Divergent Pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron Variants: Insights from 3D Respiratory Models

This article synthesizes current research comparing the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variants, with a specific focus on findings from advanced 3D respiratory models.

Divergent Pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron Variants: Insights from 3D Respiratory Models

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research comparing the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variants, with a specific focus on findings from advanced 3D respiratory models. It explores the foundational mechanisms of viral entry and replication, detailing how Delta variant's efficient TMPRSS2-mediated fusion and syncytia formation contrast with Omicron's altered cellular tropism. The review covers methodological applications of human airway epithelial (HAE) cultures and computational analyses for investigating host-pathogen interactions. It further addresses troubleshooting in variant-specific research and validates in vitro findings against animal model and human clinical data. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this analysis provides a critical framework for understanding variant-specific pathogenesis and informs the development of targeted therapeutics.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Variant Pathogenicity: From Spike Protein to Cellular Entry

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern, particularly Delta and Omicron, represented a significant shift in the pandemic landscape, characterized by distinct mutations in the viral spike protein. These mutations critically alter the virus's infectivity, pathogenicity, and immune evasion capabilities. This guide provides a comparative computational analysis of the structural and functional consequences of Delta and Omicron spike protein mutations. We synthesize data from molecular dynamics simulations, binding affinity assessments, and ex vivo replication studies to objectively compare their mechanisms of action. The analysis is framed within research utilizing primary human nasal cultures and 3D respiratory models, offering insights relevant to therapeutic and vaccine development.

The evolution of SARS-CoV-2 has been marked by the emergence of variants with distinct pathogenic profiles, largely driven by mutations in the spike (S) protein. The Delta and Omicron variants represent two pivotal points in this evolution. The Delta variant is associated with more severe disease and a degree of immune evasion, whereas the Omicron variant demonstrates dramatically increased transmissibility but reduced intrinsic severity. These divergent clinical outcomes are rooted in fundamental differences in their spike protein structures and dynamics. This review leverages computational analyses and data from primary human respiratory models to dissect the molecular basis for these differences, providing a comparative guide for researchers and drug developers.

Mutational Landscapes and Their Structural Consequences

The Delta and Omicron variants possess unique and complex sets of mutations that define their behavior.

Key Mutations and Their Functional Roles

The following table summarizes the major spike protein mutations and their documented impacts for each variant.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Spike Protein Mutations in Delta and Omicron Variants

| Feature | Delta Variant (B.1.617.2) | Omicron Variant (B.1.1.529) |

|---|---|---|

| Notable Mutations | T478K, L452R, P681R, D614G [1] [2] | K417N, N440K, G446S, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H [3] [4] [2] |

| Immune Evasion | Moderate; reduced susceptibility to neutralizing antibodies [1] | High; significant escape from vaccine- and infection-elicited antibodies [2] |

| Spike Protein Stability | Lower stability; mutations disturb complex stability [3] | Higher stability; unique mutational pattern enhances stability [3] [5] |

| Entry Pathway | Primarily TMPRSS2-dependent, membrane fusion pathway [6] | Increased cathepsin-dependent, endosomal entry pathway [6] |

Computational Analysis of Structural Stability

Protein Contact Network (PCN) analysis, which models protein structures as networks of amino acid interactions, reveals that Omicron’s mutations lead to a unique mutational pattern with distinct structural consequences compared to Alpha and Delta variants [5]. Molecular Dynamic (MD) simulations further show that while mutations in both variants disturb the stability of the spike protein or its complex with the hACE-2 receptor, the Delta variant has a greater instability impact [3]. This observed instability in the Delta spike protein complex may be linked to its reported higher pathogenicity.

Omicron’s stability is partly achieved through a trade-off. The D614G mutation weakens the interaction between the S1 and S2 subunits of the spike protein. However, several other Omicron-specific mutations (T547K, H655Y, N764K, N856K, N969K, L981F) enhance the S2-S1 interaction, compensating for the destabilizing effect of D614G and contributing to the variant's overall fitness [7].

Comparative Experimental Protocols and Data

To understand the real-world implications of these structural differences, researchers employ advanced ex vivo models and computational techniques.

Ex Vivo Replication Kinetics in Human Respiratory Tissues

A critical experimental protocol for evaluating variant-specific pathogenicity involves culturing human bronchus and lung tissue explants and directly comparing viral replication kinetics [6].

Table 2: Replication Capacity of SARS-CoV-2 Variants in Human Ex Vivo Cultures

| Variant | Replication in Human Bronchi | Replication in Human Lung Parenchyma | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | Baseline | Baseline | [6] |

| Delta | Significantly higher than WT at 72h | Similar to or slightly reduced vs. WT | [6] |

| Omicron | Faster than all other VOCs at 24h and 48h; ~70-fold higher than WT | Significantly reduced replication compared to WT and Delta | [6] |

This data provides a clear biological correlate for epidemiological observations: Omicron's high replication in the upper airway facilitates transmission, while its poor replication in the lungs is a key factor underlying its reduced severity [6]. Complementary research in primary human nasal cultures confirms that Omicron is the fastest-replicating variant in the upper airway, while Delta is the most cytopathic, causing the most damage to the respiratory epithelium, including loss of ciliary function [8].

Computational Evaluation of Binding Dynamics

The binding affinity between the spike Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) and the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (hACE-2) receptor is a critical determinant of infectivity. Computational studies use molecular docking and dynamics simulations to evaluate this.

Methodology Overview:

- Structures: The crystal structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein in complex with hACE-2 (e.g., PDB ID: 7DF4) is obtained [3].

- Mutagenesis: Mutations for each variant are introduced into the wild-type spike protein structure using tools like the rotamer library in UCSF Chimera [3].

- Docking: The spike RBD for each variant is docked to hACE-2 using servers like HADDOCK [3].

- Simulations & Analysis: Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (e.g., using AMBER) are run on the docked complexes. Post-simulation analysis, such as calculating binding free energy with methods like MM/PBSA, reveals the strength and stability of the interaction [3] [9].

Findings from these analyses show that the Omicron variant has high receptiveness towards hACE-2 compared to the Delta variant, contributing to its increased transmission [3]. Interestingly, a computational analysis introducing a Binding Influence Score found that most of Omicron's RBD mutations, except for N501Y, actually reduce ACE2 binding affinity when considered in isolation. However, this reduced affinity is offset by other mutations that dramatically increase the propensity of the spike protein to adopt an "open" conformation, thereby increasing the chances of initiating contact with ACE2 [4].

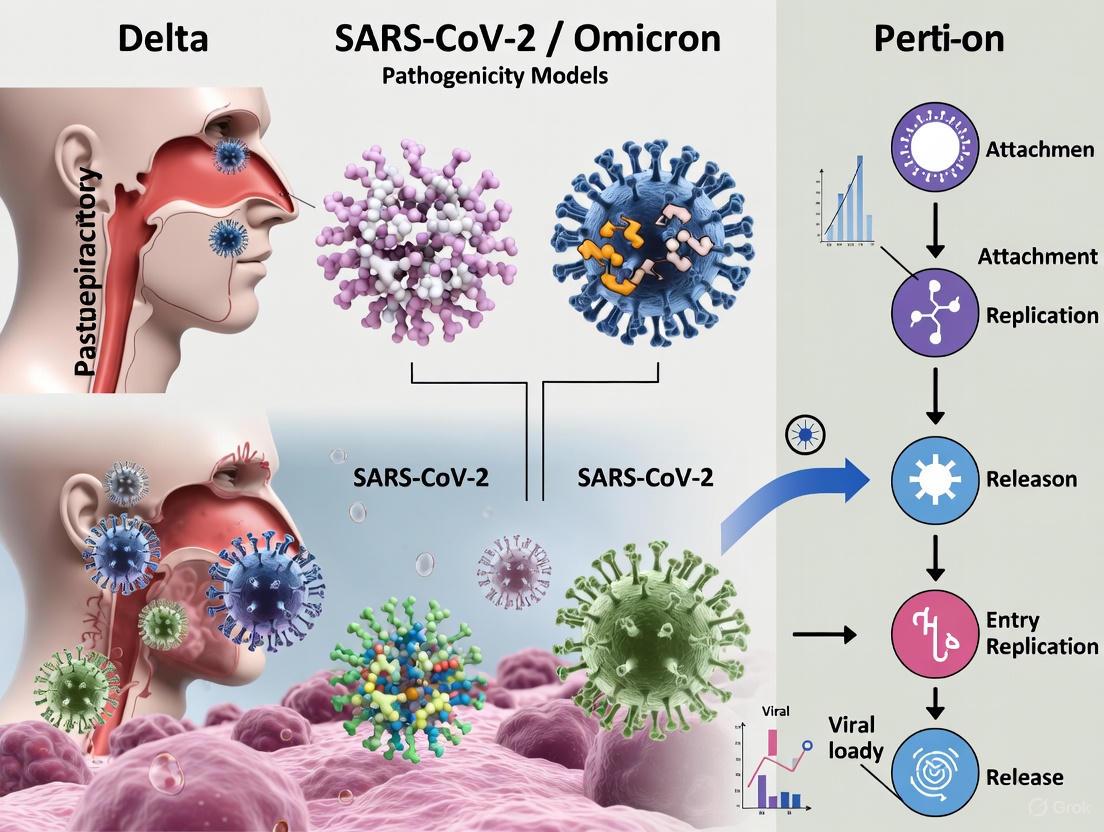

Diagram 1: Relationship between spike protein mutations and the pathogenic profiles of Delta and Omicron variants. Mutations drive differences in stability, binding, and entry, which ultimately determine tissue tropism and clinical severity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Research into the structural biology and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 variants relies on a suite of specialized reagents and model systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Models for Variant Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Relevance to Variant Research |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Human Nasal Cultures (ALI) | Models human upper respiratory infection; assesses viral replication, cytopathicity, and host responses [8]. | Directly demonstrated Omicron's fast replication and Delta's high cytopathicity in the human airway [8]. |

