In Silico Mechanistic Modeling of the Immune Response to Burn Injuries: From Cellular Dynamics to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of in silico mechanistic modeling approaches for deciphering the complex immune response following burn injuries.

In Silico Mechanistic Modeling of the Immune Response to Burn Injuries: From Cellular Dynamics to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of in silico mechanistic modeling approaches for deciphering the complex immune response following burn injuries. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of post-burn immunology, details cutting-edge computational methodologies like Agent-Based Models and neural networks, and addresses key challenges in model optimization and validation. By synthesizing recent scientific advances, this resource highlights how these computational tools can identify critical therapeutic targets, predict patient-specific outcomes, and ultimately guide the development of novel treatment strategies to improve burn care.

Decoding the Complexity of Post-Burn Immunology: The Foundation for In Silico Models

Severe burn injury triggers a complex and prolonged inflammatory cascade, characterized by a dynamic and often dysregulated immune response that evolves from acute to chronic phases [1]. This response is not a linear sequence but a unstable equilibrium between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory forces, whose balance determines clinical outcomes such as sepsis, multiple organ dysfunction, and mortality [2]. The initial Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) is characterized by a massive release of pro-inflammatory mediators, which is subsequently counterbalanced by a Compensatory Anti-Inflammatory Response Syndrome (CARS) [1]. Advances in medical care have allowed patients to survive the initial acute phase, leading to the recognition of a persistent third phase known as Persistent Inflammation, Immunosuppression, and Catabolism Syndrome (PICS), which can last for months to years post-injury [1]. Understanding the temporal dynamics of this biphasic response is crucial for developing targeted immunomodulatory therapies and improving patient outcomes.

Characterizing the Phases: From Acute SIRS to Chronic PICS

Acute Inflammatory Phase (0-72 hours post-injury)

The acute phase initiates within hours of injury and is mediated by the innate immune system. Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released from necrotic tissue, such as High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) and mitochondrial DNA, are recognized by Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs) on immune cells including macrophages and neutrophils [1] [3]. This recognition triggers the release of a storm of pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) [2] [3]. These cytokines recruit additional immune cells to the site of injury and initiate the acute phase response, characterized by the liver production of C-reactive protein (CRP) and other acute phase proteins [2] [3]. The acute phase is a necessary response for tissue protection and initial repair; however, its excessive and persistent magnitude contributes to early complications such as distributive shock and organ failure [1] [4].

Chronic Inflammatory Phase (≥14 days post-injury)

Following the initial hyperinflammatory state, a prolonged phase of immune dysfunction ensues, now better defined as PICS [1]. This phase is marked by concurrent persistent inflammation, broad immunosuppression, and significant catabolism. A critical feature is a shift in adaptive immunity, characterized by suppressed T-helper 1 (Th1) responses, a shift towards Th2-type responses, T cell exhaustion, and increased activity of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [1]. Macrophages polarize toward an M2 phenotype, and the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 creates an environment susceptible to hospital-acquired infections [1] [4]. Recent research highlights the role of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in sustaining this chronic phase; EVs isolated late after burn injury carry an immunosuppressive protein cargo that reprograms macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory state, thereby perpetuating immune paralysis [4].

Table 1: Key Mediators in Post-Burn Inflammatory Phases

| Mediator Type | Specific Molecule | Acute Phase (0-72h) | Chronic Phase (≥14 days) | Primary Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-inflammatory Cytokines | IL-6 | Sharp increase, peaks 1-4 days [2] [3] | Can remain elevated for years [3] | Macrophages, neutrophils |

| IL-8 | Rapid increase in first 4 days [2] | Persists for several weeks [2] | Epithelial cells, macrophages | |

| TNF-α | Surge within 2.5 days [3] | Local persistence for weeks [3] | Macrophages, neutrophils | |

| IL-1β | Increases from day 1, peaks day 3 [2] [3] | — | Macrophages | |

| Anti-inflammatory Cytokines | IL-10 | Increases from day 1, peaks early [2] [3] | Gradual decrease over weeks [2] | M2 macrophages, T cells |

| Chemokines | MCP-1 | Early increase [2] | Correlates with mortality [2] | Endothelial cells, macrophages |

| Damage Signals | HMGB1 | Released from damaged tissue [1] | — | Necrotic cells |

| Acute Phase Proteins | C-reactive Protein (CRP) | Sharp increase, persists for months [2] | — | Liver |

Quantitative Biomarker Dynamics and Correlations with Outcomes

The systematic measurement of inflammatory mediators provides critical prognostic information and guides potential therapeutic interventions. Elevated levels of specific cytokines have been consistently correlated with adverse clinical outcomes. For instance, early increases in MCP-1, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 are significantly correlated with 28-day mortality [2]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis has confirmed that an elevated admission Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) is an independent predictor of mortality in burn patients [2].

The dynamic nature of these biomarkers is evident in their temporal patterns. IL-6 increases sharply within the first 1-4 days post-burn and can remain elevated for months or even years, with levels correlating with the percentage of total body surface area (TBSA) burned [3]. Non-survivors often present with significantly higher plasma IL-6 levels on the day of injury compared to survivors [3]. Similarly, IL-8 serum levels can be dramatically elevated—up to 2000-fold compared to healthy controls [3]. Anti-inflammatory mediators like IL-10 peak on the first day post-burn and gradually decrease, with the highest concentrations correlating with both TBSA and the development of sepsis [3].

Table 2: Biomarker Associations with Clinical Outcomes in Burn Patients

| Biomarker | Correlation with Injury Severity | Association with Mortality | Association with Sepsis/Infection | Other Clinical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | Correlates with %TBSA and depth [3] | Higher in non-survivors [3] | — | Stimulates acute phase proteins, angiogenesis [3] |

| IL-8 | — | — | — | Neutrophil recruitment, tissue remodeling [3] |

| IL-10 | Correlates with %TBSA [3] | Levels >60 pg/ml distinguish survivors/non-survivors [5] | Higher in septic vs. non-septic patients [3] | — |

| MCP-1 | Correlates with burn severity [3] | Higher in non-survivors on day 1 [2] [3] | — | Recruits monocytes to injury site [3] |

| NLR | — | Independent predictor of mortality [2] | — | Systemic inflammation index [2] |

| HMGB1 | Positive correlation with injury size (murine model) [3] | — | — | DAMP signaling via TLR4 [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Immune Monitoring

Protocol 1: Longitudinal Cytokine Profiling in Human Plasma

Objective: To quantitatively measure the dynamic changes in pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels in burn patient plasma over time, from the acute phase through the chronic phase.

Materials and Reagents:

- Sodium Heparin Tubes: For blood collection and plasma separation.

- Multiplex Bead-Based Immunoassay Kit: Validated for human cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-1β).

- Luminex Platform or ELISA Plate Reader: For signal detection and quantification.

- Recombinant Cytokine Standards: For generating standard curves.

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Collect venous blood from severe burn patients (e.g., >20% TBSA) at predetermined time points: admission (<6h), 24h, 72h, 7 days, 14 days, and 30 days post-injury. Process samples within 1 hour by centrifugation at 2,000 x g for 15 minutes to isolate plasma. Store aliquots at -80°C.

- Assay Procedure:

- Thaw plasma samples on ice and clarify by high-speed centrifugation (10,000 x g for 10 minutes) to remove particulates.

- Follow the manufacturer's protocol for the multiplex immunoassay. Briefly, add standards and samples to the bead plate in duplicate.

- Incubate, wash, then add biotinylated detection antibodies.

- After another incubation and wash, add streptavidin-PE, then read on the Luminex analyzer.

- Data Analysis: Use software to calculate cytokine concentrations from standard curves. Perform statistical analysis (e.g., ANOVA with post-hoc tests) to compare levels across time points and correlate with clinical outcomes (e.g., sepsis, mortality) using logistic regression models.

Protocol 2: Isolation and Proteomic Analysis of Immunomodulatory Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)

Objective: To isolate EVs from patient plasma at different post-burn phases and characterize their protein cargo to understand their role in immune reprogramming.

Materials and Reagents:

- Differential Centrifugation Equipment: Ultracentrifuge and fixed-angle rotors.

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), Filtered (0.22 µm): For EV washing and resuspension.

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) Instrument: e.g., ZetaView QUATT, for EV quantification and sizing.

- Mass Spectrometry-Grade Reagents: For proteomic sample preparation (e.g., trypsin, RIPA buffer, protease inhibitors).

Methodology:

- EV Isolation from Plasma:

- Centrifuge plasma at 2,000 x g for 20 minutes to remove cells.

- Transfer supernatant and centrifuge at 10,000 x g for 30 minutes to remove cell debris.

