Multi-Organ-on-a-Chip Systems: A New Paradigm for Immunotoxicity Assessment in Drug Development

This article explores the transformative role of multi-organ-on-a-chip (MOC) systems in advancing immunotoxicity studies.

Multi-Organ-on-a-Chip Systems: A New Paradigm for Immunotoxicity Assessment in Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of multi-organ-on-a-chip (MOC) systems in advancing immunotoxicity studies. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview of how these microphysiological systems replicate human organ interactions and immune responses to overcome the limitations of traditional 2D cultures and animal models. Covering foundational principles, methodological applications, troubleshooting, and validation strategies, the content synthesizes the latest technological breakthroughs and their practical implementation for predicting systemic immune-related adverse effects, aligning with modern regulatory shifts toward human-relevant testing methodologies.

The Foundation of MOC Systems for Immune Response Modeling

Defining Multi-Organ-on-a-Chip and Its Relevance to Immunotoxicity

Multi-organ-on-a-chip (multi-OoC) platforms are advanced microfluidic cell culture systems that integrate engineered or natural miniature tissues from multiple organs to mimic systemic physiological responses [1] [2]. These systems represent a significant evolution from single organ models by connecting separated organ chambers via microfluidic flow channels that emulate blood circulation, thereby enabling the study of complex inter-organ communication and its role in physiological and pathological processes [3] [4]. By supporting cross-organ communication, multi-OoC devices allow researchers to model multiorgan processes and systemic diseases, providing insights that would be lost using single-OoC models [1].

The relevance of multi-OoC technology to immunotoxicity assessment is particularly profound. Immunotoxicity—the adverse effects on the immune system resulting from exposure to chemical substances, drugs, or medical devices—has been challenging to evaluate using traditional models due to the systemic nature of immune responses [5] [6]. Multi-OoC platforms address this limitation by enabling the study of how substances breach biological barriers in one organ and trigger immune activation in distant organs, thereby providing a powerful tool for investigating systemic immunotoxicity [5].

Key Advantages for Immunotoxicity Assessment

Technical Capabilities

Multi-OoC platforms offer several distinct advantages over traditional models for immunotoxicity studies:

Recapitulation of Physiological Crosstalk: These systems simulate mutual and multiplex physiological communication between distant organs that may not be physically connected, known as multiorgan crosstalk [3]. This crosstalk is mediated by various factors including cells, soluble mediators (growth factors, cytokines), and cellular vesicles that regulate metabolic, inflammatory, and tissue repair processes in the body [3].

Integration of Immune Components: Advanced multi-OoC models incorporate key elements of the immune system, including Langerhans cells (skin), macrophages, and other immune cells, allowing for the study of complex immunotoxicological responses [5]. This capability is essential for investigating how exposure to sensitizing chemicals at one body site can lead to allergic responses such as contact dermatitis in distant organs [5].

Human-Relevance and Personalized Medicine Potential: By using human-derived cells, including patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), these platforms can model human-specific immune responses and interindividual variations in immunotoxicity [3] [7].

Long-Term Testing Capability: Recent advancements enable long-term cultivation (up to 4 weeks in some systems) of multiple tissues under dynamic flow conditions, allowing researchers to study chronic cellular reactions and delayed immune responses to pharmaceutical compounds and environmental toxicants [8] [4].

Comparison with Traditional Models

Table 1: Comparison of Model Systems for Immunotoxicity Assessment

| Feature | In vitro 2D Cell Culture | In vitro 3D Spheroid | In vivo Animal Models | Multi-OoC Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Relevance | Low | Medium | Variable (species differences) | High |

| Complex 3D Microenvironment | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Systemic Immune Response Capability | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Flow/Perfusion | No | Limited | Yes | Yes |

| Multi-organ Interactions | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Long-term Study Capability | <7 days | <7 days | >4 weeks | ~4 weeks |

| New Drug Modality Compatibility | Low | Medium | Low | Medium/High |

| Throughput | High | Medium | Low | Medium |

| Time to Result | Fast | Fast | Slow | Fast |

| High-content Data | Limited | Limited | Yes | Yes |

Experimental Platform: Investigating Systemic Immunotoxicity

Case Study: Nickel-Induced Systemic Immunotoxicity

A representative example of multi-OoC application in immunotoxicity assessment comes from a study investigating how oral exposure to metals can cause systemic toxicity leading to Langerhans cell activation in skin [5]. This research exemplifies the unique capabilities of multi-OoC platforms for studying systemic immunotoxicity mechanisms.

Experimental Design and Workflow

The study utilized a HUMIMIC Chip3plus platform (TissUse) to connect reconstructed human gingiva (RHG) and reconstructed human skin containing MUTZ-3-derived Langerhans cells (RHS-LC) through dynamic microfluidic flow [5]. The experimental workflow is illustrated below:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for nickel immunotoxicity study

Key Findings and Significance

This study demonstrated that nickel sulfate applied topically to reconstructed human gingiva resulted in increased activation of Langerhans cells in the distant skin model, observed through elevated mRNA levels of CD1a, CD207, HLA-DR, and CD86 in the dermal compartment [5]. Critically, this immune activation occurred without major histological changes in either tissue or significant cytokine release into the microfluidics compartment, highlighting the sensitivity of multi-OoC platforms in detecting subtle immunotoxic effects that might be missed in conventional models [5].

This approach provides a framework for studying systemic immunotoxicity where a chemical breaching one biological barrier (oral mucosa) triggers an immune response in a distant organ (skin), replicating clinical observations of systemic allergic responses to dental materials [5].

Technical Specifications of Representative Multi-OoC Platforms

Table 2: Technical Specifications of Commercial Multi-OoC Platforms

| Platform | Manufacturer | Key Features | Immunotoxicity Applications | Supported Organ Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HUMIMIC | TissUse | On-chip microfluidic channels connecting organ compartments; supports long-term dynamic co-culture | Gut-liver, liver-brain, liver-kidney crosstalk; systemic toxicity | Gut, liver, skin, brain, kidney |

| PhysioMimix Core | CN Bio | PDMS-free multi-chip plates; adjustable recirculating flow; up to 4-week culture | ADME toxicity; immune cell recruitment | Liver, intestine, pancreas, tumor |

| Omni | Axion BioSystems | Real-time electrophysiological monitoring; high-content imaging | Neural-immune interactions; chemotaxis studies | Brain, cardiac, neural spheroids |

| OrganoPlate | MIMETAS | Phaseguides for membrane-free co-cultures; pump-free perfusion | Barrier integrity; immune cell migration | Gut, blood-brain barrier, kidney |

| Emulate OOC | Emulate | Flexible membranes with mechanical stimulation (breathing, peristalsis) | Innate immune responses to pathogens | Lung, intestine, liver, brain |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol for Systemic Immunotoxicity Assessment

This protocol outlines the methodology for assessing systemic immunotoxicity using a multi-OoC platform, adapted from the nickel exposure study [5] with additional technical details for broader application.

Platform Preparation and Tissue Integration

- Microfluidic Chip Setup: Assemble the HUMIMIC Chip3plus according to manufacturer specifications, ensuring all microfluidic connections are secure and leak-free [5].

- Tissue Model Integration:

- Place reconstructed human gingiva (RHG) in the designated chamber

- Place reconstructed human skin with Langerhans cells (RHS-LC) in the adjacent chamber

- Verify tissue orientation to ensure proper epithelial alignment

- Initiate microfluidic perfusion at physiological flow rates (typical range: 0.1-10 μL/min)

- Stabilization Phase: Culture tissues under dynamic flow conditions for 24 hours to achieve stable culture parameters before experimental manipulation [5].