| Ex Vivo Human Bronchus/Lung Explants | Provides a physiologically relevant model of the human lower respiratory tract [6]. | Showcased Omicron's tropism for the bronchus and impaired replication in lung tissue, explaining reduced severity [6]. |

| hACE-2 Expressing Cell Lines | Cell lines engineered to express the human ACE2 receptor for in vitro infection studies. | Fundamental for testing viral entry efficiency, tissue tropism, and neutralization assays across variants. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (AMBER, GROMACS) | Simulates physical movements of atoms and molecules over time to explore structural stability and interactions [3]. | Revealed differences in spike protein stability and RBD-hACE2 binding energy between Delta and Omicron [3] [9]. |

| Molecular Docking Servers (HADDOCK) | Computationally predicts the preferred orientation of a protein (spike) when bound to its receptor (hACE-2) [3]. | Used to evaluate how specific mutations alter the binding interface and affinity of the spike protein [3] [4]. |

The computational and experimental data clearly delineate the structural and functional divergence between the Delta and Omicron spike proteins. The Delta variant's profile—characterized by moderate binding affinity, TMPRSS2-driven entry, and efficient lung replication—underpins its heightened pathogenicity. In contrast, the Omicron variant's profile—featuring a stabilized spike, altered entry pathway, and superior upper respiratory replication—accounts for its hyper-transmissibility but attenuated severity. For researchers and drug developers, these findings underscore the necessity of targeting conserved viral regions or host factors, such as TMPRSS2, to develop broad-spectrum therapeutics and vaccines resilient to ongoing viral evolution.

The cellular entry of SARS-CoV-2 is a critical determinant of viral tropism, transmission, and pathogenesis. This process is mediated primarily by the viral spike (S) protein and its interactions with host cell receptors [10]. While angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) serves as the primary entry receptor, its affinity alone does not fully explain the distinct pathogenic profiles observed among SARS-CoV-2 variants [10] [11]. The Omicron variant, characterized by numerous mutations in its spike protein, exhibits significantly altered receptor binding properties compared to earlier variants like Delta [12] [13]. These differences are particularly evident in their utilization of alternative receptors and entry pathways, including those involving Neuropilin-1 (NRP1) and different cellular proteases [14] [11]. Understanding these variant-specific interactions is crucial for explaining their differing clinical manifestations and for developing targeted therapeutic interventions. This review synthesizes current evidence on the differential binding affinities of SARS-CoV-2 variants to ACE2 and NRP1, and explores how these interactions shape viral entry pathways and ultimately, disease outcomes.

Quantitative Comparison of Variant-Receptor Interactions

The Delta and Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2 exhibit distinct quantitative profiles in their interactions with host receptors and subsequent entry pathways. These differences, summarized in the table below, significantly influence their cellular tropism and pathogenicity.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Delta and Omicron Variant-Receptor Interactions and Entry Pathways

| Parameter | Delta Variant (B.1.617.2) | Omicron Variant (B.1.1.529) | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACE2 Binding Affinity | High affinity, efficient utilization | Enhanced binding strength compared to Delta [12] | Surface plasmon resonance and pseudovirus entry assays [12] |

| NRP1 Utilization | Efficient utilization of NRP1-mediated entry | Reduced NRP1 dependence [13] | Blocking antibody assays and infection studies in NRP1-expressing cells [13] [11] |

| Primary Entry Route | TMPRSS2-mediated plasma membrane fusion [13] | Cathepsin-dependent endosomal entry [13] | Infection studies with protease inhibitors in Calu-3 and Caco-2 cells [13] |

| Cell Entry Rate | High cell entry rate | Significantly lower cell entry rate [13] | Mathematical modeling of infection kinetics in lung and intestinal cell lines [13] |

| Fusogenicity | High syncytia formation [15] [16] | Attenuated fusogenicity (BA.1/BA.2); Enhanced in BA.5 [15] | Quantitative syncytia formation assays in VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells [15] |

| Innate Immune Activation | Moderate cytokine production | Stronger cytokine production rate in infected cells [13] | Transcriptomic analysis of infected cells and mathematical modeling [13] |

Table 2: Comparative Pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Variants in Respiratory Models

| Variant | In Vitro Replication (Calu-3) | Barrier Disruption (Airway-on-a-Chip) | In Vivo Pathogenicity (Hamster Model) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancestral (B.1.1) | High [15] | Severe respiratory epithelial and endothelial barrier disruption [15] | Severe weight loss, respiratory dysfunction [15] |

| Delta | High (similar to ancestral) [17] | Not fully characterized | Augmented lung pathology, immune cell infiltration [17] |

| Omicron BA.1 | Lower replication rate [15] | Moderate disruption [15] | Minimal weight change, milder respiratory dysfunction [15] |

| Omicron BA.2 | Intermediate between BA.1 and BA.5 [15] | Moderate disruption [15] | Minimal weight change, milder respiratory dysfunction [15] |

| Omicron BA.5 | Comparable to ancestral virus [15] | Enhanced disruption compared to BA.1/BA.2 [15] | Moderate weight loss, slightly higher than other Omicron subvariants [15] |

Key Experimental Methodologies in Receptor Binding Studies

Mathematical Modeling of Viral Entry Dynamics

Mathematical modeling has provided crucial insights into the differential entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 variants. A refined integro-differential equation model was fitted to experimental data from Delta and Omicron infections in Caco-2 (human intestinal epithelium model) and Calu-3 (lung epithelium model) cell lines [13]. The experimental data included infectious virus titers determined by TCID50 assays at 8, 24, and 48 hours post-infection (hpi), and intracellular viral RNA measurements using RT-qPCR at 2, 8, 24, and 48 hpi [13]. The model quantified variant- and cell-line-specific parameters, particularly the cell entry rate and cytokine production rate, revealing that Omicron has a significantly lower cell entry rate but triggers a stronger innate immune response in infected cells compared to the Delta variant [13].

Airway-on-a-Chip Model for Barrier Function Assessment

Advanced 3D respiratory models have been instrumental in quantifying variant-specific effects on tissue integrity. In one methodology, researchers utilized airway-on-a-chip devices to evaluate the capacity of different Omicron subvariants to disrupt respiratory epithelial and endothelial barriers [15]. The experimental workflow involved infecting the airway channel of the device with different variants and subsequently measuring the amount of virus that migrated to the blood vessel channel [15]. This approach allowed for quantitative assessment of barrier disruption by different variants. Results demonstrated that BA.5 caused more severe barrier damage compared to BA.1 and BA.2, though less than the ancestral B.1.1 strain [15]. Additionally, decreased expression of CLDN5, a crucial component for sustaining vascular endothelial barrier integrity, was observed in endothelial cells infected with B.1.1 and BA.5 variants [15].

Structural and Biochemical Analysis of NRP1 Interactions

The interaction between SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and NRP1 has been characterized through structural, biochemical, and molecular dynamics studies. These investigations revealed that furin-mediated cleavage at the S1/S2 junction of the spike protein exposes a C-terminal motif (RRAR) that conforms to the C-end Rule (CendR) [14] [11]. This exposed motif binds with high affinity to the b1 domain of NRP1 [14]. Crystallographic data demonstrate that the terminal arginine residue (R685) of the spike protein forms stable electrostatic and cation-π interactions with conserved aromatic residues within NRP1's b1 domain, specifically Y297, W301, and Y353 [14]. Functional validation through mutagenesis confirmed that deletion of the RRAR motif or replacement of R685 severely disrupts spike-NRP1 interaction, significantly reducing viral infectivity [14].

