Decoding Tissue Immunity: Insights from Human Postmortem Studies

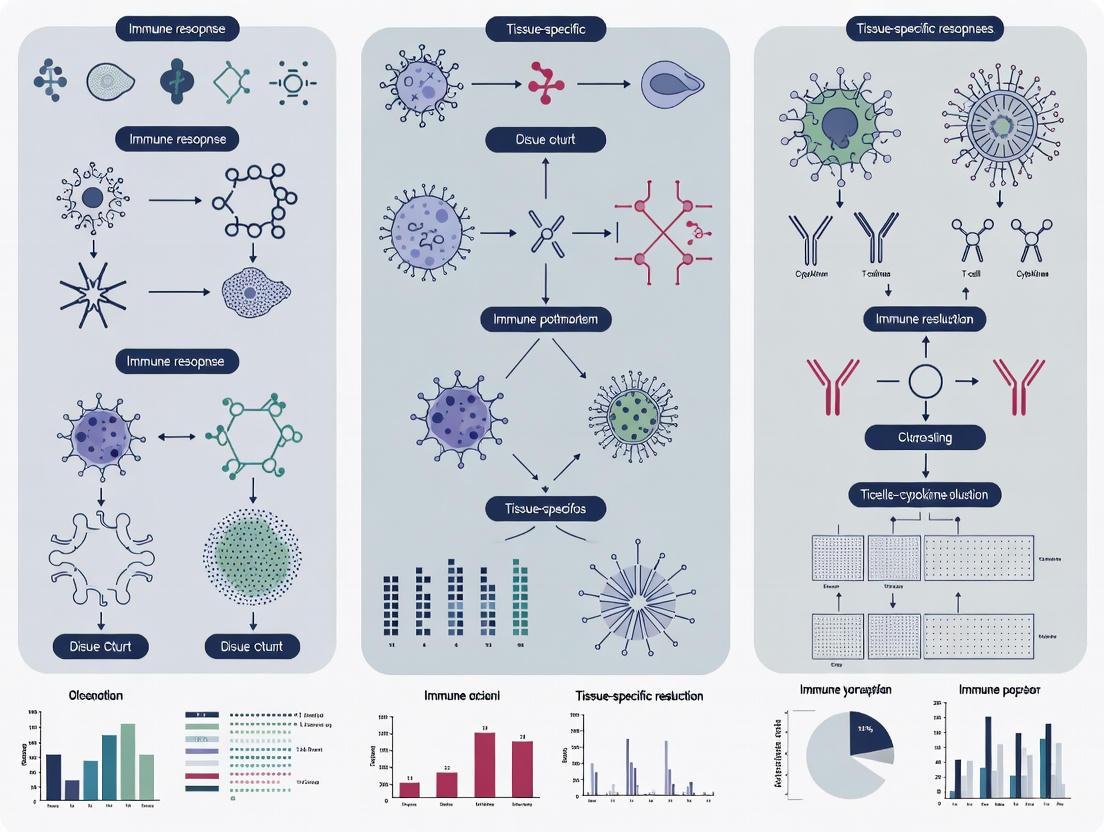

This article synthesizes recent advances in our understanding of tissue-specific immune responses, with a particular focus on insights gained from human postmortem studies.

Decoding Tissue Immunity: Insights from Human Postmortem Studies

Abstract

This article synthesizes recent advances in our understanding of tissue-specific immune responses, with a particular focus on insights gained from human postmortem studies. It explores the foundational principles of localized immunity, detailing the critical roles of tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) and other specialized populations. The content covers cutting-edge methodological approaches, including multi-color flow cytometry and AI-driven single-cell RNA sequencing, for analyzing immune cells within their native tissue context. It further addresses the unique challenges and optimization strategies in postmortem tissue research, and provides a comparative analysis of how this human-based evidence validates or challenges findings from animal models. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review highlights the translational potential of these findings for vaccine design, cancer immunotherapy, and the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.

The Landscape of Localized Defense: Principles of Tissue-Specific Immunity

The immune system employs a dynamic network of cells distributed throughout the body to defend against infections, regulate inflammation, and repair tissue damage. Within this network, tissue-resident immune cells (TRICs) constitute a specialized compartment that resides within specific tissues without recirculating, forming a critical first line of defense and playing essential roles in maintaining tissue homeostasis [1]. Unlike their circulating counterparts, TRICs are endowed with distinct capabilities shaped by their local tissue environments, allowing for highly specialized immune surveillance and response [1]. Recent advances in single-cell technologies and human tissue studies have revolutionized our understanding of TRIC heterogeneity, development, and function across different organs. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to defining tissue-resident immune cells, with a specific focus on their characteristics, research methodologies, and implications for human postmortem studies within the context of tissue-specific immune responses.

Defining Characteristics and Classification of TRICs

Core Definition and Key Properties

Tissue-resident immune cells are defined by their persistent localization within specific tissues without re-entering the circulation under steady-state conditions [1]. This fundamental characteristic distinguishes them from circulating leukocytes and endows them with unique functional capabilities. The residency of TRICs is maintained through complex interactions with local tissue niches and expression of specific retention molecules that inhibit their egress into lymphatic or blood vessels [1].

Key defining properties of TRICs include:

- Long-term tissue persistence: TRICs can reside in tissues for extended periods, in some cases throughout the lifespan of the organism.

- Limited recirculation: Unlike circulating immune cells, TRICs do not routinely traffic through blood or lymphatic vessels.

- Tissue-specific adaptation: TRICs undergo phenotypic and functional reprogramming to meet the specific demands of their tissue environment.

- Self-renewal capacity: Many TRIC populations maintain themselves through local proliferation rather than continuous replacement from circulating precursors.

Major TRIC Populations and Their Markers

TRICs encompass multiple lineages from both innate and adaptive immunity. The table below summarizes the major TRIC populations, their key identifying markers, and primary tissue distributions based on recent multimodal profiling studies [2] [1].

Table 1: Major Tissue-Resident Immune Cell Populations and Their Characteristics

| TRIC Population | Key Surface Markers | Transcription Factors | Primary Tissue Locations | Main Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) | CD69, CD103, CD49a | Blimp1, Hobit, Runx3 | Skin, lung, intestine, liver [2] | Rapid local protection, cytokine production |

| Tissue-resident macrophages | F4/80, CD11b (variable), TIMD4, LYVE1 | Ahr, Nfatc1, Nfatc2, Irf9 [3] | Kidney, liver, brain, lung [4] [3] | Phagocytosis, tissue repair, homeostasis |

| Tissue-resident B cells (BRM) | CD69, CD73 | Not specified | Lung, intestine [1] | Local antibody production |

| Tissue-resident NK cells (trNK) | CD49a, CD69, CD103 | T-bet, Eomes | Liver, salivary gland, uterus [1] | Cytokine production, cytotoxicity |

| Tissue-resident ILCs | CD127, CD161, CD69 | GATA3, RORγt, T-bet | Mucosal tissues, liver [2] | Tissue repair, cytokine production |

| Tissue-resident neutrophils (TRN) | CD11b, Ly6G | Not specified | Spleen, lung [1] | Pathogen clearance, immunoregulation |

The expression of canonical tissue-residency markers varies significantly across different tissue environments. For instance, CD103 is predominantly expressed by TRICs in mucosal tissues, while CD69 and/or CD49a are more commonly expressed in non-mucosal tissues [1]. This heterogeneity reflects the remarkable adaptability of TRICs to their local microenvironment.

Table 2: Tissue-Specific Variations in Human TRIC Populations Based on Multimodal Profiling

| Tissue Site | Dominant TRIC Populations | Tissue-Specific Features |

|---|---|---|

| Lung (BAL/parenchyma) | Alveolar macrophages, CD8+ TRM, CD4+ TRM [2] | Enhanced disease tolerance mechanisms [4] |

| Jejunum (epithelium/lamina propria) | CD8+ TRM, CD4+ TRM, ILC1, ILC3 [2] | High CD103 expression, IgA+ plasma cells [2] |

| Kidney | TLF+ macrophages (TIMD4+ LYVE1+ FOLR2+) [3] | CX3CR1/CX3CL1 axis for maintenance [3] |

| Skin | CD8+ TRM, γδ T cells, Langerhans cells [1] | CD49a expression predominates over CD103 [1] |

| Lymphoid organs | TRM, resident B cells, macrophages | CD69+ memory B cells, MHC IIhi macrophages [2] |

Origins, Development, and Maintenance

Developmental Origins of TRICs

TRICs originate through diverse developmental pathways that vary by cell lineage and tissue location. The schematic below illustrates the major developmental origins of different TRIC populations:

Figure 1: Developmental origins of major TRIC populations. TRICs can originate from embryonic precursors, adult hematopoietic stem cells, or circulating immune cells that acquire tissue-resident properties.