System Monitoring and Viability Assessment

- Metabolic Monitoring:

- Measure glucose consumption and lactate production every 12 hours

- Monitor lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release as a cytotoxicity indicator

- Use on-chip sensors or collect effluent for analysis

- Barrier Function Assessment:

- For epithelial barriers, measure transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) where applicable

- Assess barrier integrity using fluorescent tracers (e.g., FITC-dextran)

- Optimal Culture Parameters:

- Maintain glucose uptake between 0.5-1.0 mg/mL per 24 hours

- Ensure lactate production remains stable without significant increases

- Confirm LDH release <15% of total content indicating acceptable viability [5]

Compound Exposure and Endpoint Analysis

- Test Compound Application:

- Prepare test compounds in appropriate vehicles at physiologically relevant concentrations

- Apply topically to the RHG chamber for localized exposure

- Maintain circulation for 24 hours to allow systemic distribution

- Post-Exposure Incubation: Continue dynamic culture for additional 24 hours to observe delayed responses

- Endpoint Assessments:

- Histological Analysis: Fix and section tissues for H&E staining and morphological assessment

- Immune Cell Activation: Isolve RNA from dermal compartment for qPCR analysis of activation markers (CD1a, CD207, HLA-DR, CD86)

- Cytokine Profiling: Analyze effluent for cytokine release using multiplex immunoassays

- Cell Migration: Quantify Langerhans cell migration from epidermis to dermis [5]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Multi-OoC Immunotoxicity Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| HUMIMIC Chip3plus | Microfluidic platform for multi-tissue integration | Polysulfate or PDMS construction; 3+ tissue chambers; recirculating flow [5] |

| Reconstructed Human Gingiva (RHG) | Oral mucosa model for exposure site | Primary human keratinocytes/fibroblasts; air-liquid interface; 3D architecture [5] |

| Reconstructed Human Skin with Langerhans Cells (RHS-LC) | Target tissue for immune activation assessment | MUTZ-3-derived Langerhans cells; stratified epithelium; fibroblast-populated hydrogel [5] |

| MUTZ-3 Cell Line | Source of human Langerhans cells | CD34+ progenitor cell line; GM-CSF/TGF-β differentiation capability [5] |

| Cell Culture Media | Tissue maintenance and differentiation | Serum-free formulations; organ-specific growth factors; antibiotics [5] |

| Nickel Sulfate | Model immunotoxicant | >99% purity; prepared in aqueous solution; sterile filtered [5] |

| qPCR Reagents | Immune activation marker quantification | Primers for CD1a, CD207, HLA-DR, CD86; reverse transcription kit; SYBR Green master mix [5] |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Assay Kit | Cytotoxicity assessment | Colorimetric detection; compatible with microfluidic effluent [5] |

| Glucose/Lactate Assay Kits | Metabolic monitoring | Enzymatic assays; adapted for small volume samples [5] |

| Cytokine Multiplex Assay | Inflammatory response profiling | Human cytokine panels; high-sensitivity detection [5] |

| Ergothioneine-d3 | Ergothioneine-d3, MF:C9H15N3O2S, MW:232.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| KRAS inhibitor-6 | KRAS inhibitor-6, MF:C27H30ClF2N5O3, MW:546.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technological Implementation and Integration

Integration with Analytical Systems

The full potential of multi-OoC platforms for immunotoxicity assessment is realized through integration with advanced analytical systems:

- Real-time Biosensing: Incorporation of oxygen, pH, and metabolic sensors enables continuous monitoring of tissue viability and function during long-term experiments [4].

- Multi-omic Analysis: Advanced platforms support transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic analyses of both tissues and circulating factors, providing comprehensive mechanistic insights [1] [8].

- Microelectrode Arrays (MEAs): Integration with MEAs allows functional assessment of electrically active tissues (e.g., brain, heart) and their responses to immunotoxicants [4].

- High-Content Imaging: Compatibility with live-cell imaging and automated microscopy enables spatial and temporal analysis of immune cell behavior and tissue responses [9].

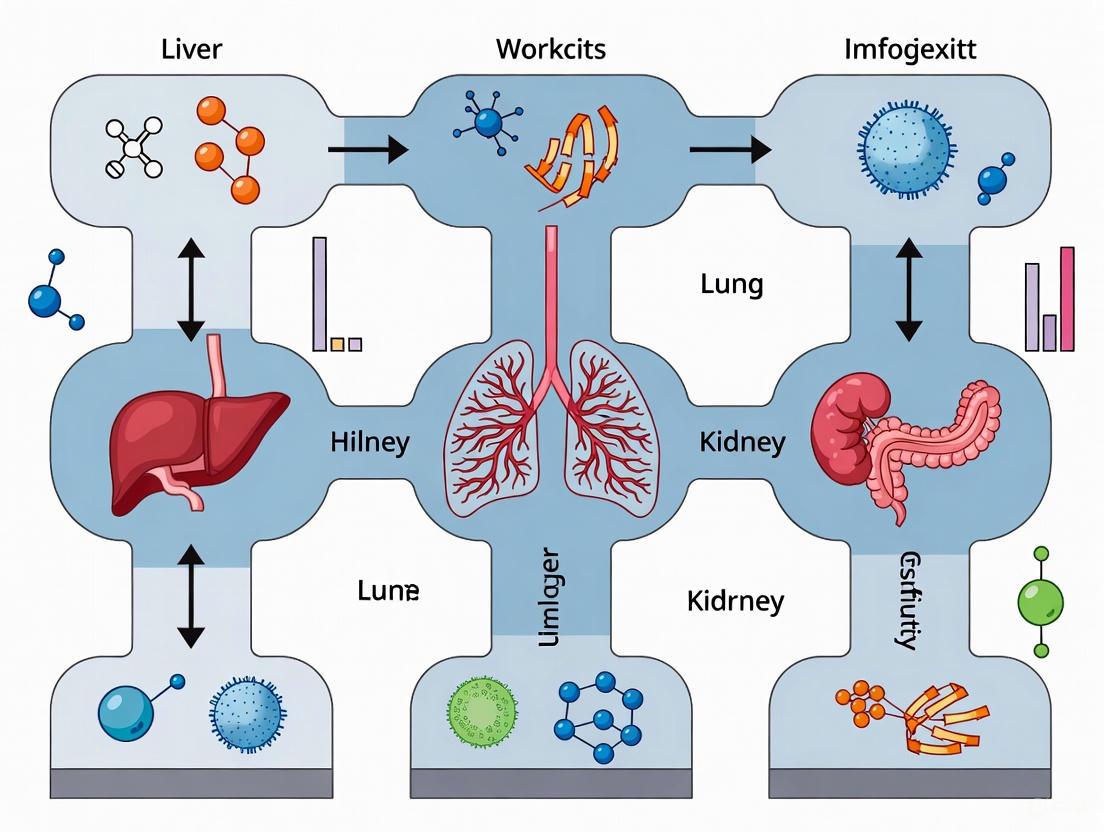

Inter-organ Communication in Immunotoxicity

The following diagram illustrates the key biological processes involved in systemic immunotoxicity that can be modeled using multi-OoC platforms:

Diagram 2: Key processes in systemic immunotoxicity

Multi-organ-on-a-chip technology represents a transformative approach for immunotoxicity assessment, addressing critical limitations of traditional models by enabling the study of systemic immune responses in a human-relevant context. The ability to model inter-organ communication and complex immune crosstalk provides unprecedented opportunities for understanding mechanisms of systemic immunotoxicity, screening potential immunotoxicants, and developing safer pharmaceuticals and consumer products.

As the field advances, key developments will focus on enhancing platform sophistication through integration of more complex immune components (lymph nodes, bone marrow), improving biosensing capabilities for real-time monitoring, and establishing standardized protocols for regulatory acceptance [1] [6] [4]. The ongoing transition toward personalized multi-OoC models using patient-derived cells will further advance our ability to predict individual-specific immunotoxic responses and support the development of precision medicine approaches.

With recent regulatory changes such as the FDA's phased plan to prioritize non-animal testing methods, multi-OoC platforms are poised to play an increasingly important role in safety assessment and drug development, potentially reducing reliance on animal models while improving the human predictivity of preclinical immunotoxicity evaluation [7].

Key Advantages Over Traditional 2D Cultures and Animal Models

Organ-on-a-Chip (OoC) technology represents a transformative approach in biomedical research, enabling the emulation of human organ structures and functions on microfluidic platforms [10]. For researchers focused on immunotoxicity studies within multi-organ systems, OoC technology provides a sophisticated and physiologically relevant in vitro model that bridges the critical gap between traditional 2D cell cultures and animal models. By replicating the dynamic, three-dimensional microenvironments of human tissues, these systems offer unprecedented insights into complex immunological interactions and systemic responses, thereby enhancing the predictive accuracy for human outcomes in drug development and toxicological assessment [11].

Key Advantages of Organ-on-Chip Technology

The transition from conventional models to OoC platforms is driven by several distinct advantages that address fundamental limitations of existing approaches. The table below summarizes the core benefits for immunotoxicity research.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Organ-on-Chip Models for Immunotoxicity Studies

| Feature | Traditional 2D Cultures | Animal Models | Organ-on-Chip Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Microenvironment | Static, flat cell growth; lacks tissue-specific architecture and mechanical cues [11]. | Species-specific physiology; may not accurately mimic human tissue barriers and immune responses [12] [13]. | Recreates 3D tissue architecture, dynamic fluid flow, and mechanical forces (e.g., breathing motions, peristalsis) [14] [11]. |

| Systemic Immunotoxicity Analysis | Limited to single cell types; cannot model inter-organ communication [5]. | Can observe systemic effects but with significant species-specific immunological differences [15]. | Enables interconnection of multiple organ models (e.g., gut-liver-skin) to study systemic immune activation and distant organ effects [10] [5]. |

| Predictive Value for Human Response | Poorly predictive of human in vivo organ-level responses and toxicity [11]. | Inefficient at predicting human responses; high failure rate in translating drug safety and efficacy [12] [15]. | Incorporates human cells; demonstrates higher relevance for predicting human drug responses and toxicity profiles [12] [14]. |

| Integration of Immune Components | Difficult to co-culture and maintain functional immune cells with organ-specific cells. | Possesses a full, but genetically distinct, immune system. | Capable of incorporating immune cells (e.g., Langerhans cells, PBMCs) into tissue models to study innate and adaptive immune responses [5] [16]. |

| Ethical & Regulatory Considerations | Ethically uncomplicated but biologically simplistic. | Raises significant ethical concerns; subject to strict regulations and high public scrutiny [15]. | Reduces reliance on animal testing; aligns with 3R principles (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) and modern regulatory shifts (e.g., FDA Modernization Act 2.0) [15] [13]. |

Beyond the comparative advantages, the quantitative challenges of current models further highlight the need for OoC technology. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has identified specific hurdles that limit wider adoption of OOCs, which also underscore the limitations of existing paradigms [12].