- Ultracentrifuge the resulting supernatant at 21,000 x g for 1 hour at 4°C to pellet EVs.

- Wash the pellet in filtered PBS and repeat the ultracentrifugation step.

- Resuspend the final EV pellet in 100-200 µL of saline and filter through a 0.22 µm syringe filter. Store at -80°C [4].

- EV Characterization: Dilute an aliquot of EVs in filtered PBS and analyze using NTA to determine particle concentration (particles/mL) and mode size (nm).

- Proteomic Analysis:

- Lyse EVs in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors.

- Digest proteins using trypsin and desalt the resulting peptides.

- Analyze peptides by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Identify proteins and perform pathway analysis using bioinformatics tools (e.g., Gene Ontology, KEGG) to identify enriched biological processes in early vs. late EVs.

In Silico Modeling of Post-Burn Inflammation

Computational models have emerged as powerful tools to decipher the complexity of the post-burn immune response, offering a platform for hypothesis testing and in silico experimentation.

Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) of Acute Inflammation

Objective: To develop a spatio-temporal model simulating cellular interactions and cytokine dynamics in the first 0-4 days post-burn.

Model Framework: The Glazier-Graner-Hogeweg (GGH) model, a type of ABM, can be implemented using CompuCell3D software [6] [7]. The simulation domain is separated into blood and tissue compartments.

Model Components:

- Agents (Cells): Model key immune cells as independent agents, including mast cells, neutrophils, and macrophages. Each agent is motile and exhibits chemotaxis based on concentration gradients of solutes [6].

- Solutes (Signaling Molecules): Define pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α), anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10), and inflammation-triggering factors (e.g., DAMPs). Solutes diffuse throughout the domain based on their concentration profiles [6].

- Rules and Interactions: Program behavioral rules for agents. For example, neutrophils are recruited to the tissue compartment by gradients of IL-8; activated macrophages secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines; endothelial cells express adhesion molecules.

Simulation and Output: The model tracks changes in cell counts and cytokine levels over time and space. A key finding from such models is the identification of the initial endothelial cell count as a pivotal parameter determining the intensity and progression of acute inflammation [6] [8].

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) for Cytokine Prediction

Objective: To create a surrogate model that approximates and forecasts cytokine concentration dynamics from ABM simulations with lower computational cost.

Workflow:

- Data Generation: Run multiple simulations of the baseline ABM to generate extensive spatio-temporal data on cytokine concentrations.

- Data Preprocessing: Clean the data and transform it into a suitable format for neural network training, such as a time-series dataset with spatial grids.

- Model Training: Implement and train a Spatio-Temporal Attention Long Short-Term Memory (STA-LSTM) neural network. This architecture is designed to capture both temporal dependencies and spatial relationships in the cytokine data. The model is evaluated using metrics like Mean Squared Error and R-squared [7].

- Prediction: Use the trained STA-LSTM model to predict cytokine concentrations over time and space under different initial conditions, providing a rapid forecasting tool.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Post-Burn Immunity

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example / Target |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex Cytokine Panels | Simultaneous quantification of multiple cytokines in serum/plasma. | IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-1β [2] [3] |

| Anti-HMGB1 Antibodies | Detection and inhibition of DAMP signaling. | Neutralizing HMGB1 to study its role via TLR4 [1] [3] |

| Luminex/xMAP Technology | High-throughput, multiplexed immunoassay platform. | Profiling cytokine kinetics from minimal sample volume [3] |

| EV Isolation Kits | Purification of exosomes and microvesicles from biofluids. | Differential centrifugation for plasma EV isolation [4] |

| NTA Instrumentation | Characterization of EV size and concentration. | ZetaView QUATT system [4] |

| CompuCell3D Software | Platform for GGH/ABM model implementation. | Simulating immune cell migration and interaction [6] [7] |

| Primary Cell Cultures | In vitro validation of immune cell functions. | Human THP-1 macrophages for EV stimulation assays [4] |

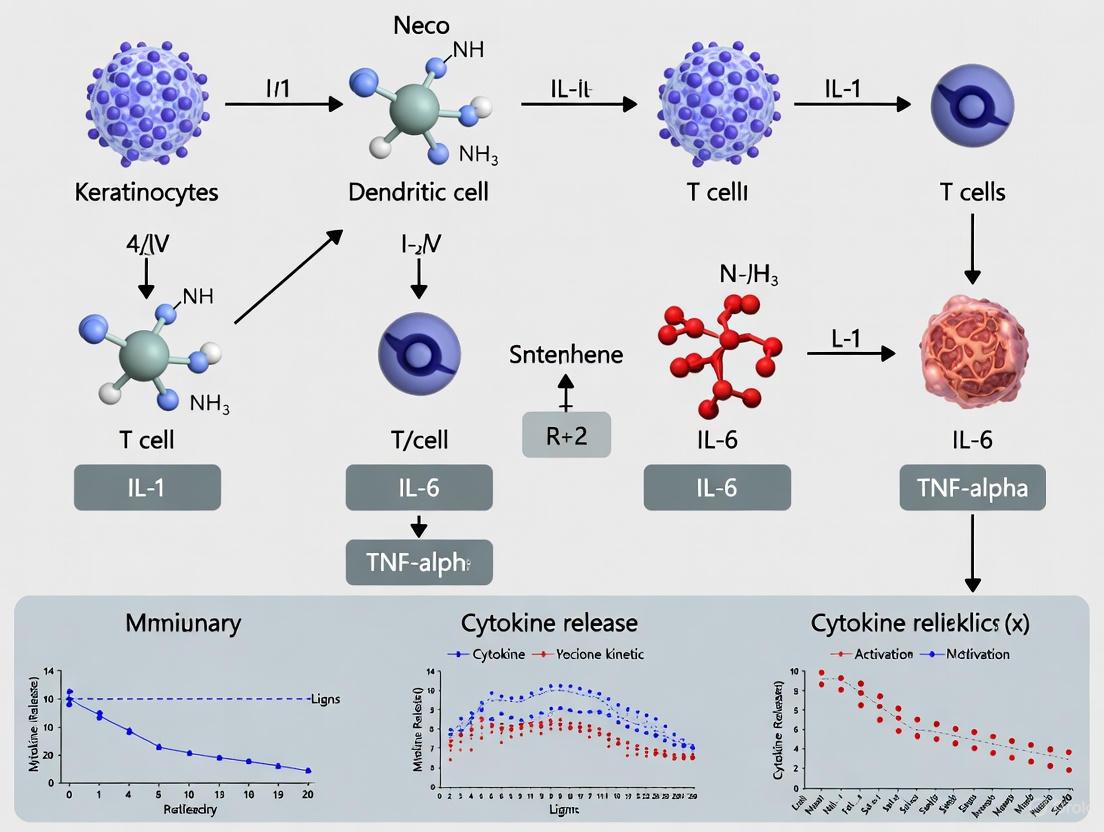

Signaling Pathways and Conceptual Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate key signaling pathways and experimental workflows central to post-burn immune research.

The immune response to burn injury is a carefully orchestrated process involving complex interactions between various cellular players. Among these, neutrophils, macrophages, and endothelial cells emerge as critical regulators that coordinate the transition from inflammation to tissue repair. Understanding the precise roles and interactions of these cells provides valuable insights for developing targeted therapeutic strategies and building accurate in silico models of burn pathophysiology.

This application note synthesizes current research findings to detail the specific functions, activation mechanisms, and temporal dynamics of these key cellular players during burn immune responses. We further provide detailed experimental protocols for investigating their roles and visualize critical signaling pathways to support mechanistic modeling efforts.

Quantitative Profiles of Key Cellular Players

The following tables summarize quantitative data and temporal dynamics for neutrophils, macrophages, and endothelial cells in burn injury responses, providing essential parameters for computational modeling.