Molecular Mechanisms of Receptor-Mediated Entry

ACE2-Dependent Entry Pathways

The primary pathway for SARS-CoV-2 entry begins with spike protein binding to ACE2, followed by conformational changes that enable membrane fusion [10]. The spike protein is cleaved by host proteases into S1 and S2 subunits, with the S1 subunit containing the receptor-binding domain (RBD) that directly engages ACE2 [10]. Upon ACE2 binding, the spike protein undergoes additional conformational changes that expose the S2' cleavage site, which is processed by proteases such as TMPRSS2 at the cell surface or cathepsin L in endosomes [10]. This proteolytic activation releases the fusion peptide, initiating fusion pore formation and viral entry [10]. Variants differ significantly in their preferred entry route: Delta utilizes TMPRSS2-mediated plasma membrane fusion more efficiently, while Omicron favors cathepsin-dependent endosomal entry [13].

NRP1 as a Critical Co-receptor

NRP1 serves as a crucial co-receptor that enhances SARS-CoV-2 infectivity, particularly in cell types with low ACE2 expression [14] [11]. Unlike ACE2, NRP1 does not mediate initial viral attachment but rather facilitates viral internalization through endocytic pathways resembling macropinocytosis [14]. The mechanism depends on prior furin cleavage of the spike protein, which exposes the C-terminal RRAR motif [11]. This motif then binds to the b1 domain of NRP1, significantly potentiating viral infectivity [11]. Blocking this interaction with specific monoclonal antibodies reduces viral infection by approximately 40% in cell culture models [11]. The RRAR motif shows remarkable evolutionary conservation (>98%) across variants circulating in Mexico, suggesting NRP1 represents a stable therapeutic target less vulnerable to viral mutation [14].

Differential Innate Immune Activation

Beyond their roles in viral entry, ACE2 and NRP1 interactions trigger variant-specific innate immune responses. Mathematical modeling of variant infections in human epithelial cells indicates that Omicron triggers a stronger cytokine production rate in infected cells compared to Delta [13]. This enhanced innate immune activation ultimately renders uninfected cells more resistant to viral infection, potentially explaining the attenuated pathogenicity of Omicron despite its high transmissibility [13]. Transcriptomic analyses of infected lung tissues further support these findings, showing that Delta variant infection leads to more pronounced induction of immune mediators and metabolic enzymes such as Arg-1 and IDO1 compared to Omicron infection [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying SARS-CoV-2 Receptor Interactions

| Reagent / Method | Specific Application | Key Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudovirus Systems | Viral entry assays | Enables study of viral entry mechanisms without requiring BSL-3 facilities [11] |

| VeroE6/TMPRSS2 Cells | Viral propagation and titration | Cell line optimized for efficient SARS-CoV-2 isolation and growth [15] [16] |

| Calu-3 Cell Line | In vitro infection models | Human lung epithelial cell model expressing ACE2 and TMPRSS2 [13] |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | In vitro infection models | Human intestinal epithelium model expressing ACE2 and TMPRSS2 [13] |

| Airway-on-a-Chip | Barrier function assessment | Microfluidic device modeling human respiratory epithelial-endothelial interface [15] |

| NRP1 Blocking Antibodies | Receptor function studies | Specifically inhibits spike protein binding to NRP1 b1 domain [11] |

| TCID50 Assay | Viral quantification | Measures infectious virus titers in cell culture supernatants [13] |

| siRNA against NRP1 | Gene silencing studies | Evaluates NRP1 role in viral entry through knockdown approaches [14] |

The differential binding affinities of SARS-CoV-2 variants to host receptors ACE2 and NRP1 fundamentally shape their entry pathways and pathogenic profiles. While the Delta variant exhibits efficient ACE2 binding and TMPRSS2-mediated plasma membrane fusion, the Omicron variant has evolved enhanced ACE2 binding affinity but reduced efficiency in TMPRSS2 utilization and NRP1-mediated entry. These differences in receptor preference correspond to Omicron's shift toward endosomal entry pathways and its attenuated fusogenicity, particularly in early subvariants. The conservation of the NRP1-binding RRAR motif across variants, coupled with the stable expression of NRP1 in human tissues, highlights its potential as a therapeutic target. Future research should focus on characterizing receptor interactions of emerging variants and developing intervention strategies that simultaneously target multiple entry pathways to overcome viral evolution.

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern, particularly Delta and Omicron, revealed significant divergences in viral pathogenesis. A critical factor underlying these differences is altered cellular tropism, driven by how each variant utilizes host cell entry mechanisms. This guide objectively compares the TMPRSS2 utilization and membrane fusion efficiency of the Delta and Omicron variants, synthesizing key experimental findings from respiratory and intestinal models. The core distinction lies in Omicron's shift away from TMPRSS2-dependent plasma membrane fusion towards endocytic pathway entry, a fundamental reprogramming with direct implications for viral pathogenicity and tissue-specific replication [18] [19].

Experimental Protocols for Key Findings

Viral Replication Kinetics Assay

Objective: To compare the replication efficiency of Delta and Omicron variants in different cell lines modeling the human respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts [18] [19].

- Cell Lines: VeroE6/TMPRSS2 (kidney epithelium, engineered), Calu-3 (lung epithelium, endogenous TMPRSS2), Caco-2 (colon epithelium, endogenous TMPRSS2), and primary human nasal epithelial cultures (hNECs) [18] [19].

- Infection: Cells are inoculated with a standardized multiplicity of infection (MOI) (e.g., 0.1 TCID50 for VeroE6/TMPRSS2 and Caco-2; 0.5 for Calu-3). After a 1-2 hour adsorption period, the inoculum is removed, cells are washed, and fresh medium is applied [19] [20].

- Data Collection: Supernatants are collected at multiple time points post-infection (e.g., 1, 12, 24, 48, 72 hours). Viral load is quantified via RT-qPCR targeting the SARS-CoV-2 E gene, and infectious virus titers are determined by 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay [18] [19].

- Key Outcome: Replication kinetics are plotted over time to compare peak viral titers and growth rates between variants in each cell type.

Viral Entry Pathway Inhibition Assay

Objective: To delineate the specific entry pathways (TMPRSS2-mediated vs. endosomal) used by Delta and Omicron [19].

- Inhibitors: Cells are pre-treated with specific chemical inhibitors:

- Infection and Analysis: Treated cells are infected with Delta or Omicron pseudotyped viruses or live isolates. The extent of infection is measured 24-48 hours post-infection via luciferase activity (for pseudoviruses) or viral RNA quantification. The percentage inhibition of entry by each drug is calculated relative to an untreated infected control [19].

- Key Outcome: The differential sensitivity to camostat versus bafilomycin A1/chloroquine indicates the preferred entry route for each variant.

Cell-Cell Fusion Assay

Objective: To evaluate the syncytium-forming capability of the Delta and Omicron spike proteins, a proxy for membrane fusion efficiency [18] [19].

- Method: VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells are transfected with a plasmid encoding Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP). Subsequently, the cells are infected with live Delta or Omicron virus, or transfected with spike protein-expression plasmids.

- Visualization and Quantification: At 24, 48, and 72 hours post-infection/transfection, cells are imaged using fluorescence microscopy. Syncytia formation—multinucleated giant cells resulting from spike-mediated fusion—is assessed by counting the number of nuclei within GFP-positive fused cell areas [18] [19].

- Key Outcome: The relative extent and kinetics of syncytia formation provide a direct measure of the fusogenicity of each variant's spike protein.

Comparative Data Analysis

The experimental protocols yield consistent, quantifiable data highlighting the distinct biological behaviors of the Delta and Omicron variants.

Table 1: Comparative Replication and Entry of SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron Variants

| Parameter | Delta Variant | Omicron Variant | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Replication in Calu-3 (Lung) | High (≥1 log10 higher RNA) [18] | Significantly lower [18] | Live virus infection [18] |

| Replication in Caco-2 (Gut) | High [18] | Lower (∼1 log10 less infectious virus) [18] | Live virus infection [18] |

| Replication in hNECs (Nose) | Similar to Omicron [18] | Similar to Delta [18] | Live virus infection [18] |

| TMPRSS2 Usage | Efficient [18] [19] | Inefficient [18] [19] | Inhibition by camostat [19] |

| Endosomal Entry | Secondary pathway [19] | Primary pathway [18] [19] | Inhibition by bafilomycin A1 [19] |

| Spike Cleavage (S1/S2) | Highly efficient [18] | Less efficient [18] | Analysis of purified virions [18] |

| Syncytium Formation | Robust [18] [19] | Substantially impaired [18] [19] | Cell-cell fusion assay [18] [19] |

Table 2: Summary of Pathogenicity-Associated Findings from Animal Models

| Observation | Delta Variant | Omicron Variant | Model System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Pathology | Enhanced damage, immune cell infiltration [17] | Reduced damage [17] | Golden Syrian Hamster [17] |

| Viral Titers in Lungs | Higher [21] [17] | Lower [21] [17] | K18-hACE2 Mice / GSH [21] [17] |

| Immune/Inflammatory Gene Upregulation | Marked upregulation of cytokines, chemokines [21] | Muted immune response [21] | K18-hACE2 Mice [21] |

| Overall Pathogenicity Ranking | High [21] | Lower [21] | Comparative analysis [21] |

Mechanisms Underlying Cellular Tropism

The data presented above can be traced to fundamental differences in how the Delta and Omicron spike proteins interact with host cell factors. The following diagram synthesizes the core mechanistic pathways that dictate variant-specific cellular tropism.