Table 2: Quantitative Challenges in Model Development and Implications

| Challenge | Quantitative/Severity Data | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Sourcing | Only 10-20% of purchased human cells are of high enough quality for OOC studies [12]. | Limits reproducibility and scalability of both advanced OoC and simpler 3D models. |

| Lack of Validation | Lack of sufficient benchmarks and validation studies against human clinical data [12]. | Hinders end-user (e.g., drug companies) ability to trust and adopt new models over conventional methods. |

| Data Sharing | Limited data sharing between competing companies and institutions [12]. | Slows collective learning and validation of the technology across the scientific community. |

Application Note: Investigating Systemic Immunotoxicity in a Multi-Organ Setting

Background and Objective

A critical challenge in immunotoxicology is understanding how a topical exposure in one part of the body can trigger an immune response in a distant organ. A 2022 study detailed a methodology to investigate this phenomenon, specifically how oral exposure to metals like nickel can lead to Langerhans cell activation in the skin, a event in allergic contact dermatitis [5]. This application note outlines the protocol for establishing a multi-organ-on-chip system to model this systemic immunotoxicity.

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the multi-organ immunotoxicity experiment.

Detailed Protocol

Objective: To assess systemic immunotoxicity by measuring Langerhans cell (LC) activation in a skin model following topical nickel application to a connected gingiva model within a multi-organ-chip [5].

Materials and Equipment

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| HUMIMIC Chip3plus | A microfluidic bioreactor platform enabling dynamic flow and connection of multiple tissue models in a closed circulatory system [5]. |

| Reconstructed Human Gingiva (RHG) | 3D model of human oral mucosa, consisting of a differentiated epithelium on a fibroblast-populated collagen hydrogel [5]. |

| Reconstructed Human Skin with Langerhans Cells (RHS-LC) | 3D skin model incorporating MUTZ-3-derived Langerhans cells into the epidermis, allowing for the study of LC maturation and migration [5]. |

| Nickel Sulfate (NiSOâ‚„) | A known skin sensitizer used as the model toxicant applied topically to the gingiva to simulate exposure from dental materials [5]. |

| Microfluidic Perfusion System | Provides dynamic, continuous flow of culture medium, mimicking blood circulation and enabling inter-organ communication [5] [11]. |

| Cell Culture Medium | Sustains the connected tissues under dynamic flow conditions; metabolites like glucose and lactate can be monitored for system health [5]. |

Methodology

Step 1: Chip Assembly and Tissue Integration 1.1. Incorporate the pre-formed Reconstructed Human Gingiva (RHG) and Reconstructed Human Skin with Langerhans Cells (RHS-LC) into the designated compartments of the HUMIMIC Chip3plus [5]. 1.2. Connect the tissue compartments via the microfluidic channels to establish a shared circulation.

Step 2: System Stabilization 2.1. Initiate dynamic flow of culture medium through the microfluidic circuit. 2.2. Culture the connected system for 24 hours under stable flow conditions to achieve equilibrium. Monitor system health by assessing glucose uptake, lactate production, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release in the effluent medium [5].

Step 3: Toxicant Exposure 3.1. After the stabilization period, apply a solution of nickel sulfate topically to the surface of the RHG (Reconstructed Human Gingiva) model. 3.2. Maintain the exposure for 24 hours under continuous dynamic flow.

Step 4: Post-Exposure Incubation 4.1. Remove the nickel source and continue perfusing the multi-organ system with fresh culture medium for an additional 24 hours. This allows for the dissemination of soluble factors and the manifestation of the immune response in the distant skin model [5].

Step 5: Endpoint Analysis Harvest the RHS-LC model and perform the following analyses: 5.1. Histology: Process tissues for histological staining (e.g., H&E) to assess major structural changes in both RHG and RHS-LC [5]. 5.2. Langerhans Cell Activation: * Migration Analysis: Identify and quantify LCs that have migrated from the epidermis into the dermal hydrogel (a key indicator of activation) [5]. * Gene Expression: Isulate RNA from the dermal compartment and analyze the mRNA expression levels of LC activation markers (e.g., CD1a, CD207, HLA-DR, and CD86) using quantitative PCR (qPCR) [5]. 5.3. Cytokine Profiling: Collect effluent medium and analyze for the presence of inflammatory cytokines using multiplex immunoassays (e.g., Luminex or ELISA). In the referenced study, no major cytokine release was detected, highlighting the specificity of the readout to LC activation [5].

Key Technical Considerations

- Quality Control: The stability of the dynamic culture is paramount. Consistently monitor metabolic parameters (glucose/lactate) throughout the experiment to ensure tissue viability and system integrity [5].

- Controls: Always include control chips that are treated with vehicle-only (e.g., PBS) instead of nickel sulfate to establish baseline levels of LC activation and gene expression.

- Reprodubility: Perform independent replicate experiments (e.g., n=3) with intra-experiment replicates to account for technical and biological donor variations [5].

Organ-on-Chip technology provides a paradigm shift for immunotoxicity research, moving beyond the static, single-type environment of 2D cultures and overcoming the species-specific limitations of animal models. The ability to interconnect organ models within a dynamic circulatory system, as demonstrated in the investigation of nickel-induced systemic immunotoxicity, allows scientists to dissect complex immunological cascades across multiple tissues. By offering a more human-relevant, controllable, and ethically advanced platform, OoC technology is poised to significantly improve the predictive power of preclinical safety assessments, thereby de-risking drug development and enhancing our understanding of human immunobiology.

Application Notes

This document details the application of a multi-organ-on-chip (MuOOC) platform for investigating systemic immunotoxicity triggered by topical exposure to chemical sensitizers. The platform is designed to model the remote activation of skin-based immune cells following exposure of a distant oral mucosal barrier, providing a novel in vitro method for studying complex adverse outcome pathways (AOPs) that cannot be recapitulated using single-organ models [5].

The specific case study involves connecting Reconstructed Human Gingiva (RHG) and Reconstructed Human Skin with integrated MUTZ-3-derived Langerhans cells (RHS-LC) within a microfluidic circulation. The primary readout is the activation of Langerhans cells in the skin compartment following topical application of nickel sulfate to the gingiva, mimicking systemic immune activation that can lead to conditions like allergic contact dermatitis [5].

Key Quantitative Parameters from the Model System

Table 1: Key quantitative parameters and culture conditions for the multi-organ-on-chip immunotoxicity study.

| Parameter | Detail / Value | Context / Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Organ Models | Reconstructed Human Gingiva (RHG), Reconstructed Human Skin with Langerhans Cells (RHS-LC) | Replicates human oral and skin barriers with integrated immune components [5]. |

| Chip System | HUMIMIC Chip3plus (TissUse GmbH) | Enables stable dynamic flow within a closed circuit with physiologically relevant shear stress [5]. |

| Total Culture Period | 72 hours | Standard duration for a complete experimental run [5]. |

| Dynamic Flow Stabilization | 24 hours | Initial period to achieve stable dynamic culture conditions before toxicant exposure [5]. |

| Toxicant Exposure Period | 24 hours | Duration of topical nickel sulfate application to the RHG [5]. |

| Post-Exposure Incubation | 24 hours | Time after exposure before analysis of Langerhans cell activation [5]. |

| Replication Strategy | Three independent experiments, each with an intra-experiment replicate | Assesses both donor and technical variations [5]. |

| Key Functional LC Markers | CD1a, CD207, HLA-DR, CD86 | mRNA levels measured in the dermal hydrogel to quantify LC activation and maturation [5]. |

Table 2: Key metabolic and cytotoxicity markers monitored in the microfluidic circuit.

| Marker | Measurement Purpose | Findings in Nickel Exposure |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose Uptake | Indicator of metabolic activity and tissue viability under dynamic flow [5]. | Stable levels indicated healthy culture conditions. |

| Lactate Production | Metabolic waste product; indicator of cellular stress and viability [5]. | Stable levels indicated healthy culture conditions. |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Release | Cytotoxicity marker; released upon cell damage [5]. | No major release, suggesting no significant cytotoxicity from nickel exposure. |

| Inflammatory Cytokine Release | Measures general immune activation and inflammatory response in the circuit [5]. | No major changes detected in the microfluidics compartment. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing the Multi-Organ-on-Chip Co-Culture

Objective: To integrate RHG and RHS-LC into the HUMIMIC Chip3plus and establish a stable, dynamic co-culture for 24 hours prior to toxicant exposure [5].

