Optimizing Antibody Validation for Flow Cytometry: A Complete Guide to Robust and Reproducible Results

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for optimizing antibody validation specifically for flow cytometry applications.

Optimizing Antibody Validation for Flow Cytometry: A Complete Guide to Robust and Reproducible Results

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for optimizing antibody validation specifically for flow cytometry applications. It covers the foundational importance of application-specific validation to overcome the reproducibility crisis, details rigorous methodological approaches including genetic strategies and multimodal verification, offers practical troubleshooting for common pitfalls like weak signals and high background, and explores advanced validation and comparative analysis for complex assays. The guide synthesizes established protocols with emerging trends to ensure data accuracy and reliability in both research and clinical diagnostics.

Why Application-Specific Antibody Validation is Critical for Flow Cytometry

FAQs: Antibody Validation and the Reproducibility Crisis

What is the antibody reproducibility crisis and what is its impact?

The antibody reproducibility crisis refers to the widespread finding that a significant proportion of research antibodies either do not recognize their intended target or are unselective, binding to multiple unrelated targets [1]. This has compromised the integrity of research findings, leading to:

- A colossal waste of resources: Irreproducible research is thought to cost $28 billion per year, with approximately $350 million attributed to the use of poorly characterized antibodies in the US alone. Others have estimated >$1 billion is wasted annually on poorly performing antibodies [1].

- Hampered drug development and scientific progress: The use of nonselective antibodies has contributed to the failure of many research projects and led entire scientific fields in the wrong direction [1].

- Erosion of trust: The crisis has damaged the reliability of scientific literature, with one survey revealing that at least 70% of scientists were unable to reproduce studies from other scientists, and 50% could not reproduce their own work [2].

Table 1: Key Statistics on the Antibody Reproducibility Crisis

| Metric | Statistic | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial antibodies failing basic characterization | ~50% | [3] |

| Annual US financial waste from bad antibodies | $350 million - $1.8 billion | [1] [3] |

| Researchers unable to reproduce others' studies | 70% | [2] |

| Researchers unable to reproduce their own work | 50% | [2] |

Why is application-specific validation for flow cytometry so critical?

Antibody performance is highly dependent on the specific application and sample preparation because the antigen's conformation can change dramatically between different assays [1] [4]. For example:

- Flow Cytometry vs. Western Blot: In flow cytometry, the antigen is typically in a more native, folded conformation, whereas in western blotting, the antigen is denatured and unfolded. An antibody that works in one may not work in the other [1].

- Sample Type and Protocol: The selectivity of an antibody is affected by the number of similar antigens present in the assay, which can vary substantially between cell types and tissues. Minor differences in protocols (e.g., fixation, permeabilization) can also significantly impact performance [1] [5].

What are the established pillars for antibody validation?

A consensus position known as the "five pillars" outlines specific methods for antibody validation [1] [4]. These are complementary approaches, and confidence increases with each pillar used.

Table 2: The Five Pillars of Antibody Validation

| Pillar | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Genetic Strategies | Use CRISPR-Cas9 knockout or RNAi knockdown to confirm loss of signal. [6] [1] | Gold standard; provides a clear negative control. [1] | Knockout may affect cell viability; knockdown can be partial or have off-target effects. [6] |

| 2. Orthogonal Strategies | Compare antibody staining to antibody-independent methods (e.g., RNAseq, mass spectrometry). [6] [1] | Useful where genetic strategies are not feasible. [1] | RNA expression does not always correlate with protein expression; requires multiple samples. [1] |

| 3. Independent Antibodies | Compare labeling patterns of antibodies targeting different epitopes of the same protein. [6] [1] | Supportive evidence for selectivity. [1] | Epitope information is often not disclosed, making true independence hard to confirm. [6] [1] |

| 4. Tagged Protein Expression | Transfert cells to overexpress a tagged target and confirm antibody co-localization. [6] [1] | Confirms ability to bind the target. [6] | Overexpression levels are non-physiological; cell line must lack endogenous expression. [6] |

| 5. Immunocapture with Mass Spectrometry | Immunoprecipitate the target and identify bound proteins via mass spectrometry. [1] | Directly identifies proteins bound by the antibody. [1] | Difficult to distinguish off-target binding from protein interaction partners. [1] |

What are common flow cytometry issues caused by poorly validated antibodies?

- High Background and/or Non-Specific Staining: This can be caused by antibodies binding to Fc receptors, over-titration, or the presence of dead cells [5] [7].

- Weak or No Signal: This may occur if the antibody is not selective for the target in the flow cytometry application, the epitope is damaged during fixation/permeabilization, or a dim fluorochrome is paired with a low-abundance target [5] [7].

- Inconsistent Results Between Lots or Experiments: This is a hallmark of poorly characterized polyclonal antibodies but can also affect monoclonal antibodies without rigorous manufacturing standards [1] [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Flow Cytometry Problems and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Flow Cytometry Issues

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background / Non-specific Staining | Fc receptor binding [5] [7] | Block cells with BSA, Fc receptor blocking reagents, or normal serum prior to staining. [5] [7] |

| Presence of dead cells [5] [7] | Use a viability dye (e.g., PI, 7-AAD, fixable viability dyes) to gate out dead cells during analysis. [5] [7] | |

| Antibody concentration too high (over-titration) [5] | Titrate the antibody to find the optimal concentration. Follow manufacturer-recommended dilutions. [5] | |

| Weak or No Signal | Antibody not validated for flow cytometry [8] [5] | Check the manufacturer's datasheet to ensure the antibody is validated for flow cytometry. |

| Low antigen expression paired with a dim fluorochrome [5] [7] | Use the brightest fluorochrome (e.g., PE) for the lowest density targets. [5] | |

| Inappropriate fixation/permeabilization [5] [7] | Optimize fixation and permeabilization for your target. For intracellular targets, ensure protocols are appropriate for the target's location. [5] [7] | |

| Inconsistent Results Day-to-Day | Lot-to-lot variability of the antibody [1] [3] | Switch to recombinant antibodies, which offer superior lot-to-lot consistency. [1] [4] |

| Suboptimal instrument settings or calibration [7] | Use calibration beads to standardize instrument performance. Ensure consistent laser and PMT settings. [7] |

Experimental Protocols for Antibody Validation in Flow Cytometry

Protocol 1: Validation Using Genetic Knockout/Knockdown

This protocol uses the first pillar of validation (genetic strategies) to confirm antibody specificity [6] [1].

- Cell Line Selection: Choose a cell line that expresses your target protein endogenously and is amenable to genetic modification.

- Generate Knockout/Knockdown:

- Confirm Knockout/Knockdown: Confirm reduced expression at the RNA level by RT-qPCR and/or at the protein level using an orthogonal method [6].

- Flow Cytometry Staining and Analysis:

- Stain both the wild-type (control) and knockout/knockdown cells with the antibody under validation.

- Include appropriate controls (unstained, isotype control).

- A selective antibody will show a significant reduction or complete loss of signal in the knockout/knockdown cells compared to the control.

Protocol 2: Validation Using Orthogonal Correlation with mRNA Expression

This protocol correlates flow cytometry data with mRNA expression data across multiple cell types, aligning with the second pillar of validation [6] [1].

- Sample Selection: Select a minimum of 3-5 different cell lines or primary cell types with known, varying expression levels of your target mRNA (e.g., from public RNAseq databases).

- Cell Staining: Stain a fixed number of cells from each cell type with the antibody under validation using a standardized flow cytometry protocol. Cell tracker dyes can be used to mix cell types and stain them in the same tube to minimize technical variation [6].

- Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Acquire flow cytometry data for all samples, recording the Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) for the target signal.

- Plot the MFI for each cell type against its known mRNA expression level.