Some TRICs, including certain tissue-resident macrophages and mast cells, trNK cells, tissue-resident ILCs, and γδ T cells, establish tissue residency during embryogenesis [1]. For example, kidney TRMs (KTRMs) originate from both embryonic yolk sac erythro-myeloid progenitors and the fetal liver, demonstrating the capacity for self-renewal independent of bone marrow hematopoiesis [3]. In contrast, other TRICs such as tissue-resident memory T (TRM) and B (BRM) cells postnatally establish tissue residency during effector phases of immune responses [1].

Maintenance Mechanisms

The maintenance of TRIC populations in tissues involves both self-renewal and limited replenishment from circulating precursors. Tissue-resident macrophages and ILCs predominantly maintain themselves through local self-renewal, with varying requirements for bone marrow-derived progenitor input across different tissues [1]. For instance, alveolar macrophages in the lung and microglia in the brain are primarily self-maintaining, while certain intestinal macrophage populations require continuous replacement from circulating monocytes [4].

Key maintenance mechanisms include:

- CX3CR1/CX3CL1 axis: Critical for maintaining kidney TRMs through in situ proliferation [3].

- IL-4 signaling: Promotes self-renewal and accumulation of TRMs [3].

- Fatty acid metabolism: Mediated by FABP5, essential for differentiation of bone marrow-derived TRMs into KTRMs [3].

- Local tissue niches: Provide specific signals that support TRIC survival and function.

Research Methodologies for TRIC Investigation

Experimental Approaches for Identifying TRICs

Several specialized methodologies have been developed to identify and characterize TRICs, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Parabiosis surgery remains the gold standard for identifying TRICs, where the circulatory systems of two genetically identical mice are surgically joined. Circulating cells establish equilibrium in both mice, while tissue-resident cells do not exchange between partners [1]. This approach has identified TRM cells, ILCs, trNKs, BRM cells, tissue-resident macrophages, tissue-resident iNKT, MAIT cells, and TRNs [1].

Intravascular labeling employs fluorescently conjugated antibodies administered intravenously to distinguish blood-borne cells (which are labeled) from tissue-resident cells (which remain unlabeled) [1]. This method is particularly useful for identifying TRM and BRM cells without requiring surgical procedures.

Advanced single-cell technologies including scRNA-seq and CITE-seq (Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes) enable comprehensive profiling of TRIC phenotypes and functions across tissues [2] [1]. These approaches have revealed remarkable heterogeneity in TRIC populations across different tissue sites and have identified novel TRIC subsets in both homeostatic and disease conditions.

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Parabiosis Protocol for TRIC Identification

Surgical procedure: Select age- and sex-matched mice with compatible CD45 alleles (e.g., CD45.1 and CD45.2). Anesthetize mice and shave their lateral aspects. Make matching skin incisions from elbow to knee joint on each mouse. Join the olecranon and knee joints using suture material. Sutures the dorsal and ventral skin flaps to complete the union.

Post-operative care: Administer analgesics for 72 hours and antibiotics for 7-10 days. Allow 2-4 weeks for circulatory exchange to reach equilibrium before experiments.

Analysis: Harvest tissues of interest and prepare single-cell suspensions. Analyze cell populations by flow cytometry using CD45 allelic markers to distinguish host-derived (tissue-resident) from partner-derived (circulatory) cells.

Interpretation: TRICs are identified as cells predominantly derived from the host mouse, with minimal contribution from the parabolic partner.

Intravascular Staining Protocol

Antibody preparation: Dilute fluorescently conjugated anti-CD45 antibody or other pan-leukocyte markers in sterile PBS. Typically, 2-5 µg of antibody in 100-200 µL volume is administered intravenously.

Administration: Inject antibody solution via the tail vein or retro-orbital sinus. Allow 3-5 minutes for circulation to ensure complete labeling of blood cells.

Perfusion and tissue collection: Euthanize mice and perfuse extensively with 20-30 mL of PBS through the left ventricle to flush out blood vessels. Harvest tissues of interest and process for flow cytometry.

Analysis: Identify intravascular (labeled) versus tissue-resident (unlabeled) leukocytes by flow cytometry.

Multimodal Single-Cell Profiling Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for multimodal TRIC characterization using CITE-seq:

Figure 2: CITE-seq workflow for multimodal TRIC profiling. This approach simultaneously captures transcriptomic and proteomic data from single cells.

Human Postmortem Studies for TRIC Research

Postmortem tissue studies provide a unique opportunity to investigate human TRICs across multiple organs from individual donors. A recent study demonstrated the feasibility of this approach for tuberculosis research, establishing that postmortem procedures and tissue processing could be completed within 8 hours of death while maintaining cell viability for up to 14 hours [5]. This work found good acceptance from next-of-kin for tissue donation, providing a valuable resource for understanding tissue-specific immune responses in humans.

Key considerations for postmortem TRIC studies:

- Time window: Process tissues within 8 hours of death for optimal cell viability.

- Tissue processing: Use established protocols for mononuclear cell isolation from multiple tissues [2].

- Multimodal profiling: Combine CITE-seq with scRNA-seq for comprehensive TRIC characterization.

- Data integration: Leverage computational tools like multi-resolution variational inference (MrVI) to harmonize variation between cell states across samples [2].

Signaling Pathways and Functional Programs

Key Signaling Pathways in TRIC Biology

TRIC development, maintenance, and function are regulated by specific signaling pathways and metabolic programs. Recent studies using quantitative signal transduction pathway activity profiling have revealed characteristic pathway activation patterns in different immune cell types [6].

Table 3: Key Signaling Pathways in TRIC Biology and Their Functions

| Signaling Pathway | Key Components | Role in TRICs | Experimental Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| CX3CR1/CX3CL1 | CX3CR1, CX3CL1 | Maintenance of kidney TRMs through in situ proliferation [3] | Flow cytometry, scRNA-seq |

| TGF-β signaling | TGF-β, SMADs | Induction of CD103 expression on TRMs [1] | STAP-STP technology, phospho-flow [6] |

| Fatty acid metabolism | FABP5, PPARs | Differentiation of bone marrow-derived TRMs [3] | Metabolic profiling, inhibitor studies |

| JAK-STAT signaling | JAKs, STAT1/2, STAT3 | TRM development and function [6] | STAP-STP technology, phospho-flow [6] |

| PI3K-FOXO signaling | PI3K, FOXO | Regulation of TRIC survival and metabolism [6] | STAP-STP technology [6] |

| Type 1 IFN signaling | IFNAR, STAT1/2 | Establishment of trained immunity in alveolar macrophages [4] | STAP-STP technology, inhibitor studies [6] |

Trained Innate Immunity in Tissue-Resident Macrophages

Tissue-resident macrophages can develop trained innate immunity (TII), representing a form of innate immune memory characterized by long-lasting functional modifications following initial immunological exposure [4]. This training involves epigenetic reprogramming and metabolic rewiring that enhances responsiveness to subsequent challenges.

Key features of trained immunity in TRICs:

- Duration: Persistent modifications that outlast the initial stimulus.

- Mechanisms: Epigenetic changes and metabolic reprogramming.

- Specificity: Can enhance responses to heterologous challenges.

- Outcomes: Either protective (enhanced pathogen clearance) or maladaptive (exacerbated inflammation).

The schematic below illustrates the induction and maintenance of trained immunity in tissue-resident macrophages:

Figure 3: Induction and maintenance of trained immunity in tissue-resident macrophages. Initial exposure to immunological stimuli triggers epigenetic and metabolic changes that establish a long-lasting trained state.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for TRIC Investigation

| Reagent/Platform | Specific Examples | Application in TRIC Research |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody panels | 24-color flow cytometry panels [5] | Comprehensive immunophenotyping of human TRICs |

| Cell isolation kits | Tissue dissociation systems | Isolation of viable immune cells from multiple tissues |

| Single-cell platforms | 10X Genomics, CITE-seq | Multimodal profiling of TRIC transcriptomes and surface proteins [2] |

| Cell culture systems | 3D full-thickness skin models [5] | Study of TRIC function in tissue-like environments |

| Computational tools | MrVI, MMoCHi classifier [2] | Data integration and cell annotation for multimodal datasets |

| Signal transduction assays | STAP-STP technology [6] | Quantitative measurement of pathway activity in immune cells |

| In vivo models | Parabiosis surgery, intravascular staining [1] | Definitive identification of tissue-resident versus circulating cells |

| Microneedle patches | Hydrogel-coated MN arrays [7] | Minimally invasive sampling of skin TRICs |

| 5-Oxodecanoic acid | 5-Oxodecanoic acid, CAS:624-01-1, MF:C10H18O3, MW:186.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Benzoylacetone | Benzoylacetone, CAS:93-91-4, MF:C10H10O2, MW:162.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Technologies and Model Systems

Immune organoid systems have emerged as powerful tools for studying human immune responses in vitro. These systems provide sophisticated insights about tissue architecture and functionality in miniaturized organs, overcoming limitations of animal models that inadequately represent complex human-specific interactions [8]. Immune organoids established from patient-derived lymphoid tissues can reflect human adaptive immunity with more physiologically relevant aspects than traditional models [8].