Materials:

- HUMIMIC Chip3plus system (TissUse GmbH)

- Prepared RHG tissue equivalents

- Prepared RHS-LC tissue equivalents

- Appropriate organ-specific maintenance medium

Procedure:

- Chip Priming: Flush all microfluidic channels of the HUMIMIC Chip3plus with culture medium to remove air bubbles and condition the system.

- Organoid Integration: Carefully transfer one RHG and one RHS-LC construct into their respective organ compartments on the chip.

- Initiate Dynamic Flow: Connect the chip to the perfusion system and initiate circulation at a physiologically low flow rate to minimize initial shear stress.

- Stabilization Culture: Maintain the connected system under dynamic flow conditions for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO₂.

- Viability Assessment: After the stabilization period, collect effluent from the microfluidic circuit and assess levels of glucose, lactate, and LDH to confirm stable metabolic activity and absence of significant cytotoxicity [5].

Protocol 2: Topical Toxicant Exposure and Assessment of Systemic Immunotoxicity

Objective: To apply a chemical sensitizer (nickel sulfate) to the RHG and quantify the subsequent activation of Langerhans cells in the distant RHS-LC construct [5].

Materials:

- Prepared nickel sulfate solution in an appropriate vehicle (e.g., water or PBS)

- RNA extraction kit

- qRT-PCR reagents and equipment

- Primers for CD1a, CD207, HLA-DR, and CD86

Procedure:

- Toxicant Application: After the 24-hour stabilization period, topically apply a defined volume and concentration of nickel sulfate solution directly onto the surface of the RHG tissue. Include vehicle-only controls in a parallel chip.

- Exposure Incubation: Continue the dynamic co-culture for an additional 24 hours post-application.

- Post-Exposure Incubation: Replace the circulating medium with fresh medium (without toxicant) and continue the dynamic culture for a further 24 hours.

- Tissue Harvest and Analysis:

- Dismantle the circuit and carefully separate the RHS-LC construct from the chip.

- Dissect the dermal compartment (hydrogel) from the epidermal compartment of the RHS-LC.

- Isolate total RNA from the dermal hydrogel.

- Perform qRT-PCR analysis to quantify the mRNA expression levels of the Langerhans cell activation markers CD1a, CD207, HLA-DR, and CD86 [5].

- Additional Endpoints: (Optional) Culture supernatants from the microfluidic circuit can be analyzed via multiplex immunoassays for cytokine release, and tissues can be processed for histology to assess structural integrity.

System Workflow and Signaling Visualization

Experimental Workflow for Immunotoxicity Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for replicating the multi-organ-on-chip immunotoxicity assay.

| Item | Function / Application in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| HUMIMIC Chip3plus (TissUse GmbH) | The core microfluidic bioreactor platform that provides a closed-circuit system with dynamic flow for connecting multiple organ models [5]. |

| Reconstructed Human Gingiva (RHG) | 3D tissue construct mimicking the oral mucosal barrier. Serves as the site for topical toxicant application in this model [5]. |

| Reconstructed Human Skin with MUTZ-LC (RHS-LC) | 3D skin equivalent with integrated, functional Langerhans cells. Acts as the distant target organ for monitoring systemic immunotoxicity [5]. |

| MUTZ-3 Cell Line | A human myeloid cell line that can be differentiated into Langerhans Cells (MUTZ-LC) for integration into 3D tissue models to introduce immune competence [5]. |

| Nickel Sulfate | A known metal sensitizer used as a model toxicant to trigger a systemic immune response from the oral mucosa to the skin [5]. |

| qRT-PCR Assays for CD1a, CD207, HLA-DR, CD86 | Key molecular tools for quantifying the activation (maturation) of Langerhans cells in the dermal compartment of the RHS-LC model [5]. |

| Metabolic Assay Kits (Glucose/Lactate/LDH) | Commercial colorimetric or fluorometric kits are essential for monitoring the metabolic state and viability of tissues in the microfluidic circuit during the stabilization and experimental phases [5]. |

| Trpc5-IN-2 | TRPC5-IN-2|Potent TRPC5 Channel Inhibitor|RUO |

| GLS1 Inhibitor-4 | GLS1 Inhibitor-4, MF:C29H27F3N10O2S2, MW:668.7 g/mol |

Mimicking Physiological Organ Crosstalk and Systemic Immunity

The study of immunotoxicity in drug development presents a significant challenge, as the immune system's effects are often systemic and involve complex crosstalk between multiple organs. Traditional in vitro models fail to recapitulate these dynamic interactions, leading to high failure rates in preclinical research. Multi-organ-on-a-chip (multi-OoC) platforms have emerged as a transformative technology that can mimic human physiological systems by supporting cross-organ communication through vascular perfusion, enabling the study of systemic immunity and immunotoxicity with unprecedented human relevance [1]. These microphysiological systems (MPS) provide a ground-breaking approach to evaluate the toxicity and therapeutic efficacy of compounds, including nanoparticles and biologics, by maintaining tissue-specific functions and enabling immune cell trafficking between connected organ compartments [17] [18]. This application note details protocols and methodologies for leveraging multi-OoC technology to advance immunotoxicity studies, with a focus on reproducing physiological organ crosstalk and systemic immune responses.

Multi-OoC Platform Configurations for Immunotoxicity Testing

Multi-OoC platforms are designed to simulate human physiological systems by connecting individual organ models within a circulating fluidic system. This configuration allows for the study of compound distribution, metabolism, and immune cell trafficking across different tissue barriers. Two primary architectural approaches have been developed: integrated body-on-a-chip devices and modular interconnected organ-specific modules [1].

Integrated Systems feature multiple organ chambers fabricated within a single microfluidic device, typically using soft lithography with materials like poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS). These systems benefit from controlled fluidic paths and reduced dead volumes but offer less flexibility for post-assay analysis.

Modular Systems consist of separate organ-specific modules that can be connected via tubing in various configurations to mimic different physiological scenarios. This approach, exemplified by platforms like the AVA Emulation System, offers greater flexibility for independent analysis of individual tissues and scalable experimental designs [18].

Advanced multi-OoC platforms now incorporate key elements of the immune, nervous, and vascular systems to better emulate human complexity in vivo [1]. The integration of patient-specific immune cells and tissue models further enables the development of personalized immunotoxicity profiles, potentially revolutionizing safety assessment in drug development.

Table 1: Comparison of Multi-OoC Platform Configurations for Immunotoxicity Studies

| Platform Type | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated Body-on-Chip | Single device with multiple organ chambers; Fabricated via soft lithography [9] | Controlled fluidic paths; Minimal dead volume; Reduced bubble formation | Limited post-assay flexibility; Fixed organ combinations | High-throughput screening; ADME studies [1] |

| Modular Interconnected | Separate organ modules connected via tubing; Self-contained incubator systems [18] | Flexible configurations; Independent tissue analysis; Scalable design | Potential for bubble accumulation; More complex fluidic control | Personalized immunotoxicity; Complex disease modeling [18] |

| Vascularized Systems | Endothelialized channels connecting organ compartments; Recirculating perfusion [1] | Physiological barrier function; Immune cell trafficking; Realistic compound distribution | Increased complexity of culture; Specialized media requirements | Immune cell recruitment studies; Nanoparticle transport [17] |

Quantitative Benefits of Multi-OoC Platforms in Preclinical Research

The implementation of multi-OoC technology in immunotoxicity assessment offers significant quantitative advantages over traditional models. These systems can dramatically reduce drug development timelines and costs while providing more human-relevant data. Recent advancements in high-throughput systems, such as the AVA Emulation System, have further enhanced these benefits by enabling parallel processing of up to 96 independent Organ-Chip samples in a single run [18].

The data generation capacity of modern multi-OoC platforms is particularly noteworthy for building robust datasets for machine learning applications. A typical 7-day experiment can generate >30,000 time-stamped data points from daily imaging and effluent assays, with post-takedown omics pushing the total into the millions [18]. This rich, multi-modal data provides a foundation for advanced computational modeling of immunotoxicity.

