-dimensional phenotyping, multiplexed spatial imaging |

| Spatial Framework | Cortico-Medullary Axis (CMA) [7] | Quantitative spatial analysis across samples and modalities |

| Glycoproteomic Tools | StrucGP [9], Glyco-Decipher [9] | Analysis of site-specific N-glycosylation in aging thymus |

Concluding Perspectives and Future Directions

The resolution of TEC heterogeneity and maturation dynamics across the lifespan has accelerated dramatically with the advent of single-cell and spatial technologies. The emergence of comprehensive thymic aging atlases has identified novel cellular states, including age-associated TECs that actively contribute to functional decline by sequestering regenerative signals [6]. These findings provide a molecular framework for understanding why thymic regenerative capacity diminishes with age and following injury.

Future research directions should focus on leveraging these insights for therapeutic development. Potential strategies include targeting aaTECs to redirect trophic signals to functional TEC populations, manipulating progenitor cell quiescence to enhance thymic maintenance, and developing approaches to preserve thymic function during cancer therapies and transplantation. The integration of multi-omic datasets—including recent glycoproteomic findings that reveal marked decline in oligo-mannose glycans and increased bisecting GlcNAc modifications in the aged thymus [9]—will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving thymic involution.

As these technologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly reveal additional layers of complexity in TEC biology and identify new targets for therapeutic intervention in age-related immune decline and regenerative medicine.

Age-Related Shifts in Thymocyte Development and T-lineage Commitment

The thymus, the primary organ responsible for the generation and selection of T cells, undergoes a profound and progressive functional decline with age, a process known as thymic involution [10] [11]. This process is one of the most universally recognized alterations of the aging immune system and is characterized by a reduction in tissue mass, loss of normal tissue architecture, a dramatic decline in thymocyte numbers, and consequently, a reduced output of naïve T cells [10] [11]. While this decline was historically viewed as a simple quantitative reduction in output, recent advances, particularly those leveraging single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics, have revealed that aging is accompanied by complex qualitative changes in both the developing thymocytes and the specialized thymic microenvironment that supports them [12] [6] [13]. These changes are not merely a passive withering but an active remodeling that alters the fundamental processes of T-lineage commitment and thymic selection. This in-depth technical guide synthesizes findings from recent single-cell atlas research to elucidate the cellular and molecular mechanisms underpinning age-related shifts in thymocyte development, providing a framework for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to interrogate or therapeutically modulate this critical immunological process.

Age-Associated Remodeling of the Thymic Microenvironment

The stromal microenvironment of the thymus, particularly thymic epithelial cells (TECs), provides essential signals for thymocyte survival, proliferation, lineage commitment, and selection. Age-related changes in this niche are a primary driver of dysfunctional thymopoiesis.

Emergence of Dysfunctional Thymic Epithelial Cell States

Single-cell transcriptomic analyses of the non-hematopoietic stromal compartment from young (2-month-old) and aged (18-month-old) mice have identified the emergence of two distinct age-associated TEC (aaTEC) states (aaTEC1 and aaTEC2) that are virtually absent in young thymi [6]. These aaTECs form high-density peri-medullary epithelial clusters that are notably devoid of thymocytes, representing an accretion of non-productive tissue [6]. Transcriptomically, these cells exhibit features of a partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and a downregulation of FOXN1, a master transcription factor essential for TEC differentiation and function [6]. Functionally, aaTECs are not merely passive bystanders; interaction analyses suggest they act as a "sink" for tonic signals and key TEC growth factors (such as FGF and BMP pathways), thereby diverting critical support away from functional cTEC and mTEC populations. Following acute injury, this population expands substantially, further perturbing trophic regeneration pathways and correlating with defective repair of the involuted thymus [6].

Progenitor Exhaustion and Altered Cellular Composition

Beyond the appearance of novel states, aging disrupts the progenitor compartments that maintain the thymic epithelium. A precursor cell population retained in the mouse cortex postnatally is virtually extinguished around puberty [13]. Concurrently, a medullary precursor population enters a state of quiescence, impairing the maintenance of the medullary epithelium [13]. This erosion of progenitor potential is a fundamental mechanism underpinning the failure of TEC regeneration in aged individuals. Flow cytometric and scRNA-seq data confirm a significant decline in total TEC cellularity with age, with a more severe loss observed in medullary TECs (mTECs) compared to cortical TECs (cTECs) [6] [13].

Table 1: Age-Related Changes in Key Thymic Stromal Populations

| Cell Population | Change with Age | Functional Consequence | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical TEC (cTEC) | Moderate decrease in cellularity | Compromised positive selection of thymocytes | [6] [13] |

| Medullary TEC (mTEC) | Severe decrease in cellularity; emergence of aaTEC clusters | Impaired negative selection and Treg generation; disrupted medullary organization | [6] [13] |

| Early Cortical Progenitor | Virtual extinction by puberty | Loss of regenerative capacity for cortical epithelium | [13] |

| Medullary Progenitor | Entry into quiescence | Failure to maintain medullary epithelium long-term | [13] |

| Thymic Fibroblasts | Transcriptional shift towards "inflammaging" | Altered cytokine signaling, contributing to stromal dysfunction | [6] |

Functional Consequences for Thymocyte Development and Selection

The aged thymic microenvironment creates a compromised developmental landscape, leading to defects in the thymocytes themselves and the core immunological function of the organ.

Intrinsic Defects in Developing Thymocytes

Thymocytes from aged mice exhibit several cell-intrinsic functional deficiencies. They show a reduced proliferative capacity in response to TCR stimulation, with an apparent inability to progress from the S phase to the G2/M phase of the cell cycle [10]. Furthermore, aged thymocytes display increased resistance to spontaneous and dexamethasone-induced apoptosis [10]. This aberrant survival may foreshadow the increased resistance to apoptosis observed in peripheral T cells from aged individuals. Phenotypically, alterations include a declining trend in the percentage of CD3+ thymocytes and a significant decrease in CD3 median fluorescence intensity, suggesting a lower number of TCR complexes per cell, which could impair TCR signaling strength during selection [10].

Compromised Central Tolerance and Altered TCR Repertoire

The medulla's role in enforcing central tolerance is notably compromised with age. Flow cytometric profiling of thymocytes undergoing negative selection reveals that the proportion of semi-mature CD4+ and CD8+ single-positive thymocytes being negatively selected in the medulla diminishes with age [13]. This functional deficit is linked to age-associated changes in the mTEC compartment, which is critical for presenting self-antigens. Bulk TCR sequencing of the most mature CD4+ SP thymocytes shows that the diversity of the TCR repertoire increases significantly with age, and the sequences incorporate more non-templated nucleotides [13]. While the repertoire remains robust in terms of V(D)J segment usage, the impairment in negative selection likely allows a greater number of self-reactive clones to escape into the periphery, potentially contributing to the age-associated rise in autoimmunity.