Microneedle (MN) patch technology provides a minimally invasive approach to sample immune cells and soluble factors from the skin [7]. Recent advancements include hydrogel-coated MN patches that can recover thousands of live antigen-specific lymphocytes as well as innate immune cells from skin sites where TRMs have been restimulated [7]. This technology is particularly valuable for longitudinal monitoring of TRIC responses in human subjects.

Humanized mouse models and multiorgan-on-chip systems are being developed to better recapitulate human immune responses. These advanced platforms enable study of systemic immunological processes by integrating various immune cells and tissues in a controlled in vitro environment [5].

Tissue-resident immune cells represent a critical component of the immune system, with specialized functions tailored to specific tissue environments. The definitive identification and characterization of TRICs requires specialized methodologies, including parabiosis, intravascular staining, and multimodal single-cell profiling. Recent advances in single-cell technologies, human postmortem studies, and engineered model systems have dramatically expanded our understanding of TRIC heterogeneity, development, and function across different tissues. The integration of these approaches provides unprecedented opportunities to investigate human tissue-specific immune responses and develop targeted therapeutic strategies that leverage the unique properties of TRICs. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly yield further insights into the complex roles of TRICs in health and disease, potentially revolutionizing our approach to vaccine development, immunotherapy, and treatment of inflammatory disorders.

The immune system is not a homogeneous entity but a complex network of specialized cells distributed across distinct tissue niches throughout the body. Traditional immunology, heavily reliant on peripheral blood studies, has given way to a more nuanced understanding that immune cell function, maintenance, and response are profoundly shaped by their specific tissue microenvironment [2]. This paradigm shift has been accelerated by the detailed analysis of human tissues, with postmortem studies providing an unparalleled window into the spatial architecture of immunity in health and disease. Such research has definitively shown that immune responses are not uniform but are instead tailored to the unique challenges and functional requirements of each organ [9].

The concept of the immune niche refers to anatomically defined compartments that support the residence and function of immune cells, facilitating interactions with structural cells, cytokines, and signaling molecules that collectively orchestrate local immunity [10]. Understanding these niches—including the lung, lymphoid organs like the spleen and lymph nodes, and barrier surfaces such as the gut—is critical for deciphering the pathogenesis of infectious, inflammatory, and autoimmune diseases. This guide synthesizes findings from recent human postmortem studies to provide a technical overview of the key immune niches, detailing their cellular composition, functional specializations, and the experimental approaches used to profile them.

Profiling Key Immune Niches in Human Tissues

Advanced single-cell technologies have enabled high-resolution mapping of the immune landscape across the human body. The table below summarizes quantitative findings on immune cell distribution and age-related changes from a comprehensive multimodal study profiling over 1.25 million cells from multiple donors [2].

Table 1: Immune Cell Composition and Age-Associated Changes Across Key Tissue Niches

| Tissue Niche | Dominant Immune Cell Subsets | Key Tissue-Resident Features | Noted Age-Associated Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung & Airways | - CD8+ and CD4+ Tissue-Resident Memory T (TRM) cells- Mature CD56dimCD16+ NK cells- Alveolar Macrophages | - TRM cells expressing CD69, CD103, and/or CD49a- Strategic positioning for rapid response [9] | - Functional and metabolic changes in macrophages- Alterations in CD8+ T cell function |

| Lymph Nodes (Various) | - CD4+ Naive T (TN) cells- CD4+ Central Memory T (TCM) cells- Germinal Center B cells- Regulatory T (Treg) cells | - Enriched Treg population- CD69+ memory B cells denoting tissue residency | - Significant changes in B cell composition |

| Spleen | - CD8+ Terminal Effector (TEMRA) cells- Mucosal-Associated Invariant T (MAIT) cells- CD11c+ T-bet+ "Atypical" B cells | - Enriched TEMRA and MAIT cells | - Changes in B cell composition |

| Mucosal Barrier (Jejunum) | - CD4+ and CD8+ TRM cells- CD16‑NCR2+IL7R‑ ILC1s- IgA+ Plasma Cells | - Highest frequency of TRM cells- ILC1s with high CD69, CD49a, CD103 expression | - Changes in macrophage signatures |

Deep Dive into Niche-Specific Architecture and Function

Lung: A Frontline Defense Nexus

The lung's immune architecture is organized to respond to a constant barrage of inhaled antigens while maintaining gas exchange. Its homeostasis is maintained by a coordinated effort between alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) and macrophages [11]. AEC II cells are immunologically active, producing cytokines and chemokines, and can act as antigen-presenting cells [11].

The innate defense is coordinated by a network of cells including alveolar macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and recruited neutrophils. A key adaptive player is the tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cell population. Recent research reveals that lung TRM cells are not uniform; their function is dictated by their precise location within the lung's architecture [9]. These cells are strategically positioned to provide a swift, localized response to reinfection, orchestrating a broader immune response while minimizing damaging inflammation [9]. In severe pulmonary infections like COVID-19, postmortem studies have identified a hallmark of myeloid activation coupled with lymphocyte suppression. Activated myeloid cells (CD80/83+ CD206+ macrophages and BDCA2+/BATF3+ DCs) are found proximal to viral antigens, while lymphocytes, particularly CD8+ T cells and NK cells, are suppressed and distally located [12].

Lymph Nodes and Spleen: Hubs of Adaptive Immunity

As secondary lymphoid organs, the lymph nodes (LNs) and spleen are specialized for initiating adaptive immune responses and maintaining immune memory.

- Lymph Nodes: LNs are critical sites for antigen presentation and lymphocyte activation. Multimodal profiling shows LNs are enriched for naive T cells (TN), central memory T cells (TCM), and germinal center B cells, which are essential for generating high-affinity antibodies [2]. A key feature is the significant enrichment of regulatory T cells (Treg), highlighting the role of LNs in maintaining immune tolerance [2]. Furthermore, the presence of CD69-expressing memory B cells indicates a population of tissue-resident B cells that contribute to long-term local immunity [2].

- Spleen: The spleen acts as a blood filter and is a major site for immune responses against blood-borne pathogens. It is characterized by an abundance of terminally differentiated CD8+ TEMRA cells and Mucosal-Associated Invariant T (MAIT) cells [2]. The spleen also harbors a unique subset of CD11c+ T-bet+ "atypical" B cells, which are associated with chronic inflammatory conditions and age-related immune changes [2].

Barrier Surfaces: The Gut as a Model

Barrier surfaces like the gut interface directly with the external environment. The jejunum, for instance, demonstrates a profoundly tissue-tailored immune system. It contains the highest frequency of CD4+ and CD8+ TRM cells across all tissues studied, identified by their expression of residency markers CD69, CD103, and CD49a [2]. The gut niche also supports specialized innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), particularly NCR2+IL7R− ILC1s, which also exhibit a strong tissue-resident signature [2]. Finally, the lamina propria is enriched with IgA+ plasma cells, underscoring the niche's focus on producing mucosal antibodies that neutralize pathogens without provoking excessive inflammation [2].

Table 2: Key Surface Markers for Identifying Tissue-Resident Immune Cells

| Cell Type | Core Defining Markers | Function & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| TRM (General) | CD69, CD103 (αE integrin), CD49a | Non-recirculating, sentinel function in tissues; rapid local response [13]. |

| Circulating Memory T Cells | CCR7, CD62L (L-selectrin) | Recirculate between blood and secondary lymphoid organs [13]. |

| CD8+ TEMRA | CD45RA, KLRG1 | Terminally differentiated effector cells; enriched in spleen and blood [2]. |

| CD4+ Treg | FOXP3, CD25 | Immunosuppressive function; enriched in lymph nodes [2] [10]. |

| Atypical B Cell | CD11c, T-bet (TBX21) | Associated with chronic infection and age; enriched in spleen [2]. |

Methodologies for Mapping Tissue Niches in Postmortem Studies

The insights gleaned from tissue niches rely on sophisticated experimental protocols. The following workflow and toolkit detail the key approaches.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for tissue immune profiling.

Core Experimental Protocols

1. Tissue Acquisition and Single-Cell Suspension Preparation:

- Source: Tissues (blood, lymphoid organs, lungs, intestines) are obtained from organ donors or postmortem patients [2] [14].

- Processing: Tissues are dissociated using established mechanical and enzymatic protocols to create viable single-cell suspensions while preserving cell surface epitopes [2].