Table 2: Quantitative Benefits of Multi-OoC Platforms in Immunotoxicity Studies

| Parameter | Traditional Models | Multi-OoC Platforms | Improvement Factor | Impact on Immunotoxicity Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development Timeline | 2-5 years for preclinical | 6-18 months with OoC [17] | 60-70% reduction | Faster identification of immune-related toxicities |

| Compound Screening Cost | High (animal models) | Up to 50% reduction in consumables [18] | Significant cost savings | More extensive immunotoxicity screening within budget |

| Data Points per Experiment | Limited by endpoint assays | >30,000 in 7-day experiment [18] | Orders of magnitude increase | Comprehensive immune response profiling |

| Cell Requirement per Sample | Conventional culture volumes | Up to 50% fewer cells [18] | 2-fold improvement | Studies with limited primary human cells |

| Throughput | Low with complex co-cultures | 96 independent chips in single run [18] | High-throughput capability | Multiple immune cell conditions in parallel |

Protocol: Establishing a Multi-OoC Platform for Systemic Immunotoxicity Assessment

Materials and Equipment

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multi-OoC Immunotoxicity Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Chip-R1 Rigid Chips [18] | Low-drug-absorbing plastic consumables | Minimally adsorbing plastics; Shorter vascular channel for physiological shear stress |

| Chip-S1 Stretchable Chips [18] | Models requiring mechanical stimulation | Intestine-chip with peristalsis-like motions; Lung-chip with breathing motions |

| Chip A1 Accessible Chips [18] | Enhanced sampling capability | Easy access for tissue manipulation and analysis |

| Hydrogel Scaffolds [18] | 3D extracellular matrix support | RGD-modified hyaluronic acid hydrogel for enhanced cell resilience |

| Primary Human Cells | Patient-specific modeling | Hepatocytes, renal tubular cells, endothelial cells from human donors |

| iPSC-Derived Cells [9] | Disease modeling & personalized medicine | iPSC-derived endothelial cells and tissue-specific cells |

| Specialized Media | Tissue-specific support | Differentiation and maintenance media for multiple organ types |

Equipment

- AVA Emulation System or comparable multi-OoC platform [18]

- Zoë-CM2 Culture Module for continuous perfusion [18]

- Automated imaging system integrated with incubation

- Microfluidic perfusion controllers

- Laminar flow hood for sterile operations

- Incubator maintaining 37°C, 5% CO₂, and controlled humidity

Protocol Steps

Platform Assembly and Sterilization

- Chip Preparation: Select appropriate chip type based on experimental needs. For immunotoxicity studies with small molecules, use Chip-R1 rigid chips to minimize compound absorption [18]. For barrier function studies, use Chip-S1 stretchable chips.

- Sterilization: Sterilize chips and fluidic connections using appropriate methods (UV irradiation, autoclaving, or ethanol flushing) under sterile conditions.

- Matrix Coating: Coat chip chambers with appropriate extracellular matrix proteins (e.g., collagen IV, fibronectin) diluted in PBS at 100-200 µg/mL concentration. Incubate for 2 hours at 37°C or overnight at 4°C.

- Platform Priming: Assemble the multi-OoC system and prime with culture media, ensuring no bubble formation in microfluidic channels. Use degassed media and controlled flow rates (10-100 µL/hour depending on organ requirements) during priming.

Cell Seeding and Tissue Maturation

- Sequential Seeding: Seed endothelial cells in vascular channels first (1-2×10ⶠcells/mL), followed by tissue-specific cells in parenchymal channels after 4-24 hours.

- Establishment of Flow: Initiate perfusion 12-24 hours post-seeding, beginning with low flow rates (50 µL/hour) and gradually increasing to physiological levels (100-400 µL/hour) over 3-5 days.

- Tissue Maturation: Maintain tissues under flow conditions for 7-14 days to allow functional maturation, with media changes every 24-48 hours depending on metabolic activity.

- Quality Control Assessment: Verify tissue integrity and function through daily microscopy, transepithelial/transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurements where applicable, and effluent analysis for tissue-specific biomarkers.

Immunotoxicity Testing

- Compound Administration: Introduce test compounds through the vascular channel at clinically relevant concentrations. Include appropriate controls (vehicle alone).

- Immune Challenge: Introduce immune cells (PBMCs or specific immune cell populations) at physiological ratios (1:10 to 1:100 immune cells to parenchymal cells) through the vascular channel to assess recruitment and activation.

- Real-time Monitoring: Collect data through integrated sensors, daily imaging, and effluent sampling for cytokine analysis, metabolic markers, and tissue-specific biomarkers.

- Endpoint Analysis: At experiment conclusion, harvest tissues for histology, omics analysis (transcriptomics, proteomics), or other specialized assays to elucidate mechanisms of immunotoxicity.

Case Study: Lymph Node-Chip for Preclinical Immunotoxicity Prediction

Background and Rationale

Immunotoxicity remains a major challenge in drug development, particularly for novel modalities like biologics and immunomodulatory therapies. Pfizer has developed a Lymph Node-Chip capable of predicting antigen-specific immune responses, representing a significant advancement for preclinical immunotoxicity testing [18]. This model recapitulates key aspects of human immune responses, including antigen presentation, T-cell activation, and cytokine signaling, within a multi-OoC framework that enables systemic analysis.

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for establishing and utilizing the Lymph Node-Chip for immunotoxicity assessment:

Key Methodological Details

- Chip Configuration: Use a specialized chip design with dedicated compartments for antigen-presenting cells (dendritic cells) and T-cells, separated by microfluidic barriers that allow soluble factor exchange while controlling cell migration.

- Cell Sources: Utilize primary human dendritic cells derived from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors and autologous CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells from the same donor to maintain immune compatibility.

- Antigen Challenge: Introduce test compounds together with model antigens (e.g., ovalbumin, tetanus toxoid) or specific antigens relevant to the therapeutic area.

- Response Assessment: Monitor T-cell activation through:

- Effluent analysis for cytokine release (IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-6, TNF-α) at 6, 24, 48, and 72 hours

- Imaging of immune cell migration and cluster formation

- Expression of activation markers (CD69, CD25) via endpoint immunostaining

- Systemic Connection: For comprehensive immunotoxicity assessment, connect the Lymph Node-Chip to other organ models (liver, gut) to evaluate systemic effects of localized immune activation.

Data Interpretation and Analysis

The Lymph Node-Chip generates multi-parametric data that requires integrated analysis. Key parameters for immunotoxicity assessment include:

- Immunostimulation: Significant increase in T-cell activation markers and pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to controls may indicate undesirable immunostimulation.

- Immunosuppression: Failure to mount an appropriate immune response to challenge antigens may indicate immunosuppressive effects.

- Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) Risk: Specific cytokine profiles (particularly high IL-6 and IFN-γ) may predict potential for CRS, a serious adverse effect of many immunotherapies.

Advanced Protocol: Multi-OoC Platform for Nanomedicine Immunotoxicity

Background

Nanoparticles (NPs) have unique properties that make them promising for various biomedical applications, but their immunotoxicity profile is complex and often involves multiple organ systems [17]. Traditional in vitro and in vivo models struggle to predict NP-induced immunotoxicity due to species-specific differences in immune responses and the lack of integrated organ crosstalk. Multi-OoC platforms provide a human-relevant alternative for comprehensive NP immunotoxicity assessment.

Specialized Methodology for NP Testing

Platform Configuration

Establish a multi-OoC platform connecting liver, spleen, and lung models to assess NP immunotoxicity, as these organs represent primary sites of NP accumulation and immune processing.

- Liver-Chip: Incorporate hepatocytes and Kupffer cells (liver-resident macrophages) to model NP metabolism and initial immune recognition.

- Spleen-Chip: Include dendritic cells and B-cells to model antigen presentation and humoral immune responses to NPs.

- Lung-Chip: Feature airway epithelium and alveolar macrophages to assess pulmonary immune responses, particularly relevant for inhaled NPs.

NP Administration and Tracking

- Dosing Strategy: Introduce NPs through the vascular channel at concentrations reflecting expected human exposure (typically 0.1-100 µg/mL depending on application).

- Real-time Monitoring: Utilize label-free imaging techniques (phase contrast, hyperspectral imaging) to track NP distribution and accumulation in different organ compartments.

- Biodistribution Assessment: Quantify NP accumulation in different tissues through endpoint analysis using ICP-MS for metallic NPs or fluorescence measurement for labeled NPs.

Immunotoxicity Endpoints

- Innate Immune Activation: Monitor cytokine secretion (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6) and complement activation in effluent samples.

- Adaptive Immune Responses: Assess T-cell and B-cell activation in the spleen compartment through flow cytometry of harvested cells.

- Barrier Integrity: Measure TEER and permeability markers in epithelial barriers to assess NP-induced tissue damage.

- Oxidative Stress: Evaluate reactive oxygen species production in different tissue compartments using fluorescent probes.