- A selective antibody will show a strong, statistically significant positive correlation between MFI and mRNA expression levels across the different cell types [6].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Antibody Validation

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Validation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Cell Lines | Provides a definitive negative control to test antibody specificity by completely removing the target protein. [1] | Ensure the knockout is complete and verify the absence of the protein with a validated method. |

| Recombinant Antibodies | Defined sequence and renewable production ensure superior lot-to-lot consistency, directly addressing reproducibility. [1] [4] | Increasingly available from major vendors. Prefer over traditional hybridoma-derived monoclonals for critical applications. |

| siRNA/shRNA | Used for transient or stable knockdown of target expression when knockout is not feasible. [6] | Can result in only partial knockdown; confirm efficiency at RNA and protein level and watch for off-target effects. [6] |

| Cell Viability Dyes | Critical for identifying and gating out dead cells, which exhibit high non-specific antibody binding, reducing background. [5] [7] | Use standard dyes (PI, 7-AAD) for live-cell staining; use fixable viability dyes for intracellular staining protocols. [5] |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagents | Blocks non-specific binding of antibodies to Fc receptors on immune cells, a major source of high background. [5] [7] | Essential when working with primary immune cells like PBMCs. |

| HLDA Workshop Approved Clones | Antibodies characterized by the Human Cell Differentiation Molecules (HCDM) workshops provide an independent, community-vetted resource. [6] | A reliable starting point for well-characterized antibodies against CD markers on human leukocytes. |

In flow cytometry research, antibody validation is a critical process to ensure that the data you generate is accurate, reliable, and interpretable. Validation confirms that an antibody specifically recognizes its intended target, can selectively distinguish it within a complex mixture, is sensitive enough to detect low expression levels, and delivers consistent results across experiments [9]. For researchers and drug development professionals, rigorous validation is not optional—it is fundamental to achieving reproducible findings and making sound scientific conclusions. This guide provides troubleshooting and best practices for establishing these four pillars in your flow cytometry workflow.

The Four Pillars of Antibody Validation

Specificity

Specificity is the ability of an antibody to bind exclusively to its target antigen and not to other, non-target molecules. A specific antibody will have a high degree of fit between its paratope and the intended epitope on the target protein [9].

Key Validation Methods:

- Genetic Strategies (Knockout/Knockdown): This is one of the most trusted methods. It involves using CRISPR/Cas9 or RNAi to create cell lines where the target gene is deleted (knockout) or its expression is significantly reduced (knockdown). A specific antibody will show a loss or major reduction of signal in the knockout/knockdown sample compared to the wild-type control [10] [11] [9].

- Orthogonal Strategies: This approach uses a non-antibody-based method (e.g., mass spectrometry) to quantify the target protein and then correlates these results with the flow cytometry data to confirm the antibody's specificity [12] [9].

- Independent Antibody Strategies: Using two or more independent antibodies that recognize non-overlapping epitopes on the same target protein can build confidence. Correlation between the signals from the different antibodies supports the specificity of each [9].

Selectivity

Selectivity describes how well an antibody binds to its intended target antigen within a complex mixture, such as a whole cell lysate or a heterogeneous cell population, showing little cross-reactivity with other antigens [9]. In flow cytometry, this means the antibody should only stain cell populations known to express the target antigen.

Key Validation Methods:

- Cell Panel Profiling: Test the antibody on a panel of cell lines or primary cells with well-characterized expression profiles of the target protein. The flow cytometry staining should correlate with known expression patterns.

- Peptide Blocking: Pre-incubate the antibody with an excess of the specific peptide corresponding to the epitope it recognizes. If the signal is significantly reduced or abolished in the subsequent flow cytometry experiment, it indicates that the antibody binding is selective for that epitope [11].

Sensitivity

Sensitivity is the ability of an antibody to detect low levels of the target antigen. It is influenced by the antibody's affinity, which is the strength of the interaction between a single antibody paratope and its epitope [9]. A high-affinity antibody will bind more antigen in a shorter time and is essential for detecting low-abundance targets.

Key Validation Methods:

- Titration: Perform a titration curve by using a series of antibody concentrations on cells expressing the target. The optimal concentration is one that provides the best signal-to-noise ratio (clear positive staining with minimal background), not necessarily the strongest signal.

- Use of Low-Expressing Cell Lines: Validate the antibody on cell lines known to have low expression levels of the target protein to ensure it can reliably distinguish positive events from negative ones.

Reproducibility

Reproducibility ensures that the validation data and experimental results can be consistently replicated over time and across different operators, instruments, and lots of antibodies [9]. Batch-to-batch variability is a significant challenge, particularly with polyclonal antibodies [10].

Key Validation Methods:

- Standardized Protocols: Implement and meticulously follow standardized operating procedures (SOPs) for sample preparation, staining, and instrument operation [13].

- Instrument Calibration: Regularly calibrate the flow cytometer using standardized beads to ensure day-to-day performance consistency [13].

- Lot-to-Lot Testing: When a new lot of antibody is received, compare its performance directly with the previous lot using a standard sample to check for consistency. Where possible, use recombinant antibodies, which offer superior reproducibility due to their defined genetic sequence [10].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My antibody works perfectly in Western blot, but fails in flow cytometry. Why? Antibody performance is highly application-specific. Western blot uses denatured proteins, so antibodies recognize linear epitopes. Flow cytometry typically requires antibodies to bind to conformational epitopes on proteins in their native state. An antibody validated for one application is not guaranteed to work in another [14] [15] [10]. Always check the datasheet for flow cytometry validation.

Q2: How can I reduce background noise and high fluorescence in my negative control?

- Titrate Your Antibody: The most common cause is antibody overuse. Perform a titration to find the optimal concentration.

- Check Fc Receptor Blocking: For some cell types (e.g., immune cells), use an Fc receptor blocking reagent to prevent non-specific antibody binding.

- Include Appropriate Controls: Always use both unstained cells and an isotype control to set your negative gates correctly.

Q3: What is the best negative control for demonstrating specificity in flow cytometry? A genetic knockout (KO) cell line for your target protein is considered the gold standard negative control. The absence of signal in the KO sample, compared to a wild-type control, is the strongest evidence of specificity [10] [9]. If a KO line is unavailable, a knockdown (KD) or known negative cell line can be used.

Q4: I see a lot of batch-to-batch variability with my polyclonal antibodies. What can I do? Switch to monoclonal or, ideally, recombinant antibodies. Recombinant antibodies are produced from a known DNA sequence, which eliminates biological variability and ensures exceptional batch-to-batch consistency [10].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Signal | Antibody concentration too low; target not expressed; incorrect laser/fluorophore setup. | Titrate antibody; use a positive control cell line; check cytometer configuration. |

| High Background | Antibody concentration too high; insufficient washing; non-specific Fc binding. | Titrate antibody; increase wash steps; use Fc block. |

| Poor Reproducibility | Variable sample preparation; instrument drift; different antibody lots. | Standardize protocol; perform daily calibration; test new antibody lots. |

| Unexpected Staining Pattern | Antibody cross-reactivity; protein expression in unknown lineage. | Validate with KO control; check literature for known expression. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Specificity Using Knockout Cell Lines

This protocol provides a robust method to confirm antibody specificity.

- Obtain Cells: Acquire wild-type (WT) and target gene knockout (KO) cell lines.

- Prepare Single-Cell Suspension: Ensure cells are in a single-cell suspension, free from clumps and debris [13].

- Stain Cells: Aliquot cells into tubes. Stain both WT and KO cells with the validated antibody concentration and the appropriate isotype control. Include a viability dye to exclude dead cells.

- Incubate and Wash: Follow standard staining procedures (incubation, washing, resuspension in buffer) [13].

- Acquire Data: Run samples on the flow cytometer.

- Analyze Data: The antibody is specific if a clear positive population is seen in the WT cells and this population is absent in the KO cells, which should look identical to the isotype control.

Protocol 2: Antibody Titration for Optimal Sensitivity

Titration is crucial for maximizing signal-to-noise ratio.

- Prepare Cells: Aliquot a sufficient number of positive control cells (known to express the target) into multiple tubes.

- Dilution Series: Prepare a series of antibody dilutions (e.g., 0.5x, 1x, 2x, 5x the manufacturer's recommended concentration).

- Stain: Add each antibody dilution to a separate tube of cells, along with unstained and isotype controls.

- Acquire and Analyze: Run all samples and plot the Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) of the positive population against the antibody concentration. The optimal concentration is typically at the plateau just before the MFI stops increasing, ensuring sensitivity without wasting reagent or increasing background.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions essential for antibody validation in flow cytometry.