Table 1: Temporal Dynamics and Key Functions of Cellular Players in Burn Injury

| Cell Type | Key Functions in Burn Response | Peak Activation Time | Phenotypic Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | First responders; phagocytosis; release of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6; matrix production; bacterial clearance [2] [9] | Immediate surge, persistent for weeks [9] | CD15⁺; MPO⁺ [9] |

| Macrophages | Phagocytosis; debris clearance; phenotype transition (M1→M2); release of cytokines & growth factors; tissue repair [6] [10] | M1: Days 1-3; M2: Days 3+ [6] [10] | M1: CD68⁺, CD86⁺; M2: CD206⁺ [10] [11] |

| Endothelial Cells | Initiate inflammatory response; express adhesion molecules & chemokines; recruit immune cells; angiogenesis [6] | Early responder (0-4 days post-burn) [6] | N/A |

Table 2: Secretory Profile and Associated Experimental Models

| Cell Type | Key Secretory Products | Primary Experimental Models | Computational Modeling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, collagen, matrix proteins [2] [12] | Human burn eschar analysis [9], murine models [12] | Prolonged presence vs. normal healing; matrix production function |

| Macrophages | M1: IL-1β, TNF-α, iNOS; M2: IL-4, IL-13, EGF, bFGF, VEGF [10] | THP-1 cell line, RAW 264.7 cells, murine burn models [10] [11] [13] | Response to mechanical stretch; non-monotonic input-output relationships |

| Endothelial Cells | Adhesion molecules, chemokines (e.g., IL-8) [6] | In silico modeling (GGH method) [6] | Pivotal parameter for model intensity; initial cell count is crucial |

Detailed Cellular Mechanisms and Functions

Neutrophils: First Responders and Barrier Strengtheners

Neutrophils are the first immune cells recruited to the burn site, showing an immediate and strong increase that persists for weeks, unlike the transient response observed in normal wound healing [9]. Their classical functions include phagocytosing microbes and necrotic cells, and releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 to attract monocytes and macrophages [2].

Recent research has revealed a previously unexpected function of neutrophils: producing collagen and other matrix proteins that strengthen the skin barrier [12]. This specialized population of skin-resident neutrophils helps maintain skin resistance and integrity under normal conditions and is activated in response to injury to generate protective structures around wounds that prevent bacterial entry [12]. Their activity follows a day-night pattern, adjusting extracellular matrix production according to the body's circadian cycle, resulting in higher skin resistance at night [12].

Macrophages: Dynamic Regulators of Inflammation and Repair

Macrophages play pivotal roles throughout all stages of burn wound healing, demonstrating remarkable plasticity [10]. Following injury, pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages are recruited to the wound site to release cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α) and facilitate clearance of bacteria and deceased cells [10]. As tissue repair commences, the macrophage population undergoes a critical transition toward an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, which releases anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-13) and growth factors (EGF, bFGF, VEGF) that support tissue regeneration [10].

Macrophages exhibit a non-monotonic response to mechanical stretch across different amplitudes (7%-21%), with 15% stretch promoting optimal M2 polarization, enhanced release of anti-inflammatory factors, and activation of YAP/TAZ mechanotransduction pathways [10]. This mechanical responsiveness highlights how physical cues in the wound environment can shape immune function.

Therapeutic strategies can target macrophage polarization. For instance, Isosteviol has been shown to upregulate MMP-9 in macrophages, leading to M2 polarization and reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-2 and TNF-α [13]. Similarly, Lyophilized Horizontal Platelet Rich Fibrin (Ly-H-PRF) reduces LPS-induced macrophage M1 polarization while promoting M2 polarization [11].

Endothelial Cells: Orchestrators of Immune Cell Recruitment

Endothelial cells are among the first responders at the site of burn damage and play a crucial role in initiating and balancing the inflammatory response [6]. Among their primary functions, they initiate the inflammatory response during the acute phase by expressing adhesion molecules and chemokines, thereby facilitating the recruitment of immune cells such as neutrophils and monocytes to the wound area [6].

In silico modeling approaches have highlighted the pivotal role of the initial endothelial cell count as a key parameter determining the intensity and progression of acute inflammation during the critical 0-4 days post-burn period [6] [8]. These models separate the simulation domain into blood and tissue compartments, with endothelial cells mediating the critical interactions between these compartments.

Experimental Protocols for Cellular Analysis

Protocol 1: Immune Cell Isolation from Burn Wound Tissue (Eschar)

This protocol adapts the methodology used by Mulder et al. (2022) for isolating viable immune cells from human burn wound tissue for flow cytometric analysis [9].

Reagents and Materials:

- RPMI 1640 medium with 1% penicillin/streptomycin

- Collagenase I (80 mg/mL in PBS)

- FCM buffer (PBS with 1% BSA, 0.05% sodium azide, and 1 mM EDTA)

- Erythrocyte lysis buffer (1.5 mM NH₄Cl, 0.1 mM NaHCO₃, 0.01 mM EDTA)

- C-tubes (Miltenyi Biotec)

- Cell strainers (500 µm and 40 µm)

- gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec) or similar tissue dissociator

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect burn wound tissue (eschar) during surgical debridement and store in RPMI 1640 with antibiotics at 4°C overnight.

- Tissue Processing: Take approximately 600 mg of tissue from viable areas (white or red with bleeding spots). Cut into small pieces and distribute into 2 C-tubes, each containing 5 mL of RPMI 1640 with antibiotics.

- Mechanical Dissociation: Place C-tubes on gentleMACS dissociator and run program "B" for initial dissociation.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Add 150 µL of collagenase I solution (80 mg/mL) to each tube. Incubate in a shaking water bath at 37°C for 1 hour.

- Secondary Dissociation: Return tubes to dissociator and run program "B" again.

- Cell Strainer Filtration: Pass the cell suspension sequentially through 500 µm and 40 µm cell strainers.

- Erythrocyte Lysis: Centrifuge at 450 × g for 10 minutes, discard supernatant. Resuspend pellet in erythrocyte lysis buffer for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Cell Washing: Add 20 mL FCM buffer and centrifuge at 450 × g for 10 minutes.

- Cell Counting: Resuspend in 5 mL FACS buffer and count cells using a flow cytometer or hemocytometer.

Applications: This protocol enables subsequent flow cytometric analysis of immune cell populations, including neutrophil maturity assessment, macrophage polarization status, and lymphocyte subtyping.

Protocol 2: Macrophage Stretch Assay for Mechanobiological Studies

This protocol describes the application of static mechanical stretch to macrophages in vitro to study how mechanical cues in the wound environment influence their phenotype, based on the methods of Wang et al. (2025) [10].

Reagents and Materials:

- THP-1 human monocytic cell line or primary human monocytes

- PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate) for THP-1 differentiation

- Flexible-bottom 6-well culture plates (precoated with type I collagen)

- Custom cell-stretching device (vacuum pump, pressure reservoir, negative pressure controller)

- Macrophage polarization markers: anti-CD68, CD86, CD206 antibodies

Procedure:

- Macrophage Differentiation: Seed THP-1 cells at 2×10⁵ cells/well in flexible-bottom plates. Differentiate into macrophages using 100 ng/mL PMA for 48 hours.

- Cell Stretching: Culture differentiated macrophages for 12 hours to allow attachment. Apply static mechanical stretch at desired amplitudes (7%, 15%, 21%) for 24 hours using the stretching device.

- Conditioned Medium Collection: Collect conditioned medium (MS-CM) from stretched macrophages and control (unstretched) macrophages. Centrifuge at 500 × g for 10 minutes, then at 2000 × g for 5 minutes to remove cells and debris.

- Flow Cytometric Analysis: Analyze macrophage polarization using fluorescence-conjugated antibodies against CD68 (pan-macrophage), CD86 (M1 marker), and CD206 (M2 marker).

- Functional Assays: Apply MS-CM to keratinocytes, fibroblasts, or endotheliocytes to assess paracrine effects on migration, proliferation, and tube formation.

Applications: This assay enables investigation of how mechanical forces in the wound environment influence macrophage polarization and subsequent paracrine signaling to other skin cells involved in tissue repair.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Macrophage Polarization Signaling Pathway

The following diagram illustrates key signaling pathways involved in macrophage polarization in response to burn injury and mechanical stimuli, integrating findings from multiple studies [10] [13]:

Experimental Workflow for Burn Immune Response Studies

This workflow diagrams the integrated experimental approach for studying cellular immune responses to burn injury, from sample processing to computational modeling:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Burn Immune Responses

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Models | THP-1 human monocytic cell line, RAW 264.7 murine macrophages, primary HUVECs | In vitro mechanistic studies of immune cell function | [10] [11] |

| Macrophage Polarization Reagents | PMA (for THP-1 differentiation), LPS (M1 polarization), IL-4/IL-13 (M2 polarization) | Directing macrophage phenotype for functional assays | [10] [11] |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Anti-human: CD14, CD16, CD45, CD3, CD15, CD68, CD86, CD206 | Immune cell phenotyping and polarization assessment | [9] [10] |

| Mechanical Stretch Equipment | Flexible-bottom culture plates, vacuum pump systems, pressure controllers | Studying mechanobiology of immune cells in wound environment | [10] |

| Cytokine Analysis Kits | Multiplex cytokine arrays (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, VEGF etc.) | Secretome profiling of immune cells and tissue explants | [9] [3] |

| Computational Modeling Tools | Glazier-Graner-Hogeweg (GGH) method, Agent-based modeling (ABM) platforms | In silico simulation of immune dynamics | [6] [8] |

The coordinated functions of neutrophils, macrophages, and endothelial cells create a complex network that drives the immune response to burn injury. For in silico modeling, each cell type presents specific parameters critical for accurate simulation: the prolonged presence and matrix-producing functions of neutrophils; the phenotypic plasticity and mechanoresponsiveness of macrophages; and the orchestrating role of endothelial cells in initial immune cell recruitment.