Table 2: Functional Defects in Thymocytes and Tolerance Mechanisms with Aging

| Process | Observation in Aged Thymus | Technical Assay for Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Proliferation | Reduced proliferative response to ConA/IL-2; cell cycle block | In vitro stimulation with tritiated thymidine incorporation or propidium iodide cell cycle analysis [10] |

| Apoptosis | Increased resistance to spontaneous and dexamethasone-induced apoptosis | In vitro culture with/without dexamethasone and analysis by Annexin V/PI staining [10] |

| TCR Signaling | Decreased surface CD3 expression (MFI) | High-resolution flow cytometry for CD3 median fluorescence intensity [10] |

| Negative Selection | Reduced proportion of semi-mature SP thymocytes undergoing negative selection | Flow cytometry for Helios+ PD-1+ populations in specific thymocyte subsets [13] |

| TCR Repertoire | Increased diversity and longer CDR3 lengths | Bulk TCR sequencing (e.g., ImmunoSEQ) of sorted mature SP thymocytes [13] |

Molecular Drivers: Insights from Single-Cell and Spatial Atlas Studies

Cut-edge spatial and single-cell genomic technologies are defining the precise gene-regulatory programs that dictate age-related thymic involution.

Divergent Gene-Regulatory Programs

A transcriptional and chromatin accessibility atlas of T cell development in neonatal and adult mice revealed that poised gene expression programs vary with age from the earliest stages of thymocyte genesis [12]. Neonates possess more accessible chromatin during early thymocyte development, which is thought to establish poised programs that manifest later in development [12]. A specific gene module was found to diverge with age, including programs governing effector response and the cell cycle. Through a CRISPR-based perturbation approach coupled with scRNA-seq, the conserved transcriptional regulator Zbtb20 was identified as a contributor to these age-dependent differences in T cell development [12].

Spatial Reorganization and Signaling Gradients

The establishment of a Common Coordinate Framework (CCF) for the human thymus, termed the Cortico-Medullary Axis (CMA), has enabled a spatially resolved analysis of thymic organization across pre- and early postnatal stages [7]. This approach demonstrates that the establishment of the lobular cytokine network and canonical thymocyte trajectories occurs by the beginning of the second trimester. Furthermore, it has pinpointed divergence in the timing of medullary entry between CD4 and CD8 T cell lineages [7]. In aging, the breakdown of this precise spatial coordination, exemplified by the formation of aaTEC clusters devoid of thymocytes, disrupts the local signaling gradients essential for proper thymocyte migration and selection.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Age-Related Thymic Changes

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Thymic Stroma

Objective: To comprehensively characterize the transcriptional states of all stromal cells (TECs, endothelial cells, fibroblasts) and identify novel, age-specific populations.

Detailed Workflow:

- Tissue Processing: Thymi from mice of defined age groups (e.g., 2-month vs. 18-month) are harvested and mechanically dissociated. For TEC-focused studies, thymic lobes are finely minced and digested enzymatically (e.g., with collagenase/dispase) to create a single-cell suspension [6] [13].

- Stromal Cell Enrichment: Hematopoietic cells (CD45+) and endothelial cells (CD31+) are depleted using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) or flow cytometry to enrich for the stromal compartment, particularly TECs (EpCAM+ CD45-) [6].

- Single-Cell Partitioning and Library Prep: The enriched cell suspension is loaded onto a microfluidic platform (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium). Cells are partitioned into gel bead-in-emulsions (GEMs) where cell lysis, barcoding, and reverse transcription occur to generate barcoded cDNA.

- Sequencing and Data Processing: Libraries are sequenced on an Illumina platform. The raw data is processed using cellranger or a similar pipeline to generate a gene-cell count matrix.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Downstream analysis is performed in R or Python using Seurat or Scanpy. Steps include quality control, normalization, integration of samples from different ages, dimensionality reduction (PCA, UMAP), graph-based clustering, and differential gene expression analysis to define clusters and identify age-dependent changes [6] [13] [14].

Spatial Transcriptomics and Construction of a Common Coordinate Framework

Objective: To map transcriptional data within the morphological context of the thymus and analyze gene expression gradients across anatomical regions.

Detailed Workflow:

- Tissue Preparation: Fresh-frozen or FFPE thymus tissue sections (e.g., 10 µm thickness) are mounted on Spatial Transcriptomics slides (e.g., 10x Visium) [7].

- Staining and Imaging: Sections are stained with H&E and imaged to capture histology. The tissue is then permeabilized to release mRNA, which binds to spatially barcoded oligos on the slide surface.

- Library Construction and Sequencing: The barcoded cDNA is synthesized, amplified, and sequenced.

- Data Integration and CCF Construction:

- Tissue Annotation: H&E images are (semi-)automatically annotated using a computational framework like TissueTag to define key histological regions (cortex, medulla, capsule, vessels) [7].

- OrganAxis Calculation: A Common Coordinate Framework (CCF), such as the Cortico-Medullary Axis (CMA), is constructed based on distance measurements from these histological landmarks. This assigns a continuous positional value to each Visium spot, enabling integration of data from different samples and modalities [7].

- Analysis: Gene expression can be mapped and visualized along the CMA, revealing spatial gradients and region-specific changes with age.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Thymus Aging Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CD45- EpCAM+ Sort Protocol | Isolation of pure thymic epithelial cells (TECs) for scRNA-seq or functional assays. | Flow cytometric sorting to separate cTEC (Ly51+ UEAI-) and mTEC (Ly51- UEAI+) subsets from aged mice [6] [13]. |

| ThymoSight (www.thymosight.org) | Integrated web tool for interrogating published and user-uploaded thymic scRNA-seq datasets. | Mapping novel TEC clusters from an aged mouse dataset against publicly available young-stroma signatures to identify conserved and novel populations [6]. |

| TissueTag Python Package | Computational framework for cross-platform imaging data analysis and OrganAxis construction. | Building a Cortico-Medullary Axis (CMA) from H&E-stained human fetal and pediatric thymus sections to integrate spatial transcriptomics data [7]. |

| FOXN1 Reporter Mice | Genetic tools to trace and quantify TEC function and differentiation status in vivo. | Lineage-tracing experiments to determine the contribution of FOXN1+ progenitor cells to the TEC pool in aged versus young mice [6]. |

| CRISPR Perturbation + scRNA-seq | Functional screening of candidate genes in a pooled format with single-cell readout. | Identifying transcriptional regulators like Zbtb20 that contribute to age-dependent gene expression programs in developing thymocytes [12]. |

Transcriptional Profiling of Cortical and Medullary TEC Subpopulations

The thymus is a primary lymphoid organ essential for the development of a diverse and self-tolerant T cell repertoire. This function is critically dependent on the stromal microenvironment, with thymic epithelial cells (TECs) playing a paramount role [15] [16]. TECs are broadly categorized into cortical (cTECs) and medullary (mTECs) subpopulations, each responsible for distinct stages of T cell development and selection [15]. cTECs mediate T lineage commitment and positive selection of thymocytes, while mTECs are crucial for the deletion of autoreactive T cells and the establishment of central immune tolerance [15] [6]. A defining feature of mTECs is their expression of a vast repertoire of tissue-restricted antigens (TRAs), a process regulated in part by the transcriptional regulator AIRE [15] [6].

