Harnessing Circadian Rhythms to Manage Intraindividual Variation in Immune Studies

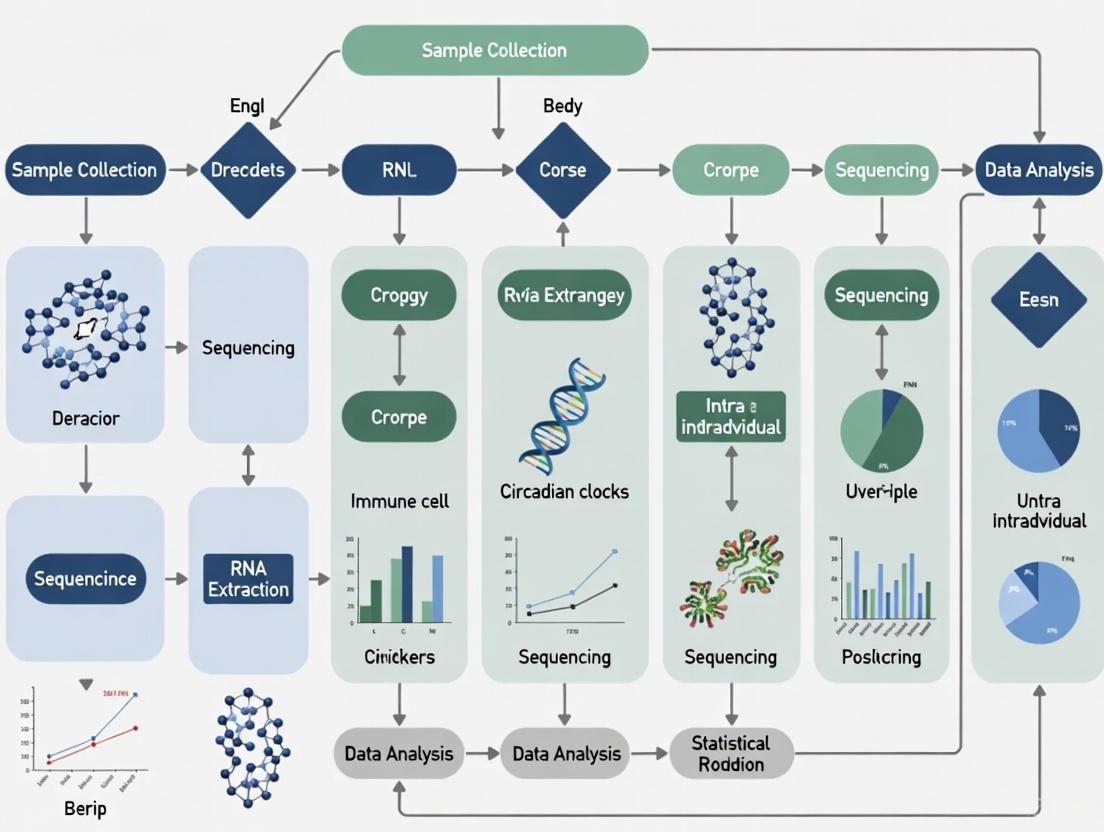

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical impact of diurnal rhythms on immune function and how to manage the resulting intraindividual variation...

Harnessing Circadian Rhythms to Manage Intraindividual Variation in Immune Studies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical impact of diurnal rhythms on immune function and how to manage the resulting intraindividual variation in biomedical studies. It explores the foundational molecular mechanisms of circadian immunity, presents methodological frameworks for integrating temporal considerations into study design, and offers troubleshooting strategies to mitigate rhythm-induced variability. Drawing on recent evidence from CAR-T cell therapy, vaccine research, and proteomics, the content synthesizes practical approaches for validating findings and optimizing therapeutic timing, ultimately aiming to enhance the precision, reproducibility, and clinical success of immunology research.

The Circadian Immune System: Unraveling Molecular Clocks and Diurnal Variation

FAQ: Core Mechanisms and Experimental Challenges

Q1: What is the core molecular mechanism of the circadian clock and how can its disruption affect immune studies? The core mechanism is a transcription-translation feedback loop (TTFL). The BMAL1/CLOCK heterodimer acts as the central activator, binding to E-box elements to drive the expression of genes including their own repressors, Period (Per) and Cryptochrome (Cry). PER and CRY proteins then form a complex that inhibits BMAL1/CLOCK activity, creating a ~24-hour oscillation cycle [1] [2]. A secondary loop involves nuclear receptors REV-ERBα and ROR, which rhythmically repress and activate Bmal1 transcription, respectively [2]. Disruption of this loop (e.g., via Bmal1 deletion) ablates circadian rhythms and leads to a hyper-inflammatory state in immune cells like macrophages, significantly increasing the production of cytokines like IL-1β [3]. This can introduce profound variability in immune outcomes based on the time of day or the genetic integrity of the clock in your model system.

Q2: Why is understanding intra-individual variation critical for diurnal rhythms research in immunology? The immune system is not static; it exhibits significant rhythmicity over the 24-hour day. Key immune parameters—such as leukocyte trafficking, cytokine release, and the response to pathogens—are all under circadian control [4]. Furthermore, an individual's immune profile is shaped by a combination of heritable and non-heritable factors, including age, sex, and environmental exposures [5] [6]. Failing to account for this temporal and individual variability can lead to inconsistent experimental results, an inability to replicate findings, and a failure to identify true biological effects. Properly managing this variation requires strict standardization of sample collection times and meticulous recording of participant metadata.

Q3: What are the practical consequences of BMAL1/CLOCK disruption in immune cell function? Disruption of the core clock, particularly loss of BMAL1, has a direct impact on immunometabolism, which in turn dictates immune cell function. In macrophages, Bmal1 deficiency causes a metabolic shift toward enhanced glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration [3]. This shift drives inflammation through two primary pathways:

- Succinate Accumulation: Increased flux through the Krebs cycle leads to accumulation of the metabolite succinate. This stabilizes the transcription factor HIF-1α, which promotes Il1b transcription [3].

- PKM2-STAT3 Signaling: BMAL1 normally represses the glycolytic enzyme PKM2. In its absence, increased PKM2 phosphorylates and activates STAT3, which further drives Il1b mRNA expression [3]. Consequently, disruption leads to a consistently heightened pro-inflammatory state.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Circadian Immunology Experiments

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| High variability in cytokine measurements | Uncontrolled diurnal rhythmicity of immune cells; circadian disruption in animal models. | Standardize time of sample collection across all experimental groups; confirm genetic background and clock gene integrity in transgenic models. | [4] [6] |

| Inconsistent immune cell population counts in flow cytometry | Circadian-driven egress of leukocytes from bone marrow and trafficking to tissues. | Process all samples at the same time of day; include time as a co-variable in statistical analysis. | [4] |

| Unstable circadian oscillations in cell culture | Desynchronization of cellular clocks in vitro; over-confluent cells. | Synchronize cells using a serum shock or dexamethasone treatment; maintain cells at sub-confluent density. | [2] |

| Loss of rhythmic gene expression in Bmal1 KO models | Complete ablation of the core feedback loop. | Use inducible or cell-specific knockout systems to study developmental vs. acute effects; validate knockout efficiency. | [1] [3] |

| Conflicting inflammatory phenotypes in different studies | Use of different global vs. cell-specific knockout models; variations in Zeitgeber Time (ZT) of analysis. | Clearly report the genetic model used and the exact ZT of all experiments and sampling. | [1] |

Table 2: Quantifying Circadian Rhythm Parameters

| Parameter | Description | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Period | The length of one complete cycle (typically ~24 hours). | Determined by tracking PER2::Luciferase bioluminescence over several days in vitro [7]. |

| Phase | The timing of a specific reference point (e.g., peak, trough) within the cycle. | Used to analyze diurnal body temperature nadir in critically ill patients vs. healthy controls [8]. |

| Amplitude | The magnitude of the difference between peak and trough of the rhythm. | Suppressed temperature rhythm amplitude indicates circadian disruption in ICU patients [8]. |

| Mesor | The rhythm-adjusted mean value around which the oscillation occurs. | CIM patients showed lower temperature rhythm mesors than non-CIM patients [8]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Circadian Rhythms in Macrophage Immune-Metabolic Function

This protocol is adapted from research investigating BMAL1's role as a metabolic sensor in macrophages [3].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cells: Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) from wild-type and Bmal1^-/-^ mice.

- Synchronization Agent: Dexamethasone (100 nM for 1 hour).

- Stimuli: Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from E. coli.

- Metabolic Inhibitors: 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, glycolysis inhibitor), Dimethyl malonate (SDH inhibitor).