The experimental protocols and signaling pathways detailed in this application note provide a framework for generating quantitative data to parameterize computational models. Future modeling efforts should particularly focus on the non-linear relationships between mechanical stimuli and macrophage polarization, the circadian regulation of neutrophil function, and the feedback loops between endothelial cell activation and immune cell infiltration. Such integrated experimental-computational approaches will accelerate the development of targeted interventions to modulate burn immune responses for improved patient outcomes.

Severe burn injuries trigger a complex and dynamic immune response that originates locally but rapidly progresses to a systemic inflammatory state, often culminating in single or multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). This application note synthesizes current clinical and computational research to outline the pathophysiological mechanisms and key biomarkers linking local burn trauma to remote organ failure. We provide structured experimental protocols and in silico modeling approaches to aid researchers in investigating these critical pathways and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

Severe burn trauma initiates a profound systemic stress response characterized by a massive, and often prolonged, release of inflammatory mediators. Unlike other forms of trauma, this inflammatory state can persist for months post-injury, creating a unique clinical challenge [14]. The initial local destruction of tissue releases damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which activate both local and systemic immune cells, triggering a cytokine storm. This response is not a linear sequence but a dynamic and unstable equilibrium between pro- and anti-inflammatory forces, where the persistence of dysregulation, rather than the initial cytokine magnitude, often determines patient outcomes [15]. The failure to re-establish homeostasis leads to a catabolic, hypermetabolic state that can destroy host tissue and propagate organ injury far from the original burn site [14].

The transition from local injury to systemic complication is a critical focus for both clinical management and pharmaceutical development. Understanding the precise mechanisms and timing of organ failure is essential for risk stratification and the design of effective anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving therapies.

Key Pathophysiological Pathways and Clinical Evidence

The Mediators of Systemic Inflammation

The systemic inflammatory response is driven by a complex network of soluble mediators and cellular actors. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and IL-1β are released early and in abundance, while anti-inflammatory mediators like IL-10 attempt to counterbalance this response [15] [6]. The failure of these compensatory anti-inflammatory mechanisms is a key factor in the progression to organ dysfunction [15]. Furthermore, acute-phase proteins and complement fragments contribute to the widespread endothelial damage and microvascular hyperpermeability that underlies distributive shock and organ hypoperfusion [15] [16].

Table 1: Key Inflammatory Mediators in Post-Burn Systemic Complications

| Mediator Type | Key Examples | Primary Source | Role in Systemic Complications & Organ Dysfunction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-inflammatory Cytokines | IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, IL-1β | Immune cells (e.g., macrophages, neutrophils) | Drive hypermetabolism, fever, acute phase response; induce endothelial dysfunction and direct tissue injury [15] [6]. |

| Anti-inflammatory Cytokines | IL-10 | Immune cells (e.g., M2 macrophages) | Counteracts pro-inflammatory response; failure is associated with poor outcomes and persistent inflammation [15]. |

| Acute Phase Proteins | C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | Liver | Marker of systemic inflammation; contributes to opsonization and complement activation [15]. |

| Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) | HMGB1, Heat Shock Proteins | Damaged/necrotic cells | Trigger initial immune activation via pattern recognition receptors (e.g., TLRs), perpetuating the cytokine storm [6]. |

Temporal Patterns of Organ Failure

Clinical studies have revealed that organ failure post-burn follows a distinct and predictable temporal pattern, which has critical implications for monitoring and intervention strategies.

Table 2: Temporal Patterns of Organ Failure Following Major Burn Injury

| Organ System | Incidence & Onset | Key Clinical Associations |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | Highest incidence throughout acute hospital stay [17]. | Associated with cardiomyocyte apoptosis, dilative cardiomyopathy, and toxic agents [17]. |

| Respiratory | Highest incidence in the early phase; decreases starting ~5 days post-burn [17]. | Strongly linked to inhalation injury and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) [15] [17]. |

| Hepatic | Incidence increases with the length of hospital stay; high mortality in the late phase [17]. | Linked to the hypermetabolic response, vast catabolism, and drug-induced toxicity [17]. |

| Renal | Lower incidence but associated with very high mortality, especially in the first 3 weeks [17]. | Results from initial trauma, myoglobinuria, and inappropriate fluid resuscitation [17]. |

| Hematologic | Very common (up to 68.6%) in major burns, often occurring early (<5 days) [16]. | A frequent component of early multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) [16]. |

The failure of three or more organs is associated with a very high mortality rate, underscoring the critical need for early prediction and prevention [17].

Predictive Clinical Factors for Organ Dysfunction

Identifying patients at highest risk for MODS enables targeted, intensive care. Large-scale clinical studies have consistently identified several key risk factors.

Table 3: Clinical Predictors of Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS) after Severe Burns

| Predictor | Association with MODS | Clinical Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Total Body Surface Area (TBSA) | Strong, independent predictor. A TBSA ≥55% significantly increases risk [16]. | Odds Ratio (OR): 3.83; 95% CI: 1.29–11.37 for early MODS [16]. |

| Inhalation Injury | Strong, independent predictor, particularly for early-onset MODS (within 3 days) [18]. | Significantly increases incidence of MOF (57% vs. 29% without) [17]. |

| Hypoalbuminemia | Independent predictor. Serum albumin <2.1 g/dL upon admission is a significant risk factor [16]. | OR: 3.43; 95% CI: 1.01–11.57 for early MODS [16]. |

| Advanced Age | Independent predictor of MODS in adult populations [18]. | Associated with increased mortality and morbidity [14]. |

| Elevated Lactate & Denver Score | Predictive of late-onset MODS (after 3 days) [18]. | Indicates tissue hypoperfusion and established organ stress [18]. |

In Silico Modeling of the Post-Burn Immune Response

Computational models provide a powerful platform for investigating the complex, non-linear dynamics of the immune response to burns without the ethical and practical constraints of purely clinical or animal studies.

Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) of Acute Inflammation

The Glazier-Graner-Hogeweg (GGH) method, a type of Agent-Based Model, simulates the behavior and interactions of individual cells (agents) within a defined spatial environment [6] [8]. In a typical model setup, the domain is separated into blood and tissue compartments. Key cellular agents include mast cells, neutrophils, and macrophages, while solutes comprise pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and DAMPs [6]. These agents interact based on rules derived from experimental data, such as secreting cytokines and exhibiting chemotaxis along concentration gradients.

Simulations from day 0 to 4 post-burn have identified the initial endothelial cell count as a pivotal parameter determining the intensity and progression of acute inflammation [6] [8]. Endothelial cells are among the first responders, initiating the inflammatory response by expressing adhesion molecules and chemokines that recruit immune cells to the site of injury and systemically [6].

Diagram 1: From Local Burn to Systemic Organ Dysfunction. This pathway illustrates the key steps through which a local burn injury propagates to cause remote organ failure, highlighting the central role of endothelial activation.

Neural Networks as Surrogate Models

While ABMs are highly detailed, they are computationally intensive. To address this, surrogate neural network (NN) models are being developed to approximate ABM simulations, enabling faster predictions of cytokine dynamics over time and space [7]. Architectures like STA-LSTM (Spatio-Temporal Attention Long Short-Term Memory) have demonstrated superior performance in capturing the temporal and spatial dependencies of cytokine concentrations, outperforming other models in statistical metrics such as Mean Squared Error and R-squared [7]. Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) also show promise by incorporating physical laws governing cytokine diffusion and cell interaction, improving the biological plausibility of predictions [7].

Experimental Protocols and Research Tools

Protocol: Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy for Assessing Red Blood Cell Damage

This protocol quantifies the degree of systemic burn injury by measuring the electrical impedance of blood, which changes with the proportion of damaged (heated) red blood cells (HRBCs) [19].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Collect whole blood (e.g., swine model) within 12 hours of draw, using trisodium citrate (3.28%) as an anticoagulant (1:9 ratio).

- To mimic varying degrees of burn injury, centrifuge separate aliquots at 2000× g for 30 min to isolate plasma, RBCs, and heated RBCs (HRBCs).

- Create HRBCs by incubating whole blood in a thermostatic water bath at 55°C for 1 hour before centrifugation.