The thymus undergoes a process of age-related involution, characterized by a progressive reduction in tissue mass and cellularity, leading to diminished output of naïve T cells [17] [18] [6]. This decline in function is a major contributor to impaired immune responsiveness in the elderly. Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) have revealed that the thymic stroma is composed of remarkably heterogeneous cell populations, and that this complexity is profoundly altered during aging [15] [6] [7]. This technical guide synthesizes current knowledge on the transcriptional profiling of cTEC and mTEC subpopulations, framing these findings within the context of thymic aging and providing a resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Cellular Heterogeneity of the Thymic Stroma

Single-cell transcriptional profiling has fundamentally expanded the understanding of thymic stromal heterogeneity beyond the traditional cTEC/mTEC dichotomy. The stromal compartment is a complex ecosystem comprising epithelial, mesenchymal, endothelial, and other non-hematopoietic cells, all of which contribute to the thymic microenvironment [15] [7].

A Catalog of Thymic Stromal Cells

Unbiased clustering of scRNA-seq data from human thymi across fetal, postnatal, and adult stages identifies numerous stromal populations [15] [7]. The epithelial compartment itself can be divided into multiple distinct sub-clusters, while the non-epithelial stroma includes several critical supportive populations.

Table 1: Major Non-Epithelial Stromal Populations in the Human Thymus

| Cell Type | Key Marker Genes | Proposed Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Cells | PDGFRA, LUM, LAMA2 |

Structural support, expression of WNT, BMP, IGF, and FGF pathway ligands to regulate TEC development [15]. |

| Pericytes | PDGFRB, MCAM, CSPG4 |

Vascular support, expression of INHBA (Activin A) and FRZB to modulate TEC differentiation [15]. |

| Vascular Arterial Endothelial Cells | PECAM1, VEGFC, GJA4 |

Formation of blood vessels, expression of homing chemokines [15]. |

| Vascular Venous Endothelial Cells | PECAM1, ACKR1, SELE, APLNR |

Include thymic portal endothelial cells (TPECs) for progenitor homing; high expression of BMP4 and TGFB1 [15] [6]. |

| Lymphatic Endothelial Cells | LYVE1, PROX1, CCL21 |

Formation of lymphatic vessels [15]. |

| Mesothelial Cells | MSLN, UPK3B, PRG4 |

Expression of WNT ligands and modulators (RSPO1, RSPO3) and BMP4 [15]. |

Deep Profiling of the TEC Compartment

Re-clustering of the epithelial superclusters reveals extensive diversity, identifying nine distinct TEC subpopulations in the human thymus [15]. These subpopulations represent states of differentiation, lineage commitment, and functional specialization.

Table 2: Transcriptomically Defined TEC Subpopulations in Human Thymus

| TEC Subpopulation | Key Marker Genes | Functional Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Immature TEC | FOXN1, PAX9, SIX1 |

Express TEC identity genes but lack functional cTEC/mTEC markers; putative progenitor population [15]. |

| cTEClo | PSMB11, PRSS16, CCL25 (low) |

Cortical TECs with lower expression of functional genes; contains proliferating (KI67+) cells [15]. |

| cTEChi | PSMB11, PRSS16, CCL25 (high) |

Mature cTECs with high expression of genes involved in positive selection [15]. |

| mTEClo | CLDN4, CCL21, HLA class II (low) |

Immature mTECs, include CCL21-expressing cells involved in thymocyte recruitment [15]. |

| mTEChi | SPIB, AIRE, FEZF2, HLA class II (high) |

Mature mTECs expressing AIRE and high levels of tissue-restricted antigens for negative selection [15]. |

| Corneocyte-like mTEC | KRT1, IVL |

Post-AIRE mTECs representing a terminal differentiation state [15] [6]. |

| Thymic Tuft Cells | AVIL, L1CAM, POU2F3 |

A thymic mimetic cell; can shape thymocyte development by promoting an IL-4-enriched environment [15] [6]. |

| Thymic Ionocytes | CFTR |

A newly identified medullary population; function not fully elucidated [15]. |

| Thymic Ciliated Cells | FOXJ1 |

Rare population; function in the thymus remains unclear [15]. |

Age-Associated Alterations in the TEC Compartment

Thymic involution is associated with profound quantitative and qualitative changes in TECs. Single-cell transcriptomics has been instrumental in identifying these alterations, which include shifts in population ratios and the emergence of novel, dysfunctional cellular states.

Quantitative and Phenotypic Shifts

With age, the thymus exhibits a relative decrease in the cortical-to-medullary ratio and an overall diminished TEC compartment, with medullary TECs (mTECs) being more severely affected than cortical TECs (cTECs) [6]. The expression of critical factors for TEC maintenance, such as FOXN1, declines [6]. Furthermore, there is a reduction in the expression of tissue-specific antigens (TSAs) within the mTEC compartment, which can potentially compromise the establishment of central tolerance in aged individuals [17].

Emergence of Age-Associated TECs (aaTECs)

A landmark discovery from recent scRNA-seq studies is the identification of age-associated TECs (aaTECs) in mice [6]. These cells are not found in young thymi but appear and accumulate with age, forming high-density peri-medullary clusters that are devoid of thymocytes. Two distinct states have been described:

- aaTEC1 and aaTEC2 exhibit features of a partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process associated with tissue fibrosis and dysfunction [6].

- Functionally, aaTECs act as a cellular "sink," drawing tonic signals (such as FGF and BMP) away from other functional TEC populations. This competition for trophic factors perturbs the stromal microenvironment and is associated with a defective regenerative response following acute injury in aged animals [6].

Experimental Methodologies for TEC Profiling

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Workflow

A standard workflow for profiling human thymic stroma involves the following key steps [15] [7]:

- Tissue Processing: Enzymatic digestion of fresh thymic tissue from donors of different ages (e.g., fetal, postnatal, adult) to create a single-cell suspension.

- Stromal Cell Enrichment: Depletion of CD45-positive immune cells using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). This enriches for both EpCAM+ CD45− epithelial cells and EpCAM− CD45− non-epithelial stromal cells.

- Single-Cell Library Preparation and Sequencing: Processing of enriched cells using platforms like the 10x Genomics Chromium system for droplet-based scRNA-seq. Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by sequencing (CITE-seq) can be simultaneously performed to integrate surface protein expression data [7].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Data Preprocessing: Quality control, filtering, and normalization using tools like CellRanger and Seurat.

- Batch Correction: Integration of datasets from multiple samples or ages using algorithms like BBKNN [15].

- Clustering and Annotation: Unsupervised graph-based clustering (e.g., Louvain algorithm) and annotation of cell types based on known marker genes.

- Spatial Mapping: Deconvolution of spatial transcriptomics data (e.g., 10x Visium) or integration with multiplexed protein imaging (e.g., IBEX) using a reference scRNA-seq atlas to infer spatial localization [7].

Diagram 1: scRNA-seq Workflow for TEC Profiling.

Spatial Mapping and the Common Coordinate Framework

A significant innovation in thymus research is the development of a Common Coordinate Framework (CCF), termed the Cortico-Medullary Axis (CMA), which enables quantitative integration of data across samples and technologies [7]. The TissueTag computational framework constructs this axis by using histology images to define key landmarks (capsule, cortex, medulla). The position of any cell or sequencing spot is then calculated based on its normalized distance to these landmarks, creating a continuous, quantitative axis from the subcapsular cortex to the inner medulla [7]. This allows for precise analysis of gene expression gradients and cell localization independent of discrete compartment annotations.