- Key Assay Kits: Extracellular Flux Analyzer kit (e.g., Seahorse XF Glycolysis Stress Test), IL-1β ELISA, commercial kits for glucose uptake and lactate production.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Synchronization: Differentiate BMDMs for 6 days. Seed cells for experiments and synchronize the circadian clocks by treating with 100 nM dexamethasone for 1 hour. Replace with fresh media post-treatment.

- Stimulation: At the desired circadian timepoint (e.g., peak of inflammatory response), stimulate cells with LPS.

- Metabolic Phenotyping:

- Glycolysis: Measure the Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR) using a Seahorse XF Analyzer.

- Mitochondrial Respiration: Measure the Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) using the same instrument.

- Glucose Uptake and Lactate: Quantify using commercial colorimetric/fluorometric assays.

- Inflammatory Output Measurement:

- Harvest cell supernatant and measure IL-1β protein levels via ELISA.

- Analyze gene expression of Il1b and other targets via qPCR.

- Pathway Inhibition: Use pharmacological inhibitors (e.g., 2-DG, dimethyl malonate) to dissect the contribution of specific metabolic pathways to the inflammatory response.

Protocol 2: Pharmacological Modulation of BMAL1 with Small Molecules

This protocol utilizes the recently developed small molecule CCM to directly target BMAL1 [7].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Compound: Core Circadian Modulator (CCM), a selective ligand for the PASB domain of BMAL1.

- Cell Lines: U2OS cells or primary macrophages.

- Validational Assays: Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA), PER2::Luciferase reporter system.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Target Engagement Validation:

- Use a CETSA to confirm CCM binding to BMAL1 in a cellular context. Treat cells with CCM (EC50 ~10.3 µM), heat shock cells at a range of temperatures, and quantify the stabilization of BMAL1.

- Functional Circadian Assay:

- Treat cells carrying a PER2::Luciferase reporter with CCM.

- Monitor bioluminescence rhythms in real-time over several days. CCM treatment will produce dose-dependent alterations in the period and amplitude of PER2::Luc oscillation [7].

- Downstream Immune Phenotyping:

- Treat macrophages with CCM and assess its effect on LPS-induced inflammatory pathways, including the production of IL-1β and phagocytic activity [7].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Core Circadian Feedback Loops. This illustrates the core transcription-translation feedback loops of the molecular clock. The BMAL1/CLOCK heterodimer drives the expression of repressors (PER/CRY) and components of the stabilizing loop (REV-ERB, ROR), which together generate rhythmic gene expression [1] [2].

Diagram 2: BMAL1 Regulates IL-1β via Immunometabolism. This shows the consequences of Bmal1 deletion in macrophages. The loss of BMAL1 removes a metabolic brake, leading to enhanced glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration. This drives pro-IL-1β production via two converging pathways: PKM2-STAT3 signaling and succinate-HIF-1α stabilization [3].

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Leukocyte Migration Assay Results

| Possible Source of Error | Test or Corrective Action |

|---|---|

| Uncontrolled Circadian Timing | Standardize tissue collection and experimental procedures to a specific Zeitgeber Time (ZT), preferably during the peak migration window (e.g., ZT7 for mouse dermal dendritic cells) [9]. |

| Misaligned Animal Housing | Ensure all experimental animals are maintained under strict, synchronized 12-hour light/12-hour dark (12L:12D) cycles for at least two weeks prior to experimentation [10] [9]. |

| Neglected Chronotype (Human Studies) | In human immune cell studies, assess participant chronotype using questionnaires (e.g., Morningness-Eveningness-Questionnaire), as it can influence the diurnal rhythm of immune parameters [11]. |

| Non-Oscillating In Vitro Cells | Synchronize the intrinsic clocks of cultured immune cells (e.g., Bone Marrow-Derived Dendritic Cells) using a medium containing 50% serum ("serum shock") before conducting migration assays [9]. |

Problem: High Background in Lymphatic Vessel Staining

| Possible Source of Error | Test or Corrective Action |

|---|---|

| High Antibody Concentration | Titrate antibodies against key lymphatic markers (e.g., anti-LYVE-1) to determine the optimal concentration that minimizes non-specific binding [12]. |

| Inadequate Blocking | Implement a blocking step prior to primary antibody incubation using a solution such as 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) with 10% normal serum from the same species as the secondary antibody [12]. |

| Antigen Retrieval Issues | For fixed tissues, optimize antigen retrieval by empirically testing different treatment times or solutions to restore the immunoreactivity of antigens like CD99 and JAM-A without destroying tissue morphology [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the time of day I collect blood or tissue samples so critical in immunology research?

A: The immune system is highly rhythmic. The numbers and migratory capacities of leukocytes in the blood and tissues oscillate over 24 hours [13]. For example, inflammatory monocyte recruitment to sites of inflammation is stronger in the afternoon (ZT8 in mice) compared to the morning (ZT0) [10]. If sampling time is not controlled, it introduces significant variation, potentially obscuring true experimental effects or treatments.

Q2: My research involves human participants. How can I account for circadian rhythms?

A: Two key strategies are:

- Standardize Sampling Time: Collect all samples at the same time of day for all participants in a study to minimize variability [11].

- Assess Chronotype: Use standardized questionnaires to determine if a participant's natural sleep-wake cycle (morningness or eveningness) influences your immune readouts. One study found that the IMMAX immune age score decreased during the day in morning-type individuals [11].

Q3: Are the circadian rhythms in immune cell migration just a response to light, or are they built into the cells themselves?

A: Evidence supports both systemic and cell-intrinsic regulation. Immune cells possess their own functional molecular clocks, making their migratory capacity cell-autonomous [10] [14] [9]. This intrinsic rhythm is synchronized by the body's master clock but persists even in constant darkness or in ex vivo conditions, confirming it is a true circadian process and not just a light-driven reaction [10] [9].

Q4: What is the clinical relevance of circadian leukocyte trafficking?

A: Understanding these rhythms is paving the way for "chronotherapy." The efficacy of treatments, including vaccinations and immunotherapies like immune checkpoint blockade and CAR-T cell therapy, can be significantly influenced by the time of day they are administered [10] [14]. Furthermore, disrupted circadian rhythms are linked to exacerbated inflammation in autoimmune diseases [15] [13].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Key Experimental Workflow: Analyzing Rhythmic DC Migration

The following diagram illustrates a key method from research for studying circadian-controlled dendritic cell (DC) migration ex vivo.

Protocol Details: This method demonstrated that DC infiltration into skin lymphatics peaks during the rest phase (ZT7, "day") in mice and is controlled by rhythmic expression of adhesion molecules and chemokines in lymphatic endothelial cells [9]. The rhythm persists in constant darkness, proving it is circadian [9].

Quantifying Circadian Immune Variation

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings on the diurnal variation of different immune parameters, essential for designing and interpreting experiments.

Table 1: Measured Diurnal/Circadian Variations in Immune Parameters

| Immune Cell / Parameter | Observed Rhythm (Model) | Key Change | Potential Molecular Regulator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dermal Dendritic Cell (DC) Migration | Peaks at ZT7 (day), trough at ZT19 (night) (Mouse) [9] | Increased infiltration into lymphatics during peak [9] | CCL21, LYVE-1, CD99, JAM-A (in LECs) [9] |

| Inflammatory Monocyte Recruitment | Stronger at ZT8 vs ZT0 (Mouse) [10] | Reduced bacterial spread, stronger inflammatory response [10] | BMAL1/CLOCK binding to Ccl2 promoter [10] |

| Neutrophil Aging & Egress | Rhythmic aging and clearance (Mouse/Human) [10] [13] | BMAL1 regulates CXCL2, driving CD62L/CXCR4-dependent aging [10] [13] | CXCL2/CXCR2 axis; CXCL12/CXCR4 axis [10] [13] |

| Circulating Leukocyte Count | Peaks during rest phase (Mouse: day, Human: night) [10] | Oscillating numbers in bloodstream [10] | Glucocorticoids, sympathetic nervous activity [10] [11] |

| IMMAX Immune Age Score | Generally stable, but decreases in morning types (Human) [11] | Score influenced by chronotype over the day [11] | Individual chronotype [11] |

Signaling Pathways in Circadian Immune Trafficking

The core molecular clock and its regulation of key immune trafficking pathways are summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Circadian Trafficking Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-LYVE-1 Antibody | Labels lymphatic endothelial vessels for visualization [9]. | Immunofluorescence staining of skin explants to identify lymphatics for DC migration quantification [9]. |

| Anti-CD11c Antibody | Identifies dendritic cells (DCs) [9]. | Staining to track and quantify DC location and migration into LYVE-1+ lymphatics [9]. |

| PER2::Luciferase Reporter | Visualizes and tracks the phase of the intrinsic molecular clock in live cells [9]. | Using BMDCs from PER2-Luc mice to synchronize clocks and test cell-autonomous migration capacity [9]. |

| Zeitgeber Time (ZT) Framework | Standardized experimental time reference based on the light-dark cycle [10]. | Reporting all procedures relative to light onset (ZT0) to ensure reproducibility and cross-study comparison [10] [9]. |

| Serum Shock (50% Serum) | Synchronizes desynchronized cellular clocks in in vitro cultures [9]. | Creating a population of BMDCs with aligned circadian phases to study cell-intrinsic migration rhythms [9]. |

Core Concepts: Understanding Diurnal Rhythms in Immune Function

This section addresses fundamental questions about the impact of daily biological rhythms on immune parameters relevant to experimental research.