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Antibodies specifically verified for flow cytometry that bind to the target of interest. Choose clones with validation data (e.g., KO) in your application [14] [10]. |

| Isotype Controls | Antibodies with no specific target, matching the host species and isotope of the primary antibody. Critical for distinguishing non-specific background binding from specific signal. |

| Cell Viability Dye | A dye to exclude dead cells from analysis, as dead cells often bind antibodies non-specifically, leading to inaccurate results. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent | Blocks Fc receptors on certain cell types (e.g., macrophages, dendritic cells) to prevent non-specific antibody binding, reducing background. |

| Compensation Beads | Uniform beads that bind antibodies, used to calculate spectral overlap (compensation) between fluorochromes, which is essential for accurate multi-color experiments [13]. |

| Standardization/Calibration Beads | Beads with defined fluorescence properties used to calibrate the flow cytometer, ensuring consistent performance and reproducibility over time [13]. |

| Knockout (KO) Cell Line | A genetically engineered cell line lacking the target gene. Serves as the best negative control for demonstrating antibody specificity [9]. |

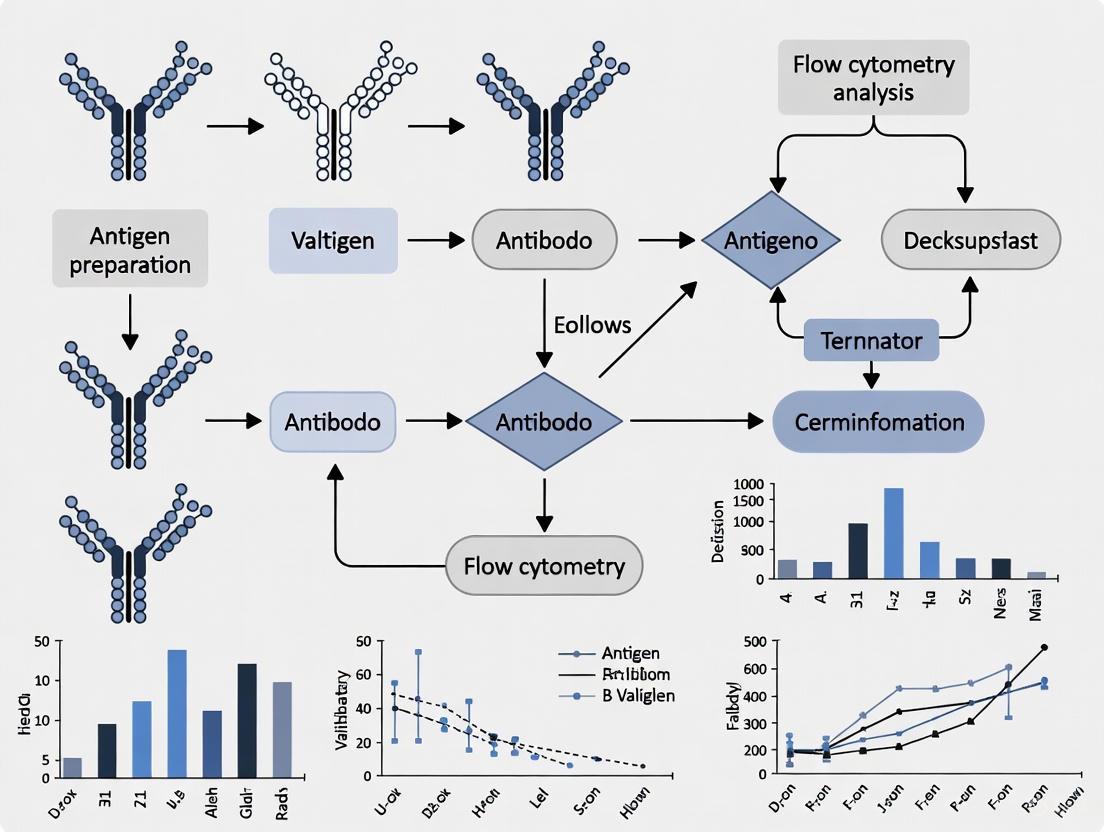

Antibody Validation Workflow Diagram

The diagram below outlines the logical decision process for validating an antibody for flow cytometry.

Antibody Validation Methods Comparison

The table below summarizes the primary experimental methods used to validate each pillar, helping you choose the right approach.

| Validation Pillar | Key Experimental Methods | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Genetic (KO/KD) [9]; Orthogonal (MS) [9]; Independent Antibodies [9] | Genetic KO provides the most compelling evidence of specificity [10]. | KO cell lines are not always available for every target [9]. |

| Selectivity | Cell Panel Profiling; Peptide Blocking [11] | Confirms the antibody works in the context of a complex biological sample. | Requires access to well-characterized cell lines or tissues. |

| Sensitivity | Antibody Titration; Use of Low-Expressing Cells | Titration is simple and essential for optimizing any assay. | Does not, by itself, prove specificity. |

| Reproducibility | Standardized Protocols [13]; Lot-to-Lot Testing; Use of Recombinant Antibodies [10] | Recombinant antibodies provide a genetic solution to batch variability. | Requires careful documentation and long-term tracking. |

A Technical Support Center Article

Why might an antibody that works perfectly in Western Blot (WB) or Immunohistochemistry (IHC) fail in my flow cytometry experiment?

It is a common and frustrating scenario in the lab: an antibody that produces clean, specific bands in WB or beautiful staining in IHC generates high background, weak signal, or nonspecific binding in flow cytometry. This failure is rarely due to the antibody itself being "bad," but rather stems from fundamental differences in how the target antigen is presented and detected across these techniques.

The core of the issue lies in epitope accessibility, sample preparation, and the live-cell context of flow cytometry. The table below summarizes the key technical reasons for these application-specific failures.

Table 1: Key Reasons for Antibody Failure Across Applications

| Technical Aspect | Western Blot (WB) | Immunohistochemistry/IHC | Flow Cytometry | Reason for Failure in Flow |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen State | Denatured, linearized [16] | Fixed, may be partially denatured [17] | Native, folded 3D structure on live/cell surface [18] [19] | Antibody may recognize only denatured sequences, not the native protein [16]. |

| Epitope Recognized | Linear epitope [17] | A mix of linear and conformational epitopes | Primarily conformational (surface) epitopes [18] | Epitope may be hidden in the native protein's 3D structure or binding may require a specific protein conformation that is absent [18]. |

| Cellular Context | Lysed cells, no spatial context | Fixed tissue, architectural context | Live/intact cells, surface integrity critical [7] | Fixation for IHC may expose internal epitopes that are inaccessible on a live cell [17]. |

| Critical Controls | Positive/Negative tissue lysates [16] | No primary antibody control [16] | Isotype, FMO, viability dyes, Fc receptor blocking [16] [4] [7] | Lack of proper controls leads to misinterpretation of non-specific binding or autofluorescence [7]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Controls for Flow Cytometry

Successful flow cytometry experiments rely on a suite of specific reagents and controls designed to address the unique challenges of staining live cells. The following table details these essential tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Flow Cytometry

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Isotype Controls [16] [7] | Matched antibody with no target specificity; assesses nonspecific Fc-mediated binding. | Must be same species, isotype, conjugation, and fluorochrome-to-protein ratio as primary antibody [7]. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent [7] | Blocks nonspecific binding of antibodies to Fc receptors on immune cells. | Critical for staining immune cells (e.g., PBMCs); reduces high background staining [7]. |

| Viability Dye [7] | Distinguishes live from dead cells. Dead cells bind antibodies nonspecifically. | Essential for assays involving tissue dissociation or stressed cells (e.g., PI, 7-AAD, DAPI) [7]. |

| Fluorescence-Minus-One (FMO) Controls [7] | Cells stained with all antibodies in a panel except one; helps set positive gates in multicolor experiments. | The gold standard for accurate gating, especially for dim markers and complex panels [7]. |

| Cell Lines: Knockout (KO) / Knockdown [18] [4] | Genetically engineered cells lacking the target protein; the gold standard for proving antibody specificity. | Provides the most direct evidence that an antibody signal is specific to the intended target [18]. |

| Compensation Beads [7] | Antibody-capture beads used to create single-color controls for instrument compensation. | More consistent than using cells for compensation controls; required for multicolor panels [7]. |

| Permeabilization Buffers [7] | Detergents (e.g., Saponin, Triton X-100) that dissolve cell membranes for intracellular staining. | Buffer strength must match target location (mild for cytoplasmic, vigorous for nuclear) [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Framework for Validating an Antibody for Flow Cytometry

Before trusting a new antibody in a critical flow experiment, follow this validation workflow to ensure specificity and optimal performance.