Diagram 2: Spatial Mapping via Cortico-Medullary Axis (CMA).

Key Signaling Pathways in TEC Biology

Stromal cells provide a network of soluble factors and cell-cell interactions that are critical for TEC development, maintenance, and function. Ligand-receptor interaction analysis from scRNA-seq data has highlighted several key pathways [15] [6].

Critical Pathways for TEC Development and Maintenance

- WNT Signaling: Mesenchymal cells express ligands like

WNT5Aand the modulatorRSPO3, while epithelial cells express corresponding receptors (ROR1,ROR2,RYK). The WNT inhibitorFRZBis expressed in pericytes and postnatal mesenchyme, suggesting dynamic regulation of this pathway during aging [15]. - BMP and FGF Signaling: Mesenchymal cells produce

BMP4,FGF7, andFGF10. Epithelial cells express receptors for these factors, which are crucial for TEC differentiation and proliferation [15]. - Activin-Follistatin Axis: The Activin A subunit (

INHBA) is expressed almost exclusively by pericytes, promoting TEC differentiation. Its antagonist, Follistatin (FST), is found in adult mesenchymal cells and promotes progenitor maintenance. The balance between these signals is disrupted in aging [15] [6]. - TGF-β Signaling: Most endothelial cells express

TGFB1and its receptorTGFBR2, implicating this pathway in vascular-stromal crosstalk [15].

Diagram 3: Key Signaling Pathways in TEC Biology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key reagents, markers, and tools essential for researching TEC subpopulations, as identified in the cited studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TEC Profiling

| Reagent / Resource | Function/Application | Example Targets / Models |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Markers for FACS | Isolation of live stromal cells and TEC subsets. | CD45 (immune cell depletion), EpCAM (pan-TEC), Ly51 (mouse cTEC), UEA-1 lectin (mouse mTEC), MHC-II, CD80 (mTEChi) [15] [18]. |

| Key Transcriptional Markers | Identification of TEC subsets via scRNA-seq or immunofluorescence. | cTECs: FOXN1, PSMB11 (β5t), PRSS16, CCL25 [15] [18]. mTECs: AIRE, CLDN4, SPIB, CCL21, KRT1 (corneocyte-like), POU2F3 (tuft) [15] [6]. |

| Genetic Mouse Models | Fate mapping and functional studies in vivo. | Foxn1Cre, β5t-Cre (TEC-specific), Rosa26:Myc (for TEC expansion), RANK-deficient mice (impaired mTEC development) [18] [16]. |

| Spatial Profiling Technologies | Mapping transcriptional and protein expression in tissue context. | 10x Visium (spatial transcriptomics), IBEX / RareCyte (highly multiplexed cyclic immunofluorescence) [7]. |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Data integration, clustering, and spatial analysis. | Seurat, Scanpy, BBKNN (batch correction), TissueTag (CMA construction) [15] [7]. |

Transcriptional profiling at single-cell resolution has unveiled an unexpected level of cellular diversity within the thymic stroma and provided a granular view of the molecular changes underlying thymic aging. The discovery of age-associated TECs (aaTECs) and their role as a sink for regenerative signals offers a novel mechanistic explanation for the failure of thymic regeneration in the elderly [6]. Furthermore, the establishment of a Cortico-Medullary Axis (CMA) provides a powerful quantitative framework for future studies to map cellular interactions and molecular gradients with high spatial precision [7].

These findings have significant implications for therapeutic strategies aimed at rejuvenating thymic function in the aging population or in patients recovering from cytoreductive therapies. Targeting the pathways that maintain functional TECs (e.g., FOXN1, Myc) or disrupting the formation of dysfunctional aaTECs could potentially reverse aspects of thymic involution [18] [6]. As these atlas-level datasets continue to grow, they will serve as an invaluable foundation for understanding immune aging and developing targeted interventions to restore compromised T cell immunity.

Progenitor Cell Depletion as a Driver of Thymic Involution

Thymic involution, the age-related functional decline and structural atrophy of the thymus, represents a cornerstone of immunosenescence. While stromal alterations contribute to this process, a growing body of evidence from single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) atlas research demonstrates that the depletion and functional impairment of progenitor cells are fundamental drivers of involution. This whitepaper synthesizes recent high-resolution molecular data to elucidate the mechanisms by which hematopoietic, thymic epithelial, and thymus-seeding progenitor populations are compromised with age. We detail the quantitative decline in these populations, the degradation of their supportive niches, and the resultant failure of thymic regenerative capacity. The insights herein provide a framework for therapeutic strategies aimed at rejuvenating thymic function by targeting progenitor cell biology.

The thymus is the primary organ responsible for the generation of a diverse and self-tolerant T-cell repertoire. Its functional output is critically dependent on a continuous supply of progenitor cells, including bone marrow-derived thymus-seeding progenitors (TSPs) and intrathymic stromal progenitors that maintain the epithelial microenvironment [19]. Age-related thymic involution has long been attributed to stromal degeneration and adipogenesis. However, advanced single-cell transcriptomic atlases now reveal that the depletion and functional quiescence of progenitor populations are initiating and sustaining factors in this process [20] [2]. This whitepaper reframes thymic involution through the lens of progenitor cell biology, leveraging scRNA-seq data to dissect the dynamics of progenitor depletion and its systemic consequences on immune competence.

Quantitative Profiling of Progenitor Depletion During Aging

Single-cell technologies have enabled the precise quantification of progenitor populations across the lifespan, revealing that their decline is an early and pervasive event in thymic involution.

Hematopoietic and Early Thymic Progenitors

The earliest signs of involution manifest in the bone marrow and the initial stages of intrathymic T-cell development. Quantitative studies show a significant reduction in lymphoid-primed progenitors, which directly impacts the thymic pipeline.

Table 1: Age-Associated Decline in Early T-Cell Progenitors and Their Precursors

| Progenitor Population | Tissue Location | Key Markers | Quantitative Change with Age | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early T-cell Progenitors (ETPs) | Thymus | CD44⁺ c-Kit⁺ CD25⁻ | ↓ Significant decline by 3 months in mice [20] | Reduced feedstock for all downstream T-cell subsets |

| Thymus-Seeding Progenitors (TSPs) | Blood / Bone Marrow | Lin⁻ Flk2⁺ CD27⁺ | ↓ Sharp drop in circulating numbers by 3 months [20] | Diminished influx of progenitors into the thymus |

| Bone Marrow Lymphoid Progenitors | Bone Marrow | Lin⁻ Sca-1⁺ c-Kit⁺ (LSK) | ↓ Substantially reduced by 3 months [20] | Limited generation of T-lineage-committed cells |

The data in Table 1 demonstrate that the initial reduction in intrathymic ETPs is not primarily due to a lack of space but rather a lack of settlers. The number of functional TSP/ETP niches remains stable into middle age (12 months in mice), yet the thymus is not seeded effectively because the pool of circulating and bone marrow-resident progenitors is depleted [20]. This creates a pre-thymic bottleneck that severely restricts T-cell production.