- Critical Consideration: Rapid processing is essential to maintain RNA integrity and protein expression for downstream assays.

2. Multimodal Single-Cell Profiling (CITE-seq):

- Principle: Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing (CITE-seq) simultaneously measures single-cell transcriptomes and over 100 surface proteins using antibody-derived tags (ADTs) [2].

- Procedure: Cells are stained with a panel of DNA-barcoded antibodies. Single cells are then encapsulated into droplets with barcoded beads for RNA and ADT capture, followed by library preparation and next-generation sequencing [2].

- Advantage: Resolves cell states that are indistinguishable by transcriptomics alone (e.g., distinguishing naive from central memory T cells via CD45RA) [2].

3. Spatial Validation using Multiplex Immunohistochemistry (mIHC) and Digital Spatial Profiling (DSP):

- Principle: Confirms the spatial relationships and protein expression identified in single-cell data within the intact tissue architecture.

- mIHC Protocol: Sequential staining of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections with antibodies conjugated to fluorescent dyes or metal tags, followed by high-resolution imaging [12] [15].

- DSP Protocol: FFPE sections are stained with oligonucleotide-barcoded antibodies. Regions of interest are selected and irradiated with UV light to release barcodes for quantification, allowing correlation of protein expression with tissue morphology [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Tissue Niche Profiling

| Reagent / Technology | Function in Experimental Pipeline |

|---|---|

| Panels of DNA-Barcoded Antibodies (CITE-seq) | Enable simultaneous quantification of >100 cell surface proteins alongside transcriptome in single cells [2]. |

| Multiplex Immunohistochemistry/Optical Clearing Kits | Allow visualization of multiple protein targets on a single tissue section, preserving spatial context [12] [15]. |

| Hash Tag Oligonucleotides (HTOs) | Enable sample multiplexing by labeling cells from different donors/tissues with unique barcodes, reducing batch effects and costs [14]. |

| Bioinformatic Tools (MrVI, MMoCHi, Seurat) | MrVI: Integrates data across samples and models technical variation [2]. MMoCHi: Uses protein and RNA data for automated cell classification [2]. Seurat: Standard toolkit for single-cell data analysis [14]. |

| AL-438 | AL-438, CAS:239066-73-0, MF:C23H25NO2, MW:347.4 g/mol |

| Boc-NH-PEG12-NH-Boc | Boc-NH-PEG12-NH-Boc, MF:C36H72N2O16, MW:789.0 g/mol |

The shift from a blood-centric to a tissue-centric view of immunology, powered by postmortem studies and advanced technologies, has revealed that immune protection is a local phenomenon orchestrated by specialized niches. The lung, lymph nodes, spleen, and barrier surfaces each maintain a unique ecosystem of resident immune cells whose function is dictated by their tissue microenvironment. This refined understanding is paving the way for a new generation of niche-specific therapeutic strategies, such as vaccines designed to induce protective TRM cells in barrier tissues or immunotherapies that target exhausted T cells within the tumor microenvironment. Future research will continue to decode the molecular signals that establish and maintain these niches, offering unprecedented opportunities for precise manipulation of immunity in human health and disease.

The immune system is a dynamic network of specialized cells distributed throughout the body to defend against infections, regulate inflammation, and repair tissue damage. Rather than functioning as a homogeneous system, immune cells exhibit remarkable functional specialization based on their tissue location. Understanding how the tissue microenvironment shapes immune cell identity, composition, and function represents a critical frontier in immunology with profound implications for therapeutic development. This technical guide examines the mechanisms of functional adaptation, drawing on evidence from human postmortem studies that provide unprecedented access to tissue-resident immune populations across the human body.

Tissue-Specific Immune Cell Profiling

Comprehensive Mapping of Immune Landscapes

Groundbreaking research utilizing single-cell multimodal profiling has revolutionized our understanding of tissue-specific immunity. A landmark 2025 study published in Nature Immunology comprehensively profiled over 1.25 million immune cells from blood, lymphoid, and mucosal tissues from 24 organ donors aged 20-75 years [2]. Using cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes (CITE-seq) to simultaneously profile transcriptomes and >125 surface proteins, researchers identified dominant site-specific effects on immune cell composition and function across lineages [2].

Table 1: Tissue-Specific Enrichment of Immune Cell Subsets

| Immune Cell Subset | Enriched Tissue Sites | Key Identifying Markers | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ and CD8+ Tissue-Resident Memory T (TRM) cells | Jejunum (JEL, JLP), Lungs, Spleen, LN | CD69, CD103, CD49a [2] | Long-term tissue surveillance, rapid response to local pathogens |

| CD4+ Naive T (TN) cells | Blood, Multiple Lymph Nodes | CD45RA+ [2] | Antigen-naive precursors to effector/memory populations |

| CD8+ TEMRA cells | Bone Marrow, Spleen | CD45RA+, KLRF1, GZMB [2] | Terminally differentiated effectors with cytotoxic capability |

| CD56dimCD16+ NK cells | Blood, Bone Marrow, Lungs | KLRF1, GZMB [2] | Mature cytotoxic function |

| CD11c+ Memory B cells | Spleen, Bone Marrow | TBX21 (T-BET) [2] | "Atypical" B cell subset with specialized effector functions |

| IgA+ Plasma Cells | Jejunum Lamina Propria (JLP) | SDC1 (CD138) [2] | Mucosal antibody production |

| ILC1 | Jejunum | CD16-NCR2+IL7R-, CD69, CD49a, CD103 [2] | Tissue-resident innate immunity |

The distribution of T cell subsets varies dramatically across tissue sites. CD4+ naive T (TN) and central memory T (TCM) cells are predominantly enriched in blood and lymph nodes, while CD4+ and CD8+ tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells prevail in jejunum and are present at lower frequencies in lungs, spleen, and lymph nodes [2]. CD8+ TEMRA cells, which exhibit terminally differentiated effector phenotypes, are primarily found in bone marrow and spleen [2].

Innate lymphoid populations also demonstrate tissue-specific patterning. Mature CD56dimCD16+ natural killer (NK) cells expressing cytolytic markers (KLRF1, GZMB) are enriched in blood, bone marrow, and lungs, while CD16-NCR2+IL7R- innate lymphoid cell 1 (ILC1) subsets with high expression of tissue residency markers (CD69, CD49a, CD103) are predominantly localized to jejunum [2].

B cell subset distribution is largely restricted to lymphoid organs, with notable tissue-specific specialization. CD11c+ memory B cells expressing TBX21 (encoding T-BET) resemble "atypical B cells" and localize primarily to spleen and bone marrow, while IgA+ plasma cells are uniquely enriched in jejunal lamina propria [2].

Table 2: Age-Associated Changes in Tissue-Specific Immune Populations

| Tissue Site | Immune Population | Age-Associated Changes |

|---|---|---|

| Mucosal Sites | Macrophages | Functional and compositional alterations [2] |

| Lymphoid Organs | B Cells | Compositional and functional shifts [2] |

| Blood & Tissues | CD8+ T cells | Functional, signaling, and metabolic changes [2] |

| Circulating Compartment | T cells and NK cells | Functional alterations across blood and tissues [2] |

Impact of Aging on Tissue-Specific Immunity

Aging exerts distinct effects on immune populations that vary by tissue site and lineage. While tissue-specific immune cell composition is largely maintained with age, significant functional, signaling, and metabolic alterations occur in specific subsets and locations [2]. Macrophages in mucosal sites, B cells in lymphoid organs, and circulating T cells and natural killer (NK) cells across blood and tissues demonstrate particular susceptibility to age-associated changes [2]. This age-related immunological decline, termed immunosenescence, involves progressive deterioration of both innate and adaptive immunity, though not all components are affected equally [16].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Tissue Immunity

Postmortem Tissue Processing and Cell Isolation

The study of human tissue immunity requires specialized methodologies for tissue acquisition and cell isolation. Postmortem tissues obtained from organ donors with appropriate ethical approvals and informed consent provide invaluable access to multiple tissue sites from individual donors [2] [17].

Diagram 1: Tissue Processing Workflow

For solid tissues such as lung, enzymatic digestion combined with mechanical dissociation is employed. The process involves cutting tissue into small pieces followed by incubation with an enzyme mixture typically containing collagenase D (1 mg/ml) and DNase I (1 μg/ml) [18]. Physical disintegration using instruments such as the gentleMACS Octo Dissociator with specific programs (e.g., "Lung Program 1" and "Lung Program 2") enhances cell yield [18]. The resulting suspension is sequentially filtered through 70μm and 40μm filters to remove debris and obtain a single-cell suspension [18].

Immunopanning provides an alternative approach for prospective purification of specific glial cells from human postmortem brain tissue [17]. This method uses cell type-specific antibodies coated on petri dishes to selectively isolate microglia, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes from cortical gray matter [17].