Goal: To confirm that an antibody specifically detects its target in your flow cytometry assay. Principle: Combine genetic strategies (KO cells) with immunological controls to unequivocally demonstrate specificity [18] [4].

FAQ: Troubleshooting Common Flow Cytometry Issues

Q1: I see a great signal, but my knockout control is also positive. What does this mean? This is a clear indicator of non-specific antibody binding. The antibody is binding to off-target proteins. Solutions include:

- Verify Specificity: Use the five-pillars framework, ensuring genetic (KO) validation supports the antibody's use [18].

- Titrate Further: The antibody concentration may be too high. Perform a detailed dilution series to find a concentration that minimizes off-target binding [7].

- Block Thoroughly: Increase the concentration or incubation time of Fc receptor blocking reagents [7].

- Check Viability: Ensure you are gating on viable cells, as dead cells are a major source of nonspecific binding [7].

Q2: My antibody works for intracellular staining after methanol permeabilization, but not for cell surface staining. Why? This is a classic sign of an antibody that recognizes a denatured, linear epitope. Methanol is a harsh solvent that denatures proteins, potentially exposing the linear sequence the antibody was raised against. For surface staining, the target protein is in its native, folded conformation, which may hide the specific linear epitope [7] [17]. You will need an antibody validated for detecting the native protein on the cell surface.

Q3: My signal is weak, even though my protein is expressed. What can I optimize? Weak signal can stem from multiple sources:

- Suboptimal Titer: The antibody may be too dilute. Titrate to find the optimal concentration [7].

- Low Antigen Abundance: Pair low-abundance targets with the brightest fluorochromes in your panel [7].

- Fixation/Permeabilization: Over-fixation (e.g., using 4% formaldehyde) can diminish signal; try a lower concentration (0.5-1%) [7]. Ensure cells are kept in permeabilization buffer during intracellular staining to prevent membrane re-sealing [7].

- Instrument Issues: Check that lasers are aligned and the correct filter sets are used for your fluorochrome [7].

Key Takeaways for Robust Flow Cytometry Data

- Application-Specific Validation is Non-Negotiable: Validation in WB or IHC does not guarantee performance in flow cytometry. Always consult validation data provided by the manufacturer specific to flow cytometry [20] [4].

- Embrace Redundant Validation: The most reliable data comes from using multiple strategies, such as combining KO cell lines with orthogonal methods like western blot to confirm target size [18] [4].

- Controls are Your Best Friend: Isotype, FMO, viability, and KO controls are not optional—they are essential for accurate data interpretation and troubleshooting [16] [7].

In flow cytometry research, the reliability of your data is fundamentally dependent on the quality and specificity of your antibodies. Antibody validation is the process of confirming that an antibody binds to its target antigen specifically and consistently within your specific experimental context, such as flow cytometry [21]. Without rigorous validation, even the most advanced cytometer will generate misleading results, jeopardizing research reproducibility and drug development outcomes. This guide examines the established validation frameworks from industry leaders and provides practical troubleshooting support to help you implement these standards in your laboratory.

Core Validation Frameworks and Standards

Leading manufacturers and service providers adhere to comprehensive, multi-faceted validation frameworks. These are designed to meet global standards such as ISO 15189 and follow guidelines from bodies like the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) and the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) [22].

The Five Pillars of Antibody Validation

A widely accepted framework, often referred to as the "five pillars," provides a robust approach to ensure antibody specificity and reliability [21].

Diagram: The Five Pillars of Antibody Validation

- Pillar 1: Genetic Strategies (Knockout/Knockdown): This method involves using cell lines or models where the gene encoding the target protein has been inactivated (knockout) or its expression significantly reduced (knockdown). The absence of a signal in these models confirms the antibody's specificity. Any remaining signal indicates potential off-target binding [21].

- Pillar 2: Orthogonal Strategies (Comparable Antibodies): This pillar involves using two or more independent antibodies that recognize different, non-overlapping regions (epitopes) of the same target protein. If these different antibodies produce congruent staining patterns and data, confidence in the results is greatly increased [21].

- Pillar 3: Independent Method Strategies (IP/MS): Immunoprecipitation (IP) is performed with the antibody in question, and the pulled-down proteins are identified using Mass Spectrometry (MS). This not only confirms the binding to the intended target but can also reveal any non-specific or off-target interactions [21].

- Pillar 4: Capture and Detection Strategies (Biological and Orthogonal Validation)

- Biological Validation: Confidence is built by confirming that the antibody staining matches the known biological characteristics of the target, such as its subcellular localization or changes in expression under specific treatments.

- Orthogonal Validation: The flow cytometry data is verified using a non-antibody-based method to measure the same target, providing strong, independent support for the results [21].

- Pillar 5: Standard and Reference Strategies (Recombinant Protein Expression): The target protein is produced recombinantly in a system that does not normally express it. This provides a pure positive control to test the antibody's specificity, typically via Western blot, where a single band at the expected molecular weight is a good indicator [21].

Key Validation Parameters for Flow Cytometry Assays

When developing and validating a flow cytometry assay itself, several analytical performance parameters must be established to ensure the assay is fit for purpose [22].

Table: Key Assay Validation Parameters and Descriptions

| Parameter | Description | Common Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Precision | Measures intra-assay (repeatability) and inter-assay (reproducibility) variability. | Coefficient of Variation (% CV) < 20% is a typical benchmark [22]. |

| Analytical Sensitivity | Defines the lowest detectable amount of the analyte. Determined via Limit of Blank (LoB) and Limit of Detection (LoD) [22]. | Based on statistical analysis of background and low-level signals. |

| Analytical Specificity | Confirms the signal is specific to the target antigen and is not affected by interference or cross-reactivity [22]. | Defined by gating strategy and reagent cross-reactivity testing. |

| Linearity & Reportable Range | The range of analyte concentrations over which the assay provides precise and accurate results [22]. | Established from the Lower Limit of Quantitation (LLOQ) to the upper limit of the assay. |

Flow Cytometry Troubleshooting FAQs

Weak or No Fluorescence Signal

- Problem: The expected fluorescence signal is faint or absent.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Inadequate Induction: If studying an inducible target, optimize treatment conditions to ensure sufficient protein expression [23].

- Fixation/Permeabilization Issues: For intracellular targets, ensure the correct fixation and permeabilization protocol is used. Cross-linking fixatives like formaldehyde must be used at an appropriate concentration (e.g., 4%) and added immediately after treatment. For methanol permeabilization, chill cells on ice first [23].

- Dim Fluorochrome Pairing: Pair low-density targets with bright fluorochromes (e.g., PE) and high-density targets with dimmer fluorochromes (e.g., FITC) [23].

- Instrument Settings: Verify that the cytometer's laser and detector (PMT) settings are configured for the excitation and emission wavelengths of the fluorochromes used [23].

High Background or Non-Specific Staining

- Problem: The negative control or off-target cell populations show unexpectedly high signal.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Fc Receptor Binding: Cells like monocytes express Fc receptors that can bind antibodies non-specifically. Block cells with BSA, normal serum, or a commercial Fc receptor blocking reagent prior to staining [23].

- Antibody Titration: Too much antibody can cause high background. Titrate your antibodies to find the optimal concentration and use the recommended number of cells (e.g., 10^5 - 10^6 cells) [23].

- Dead Cells: Dead cells exhibit autofluorescence and bind antibodies non-specifically. Use a viability dye (e.g., PI, 7-AAD, or a fixable viability dye) to gate out dead cells during analysis [23].

- Cell Autofluorescence: Certain cell types (e.g., neutrophils) are naturally autofluorescent. Use red-shifted fluorochromes (e.g., APC) or very bright fluorochromes in the affected channels to overcome this [23].

The Antibody Works in Other Applications But Not Flow Cytometry

- Problem: An antibody validated for Western Blot or IHC fails in your flow experiment.

- Possible Cause & Solution:

- Epitope Accessibility: The antibody may have been validated for a denatured, linear epitope (as in Western Blot) but may not recognize the native, folded protein on the cell surface. Always check the manufacturer's datasheet to confirm the antibody is recommended and validated for flow cytometry [23].