Thymic Epithelial Cell (TEC) Progenitors

The stromal scaffold of the thymus, essential for T-cell development and selection, is also maintained by progenitor cells. scRNA-seq analyses have uncovered that aging disrupts the differentiation and maintenance of these stromal progenitors.

Table 2: Alterations in Thymic Stromal Progenitor Populations with Aging

| Progenitor Population | Thymic Region | Key Markers / Features | Change with Age | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Precursor Population | Cortex | Identified via lineage-tracing [2] | ↓ Virtually extinguished at puberty [2] | Failure to maintain cortical TEC (cTEC) compartment |

| Medullary Precursor Cell | Medulla | Identified via lineage-tracing [2] | → Enters a quiescent state [2] | Impaired maintenance of medullary TEC (mTEC) compartment |

| Age-associated TECs (aaTECs) | Peri-medullary | Features of EMT, low FOXN1 [6] | ↑ Forms non-functional clusters, acts as a "sink" for growth factors [6] | Perturbs trophic regeneration pathways and limits repair |

A key discovery is the emergence of age-associated TECs (aaTECs), which are atypical epithelial cell states that form dense, thymocyte-devoid clusters [6]. These aaTECs exhibit features of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and act as a signaling "sink," sequestering growth factors like FGF and BMP away from functional progenitor niches, thereby further crippling regenerative responses after injury [6].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

This section outlines the core methodologies used to generate the critical findings discussed herein, providing a template for replication and further investigation.

Multicongenic Transfer for Quantifying Functional TSP Niches

This protocol is designed to quantify the number of available and functional progenitor niches in the thymus, independent of progenitor supply [20].

- Step 1: Progenitor Isolation. Lin⁻Flk2⁺CD27⁺ bone marrow progenitors, which encompass all thymus-seeding activity, are isolated via Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) from eight distinct congenic mouse strains.

- Step 2: Progenitor Pooling. Progenitors from all eight strains are mixed at precisely equal ratios to create a competitive reconstitution mixture.

- Step 3: Non-Irradiated Transfer. The pooled progenitor mix is transplanted into non-irradiated, non-ablated recipient mice of varying ages (e.g., 1 to 12 months). The use of non-irradiated hosts allows for the assessment of niche availability without creating artificial space.

- Step 4: Analysis and Modeling. After 21 days (allowing one complete wave of T-cell differentiation), donor chimerism in the recipient thymi is analyzed by flow cytometry. The number of distinct donor strains present is quantified. Mathematical modeling is applied to this data to estimate the absolute number of available TSP niches.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing and Lineage-Tracing of TEC Progenitors

This integrated protocol defines stromal progenitor heterogeneity and tracks their fate over time [6] [2].

- Step 1: Stromal Cell Enrichment. Thymic tissue is digested enzymatically, and non-hematopoietic stromal cells (CD45⁻) are enriched using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) or FACS.

- Step 2: High-Throughput scRNA-seq. Single-cell suspensions are loaded onto a platform (e.g., 10x Genomics) for droplet-based scRNA-seq library preparation and sequencing.

- Step 3: Lineage-Tracing Model. To complement snRNA-seq, a genetic lineage-tracing mouse model (e.g., employing a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase under a progenitor-specific promoter) is used. Following induction at a specific age (e.g., 4 weeks), the fate of labeled progenitor cells and their descendants is tracked over months through flow cytometry and histology.

- Step 4: Computational Integration. scRNA-seq data is analyzed using Seurat or Scanpy pipelines for clustering, differential expression, and trajectory inference (e.g., Monocle, PAGA). The transcriptional clusters are directly integrated with the lineage-tracing data to define progenitor identities and their differentiation dynamics across the lifespan.

Signaling Pathways in Progenitor Maintenance and Decline

The depletion of progenitors is orchestrated by the dysregulation of key conserved signaling pathways. The diagram below synthesizes findings from multiple studies to illustrate the core signaling network that fails during aging.

Diagram 1: Dysregulated Signaling Network in the Aged Thymic Niche. This diagram illustrates how key supportive signals for progenitors are disrupted with age. Critically, Notch signaling is diminished in both the bone marrow and thymic microenvironments by 3 months of age, compromising T-lineage commitment [20]. Concurrently, the emergence of age-associated TECs (aaTECs) creates a signaling "sink" that sequesters essential trophic factors like FGF and BMP, starving functional TEC progenitors and promoting a non-functional, EMT-like state [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table compiles key reagents and tools, as identified in the cited research, that are essential for investigating progenitor dynamics in thymic involution.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Thymic Progenitor Depletion

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Specific Example / Marker | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multicongenic Mouse Strains | Animal Model | CD45.1, CD45.2, Thy1.1 variants [20] | Enables quantitative niche analysis and competitive reconstitution assays. |

| Lineage-Tracing Model | Genetic Model | Inducible Cre under Foxn1 or other progenitor-specific promoters [2] | Tracks fate of specific TEC progenitor populations over time in vivo. |

| Cell Surface Markers (Flow Cytometry) | Reagent Panel | For ETPs: CD44⁺ c-Kit⁺ CD25⁻ CD4⁻ CD8⁻ [20] | Isolation and quantification of specific progenitor populations by FACS. |

| scRNA-seq Reference Atlas | Data Resource | Integrated atlas (e.g., ThymoSight [6]) | Benchmark for identifying novel cell states (e.g., aaTECs) and transcriptional changes. |

| Antibody for IGFBP5 | Detection Reagent | Validated anti-IGFBP5 antibody [21] | Detects a protein marker upregulated in aging TECs, associated with EMT and involution. |

The integration of single-cell transcriptomic atlases, lineage-tracing, and quantitative niche analysis has unequivocally established progenitor cell depletion as a central driver of thymic involution. The problem is multi-compartmental, involving an early decline in bone marrow lymphoid progenitors, a quiescence of intrathymic stromal precursors, and the emergence of dysfunctional cell states that actively disrupt the regenerative microenvironment. Future therapeutic strategies must move beyond general stromal rejuvenation and instead adopt a targeted, progenitor-centric approach. This includes developing methods to expand the pre-thymic progenitor pool, reprogramming aaTECs to a functional state, and therapeutically reactivating quiescent TEC progenitors. Success in these endeavors will be critical for restoring robust immune function in the elderly, improving vaccine responses, and mitigating cancer incidence.

Fibroblast Expansion and Adipogenesis in Aging Thymic Microenvironment

The aging thymic microenvironment undergoes a profound functional decline characterized by large-scale tissue remodeling. A hallmark of this process, known as thymic involution, is the expansion of fibroblastic stromal cells and their subsequent differentiation into adipocytes, which progressively replaces the functional tissue with fat. This transformation disrupts the specialized niches required for T-cell development, compromising adaptive immunity in aged individuals. Recent single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) studies have elucidated the cellular players and molecular drivers behind this phenomenon, revealing key roles for specific signaling pathways and transcriptional regulators. This whitepaper synthesizes current mechanistic insights into fibroblast expansion and adipogenesis within the aging thymus, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to develop therapeutic interventions for thymic rejuvenation.