The molecular basis for the pathway divergence illustrated in Figure 1 is well-established. Omicron's less efficient cleavage of its spike protein at the S1/S2 site limits its ability to be activated by TMPRSS2 at the plasma membrane [18]. This, combined with its mutations, causes a shift in tropism away from TMPRSS2-rich cells like lung alveolar type II cells and toward cells where endocytic entry is more prevalent [18]. Consequently, Omicron's impaired syncytia formation is a direct result of its reduced reliance on TMPRSS2, a protease that promotes efficient cell-surface fusion [18] [19]. This attenuated fusogenicity is a key contributor to its reduced pathogenicity observed in models [21] [17]. Mathematical models further confirm that this difference cannot be explained by entry efficiency alone; Omicron also triggers a stronger innate immune response in infected cells, further curtailing its replication in certain cell types [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit

To investigate viral tropism and entry mechanisms, researchers rely on a specific set of reagents and model systems. The following table details key solutions used in the studies cited herein.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Models for Studying Viral Entry

| Reagent / Model | Function in Research | Key Application/Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Calu-3 Cell Line | Model of human lung epithelium with robust endogenous TMPRSS2 expression. | Demonstrates Delta's superior replication in TMPRSS2+ lung cells [18] [19]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Model of human intestinal epithelium expressing ACE2 and TMPRSS2. | Highlights variant-specific tropism differences in the gut [18] [20]. |

| VeroE6/TMPRSS2 Cells | Engineered kidney cell line that overexpresses human TMPRSS2. | Used to enhance virus isolation and study TMPRSS2-dependent entry [19]. |

| Camostat Mesylate | Small-molecule inhibitor of TMPRSS2. | Potently inhibits Delta entry but not Omicron, defining entry pathway preference [19]. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | Inhibitor of endosomal acidification, blocking endosomal entry. | Inhibits both Delta and Omicron, confirming Omicron's endosomal dependence [19]. |

| Primary hNEC Cultures | Physiologically relevant 3D model of the human upper airway. | Shows both variants replicate equally well in the nose, explaining high transmissibility [18]. |

The differential pathogenicity and transmission efficiency of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern, particularly Delta and Omicron, have been defining characteristics of the COVID-19 pandemic. A key to understanding these differences lies in elucidating the early infection kinetics—the initial viral entry and replication dynamics within the respiratory epithelium. This comparative guide objectively analyzes the performance of these variants using advanced 3D respiratory models that closely mimic human physiology. These experimental systems, including air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures, organoids, and lung-on-a-chip technologies, provide unprecedented insight into viral tropism, replication efficiency, and host response patterns. By synthesizing data from controlled infection studies, this review establishes a foundational framework for understanding variant-specific pathogenesis and identifies critical experimental parameters for drug development professionals evaluating antiviral efficacy.

Comparative Viral Kinetics of Delta and Omicron Variants

Viral Entry Mechanisms and Cellular Tropism

The fundamental divergence between Delta and Omicron variants begins at the point of cellular entry, where distinct pathway preferences significantly influence tissue tropism and disease presentation.

Delta Variant Entry: Delta predominantly utilizes the TMPRSS2-dependent pathway, which facilitates direct fusion at the plasma membrane. This entry mechanism favors infection of cells with high TMPRSS2 expression, particularly in the lower respiratory tract where this protease is abundantly expressed. The reliance on TMPRSS2 makes Delta highly effective at infecting lung tissues but limits its entry options in cell types with low TMPRSS2 expression [22] [16].

Omicron Variant Entry: Omicron employs a dual-entry strategy with enhanced efficiency in TMPRSS2-independent pathways, primarily through endosomal uptake. This allows Omicron to infect a broader range of cell types, including those with limited TMPRSS2 expression. The variant's spike protein mutations optimize it for ACE2 binding affinity while reducing TMPRSS2 dependence, explaining its preferential replication in upper airway epithelia compared to lung tissue [12] [22].

Cellular Tropism Differences: Single-cell RNA sequencing analyses reveal that SARS-CoV-2 preferentially enters via ciliated cell precursors, with infected mature ciliated cells then signaling to basal cells to induce rapid differentiation. This creates a feedforward loop of infection that is mitigated by cell-cell communication before interferon signaling begins approximately three days post-infection [23]. Age significantly influences cellular tropism, with paediatric nasal epithelial cultures showing higher infection of goblet cell types, while adult and older adult cultures demonstrate increased susceptibility in secretory cell types [24].

Replication Dynamics in Respiratory Compartments

The replication efficiency of Delta and Omicron variants differs dramatically between upper and lower respiratory compartments, explaining their distinct clinical manifestations.

Nasal Epithelium Replication: Omicron demonstrates a significant replication advantage in nasal epithelial cells compared to Delta. Mathematical modeling of viral kinetics indicates Omicron has approximately 200-fold higher infectivity in nasal cells, though its virus production rate is approximately 100-fold lower than Delta. This results in a higher basic reproduction number (R₀) and faster growth rate for Omicron in upper airways, explaining its substantial transmission advantage [22] [24].

Lung Tissue Replication: In stark contrast to its nasal replication profile, Omicron shows impaired replication capacity in lung cells compared to Delta. Viral kinetic models demonstrate Delta has a significantly higher virus production rate in lung tissues, leading to more severe parenchymal infection and lung pathology. This replication deficiency in lower airways provides a mechanistic explanation for Omicron's reduced disease severity despite its heightened transmissibility [22] [17].

Age-Dependent Replication Patterns: Infected older adult nasal epithelial cultures produce >800-fold higher titers of infectious particles compared to paediatric cultures at 72 hours post-infection. This age-associated replication efficiency correlates with broader cellular tropism in older adults, where 11 different cell types show infection compared to only 3 cell types in paediatric cultures [24].

Table 1: Comparative Viral Kinetic Parameters of Delta and Omicron Variants

| Parameter | Delta Variant | Omicron Variant | Experimental System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infectivity in Nasal Cells | Baseline | ~200-fold increase | Primary human nasal epithelial cells (hNECs) [22] |

| Virus Production Rate in Nasal Cells | Baseline | ~100-fold decrease | Primary human nasal epithelial cells (hNECs) [22] |

| Basic Reproduction Number (R₀) in Nasal Cells | Lower | Significantly higher | Viral kinetics modeling [22] |

| Replication in Lung Cells | Highly efficient | Less efficient | Calu-3 lung cells [22] |

| Primary Entry Pathway | TMPRSS2-dependent | TMPRSS2-independent endosomal entry | Viral entry inhibition assays [22] |

| Preferred Infection Site | Lower respiratory tract | Upper respiratory tract | Multi-model analysis [22] [24] |

Experimental Models for Viral Kinetics Assessment

Advanced 3D Respiratory Model Systems

The physiological relevance of experimental models critically influences the accuracy of viral kinetics assessment. Conventional 2D cell cultures and animal models have significant limitations in recapitulating human-specific responses to infection.

Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) Cultures: These systems cultivate human bronchial epithelial cells on transwell membranes where they differentiate into a pseudostratified mucociliary epithelium that closely mimics native airway tissue. ALI cultures contain all major airway cell types, including basal, goblet, club, and ciliated cells, as well as ionocytes. This model has proven exceptionally valuable for studying early SARS-CoV-2 infection events, demonstrating that the virus triggers rapid differentiation of basal cells and creates a feedforward loop of infection [23] [25]. ALI cultures from different age donors have revealed age-specific responses, with older adult cultures showing increased viral spread and production compared to paediatric cultures [24].

Lung Organoids: These self-organizing 3D structures derived from pluripotent or adult stem cells recapitulate key aspects of lung development and organization. Organoids model both proximal and distal lung regions and can include multiple cell types present in native tissue. They have been successfully employed for SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis studies and antiviral drug testing, leading to the identification of several inhibitors including imatinib, mycophenolic acid, and quinacrine dihydrochloride [25]. A limitation of conventional organoid systems is the general absence of vascularization and immune components, which restricts study of immune cell recruitment and systemic drug delivery [25].