Multimodal Single-Cell Profiling

Cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes (CITE-seq) enables simultaneous profiling of transcriptomes and surface proteins at single-cell resolution [2]. This methodology allows for comprehensive immune cell annotation using tools such as MultiModal Classifier Hierarchy (MMoCHi), which leverages both surface protein and gene expression to hierarchically classify cells into predefined categories [2].

Diagram 2: Multimodal Profiling Pipeline

For data integration, multi-resolution variational inference (MrVI) is particularly valuable for cohort studies as it harmonizes variation between cell states while accounting for differences between samples [2]. Visualization with uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) enables comparison across donors, sequencing technologies, and donor covariates such as sex and viral serostatus [2].

Ex Vivo Tissue Models

Advanced ex vivo models have been developed to study human immune responses in preserved tissue contexts. A hydrogel-based lymph node slice platform enables extended culture of patient-derived LN tissues, maintaining architecture, viability, and immune responsiveness for at least 7 days [19]. This system reduces cell egress and preserves LN cellular composition, phenotype, and spatial architecture, allowing evaluation of antitumoral and vaccine responses [19].

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Impact of Postmortem Interval

The postmortem interval (PMI) - the time between death and tissue preservation - represents a critical variable in postmortem tissue studies. Research indicates that even a 3-hour PMI can diminish detection of disease-specific transcriptomic signatures in brain tissues [20]. Basic quality control metrics such as the number of genes and reads per cell, total nuclei counts, and RNA integrity number may remain consistent, but differential gene expression between experimental conditions can be obscured [20].

PMI induces distinct transcriptional changes across cell types. In neurons, upregulated genes are involved in DNA repair, immune response, and stress pathways, while non-neuronal cell types show alterations in genes associated with cell-cell adhesion processes [20]. These effects highlight the importance of standardized PMI documentation and consideration in experimental design.

Methodological Constraints

Tissue-specific immune studies face several methodological challenges:

- Cell viability: Rapid processing is essential to maintain cell viability and preserve native transcriptional states [17].

- Representation of rare populations: Low-abundance immune subsets may be underrepresented in standard processing workflows.

- Spatial context loss: Single-cell dissociation methods disrupt native tissue architecture and cell-cell interactions.

- Technical variability: Differences in tissue collection, processing, and analysis protocols can introduce batch effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Tissue Immune Studies

| Reagent/Equipment | Application | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagenase D + DNase I | Tissue dissociation | Enzymatic digestion of extracellular matrix | 1 mg/ml Collagenase D, 1 μg/ml DNase I [18] |

| gentleMACS Octo Dissociator | Tissue dissociation | Mechanical disintegration of solid tissues | Programmed protocols (e.g., "Lung Program 1") [18] |

| Anti-CD11b, Anti-O4, Anti-HepaCAM | Immunopanning | Isolation of microglia, oligodendrocytes, astrocytes | Coated on polystyrene Petri dishes [17] |

| CITE-seq Antibody Panels | Multimodal profiling | Simultaneous protein and transcript detection | >125 surface protein targets [2] |

| HA Hydrogels | Ex vivo culture | Preservation of tissue architecture in LN slices | Support viability for ≥7 days [19] |

| 10X Genomics Chromium | Single-cell sequencing | Single-cell partitioning and barcoding | 3' Gene Expression Kit v3.1 [20] |

| Pybg-tmr | Pybg-tmr, MF:C40H35N7O5, MW:693.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Fmoc-Cys-Asp10 | Fmoc-Cys-Asp10, MF:C58H67N11O34S, MW:1494.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Immune cells demonstrate remarkable functional adaptation to their tissue microenvironments, exhibiting distinct compositional, phenotypic, and transcriptional profiles across different organs. The integration of advanced methodologies including multimodal single-cell profiling, sophisticated computational integration, and ex vivo tissue models provides unprecedented insight into these tissue-specific immune signatures. While technical challenges remain, particularly regarding postmortem interval effects and methodological standardization, ongoing technological innovations continue to enhance our understanding of how tissue microenvironments shape immune identity and function. This knowledge provides critical foundations for developing targeted therapeutic interventions that account for tissue-specific immune responses.

The immune system represents a clear example of an evolutionary arms race, constantly adapting under pressure from pathogens to maintain effective host defense. While the role of protein-coding genes in this process has been studied, a critical gap exists in understanding how adaptation manifests within the specific cellular contexts of human barrier tissues—the primary interfaces facing external pathogens. Recent advances in single-cell technologies and the development of comprehensive tissue atlases now enable the investigation of immune adaptation at unprecedented cellular resolution. This whitepaper synthesizes evidence from human postmortem studies to elucidate the distinct evolutionary pressures shaping immune cells in barrier tissues, providing a framework for understanding tissue-specific adaptation and its implications for therapeutic development.

Evidence of Adaptation in Barrier Tissue Immune Cells

Cellular Resolution of Immune Adaptation

Table 1: Key Evidence of Immune Cell Adaptation in Barrier Tissues

| Evidence Type | Key Finding | Experimental Approach | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular adaptation rate | Tissue-resident T and NK cells in adult lung show significantly increased adaptation rates | ABC-MK test on Human Cell Atlas data | [21] |

| Spatial distribution | Immune cells at tissue compartments directly facing external challenges show highest adaptation | Spatial transcriptomics from Lung Cell Atlas | [21] |

| Temporal patterns | Progenitor cells during development and adult cells in barrier tissues harbor increased adaptation | Developmental and Adult Immune Cell Atlas analysis | [21] |

| Functional specialization | Tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) show distinct adaptation signatures | Single-cell RNA sequencing with differential gene expression | [21] [2] |

| Aging effects | Tissue residence may protect against immunosenescence in mucosal sites | Radiocarbon dating and turnover measurements | [22] |

Analysis of data from the Human Cell Atlas reveals abundant cell types, including progenitor cells during development and adult cells in barrier tissues, harbor significantly increased adaptation rates [21]. Research confirms the particular adaptation of tissue-resident T and NK cells in the adult lung located in compartments directly facing external challenges, such as respiratory pathogens [21]. This spatial organization of adaptation highlights how evolutionary pressures have shaped immune cells based on their functional positioning within tissue architectures.

Methodological Framework for Detecting Adaptation

The detection of adaptation in immune cells relies on sophisticated population genetics approaches applied to transcriptomic data. The primary method involves:

ABC-MK Test Implementation:

- Data Input: Top 500 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) per cell population (FDR < 1×10-4, logFC > 1)

- Statistical Framework: Approximate Bayesian Computation extension of McDonald-Kreitman test

- Adaptation Metrics: Proportion of adaptive non-synonymous substitution (α) and rate of adaptive non-synonymous substitution (ωa)

- Null Distribution: 1000 control datasets matching immune gene subset size [21]

This approach accounts for weakly selected polymorphisms and background selection, which can bias traditional tests of positive selection. By modeling multiple distributions of fitness effects alongside background selection, ABC-MK provides more accurate inference of adaptation parameters in heterogeneous genomic datasets [21].

Figure 1: Workflow for detecting immune cell adaptation in barrier tissues using single-cell data and population genetics approaches.

Tissue-Specific Immune Responses and Adaptation

Barrier Tissue Immune Niches

Human barrier tissues maintain distinct immune niches with specialized functional adaptations. Multimodal profiling of over 1.25 million immune cells from blood, lymphoid, and mucosal tissues reveals dominant site-specific effects on immune cell composition and function across lineages [2]. The tissue environment exerts a powerful influence on immune cell phenotypes, with mucosal sites such as the gut and lungs exhibiting unique immune signatures distinct from lymphoid organs or circulation.

Table 2: Tissue-Specific Immune Cell Distribution and Adaptation

| Tissue Site | Dominant Immune Cell Types | Key Adapted Functions | Age-Related Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung parenchyma & BAL | CD8+ TRM (CD69+CD103+), CD56dimCD16+ NK cells | Pathogen recognition, early response to respiratory pathogens | Macrophage functional alterations [2] |

| Jejunum (intestinal epithelium) | CD4+ and CD8+ TRM, CD16−NCR2+IL7R− ILC1s | Mucosal surveillance, barrier maintenance | Stable TRM maintenance with age [22] |

| Mesenteric lymph nodes | CD4+ Treg cells, germinal center B cells, ILC3s | Immune regulation, tolerance induction | B cell composition changes [2] |

| Skin | Tissue Tregs, resident macrophages | Wound healing, tissue repair | Not comprehensively studied [23] |

Tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells demonstrate particularly strong signatures of adaptation. These cells are strategically positioned at barrier sites and exhibit enhanced functionality against previously encountered pathogens. In the lungs, TRM cells located at mucosal surfaces directly interfacing with the environment show the highest adaptation rates, reflecting their position at the frontline of host defense [21].