The thymus is the primary lymphoid organ responsible for the generation and selection of a diverse, self-tolerant T-cell repertoire. Age-related thymic involution is one of the most prominent features of immunological aging, characterized by a progressive reduction in thymic epithelial space, decreased naïve T-cell output, and consequent impaired adaptive immunity [22] [2]. This process begins early in life and leads to the substantial replacement of functional thymic parenchyma with adipose tissue by middle age [23]. While thymic involution has long been recognized histologically, the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms have remained poorly understood until the recent application of high-resolution transcriptomic technologies. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) atlases of human and mouse thymus across ages now provide unprecedented resolution of the dynamic changes in thymic stromal composition and cell states during aging [22] [21] [2]. These studies consistently identify the expansion of fibroblastic populations and adipogenic differentiation as central drivers of thymic involution, revealing potential therapeutic targets for mitigating immunosenescence.

Cellular Dynamics of the Aging Thymic Microenvironment

Key Cellular Transitions Revealed by Single-Cell Atlas

scRNA-seq profiling of aging thymus has delineated the specific cellular transformations that underlie the adipose accumulation observed during involution. The thymic stromal compartment, particularly thymic mesenchymal stromal cells (tMSCs), exhibits a markedly increased propensity for adipocyte differentiation compared to MSCs from other sources [23]. This population expands in aged mice and humans, serving as the primary source of lipid-laden adipocytes that characterize the involuted thymus [23] [22]. Concurrently, the thymic epithelial cell (TEC) compartment, essential for T-cell development and selection, undergoes significant depletion and transcriptional alteration [2]. Fibroblast expansion occurs alongside these changes, with distinct fibroblast subpopulations emerging during aging, including those expressing chondrocyte-lineage markers and pro-adipogenic traits [24] [21].

Table 1: Cellular Composition Changes in Aging Thymic Microenvironment

| Cell Type | Change with Aging | Functional Consequences | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thymic MSCs (tMSCs) | Expansion with increased adipogenic potential | Primary source of thymic adipocytes; drives fatty replacement | [23] |

| Cortical TECs (cTECs) | Significant depletion | Impaired thymocyte positive selection | [2] |

| Medullary TECs (mTECs) | Depletion with altered promiscuous gene expression | Compromised self-tolerance induction | [2] |

| Thymic Fibroblasts | Expansion with altered phenotypes | ECM remodeling, adipogenic support | [24] [21] |

| Adipocytes | Substantial accumulation | Disruption of thymic architecture and function | [23] [22] |

Functional Consequences for T-Cell Development

The stromal transformations in the aging thymus directly impair its capacity to support T-cell development. Aged thymic microenvironments exhibit reduced T-lineage potential in early thymic progenitors and diminished representation of tissue-restricted antigens, which is crucial for establishing self-tolerance [22] [2]. Negative selection of self-reactive thymocytes becomes less efficient, particularly in the medullary compartment, potentially allowing autoreactive T cells to escape into the periphery [2]. These functional deficits correlate with an altered T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire in aged individuals, characterized by shifts in diversity and expanded virus-specific T-cell clonotypes [22]. The accumulation of lipid-laden adipocytes within the aging thymic parenchyma physically disrupts the delicate stromal-thymocyte interactions necessary for efficient T-cell development and selection.

Molecular Drivers of Thymic Adipogenesis

Key Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

The adipogenic transformation of the thymic microenvironment is orchestrated by specific molecular pathways that have been elucidated through recent studies:

Figure 1: MRAP-Mediated Adipogenesis Pathway in Thymic MSCs. Thymosin-α1 promotes MRAP expression through FoxO1 signaling, driving adipogenic differentiation.

The melanocortin-2 receptor accessory protein (MRAP) has been identified as a critical driver of adipocyte differentiation in thymic mesenchymal stromal cells (tMSCs) [23]. Thymosin-α1, a naturally occurring thymic peptide, promotes MRAP expression through the FoxO1 signaling pathway, creating a molecular cascade that activates the master adipogenic transcription factors PPARγ and CEBPα [23]. This MRAP-mediated adipogenesis is specific to thymic stromal cells, which exhibit significantly higher basal MRAP expression compared to MSCs from other sources such as dental pulp [23]. Genetic ablation of MRAP in mouse models substantially reduces thymic adipogenesis, confirming its essential role in this process [23].

Beyond the MRAP pathway, additional regulatory networks contribute to the aging-associated remodeling of the thymic microenvironment. The transcriptional regulator IGFBP5 (Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 5) is upregulated in aging thymic epithelial cells and is associated with the promotion of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and adipogenesis processes [21]. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling, particularly FGF2 derived from adipocytes, induces a chondrocyte-like state in neural fibroblasts during peripheral nerve aging, a process that may have parallels in thymic stromal aging [24]. These pathways collectively drive the functional decline of the thymic epithelium while simultaneously promoting the adipogenic transformation of the stromal compartment.

Table 2: Key Molecular Regulators of Thymic Adipogenesis

| Molecule/Pathway | Role in Thymic Aging | Mechanistic Insight | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRAP | Master regulator of tMSC adipogenesis | Required for PPARγ/CEBPα activation in response to thymosin-α1 | siRNA knockdown reduces adipogenesis; Mrap-/- mice show impaired thymic involution [23] |

| Thymosin-α1 | Inducer of adipogenic program | Signals through FoxO1 to increase MRAP expression | Promotes adipocyte differentiation in human and mouse tMSCs [23] |

| IGFBP5 | Promotes EMT and adipogenesis | Upregulated in aging TECs; correlates with stromal expansion | Increased protein expression in human and mouse aging thymus; knockdown affects thymocyte proliferation [21] |

| FGF Signaling | Induces aberrant fibroblast states | FGF2 from adipocytes promotes chondrocyte-like fibroblast transition | FGF2 induces SOX9/FOXC2 in human perineurial fibroblasts; blocked by FGF1 [24] |

Metabolic Reprogramming in Aged Stromal Cells

Aging thymic stromal cells undergo significant metabolic reprogramming that supports their phenotypic transformation. Similar to observations in dermal fibroblasts during skin aging, thymic stromal cells likely shift toward increased fatty acid oxidation and reduced glycolysis [25]. This metabolic switch may be driven by the expanded adipose tissue within the aging thymus, which releases free fatty acids into the extracellular space that can be taken up by adjacent stromal cells via fatty acid transporters such as CD36 [25]. The resulting metabolic reprogramming influences the cellular phenotype of thymic stromal cells, promoting the acquisition of pro-adipogenic traits and reducing the expression of extracellular matrix genes characteristic of functional stromal niches [25]. This creates a feed-forward cycle wherein initial adipocyte deposition promotes further metabolic reprogramming of stromal cells, accelerating the involution process.

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Thymic Adipogenesis

Key Methodologies and Workflows

The investigation of fibroblast expansion and adipogenesis in the aging thymic microenvironment employs several specialized experimental approaches:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Thymic Adipogenesis Research. Key steps from tissue processing to molecular analysis.