FAQ 1: What is the biological basis for diurnal variation in immune function?

The diurnal variations in immune function are governed by the circadian clock, an evolutionarily conserved endogenous time-keeping system. This system operates through transcription-translation feedback loops in immune cells. The core mechanism involves the heterodimerization of the transcription factors CLOCK and BMAL1, which bind to E-box elements in the promoters of clock-controlled genes (CCGs), including their own repressors, Period (PER) and Cryptochrome (CRY). As PER and CRY proteins accumulate, they inhibit CLOCK-BMAL1 activity, eventually degrading to restart the cycle. This molecular oscillator directly regulates the expression of many immune genes, leading to rhythmic changes in immune cell trafficking, cytokine production, and effector functions [16] [17].

FAQ 2: Which key immune parameters exhibit significant diurnal variation that could confound my experimental results?

Multiple immune parameters oscillate over 24 hours. The table below summarizes key oscillating immune components based on recent research:

Table 1: Diurnal Variations in Key Immune Parameters

| Immune Parameter | Observed Diurnal Variation | Peak Time (Acrophase) | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total White Blood Cells (WBCs) | Nocturnal acrophase [18] | Dark phase | Horse |

| Lymphocytes | Early morning acrophase [18] | Early morning | Horse |

| Neutrophils | Diurnal acrophase [18] | Light phase | Horse |

| CD4+ T Cells | Diurnal acrophase [18] | Light phase | Horse |

| CD8+ T Cells | Diurnal acrophase [18] | Light phase | Horse |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | Early morning acrophase [18] | Early morning | Horse |

| Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) | Diurnal acrophase [18] | Light phase | Horse |

| Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) | Nocturnal acrophase [18] | Dark phase | Horse |

| Circulating T Cells (Human) | Higher percentage in afternoon [19] | 5:00 PM (17:00) | Human |

| Circulating B Cells (Human) | Higher percentage in afternoon [19] | 5:00 PM (17:00) | Human |

| Natural Killer (NK) Cells (Human) | Higher percentage in morning [19] | 8:00 AM | Human |

These rhythms are not merely observational; they are functionally significant. For instance, the response to an immune challenge like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) varies depending on the time of day it is administered, with the intensity of the inflammatory response being time-dependent [16] [17].

Troubleshooting Guides: Managing Diurnal Variation in Your Experiments

This section provides practical solutions to common problems arising from diurnal immune variation.

Problem 1: High Unexplained Variance in Immune Cell Counts and Cytokine Measurements

Potential Cause: Blood or tissue sampling performed at inconsistent times across experimental subjects or groups, capturing different phases of the immune circadian cycle.

Solution:

- Standardize Sampling Time: Conduct all terminal and non-terminal sampling within a strictly defined and narrow time window. Consistency is more critical than the specific time chosen.

- Time-Stamp All Samples: Record the precise time of collection for every sample to enable post-hoc analysis of temporal patterns if variance persists.

- Pilot Time-Course Studies: For critical endpoints, run a small pilot study with sampling at multiple times (e.g., 4-6 time points over 24 hours) to characterize the rhythm of your specific parameter in your model system [18].

Problem 2: Inconsistent Responses to Immune Challenge or Drug Administration

Potential Cause: The intervention is being applied at different circadian times, when the immune system's baseline state and responsiveness are fundamentally different.

Solution:

- Time Interventions Chronotherapeutically: Administer immune challenges, therapeutics, or vaccines at a fixed, documented time of day for all subjects in a cohort.

- Account for Animal Housing Light Cycles: Note that for nocturnal rodents, the "active phase" (dark period) is analogous to the human day. Always report Zeitgeber Time (ZT), where ZT0 is lights-on and ZT12 is lights-off.

- Consider Reverse-Translational Timing: If a treatment is known to be more effective in humans at a certain time of day, consider aligning the timing in animal models to the corresponding phase of the activity-rest cycle [20].

Problem 3: Difficulty Reproducing Published Phenomena Involving Inflammation or Infection

Potential Cause: The original study may have inadvertently been conducted at a time of peak immune susceptibility or resistance, while your replication attempt is not.

Solution:

- Contact the Corresponding Author: Inquire about the time of day key experiments were performed.

- Review Methods Carefully: Scrutinize the original paper's methods section for mentions of a standardized light-dark cycle and time of procedures.

- Systematically Test Timing: If reproduction fails, design an experiment to test the phenomenon across multiple time points (e.g., ZT2, ZT8, ZT14, ZT20) to identify a potential time-dependent effect [16] [17].

Experimental Protocols for Diurnal Immune Studies

Protocol 1: Assessing Diurnal Variation in Circulating Leukocyte Subpopulations

This protocol is adapted from studies in horses and humans, demonstrating conservation across species [18] [19].

Workflow Diagram: Diurnal Leukocyte Analysis

Materials:

- Research-Grade Flow Cytometer: For high-throughput, multi-parameter immunophenotyping.

- Antibody Panels: Specifically designed for identifying leukocyte subpopulations (e.g., anti-CD45 for total leukocytes, anti-CD3 for T cells, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD19 for B cells, anti-CD56/16 for NK cells) [19].

- Microvette Tubes (K3 EDTA): For consistent finger-prick or venous blood collection.

- COSINOR Analysis Software: Specialized software or R packages (e.g., 'cosinor', 'circacompare') to statistically validate rhythms and determine acrophase (peak time) and robustness.

Procedure:

- Subject Acclimatization: House subjects under controlled light-dark (LD) conditions (e.g., 12h:12h) for a minimum of two weeks prior to experimentation to entrain circadian clocks.

- Sampling Schedule: Establish a 24-hour sampling schedule with collections at least every 4-6 hours. For mice, sample at ZT2, ZT6, ZT10, ZT14, ZT18, and ZT22 to cover both rest and active phases.

- Blood Collection: Collect blood via a consistent method (venipuncture, tail vein, or cardiac puncture at termination). For repeated sampling in larger animals or humans, an indwelling catheter can minimize stress.

- Cell Staining & Analysis: Process blood samples immediately. Use red blood cell lysis, followed by staining with fluorescently conjugated antibodies according to manufacturer protocols. Analyze using flow cytometry.

- Statistical Analysis: Use COSINOR or similar rhythmometric analyses to fit a cosine curve to the time-series data and determine if a significant rhythm is present.

Protocol 2: Measuring Diurnal Cytokine Production

This protocol outlines methods to track rhythmic cytokine secretion, a key effector function.

Workflow Diagram: Cytokine Rhythm Profiling

Materials:

- ELISA Kits or Multiplex Immunoassay Panels: For specific cytokines of interest (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10). Multiplex panels are efficient for measuring multiple analytes simultaneously from a small sample volume [18] [21].

- Cell Stimulation Cocktails: Such as Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for innate immune activation or PMA/Ionomycin for T cell activation.

- Microplate Reader: For quantifying ELISA results.

Procedure:

- In Vivo Cytokine Measurement: Collect plasma or serum at multiple time points across the 24-hour cycle. Store samples at -80°C until batch analysis to avoid inter-assay variability. Analyze all samples from a single subject in the same assay run.

- Ex Vivo Cytokine Production Capacity:

- Isolate primary immune cells (e.g., PBMCs, splenocytes, peritoneal macrophages) at different times of day.

- Culture a standardized number of cells with or without a potent stimulus like LPS for a defined period (e.g., 4-24 hours).

- Collect the cell culture supernatant and measure cytokine levels using ELISA or a multiplex assay.