Structural Immunity and Barrier Reinforcement

The concept of "structural immunity" has emerged as an important adaptation in barrier tissues. This paradigm posits that the first line of immune defense involves the physical reinforcement of tissue barriers, a task directly or indirectly regulated by immune cells [24]. Several leukocyte subtypes help build protective barriers, either by depositing matrix components themselves or through interactions with structural cells and the extracellular matrix.

This structural function challenges traditional compartmentalization of mammalian tissue organization and immune defense. Immune cells acting as architects of tissue barriers represent an evolutionary adaptation that physically prevents pathogen entry, complementing traditional immunological recognition and elimination mechanisms [24].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Human Tissue Processing and Cell Isolation

Tissue Acquisition and Processing Protocol:

- Source: Multiorgan donors (ages 2-93) through organ procurement organizations

- Tissues: Blood, lung, jejunum, spleen, lung-associated and mesenteric lymph nodes

- Processing: Mechanical dissociation followed by enzymatic digestion with Liberase TM (0.25 mg/ml)

- Cell Isolation: Density gradient centrifugation for mononuclear cell separation [22] [2]

Critical Considerations:

- Postmortem intervals minimized to maintain cell viability

- Exclusion criteria: chronic infection, cancer, overt inflammatory disease

- Demographic matching for age and sex comparisons [22] [2]

Single-Cell Multimodal Profiling

Advanced single-cell technologies enable comprehensive immune characterization:

CITE-seq (Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes) Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: 1.28 million immune cells from 10+ tissue sites

- Antibody Panel: 127 surface protein markers

- Sequencing: Single-cell RNA sequencing with feature barcoding

- Data Integration: Multi-resolution variational inference (MrVI) for harmonization

- Cell Annotation: MultiModal Classifier Hierarchy (MMoCHi) leveraging both surface protein and gene expression [2]

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for multimodal profiling of human tissue immune cells from acquisition to adaptation analysis.

Lineage Tracing and Cellular Aging Studies

Retrospective Birth Dating of Human T Cells:

- Methodology: Radiocarbon (14C) dating based on atmospheric nuclear bomb testing

- Measurement: Determination of genomic DNA incorporation timing

- Lifespan Calculations: Integration with cellular turnover measurements [22]

Key Findings on T Cell Longevity:

- Blood and lymph node T cells: 1-2 years lifespan

- Splenic T cells: 3-10 years lifespan

- Tissue-resident memory T cells exhibit distinct aging dynamics with reduced senescent markers compared to circulating counterparts [22]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liberase TM | Tissue dissociation | Enzymatic digestion of extracellular matrix | 0.25 mg/ml for 30-60 min at 37°C [25] [2] |

| CITE-seq antibody panels | Multimodal profiling | Simultaneous protein and RNA measurement | 127-surface protein panel [2] |

| Human Cell Atlas data | Reference mapping | Comprehensive transcriptome reference | Developmental and Adult Immune Cell Atlases [21] |

| ABC-MK algorithm | Adaptation rate calculation | Quantifying positive selection | Inference of α and ωa parameters [21] |

| MrVI (Multi-resolution Variational Inference) | Data integration | Harmonizing single-cell data across samples | Integration of datasets from multiple donors [2] |

| MMoCHi (MultiModal Classifier Hierarchy) | Cell annotation | Automated cell type classification | Leveraging protein and RNA for subset identification [2] |

| Fosfenopril-d7 | Fosfenopril-d7 | Fosfenopril-d7 is a deuterated internal standard for accurate LC/MS or GC/MS quantification of Fosinopril. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| hCAXII-IN-1 | hCAXII-IN-1|CA XII Inhibitor|For Research Use | hCAXII-IN-1 is a selective hCAXII inhibitor for cancer research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

Discussion and Therapeutic Implications

The evidence of accelerated adaptation in barrier tissue immune cells underscores the evolutionary prioritization of defense at host-environment interfaces. These findings have significant implications for vaccine development, immunotherapies, and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Therapeutic strategies targeting tissue-resident immune populations may enhance protection against pathogens while avoiding systemic immune activation.

Future research directions should include:

- Comprehensive mapping of adaptation across more tissue sites and immune subsets

- Investigation of how adaptive signatures correlate with response to infection, vaccination, and immunotherapy

- Development of tissue-targeted delivery systems that leverage adapted immune mechanisms

- Exploration of how modern environmental changes affect ongoing adaptation in barrier immunity

The integration of evolutionary genetics with tissue immunology provides a powerful framework for understanding the design principles of human immune defense and for developing next-generation therapeutic approaches that work in harmony with evolved tissue-specific immunity.

The human immune system is a complex, dynamic network distributed throughout the body, with specialized functions tailored to specific tissue environments. For decades, immunological monitoring has predominantly relied on peripheral blood samples due to their accessibility, creating a fundamental gap in our understanding of localized immune responses. While blood provides a convenient window into systemic immunity, it fails to capture the specialized immune populations, functional states, and cellular interactions within tissues where diseases actually occur. This limitation is particularly critical in the context of infectious diseases, cancer immunotherapy, and autoimmune disorders, where tissue-specific immune dynamics determine clinical outcomes.

Recent advances in high-dimensional spatial profiling and multimodal single-cell analysis of postmortem tissues have revolutionized our capacity to investigate tissue-specific immunity, revealing profound functional specializations that are undetectable in circulation. This technical guide synthesizes cutting-edge methodologies and findings from human postmortem studies to demonstrate why comprehensive immune profiling must extend beyond blood to understand physiological and pathological immune responses truly.

Compelling Evidence: Tissue-Specific Immunity Revealed Through Postmortem Studies

Distinct Immune Compartmentalization in Severe COVID-19

Postmortem immune profiling of COVID-19 decedents has provided unprecedented insights into the spatial organization of immune responses during severe infection. A comprehensive high-dimensional analysis of 22 COVID-19 decedents from Wuhan, China, revealed TIM-3-mediated and PD-1-mediated immunosuppression as a hallmark of severe disease, particularly in male patients [26]. This exhaustive study, which employed digital spatial profiling (DSP) and multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC) across multiple organs, discovered that lymphocytes were systematically distal from SARS-CoV-2 viral antigens, while activated myeloid cells were consistently proximal, indicating prevalent infection of myeloid cells across multiple organs [26].

Crucially, the study demonstrated significant sexual dimorphism in immune responses, with male patients showing higher expression of inhibitory receptors (TIM-3, PD-1, CD39, BTLA) and lower expression of immune activation markers (Ki-67, CD69) in lung tissue [26]. This tissue-specific immunosuppressive signature was more pronounced in men and correlated with shorter survival duration, highlighting a pathological mechanism that would be impossible to decipher from peripheral blood studies alone [26].

Table 1: Key Tissue-Specific Immune Findings in Severe COVID-19 from Postmortem Studies

| Finding | Experimental Method | Tissue Localization | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myeloid cell infection | Multiplex IHC, Spatial profiling | Lung, Liver, Kidney, Spleen | Myeloid cells proximal to viral antigen; lymphocytes distal |

| Sex-specific immunosuppression | Bulk RNA-seq, mIHC | Lung, Kidney, Heart | TIM-3/PD-1 upregulation in males across organs |

| Viral load correlation | DSP, RNA-seq | Multiple organs | Positive correlation with immunosuppression and DC markers |

| Organ-specific NK cell activity | Spatial cell profiling | Lung vs. Liver | NK cells proximal to virus in liver but distal in lung |

Age and Tissue Microenvironment Interactions

A landmark 2025 study profiling over 1.25 million immune cells from blood, lymphoid, and mucosal tissues from 24 organ donors aged 20-75 years provided comprehensive evidence of tissue-directed immune signatures that vary with age [2]. Using cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes (CITE-seq) to simultaneously profile transcriptomes and >125 surface proteins, researchers demonstrated that immune cell composition and function are predominantly determined by tissue site rather than circulation [2].

The study revealed that age-associated effects manifest specifically by tissue site and lineage: macrophages in mucosal sites, B cells in lymphoid organs, and circulating T cells and natural killer cells across blood and tissues showed distinct aging patterns [2]. For instance, memory B cells in lymphoid organs expressed CD69, denoting tissue residency, while plasma cells expressing IgA were enriched in the jejunal lamina propria, and IgG+ plasmablasts were enriched in lymphoid organs [2]. These findings establish that aging exerts highly specific effects on immune populations depending on their tissue localization, information completely masked in blood-only analyses.