Isolation and Characterization of Thymic Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (tMSCs)

tMSCs are isolated from thymic tissue through sequential enzymatic dissociation and culture, allowing for the depletion of thymocytes and enrichment of stromal populations [23]. The purity of tMSC preparations is confirmed by flow cytometric exclusion of contaminating populations (TECs, fibroblasts, immune cells) using specific markers: Aire⁻Ly51⁻EpCAM⁻MHCⅡ⁻CD86⁻CD40⁻ [23]. True tMSCs express typical MSC surface markers (CD29, CD105, Sca-1) while lacking hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45) [23]. Functional characterization includes demonstration of their immunosuppressive capacity through T-cell suppression assays and evaluation of their differentiation potential using adipogenic and osteogenic culture conditions [23].

Adipogenic Differentiation Assays

For in vitro adipogenesis studies, tMSCs are cultured in adipogenic differentiation medium containing standard adipogenic inducers [23]. Successful differentiation is quantified through multiple methods: (1) Oil Red O staining to visualize lipid vesicle accumulation; (2) Quantitative RT-PCR to measure expression of adipogenic genes (PPARγ, CEBPα, Fabp4); (3) Immunofluorescence or Western blot for adipocyte-specific proteins (FABP4) [23]. The adipogenic potential of tMSCs is often compared to MSCs from other sources (e.g., dental pulp) to demonstrate thymus-specific characteristics [23]. Genetic manipulation through siRNA-mediated knockdown (e.g., targeting MRAP) or CRISPR/Cas9 approaches establishes the functional requirement of specific factors in the adipogenic process [23].

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing and Computational Analysis

scRNA-seq provides comprehensive profiling of cellular heterogeneity in the aging thymic microenvironment. Standard protocols involve: (1) Quality control filtering to remove low-quality cells and doublets; (2) Normalization and integration of multiple datasets using algorithms like BBKNN or Harmony to correct for batch effects; (3) Dimensionality reduction (UMAP) and clustering (Leiden algorithm) to identify distinct cell populations; (4) Differential expression analysis to define cluster-specific markers; (5) Cell-cell communication analysis using tools like CellChat to infer intercellular signaling networks; (6) Gene regulatory network reconstruction with SCENIC to identify key transcription factors [22] [21]. Integration of data from multiple age points enables the tracking of population dynamics and transcriptional changes across the aging process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Thymic Adipogenesis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application/Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Surface Markers | CD29, CD105, Sca-1 (positive); CD34, CD45 (negative) | Identification and purification of tMSCs | Used in combination to distinguish tMSCs from thymic fibroblasts and TECs [23] |

| Adipogenic Differentiation Media | Standard adipogenic inducers (IBMX, dexamethasone, insulin, indomethacin) | Induction of adipocyte differentiation from tMSCs | tMSCs show stronger adipogenic response compared to osteogenic differentiation [23] |

| Staining Reagents | Oil Red O, FABP4 antibodies, SA-β-Gal | Detection of lipid accumulation, adipocyte markers, and senescent cells | Oil Red O staining quantifies lipid vesicle formation; FABP4 confirms adipocyte maturity [23] |

| Genetic Manipulation Tools | MRAP siRNA, CRISPR/Cas9 for Mrap knockout | Functional validation of key regulators | MRAP knockdown significantly reduces adipogenic gene expression and lipid accumulation [23] |

| scRNA-seq Platforms | 10X Genomics, SMART-Seq2 | Single-cell transcriptomic profiling | Enables identification of novel cell states and population dynamics during aging [22] [21] [2] |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The molecular insights into thymic adipogenesis provide promising avenues for therapeutic intervention to counteract thymic involution and restore immune competence in aged individuals. Several strategic approaches emerge from recent findings:

Targeting the MRAP-Adipogenesis Axis

Inhibition of MRAP function or its upstream regulators represents a promising strategy to slow thymic adipogenesis. The MRAP-mediated pathway is particularly attractive as it appears to be specifically important for thymic adipogenesis rather than systemic lipid metabolism [23]. Small molecule inhibitors targeting the FoxO1 signaling pathway could potentially interrupt the thymosin-α1-MRAP adipogenic cascade, preserving thymic stroma and function [23]. Alternatively, targeting the FGF signaling axis with specific FGF1-based therapeutics might prevent the aberrant fibroblast activation that contributes to thymic microenvironment deterioration [24].

Senotherapy and Metabolic Modulation

Given the accumulation of senescent cells in aged thymic tissue, senolytic therapies that selectively eliminate senescent stromal cells represent another promising approach [26]. The dysregulated metabolic state of aged stromal cells, characterized by increased fatty acid oxidation, might be targeted through metabolic modulators that shift cells toward a more glycolytic, synthetically active phenotype [25]. Such metabolic reprogramming could potentially reverse some age-related phenotypic changes in thymic fibroblasts and epithelial cells, preserving their supportive functions for T-cell development.

The integration of single-cell technologies with functional validation studies continues to refine our understanding of the complex cellular interactions within the aging thymic microenvironment. Future research directions should focus on spatial transcriptomics to precisely map cellular relationships, lineage tracing to definitively establish cellular transitions, and humanized models to validate therapeutic targets. By targeting the specific mechanisms driving fibroblast expansion and adipogenesis, interventions to maintain or restore thymic function throughout life represent a promising frontier for addressing age-related immune decline.

Cell-Cell Communication Changes in Thymic Crosstalk During Aging

The thymus is a primary lymphoid organ essential for the production of a diverse and self-tolerant T-cell repertoire. Its function is governed by a dynamic, reciprocal communication network between developing thymocytes and the stromal microenvironment, a process termed thymic crosstalk [16] [21]. This process defines the unique ability of the thymic microenvironment to coordinate T-cell development and establish central tolerance [16]. However, the thymus undergoes progressive, age-related functional decline and structural atrophy, known as involution, a hallmark of immune aging [6] [27]. This involution leads to diminished naïve T-cell output, a constricted T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire, and reduced immune competence, contributing significantly to the broader phenomenon of immunosenescence [27]. Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics have begun to deconstruct the thymic microenvironment at unprecedented resolution, revealing that age-related degeneration is not a passive process but involves active, pathological alterations in cell states and communication networks [6] [7] [16]. This technical review synthesizes current evidence from single-cell atlas research to delineate the specific disruptions in thymic crosstalk during aging, providing a mechanistic framework for understanding immune aging and identifying potential therapeutic targets.

Key Cellular and Molecular Alterations in the Aging Thymic Microenvironment

Aging reshapes the thymus at the cellular and molecular levels. The table below summarizes the core cell populations, their functional changes, and key molecular drivers identified through single-cell studies.