Poor Resolution of Cell Cycle Phases

- Problem: When performing cell cycle analysis, the histogram does not clearly distinguish G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- High Flow Rate: Running samples at a high flow rate increases the coefficient of variation (CV), leading to poor resolution. Always use the lowest flow rate setting on your cytometer for cell cycle analysis [23].

- Insufficient Staining: Ensure the cell pellet is properly resuspended in the Propidium Iodide/RNase staining solution and incubated for an adequate time (at least 10 minutes) [23].

Diagram: Troubleshooting Flow Cytometry Signal Issues

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Controls

A robust flow cytometry assay relies on the correct use of controls and reagents. The following table details essential components for your experiments.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Flow Cytometry

| Reagent / Control | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Control | Cells known to express the target antigen at high levels. Verifies the assay can detect the target reliably [22]. | Use a well-characterized cell line. Critical for assay development and troubleshooting. |

| Negative / Unstained Control | Cells that do not express the target antigen or a sample without antibody. Sets the baseline for autofluorescence and background [22]. | Essential for setting positivity gates. |

| Fluorescence Minus One (FMO) Control | Sample stained with all antibodies except one. Critical for accurate gating in multicolor panels, especially for dim markers [22]. | More reliable than isotype controls for setting gates. |

| Isotype Control | An antibody with irrelevant specificity but the same isotype as the primary antibody. Helps assess non-specific Fc-mediated binding [22]. | Considered imperfect but can be useful in some contexts. |

| Compensation Controls | Single-stained samples or beads for each fluorochrome in the panel. Corrects for spectral overlap between channels [22]. | Must be performed for every multicolor experiment. |

| Viability Dye | Distinguishes live cells from dead cells. Dead cells cause non-specific binding and must be excluded from analysis [23]. | Use fixable dyes if performing intracellular staining. |

| Calibration & QC Beads | Microbeads with known fluorescence properties and size. Used for instrument performance tracking, calibration, and standardization [22]. | Perform daily QC checks as part of a quality management system. |

Rigorous Methodologies for Flow Cytometry Antibody Validation

In functional genomics and therapeutic development, two powerful methods for probing gene function have emerged as gold standards: CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout and siRNA-mediated knockdown. While both are indispensable tools in the researcher's arsenal, they operate through fundamentally distinct mechanisms and offer complementary insights. CRISPR/Cas9 creates permanent, DNA-level disruptions, while siRNA achieves temporary, post-transcriptional silencing. Understanding their respective strengths, limitations, and optimal applications—especially when coupled with readouts like flow cytometry—is crucial for designing robust experiments, from initial target discovery to final therapeutic validation. This guide provides a technical foundation for implementing these strategies effectively and troubleshooting common challenges.

Technology Comparison: CRISPR/Cas9 vs. RNAi at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core technical characteristics of siRNA knockdown and CRISPR/Cas9 knockout.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of siRNA Knockdown and CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout

| Feature | siRNA Knockdown | CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanism | Degrades mRNA in the cytoplasm via the RISC complex [24]. | Introduces double-strand breaks in genomic DNA, leading to frameshift mutations [24]. |

| Outcome | Reversible reduction of gene expression (knockdown) [24]. | Permanent disruption of the gene (knockout) [24]. |

| Target | mRNA, cytoplasmic lncRNA, some circRNA [24]. | Coding and non-coding DNA, nuclear and cytoplasmic lncRNA, circRNA [24]. |

| Experimental Duration | Relatively fast (days to observe knockdown). | Slower (requires time for DNA repair and protein turnover). |

| Primary Risk | High off-target effects due to partial complementarity and competition with endogenous miRNAs [24]. | Low off-target effects, safeguarded by precise DNA pairing and PAM sequence requirement [24]. |

Systematic Performance Comparison in Genetic Screens

A direct, systematic comparison of parallel shRNA (similar to siRNA) and CRISPR/Cas9 screens for essential genes in K562 cells revealed critical performance insights [25].

Table 2: Empirical Performance Metrics from a Parallel Screen in K562 Cells [25]

| Performance Metric | shRNA Screen | CRISPR/Cas9 Screen | Combined Analysis (casTLE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | > 0.90 [25] | > 0.90 [25] | 0.98 [25] |

| Sensitivity (at ~1% FPR) | >60% of essential genes recovered [25] | >60% of essential genes recovered [25] | >85% of essential genes recovered [25] |

| Number of Hits Identified (at 10% FPR) | ~3,100 genes [25] | ~4,500 genes [25] | ~4,500 genes with evidence from both [25] |

| Correlation Between Screens | Low correlation, suggesting non-redundant biological information [25]. | ||

| Biological Insights | Identified distinct essential processes (e.g., chaperonin-containing T-complex) [25]. | Identified distinct essential processes (e.g., electron transport chain) [25]. | Recovers a more complete set of essential biological terms from both screens [25]. |

Technical Guide: Experimental Design & Protocols

Designing a Loss-of-Function Screen

The workflow for a typical genetic screen, adaptable for either technology, involves careful planning at each step to ensure meaningful results.

Key Protocol Steps for a Pooled Screen:

- Library Design & Selection: Use validated, pre-designed libraries with multiple guides/hairpins per gene (e.g., 4 sgRNAs/gene for CRISPR) to control for reagent efficacy [25].

- Cell Preparation & Transduction: Lentivirally transduce the target cell population (e.g., K562) at a low MOI to ensure most cells receive a single genetic element. Use sufficient cell coverage to maintain library representation [25].

- Phenotype Induction: Culture the transduced population for a sufficient duration to allow for protein turnover and phenotype manifestation (e.g., two weeks for a growth phenotype) [25].

- Sample Harvest & Sequencing: Collect cells at the start of the experiment as a reference and at the endpoint. Extract genomic DNA (for CRISPR) or RNA (for RNAi), prepare sequencing libraries for the integrated guides or hairpins, and sequence them deeply.

- Data Analysis: Use specialized algorithms (e.g., casTLE, MAGeCK) to compare the abundance of each guide/hairpin between the start and endpoint populations. Depleted guides indicate essential genes [25].

Troubleshooting FAQs: Resolving Common Experimental Issues

Q: My genetic screen yielded a high number of putative hits, but validation rates are low. What could be the cause? A: Low validation rates often point to off-target effects. This is a known challenge with RNAi, where siRNA can deregulate non-target genes with partial sequence complementarity [24]. For CRISPR, while generally lower, off-target effects can still occur. To mitigate this:

- For RNAi: Use carefully designed, pooled siRNA reagents to minimize off-targets.

- For CRISPR: Utilize bioinformatic tools to select gRNAs with high on-target and low off-target scores.

- General Practice: Always confirm phenotypes with multiple independent reagents targeting the same gene. The combination of data from both CRISPR and RNAi screens has been shown to improve the identification of true essential genes and reduce technology-specific false positives [25].

Q: Why might I observe a phenotype with CRISPR but not with siRNA (or vice versa)? A: This is a common and informative occurrence, as the technologies can reveal different biological insights [25]. Potential reasons include:

- Gene Dosage Effect: Some genes are essential only when completely knocked out (CRISPR phenotype), while a partial knockdown (siRNA) is tolerated.

- Biological Process: Certain processes, like the electron transport chain, were strongly identified by CRISPR, while others, like the chaperonin-containing T-complex, were more salient in RNAi screens [25].

- Mechanistic Differences: RNAi requires ongoing transcription and can be less effective for low-turnover proteins. CRISPR, once edited, is permanent and does not require sustained reagent expression [25].

Q: When using flow cytometry to read out my perturbation, I am seeing high background or non-specific staining. How can I resolve this? A: High background in flow cytometry can obscure genuine results.

- Block Fc Receptors: Block cells with BSA, Fc receptor blocking reagents, or normal serum to prevent antibody non-specifically binding to Fc receptors [26].

- Titrate Antibodies: Use the recommended antibody dilution. Overuse of antibody is a common cause of high background [26].

- Include Proper Controls: Use unstained cells, fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) controls, and isotype controls to set appropriate gates and identify background signals [26] [27].

- Gate Out Dead Cells: Dead cells exhibit autofluorescence and non-specific antibody binding. Use a viability dye to exclude them from your analysis [26].

Q: My flow cytometry signal for an intracellular target is weak or absent. What are the key things to check? A: Weak intracellular signal often stems from suboptimal staining protocols.