- This method disentangles the intrinsic rhythmic capacity of cells to produce cytokines from the rhythmic systemic environment.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Diurnal Immune Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polychromatic Flow Cytometry Antibody Panels | Immunophenotyping of leukocyte subpopulations from small blood volumes (as low as 25µL) [19]. | Validate antibodies for your specific species. Panel design should minimize spectral overlap. |

| ELISA & Multiplex Bead-Based Assays | Quantification of cytokine concentrations in serum, plasma, and cell culture supernatants [18] [21]. | Multiplex assays conserve precious sample. Ensure dynamic range covers expected values. |

| COSINOR Analysis Software | Statistical package for identifying and characterizing circadian rhythms in time-series data [18]. | Available in R (cosinor2), Python, and dedicated Circadian software suites. |

| Telemetric Temperature Sensors | Continuous, stress-free monitoring of core body temperature as a robust marker of circadian phase [21]. | Validates that experimental manipulations do not disrupt overall circadian physiology. |

| REV-ERB Agonists (e.g., SR9009) / ROR Antagonists | Pharmacological tools to directly target and manipulate the molecular clockwork in vivo or in vitro [16] [20]. | Used to probe causal relationships between the clock and immune functions. |

| LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) | Standardized innate immune challenge to probe time-of-day-dependent inflammatory responses [16] [17]. | Dose and source (e.g., E. coli) must be consistent across all experiments. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Diurnal Rhythm Experiments

| Problem Scenario | Potential Underlying Mechanism | Verification Method & Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in lymphocyte counts between samples taken at the same nominal time. | Poorly controlled intraindividual variation due to inconsistent participant sampling times or preparation [19]. | - Verification: Audit sample collection logs.- Corrective Action: Strictly enforce consistent sample collection times (e.g., 8 AM ±15 min) and standardize participant pre-test conditions (fasting, activity). |

| Failure to detect expected diurnal variation in immune cell populations. | - Weak zeitgeber intensity or consistency [22] [23].- Phase misalignment between competing zeitgebers (e.g., light vs. feeding) desynchronizing peripheral clocks [22]. | - Verification: Review participant logs for light exposure and meal timing.- Corrective Action: Implement controlled, time-restricted feeding protocols and instruct participants on consistent light/dark exposure. |

| Inconsistent results from low-volume blood sampling (e.g., finger-prick). | - Technical error in small-volume processing [19].- Local blood flow factors affecting cell concentration. | - Verification: Re-train personnel on the adapted, low-volume protocol [19].- Corrective Action: Apply warm water to fingertips before collection to standardize blood flow [19]. |

| Conflicting entrainment signals in in vitro or animal models. | Peripheral immune cell rhythms are entrained by feeding, not light, creating conflict if cues are misaligned [22]. | - Verification: Check the phase relationship between light/dark and feeding/fasting cycles in the model.- Corrective Action: Align feeding time with the active phase for the model organism to ensure zeitgeber synergy [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the timing of blood collection so critical in immune studies? The prevalence of circulating immune cells, such as T helper cells and B cells, demonstrates significant diurnal variation. For example, one study found TH cells and B cells showed significantly higher percentages at 5 PM compared to 8 AM [19]. Collecting samples at inconsistent times introduces substantial intraindividual variation, obscuring true biological signals or treatment effects.

Q2: Can I use small-volume blood collection methods, like finger-pricks, for diurnal variation research? Yes. Recent research demonstrates that diurnal variations in lymphocyte prevalence can be reliably detected using small-volume (e.g., 25 µL) finger-prick blood samples, which is a less invasive alternative to traditional venipuncture [19].

Q3: What is the most potent environmental cue for synchronizing the immune system? While light is the primary zeitgeber for the central clock in the brain, feeding/fasting cycles are a more potent synchronizer for peripheral clocks, including those in metabolic organs and likely immune cells [22] [23]. The timing of food intake can entrain these clocks independent of the light cycle.

Q4: What does "phase misalignment" mean, and why is it problematic? Phase misalignment occurs when two major zeitgebers, like the light/dark cycle and feeding/fasting cycle, are out of sync (e.g., eating late at night). This conflict sends conflicting signals to the body's circadian network, which can disrupt robust circadian oscillations in peripheral tissues, including metabolic and immune functions, and is linked to physiological abnormalities [22].

Q5: Which molecular pathways integrate metabolic state with circadian rhythmicity? The nutrient-sensing enzyme Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) serves as a key integrator. Its activity is regulated by NAD+ levels, which oscillate with feeding rhythms. SIRT1, in turn, influences the core clock machinery (CLOCK/BMAL1 and PER/CRY complexes) through enzymatic activities, thereby translating metabolic state into circadian timing information in peripheral cells [22].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Assessing Diurnal Lymphocyte Variation via Low-Volume Blood Sampling

This protocol is adapted for detecting diurnal changes in lymphocyte subsets using finger-prick blood, minimizing participant burden for repeated sampling [19].

1. Participant Preparation & Sampling:

- Recruitment: Recruit healthy volunteers. (Note: The cited study used 8 participants aged 18-25 [19]).

- Sampling Times: Collect blood at two distinct time points on the same day (e.g., 8 AM and 5 PM) [19].

- Standardization: Do not require fasting, but standardize other factors like physical activity before sampling.

- Collection: Apply warm water to fingertips to increase blood flow and allow to dry. Collect a minimum of 225 µL of finger-prick blood using safety lancets into K3 EDTA Microvette tubes [19].

2. Staining & Preparation for Flow Cytometry:

- Reagents: Use a commercial lymphocyte kit (e.g., IMK Simultest: Lymphocyte Kit).

- Low-Volume Adaptation: Scale down reagent volumes to match the reduced blood volume. For a 25 µL blood sample, add 5 µL of the relevant antibody reagent [19].

- Incubation: Stain for 20 minutes at room temperature in the dark.

- Lysis: Lyse red blood cells using 500 µL of lysing solution for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash: Centrifuge (200g, 4°C), discard supernatant, and wash the cell pellet with 500 µL of PBS. Repeat centrifugation and resuspend in an appropriate buffer (e.g., 125 µL of PBS with 2% FBS and 0.1% sodium azide) [19].

3. Flow Cytometry & Analysis:

- Equipment: Use a flow cytometer (e.g., BD FACSVerse).

- Gating Strategy: Analyze using flow cytometry software (e.g., FlowJo v10.8.1). The sequential gating strategy is:

- Lymphocyte Gate: On FSC-A/SSC-A plot.

- Live Cell Gate: Using a live/dead stain (e.g., propidium iodide) on FSC-A/PerCp-Cy5.5 plot.

- Singlet Gate: FSC-H/FSC-W and SSC-H/SSC-W to exclude doublets.

- Cell Subtype Analysis: Use FITC/PE quadrants to identify specific surface markers (CD3, CD19, CD4, CD8, CD16/CD56) for T cells, B cells, helper T cells, cytotoxic T cells, and NK cells [19].

- Statistics: Use a paired, two-tailed t-test to compare morning and afternoon cell prevalence, with a p-value of less than .05 considered significant [19].

Protocol Synopsis: Mathematical Modeling of Light-Feeding Entrainment

For theoretical research, a semimechanistic mathematical model can be employed to study the convoluted effects of light and feeding cues.

- Model Structure: A two-compartment model (central and peripheral) where the central compartment processes light/dark and feeding inputs. The peripheral compartment represents a human hepatocyte, containing the core clock machinery (CLOCK/BMAL1, PER/CRY feedback loops) and the NAD+ salvage pathway influencing SIRT1 activity [22].

- Key Inputs: The model simulates different light-feeding phase relations and intensities [22].

- Key Outputs: The model predicts dynamics of peripheral clock genes and metabolic enzymes, showing that peripheral clocks can entrain completely to feeding rhythms and that the light-feeding phase relationship is critical for robust oscillations [22].

Signaling Pathway & Experimental Workflow Visualizations

Signaling Pathway of Entrainment Cues on Peripheral Immunity

Low-Volume Blood Sampling Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Diurnal Immune Cell Research

| Item | Function & Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Safety Lancets & Microvette Tubes | Enables consistent, low-volume blood collection via finger-prick, reducing participant burden and facilitating frequent sampling [19]. | Safety lancets; K3 EDTA 200 µL Microvette tubes (Sarstedt Group) [19]. |

| Polychromatic Flow Cytometry Kit | Allows for the simultaneous identification and quantification of multiple lymphocyte subsets from a single small sample. | IMK Simultest: Lymphocyte Kit (Becton Dickinson). Contains antibodies for CD3, CD19, CD4, CD8, CD16, CD56 [19]. |

| Flow Cytometer & Analysis Software | Instrument and software platform for acquiring and analyzing the stained cell samples to determine cell population percentages. | BD FACSVerse cytometer (Becton Dickinson) with FlowJo v10.8.1 software [19]. |

| Red Blood Cell Lysing Solution | Prepares whole blood for flow cytometry by removing red blood cells, which would otherwise interfere with the analysis of white blood cells. | 10x red blood cell lysing solution (e.g., BD Pharm Lyse) [19]. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | A fluorescent DNA dye used as a viability stain. PI is excluded by live cells with intact membranes; thus, PI-positive cells are dead and can be gated out. | Propidium iodide solution [19]. |

A critical, yet often overlooked, variable in biomedical research is the fundamental discrepancy between the nocturnal nature of common laboratory rodents and the diurnal nature of human physiology. This discordance can significantly impact the interpretation and translation of research findings, particularly in immunology and physiology. Research indicates that failing to account for this can hamper reproducibility, reliability, and validity in experimental data [24] [25]. This guide provides troubleshooting advice and protocols to help researchers manage intraindividual variation and effectively navigate the challenges of translating data from nocturnal mice to diurnal humans.