- Mix plasma with RBCs and HRBCs in different proportions (e.g., HCT from 20% to 80%; HHCT from 0% to 40%) to create experimental samples simulating different injury severities.

2. Impedance Measurement:

- Use an impedance analyzer (e.g., Hioki IM7581) with a fixture and a custom cuvette with copper electrodes (e.g., 10mm x 20mm, 2mm gap).

- Load the sample into the cuvette and measure electrical impedance across a frequency sweep from 100 kHz to 300 MHz with an applied current of 10 mA.

- Perform all measurements under controlled room temperature (e.g., 25°C).

3. Data Analysis:

- Plot Nyquist plots (imaginary vs. real impedance) for each sample.

- Extract the characteristic frequency (f~c~) and the corresponding imaginary part of the impedance (Z~Imt~) at the peak of the plot.

- Correlate Z~Imt~ with the HHCT. A linear relationship is expected: Z~Imt~ = -2.56 HHCT - 2.01 (R² = 0.96) [19].

- Alternatively, fit the data to a seven-parameter equivalent circuit model and extract the plasma resistance (R~p~), which also correlates linearly with HHCT [19].

Protocol: Cytokine Profiling for Predicting Organ Failure

Monitoring the dynamic changes in cytokine levels is crucial for understanding the systemic inflammatory state.

1. Sample Collection:

- Collect blood from burn patients at standardized time points: admission, pre-operatively, and then serially post-operatively (e.g., every 5 days for 4 weeks) [17].

- Draw blood into serum-separator tubes and centrifuge for 10 minutes at 1320 rpm.

- Aliquot the serum and store at -70°C until assayed.

2. Multiplex Immunoassay:

- Use a multiplex bead-based array system (e.g., Bio-Plex Human Cytokine 17-Plex panel on a Bio-Plex Suspension Array System).

- Following the manufacturer's protocol, incubate serum samples with antibody-conjugated magnetic beads.

- After washing, detect bound cytokines using a biotinylated detection antibody and a streptavidin-phycoerythrin conjugate.

- Measure fluorescence and calculate cytokine concentrations from standard curves.

3. Data Interpretation:

- Analyze the trajectory of key cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, IL-10) rather than single time-point measurements.

- Correlate persistent elevations or specific ratios of pro- to anti-inflammatory cytokines with the development of sepsis, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), or organ dysfunction [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating Post-Burn Systemic Complications

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application in Burn Research |

|---|---|

| Multiplex Cytokine Panels (e.g., Bio-Plex Human Cytokine Panels) | Simultaneous quantification of a broad spectrum of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, IL-10) from serum/plasma to profile the systemic inflammatory state [17]. |

| Electrical Impedance Analyzer | Quantitative assessment of red blood cell damage (a marker of systemic injury) by measuring the impedance characteristics of blood samples; used to calculate the proportion of heated red blood cells (HHCT) [19]. |

| Cell Culture Models (Endothelial Cells) | In vitro investigation of the pivotal role of endothelial cells in initiating inflammation, expressing adhesion molecules, recruiting immune cells, and regulating vascular permeability [6]. |

| DENVER2 Score Criteria | Validated clinical tool for prospective, daily monitoring of organ-specific function (cardiac, respiratory, hepatic, renal) in burn patients to define and track single or multiple organ failure [17]. |

| CompuCell3D Software | A flexible modeling environment for developing Glazier-Graner-Hogeweg (GGH) method-based agent-based models (ABM) to simulate spatial-temporal dynamics of the immune response to burns [6] [7]. |

Diagram 2: In Silico Research Workflow. This diagram outlines the iterative cycle of using computational models to generate and leverage biological data for predicting patient outcomes.

The link between local burn injury and remote organ dysfunction is mediated by a persistent, dysregulated systemic inflammatory response. Clinical risk factors such as large TBSA, inhalation injury, and early hypoalbuminemia provide actionable criteria for identifying high-risk patients. The integration of clinical monitoring with advanced research techniques—from electrical impedance spectroscopy to cytokine profiling—and sophisticated in silico models offers a powerful, multi-faceted approach to deconstruct this complexity. By applying these detailed protocols and computational frameworks, researchers and drug developers can gain deeper mechanistic insights and accelerate the development of therapies aimed at modulating the immune response to improve survival and long-term outcomes for burn patients.

Burn injuries trigger a complex and prolonged immune response that remains challenging to fully understand and treat through experimental methods alone. The massive, persistent inflammation can negatively affect wound healing and lead to multiple organ dysfunction [6]. The intricate spatial and temporal interactions between various immune cells, cytokines, and tissue components create a highly dynamic system that is difficult to analyze with traditional approaches. Computational modeling has emerged as a powerful tool to bridge this knowledge gap, providing a framework to simulate, analyze, and predict the behavior of the post-burn immune system in ways that laboratory experiments cannot [6] [7]. These in silico approaches enable researchers to uncover underlying mechanisms, test hypotheses in a controlled environment, and identify key intervention points for therapeutic development, ultimately accelerating progress in burn care.

Current Computational Approaches in Burn Research

Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) of Immune Dynamics

Agent-based modeling, particularly the Glazier-Graner-Hogeweg (GGH) method, also known as the Cellular Potts Model (CPM), has proven valuable for capturing the complexities of post-burn inflammation [6]. This approach simulates individual cells as independent agents that interact within defined biological compartments:

- Spatial Organization: Models typically separate the simulation domain into blood and tissue compartments, each containing solutes and cell agents [6]

- Cellular Agents: Include mast cells, neutrophils, and macrophages that are motile and exhibit chemotaxis based on concentration gradients of solutes [6]

- Molecular Components: Comprise pro-inflammatory cytokines, anti-inflammatory cytokines, and inflammation-triggering factors that diffuse throughout the domain [6]

Through simulations spanning days 0-4 post-burn, ABM has successfully identified the initial endothelial cell count as a pivotal parameter determining inflammation intensity and progression [6] [8]. This finding highlights how computational approaches can reveal key biological insights that might be overlooked in conventional studies.

Neural Network Surrogates for Enhanced Prediction

While ABMs provide detailed mechanistic insights, they are computationally intensive. Recent research has explored neural networks as surrogate models to approximate and forecast ABM simulation results:

- STA-LSTM (Spatio-Temporal Attention Long Short-Term Memory) generally performs best across statistical metrics for predicting cytokine concentrations [7]

- C-LSTM (Convolutional LSTM) significantly outperforms other networks in capturing spatial dependencies of cytokine concentrations [7]

- Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINN) produce a standard deviation that better reflects the expected variability in individual predictions [7]

These surrogate models enable rapid exploration of intervention strategies and parameter spaces that would be prohibitively time-consuming with full ABM simulations.

Quantitative Burn Assessment Through Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy

Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) provides a quantitative approach for burn injury detection by measuring the electrical impedance characteristics of blood with different volume proportions of red blood cells (RBCs) and heated red blood cells (HRBCs) [19]. The method employs a seven-parameter equivalent circuit to quantify the relationship between electrical properties and burn severity:

Table 1: Electrical Impedance Parameters for Burn Injury Assessment

| Parameter | Relationship with HHCT | Correlation Coefficient (R²) | Application in Burn Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaginary part of impedance (ZImt) | ZImt = -2.56HHCT - 2.01 | 0.96 | Primary parameter for injury degree detection |

| Plasma resistance (Rp) | Rp = -7.2HHCT + 3.91 | 0.96 | Verification parameter for injury severity |

| Characteristic frequency (fc) | Varies with HHCT | N/A | Identifies peak point Zt in Nyquist plots |

This approach demonstrates feasibility for rapid, quantitative burn injury detection through parameters ZImt and Rp, potentially enabling more efficient clinical treatment planning [19].

Precision Imaging and Predictive Modeling

Advanced imaging techniques combined with predictive modeling have revolutionized burn assessment accuracy:

- Adaptive Complex Independent Components Analysis (ACICA) and Reference Region (TBSA) methods enable precise estimation of burn depth and Total Body Surface Area with 96.7% accuracy using RNN models [20]

- Dynamic Contrast Enhancement (DCE) with GLCM-based texture analysis provides detailed tissue characterization, facilitating differentiation between various burn types [20]

- Deep neural network classification covers categories including healthy skin, superficial burn, superficial dermal burn, deep dermal burn, and full-thickness burn [20]

These technologies provide nuanced insights into burn severity, improving diagnostic accuracy and treatment planning beyond subjective clinical evaluations.

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Agent-Based Modeling of Acute Inflammation (Days 0-4 Post-Burn)

Objective: To simulate the spatial-temporal dynamics of immune cell interactions and cytokine signaling during the acute inflammatory phase following burn injury.