Table 1: Key Cellular and Molecular Alterations in the Aging Thymic Microenvironment

| Cell Population | Primary Change with Aging | Key Molecular Regulators/Functions | Impact on Thymic Crosstalk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thymic Epithelial Cells (TECs) | Emergence of atypical states (aaTECs); overall decline in numbers, particularly mTECs [6]. | ↓ FOXN1 [6] [21]; ↑ Features of EMT; ↑ IGFBP5 [21]. | Disrupted stromal scaffold; impaired positive/negative selection; altered cytokine signaling. |

| Atypical TECs (aaTECs) | Formation of high-density, thymocyte-devoid peri-medullary clusters; significant expansion post-injury [6]. | Acts as a "sink" for trophic factors (e.g., FGF, BMP); downregulation of AIRE [6]. | Sequesters essential regeneration signals, perturbing communication and limiting regenerative capacity. |

| Fibroblasts (FBs) | Transcriptional shift towards pro-inflammatory or "inflammaging" programs [6]. | Upregulation of programs associated with inflammaging [6]. | Promotes a degenerative tissue environment; may disrupt TEC-thymocyte interactions. |

| Thymocytes | Reduced cellularity and altered developmental dynamics [6] [7]. | Altered NOTCH, IL-7, and CXCL12 signaling [21]. | Compromised "thymic crosstalk," failing to provide necessary signals for TEC maturation and maintenance. |

| Endothelial Cells (ECs) | Relative stability in population size [6]. | Potential changes in Bmp4 expression (produced by vECs) [6]. | May affect progenitor entry and intrathymic migration cues. |

Dysregulated Signaling Pathways and Intercellular Communication

The cellular alterations in the aged thymus are underpinned by specific dysregulations in critical signaling pathways that mediate intercellular communication.

Table 2: Key Signaling Pathways Dysregulated in Thymic Aging

| Signaling Pathway | Primary Function in Thymus | Change with Aging | Key Interacting Cell Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| FGF & BMP Signaling | Trophic support, epithelial regeneration, and homeostasis [6]. | Diverted/sequestered by aaTECs [6]. | TEC → TEC; Mesenchyme → TEC. |

| TNFSF (e.g., RANK/RANKL) | Mediates crosstalk for mTEC differentiation and maturation [16]. | Likely impaired due to loss of mTECs and thymocyte defects. | Thymocytes/LTIs → TEC. |

| NOTCH Signaling | Drives T-cell lineage commitment and specification [21]. | Signaling patterns change completely [21]. | TEC → Thymocyte. |

| IL-7 Signaling | Boosts expansion of early T lineage progenitors [21]. | Signaling patterns change completely [21]. | TEC → Thymocyte. |

| CCL21/CCL19-CCR7 | Guides progenitor and thymocyte migration within the thymus [16]. | Likely disrupted due to stromal disorganization. | TEC/Stroma → Thymocyte. |

Large-scale atlas studies, such as those using the scDiffCom tool, have quantified these changes across tissues, revealing that aging is associated with a widespread upregulation of immune and inflammatory processes and a downregulation of developmental pathways, extracellular matrix organization, and angiogenesis within stromal compartments [28].

Diagram 1: Signaling pathway dysregulation in thymic aging. The diagram illustrates how the emergence of aaTECs and the inflammaging fibroblast state disrupts the trophic and developmental signaling essential for maintaining thymic function and thymocyte development.

Experimental Approaches for Analyzing Age-Related Changes

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) Workflow

This protocol outlines the process for generating and analyzing single-cell data from young and aged thymic tissue to investigate cell-cell communication.

1. Tissue Processing and Single-Cell Suspension Preparation:

- Tissue Collection: Obtain thymic tissues from donors of different age groups (e.g., young adult vs. aged). Human tissues should be collected with ethical approval and informed consent [21].

- Cell Dissociation: Mechanically dissociate the tissue and use enzymatic cocktails (e.g., collagenase/DNase mix) to generate a single-cell suspension while preserving cell viability and surface markers [6].

- Stromal Cell Enrichment: For in-depth stromal analysis, negatively select or deplete hematopoietic lineage (CD45+) cells using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to enrich for CD45− stromal cells (TECs, endothelial cells, fibroblasts) [6].

2. Single-Cell Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Platform Selection: Use a platform such as 10x Genomics for high-throughput droplet-based scRNA-seq [21].

- Library Construction: Generate barcoded scRNA-seq libraries according to the manufacturer's protocol. For enhanced cell type identification, consider integrating CITE-seq (Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing) to simultaneously measure surface protein expression [7].

- Sequencing: Sequence libraries on an Illumina platform to a sufficient depth (e.g., 50,000 reads per cell).

3. Computational Data Analysis:

- Quality Control and Preprocessing: Use tools like Scanpy or Seurat to filter out low-quality cells, doublets, and cells with high mitochondrial gene content [21]. Normalize the data and identify highly variable genes.

- Batch Effect Correction and Integration: Apply integration algorithms such as BBKNN, Harmony, or scVI to correct for technical variations between samples from different ages, donors, or sequencing batches [21] [29].

- Cell Clustering and Annotation: Perform dimensionality reduction (PCA, UMAP) and cluster cells using graph-based methods (Leiden algorithm). Annotate cell clusters using canonical marker genes [6] [21].

- Differential Communication Analysis: Utilize specialized R packages like scDiffCom to perform a statistical differential analysis of ligand-receptor interactions between age conditions. The tool relies on a curated database of ~5,000 ligand-receptor pairs to identify significant changes in intercellular communication [28].

Spatial Transcriptomics and Multiplexed Imaging

To contextualize single-cell findings within tissue architecture, spatial transcriptomic and proteomic approaches are critical.

1. Spatial Transcriptomics (10x Visium):

- Tissue Preparation: Cryosection fresh-frozen thymus tissue onto Visium slides and perform H&E staining.

- Library Preparation: Follow the Visium spatial gene expression protocol to capture transcriptomic data from tissue sections.

- Data Integration: Use computational frameworks like TissueTag to align spatial data with scRNA-seq references. TissueTag enables the construction of a Common Coordinate Framework (CCF), such as the Cortico-Medullary Axis (CMA), which quantifies the position of each spot or cell relative to morphological landmarks (capsule, cortex, medulla) [7]. This allows for the analysis of gene expression gradients and cell localization along a continuous tissue axis.

2. Multiplexed Protein Imaging (IBEX):

- Antibody Panel Design: Design a panel of antibodies targeting key proteins of interest for thymic stroma and immune cells.

- Cyclical Staining and Imaging: Perform iterative cycles of antibody staining, imaging, and fluorophore inactivation on the same tissue section using platforms like IBEX.

- Image Analysis and Cell Segmentation: Segment cells based on nuclear and cytoplasmic markers. Extract mean protein expression levels per cell and integrate with spatial coordinates [7].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for thymus aging atlas. The workflow integrates single-cell and spatial omics technologies with computational analysis to build a comprehensive model of age-related changes in thymic crosstalk.

The following table details essential reagents, datasets, and computational tools for research in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Thymic Aging Studies

| Category | Resource | Description and Function |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | scDiffCom [28] | An R package for differential intercellular communication analysis between two conditions (e.g., young/old) from scRNA-seq data. |

| TissueTag & OrganAxis [7] | A Python package for constructing a Common Coordinate Framework (CCF) for spatial data, enabling cross-sample and cross-modality integration. | |

| ThymoSight [6] | An online tool (www.thymosight.org) that integrates published thymic scRNA-seq datasets for interrogation and comparison. | |

| Curated Molecular Databases | Ligand-Receptor Pair Database [28] | A collection of ~5,000 curated ligand-receptor interactions compiled from seven public resources for ICC analysis. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | 10x Visium [7] | A commercial platform for capturing genome-wide expression data from intact tissue sections, preserving spatial context. |

| Multiplexed Protein Imaging | IBEX [7] | An iterative staining and imaging method that enables highly multiplexed protein detection (40+ markers) in a single tissue section. |