- Fixation and Permeabilization: Ensure you are using the correct protocol. Formaldehyde fixation followed by permeabilization with saponin, Triton X-100, or ice-cold methanol is common. Inadequate permeabilization will prevent antibody access [26].

- Fixative Quality: Use methanol-free formaldehyde to prevent premature cell permeabilization and loss of intracellular proteins [26].

- Fluorochrome Choice: For low-density targets, use a bright fluorochrome (e.g., PE). Save dimmer fluorochromes (e.g., FITC) for highly expressed targets [26]. Some large fluorochromes may not penetrate the nucleus efficiently.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and their critical functions for successfully executing genetic perturbation studies.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Genetic Perturbation Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Validated gRNA/shRNA Library | A library with multiple guides/hairpins per gene is crucial for controlling for reagent heterogeneity and efficacy. Confirmed specificity is key to reducing off-target effects [25] [24]. |

| Lentiviral Packaging System | Enables efficient and stable delivery of genetic perturbation constructs into a wide range of cell types, including primary and difficult-to-transfect cells. |

| Selection Antibiotics (e.g., Puromycin) | Allows for the selection of successfully transduced cells, enriching the population for those carrying the genetic construct before the screen or experiment begins. |

| Validated Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Antibodies rigorously tested for specificity, optimal dilution, and signal-to-noise ratio in flow cytometry are non-negotiable for accurate phenotyping [28]. |

| Viability Dye (e.g., PI, 7-AAD, Fixable Dyes) | Critical for distinguishing live cells from dead cells during flow analysis, as dead cells cause high background and non-specific staining [26]. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent | Reduces non-specific antibody binding, a common source of high background signal, especially in immune cells [26]. |

CRISPR/Cas9 and siRNA are not simply interchangeable tools but are complementary gold standards. CRISPR excels in creating definitive, permanent knockouts with high specificity, making it ideal for identifying essential genes and modeling loss-of-function diseases. siRNA provides reversible knockdown, useful for studying acute protein depletion and genes where complete knockout is lethal. The most robust genetic strategies often leverage both: using CRISPR for primary discovery and siRNA for independent validation or to study dosage-sensitive effects. By understanding their mechanistic differences, optimizing associated protocols like flow cytometry, and strategically applying them to specific biological questions, researchers can maximize the impact and reliability of their findings in basic science and drug development.

Core Principles of the Independent Antibody Approach

What is the independent antibody approach and why is it used in flow cytometry?

The independent antibody approach is a validation strategy that utilizes two or more antibodies targeting non-overlapping epitopes of the same antigen to confirm specificity in flow cytometry experiments. By obtaining comparable results from antibodies that recognize independent regions of the same target protein, researchers gain increased confidence that observed staining patterns truly represent specific detection of the intended target, not artifactual binding [29].

This approach is theoretically straightforward but can be challenging in practice because results may vary depending on sample preparation, buffer systems, protein conformation within complexes, and other parameters that influence epitope accessibility [29]. When multiple antibodies against the same protein show similar staining patterns despite these potential variables, this provides robust evidence of antibody specificity for your flow cytometry application.

Implementation & Methodologies

What are the key experimental designs for implementing this approach?

Direct Comparison of Staining Patterns: The most common implementation involves running parallel experiments where samples are stained with different antibody clones targeting the same protein, then comparing the resulting fluorescence patterns. Concordant results from antibodies recognizing different epitopes strongly support specificity [6] [29].

Combination with Other Validation Methods: For rigorous validation, the independent antibody approach should be combined with other strategies. The most powerful combinations include:

- Genetic strategies: Knockout (KO) or knockdown (KD) controls, where the target protein is absent or reduced [6]

- Orthogonal correlation: Comparing flow cytometry data with mRNA expression or proteomic data from the same samples [6]

- Cell treatment: Using known inducers or suppressors of target expression [6]

Polyclonal-Monoclonal Pairing: Using a polyclonal antibody (recognizing multiple epitopes) alongside a monoclonal antibody (recognizing a single epitope) provides an effective variation of this approach. Both are expected to show similar detection patterns, though sensitivity may differ [29].

What is the recommended workflow for antibody validation in flow cytometry?

The diagram below illustrates a systematic workflow for validating antibodies for flow cytometry, incorporating the independent antibody approach alongside other critical validation strategies:

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

What should I do when independent antibodies show discordant results?

Discordant results between antibodies targeting the same protein indicate a potential specificity problem or experimental issue. Consider these troubleshooting steps:

| Potential Issue | Investigation Approach | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Epitope Accessibility | Review fixation/permeabilization methods; some epitopes are masked by certain protocols [30] [31] | Optimize sample preparation; try alternative fixation/permeabilization methods |

| Antibody Concentration | Perform titration series for each antibody [31] | Determine optimal concentration for each antibody in your specific system |

| Target Confirmation | Verify target presence via alternative methods (Western blot, mRNA expression) [6] [32] | Use positive control cells known to express the target |

| Experimental Conditions | Check buffer systems, incubation times, temperatures [29] | Standardize conditions across experiments; ensure consistency |

How can I optimize staining when using multiple antibodies?

Fluorochrome Selection: For low-abundance targets, use the brightest fluorochromes (e.g., PE), while higher-abundance targets can be detected with dimmer fluorochromes (e.g., FITC) [30]. Ensure your flow cytometer has the appropriate laser and filter configurations for your fluorochrome combinations [31].

Sample Preparation: For intracellular targets, fixation and permeabilization are critical. Formaldehyde fixation followed by permeabilization with saponin, Triton X-100, or ice-cold methanol effectively exposes intracellular epitopes [30]. Note that fixation can compromise detection of some surface epitopes, so test your specific antibody-epitope combination [30].

Controls: Always include appropriate controls:

- Unstained cells

- Isotype controls

- FMO (fluorescence-minus-one) controls for multicolor panels

- Single-stained compensation controls [31]

Research Reagent Solutions

What essential materials are needed for implementing this approach?

| Reagent Type | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Independent Antibodies | Target non-overlapping epitopes of the same antigen for specificity confirmation | Multiple clones from different hosts; check epitope information when available [6] [29] |

| Fixation/Permeabilization Reagents | Enable antibody access to intracellular targets | Formaldehyde, saponin, Triton X-100, methanol; choice affects epitope accessibility [30] [31] |

| Fluorochrome Conjugates | Enable detection of antibody binding | Bright fluorophores (PE, APC) for low-abundance targets; consider tandem dyes for multiplexing [30] [31] |

| Blocking Reagents | Reduce non-specific binding | BSA, Fc receptor blockers, normal serum; critical for reducing background [30] [31] |

| Validation Controls | Verify assay specificity | Knockout cells, siRNA-treated cells, isotype controls, FMO controls [6] [31] |

Advanced Applications & Integration

How does this approach integrate with modern antibody validation frameworks?

The independent antibody approach represents one pillar of comprehensive antibody validation, which should include multiple strategies:

HLDA Workshop Validation: The Human Cell Differentiation Molecules (HCDM) organization tests flow cytometry antibodies through HLDA workshops. For example, for CD365 (TIM-1), they examined two different antibody clones from different vendors that recognized different epitopes. Both antibodies showed similar labeling patterns when transiently overexpressed in CHO cells and on different primary blood leukocytes [6].

Correlation with Orthogonal Data: Comparing flow cytometry results with antibody-independent methods like RNA sequencing or proteomics from the same samples provides additional validation. When antibody labeling intensity across different cell types correlates with expected expression levels from orthogonal data, this increases confidence in antibody specificity [6].

The decision tree below illustrates how to integrate the independent antibody approach with other validation methods throughout your experimental workflow:

What are the limitations of the independent antibody approach?

While powerful, this approach has important limitations to consider:

- Epitope Information Availability: A significant challenge is that the precise epitopes recognized by commercial antibodies are often not disclosed, making it difficult to confirm that two antibodies truly target non-overlapping regions [6].

- Differential Epitope Accessibility: Even when antibodies target different epitopes, one epitope might be inaccessible in certain protein conformations, cellular contexts, or after specific sample processing methods [29].

- Correlation vs. Proof: Correlation between independent antibodies cannot definitively prove specificity; it provides supporting evidence that should be combined with other validation approaches [6].