The following diagram illustrates the inter-organ signaling pathways involved in NP-induced immunotoxicity within a multi-OoC system:

Data Analysis and Integration Framework

Multi-modal Data Integration

Modern multi-OoC platforms generate diverse data types that require sophisticated integration approaches. Establish a structured framework for data analysis that incorporates:

- High-content Imaging Data: Automated analysis of tissue morphology, immune cell infiltration, and cell viability using machine learning-based image segmentation.

- Effluent Biomarker Profiles: Time-course analysis of cytokines, metabolic markers, and tissue-specific enzymes using multiplex assays (Luminex, MSD) with appropriate normalization to tissue mass or DNA content.

- Functional Metrics: Integrate TEER measurements, metabolic activity (e.g., albumin production for liver models), and barrier integrity assessments.

- Endpoint Omics Data: Incorporate transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data from harvested tissues to elucidate mechanisms of immunotoxicity.

Cross-Species Correlation Analysis

For validation purposes, compare multi-OoC immunotoxicity data with historical in vivo results to establish correlation metrics. Focus on:

- Cytokine Storm Prediction: Develop predictive models for cytokine release syndrome based on early cytokine secretion patterns in multi-OoC platforms.

- Immune Cell Activation Thresholds: Establish quantitative relationships between compound concentration and immune cell activation across species.

- Organ-Specific Sensitivity: Compare relative sensitivity of different organ models to known immunotoxicants with established clinical profiles.

Table 4: Multi-OoC Data Correlation with Clinical Immunotoxicity Findings

| Immunotoxicity Endpoint | Multi-OoC Readout | Clinical Correlation | Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine Release Syndrome | Early IL-6 & IFN-γ surge in Lymph Node-Chip | CRS severity in patients | High correlation established for biologics [18] |

| Drug-Induced Autoimmunity | Loss of B-cell tolerance in Spleen-Chip | Autoantibody production | Potential for early detection; under validation |

| Hypersensitivity Reactions | Mast cell activation & histamine release | Clinical hypersensitivity incidence | Improved prediction over standard assays |

| Organ-Specific Inflammation | Tissue-specific cytokine patterns & immune infiltration | Target organ toxicity in clinical trials | Tissue-specific prediction enabling mitigation strategies |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Common Challenges and Solutions

- Bubble Formation: Degas all media and solutions at least 24 hours before use. Implement bubble traps in the fluidic path and establish priming protocols with gradual flow rate increases.

- Contamination Control: Implement strict sterile techniques during setup and regular antibiotic/antimycotic testing in media. Use integrated sensors for early detection of microbial contamination.

- Cell Viability Issues: Optimize seeding densities for each cell type and validate tissue-specific media formulations. Monitor nutrient and waste levels through frequent effluent analysis.

- Inconsistent Tissue Formation: Standardize cell source and passage number. Implement quality control checkpoints during tissue maturation using functional readouts rather than just temporal benchmarks.

Technical Optimization Guidelines

- Flow Rate Calibration: Determine optimal flow rates for each tissue type based on glucose consumption rates and tissue-specific shear stress requirements. Typical ranges are 50-100 µL/hour for barrier tissues and 100-400 µL/hour for vascularized tissues.

- Media Compatibility: Develop shared media formulations that support all connected tissues without compromising specific functions. Consider sequential media exposure strategies for tissues with incompatible requirements.

- Sampling Frequency Optimization: Balance data density with media volume constraints. For typical 100-200 µL recirculating volumes, limit sampling to 10-20% of total volume per day to maintain system stability.

- Endpoint Analysis Planning: Pre-plan harvest protocols for different analytical techniques (histology, omics, etc.) to ensure appropriate sample preservation and minimize experimental variability.

Implementing MOC Assays for Immunotoxicity Testing: Protocols and Case Studies

Multi-organ-on-chip (MOC) systems have emerged as transformative tools for investigating systemic toxicity and immunotoxicity, addressing critical limitations of traditional two-dimensional cell cultures and animal models. These microphysiological systems simulate human organ-level physiology by fluidically coupling microscale tissue models, enabling the recapitulation of complex organ-organ interactions and systemic drug responses. Within the context of immunotoxicity, MOCs provide a unique platform to study how drug candidates and environmental toxins trigger immune-mediated toxic responses across different organ systems, including bone marrow, liver, and skin. The integration of these three organ models is particularly valuable, as it captures the interplay between immune cell production (bone marrow), xenobiotic metabolism (liver), and external exposure (skin) – a triad crucial for comprehensive safety assessment in drug development.

Established MOC Platforms and Their Applications

Commercially Available MOC Systems

Table 1: Commercial Multi-Organ-on-Chip Platforms for Toxicity Testing

| Platform Name | Key Features | Supported Organ Models | Relevant Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| TissUse HUMIMIC | Microfluidic channels connecting organ compartments; supports long-term co-culture; option for automation [3] | Gut, liver, skin, kidney, brain, lymph node [3] | ADMET profiling, systemic toxicity, inter-organ crosstalk studies |

| Emulate Organ-Chip | Incorporates flexible membranes and mechanical stimulation (e.g., breathing, peristalsis) [3] | Lung, gut, liver, kidney, blood vessels | Barrier function studies, absorption, toxicity with biomechanical cues |

| CN Bio PhysioMimix | Liver-centric platform for long-term co-culture under flow [3] | Liver with other organ models (e.g., gut, kidney) | ADME studies, metabolism-dependent toxicity |

| MIMETAS OrganoPlate | Uses Phaseguides for membrane-free co-cultures; pump-free, automated perfusion [3] | Various tissue models, including skin and liver | High-throughput screening, barrier models, toxicity |

| InSphero Akura | Integrates 3D organoids under gravity-driven perfusion [3] | Liver, pancreas, tumor models with immune components | Scalable toxicity testing, immune-tumor interactions |

Key Technological Advancements in MOCs

Recent technological innovations have significantly enhanced the physiological relevance and application potential of MOC systems for toxicology studies. These include:

- Physiological Vascular Networks: Advanced MOC designs now incorporate vascular networks that replicate in vivo blood distribution among organs, enabling more realistic systemic exposure and toxicokinetic profiles [19].

- Functional Excretion Systems: Integration of excretory systems with micro-stirrers enhances the elimination of waste and toxic metabolites, maintaining long-term tissue viability and mimicking renal clearance [19].

- Integrated Immune Components: Incorporation of immune system elements, including lymph nodes and circulating immune cells, allows for modeling immunosuppressive effects, cytokine storms, and other immune-related toxicities [20] [21].

- Sensor Integration: Incorporation of biosensors for real-time monitoring of oxygen, pH, and tissue barrier integrity provides continuous data on tissue health and toxic responses [22].

- 3D Bioprinting: Utilization of 3D bioprinting enables precise fabrication of complex tissue architectures, including vascularized models, for more physiologically accurate toxicity assays [22].

Experimental Protocols for Systemic Toxicity Assessment

Protocol 1: Establishing a Tri-Culture MOC for Systemic Toxicity Screening

This protocol outlines the methodology for co-culturing bone marrow, liver, and skin models within an interconnected MOC platform to assess compound-induced systemic toxicity.

Principle: Fluidically coupling tissue models of bone marrow (immune cell production), liver (metabolism), and skin (primary exposure) enables the recapitulation of systemic toxicological pathways, including metabolic activation, immune-mediated responses, and multi-organ damage.

Materials:

- MOC Device: TissUse HUMIMIC Starter Chip or equivalent 2- or 3-organ platform [3]

- Cell Sources:

- Liver: Primary human hepatocytes (PHHs) or HepaRG cells for metabolically functional tissue [23]

- Bone Marrow: Primary human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) or immortalized cell lines (e.g., THP-1) [20]

- Skin: Commercially available full-thickness skin models (e.g., EpiDerm, MatTek) or primary keratinocytes/fibroblasts [3]

- Culture Media: A common circulation medium compatible with all three tissues, often a customized serum-free formulation to avoid undefined variables [19] [3]

- Characterization Reagents: ELISA kits for cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) and organ-specific biomarkers (e.g., Albumin for liver, LDH for general cytotoxicity)

Procedure:

- Tissue Model Preparation:

- Liver Spheroids: Generate 3D liver spheroids using PHHs in ultra-low attachment plates or on-chip. Differentiate HepaRG cells if used, following established protocols [23].

- Bone Marrow Culture: Seed HSPCs or bone marrow-derived cells into an appropriate 3D scaffold (e.g., collagen gel) within the designated organ chamber to support hematopoiesis and immune cell function.

- Skin Model: If using reconstructed human skin models, acclimate them according to the manufacturer's instructions before transferring to the MOC skin chamber.

MOC Assembly and Initiation:

- Load each tissue model into its respective chamber on the sterilized MOC device.