Troubleshooting Common Circadian Translation Issues

FAQ 1: Why does the time of day for testing rodents matter if my lab operates on a standard 9-to-5 schedule?

Testing nocturnal animals during the day (their rest phase) is akin to waking a human in the middle of the night to perform a complex task. Physiological parameters, including immune responses, core body temperature, and hormone levels, exhibit strong daily fluctuations [21] [25]. Conducting tests during the animal's inactive phase may not capture their peak functional capacity and can introduce significant variability, potentially leading to a "floor effect" where true biological differences are masked [25].

FAQ 2: How can I account for circadian rhythms without running my experiments at night?

The most effective method is to reverse the light/dark (LD) cycle of your animal housing facility. House the animals in total darkness during the day and turn on the lights at night. This allows researchers to observe and test the animals during their active phase under simulated "nighttime" conditions during standard work hours [24]. When animals need to be checked during the subjective night, use dim red lighting, as rodents cannot see red light, which prevents disruption of their circadian rhythms [24].

FAQ 3: Our immune cell counts are highly variable between replicates. Could time of day be a factor?

Yes, absolutely. Numerous immune cell populations and inflammatory markers display robust circadian rhythms. For example, in humans, total white blood cells (WBC), neutrophils, and lymphocytes show higher circulating numbers in the afternoon compared to the morning [21]. Similar rhythms are present in rodents but are phase-shifted due to their nocturnal nature. Consistent timing for sample collection is crucial for reducing this source of intraindividual variability.

FAQ 4: We are developing a drug targeting an inflammatory pathway. How relevant is circadian timing for therapy?

Circadian rhythms regulate the core inflammatory machinery, including cytokine secretion and immune cell trafficking [15] [20]. The severity of inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis often follows a daily pattern, with symptoms like morning stiffness linked to elevated nighttime levels of pro-inflammatory factors [15]. Therefore, administering therapeutics in a time-sensitive manner (chronotherapy) can optimize efficacy and minimize side effects [15].

Key Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol for Assessing Immune Cell Diurnal Variation

The following protocol, adapted from a 2023 study, demonstrates how to detect diurnal variations in lymphocyte prevalence using small-volume blood samples, relevant for both rodent and human studies [19].

- Objective: To determine diurnal variations in peripheral lymphocyte prevalence.

- Sample Collection:

- Subjects: 8 healthy volunteers (or rodents, with appropriate ethical approval).

- Timing: Collect samples at two distinct time points (e.g., 8 AM and 5 PM).

- Volume & Method: Collect a minimum of 225 µL of finger-prick blood (for humans) or tail-nick blood (for rodents) into K3 EDTA tubes.

- Staining & Analysis:

- Use a polychromatic flow cytometry kit (e.g., IMK Simultest: Lymphocyte Kit).

- Adapt reagent volumes for low blood volume (e.g., 25 µL blood + 5 µL reagent).

- Stain with conjugate antibodies for 20 minutes at room temperature.

- Lyse red blood cells for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash with PBS, centrifuge, and resuspend the pellet for analysis.

- Data Acquisition: Analyze samples on a flow cytometer (e.g., BD FACSVerse).

- Use forward scatter/side scatter to gate on lymphocytes.

- Use live/dead cell staining and singlet gating to ensure analysis of viable, single cells.

- Statistical Analysis: Use a paired Student's two-tailed t-test to compare lymphocyte counts between morning and afternoon samples. A p-value of less than .05 is considered significant [19].

Protocol for Reversed Light/Dark Cycle Housing

Implementing this protocol is fundamental for ensuring rodent data is collected during the appropriate biological time.

- Objective: To house nocturnal rodents on a reversed LD cycle to facilitate daytime testing during their active phase.

- Housing Conditions:

- Maintain the animal room in complete darkness during the human daytime (e.g., 7 AM to 7 PM).

- Switch on the lights during the human nighttime (e.g., 7 PM to 7 AM).

- Procedural Lighting:

- All procedures conducted during the dark (active) phase must be performed under safe lighting.

- Use a miner's light with a red bulb or night-vision goggles when working in the animal room during the subjective night [24].

- Tint room windows with a red film to prevent external light leaks.

- Acclimatization: Allow animals to acclimate to the reversed LD cycle for a minimum of two weeks before initiating any experiments.

- Reporting: When publishing, provide a detailed description of the LD cycle and all measures taken to protect the animals' circadian rhythms during testing [24] [25].

Circadian Regulation of Immunity: Key Data and Pathways

Diurnal Variation in Human Immune Cells and Markers

The table below summarizes the diurnal variations observed in key immune parameters in humans, highlighting the importance of consistent timing for sample collection [21].

| Immune Parameter | Direction of Change | Peak Time (Example) | Notes / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Body Temperature | Increase | Afternoon (18:00 hs) | More pronounced response to exercise in the morning. |

| Total White Blood Cells (WBC) | Increase | Afternoon (18:00 hs) | Significantly higher concentration post-exercise in the evening. |

| Neutrophils | Increase | Afternoon (18:00 hs) | Higher concentration post-exercise in the evening. |

| Lymphocytes | Increase | Afternoon (18:00 hs) | Higher concentration post-exercise in the evening. |

| IL-6 | Phase response | More pronounced at 18:00 hs | Inflammatory cytokine shows a more pronounced response to stress in the evening. |

| HSP70 | Phase response | More pronounced at 18:00 hs | Heat shock protein response is more pronounced in the evening. |

| TH Cells, B Cells | Increase | Evening (vs. Morning) | Significantly higher percentages found at 5 PM [19]. |

| NK Cells | Decrease | Evening (vs. Morning) | Significantly higher percentage in the morning [19]. |

| Cortisol | Fluctuation | Peaks around 8 AM | Levels rise in the early morning and have a nadir around noon [15]. |

Core Circadian Clock Signaling Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the core transcriptional-translational feedback loop of the mammalian circadian clock, which governs daily rhythms in physiology and immunity [26] [15] [20].

Circadian-Immune System Crosstalk

This diagram outlines the pathway by which environmental light synchronizes the central clock, which in turn regulates rhythmic immune functions, a key consideration for translational research [26] [15] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists essential reagents and materials used in the featured protocols for circadian immune research.

| Item Name | Function / Specificity | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Polychromatic Flow Cytometry Kit (e.g., IMK Simultest) | Simultaneous detection of multiple lymphocyte subsets (T, B, NK cells) via conjugated antibodies [19]. | Phenotyping immune cell subsets in small-volume blood samples over the diurnal cycle [19]. |

| Safety Lancets & Microvette Tubes (K3 EDTA) | Minimally invasive collection of small, precise volumes of peripheral blood. | Repeated sampling from the same subject (e.g., finger-prick in humans) at multiple time points to track diurnal variation [19]. |

| Telemetric Temperature Sensors | Continuous, remote monitoring of core body temperature (e.g., gastrointestinal). | Tracking the circadian rhythm of core body temperature as a physiological marker in unrestrained animals or humans [21]. |

| Red Light Bulbs / Miner's Lights | Provides illumination that is invisible to rodents, preventing circadian rhythm disruption. | Performing animal husbandry, health checks, or experimental procedures during the dark/active phase of a reversed LD cycle [24]. |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits | Quantitative measurement of specific proteins (e.g., cytokines, hormones). | Assessing diurnal levels of inflammatory markers like IL-6 or hormones like melatonin or cortisol in serum/plasma [21]. |

| Reverse Light/Dark Cycle Chamber | Environmental chamber programmed to provide a reversed 12h:12h light/dark cycle. | Housing nocturnal rodents to shift their active phase to coincide with researcher working hours for behavioral and physiological tests [24] [25]. |

Implementing Chrono-Methodologies: Practical Frameworks for Temporal Study Design

In immune studies, the biological clock is a fundamental but often overlooked variable. A growing body of evidence reveals that immune cell populations and their functions exhibit significant diurnal fluctuations. For researchers in immunology and drug development, failing to standardize sampling times introduces substantial pre-analytical variability that can obscure true experimental effects, compromise data reproducibility, and lead to erroneous conclusions. This technical support resource provides evidence-based protocols and troubleshooting guidance for managing intraindividual variation driven by circadian rhythms, enabling more robust and reliable immune monitoring in research and clinical applications.