Lung-on-a-Chip Systems: These microfluidic devices incorporate human lung epithelial cells and microvascular endothelial cells in parallel channels separated by a porous membrane. The platform allows application of mechanical forces mimicking breathing motions and perfusion of immune cells through the vascular channel. This sophisticated system has demonstrated high fidelity in modeling human disease responses and strong predictive value for drug efficacy [25] [26]. Lung-on-a-chip technology has revealed complex interactions between SARS-CoV-2 infection and endothelial dysfunction, providing insights into the vascular complications of COVID-19 [25].

3D-Bioprinted Airway Models: Emerging bioprinting technologies now enable creation of multilayered airway constructs with endothelial cells, extracellular matrix, and lung epithelial cells in precise anatomical arrangements. These models support long-term culture and allow study of viral infection at the air-exposed epithelium alongside drug delivery through the vascular compartment. 3D-bioprinted models maintain tissue integrity for extended periods, facilitating time-course studies of viral pathogenesis and therapeutic interventions [26].

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Respiratory Model Systems

| Model System | Key Advantages | Limitations | Applications in Viral Kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALI Cultures | High differentiation state; mucociliary functions; appropriate cell composition | Lack vascular and immune components; donor-dependent variability | Early infection dynamics; cellular tropism; age-specific responses [23] [24] |

| Lung Organoids | 3D architecture; stem cell functionality; disease modeling | Limited standardization; closed architecture prevents apical infection | Viral pathogenesis; antiviral screening; host-pathogen interactions [25] |

| Lung-on-a-Chip | Vascular perfusion; mechanical forces; immune cell recruitment | Complex manufacturing; low throughput; cost | Complex host responses; drug delivery; immune cell recruitment [25] [26] |

| 3D-Bioprinted Models | Precise architectural control; natural ECM; long-term culture | Specialized equipment required; optimization challenges | Antiviral efficacy testing; barrier function studies; chronic infection [26] |

Standardized Infection Methodologies

Experimental consistency across studies requires careful standardization of infection protocols, which significantly influence observed viral kinetics and host responses.

Viral Inoculation Parameters: Most ALI studies employ inoculation doses ranging from 0.01 to 0.05 MOI (multiplicity of infection) with incubation periods of approximately 1 hour at 37°C. Following inoculation, the viral solution is removed and replaced with culture medium, with samples typically collected at 24-hour intervals for up to 72-96 hours post-infection. These parameters ensure reproducible infection while maintaining tissue viability [23] [24].

Viral Load Quantification: Standard assessment includes infectious titer measurement via plaque assays and viral genome quantification through RT-qPCR targeting genes such as the E gene. Advanced studies incorporate single-cell RNA sequencing to map viral transcripts to specific cell types, and immunofluorescence staining for viral proteins (dsRNA, spike protein) to visualize spatial distribution of infection [22] [24].

Pathway Inhibition Studies: Specific entry pathways are delineated using pharmacological inhibitors including Camostat mesylate (TMPRSS2 inhibitor) and Amphotericin B (inhibitor of endosomal restriction factors). Pre-treatment with these compounds for 2 hours prior to infection, with maintained presence throughout experiments, enables dissection of variant-specific entry mechanisms [22].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Respiratory Viral Kinetics Studies

| Reagent/Cell Type | Specification | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells (HBECs) | Commercially available (e.g., Lonza); donor-matched options | Differentiation in ALI culture to form pseudostratified epithelium for infection studies [23] |

| Calu-3 Cells | Human lung adenocarcinoma cell line | Model for lung epithelial infection; expresses ACE2 and TMPRSS2 [22] [27] |

| Vero-E6/TMPRSS2 Cells | Engineered Vero-E6 cells overexpressing TMPRSS2 | Viral stock production and titration; enhances isolation of certain variants [16] |

| Camostat Mesylate | Serine protease inhibitor (50µM working concentration) | Inhibition of TMPRSS2-dependent viral entry; mechanistic studies [22] |

| Amphotericin B | Antifungal agent (1µM working concentration) | Inhibition of endosomal restriction factors; enhances TMPRSS2-independent entry [22] |

| Anti-dsRNA Antibody | monoclonal antibody (e.g., J2 clone) | Immunofluorescence detection of viral replication complexes [24] |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

SARS-CoV-2 Viral Entry Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the divergent entry mechanisms employed by Delta and Omicron variants, which underlie their distinct tissue tropism and replication dynamics:

Standardized Workflow for Viral Kinetics Studies

The following diagram outlines a representative experimental workflow for assessing viral kinetics in advanced 3D respiratory models:

The comparative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 variant infection kinetics reveals that fundamental differences in viral entry mechanisms translate to distinct replication patterns across respiratory compartments. Delta's TMPRSS2-dependent entry and enhanced lung replication capacity explain its association with more severe pulmonary disease, while Omicron's endosomal entry preference and superior nasal epithelial replication underpin its heightened transmissibility but reduced severity. Advanced 3D respiratory models provide indispensable platforms for elucidating these dynamics, with each system offering unique advantages for specific research applications. The continued refinement of these models, particularly through incorporation of immune components and age-diverse epithelia, will further enhance their predictive value for both variant characterization and therapeutic development. As SARS-CoV-2 continues to evolve, these experimental approaches will remain essential tools for rapidly assessing the pathogenic potential of emerging variants and guiding public health responses.

The formation of syncytia, or multinucleated giant cells, represents a significant pathological feature of SARS-CoV-2 infection, with considerable variation among viral variants. This phenomenon occurs when the viral spike (S) protein on infected cells interacts with receptors on neighboring cells, triggering membrane fusion and the creation of large, combined cellular structures. Emerging research indicates that syncytia formation contributes substantially to viral pathogenicity by facilitating viral spread, enabling immune evasion, and causing direct cellular damage [28] [29]. Among SARS-CoV-2 variants, the Delta variant demonstrates markedly enhanced syncytia-forming capability compared to Omicron subvariants, providing a potential explanatory factor for their differing clinical impacts. This comparative analysis examines the experimental evidence establishing syncytia formation as a key pathogenicity marker, with particular focus on Delta's superior fusion capacity across various model systems.

Quantitative Comparison of Syncytia Formation Across Variants

Variant-Specific Syncytia Formation Efficiency

Table 1: Comparative syncytia formation capabilities of SARS-CoV-2 variants

| Variant | Syncytia Formation Efficiency | Key Supporting Evidence | Experimental Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delta | High | Enhanced fusogenicity; faster fusion kinetics; larger and more numerous syncytia [30] [31] | VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells [31]; Primary airway cells [30]; First-trimester trophoblast cells [16] |

| Omicron (BA.1) | Reduced | Decreased cell-cell fusion despite efficient replication [16] [32] | hACE2 transgenic mice [32]; Primary trophoblast cells [16] |

| Omicron (BA.2, BA.5) | Intermediate | Moderate fusogenicity compared to Delta and BA.1 [16] | Primary trophoblast cells [16]; Cat lung explant cultures [33] |

| Ancestral (D614G) | Baseline | Standard fusion capability; surpassed by all Variants of Concern [30] | Multiple cell lines (Caco-2, Calu-3, Vero) [30] |

Table 2: Quantitative differences in syncytia formation and associated pathogenicity

| Variant | Relative Syncytia Size | Relative Syncytia Number | Associated Pathogenicity | Nuclear Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delta | Large [30] | Numerous [30] | High; severe lung inflammation [32] | Yes (N-protein and virions) [31] |

| Omicron BA.1 | Small [16] | Reduced [16] | Low; minimal weight loss in models [32] | Not observed [31] |

| Omicron BA.5 | Intermediate [16] | Intermediate [16] | Low to moderate [32] | Not observed [31] |

| Ancestral D614G | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline for comparison | Not specified |

Biological Consequences of Enhanced Syncytia Formation

The enhanced syncytia formation capability of the Delta variant correlates with several critical pathological outcomes:

- Prolonged viral persistence: Syncytia may serve as "viral escape rooms" that protect viral components from immune detection and clearance, potentially contributing to long COVID pathogenesis [28].

- Tissue damage and inflammation: Delta infection causes significant nuclear membrane damage and cellular destruction, features not observed with Omicron variants [31].

- Placental dysfunction: In trophoblast models, Delta infection alters syncytiotrophoblast dynamics and increases syncytial knot formation, potentially explaining adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with COVID-19 [16].

- Endothelial barrier compromise: Spike protein expression in endothelial cells induces syncytia formation with disrupted cell-cell adhesions, potentially contributing to vascular dysfunction in severe COVID-19 [34].

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Syncytia Quantification

Primary Trophoblast Cell Fusion Assay

Cell Isolation and Culture: First-trimester cytotrophoblast cells (CTBs) were isolated from human placentas (9-11 weeks gestation) following enzymatic digestion with Trypsin and separation via Percoll gradient centrifugation. CD45-negative cells were immunopurified to obtain CTBs, which were resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and gentamycin [16].