Workflow:

Key Parameters to Monitor:

- Initial endothelial cell count (critical determinant of inflammation intensity) [6]

- Chemotaxis threshold and chemoattractant levels [6]

- Neutrophil activation and macrophage polarization states [6]

- Pro- to anti-inflammatory cytokine ratios

Validation: Compare simulation outputs with experimental data from animal burn models, including cell counts and cytokine levels across the 4-day timeframe [6].

Protocol 2: Neural Network Surrogate Model Development

Objective: To create efficient neural network surrogates for predicting cytokine concentration dynamics in burn wounds.

Workflow:

Architecture Specifications:

- STA-LSTM: Implement spatial and temporal attention mechanisms for optimal statistical performance [7]

- C-LSTM: Use convolutional layers to capture spatial dependencies of cytokine distributions [7]

- PINN: Incorporate physical constraints to ensure biologically plausible predictions [7]

Evaluation Metrics: Mean Squared Error (MSE), R-squared, Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) [7].

Protocol 3: Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy for Burn Severity Quantification

Objective: To quantitatively assess burn injury severity through electrical impedance characteristics of blood components.

Table 2: Experimental Setup for EIS Burn Assessment

| Component | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Impedance Analyzer | IM7581 (Hioki E.E. Corporation) | Measure electrical impedance parameters |

| Fixture | 16092A (Agilent Technologies) | Secure cuvette during measurement |

| Cuvette | 12 mm × 12 mm × 45 mm with copper electrodes | Hold blood sample for testing |

| Electrodes | 10 mm × 20 mm with 2 mm distance | Enable electrical current application |

| Blood Sample Preparation | Swine blood with 3.28% trisodium citrate (1:9 ratio) | Prevent coagulation while maintaining physiological properties |

| Heating Protocol | 55°C for 1 hour in thermostatic water bath | Mimic burn injury effects on blood components |

| Centrifugation | 2000× g for 30 minutes at room temperature | Separate HRBCs, RBCs, and plasma |

Procedure:

- Prepare blood samples with varying proportions of HRBCs and RBCs (HCT + HHCT = 40%) [19]

- Measure impedance across frequency spectrum (100 kHz to 300 MHz) with applied current of 10 mA [19]

- Analyze Nyquist plots to identify characteristic frequency (fc) and peak point Zt (ZRet, ZImt) [19]

- Calculate HHCT using established linear relationships: ZImt = -2.56HHCT - 2.01 [19]

- Correlate HHCT with burn injury severity for clinical assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Burn Immunology

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CompuCell3D | Software platform for GGH/ABM simulations | Enables modeling of cell behaviors, solute diffusion, and chemotaxis in burn wounds [6] |

| Neural Network Frameworks | Implementation of surrogate models (TensorFlow, PyTorch) | Facilitates development of STA-LSTM, C-LSTM, and PINN architectures [7] |

| Impedance Analyzer | Measurement of electrical characteristics in blood | IM7581 system with frequency range 100 kHz-300 MHz for EIS burn assessment [19] |

| Dynamic Contrast Enhancement | Burn depth analysis via medical imaging | ACICA and RR methods for precise burn classification in transformed RGB to LUV images [20] |

| Animal Burn Model Data | Validation of computational predictions | Longitudinal cytokine levels and immune cell counts from rodent studies [6] |

| Seven-Parameter Equivalent Circuit | Quantitative analysis of EIS data | Electrical model correlating impedance parameters with HHCT for burn severity assessment [19] |

Signaling Pathways in Post-Burn Immune Response

The computational approaches outlined herein provide powerful methodologies for unraveling the complexity of post-burn immune responses. By integrating agent-based modeling, neural network surrogates, electrical impedance spectroscopy, and precision imaging, researchers can overcome traditional limitations in burn research. These protocols and application notes offer practical frameworks for implementing these cutting-edge computational techniques, accelerating the development of improved therapeutic interventions for burn patients. The continued refinement of these in silico methods promises to further bridge the knowledge gap between experimental observations and clinical applications in burn care.

A Technical Deep Dive into In Silico Modeling Frameworks for Burn Immunology

Within the context of in silico mechanistic modeling of the immune response to burn injuries, Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) provides a powerful computational framework for simulating complex biological systems. ABM breaks down a system into its constituent entities, treating each as an independent agent that makes decisions based on its local environment [21]. This paradigm is exceptionally well-suited for immunology because it enables the assignment of known cellular characteristics to each cell-agent, allowing researchers to simulate how mesoscopic entities' actions and interactions lead to macro-level events—a phenomenon known as emergent behavior [21].

The Glazier-Graner-Hogeweg (GGH) method, also known as the Cellular Potts Model (CPM), is a specific, versatile ABM formulation that allows for the representation of non-uniform cell shapes as agents in multi-cell systems [6]. Unlike simpler ABM approaches, the GGH framework can capture the spatial heterogeneity and complex cell-cell interactions characteristic of biological tissues. This capability is crucial for modeling the immune response to burn injuries, which involves a massive and prolonged acute inflammation involving intricate interactions between various cellular and molecular components [6]. The GGH method has recently been successfully deployed to investigate the dynamics of inflammation after burn injuries, identifying key factors such as the initial endothelial cell count that influence the acute inflammatory response [6] [8].

Key Quantitative Parameters for Simulating Post-Burn Immune Response

The development of a biologically relevant GGH model requires the careful definition of numerous parameters based on experimental data. The following tables summarize core cell behaviors and cytokine interactions identified as critical for simulating the first 0-4 days post-burn, a key period for acute inflammatory response [6] [22].

Table 1: Key Cellular Agents and Their Behaviors in Post-Burn Immune Response

| Cell Agent | Key Behaviors & Functions in Post-Burn Context | Temporal Dynamics (0-96h Post-Burn) |

|---|---|---|

| Endothelial Cells | Initiate inflammatory response; express adhesion molecules and chemokines; facilitate recruitment of immune cells; crucial for angiogenesis [6]. | Pivotal role in intensity and progression of acute inflammation (0-4 days) [6] [8]. |

| Neutrophils | Among first immune responders; remove necrotic tissue; release pro-inflammatory factors [22]. | Activated neutrophils (AN) increase (↑) then decline (); Resting neutrophils (RN) show a decrease (↓) by 48h [6]. |

| Macrophages | Differentiate into pro-inflammatory (M1) or "pro-healing" (M2) phenotypes; clear debris; regulate fibroblast behavior [6] [22]. | M1 macrophages increase (↑) around 48h then decline (); M2 macrophages show growth () from 72h [6]. |

| Fibroblasts | Migrate to wound site; key players in tissue regeneration and matrix deposition [6]. | Presence increases (↑) from 72h post-burn [6]. |

| Satellite Stem Cells (SSCs) | Activate, proliferate, and differentiate to repair damaged muscle fibers; behavior regulated by macrophages [22]. | Critical in the regeneration phase following initial inflammation [22]. |

Table 2: Critical Diffusing Factors and Their Roles in a Post-Burn GGH Model

| Diffusing Factor | Primary Function & Cellular Source | Impact on Burn Wound Healing Dynamics |

|---|---|---|

| Pro-inflammatory Cytokines (IL-8, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β) | Released by immune cells (e.g., neutrophils, M1 macrophages) post-burn; trigger and amplify immune response [6] [23]. | Drive acute inflammation; elevated levels associated with massive, prolonged inflammation post-burn [6]. |

| Anti-inflammatory Cytokines (IL-10) | Secreted by M2 macrophages and other cells; modulates inflammatory response [6] [22]. | Essential for transitioning from pro-inflammatory to pro-healing phase; prevents excessive tissue damage. |

| MCP-1 (Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1) | Chemokine recruiting monocytes/macrophages [22]. | Key for monocyte recruitment from blood to burn site; influences macrophage population dynamics. |

| TGF-β (Transforming Growth Factor Beta) | Secreted by macrophages, fibroblasts; regulates cell proliferation and differentiation [22]. | Plays a complex role in regeneration and fibrosis; potential target for therapeutic intervention. |

| HGF (Hepatocyte Growth Factor) | Involved in SSC activation and regeneration [22]. | Promotes muscle recovery; dynamics crucial for successful regeneration post-injury. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a GGH Model for Acute Burn Inflammation

This protocol outlines the steps to develop a GGH model simulating the immune response during the first 0-4 days post-burn, based on established methodologies [6] [22].

Pre-Simulation Setup and Model Configuration

- Software Selection: Implement the model using the CompuCell3D (CC3D) environment, a specialized, Python-based platform for CPM/GGH simulations (version 4.3.1 or higher) [22].