FAQs: Addressing Key Concerns in Diurnal Immune Research

1. Why is standardizing sampling time particularly critical for immune cell analysis?

Circulating immune cell populations demonstrate predictable diurnal variations. For instance, T-helper (TH) cells and B cells show significantly higher percentages in the afternoon (e.g., 5 PM) compared to morning samples (e.g., 8 AM), whereas Natural Killer (NK) cells demonstrate a significantly higher morning prevalence [19]. These endogenous rhythms mean that sampling at inconsistent times of day confounds experimental results by introducing systematic biological noise that is unrelated to the experimental intervention or condition being studied.

2. Can I use small-volume blood samples, like finger-prick collections, to reliably study these diurnal variations?

Yes, recent research confirms that small-volume finger-prick blood samples (e.g., 25 µL) are sufficient to detect significant diurnal variations in lymphocyte subsets using modern analytical platforms like flow cytometry [19]. This validates a less invasive sampling method that can improve participant acceptability and facilitate more frequent time-point collections in longitudinal studies.

3. Beyond immune cells, what other pre-analytical factors should I control for in my study design?

The pre-analytical phase encompasses all steps from sample collection to analysis, each being a potential source of variability. Key factors include [27]:

- Circadian Rhythm and Nutritional Status: Metabolite levels and physiological states fluctuate with time of day and food intake.

- Sample Collection Materials: Additives in collection tubes (e.g., anticoagulants like EDTA, heparin, or citrate) and components like separator gels can leach chemicals and alter metabolomic and lipidomic profiles.

- Sample Processing and Storage: Variations in clotting time (for serum), centrifugation speed, temperature, freeze-thaw cycles, and storage duration can significantly impact analyte stability.

Consistent standardization of these factors across all samples is paramount for data integrity.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Source | Recommended Test or Action |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Noise | Insufficient washing steps during assay procedures. | Increase number of washes; add a 30-second soak step between washes [28]. |

| Poor Duplicates (High variability between technical replicates) | Insufficient or uneven washing; uneven plate coating; reused plate sealers. | Check automatic plate washer ports for obstructions; ensure consistent coating volumes and methods; use fresh plate sealers for each step [28]. |

| Poor Assay-to-Assay Reproducibility | Variations in incubation temperature or protocol; improper calculation of standard curves. | Adhere strictly to recommended incubation temperatures and a consistent protocol; check calculations and use internal controls [28]. |

| Inconsistent Diurnal Data | Non-standardized sampling times; unaccounted for participant activities (meals, exercise). | Collect all samples within a narrow, consistent time window for each participant; record and control for fasting status and physical activity [27] [19]. |

| Unexpected Immune Cell Counts | Contamination of samples; incorrect handling or delays in processing. | Use fresh reagents and buffers; ensure samples are processed immediately according to a standardized protocol [27] [28]. |

Experimental Protocols: A Methodology for Diurnal Variation Assessment

The following protocol, adapted from contemporary research, demonstrates a methodology for detecting diurnal lymphocyte variation using small-volume blood samples [19].

Objective

To assess diurnal variations in peripheral lymphocyte prevalence using finger-prick blood samples and flow cytometry.

Materials and Reagents

- Safety lancets

- K3 EDTA Microvette tubes (e.g., Sarstedt Group)

- Polychromatic antibody kit for lymphocyte immunophenotyping (e.g., IMK Simultest: Lymphocyte Kit)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Red blood cell lysing solution

- Flow cytometer with appropriate configuration

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Participant Preparation and Sampling: Recruit participants and obtain informed consent. Collect a minimum of 225 µL of finger-prick blood using safety lancets into K3 EDTA tubes at two distinct time points (e.g., 8 AM and 5 PM) on the same day. Apply warm water to fingertips to increase blood flow prior to collection.

- Staining: Pipette 25 µL of blood into a test tube. Add 5 µL of the appropriate antibody reagent (volumes may be scaled down from manufacturer's instructions). Mix gently and incubate for 20 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

- Lysis and Washing: Add 500 µL of 10x red blood cell lysing solution to the tube. Vortex and incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature. Centrifuge at 200g for 5 minutes at 4°C and carefully discard the supernatant. Wash the cell pellet with 500 µL of PBS, centrifuge again, and discard the supernatant.

- Resuspension and Analysis: Resuspend the final cell pellet in an appropriate stabilization buffer (e.g., 125 µL of PBS with 2% FBS). Analyze the samples immediately on a flow cytometer.

- Data Analysis: Use flow cytometry analysis software (e.g., FlowJo) for gating and compensation. Identify lymphocyte populations via forward-scatter/side-scatter gating, followed by live/dead cell and singlet gating. Use fluorescence parameters to distinguish specific cell types (T cells, B cells, NK cells, etc.). Employ paired statistical tests (e.g., paired two-tailed t-test) to compare cell prevalence between morning and afternoon samples.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram: Pre-analytical Workflow for Immune Cell Diurnal Studies

Diagram: Circadian-Immune Signaling Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| K3 EDTA Microvette Tubes | For consistent and precise collection of small-volume finger-prick blood samples; EDTA prevents coagulation by chelating calcium [19]. |

| Polychromatic Antibody Panels | Pre-configured antibody kits for immunophenotyping (e.g., identifying T cells, B cells, NK cells) via flow cytometry, enabling comprehensive immune profiling from small samples [19]. |

| Safety Lancets | Enable standardized, minimally invasive capillary blood collection from fingertips, improving participant comfort and facilitating repeated sampling [19]. |

| Red Blood Cell (RBC) Lysing Solution | Lyses red blood cells in whole blood samples without damaging white blood cells (lymphocytes, monocytes, granulocytes), which is a critical sample preparation step for flow cytometric analysis of immune cells [19]. |

| Standardized Collection Tubes | Using the same type and manufacturer of blood collection tubes for an entire study is crucial, as tube additives (e.g., heparin, EDTA, citrate) and separator gels can leach chemicals and variably affect subsequent analytical results [27]. |

Chronovaccination is an emerging field that investigates how the timing of vaccine administration, in alignment with the body's innate 24-hour circadian rhythms, can be used to optimize immunogenicity and effectiveness. This approach represents a low-risk, cost-effective strategy to enhance vaccine-induced protection, which is particularly relevant for higher-risk populations, such as the elderly, who often develop less robust immune responses. This technical support center provides a foundational framework for researchers designing and troubleshooting experiments in this field, with a focus on managing the intraindividual variation inherent in diurnal rhythms research.

FAQs: Core Concepts in Chronovaccination

1. What is the fundamental premise behind chronovaccination? The immune system exhibits strong circadian rhythms, with oscillations observed in cytokine responses, circulating leukocyte counts, and the activity of both innate and adaptive immune cells. These rhythms are controlled by cell-intrinsic circadian clocks. The core premise of chronovaccination is that aligning the time of vaccine administration with peaks in immune cell function and trafficking can enhance the subsequent immune response [29] [30].

2. What is the clinical evidence supporting time-of-day effects on vaccine efficacy? A 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis identified 17 studies investigating vaccination timing for COVID-19, influenza, hepatitis B, hepatitis A, and pneumococcal infection. Eleven of these studies demonstrated statistically significant effects of timing on antibody response, with 10 reporting stronger responses after morning vaccination. The meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) confirmed that morning influenza vaccination elicited a significantly stronger antibody response than afternoon vaccination, with a larger effect size observed in adults aged 65 and older [29] [31].

3. Which populations show the most pronounced benefit from morning vaccination? Current evidence suggests that older adults (aged 60 and above) derive the most consistent benefit from morning vaccination. In the systematic review, five out of six subgroups with an average age of 60+ showed significantly stronger antibody responses following morning vaccination [29]. The effect appears to be more variable and less pronounced in younger populations [31].

4. Are time-of-day effects consistent across all vaccine types? While the principle may be universal, the magnitude of the effect appears to vary. The most robust evidence from RCTs currently exists for influenza and COVID-19 vaccines, as well as the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. For instance, one study found that morning BCG vaccination led to stronger antigen-specific IFN-γ production and trained innate immunity compared to evening vaccination [30]. More research is needed to characterize effects across a wider range of vaccine platforms.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Issue 1: Inconsistent or Non-Significant Time-of-Day Effects in Study Data

- Potential Cause: Inadequate control for confounding variables that interact with circadian rhythms, such as participant age, sex, or chronotype (an individual's natural inclination for morning or evening activity).

- Solutions:

- Stratify Recruitment and Randomization: Ensure age and sex are evenly distributed between your morning and afternoon vaccination groups. Consider using chronotype questionnaires to account for this variable.

- Standardize Sample Collection: If collecting longitudinal blood samples for immune monitoring, strictly standardize the time of day for each draw for all participants to avoid confounding by diurnal immune variation.