For the most rigorous validation, implement the independent antibody approach as part of a comprehensive strategy that includes multiple validation pillars, appropriate controls, and careful experimental design tailored to your specific research system and objectives.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the essential controls for a flow cytometry experiment to ensure biological relevance? A comprehensive set of controls is fundamental for validating your flow cytometry data. The table below summarizes the key controls, their components, and their purpose in an experiment [33].

| Control Type | Components | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Unstained Control | Cells without any antibodies. | Detects cellular autofluorescence and serves as a baseline negative control [33]. |

| Isotype Control | Cells stained with an antibody of the same isotype but irrelevant specificity. | Detects non-specific binding of the primary antibody's Fc region, helping to identify false positives [33]. |

| Viability Control | Cells stained with a viability dye (e.g., PI, 7-AAD). | Allows gating to exclude dead cells, which exhibit high non-specific staining and autofluorescence [34] [35]. |

| Positive Control | Cell lines or samples known to express the target antigen. | Confirms the antibody is working and helps identify false negatives [33] [35]. |

| Secondary Antibody Control | Cells stained only with the secondary antibody (when used). | Identifies non-specific binding from the secondary antibody [34] [33]. |

| Compensation Control | Single-stained samples for each fluorochrome used. | Corrects for fluorescent spillover (spectral overlap) into other detectors [33]. |

| FMO Control | Samples containing all fluorochromes except one. | Accurately defines gates and separates positive from negative populations, especially in complex multi-color panels [33]. |

Q2: I am not detecting a signal (or the signal is weak) for my target. What should I investigate? Weak or absent signals can stem from various issues related to your reagents, cells, or instrument. The troubleshooting table below outlines common causes and solutions [34] [35].

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Low antigen expression | Use a positive control cell line to confirm expression. Pair low-density targets with bright fluorochromes like PE or APC [34] [35]. |

| Suboptimal antibody concentration | Titrate the antibody to find the optimal concentration for your specific experiment [34]. |

| Inadequate fixation/permeabilization | For intracellular targets, optimize the fixation and permeabilization protocol. Use ice-cold methanol added drop-wise while vortexing [34] [35]. |

| Antibody degradation or storage issues | Store antibodies as recommended, protect from light, and ensure they are not expired [34]. |

| Secreted or internalized antigen | For secreted proteins, use a Golgi blocker (e.g., Brefeldin A). For surface antigens that internalize, perform staining steps at 4°C [34]. |

| Incompatible laser/PMT settings | Ensure the flow cytometer's laser wavelength and PMT voltage settings are compatible with the fluorochromes being used [34] [35]. |

Q3: My flow cytometry data shows high background or non-specific staining. How can I reduce it? High background can obscure your true signal and is often manageable by improving your staining protocol.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Presence of dead cells | Always include a viability dye to gate out dead cells during analysis [34] [35]. |

| Fc receptor binding | Block Fc receptors on cells prior to antibody incubation using BSA, FBS, or specific Fc blocking reagents [34] [33] [35]. |

| Unwashed antibodies | Include adequate wash steps after every antibody incubation to remove unbound antibody [34]. |

| High cellular autofluorescence | Use an unstained control to measure autofluorescence. For cells with high autofluorescence (e.g., neutrophils), use fluorochromes that emit in the red channel (e.g., APC) [34] [35]. |

| Excessive antibody | Titrate antibodies to use the minimum required concentration. Avoid over-staining [35]. |

Q4: How can I ensure my flow cytometry assay is reproducible over time and across laboratories? Reproducibility is critical, especially in clinical trials. It is achieved through standardization [36].

- Instrument Standardization: Perform daily quality control using reference beads to ensure consistent instrument performance and align Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) values over time [37].

- Detailed SOPs: Use a detailed Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) that covers every step from sample preparation to data analysis [36].

- Operator Training: Train at least three operators to ensure consistent performance over the life of a study [36].

- Control for Biological Variation: Process a cohort of samples from healthy donors alongside patient samples to establish a normal reference range and account for biological variability [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Optimizing Detection of Phospho-Protein Signaling

Analyzing cell signaling pathways, like the PI3K-Akt-S6 pathway, requires careful experimental design to capture dynamic phosphorylation events. The following protocol, adapted from a study on Activated PI3Kδ Syndrome (APDS), provides a robust framework [37].

Experimental Protocol: Analysis of PI3K-Akt-S6 Pathway by Flow Cytometry

1. Sample Preparation:

- Isolate fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) via Ficoll density gradient centrifugation.

- Resuspend 5 x 10^5 PBMCs in complete medium. Using fresh cells is preferred, but if freezing is necessary, freeze in 90% FCS/10% DMSO and store in liquid nitrogen [37].

2. Cell Stimulation and Staining:

- Resting Condition: Leave one set of PBMCs unstimulated to measure basal phosphorylation.

- Stimulated Condition: Stimulate another set with 15 µg/ml F(ab')2 anti-human IgM for 10 minutes at 37°C to activate the B-cell receptor pathway. This is highly recommended for samples processed more than 24 hours post-blood draw [37].

- Surface Staining: Incubate cells with surface antibodies (e.g., anti-CD19, anti-CD27) for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Fixation and Permeabilization: Fix cells immediately with pre-warmed Lyse/Fix Buffer at 37°C. Then, permeabilize cells using Perm Buffer III.

- Intracellular Staining: Stain with antibodies against phosphorylated proteins (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488 anti-pAkt (Ser473), anti-pS6) and additional intracellular markers (e.g., anti-IgD) for 30 minutes.

3. Data Acquisition and Standardization:

- Cytometer Setup: Use standardized instrument settings. Define target MFI values daily using calibration beads (e.g., Flow-Set Pro) and adjust PMT gains to maintain consistency. A bridging study can align settings between different cytometers [37].

- Gating Strategy: Identify the cell population of interest (e.g., B cells: CD19+, CD3-). Analyze the phosphorylation levels (MFI) within this gated population for both resting and stimulated conditions.

The workflow for this experimental protocol and the associated signaling pathway can be visualized as follows:

Guide 2: Addressing Issues with Receptor Occupancy Assays

Receptor Occupancy (RO) assays are crucial for developing immuno-modulatory therapies. The table below outlines key challenges and validation steps for these specialized assays [36].

| Challenge | Consideration & Solution |

|---|---|

| Low Receptor Abundance | Use an assay format with direct assessment of the bound drug to enhance sensitivity [36]. |

| Specimen Stability | Test RO on fresh whole blood, as receptors may downregulate over time. Use labs close to sample collection sites [36]. |

| Assay Format Selection | Choose from: 1. Free Receptor: Measures unbound receptors. 2. Total Receptor: Measures both free and bound receptors. 3. Bound Drug: Directly measures drug-bound receptors (best for low expression) [36]. |

| Assay Validation & Transfer | For multi-site trials: - Use the same instrument model and configuration. - Use reagents from the same lots. - Conduct a bridging study if lots or instruments differ. - Test at least three drug concentrations to validate reproducibility [36]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for setting up and troubleshooting flow cytometry experiments, particularly those involving signaling pathways [34] [37] [35].

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Fc Receptor Blockers | Reduces non-specific antibody binding by blocking Fc receptors on immune cells, lowering background staining [34] [35]. |

| Viability Dyes (PI, 7-AAD) | Distinguishes live from dead cells during analysis. Critical for excluding dead cells that cause high background [34] [35]. |

| Bright Fluorochromes (PE, APC) | Used for detecting low-density antigens to amplify the signal above background noise [34] [35]. |

| Lyse/Fix Buffer & Permeabilization Buffers | Enables intracellular staining by fixing cells to preserve internal proteins and permeabilizing membranes to allow antibody entry [37] [35]. |

| Phospho-specific Antibodies (e.g., pAkt, pS6) | Directly detect the phosphorylation status of key signaling proteins, allowing functional assessment of pathway activity [37]. |

| Stimulating Agents (e.g., F(ab')2 anti-IgM) | Activates specific cell signaling pathways (e.g., BCR) in vitro, allowing measurement of signaling capacity above basal levels [37]. |

| Calibration Beads (e.g., Flow-Set Pro) | Standardizes flow cytometer performance by setting target MFI values, ensuring day-to-day and instrument-to-instrument reproducibility [37]. |

| Isotype Control Antibodies | Matched to primary antibodies in class and conjugation; essential for distinguishing specific signal from non-specific background binding [34] [33]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is it essential to use a multimodal approach for validating antibody specificity in inflammasome research? A robust, multimodal approach is crucial because each technique has inherent limitations. Relying on a single method can lead to false conclusions. For instance, an antibody might produce a signal in flow cytometry that appears specific, but when the same antibody is used for immunofluorescence (IF), it could show inappropriate subcellular localization, revealing a lack of true specificity [38]. Cross-validation with Western blot (WB) can further confirm the presence and size of the target protein, ensuring the antibody recognizes the correct antigen across different experimental conditions [39] [38].