- Spatial Domain Definition: Create a 2D simulation lattice representing a cross-section of tissue and an adjacent blood compartment. A common size is 256x256 pixels, balancing computational cost and resolution [24].

- Agent Initialization: Populate the domain with agents based on pre-burn homeostasis. Stochastically induce injury by converting a defined region of healthy tissue to necrotic tissue to simulate the burn [22].

- Parameter Definition: Set the key parameters governing cell behaviors and interactions. The values below are illustrative and require calibration to specific experimental conditions.

Table 3: Core GGH Energy Hamiltonian Parameters (Illustrative)

| Parameter | Description | Example Value/Range |

|---|---|---|

J_cell,medium |

Contact energy between cell and medium. | 8.2 [24] |

J_cell,cell |

Contact energy between two cells. | 6 [24] |

λ_volume |

Constraint strength for maintaining target cell volume. | 5 [24] |

λ_surface |

Constraint strength for maintaining target cell surface. | 1 [24] |

λ_chemotaxis |

Strength of chemotactic response to a diffusing factor. | 2000 [24] |

Simulation Execution and Data Collection

- Monte Carlo Step (MCS) Loop: Run the simulation for a predefined number of MCS, where each step represents a unit of simulated time. The core algorithm involves:

- Pixel Copy Attempt: Randomly select a lattice pixel and a neighboring target pixel.

- Energy Change Calculation (

ΔH): Compute the change in the system's effective energy if the pixel copy were to occur. The Hamiltonian (H) includes terms for adhesion, volume constraint, surface constraint, and chemotaxis [24]:H = ∑[Adhesion Energy] + λ_volume(V_cell - V_target)² + λ_surface(S_cell - S_target)² + ∑[-λ_chemotaxis * (C_dest - C_source)] - Boltzmann Acceptance Function: Accept or reject the pixel copy based on the probability:

Pr = exp(-max(0, ΔH / B)), whereBrepresents the membrane fluctuation amplitude [24].

- Solute Diffusion: Simultaneously, at each MCS, update the concentration of every diffusing factor (cytokines, chemokines) across the lattice by solving a partial differential equation that includes diffusion, decay, and secretion terms:

∂c/∂t = D∇²c - kc + secretion[24]. - Data Logging: At regular intervals, record system-level data (e.g., cell counts, cytokine concentrations) and agent-level data (e.g., cell positions, state changes) for post-processing.

Model Calibration and Validation

- Calibration: Use parameter density estimation to refine parameters not available from literature by fitting model outputs to temporal biological datasets (e.g., cell counts from animal studies) [22]. The dataset from Mulder et al. (2022), which includes cytokine levels and immune cell counts from rodent burn models, is a key resource for this step [6].

- Validation: Qualitatively and quantitatively compare simulation outputs (e.g., dynamics of neutrophil infiltration, macrophage polarization, endothelial cell changes) against independent experimental data not used for calibration [6] [22]. For burn models, a critical validation is confirming that the simulated initial endothelial cell count directly correlates with the intensity and duration of the acute inflammatory response [6] [8].

Signaling and Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Core Signaling in Post-Burn Immune Response.

Diagram 2: GGH Model Development Workflow.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GGH Model Development

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in GGH Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| CompuCell3D (CC3D) | Software Platform | Primary simulation environment for developing, executing, and visualizing GGH/CPM models; handles core algorithms [22]. |

| Cell Studio | Software Platform / Framework | A hybrid platform for creating visualized, interactive 3D immune simulations; can use game engine technology [21]. |

| Parameter Density Estimation | Computational Method | An iterative protocol to calibrate unknown model parameters by fitting to temporal biological data [22]. |

| Animal Model Data (e.g., rodent burn studies) | Experimental Dataset | Provides critical, quantitative time-series data on cell counts and cytokine levels for model calibration and validation [6]. |

| Unity3D Game Engine | Software Platform | Can be used as a client for real-time 3D visualization and interaction with running simulations in a framework like Cell Studio [21]. |

| U-Net Convolutional Neural Network | Deep Learning Model | Can serve as a surrogate model to drastically accelerate simulation evaluation, e.g., predicting 100 MCS ahead [24]. |

In the field of in silico mechanistic modeling of the immune response to burn injuries, researchers face a significant computational challenge. High-fidelity models that simulate complex biological systems at a detailed level are often prohibitively slow for tasks requiring rapid iteration, such as parameter exploration, uncertainty quantification, or potential treatment screening. Surrogate modeling has emerged as a powerful solution, where data-driven models—particularly neural networks (NNs)—are trained to approximate the input-output behavior of complex mechanistic models with dramatically reduced computational cost [25] [26].

This paradigm is especially valuable in burn immunology, where the post-burn immune response involves intricate spatiotemporal interactions between numerous cell types, cytokines, and signaling molecules that evolve over time [6] [27]. Neural network surrogates enable researchers to accelerate simulations from hours to seconds while maintaining acceptable accuracy, thus enhancing both the speed and scalability of predictive modeling in burn research [26] [28].

Surrogate Model Applications in Burn Immunology and Related Fields

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Neural Network Surrogates Across Domains

| Application Domain | Base Model | Surrogate Model | Speed Increase | Accuracy vs. Base Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Wind Farm Wake Prediction | SOWFA (CFD) | Physics-Inspired NN + Autoencoder | Hours → Seconds | RMSE < 0.2 m/s (<2-5% error) | [26] |

| 3D Geotechnical Consolidation | Finite Element Method | Physics-Informed Neural Networks | N/A → <1 second | >98% accuracy | [28] |

| Dragonfly Network Simulation | PDES (CODES) | GNN + LLM (Smart) | 0.515 seconds inference | Outperformed statistical/ML baselines | [25] |

In burn immunology research, agent-based models (ABM) such as the Glazier-Graner-Hogeweg (GGH) method have been employed to simulate the dynamics of inflammation after burn injuries, capturing complexities including changes in cell counts and cytokine levels [6]. These models simulate individual cellular agents (e.g., mast cells, neutrophils, macrophages) and molecular solutes (e.g., pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines) across tissue and blood compartments, with cells exhibiting behaviors such as chemotaxis in response to concentration gradients [6] [8].

While these mechanistic models provide valuable insights, they can be computationally intensive for exploring the vast parameter space of biological conditions. Surrogate modeling approaches similar to those successfully applied in other fields (Table 1) could significantly accelerate burn immunology simulations, enabling rapid prediction of inflammation progression based on initial conditions such as endothelial cell count, a key parameter identified in recent research [6].

Protocol: Implementing NN Surrogates for Immune Response Prediction

Data Generation and Preparation Protocol

Table 2: Training Data Requirements for Effective Surrogate Models

| Data Type | Source | Key Parameters | Preprocessing Steps | Volume Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatiotemporal cell density data | GGH model simulations [6] | Cell counts (neutrophils, macrophages), cytokine concentrations | Spatial normalization, time-series alignment | 100+ simulation runs |

| Router performance data | PDES simulations [25] | Port-level features, application characteristics | Temporal alignment, graph structuring | Two dedicated datasets for training/validation |

| 3D Flow field data | SOWFA CFD simulations [26] | Velocity fields, turbulence parameters | Wind box decomposition, spatial encoding | Multiple farm layouts and conditions |

| Transcriptomic profiles | RNA-seq of burn-affected liver tissue [29] | Gene expression values, pathway activation | Log transformation, batch effect correction | Young/aged mice, multiple time points |

Procedure:

- Execute Base Model Simulations: Run multiple iterations of the high-fidelity GGH model [6] with varied initial conditions (endothelial cell count, chemotaxis thresholds, cytokine concentrations) to generate training data.

- Extract Spatial-Temporal Features: Capture cell density distributions and cytokine concentration profiles across both blood and tissue compartments at regular time intervals (e.g., hourly from day 0-4 post-burn).

- Implement Wind Box Decomposition (for spatial systems): For large or complex spatial domains, apply decomposition strategies that divide the simulation domain into smaller "wind boxes" or subregions, enabling modular training and enhanced scalability [26].

- Normalize and Partition Data: Apply min-max scaling or z-score normalization to numerical features, then split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets, ensuring temporal consistency in time-series data.

Neural Network Architecture Selection and Training

Materials:

- Python 3.8+ with TensorFlow 2.8+ or PyTorch 1.10+

- High-performance computing node with NVIDIA GPU (16GB+ VRAM)

- Custom data loaders for spatiotemporal biological data

Procedure:

- Architecture Selection:

- For spatial graph data (e.g., cell interactions across compartments): Implement Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) with message passing to capture neighborhood dependencies [25].