- Refer to Existing Data: Consult the summary tables below to benchmark your effect sizes against published findings. A lack of effect in a young cohort may be an expected finding.

Issue 2: High Variability in Immune Readouts Within Time Groups

- Potential Cause: High intraindividual variation driven by unmeasured lifestyle factors or imprecise laboratory protocols.

- Solutions:

- Control Pre-Vaccination Activity: Where possible, advise participants to avoid strenuous exercise, significant sleep deprivation, or alcohol consumption in the 24 hours preceding vaccination, as these can independently modulate immune function.

- Standardize Laboratory Assays: Use controlled, validated protocols for processing blood samples and conducting immunoassays. Evidence shows that even small-volume finger-prick blood samples can reliably detect diurnal variations in lymphocyte subsets, offering a less invasive method for repeated measures [19].

Issue 3: Determining the Optimal "Morning" and "Afternoon" Time Windows

- Guidance: Based on successful RCTs, a common and methodologically sound approach is to define "morning" as 9:00 AM – 11:00 AM and "afternoon" as 3:00 PM – 5:00 PM [29] [30]. Adhering to these defined windows, rather than a broad "AM/PM" classification, improves experimental consistency and the ability to compare results across studies.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent meta-analyses and studies for easy reference.

Table 1: Summary of Time-of-Day Effects on Antibody Response from a 2025 Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis [29] [31]

| Vaccine Type | Number of Studies | Studies Showing Significant Effect | Direction of Significant Effect | Key Subgroup Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza | 5 | 2 out of 2 RCTs | Morning > Afternoon | Effect strongest in adults ≥65 years. |

| COVID-19 | 9 | Multiple observational studies | Morning > Afternoon | Improved B-cell and Tfh responses with morning vaccination. |

| Others (Hep A/B, Pneumo) | 3 | Varied | Primarily Morning > Afternoon | More data required for conclusive patterns. |

Table 2: Meta-Analysis Results for Influenza Vaccination by Age Group [29] [31]

| Age Group | Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) | 95% Confidence Interval | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Ages | 0.24 | 0.01 – 0.47 | p < 0.05 |

| Adults ≥65 years | 0.32 | 0.21 – 0.43 | p < 0.001 |

| Adults ≤60 years | 0.00 | -0.17 – 0.17 | Not Significant |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Randomized Controlled Trial for Chronovaccination

This protocol is adapted from the RCTs conducted by Long et al. (2016) and Liu et al. (2022) [29].

- 1. Participant Recruitment:

- Target Population: Define your cohort (e.g., healthy adults ≥65 years). Exclusion Criteria: Immunocompromised state, recent infections, use of immunosuppressant drugs, unstable sleep-wake cycles.

- Stratification: Stratify by sex and age to ensure balanced allocation.

- 2. Randomization & Blinding:

- Randomly assign participants to morning (9:00-11:00) or afternoon (15:00-17:00) vaccination groups. The vaccinator should be blinded to the group assignment where possible.

- 3. Vaccination:

- Administer the standard vaccine (e.g., inactivated influenza vaccine) according to the assigned time window.

- 4. Sample Collection for Immune Monitoring:

- Collect blood samples at baseline (pre-vaccination) and at defined endpoints post-vaccination (e.g., 4 weeks for antibody titers).

- Crucially, all follow-up samples for a given participant should be drawn at the same time of day as their vaccination to control for diurnal variation in immune markers.

- 5. Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Antigen-specific IgG antibody titers, measured via ELISA.

- Secondary: Seroconversion rates, T-cell responses (e.g., ELISpot for IFN-γ), and innate immune parameters.

The workflow for this experimental design is outlined below.

Protocol 2: Assessing Diurnal Immune Variation in Human Blood

This protocol details a method for detecting diurnal changes in lymphocyte populations, adapted from a 2023 study that validated the use of small-volume blood samples [19].

- 1. Participant Preparation:

- Recruit healthy volunteers. Standardize the day prior to sampling (avoid strenuous exercise, alcohol).

- 2. Serial Blood Sampling:

- Collect blood samples at two or more time points (e.g., 8:00 AM and 5:00 PM) on the same day.

- Sample Type: Venous blood or finger-prick blood (≥225 µL collected into K3 EDTA tubes).

- 3. Cell Staining & Flow Cytometry:

- Lysing: Use red blood cell lysing solution.

- Staining: Stain with antibody panels for major lymphocyte subsets:

- T Helper Cells: CD3+, CD4+

- Cytotoxic T Cells: CD3+, CD8+

- B Cells: CD19+

- NK Cells: CD3-, CD16+/CD56+

- Analysis: Run samples on a flow cytometer and analyze using software like FlowJo.

- 4. Expected Results:

- As demonstrated, you should detect significant diurnal variation, such as higher percentages of T-helper and B cells at 5:00 PM and a higher percentage of NK cells in the morning [19].

Circadian Immune Signaling Pathways

The following diagram summarizes the proposed mechanistic pathways linking the central circadian clock to rhythmic immune function and vaccine response.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Chronovaccination and Diurnal Immune Research

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Polychromatic Flow Cytometry Panels | Immunophenotyping of rhythmic lymphocyte subsets (T, B, NK cells) and activation markers. | Antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD16/56, CD45RA/RO [19]. |

| ELISA Kits | Quantification of antigen-specific antibody titers (IgG, IgM) in serum post-vaccination. | Virus-specific (e.g., Influenza HA, SARS-CoV-2 Spike) kits. |

| ELISpot Kits | Measurement of antigen-specific T-cell responses (e.g., IFN-γ production). | Critical for assessing cellular immune memory. |

| Circadian/Diarunal Study Design Tools | Managing participant scheduling and sample tracking for time-point experiments. | Defined time windows (e.g., 9-11 AM, 3-5 PM); electronic scheduling systems [29] [30]. |

| Small-Volume Blood Collection Systems | Enables frequent, less invasive sampling for dense diurnal kinetics, especially in vulnerable populations. | Finger-prick lancets and micro-containers (e.g., 200µL Microvette tubes) [19]. |

| Validated Temperature Monitoring | Ensuring vaccine potency is not confounded by improper storage, a critical control. | Digital data loggers with continuous monitoring and alert functions [32]. |

Chrono-immunotherapy is the practice of aligning the administration of immune-based cancer treatments with a patient's internal biological clock, or circadian rhythm. This approach aims to enhance treatment efficacy and reduce side effects by leveraging the fact that the immune system's activity, including the ability of killer T-cells to infiltrate tumors, fluctuates predictably over a 24-hour period [33] [34]. The central pacemaker, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus, coordinates these rhythms throughout the body, regulating everything from sleep-wake cycles and hormone secretion (like cortisol) to immune function [34]. Disruption of these rhythms is linked to worse cancer outcomes, while aligning treatment with circadian biology shows promise for improving patient survival [33] [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core scientific evidence supporting time-of-day administration for immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs)?

Large-scale retrospective clinical studies have consistently shown that patients receiving ICIs earlier in the day experience significantly improved outcomes, including longer progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), across multiple cancer types [34]. Mechanistically, this is supported by the circadian regulation of the immune system. Research has revealed that lymphocytes, the professional killer cells activated by immunotherapy, enter and exit tumors in a circadian fashion, with greater infiltration into the tumor occurring in the morning hours [33]. Animal studies confirm that treatment at the start of the active phase elicits a stronger anti-tumor immune response, an effect that is abolished in animals lacking a circadian clock [34].

Q2: How do I account for individual differences in circadian timing among patients?

A patient's innate timing preference, or chronotype, is a crucial factor. A "one-size-fits-all" approach using wall-clock time may be insufficient because individuals have different internal biological times [34]. Chronotype can be assessed using:

- Validated Questionnaires: Such as the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ) or the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) [34].

- Wearable Biosensors: Devices that continuously monitor locomotor activity, body temperature, or heart rate can provide objective phase markers of the circadian clock [34].

- Biomolecular Snapshot Methods: Emerging tests like TimeTeller can estimate an individual's circadian phase from a single or limited number of biosamples (e.g., blood, saliva) by analyzing the circadian transcriptome, proteome, or metabolome [34].

Q3: What are the major practical challenges in implementing a circadian-enabled clinical trial?

| Challenge | Description | Potential Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Scheduling | Fitting all patient infusions into a limited morning time window creates logistical bottlenecks [33]. | Explore decentralized administration (e.g., at-home infusion) where safe and feasible [33]. |

| Chronotype Assessment | Integrating individual circadian phase measurement into busy clinical workflows [34]. | Use low-burden methods like validated questionnaires or wearable devices [34]. |

| Standardization | Lack of standardized protocols for measuring circadian rhythms (e.g., cortisol, actigraphy) in clinical cancer settings [35]. | Pre-define and validate measurement protocols in the trial's statistical analysis plan. |

| Prospective Data | Much current evidence is retrospective, which is susceptible to bias [34]. | Design prospective, randomized controlled trials that specifically test timing as an intervention [34]. |

Q4: Can we manipulate the circadian clock to make afternoon treatments more effective?