Q2: In a flow cytometry assay for ASC speck formation, what is an acceptable positive signal, and how is it quantified? In a well-optimized assay using THP-1 monocytes with canonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation (LPS priming followed by nigericin), a significant increase in ASC speck-positive cells is observed. For example, positive cells might increase from a baseline of 4.86% to 15.03% after stimulation, a change that should be statistically significant (e.g., p < 0.01) [39]. Quantification is typically done by flow cytometry based on changes in fluorescence pulse geometry or by manually counting cells with punctate fluorescent specks in immunofluorescence microscopy [39].

Q3: My flow cytometry data shows high background staining. What are the primary causes and solutions? High background is a common issue often stemming from non-specific antibody binding or the presence of dead cells. Key causes and solutions include [40]:

- Fc Receptor Binding: Cells like monocytes express Fc receptors that can bind antibodies non-specifically. Solution: Block cells with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Fc receptor blocking reagents, or normal serum from the host species of your primary antibody.

- Dead Cells: Dead cells frequently exhibit non-specific staining. Solution: Use a viability dye to gate out dead cells during analysis.

- Excessive Antibody: Using too much antibody can saturate the specific signal. Solution: Titrate your antibodies to determine the optimal concentration.

- Cell Autofluorescence: Certain cell types, like neutrophils, naturally autofluoresce. Solution: Use fluorochromes that emit in red-shifted channels (e.g., APC instead of FITC), which are less prone to autofluorescence [40].

Q4: How can I confirm that my antibody is suitable for flow cytometry, especially for intracellular targets like ASC? Antibody validation for flow cytometry requires a multi-pronged approach [6] [38]:

- Use Biologically Relevant Controls: Include untreated/unstimulated controls, isotype controls, and, critically, cells where the target protein is known to be absent (e.g., knockout cell lines) or present at different levels.

- Correlate with Orthogonal Data: Compare your flow data with mRNA expression data (e.g., from RNAseq) or proteomic data from multiple cell lines with varying expression levels of your target.

- Leverage Cell Treatment: Use known pathway activators or inhibitors. For ASC specks, this involves comparing unstimulated cells to those treated with LPS/nigericin [39]. A valid antibody should show a corresponding change in signal.

- Check Independent Validation: Look for antibodies that are approved by workshops like the Human Cell Differentiation Molecules (HCDM), which rigorously test antibodies for specific targets [6].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Weak or No Fluorescence Signal in Flow Cytometry

| Possible Cause | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Inadequate Fixation/Permeabilization | For intracellular targets like ASC, optimize fixation and permeabilization. Use formaldehyde for fixation, followed by permeabilization with agents like saponin, Triton X-100, or ice-cold methanol. Ensure methanol is added drop-wise to ice-cold cells to prevent hypotonic shock [40]. |

| Dim Fluorochrome for Low-Abundance Target | Pair the brightest fluorochrome (e.g., PE) with the lowest density target. Use dimmer fluorochromes (e.g., FITC) for highly abundant targets [40]. |

| Suboptimal Instrument Settings | Verify that the laser and photomultiplier tube (PMT) settings on the flow cytometer are compatible with the excitation and emission wavelengths of the fluorochromes being used [40]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Flow Cytometry, Western Blot, and Immunofluorescence

| Possible Cause | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Differential Epitope Accessibility | The target protein's epitope (the region an antibody binds to) may be exposed in one technique (e.g., denatured WB) but hidden or altered in another (e.g., in its native conformation in flow or IF). Validate antibodies across all intended applications [38]. |

| Incomplete Protein Extraction for WB | ASC specks form large, insoluble aggregates. Standard lysis buffers may not solubilize them. For WB analysis of ASC oligomers, the insoluble fraction of the cell lysate must be cross-linked with DSS before analysis [39]. |

| Antibody Specificity Issues | An antibody may work in one application but not another. Employ multiple validation strategies, such as knockout/knockdown controls, peptide blocking, and comparison to orthogonal data, to confirm antibody specificity for your specific use case [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Multimodal Detection

Integrated Workflow for Detecting ASC Speck Formation

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for the multimodal detection of ASC speck formation, as applied in recent research [39]:

Detailed Methodologies

Cell Culture and Canonical NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation [39]

- Culture: Maintain THP-1 human monocytic cells in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol at 37°C and 5% CO₂.

- Priming: Seed cells at an appropriate density and prime with 100 nM Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 16 hours to induce differentiation into macrophage-like cells. Replace the medium with RPMI containing 2% FBS.

- Activation: Stimulate the cells with 50 ng/mL Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 4 hours. Subsequently, treat with 7.5 μM Nigericin for 1 hour to induce inflammasome assembly.

Flow Cytometry for ASC Speck Detection [39]

- Cell Harvest: After stimulation, detach cells using an enzyme-free dissociation reagent like TrypLE Express.

- Fixation and Permeabilization: Fix cells with 0.25% formaldehyde for 10 minutes on ice. Permeabilize in cold 90% ethanol for 15 minutes.

- Staining: Incubate cells with an Fc-block, then with anti-ASC primary antibody (e.g., 1:750 dilution), followed by an FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., 1:1500 dilution). Use a blocking buffer (0.1% BSA, 2% FBS in PBS) for antibody dilution.

- Analysis: Analyze cells on a flow cytometer. ASC specks are identified based on a high fluorescence intensity area and a change in pulse geometry, indicating a bright, punctate signal compared to diffuse cytoplasmic staining.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy [39]

- Seeding: Seed THP-1 cells on sterile glass coverslips in a 24-well plate and follow the stimulation protocol.

- Fixation and Permeabilization: Wash cells with PBS and fix with 4% formaldehyde. Permeabilize with a solution of 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1% BSA in PBS.

- Staining: Incubate with anti-ASC primary antibody, followed by a fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibody. Include DAPI to stain nuclei.

- Imaging and Quantification: Visualize specks using a fluorescent cell imager. Manually count cells with punctate ASC foci across random fields. Calculate the percentage of ASC speck-positive cells by dividing the number of speck-positive cells by the total number of DAPI-stained nuclei.

Western Blot for ASC Oligomer Detection [39]

- Lysis and Fractionation: After stimulation, rinse cells with ice-cold PBS. Lyse cells using NP-40 lysis buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Centrifuge to separate soluble and insoluble fractions.

- Cross-Linking: Wash the insoluble pellet (containing the ASC speck) with PBS. Resuspend and cross-link the proteins in the pellet using 1 mM disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Analysis: Pellet the cross-linked oligomers, resuspend in Laemmli buffer, boil, and analyze by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, probing for ASC.

Antibody Validation Framework

The following pathway outlines a systematic, multi-technique approach to validate antibodies for flow cytometry and ensure reliable cross-platform results:

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their functions in multimodal inflammasome activation and detection assays, as derived from the cited protocols [39].

| Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| THP-1 Human Monocytes | A widely used human monocytic cell line that can be differentiated into macrophage-like cells, serving as a standard model for studying NLRP3 inflammasome activation. |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | A pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) used as the "priming" signal. It upregulates the expression of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β, preparing the cell for inflammasome assembly. |

| Nigericin | A potassium ionophore derived from Streptomyces hygroscopicus. It acts as the "activation" signal for the NLRP3 inflammasome, triggering the assembly of the inflammasome complex. |

| Anti-ASC Antibody | The primary antibody used to detect the adaptor protein ASC. Its aggregation into a single speck is the hallmark readout for inflammasome activation in flow cytometry, IF, and WB. |

| Disuccinimidyl Suberate (DSS) | A cross-linker used in Western blot protocols to covalently stabilize the large, insoluble ASC oligomers formed during speck formation, allowing for their detection via SDS-PAGE. |

| Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitors | Added to lysis buffers to prevent the degradation and dephosphorylation of proteins during sample preparation, preserving the native state of proteins for accurate analysis. |