- For temporal sequences (e.g., cytokine level evolution): Integrate Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks or transformer-based temporal encoders [25].

- For incorporating physical constraints: Employ Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) that embed biological conservation laws directly into the loss function [28].

Model Implementation:

- Define encoder-decoder architecture with 3-5 hidden layers

- Incorporate skip connections to facilitate gradient flow

- Apply spatial pooling operations for multi-scale feature extraction

Training Configuration:

- Initialize weights using Glorot uniform initialization

- Set initial learning rate of 0.001 with exponential decay

- Use combined loss function: Mean Squared Error + Physical consistency term

- Implement early stopping with patience of 100 epochs

- Train for maximum 2000 epochs with batch size of 32-128

Diagram 1: Neural Network Surrogate Architecture for Burn Immune Response Prediction

Model Validation and Deployment Protocol

Procedure:

- Quantitative Validation:

- Compare surrogate predictions against held-out GGH simulation results using multiple metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and R² correlation coefficient.

- Establish accuracy thresholds: RMSE of cell counts <5% of dynamic range, R² >0.9 for cytokine trajectories.

Physical Consistency Checking:

- Verify that predictions obey biological conservation laws (e.g., mass balance of cells, energy constraints).

- Validate temporal monotonicity where biologically appropriate (e.g., non-decreasing scar tissue formation).

Uncertainty Quantification:

- Implement Monte Carlo dropout during inference to estimate prediction uncertainty.

- Flag predictions with high uncertainty for potential refinement through full simulation.

Deployment Optimization:

- Convert trained model to TensorFlow Lite or ONNX format for efficient inference.

- Implement caching mechanism for frequently queried initial conditions.

- Develop API interface for integration with existing research workflows.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Surrogate Modeling in Burn Immunology

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Platforms | GGH Model [6], CODES [25], SOWFA [26] | Generate high-fidelity training data through mechanistic simulation | Simulate post-burn immune cell dynamics across compartments |

| NN Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, JAX | Implement and train surrogate model architectures | Build GNN-LSTM hybrids for spatiotemporal prediction |

| Specialized Architectures | Graph Neural Networks [25], Physics-Informed NNs [28] | Capture spatial relationships and embed physical constraints | Enforce biological conservation laws in prediction tasks |

| Training Data Sources | Animal study data [6], Transcriptomics [29], Clinical immune parameters [27] | Provide experimental validation and system-specific parameters | Parameterize initial conditions from murine burn studies |

| Deployment Tools | TensorFlow Serving, ONNX Runtime, FastAPI | Enable production deployment and integration | Create web API for research team access to surrogate |

Application Notes for Burn Immunology Research

The implementation of NN surrogates for predicting post-burn immune responses requires special considerations specific to the biological domain:

Key Biological Parameters for Surrogate Modeling

- Initial endothelial cell count: Identified as a pivotal parameter influencing inflammation intensity and progression during acute inflammation (0-4 days post-burn) [6].

- Chemotaxis thresholds: Critical for accurate spatial prediction of immune cell migration toward inflammation sites.

- Cytokine dynamics: Pro-inflammatory (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) mediators that exhibit characteristic temporal patterns post-burn [27].

- Cell-type specific responses: Neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages (M1/M2 phenotypes), and fibroblasts each play distinct roles with different temporal dynamics [6].

Domain-Specific Adaptation Requirements

- Multi-scale modeling: Surrogates must bridge cellular-level events with tissue-level and systemic responses.

- Time-scale separation: Acute inflammatory processes (hours-days) versus healing and remodeling (weeks-months) require different modeling approaches.

- Aging considerations: Surrogate models may need age-specific parameters, as transcriptomic analyses reveal significantly different hepatic responses to burns in aged versus young mice [29].

Validation Against Experimental Data

Surrogate predictions should be validated against both in silico data and experimental observations:

- Immune cell infiltration patterns from histology

- Cytokine level measurements from blood/tissue samples

- Transcriptomic profiles from affected tissues [29]

- Clinical outcomes from burn patient studies [27]

Neural network surrogate models represent a powerful methodology for accelerating in silico research into the immune response following burn injuries. By implementing the protocols outlined in this document, researchers can develop accurate, efficient predictive tools that maintain the biological fidelity of complex mechanistic models while achieving speedups of several orders of magnitude. This approach enables previously infeasible large-scale parameter studies, uncertainty quantification, and potential real-time predictive capabilities that can advance our understanding of post-burn immunology and contribute to improved therapeutic strategies.

The immune response to burn injuries is a complex, multi-system process that involves intricate interactions between inflammatory mediators, immune cells, and metabolic pathways. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for improving patient outcomes, particularly because burns extend beyond the skin, inflicting damage on distant organs such as the liver and exacerbating poor outcomes in burn victims [29]. The mortality rate after burns in the elderly population is significantly higher than in any other age group, highlighting the need for precise mechanistic understanding [29].

Integrating transcriptomics and metabolomics provides a powerful framework for elucidating the underlying mechanisms of burn-induced pathology. While transcriptomics determines the functional response to burn injury and helps predict its master regulators, metabolomics provides a downstream, phenotype-proximal description of the biological processes [29]. This multi-omics approach enables researchers to move beyond correlative observations to build predictive in silico models that can simulate the dynamics of the immune response and identify potential therapeutic interventions.

This Application Note provides a detailed protocol for integrating transcriptomic and metabolomic data to construct mechanistic models of the immune response to burn injuries, with a specific focus on hepatic dysfunction. We summarize key quantitative findings, outline experimental and computational methodologies, and visualize critical signaling pathways to facilitate research in this area.

Key Omics Findings in Burn Injury and Related Inflammatory Conditions

Multi-omics studies have revealed consistent patterns of pathway dysregulation in burn injuries and other inflammatory conditions like sepsis. The table below summarizes key differentially expressed genes and metabolites identified in preclinical models.

Table 1: Key Omics Alterations in Inflammatory Injury Models

| Study Model | Differentially Expressed Genes | Altered Metabolites | Affected Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burn-Induced Liver Damage (Aged Mice) [29] | • Up: Derl3, Hyou1, Hspa5, Lcn2, S100a8/9• Down: Cyp2c29, Cyp2c38, Cyp2c54, Gsta3, Gsta4 |

Valine, Methionine, Tyrosine, Phenylalanine, Leucine [29] | • Protein processing in ER• IL-17 signaling• Chemical carcinogenesis• Steroid hormone biosynthesis• Xenobiotics metabolism by CYP450 |

| Agmatine-Treated Septic Liver Injury (Rats) [30] | 17 differentially expressed genes (e.g., involved in arginine/proline and arachidonic acid metabolism) | 26 significant metabolites | • Arginine and proline metabolism• Arachidonic acid metabolism• Linoleic acid metabolism• NF-κB and AMPK-PPARα signaling |

| Hypertension-Induced Hippocampal Injury (Rats) [31] | 103 differentially expressed genes | 56 significant metabolites (e.g., various amino acids) | Amino acid metabolism and related pathways |

These consistent findings across models provide a foundational dataset for building and validating in silico models of inflammatory organ damage.

Experimental Protocol for Generating Multi-Omics Data from Burn Models

This section details a standardized protocol for obtaining transcriptomic and metabolomic data from a murine burn model, as derived from published studies [29].

Animal Model and Burn Injury Induction

- Animal Subjects: Young and aged mice (e.g., 8-12 weeks for young; over 18 months for aged).

- Anesthesia: Anesthetize animals using intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (45 mg/kg) [30].

- Burn Procedure: Perform a standardized scald burn injury (e.g., ~30% total body surface area) on the shaved dorsal surface. Administer analgesic and fluid resuscitation post-procedure.

- Control Groups: Include sham-treated groups (anesthetized and shaved, but not burned).

- Sample Collection: At designated endpoint (e.g., 24 hours post-burn), euthanize animals and rapidly collect liver tissue. Snap-freeze tissue in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C until analysis.

Transcriptomic Profiling via RNA-Seq

- RNA Extraction: Homogenize ~30 mg of liver tissue. Extract total RNA using a commercial kit (e.g., Trizol reagent). Determine RNA purity and concentration using NanoDrop and Qubit RNA HS Assay Kit. Assess RNA integrity (RIN > 8.0) using an Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation system [30] [31].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Use Illumina-based protocols for library preparation (e.g., Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA). Perform paired-end sequencing (e.g., 2x150 bp) on an Illumina platform (e.g., Novaseq 6000) [31].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Use FastQC to assess raw read quality.

- Alignment: Align reads to the reference genome (e.g., mm10 for mouse) using STAR aligner.

- Quantification: Generate count data for genes using featureCounts.