Infection and Differentiation: Cells were seeded in 96-well (1×10⁵ cells/well) or 24-well (1.5×10⁶ cells/well) plates. For syncytiotrophoblast (STB) infection assays, cells were incubated for 72 hours to allow spontaneous cell fusion before virus infection. Cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 variants (Delta, Omicron BA.1, BA.2, BA.5) at specified multiplicities of infection [16].

Fusion Quantification: Trophoblast fusion was evaluated by immunostaining and calculating the fusion index, representing the percentage of nuclei within syncytia relative to total nuclei. Parallel analysis of placental tissues from SARS-CoV-2-infected pregnancies quantified syncytial knot formation via immunohistochemistry [16].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for primary trophoblast fusion assays

Ex Vivo Lung Explant Culture Model

Tissue Preparation: Lung tissues were obtained from domestic cats deceased from non-lung-related causes. Tissues were washed with RPMI media supplemented with 2X antibiotics (Gentamicin and antimycotic) and chopped into 1 mm³ fragments using sterile curved surgical scissors on ice [33].

Infection Protocol: Explant suspensions were inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variants at an MOI of 1 using viral stocks propagated in Vero E6 cells. Cultures were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO₂, with infected explants collected at 0, 12, and 24 hours post-infection for transcriptomic analysis [33].

Transcriptomic Profiling: Comprehensive RNA sequencing was performed to identify differentially expressed genes associated with tissue damage, extracellular matrix organization, and immune responses. Hub gene networks were constructed to identify central regulators of syncytia-associated pathogenicity [33].

Endothelial Cell Syncytia Formation Assay

Adenoviral Spike Expression: Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were infected with adenovirus expressing SARS-CoV-2 D614G Spike protein variant. Control cells expressed eGFP alone [34].

Syncytia Quantification: Cells expressing 3 or more nuclei were identified as syncytia. The frequency of syncytia (percentage of syncytia per total number of cells) and size (nuclei per syncytia) were quantified at 48-72 hours post-infection [34].

Mechanical Regulation Assessment: The role of biomechanical factors was tested using:

- Pharmacological inhibitors: ML-7 (myosin light chain kinase inhibitor) and Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor)

- Substrate stiffness variation: 2 kPa vs. 64 kPa PDMS substrates

- Fluid shear stress application: 2, 6, and 12 dynes/cm² [34]

Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Delta's Enhanced Fusogenicity

Spike Protein Mutations and Fusion Regulation

The enhanced fusogenicity of the Delta variant stems from specific mutations in the spike protein that optimize receptor binding and membrane fusion:

- Enhanced ACE2 affinity: Delta spike protein displays higher binding affinity to ACE2 receptors compared to ancestral D614G, facilitating more efficient initiation of the fusion process [30].

- Optimized proteolytic processing: Delta's spike protein exhibits improved cleavage at the S1/S2 boundary and S2' site, enhancing fusogenic activation [30] [29].

- Nuclear localization: Unique among variants, Delta infection results in detection of N-protein and virions in the nucleus, associated with a G215C mutation in the nucleocapsid protein that may contribute to enhanced cellular damage [31].

Host Factor Interactions and Signaling Pathways

Table 3: Key host factors regulating SARS-CoV-2 syncytia formation

| Host Factor | Function in Syncytia Formation | Impact on Variants |

|---|---|---|

| ACE2 | Primary receptor for spike protein binding | Higher affinity for Delta spike enhances fusion initiation [30] |

| TMPRSS2 | Plasma membrane protease that primes spike protein | Augments cell-cell fusion, particularly for TMPRSS2-utilizing variants [30] [28] |

| IFITM proteins | Restrict fusion by increasing membrane rigidity | Similarly inhibitory across variants, but overcome by enhanced fusogenicity [30] [29] |

| Myosin Light Chain Kinase (MLCK) | Regulates actomyosin contractility during fusion | Critical for endothelial syncytia formation; inhibited by ML-7 [34] |

| TP53 | Modulates chromatin accessibility and cellular senescence | Differential activation by variants modifies senescence responses [35] |

Figure 2: Molecular mechanisms of enhanced syncytia formation by Delta variant

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key research reagents for studying SARS-CoV-2 syncytia formation

| Reagent/Cell Line | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells | Viral propagation and initial fusion assays | Overexpress TMPRSS2 protease, enhancing spike protein processing and cell-cell fusion [30] [31] |

| Primary first-trimester trophoblasts | Physiological placental fusion models | Spontaneously fuse with 90% efficiency within 72h; relevant for maternal-fetal transmission studies [16] |

| Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC) | Vascular syncytia formation studies | Express ACE2 and TMPRSS2; model cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 [34] |

| Ex vivo lung explant cultures | Physiologically relevant respiratory models | Maintain tissue architecture and cellular heterogeneity; bridge in vitro and in vivo findings [33] |

| ML-7 (MLCK inhibitor) | Mechanistic studies of fusion regulation | Specifically inhibits myosin light chain kinase, reducing syncytia formation in endothelial cells [34] |

| Anti-S protein mAbs | Fusion inhibition and neutralization assays | Monitor viral infection and cell-surface spike expression; quantify infected cells [30] |

The comparative analysis of syncytia formation across SARS-CoV-2 variants reveals a consistent pattern: the Delta variant possesses superior cell-cell fusion capability compared to Omicron subvariants, correlating with its enhanced pathogenicity observed in clinical settings. This enhanced fusogenicity stems from specific spike protein mutations that optimize ACE2 receptor binding and membrane fusion efficiency. The methodological approaches outlined—including primary trophoblast models, ex vivo lung explants, and endothelial cell systems—provide robust platforms for quantifying variant-specific syncytia formation and associated pathological consequences. These experimental models demonstrate that Delta's enhanced fusion activity translates to increased tissue damage, inflammatory responses, and potential for persistent infection through syncytia-mediated viral sanctuary sites. As SARS-CoV-2 continues to evolve, monitoring the syncytia-forming potential of emerging variants will remain crucial for assessing their pathogenic potential and guiding appropriate public health responses.

Advanced 3D Respiratory Models as Powerful Tools for Viral Pathogenesis Research

Human Airway Epithelial (HAE) cultures, specifically those differentiated at the air-liquid interface (ALI), have emerged as a physiologically relevant in vitro system for investigating respiratory virus pathogenesis. These cultures recapitulate the pseudostratified epithelium of the human respiratory tract, comprising ciliated cells, goblet cells, club cells, and basal cells [36] [37]. This complex cellular architecture, along with the presence of mucus and functional cilia, makes HAE cultures a superior model for studying viral tropism, replication kinetics, and host-cell interactions compared to conventional, undifferentiated cell lines [38]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, HAE cultures proved indispensable for delineating the functional differences between SARS-CoV-2 variants, particularly the highly pathogenic Delta (B.1.617.2) and the highly transmissible Omicron (B.1.1.529). This guide provides a comparative analysis of these variants using HAE models, summarizing key experimental data and methodologies to inform preclinical research and therapeutic development.

Experimental Replication and Cytopathic Effect (CPE) Profiles

A critical differentiator between SARS-CoV-2 variants is their efficiency of replication and the subsequent damage they inflict on the respiratory epithelium.

Replication Kinetics

Infection of primary nasal HAE cultures reveals distinct replication dynamics. One study found that all variants of concern (VOCs) replicated to higher titers than the ancestral strain, suggesting a selection for replication efficiency. In these upper respiratory models, Omicron reached the highest titers at early time points (24-72 hours post-infection), followed by Delta [38]. This aligns with Omicron's high transmissibility. In contrast, infections in the Calu-3 lung epithelial cell line showed that Alpha and Beta VOCs reached higher titers than Omicron, indicating that Omicron is particularly optimized for replication in the upper airway [38]. A mathematical modeling study further supported that Omicron has a significantly lower cell entry rate than Delta, which may contribute to its attenuated replication in some lower respiratory models [20].

Cytopathic Effects (CPE) and Epithelial Damage

Despite its high replicative ability in the nose, Omicron causes less severe damage to the airway epithelium. Infections with the Delta variant result in the most pronounced cytopathic effects in both primary nasal cultures and lung cell lines [38]. These effects include:

- Syncytia formation: Large, multinucleated cells formed by virus-induced cell fusion, arranged in a net-like structure [37].

- Loss of barrier integrity: A significant reduction in transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER), a key indicator of epithelial barrier function [38] [37].

- Ciliary dysfunction: Marked by cilium shrinking, beaded changes, and disordered cilia, which compromises mucociliary clearance [37].

- Apoptosis: SARS-CoV-2 infection in HAE cultures primarily induces apoptotic cell death rather than necrosis [37].