Yes, this is an active area of research. Potential strategies include:

- Pharmacological Resetting: Investigating drugs that can mimic the daily resetting of the central clock [33].

- Time-Restricted Eating (TRE): Controlling meal times is a powerful non-photic cue that can entrain peripheral clocks. Animal studies show that time-restricted feeding can lower cancer incidence and slow tumor growth [33]. Clinical studies are ongoing to see if TRE improves outcomes for cancer therapies in people [33].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: High Inter-Patient Variability in Treatment Response

- Potential Cause: Ignoring patient chronotype, leading to treatment at a suboptimal biological time for "evening-type" individuals [34].

- Solution: Stratify patients by chronotype in the trial design and align ICI administration time accordingly. For example, "larks" (morning-types) may receive treatment in the morning, while "owls" (evening-types) may receive it later in the day [34].

Issue 2: Inability to Detect a Significant Time-of-Day Effect

- Potential Cause: Using a fixed "morning" vs "afternoon" window for all patients without accounting for individual circadian phase, diluting the effect [34].

- Solution: Incorporate an objective measure of internal biological time (e.g., from wearables or a biomolecular test) to define treatment windows based on a patient's unique circadian phase rather than the wall clock [34].

Issue 3: Participant Burden in Circadian Rhythm Assessment

- Potential Cause: Requiring frequent sample collection (e.g., for melatonin or cortisol) over multiple days can lead to poor compliance [35] [36].

- Solution: Leverage less invasive and simpler methods, such as saliva sampling for gene expression analysis [36], using wearable activity sensors [34], or employing single-sample biomarker algorithms to estimate circadian phase [34].

Table 1: Observed Time-of-Day Effects in Cancer Therapy

| Therapy / Intervention | Optimal Timing | Observed Effect | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunotherapy (ICIs) | Morning | Improved progression-free and overall survival [33] [34] | Large-scale retrospective clinical studies [34] |

| Radiation Therapy | Morning | Fewer side effects compared to afternoon administration [33] | Clinical observation [33] |

| Chemotherapy | Varies by drug | Improved efficacy and/or reduced toxicity at specific times [33] | Multiple clinical studies [33] |

| Low-Dose Aspirin | Evening | Greater blood pressure reduction [33] | Clinical trials [33] |

| Statins | Night | Highest effectiveness as target enzyme levels peak at night [33] | Clinical trials [33] |

Table 2: Methods for Assessing Circadian Timing in Clinical Trials

| Method | What It Measures | Pros | Cons | Gold Standard Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dim Light Melatonin Onset (DLMO) | Phase of central clock via melatonin secretion | High accuracy | Logistically challenging, requires controlled dim light | Gold Standard itself |

| Core Body Temperature (CBT) | Rhythm of core body temperature | Objective | Affected by activity, food, and sleep | Correlates with DLMO |

| Saliva Gene Expression (e.g., ARNTL1, PER2) | Phase of peripheral clock in oral mucosa | Non-invasive, suitable for home collection [36] | Requires specialized RNA analysis | Correlates with cortisol acrophase and bedtime [36] |

| Wearable Devices (Actigraphy) | Rest-activity cycles | Continuous, real-world data, low patient burden [34] | A proxy measure, not a direct molecular rhythm | Validated against sleep logs and other markers |

| Chronotype Questionnaires (MEQ, MCTQ) | Self-reported diurnal preference | Very low cost, easy to administer [34] | Subjective, does not measure current physiological state | Correlates with DLMO in healthy populations [34] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Circadian Phase via Saliva Sampling and Gene Expression

This protocol is adapted from recent research demonstrating the feasibility of using saliva for robust circadian rhythm analysis [36].

1. Participant Preparation and Sampling:

- Instruct participants to collect unstimulated whole saliva at 3-4 predefined time points (e.g., 8:00, 14:00, 20:00) over 2 consecutive days.

- Use collection kits containing RNA stabilizer (e.g., RNAprotect). A 1:1 ratio of saliva to stabilizer with a 1.5 mL sample volume has been shown to provide optimal RNA yield and quality [36].

- Samples should be stored at -80°C immediately after collection until RNA extraction.

2. RNA Extraction and Analysis:

- Extract total RNA from saliva samples using a standardized commercial kit suitable for saliva.

- Analyze the expression of core clock genes (e.g., ARNTL1, NR1D1, PER2, PER3) via reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). These genes have shown robust, detectable circadian rhythms in saliva and oral mucosa [36].

- Generate circadian phase maps (e.g., acrophase - the time of peak expression) for each participant from the gene expression time series.

3. Data Integration:

- Correlate gene expression acrophases with other circadian markers, such as cortisol levels from the same saliva samples or bedtimes recorded by participants [36]. This validates the molecular data against established rhythms.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Chronotype-Informed Dosing Schedule

1. Chronotype Stratification:

- At trial enrollment, have participants complete the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) to determine their chronotype (Morning type, Intermediate, Evening type) [34].

- Randomization should stratify patients based on chronotype to ensure balanced groups.

2. Treatment Administration:

- Morning-type ("Larks") and Intermediate-type patients are scheduled to receive their ICI infusions in the morning (e.g., between 08:00 and 11:00).

- Evening-type ("Owls") patients are scheduled to receive their ICI infusions in the late morning or afternoon (e.g., between 11:00 and 14:00). This model is inspired by the successful outcomes of the Treatment in Morning versus Evening (TIME) trial for hypertension [34].

3. Monitoring and Adherence:

- Use clinic logs to strictly record infusion start times.

- Consider using wearable activity trackers throughout the trial to monitor for shifts in rest-activity cycles that might indicate changes in circadian phase [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Circadian Clinical Research

| Item / Reagent | Function in Chronotherapy Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Saliva RNA Collection Kit | Non-invasive collection and stabilization of RNA from saliva for gene expression analysis [36]. | Measuring daily rhythms of core clock genes (e.g., PER2, ARNTL1) in participants [36]. |

| Validated Chronotype Questionnaire (e.g., MCTQ) | Assessing an individual's innate diurnal preference for activity and rest as a proxy for circadian phase [34]. | Stratifying patients in a clinical trial into morning, intermediate, and evening chronotype groups for personalized dosing [34]. |

| Wearable Activity Monitor (Actigraph) | Continuously monitoring rest-activity cycles to objectively characterize a participant's circadian rhythm in their home environment [34]. | Providing a longitudinal proxy measure of circadian stability and sleep-wake patterns during a therapy cycle [34]. |

| Cortisol ELISA Kit | Quantifying cortisol levels in saliva or serum; cortisol is a key circadian hormone with a robust morning peak [35] [36]. | Validating the phase of the central circadian clock and investigating HPA axis dysfunction in cancer patients [35]. |

| TimeTeller or similar algorithm | A computational tool that estimates circadian phase and rhythm disruption from a single or limited number of biosamples using transcriptomic or metabolomic data [34]. | Determining a patient's internal biological time from a single blood draw, reducing the burden of full time-series sampling [34]. |

Visual Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Circadian Regulation of Anti-Tumor Immunity

Diagram 2: Personalized Chronotherapy Dosing Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is it important to account for diurnal rhythms in biomarker discovery studies? The circadian clock exerts strict control over immune function, including the trafficking of leukocytes between tissues and the production of inflammatory mediators. Consequently, the concentration of many immune-related proteins in the blood oscillates over the 24-hour cycle. Failing to standardize sample collection times can introduce significant intraindividual variation, masking true disease-associated signals and reducing the reliability of potential biomarkers [37].

Q2: What are the primary biological drivers of daily variation in the plasma proteome? Two key drivers are:

- The Central Clock: The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus, entrained by light-dark cycles, synchronizes rhythms throughout the body via neuropeptides and autonomic innervation [37].

- The Molecular Clock: This cell-autonomous mechanism involves a transcriptional-translational feedback loop. The core components are CLOCK and BMAL1 proteins, which activate genes including their own repressors, PER and CRY. This loop, along with secondary circuits involving REV-ERBα and RORα, generates 24-hour rhythms in gene expression, including those of immune proteins [37].

Q3: Which immune processes are known to be under circadian control? Circadian rhythms govern several key immune functions relevant to biomarker studies:

- Leukocyte Trafficking: The number of circulating immune cells changes dynamically over the day, driven by rhythmic expression of migration factors like CXCL12 and adhesion molecules [37].