- Connect the organ chambers via the microfluidic network according to the manufacturer's instructions. A physiologically relevant configuration might sequence Skin → Liver → Bone Marrow to model topical exposure, hepatic metabolism, and systemic effects on hematopoiesis.

- Fill the system with the common circulation medium and initiate perfusion at a low flow rate (e.g., 1-10 µL/min) to allow tissue acclimation without excessive shear stress.

Maintenance and Dosing:

- Maintain the tri-culture under continuous perfusion at 37°C and 5% CO₂. Replace the common medium reservoir periodically (e.g., every 24-48 hours) [19].

- After a stabilization period (typically 3-7 days), administer the test compound. For skin-focused exposure, apply topically to the skin model. For systemic exposure, introduce the compound directly into the circulating medium.

- Maintain the MOC under treatment for a predetermined period (e.g., 7-14 days) to observe both acute and sub-chronic effects.

Endpoint Analysis:

- Viability and Cytotoxicity: Measure LDH release and ATP content in the medium and/or tissue lysates for each organ compartment.

- Functional Biomarkers:

- Liver: Quantify albumin and urea production in the medium. Assess CYP450 activity (e.g., using midazolam as a substrate) [23].

- Bone Marrow: Analyze immune cell population dynamics (e.g., CD4+/CD8+ T cells, monocytes) in the circulating medium and within the tissue compartment using flow cytometry.

- Skin: Measure Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) and assess tissue morphology via H&E staining.

- Systemic Inflammatory Response: Quantify a panel of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) in the circulating medium via multiplex ELISA.

- Histological Analysis: At the experiment terminus, fix and section tissues from each chamber for H&E and immunohistochemical staining to assess structural integrity and specific protein expression.

Protocol 2: Assessing Drug-Induced Liver-Bone Axis Toxicity

This protocol details the use of a simplified liver-bone marrow MOC to investigate toxicity along the liver-bone axis, relevant for drugs known to cause metabolic bone disease or suppress bone marrow function.

Principle: Co-culturing liver and bone marrow tissues allows for the study of how drug metabolites produced by the liver can directly impact bone marrow function and viability, modeling conditions like drug-induced osteoporosis or myelosuppression.

Materials:

- MOC Device: A two-organ MOC platform (e.g., CN Bio PhysioMimix or a custom PDMS chip) [3]

- Liver Model: Differentiated HepaRG spheroids [24] [23]

- Bone Marrow Model: THP-1 cells or primary human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hBM-MSCs) seeded in a 3D scaffold [24]

- Test Compound: Diclofenac (3-6 µM) or other drugs with known bone toxicity [24]

- Analysis Kits: ALT/AST assay kits, TRAP staining kit for osteoclast activity, Alizarin Red S for mineralization (if using hBM-MSCs)

Procedure:

- Establish Co-culture:

- Load liver spheroids and the 3D bone marrow construct into their respective chambers in the MOC.

- Connect the chambers and initiate perfusion with a suitable common medium (e.g., a 50:50 mix of liver- and bone-specific media may be optimized for co-culture [24]).

Compound Exposure:

- After stabilization, expose the system to the test compound (e.g., Diclofenac at 3-6 µM) via the circulating medium for up to 21 days to model chronic exposure [24].

Endpoint Analysis:

- Liver Toxicity: Monitor the culture medium for elevated levels of liver enzymes ALT and AST [23].

- Bone Marrow/Osteotoxicity:

- Osteoclast Activity: Quantify TRAP-positive multinucleated cells in the bone compartment. Co-culture with liver has been shown to significantly upregulate osteoclast activity following diclofenac exposure [24].

- Cytokine Analysis: Measure RANKL, OPG, and oxidative stress markers (e.g., ROS) in the medium, as these are implicated in drug-induced bone loss.

- Gene Expression: Analyze expression of osteogenic (e.g., Runx2) and osteoclastic (e.g., NFATc1) genes in the bone tissue via qPCR.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MOC-based Toxicity Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Human Hepatocytes (PHHs) | Gold standard for liver metabolism and toxicity studies; express full complement of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters [23] | Sourced from commercial providers (e.g., Discovery Life Sciences); require specialized media for long-term culture [23] |

| HepaRG Cell Line | Bipotent progenitor cell line that differentiates into hepatocyte-like and biliary-like cells; highly metabolic competence [24] [23] | Requires differentiation with DMSO; used for liver spheroid generation in toxicity models [24] |

| 3D Organotypic Skin Models | Reconstructed human epidermis or full-thickness skin models for topical exposure and barrier function assessment [3] | Commercially available (e.g., EpiDerm, MatTek); used for dermatotoxicity and absorption studies |

| THP-1 Cell Line | Human monocytic cell line; used as osteoclast precursors or to model innate immune responses in bone marrow compartments [24] | Can be differentiated into osteoclasts or macrophages using PMA or other inducing agents |

| Customized Common Media | Serum-free formulation designed to support the viability and functionality of multiple co-cultured tissue types simultaneously [19] [24] | Often requires empirical optimization (e.g., 50:50 mix of liver and bone media [24]) to maintain all tissues |

| Parylene C Coating | Biocompatible polymer coating for 3D-printed MOC devices; improves cell compatibility and prevents small molecule absorption [21] | Applied via gas-phase deposition onto 3D-printed chips to create a bioinert barrier [21] |

| Antibacterial agent 78 | Antibacterial agent 78, MF:C16H23N3S2, MW:321.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| KRAS inhibitor-8 | KRAS inhibitor-8, MF:C26H24ClF4N5O3, MW:565.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflow

Key Signaling Pathways in Systemic Immunotoxicity

The following diagram illustrates the proposed signaling pathways mediating immunotoxic crosstalk between liver, bone marrow, and skin in a tri-culture MOC system, particularly following drug exposure like diclofenac.

Diagram 1: Proposed Signaling Pathways in Systemic Immunotoxicity. This diagram illustrates how drug exposure can trigger metabolic and inflammatory responses in the liver, which subsequently drive toxicity in the bone marrow and skin, culminating in systemic immunotoxicity. Key mediators include reactive metabolites and pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Workflow for MOC Systemic Toxicity Assay

The following diagram outlines the generalized experimental workflow for conducting a systemic toxicity assessment using a multi-organ-on-chip platform.

Diagram 2: Workflow for MOC Systemic Toxicity Assay. This flowchart outlines the key stages of a standard MOC experiment, from tissue preparation through to data integration, highlighting the multi-parametric analysis required for a comprehensive toxicity assessment.

Nickel is a widespread environmental metal and a common cause of allergic contact dermatitis, affecting a significant portion of the population. The Systemic Nickel Allergy Syndrome (SNAS) describes a condition where ingested or systemically absorbed nickel can provoke or exacerbate cutaneous inflammation at sites distant from the exposure, such as the skin, even in the absence of local oral inflammation [5] [25]. This phenomenon presents a significant challenge for traditional single-tissue in vitro models, which cannot recapitulate the complex inter-organ communication required for systemic immune responses. Multi-organ-on-chip (MOC) technology represents a transformative approach for investigating such systemic immunotoxicity, allowing for the cultured interconnection of different tissue models under physiologically relevant dynamic flow conditions [5].

This application note details a specific MOC methodology developed to investigate how oral exposure to nickel, via a reconstructed human gingiva model, can initiate an immune cascade leading to the activation of Langerhans cells (LCs) in a physically separated reconstructed human skin model. This approach provides a novel framework for mechanistic toxicology studies, enabling the deconstruction of the key events in the Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) for sensitization across different organ systems, from chemical bioavailability to immune cell activation [5].

The core finding of this investigation was that topical application of nickel sulfate to the reconstructed human gingiva (RHG) in a dynamic MOC system resulted in the activation of Langerhans cells within the distant reconstructed human skin model (RHS-LC). This systemic effect was demonstrated without direct exposure of the skin model to the allergen [5].

Notably, the exposure did not cause major histological changes in either the gingiva or skin models, nor a significant release of most cytokines into the microfluidic circulation. The primary readout for systemic immunotoxicity was the observed LC activation, characterized by their increased migration from the epidermis to the dermal compartment and an upregulation of activation markers [5].

Table 1: Summary of Key Quantitative Data from the Gingiva-Skin MOC Experiment

| Parameter | Control Conditions | Post-Nickel Exposure | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture Stability | Stable glucose uptake, lactate production, and LDH release | Maintained stable levels | Biochemical analysis of microfluidic medium |

| Tissue Histology | Normal, stratified structure of RHG & RHS | No major histological changes | Histological analysis (H&E staining) |

| LC Migration | Baseline level of LC in dermis | Increased migration to dermal hydrogel | Quantitative PCR on dermal compartment |

| LC Activation Markers | Baseline mRNA expression | Increased mRNA levels of CD1a, CD207, HLA-DR, CD86 | Quantitative PCR on dermal compartment |

These findings align with clinical observations of systemic nickel allergy, where nickel sensitization and dietary nickel are considered a substantial trigger for the provocation and persistence of symptoms in patients with chronic allergic-like dermatitis syndromes [25]. The MOC model successfully captured this systemic effect, providing a platform to study the underlying mechanisms.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This protocol outlines the procedure for co-culturing reconstructed human gingiva (RHG) and reconstructed human skin with Langerhans cells (RHS-LC) in a HUMIMIC Chip3plus to investigate nickel-induced systemic immunotoxicity.