Table 1: Comparative Replication and Cytopathic Effects of SARS-CoV-2 Variants in Airway Models

| Parameter | Delta Variant | Omicron Variant | Experimental Model | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Titer (Upper Airway) | High | Highest (early time points) | Primary Nasal HAE Cultures | [38] |

| Peak Titer (Lower Airway) | High | Lower than Alpha/Beta | Calu-3 Lung Cell Line | [38] |

| Cell Entry Rate | High | Significantly Lower | Caco-2 & Calu-3 Mathematical Modeling | [20] |

| Syncytia Formation | Pronounced | Less Pronounced | Primary HAE Cultures | [38] [37] |

| Barrier Integrity Loss | Severe | Milder | Primary HAE Cultures / TEER | [38] [37] |

| Ciliary Damage | Severe (loss of beating) | Milder | Primary Nasal HAE Cultures | [38] |

| Primary Cell Death Mode | Apoptosis | Apoptosis | Primary HAE Cultures / TUNEL Assay | [37] |

Host Response and Immune Activation

The host transcriptional and immune response to infection varies significantly between variants, influencing pathogenicity.

Innate Immune and Inflammatory Signaling

A key finding is that Omicron infection induces a stronger interferon (IFN) and interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) response compared to Delta in HAE cultures [38]. This robust innate immune activation may contribute to its attenuated phenotype. In contrast, the wild-type and Delta variants trigger a more potent upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. A study in K18-hACE2 mice showed the wild-type variant induced the highest expression of cytokines like IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-17α, and IFN, as well as chemokines such as CCL4, CCL11, CXCL9, and CXCL10, particularly in the brain [21]. The Delta variant induced a similar but less intense profile, whereas the Omicron variant elicited a markedly weaker inflammatory response [21].

Immediate Early Gene Response

Unique to SARS-CoV-2 is its suppression of the host's immediate early gene (IEG) response. Transcriptomic analysis of infected HAE cultures revealed that SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and HCoV-229E infection all increase the expression of IEGs like FOS, FOSB, and NR4A1 [36]. SARS-CoV-2 uniquely lacks this induction, a signature confirmed in both experimental and clinical datasets [36]. Furthermore, interfering with NR4A1 signaling reduced replication of both SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV, suggesting IEGs play a role in coronavirus replication [36].

Apoptotic Signaling

Apoptotic pathways are also differentially activated. In mouse models, most apoptotic factors (e.g., caspase 8, caspase 9, p53, Bax) were mainly upregulated in the brain tissues of Omicron-infected mice, with minimal upregulation (less than 3-fold) in the lungs or kidneys [21]. This suggests variant- and tissue-specific regulation of cell death pathways.

The diagram below summarizes the core host signaling pathways differentially activated by SARS-CoV-2 infection in airway epithelial cells and their logical relationships.

Diagram Title: Host Signaling Pathways in SARS-CoV-2 Infected Airway Epithelium

Viral Entry and Morphogenesis

The mechanism of viral entry and the subsequent assembly and release of virions are fundamental to understanding variant-specific pathogenesis.

Viral Entry Pathways

All SARS-CoV-2 VOCs, including Omicron, primarily enter the cell via a TMPRSS2-dependent pathway [38]. This cell-surface protease cleaves the viral spike protein, facilitating direct membrane fusion. However, Omicron is more likely than other variants to use an additional endosomal route of entry [38]. This alternative pathway, which is TMPRSS2-independent and may rely on cathepsins, could partly explain Omicron's reduced efficiency in infecting TMPRSS2-high lung cells compared to Delta [38] [20].

Morphogenesis and Cell Tropism

The morphogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 in HAE cultures shares features with other coronaviruses, including the formation of double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) in the cytoplasm, which serve as sites for viral RNA synthesis [37]. Virus particles are assembled and transported in vesicles to the cell surface for release via exocytosis. A key finding is that SARS-CoV-2 infects both ciliated and secretory cells (including goblet and club cells) [37]. This broad tropism, distinct from many other human coronaviruses that preferentially infect either ciliated or secretory cells, may contribute to SARS-CoV-2's high transmissibility and pathogenicity.

Table 2: Comparative Viral Entry and Cellular Tropism of SARS-CoV-2 Variants

| Parameter | Delta Variant | Omicron Variant | Experimental Model | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Entry Route | TMPRSS2-dependent | TMPRSS2-dependent | Primary Nasal & Lung Models | [38] |

| Alternative Entry | Less Common | More Common (Endosomal) | Primary Nasal & Lung Models | [38] |

| TMPRSS2 Usage | High | Reduced | Caco-2 & Calu-3 Modeling | [20] |

| Infected Cell Types | Ciliated & Secretory | Ciliated & Secretory | Primary HAE Cultures / IF & TEM | [37] |

| Intracellular Features | Double-Membrane Vesicles (DMVs) | Double-Membrane Vesicles (DMVs) | Primary HAE Cultures / TEM | [37] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

To faithfully recapitulate the experiments cited in this guide, researchers require specific biological tools and reagents. The following table details key solutions for establishing and infecting HAE cultures.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HAE Culture Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells (PBEC) | Foundation for creating physiologically relevant, well-differentiated HAE cultures at ALI. | Cells from 4 donors used for coronavirus transcriptome analysis [36]. |

| Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) Culture System | Platform for differentiating PBECs into a pseudostratified, mucociliary epithelium that mimics the human airway. | 6-week-differentiated ALI-PBEC cultures [36]. |

| Primary Nasal Epithelial Cultures | Model specifically for upper respiratory infection, derived from patient nasal cavities. | Patient-derived primary nasal cultures grown at ALI [38]. |

| Calu-3 Cell Line | Immortalized human lung epithelial cell line used as a model for lower respiratory infection. | Used to compare variant replication in lung epithelium [38] [20]. |

| Vero E6 Cells | African green monkey kidney cell line commonly used for SARS-CoV-2 propagation and plaque assays. | Used for virus stock propagation and TCID₅₀ assays [38] [33]. |

| RT-qPCR Assays | Quantification of intracellular viral RNA copies and host gene expression. | Used to measure viral RNA and immune gene expression (e.g., TLRs, cytokines) [21] [36]. |

| SARS-CoV-2 Specific Antibodies | Detection of viral proteins (e.g., Nucleocapsid) for immunofluorescence and culture confirmation. | Antibody against SARS-CoV-2 N protein for IF microscopy [37] [39]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, below are outlines of the core methodologies derived from the cited studies.

Protocol 1: HAE Culture Infection and Viral Titration

This protocol is adapted from studies using primary HAE cultures to model SARS-CoV-2 infection [36] [38] [37].

- Culture Establishment: Plate primary human bronchial or nasal epithelial cells on transwell filters and allow them to differentiate at an air-liquid interface for 4-6 weeks to form a mature, mucociliary epithelium.

- Viral Inoculation: Apply a defined inoculum (e.g., ~30,000 PFU or MOI of 0.1) of the SARS-CoV-2 variant of interest in a small volume to the apical surface of the HAE cultures. Incubate for 1-2 hours to allow for viral adsorption.

- Sample Collection: Following incubation, wash the apical surface to remove unbound virus. At designated time points post-infection (e.g., 6, 12, 24, 48, 72 hours), collect apical wash samples by adding and retrieving a buffer solution.

- Virus Quantification:

- Infectious Titer: Determine the titer of infectious virus in apical washes using a plaque assay or the median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID₅₀) assay on permissive cells like Vero E6. Titers are expressed as Log₁₀ PFU/mL or Log₁₀ TCID₅₀/0.1 g [21] [38].

- Viral RNA: Extract RNA from apical washes or infected cells and quantify viral RNA copies via RT-qPCR targeting genes like the SARS-CoV-2 N1 gene [36] [39].

Protocol 2: Host Transcriptomic Analysis via Bulk RNA-seq

This protocol details the process for analyzing the host transcriptional response to infection, as performed in [36] and [33].

- Infection and RNA Extraction: Infect HAE cultures as described in Protocol 1. At specific time points post-infection, lyse cells directly on the transwell insert and extract total RNA.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from the extracted RNA. Perform bulk RNA-sequencing on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina) to generate transcriptome-wide data.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Differential Expression: Map sequences to the human reference genome and compare gene expression profiles between infected and mock-infected control cultures. Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) based on a false discovery rate (FDR) and fold-change threshold (e.g., FDR < 0.05, FC > 1.5) [36].

- Pathway Analysis: Subject the list of DEGs to functional enrichment analysis using databases like Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) to identify activated or suppressed signaling pathways (e.g., interferon signaling, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction) [33].