Table 2: Tissue-Specific Immune Cell Distributions Revealed by Multimodal Profiling

| Immune Cell Type | Tissue-Specific Enrichment | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| CD4+/CD8+ TRM cells | Jejunum, Lungs, Spleen, LN | Tissue-resident memory positioned for rapid local response |

| CD8+ TEMRA cells | Bone Marrow, Spleen | Terminally differentiated effectors in lymphoid reservoirs |

| MAIT cells | Spleen, BM, Lungs | Mucosal-associated invariant T cells at barrier sites |

| IgA+ Plasma cells | Jejunal Lamina Propria | Specialized for mucosal antibody production |

| CD56dimCD16+ NK cells | Blood, BM, Lungs | Cytolytic effectors at infection sites |

| CD11c+ Memory B cells | Spleen, BM | T-bet+ "atypical" B cells in lymphoid organs |

Methodological Framework: Postmortem Tissue Immune Profiling

Technical Considerations for Postmortem Studies

Postmortem tissue studies present unique methodological challenges that must be addressed to ensure data quality and interpretability. Confounding factors including sex, age at death, medication history, agonal state, postmortem interval (PMI), tissue storage duration, tissue pH, and RNA integrity number (RIN) significantly impact gene expression profiles [27]. A 2025 systematic assessment demonstrated that pH and RIN values particularly affect genes involved in energy production, immune system function, and DNA repair pathways [27].

The postmortem interval critically influences molecular integrity, with studies showing progressive RNA degradation over time. Research in rat models demonstrates that brain tissue morphology remains stable at 4°C for up to 21 days, while at 26°C, cytoplasmic and cell destruction becomes evident after 14 days [28]. Among housekeeping genes, Gapdh and 5S rRNA show high stability across extended PMIs, making them suitable reference genes for molecular analyses [28].

Advanced Spatial Profiling and Tissue Clearing Techniques

The development of SHARD (SHIELD, antigen retrieval, and delipidation) has dramatically improved capacity for three-dimensional immunostaining in long-term formaldehyde-fixed postmortem human brain tissue [29]. This method combines tissue stabilization, antigen retrieval, and lipid removal to enable high-resolution visualization of cellular morphology and spatial relationships in tissues with PMIs ranging from 10 to 72 hours [29].

For multiplexed protein detection, mass cytometry-based systems like the Maxpar Direct Immune Profiling System enable simultaneous measurement of 37+ immune cell types using metal-tagged antibodies, providing exceptional stability for multicenter studies [30]. When combined with spatial techniques like digital spatial profiling, researchers can achieve comprehensive molecular and spatial characterization of immune responses directly in tissues [26].

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Workflow for Postmortem Tissue Immune Profiling

Integrated Framework for Tissue Analysis

An effective organ-specific immunity research framework incorporates multiple complementary approaches. A 2023 study established a tissue analysis framework that combines digital pathology with molecular profiling to investigate local immune responses, emphasizing the importance of studying mucosal lymphoid tissues, macrophages, and dendritic cells in their native tissue context [31]. This integrated approach enables researchers to correlate specific immune cell populations with tissue injury patterns and pathogen localization, providing mechanistic insights into disease pathogenesis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Tissue-Based Immune Profiling

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application in Postmortem Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Maxpar Direct Immune Profiling Assay | High-parameter metal-tagged antibody panel | Standardized immunophenotyping of 37+ immune cell types in tissue digests |

| CITE-seq | Simultaneous transcriptome and surface protein profiling | Multimodal single-cell analysis of immune cell identity and function |

| SHARD Clearing Method | Tissue clarification and antigen retrieval | 3D immunostaining in long-term formaldehyde-fixed tissue |

| Digital Spatial Profiling | Spatially-resolved whole transcriptome analysis | Mapping immune cell localization relative to pathogens or pathology |

| Multiplex IHC | Simultaneous detection of multiple protein markers | Spatial characterization of immune cell populations and states |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preservation of RNA integrity | Maintain molecular quality despite postmortem delays |

| IHCH-3064 | IHCH-3064, MF:C25H21N9O2, MW:479.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| H-Lys(Z)-OH-d3 | H-Lys(Z)-OH-d3, MF:C14H20N2O4, MW:283.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

SHARD Protocol for Tissue Clearing and Staining

The SHARD method enables robust three-dimensional imaging in challenging postmortem human brain tissue. The optimized protocol includes [29]:

- Tissue Stabilization: Incubate 200-μm tissue sections in SHIELD Epoxy Solution (LifeCanvas Technologies) for 48 hours at 4°C to stabilize macromolecules.

- Antigen Retrieval: Perform citrate-based antigen retrieval by incubating tissue in sodium citrate buffer (pH 9.0) at 80°C for 30 minutes to reverse formaldehyde cross-linking.

- Lipid Removal: Treat tissue with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for 24-48 hours with gentle agitation to remove lipids and achieve optical clarity.

- Immunostaining: Incubate cleared tissue with primary antibodies for 48-72 hours, followed by fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies for 24-48 hours.

- Refractive Index Matching: Mount tissue in SHIELD Mounting Medium (LifeCanvas Technologies) for 24 hours before imaging.

This method successfully processes tissues with PMIs ranging from 10-72 hours across various neurodegenerative conditions and controls, making it particularly suitable for human brain bank samples [29].

High-Dimensional Immune Profiling Workflow

A comprehensive tissue-based immune profiling workflow incorporates both single-cell and spatial techniques [26] [2]:

- Tissue Digestion: Mechanically dissociate and enzymatically digest fresh tissue using collagenase/DNase cocktail to generate single-cell suspensions while preserving surface epitopes.

- Multimodal Single-Cell Profiling:

- Stain cells with CITE-seq antibody panels (127+ surface markers) with barcoded oligonucleotides

- Partition single cells using droplet-based microfluidics (10X Genomics)

- Prepare sequencing libraries for both transcriptome and surface protein detection

- Spatial Transcriptomics:

- Process adjacent tissue sections for spatial transcriptomics using Visium platform (10X Genomics)

- Correlate single-cell data with spatial localization patterns

- Multiplex Immunohistochemistry:

- Stain consecutive sections with validated antibody panels for immune activation (CD69, IFN-γ, granzyme B) and suppression markers (TIM-3, PD-1, BTLA)

- Quantify cell densities and spatial distributions using automated image analysis

Diagram 2: Tissue-Specific Immune Dysregulation Pathway in Severe COVID-19

The evidence from sophisticated postmortem tissue studies unequivocally demonstrates that peripheral blood provides an incomplete and often misleading representation of immune responses. Tissue-specific immune signatures, spatial organization of immune populations, and localized functional states critically determine pathological outcomes in infectious diseases, cancer, and inflammatory disorders. The integrated methodological framework presented here—combining multimodal single-cell analysis, spatial transcriptomics, and advanced tissue clearing techniques—enables comprehensive characterization of immune responses in their native tissue context.

For drug development professionals, these findings highlight the limitations of blood-based biomarkers and emphasize the necessity of developing tissue-targeted therapeutic strategies and localized immunomonitoring approaches. As immunology advances beyond its blood-centric legacy, embracing tissue-informed paradigms will be essential for developing next-generation immunotherapies and precision medicine approaches that account for the spatial dimension of immune responses.

Tools of the Trade: Profiling Immune Responses in Postmortem Tissues

Postmortem tissue samples are an indispensable resource for studying the molecular underpinnings of human health and disease, particularly for organs like the brain that cannot be sampled in living individuals. However, the validity of findings from these tissues hinges on recognizing and controlling for the profound effects of postmortem interval (PMI)—the time between death and tissue preservation—on molecular integrity. Research demonstrates that PMI is not merely a logistical variable but a biological process that actively alters the tissue's molecular landscape. A landmark study from Mount Sinai's Living Brain Project revealed "unequivocal evidence that brain tissue from living people has a distinct molecular character" compared to postmortem samples, with over 60% of proteins and 95% of RNA types showing differential expression or processing [32]. These findings necessitate a rigorous framework for tissue collection and processing that minimizes artifacts and preserves biological signals, especially when investigating delicate processes like tissue-specific immune responses.

This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for postmortem tissue collection and processing, with particular emphasis on maintaining the integrity of immune signatures. We synthesize recent evidence on PMI-induced molecular changes, present optimized protocols for tissue preservation and nuclei isolation, and provide quantitative data on molecular degradation timelines to inform experimental design in translational research and drug development.

Molecular Consequences of Postmortem Interval

Transcriptomic and Proteomic Alterations

The postmortem period triggers rapid and extensive molecular changes that can obscure disease-specific signatures if not properly accounted for. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing studies in mouse models demonstrate that even a 3-hour PMI significantly diminishes the detection of disease-associated transcriptomic signatures, particularly in neuronal populations [20]. Comparative proteomic analyses between human and mouse models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) further reveal that PMI affects the representation of key biological processes, with human postmortem tissues showing prominent upregulation of immune processes and downregulation of mitochondrial function—patterns not consistently recapitulated in immediately processed animal models [33].