Materials and Reagents

- HUMIMIC Chip3plus (TissUse GmbH): A microfluidic bioreactor enabling a dynamic flow circuit with 4 independent organ niches.

- Reconstructed Human Gingiva (RHG): Comprises a differentiated gingiva epithelium on a fibroblast-populated collagen hydrogel.

- Reconstructed Human Skin with LC (RHS-LC): Contains integrated MUTZ-3-derived Langerhans cells within the epidermis on a fibroblast-populated hydrogel.

- MUTZ-3 Cell Line: A human myeloid cell line used as a source for deriving Langerhans cells.

- Culture Medium: Standard tissue maintenance medium for dynamic culture.

- Nickel Sulfate (NiSOâ‚„): Test compound, prepared in an appropriate vehicle (e.g., water or PBS).

- RNA Extraction Kit (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy).

- cDNA Synthesis Kit (e.g., Reverse Transcription System).

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR) reagents and primers for CD1a, CD207, HLA-DR, CD86, and housekeeping genes.

Methodologies

MOC Assembly and Dynamic Culture Initiation

- Tissue Integration: Carefully transfer the pre-formed RHG and RHS-LC tissues into their respective niches within the HUMIMIC Chip3plus.

- Circuit Connection: Connect the tissue compartments via the microfluidic channels to establish a common, dynamic flow of culture medium.

- Stabilization Culture: Initiate dynamic medium flow and culture the interconnected system for an initial 24-hour period. This allows the tissues to acclimate and achieve stable culture conditions under flow.

- Viability Assessment: Monitor the stability of the system by assessing glucose uptake, lactate production, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release into the microfluidic medium.

Nickel Exposure and Post-Exposure Culture

- Topical Application: After the 24-hour stabilization, apply a defined volume and concentration of nickel sulfate solution topically to the surface of the RHG tissue. The vehicle alone should be applied to control chips.

- Exposure Period: Maintain the chips under dynamic flow for a 24-hour exposure period.

- Post-Exposure Incubation: Carefully remove the nickel solution from the RHG surface and continue the dynamic co-culture of the connected tissues for an additional 24-hour period to allow for systemic signaling and immune cell activation.

Endpoint Analysis

- Tissue Viability and Histology: Process the RHG and RHS-LC tissues for standard histological analysis (e.g., H&E staining) to assess overall tissue structure and health.

- LC Migration and Activation Analysis:

- Separate the epidermis from the dermal hydrogel of the RHS-LC.

- Isolate total RNA from the dermal hydrogel compartment.

- Perform cDNA synthesis and subsequent qPCR analysis for Langerhans cell markers (CD1a, CD207) and activation markers (HLA-DR, CD86).

- The increase in mRNA of these markers in the dermis quantitatively reflects LC migration and activation.

- Cytokine Profiling: Collect microfluidic medium samples at the end of the experiment and analyze using a multiplex immunoassay (e.g., Luminex) to quantify the release of a panel of inflammatory cytokines.

Workflow Visualization

Underlying Molecular Mechanisms

Nickel exposure is known to exert diverse immunotoxic effects, and the systemic response observed in the MOC model can be understood through its impact on specific immune pathways and cells.

Immunotoxicity of Nickel

Excessive nickel exposure can inhibit the development of immune organs by inducing excessive apoptosis and inhibiting cell proliferation. It affects lymphocyte subpopulations, decreasing T and B lymphocytes, though the precise mechanisms require further elucidation [26]. Nickel's effect on immunoglobulins appears complex, with animal models showing suppressed IgA, IgG, and IgM levels, while some human studies have shown the opposite, indicating species-specific or context-dependent effects [26]. A key aspect of nickel's immunotoxicity is its dual role in cytokine regulation: it can inhibit cytokine production in non-inflammatory responses, but in the context of an inflammatory reaction, it significantly promotes cytokine production [26].

Nickel-Induced Inflammatory Signaling

A central mechanism for nickel-induced inflammation involves the activation of innate immune signaling pathways. Nickel ions can activate the Toll-like Receptor 4 (TLR4) pathway. This activation triggers two major downstream signaling cascades: the NF-κB pathway and the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathway (including JNK, ERK, and p38) [26]. These pathways are master regulators of inflammatory gene expression, leading to the increased production and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. This inflammatory milieu is critical for the maturation and activation of antigen-presenting cells like Langerhans cells.

Langerhans Cell Activation

In the skin model, Langerhans cells (LCs) reside in the epidermis as immune sentinels. Upon receiving inflammatory signals (either directly from nickel that has systemically circulated or indirectly via cytokine signaling from the gingiva), these LCs undergo maturation and activation. This process is characterized by:

- Upregulation of surface markers such as HLA-DR (Major Histocompatibility Complex class II) and co-stimulatory molecules like CD86, which are essential for efficient antigen presentation to T-cells [5].

- Migration from the epidermis into the dermal compartment, a crucial step for initiating an adaptive immune response [5]. The increased mRNA levels of CD1a, CD207, HLA-DR, and CD86 in the dermal compartment of the RHS-LC, as quantified by qPCR, are direct molecular correlates of this activation process [5].

Signaling Pathway Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Gingiva-Skin MOC Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HUMIMIC Chip3plus | Microfluidic bioreactor platform providing a dynamic flow circuit for interconnecting multiple tissue models. | Enables perfusion under physiologically relevant shear stress and tissue-to-fluid ratios [5]. |

| Reconstructed Human Gingiva (RHG) | Represents the oral mucosa barrier; site of topical nickel application to mimic oral exposure. | Comprises a differentiated epithelium on a fibroblast-populated collagen hydrogel [5]. |

| RHS with MUTZ-3 LC (RHS-LC) | Distant target organ model containing immune sentinels (Langerhans Cells) to monitor systemic effects. | MUTZ-3 derived LCs closely resemble their in vivo counterparts in function and phenotype [5]. |

| MUTZ-3 Cell Line | Source for generating human Langerhans cells (LCs) for integration into skin models. | Provides a reproducible and reliable source of functional LCs [5]. |

| Nickel Sulfate (NiSOâ‚„) | Model skin sensitizer and immunotoxicant used to induce systemic immune activation. | A soluble nickel compound; effects can be compared to other forms like NiO particulates [27]. |

| qPCR Assays | Quantitative measurement of LC activation and migration markers (CD1a, CD207, HLA-DR, CD86). | Key molecular endpoint for quantifying immunotoxicity in the dermal compartment [5]. |

| Cytokine Profiling Kits | Multiplexed measurement of cytokine release into the microfluidic medium as a systemic inflammation readout. | Can detect IL-1α, IL-8, and other analytes to assess inflammatory status [5] [27]. |

| KRAS inhibitor-13 | KRAS Inhibitor-13|High-Purity Research Compound | KRAS Inhibitor-13 is a small molecule targeting oncogenic KRAS mutations. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Sos1-IN-5 | Sos1-IN-5, MF:C26H31F3N4O5, MW:536.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The rapid development of organ-on-chip (OoC) technology has transformed the landscape of preclinical research, offering in vitro models that recapitulate key aspects of human physiology with remarkable fidelity [9]. These microphysiological systems (MPS) support miniature tissue models under dynamic flow conditions, enabling the study of organ-level responses in a controlled environment [1]. However, a significant limitation of many existing OoC models has been the inadequate incorporation of immune system components, which are crucial for understanding human physiology and pathology [28]. The immune system plays a fundamental role in nearly all disease processes, from cancer and metabolic disorders to infections and autoimmune conditions [28]. Without proper immune integration, these models provide an incomplete picture of human responses to drugs, toxins, and other stimuli.

Recent advances have begun to address this critical gap through the development of immunocompetent OoC models that incorporate various immune cell types, including tissue-resident macrophages and Langerhans cells (LCs) [29] [30]. These models are particularly valuable for systemic immunotoxicity studies, where communication between different organs and immune components is essential for accurate risk assessment [29]. This application note provides detailed protocols and methodologies for integrating key immune players—with special emphasis on Langerhans cells and macrophages—into multi-organ-on-chip platforms to advance immunotoxicity research and drug development.

Key Immune Players in Cutaneous and Systemic Immunity

Langerhans Cells: Sentinel Immune Cells of the Epidermis