Human Airway Epithelial cultures stand as an indispensable tool for respiratory virus research, offering a physiological benchmark that simple cell lines cannot match. The experimental data generated in HAE models have been crucial for objectively comparing SARS-CoV-2 variants, revealing that the Delta variant's high pathogenicity is linked to efficient TMPRSS2-mediated entry, robust replication, and induction of severe cytopathic effects and inflammation. In contrast, the Omicron variant's phenotype is characterized by altered entry pathways, optimized upper respiratory replication, and a attenuated lower respiratory pathology, despite eliciting a stronger innate interferon response. These insights, derived from a model that faithfully recapitulates human respiratory architecture, are vital for guiding the development of future antiviral strategies and preparing for the emergence of new pathogenic respiratory viruses.

This guide objectively compares infection protocol parameters—specifically Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) optimization and sample collection timepoints—for SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variants in 3D respiratory models. The data presented supports the broader research thesis comparing the pathogenicity of these variants by detailing the experimental methodologies and reagents essential for generating comparable, reproducible results.

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs) necessitates standardized in vitro infection protocols to accurately compare viral pathogenicity and drug efficacy. Research using ex vivo human bronchus and lung cultures and human 3D airway epithelial models has revealed significant differences in how Delta and Omicron variants infect and damage respiratory tissue [40] [6]. This guide provides a direct comparison of core experimental parameters, namely MOI and sample collection timepoints, to ensure consistent and validated approaches across studies.

Quantitative Data Comparison of Variant Replication

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from foundational studies, highlighting differences in viral replication kinetics and cytopathic effects between Delta and Omicron variants. These results directly inform protocol optimization.

Table 1: Comparative Replication and Pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Variants in Respiratory Models

| Variant | Experimental Model | Key Replication Finding | Key Pathogenicity Finding | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omicron | Human bronchus ex vivo | Faster replication in bronchi at 24h/48h vs. WT & Delta (>70-fold) [6] | Reduced tissue penetration and cell damage in human airway epithelia [40] | Nature (2022) |

| Omicron | Human lung ex vivo | Significantly reduced replication vs. WT strain at 24h, 48h, and 72h [6] | Markedly smaller areas of complement activation and lower IL-6 secretion [40] | Nature (2022) |

| Delta | Human bronchus ex vivo | Significantly higher replication than WT at 72h; lower than Omicron at 24h/48h [6] | Major tissue destruction, high LDH activity, and pronounced innate immune activation [40] | Nature (2022) |

| Delta | Human lung ex vivo | No significant difference in replication vs. WT strain [6] | Readily penetrated deep into respiratory epithelium, causing major damage [40] | Nature (2022) |

| Wild-type | K18-hACE2 Mice (Lungs) | N/A | Highest expression of cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-17α, IFN, TNF) and chemokines (CCL4, CCL11, CXCL9, CXCL10) [21] | Front Biosci (2022) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Ex Vivo Human Respiratory Tissue Infection

This methodology, adapted from the Nature (2022) study, is used to compare viral replication kinetics and cellular tropism of different VOCs [6].

- Tissue Preparation: Obtain human bronchus and lung parenchyma tissues from surgical resections. Wash tissues extensively in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing antibiotics.

- Infection Process:

- Prepare virus inoculums of target VOCs (e.g., Wild-type, Delta, Omicron) in serum-free medium.

- MOI Recommendation: The study quantified input virus but often normalized by tissue weight; a common approach is to use a standardized TCID₅₀ per tissue sample (e.g., 10⁵ TCID₅₀). For cell-based assays, an MOI of 0.1-1.0 is typical for infection kinetics.

- Infect tissue explants by inoculating the apical surface for a defined period (e.g., 1 hour) at 37°C.

- Sample Collection & Viral Titration:

- Critical Timepoints: Collect tissue culture supernatants and/or tissue homogenates at 24, 48, and 72 hours post-infection (hpi).

- Titrate infectious virus using the 50% Tissue Culture Infectious Dose (TCID₅₀) assay on permissive cells like VeroE6 or Vero/TMPRSS2.

- Support with viral RNA quantification by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR).

Protocol for 3D Human Airway Epithelia Model Infection

This protocol, based on Frontiers in Immunology (2023), assesses tissue penetration, damage, and inflammatory responses [40].

- Model Preparation: Use commercially available, well-differentiated human 3D airway epithelial cultures. Maintain at an air-liquid interface (ALI) according to supplier instructions.

- Infection Process:

- Apply the virus inoculum to the apical surface.

- MOI Optimization: The study suggests that even with high inoculums, Omicron shows reduced penetration. A range of MOIs (e.g., 0.5 - 5) should be tested to ensure the model is not overwhelmed, reflecting physiological relevance.

- Sample Collection & Analysis:

- Key Timepoints: Analyze outcomes at 24-72 hpi.

- Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER): Measure at multiple timepoints to monitor real-time epithelial integrity.

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Assay: Collect basolateral medium at 48-72 hpi to quantify cell damage.

- Cytokine/Chemokine Analysis: Use basolateral medium collected at 48-72 hpi for assays like ELISA to measure IL-6 and other inflammatory markers.

- Immunofluorescence/Confocal Imaging: Fix tissues at 72 hpi to visualize viral antigen distribution, tissue architecture, and areas of immune activation (e.g., complement C3).

Viral Entry Pathway and Experimental Workflow

The differential replication of SARS-CoV-2 variants is influenced by their preferred entry pathway into host cells. The diagram below illustrates these distinct mechanisms.

Diagram 1: SARS-CoV-2 Viral Entry Pathways. Research indicates the Omicron variant shows a greater preference for the endosomal uptake pathway and increased dependence on cathepsins for entry, unlike the Delta variant, which more readily uses TMPRSS2-mediated fusion at the cell surface [6].

The following diagram outlines the core workflow for standardizing and executing infection protocols in 3D respiratory models.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for 3D Model Infection. This standardized process ensures consistent evaluation of viral replication kinetics and host responses across different SARS-CoV-2 variants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for conducting these infection studies, as cited in the referenced research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Protocol | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| VeroE6 / Vero-TMPRSS2 Cells | Permissive cell line for viral propagation and titration via TCID₅₀ assay [41] [6]. | Used for virus isolation and stock generation [42]. |

| 3D Human Airway Epithelial Models | Physiologically relevant ex vivo system for infection, assessing penetration, damage, and immunity [40]. | Model for Omicron vs. Delta tissue penetration [40]. |

| TEER Measurement System | Quantifies epithelial integrity in real-time; drop indicates barrier damage [40]. | Used to monitor epithelial health post-infection [40]. |

| LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit | Measures lactate dehydrogenase release from damaged cells, quantifying cytopathic effect [40]. | Assessed cell damage in airway epithelia [40]. |

| Cytokine Detection Assays (ELISA) | Quantifies secreted immune markers (e.g., IL-6, IL-1β) from basolateral medium [21] [40]. | Measured IL-6, IL-1β, and other cytokines in infected models [21] [40]. |

| qRT-PCR Reagents & Primers | Quantifies viral RNA copy number (e.g., targeting ORF1b, N gene) in swabs, tissue, or medium [42] [6]. | Used for viral genome quantification in swabs and tissues [42] [6]. |

| TCID₅₀ Assay Components | (Overlay medium, cell culture plates) Determines infectious viral titer in collected samples [41] [6]. | Standard method for viral titration in research [21] [6]. |

This comparison guide provides an objective analysis of experimental data and methodologies used to assess the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variants in advanced 3D respiratory models. The Omicron lineage, including subvariants like XBB.1.5, XBB.1.16, EG.5.1, and JN.1, demonstrates distinct pathogenic characteristics compared to earlier variants, with reduced lower respiratory tract pathology despite maintained or enhanced upper respiratory tract replication [43]. We synthesize findings from in vivo hamster models, ex vivo human nasal and lung epithelium, and mathematical modeling to compare viral fitness, host immune responses, and cellular damage markers. The data presented herein support the broader thesis that intra-Omicron evolution has favored upper respiratory tract fitness while attenuating severe lung disease, guiding researchers in selecting appropriate parameters and models for antiviral therapeutic development.

The emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron lineage marked a significant shift in the virus's pathogenicity. Compared to the previously dominant Delta variant, Omicron and its sub-lineages are characterized by enhanced immune evasion but attenuated severity of lower respiratory disease [43]. This change in pathogenesis necessitates a multiparametric assessment framework to quantitatively compare viral behavior. Advanced 3D respiratory models, including primary human nasal epithelial cultures at air-liquid interface (ALI) and human lung organoids, provide physiologically relevant systems for this evaluation, effectively mirroring the human respiratory tract's cellular environment and innate immune responses [43]. These models allow researchers to deconvolute the complex interplay between viral replication efficiency, cytopathic effect, and host-derived inflammatory signals, providing crucial insights for public health risk assessment and therapeutic design.

Comparative Experimental Data: Delta vs. Omicron

Viral Replication Kinetics

Table 1: Viral Replication in Respiratory Models