Table 1: Quantitative Molecular Changes Following Postmortem Interval

| Molecular Component | Experimental System | PMI Duration | Key Changes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA splicing & processing | Human prefrontal cortex | Variable (living vs postmortem) | 95% of tested RNA transcripts showed differences in splicing, primary RNA levels, or mature RNA levels | [32] |

| Protein expression | Human prefrontal cortex | Variable (living vs postmortem) | >60% of proteins differentially expressed between living and postmortem tissue | [32] |

| Disease-specific gene expression | PS19 tauopathy mouse model | 3 hours | Diminished number of genes differentially expressed between disease and WT models | [20] |

| Mitochondrial transcripts | Rat skeletal muscle | 48 hours | Significant upregulation of mt-ATP6, mt-ATP8, and mt-CO3 (FC > 7.78) | [34] |

| Vascular & metabolic pathways | Rat skeletal muscle | 48 hours | Upregulated nitric oxide transport; downregulated mitochondrial activity | [34] |

Cell-Type-Specific Vulnerabilities

Different cell populations exhibit distinct vulnerabilities to postmortem degradation processes. Neuronal gene expression signatures appear particularly susceptible to PMI effects, with studies showing that "PMI can obscure disease-related gene expression changes, especially in neurons" [20]. In contrast, glial-specific gene expression may demonstrate greater resilience to postmortem degradation. Analysis of postmortem interval effects at single-nucleus resolution identified PMI-induced upregulation of genes involved in DNA repair, immune response, and stress pathways in neurons and interneurons, while alterations in non-neuronal cell types were associated with cell-cell adhesion processes [20].

Practical Protocols for Tissue Processing and Analysis

Optimized Nuclei Isolation from Postmortem Primate Brain Tissue

The isolation of high-quality nuclei from postmortem frozen tissue is a critical first step for single-cell sequencing and other genomic applications. The following protocol has been specifically optimized for challenging postmortem primate brain tissue and addresses common issues including high debris, reduced RNA integrity, and autofluorescence [35]:

Tissue Preparation: Microdissect frozen cerebral cortex tissue on dry ice using a 2mm biopsy punch, yielding 25-50mg tissue samples. Maintain tissue frozen throughout dissection to prevent thawing.

Nuclei Isolation: Use the 10X Genomics Chromium Nuclei Isolation Kit with RNase Inhibitor with optimized lysis time (adjust based on tissue quality; typically 10-15 minutes). Include additional filtration using Flowmi cell strainers (70μm) to reduce debris. Perform extra wash steps with nuclei extraction buffer to improve purity.

Quantification and Quality Control: Quantify nuclei suspensions using automated cell counters with fluorescent viability stains (Acridine Orange/Propidium Iodide). Successful isolations typically show >70% double-stained or PI-labeled nuclei. Assess RNA integrity number (RINe) when possible, though this may be unreliable in significantly degraded samples [20].

Immunostaining for Neuronal Enrichment: Incubate nuclei with primary antibody for neuronal marker NeuN (1:100 dilution) for 30 minutes on ice. Remove unbound antibody by centrifugation (400 rcf for 5 minutes). Add fluorescent secondary antibody and incubate 15 minutes in dark on ice. Wash twice to reduce background fluorescence.

Fluorescent-Activated Nuclei Sorting (FANS): Analyze samples using a cell sorter (e.g., Sony SH800Z) with appropriate laser configuration. Establish gates using unstained and secondary antibody-only controls. Sort DAPI-positive nuclei above background fluorescence threshold for neuronal populations. Collect sorted nuclei in chilled blocking buffer for downstream applications.

Cell Death Analysis in Complex Tissue Organoids

For disease modeling and drug screening applications, glioblastoma organoids (GBOs) represent a valuable platform that preserves tumor heterogeneity. The following flow cytometry protocol enables quantitative cell death analysis in these complex, dense structures [36]:

Organoid Dissociation: Generate single-cell suspensions from GBOs through combined enzymatic and mechanical dissociation. Use gentleMACs Octo Dissociator with heaters running appropriate dissociation programs.

Cell Permeabilization and Staining: Permeabilize cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes at 4°C. Stain with propidium iodide (PI, 50μg/mL) for 30 minutes in the dark. PI intercalates into fragmented DNA of dying cells.

Flow Cytometry Analysis: Analyze samples using a flow cytometer with 488nm excitation and 617nm emission detection. Identify hypodiploid cells (sub-G1 peak) as a measure of cell death. Include debris and doublet exclusion gates for accurate quantification.

Validation Methods: Confirm treatment-induced effects using complementary methods including Hoechst 33258 staining, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assays, and measurements of organoid diameter changes.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Postmortem Tissue Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclei Isolation Kits | 10X Genomics Chromium Nuclei Isolation Kit | Isolation of intact nuclei from frozen tissue | Optimize lysis time; add extra filtration steps for debris-heavy tissue |

| RNase Inhibitors | Promega RNase Inhibitor | Prevent RNA degradation during processing | Use in all buffers and wash steps (0.2 U/μL final concentration) |

| Viability Stains | Acridine Orange/Propidium Iodide; DAPI | Nuclei quantification and viability assessment | AO/PI for general assessment; DAPI for flow sorting applications |

| Cell Type Markers | Anti-NeuN Antibody | Neuronal nuclei identification and enrichment | Validate staining with positive/negative control populations |

| Dissociation Reagents | Miltenyi Nuclei Extraction Buffer | Tissue dissociation and nuclei release | Supplement with RNase inhibitors; maintain cold temperatures |

| Cell Death Assays | Propidium Iodide; LDH Assay Kits | Quantification of apoptosis/necrosis in tissue models | Combine with mechanical dissociation for dense organoids |

Immune Response Dynamics in Postmortem Tissues

Special Considerations for Neuroimmune Studies

The investigation of immune responses in postmortem neural tissues requires particular attention to PMI effects, as immune activation signatures may be especially vulnerable to postmortem alterations. Studies indicate that "PMI altered the transcriptome in the central nervous system (CNS) and blood, dysregulating pathways involved in immune response" [20]. This has profound implications for research on neuroinflammatory conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Recent research has identified specific molecular regulators of blood-brain barrier function and immune cell infiltration that may be sensitive to PMI effects. For instance, the scaffold protein IQGAP2 has been identified as a key regulator of brain endothelial cell immune privilege, with loss of IQGAP2 associated with increased leukocyte infiltration and inflammatory signatures in brain endothelial cells [37]. Alzheimer's disease tissue analyses further reveal disease-associated reductions in hippocampal IQGAP2, suggesting this molecule may represent a sensitive marker of neuroimmune status vulnerable to improper tissue processing [37].

Framework for Preserving Immune Signatures

To accurately capture immune dynamics in postmortem tissues, researchers should implement the following practices:

Standardized PMI Documentation: Record precise death-to-preservation intervals for all samples and include as covariate in statistical models. Consider stratifying analyses by PMI when possible.

Validation with Fresh Tissue Comparisons: Where feasible, validate key findings in freshly processed tissue models or surgical specimens to confirm PMI resilience of observed immune signatures.

Multi-omics Corroboration: Support transcriptomic findings of immune activation with proteomic analyses of corresponding cytokines, chemokines, and immune cell markers to distinguish transcriptional changes from protein-level immune responses.

Cell-Type-Specific Resolution: Employ single-cell or nuclei sorting approaches to resolve immune signatures in specific cell populations, as bulk tissue analyses may mask cell-type-specific effects of PMI on immune gene expression.

The reliability of research findings from postmortem tissues depends critically on implementing a standardized framework that acknowledges and mitigates the substantial effects of postmortem interval on molecular integrity. Based on current evidence, the following best practices are recommended:

Minimize PMI Whenever Possible: While not always feasible, efforts to reduce death-to-preservation intervals below 3 hours can significantly improve detection of disease-specific signatures, particularly for neuronal and immune transcripts.

Implement Rigorous Quality Control: Establish minimum quality thresholds for RNA integrity, nuclei viability, and immunostaining specificity. Document and report these metrics for all experiments.

Account for PMI in Study Design: Match comparison groups by PMI, include PMI as a covariate in statistical models, and consider PMI-matched control tissues for disease studies.

Select Appropriate Preservation Methods: For immune and transcriptional studies, prioritize rapid freezing at -80°C or colder with RNase protection for bulk analyses, or immediate nuclei isolation for single-cell applications.

Validate Key Findings: Where possible, corroborate findings from postmortem tissues with living tissue models, animal studies, or human surgical specimens to ensure biological validity.

As research methodologies advance, the integration of standardized PMI-aware processing frameworks will enhance the translational potential of postmortem tissue studies, particularly in the realm of neuroimmunology and neurodegenerative disease research.