Overcoming Computational Bottlenecks in Large-Scale NGS Immunology Data Analysis

The exponential growth of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) data in immunology presents significant computational challenges that can hinder research progress and clinical translation.

Overcoming Computational Bottlenecks in Large-Scale NGS Immunology Data Analysis

Abstract

The exponential growth of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) data in immunology presents significant computational challenges that can hinder research progress and clinical translation. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to navigate these bottlenecks. We explore the foundational sources of computational complexity in immunogenomics, detail cutting-edge methodological approaches from machine learning to specialized pipelines, offer practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for data processing and storage, and establish rigorous validation and comparative analysis frameworks. By synthesizing solutions across these four core areas, this guide aims to empower the immunology community to efficiently leverage large-scale NGS data for breakthroughs in basic research, therapeutic discovery, and clinical applications.

Understanding the Computational Challenges in NGS Immunology

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common initial bottlenecks in an NGS immunology workflow? The most common initial bottlenecks are often related to data quality and computational infrastructure. Sequencing errors, adapter contamination, and low-quality reads can compromise data integrity from the start [1]. Furthermore, the raw FASTQ files generated by sequencers are large and require significant storage and processing power, which can overwhelm limited computational resources [2].

2. My single-cell Rep-Seq data shows paired-chain information. Why is this a challenge? Paired-chain information adds a layer of complexity because each cell can contain multiple receptor sequences (productive and non-productive). This makes quantifying cells and grouping them into clonotypes more challenging than with bulk sequencing, which typically uses only a single chain for analysis. Most standard analysis tools are not designed to handle this paired information, which can lead to a loss of valuable data [3].

3. How can I integrate sparse single-cell data with deep bulk sequencing data? This is a key challenge as the datasets are complementary but different in scale. Single-cell datasets may characterize thousands of cells, while bulk sequencing can cover millions. Specialized computational tools are required to synergize these data sources, as they contain complementary information. The integration allows high-resolution single-cell data to enrich the deeper, but less resolved, bulk data [3].

4. What is the purpose of the BAM and CRAM file formats? BAM (Binary Alignment/Map) and CRAM are formats for storing sequence alignment information. BAM is the compressed, binary version of the human-readable SAM format, allowing for rapid processing and reduced storage space. CRAM offers even greater compression by storing only the differences between the aligned sequences and a reference genome, but it requires continuous access to the reference sequence file [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Quality Control Metrics in Raw Sequencing Data

Problem: A FastQC report indicates poor per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, or high levels of duplicate reads.

Solution:

- Interpret the FastQC Report: Use FastQC to generate a quality report for your raw FASTQ files. Pay close attention to the "Per Base Sequence Quality" and "Adapter Content" modules [5].

- Perform Trimming and Adapter Removal: Use tools like Cutadapt to remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences. A typical command includes:

-m 10: Discards reads shorter than 10 bases after trimming.-q 20: Trims bases with a quality score below 20 from the 3' end.-j 4: Uses 4 processor cores [5].

- Re-run Quality Control: Always run FastQC on the trimmed FASTQ files to confirm quality improvement [5].

- Aggregate Reports: Use MultiQC to compile a single report from multiple FastQC outputs, making it easier to compare samples [5].

Issue 2: Computational Limitations Slowing Down Data Processing

Problem: Alignment or variant calling is taking too long or failing due to memory errors.

Solution:

- Understand Your Computational Problem: Determine if your analysis is "disk-bound," "memory-bound," or "computationally-bound" [2]. This will guide your solution.

- Optimize File Formats: Process data in compressed BAM or CRAM formats instead of uncompressed SAM to reduce I/O load [4].

- Leverage Cloud or Heterogeneous Computing: For large-scale data, consider cloud computing platforms that can provide on-demand resources, or investigate specialized hardware accelerators for specific computationally intense tasks [2].

- Use Standardized, Optimized Pipelines: Implement standardized workflows to ensure consistency and efficiency. These are often optimized for performance and resource usage [1].

Issue 3: Challenges in Analyzing Adaptive Immune Receptor Repertoire Sequencing (AIRR-seq) Data

Problem: Difficulty in accurately annotating V(D)J segments, determining clonality, or comparing repertoires across individuals.

Solution:

- Ensure Accurate Germline Gene Annotation: Use specialized VDJ annotation tools (e.g., IgDiscover, TiGER) with the most appropriate germline reference database. For precise work, consider inferring individual-specific germline genes from the data itself [6].

- Apply Advanced Clustering and Network Analysis: Use computational methods that leverage network theory to group similar immune receptor sequences into clonotypes, visualizing relationships and clonal expansion [6].

- Measure Diversity Appropriately: Employ a range of diversity metrics (e.g., clonotype diversity profiles) to quantitatively compare the complexity of immune repertoires between different conditions or time points [6].

- Investigate Sequence Convergence: Use statistical and machine learning methods to identify sequences that are shared across individuals (convergent) which may indicate a common immune response [6].

Essential File Formats in NGS Immunology

The table below summarizes the key file formats you will encounter in your NGS immunology analysis workflow.

| File Format | Primary Function | Key Characteristics | Example Tools/Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| FASTA [4] | Stores reference nucleotide or amino acid sequences. | Simple text format starting with a ">" header line, followed by sequence data. | Reference genomes, germline gene sequences. |

| FASTQ [4] [7] | Stores raw sequencing reads and their quality scores. | Each read takes 4 lines: identifier, sequence, a separator, and quality scores (ASCII encoded). | Primary output from sequencers; input for QC tools like FastQC. |

| SAM/BAM [4] [7] | Stores aligned sequencing reads. | SAM is human-readable text; BAM is its compressed binary equivalent. Contains header and alignment sections. | Output from aligners like BWA or STAR; input for variant callers. |

| CRAM [4] | Stores aligned sequencing reads. | Highly compressed format that references an external genome sequence file. | Efficient storage and data transfer. |

| BED/GTF [4] | Stores genomic annotations (e.g., genes, exons). | Tab-delimited text files defining the coordinates of genomic features. | Defining target regions for variant calling. |

| bedGraph [4] | Stores continuous-valued data across the genome. | A variant of BED format that associates a genomic region with a numerical value. | Visualizing coverage or gene expression data. |

Experimental Protocol: Standard Pre-processing for NGS Immunology Data

This protocol provides a foundational workflow for quality control and pre-processing of raw NGS data, which is critical for all downstream immunological analyses [8] [5].

1. Objectives

- To assess the quality of raw sequencing data from an immunology experiment (e.g., AIRR-seq, RNA-seq).

- To remove technical artifacts such as adapter sequences and low-quality bases.

- To generate cleaned sequence data ready for alignment and subsequent analysis.

2. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Raw FASTQ files | The starting input data containing raw sequence reads and quality scores from the sequencer. |

| FastQC [5] | A quality control tool that generates a comprehensive HTML report with multiple modules to visualize data quality. |

| Cutadapt [5] | A tool to find and remove adapter sequences, primers, and other types of unwanted sequence data through quality trimming. |

| MultiQC [5] | A tool that aggregates results from multiple bioinformatics analyses (e.g., several FastQC reports) into a single summarized report. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) or Cloud Environment [2] | Computational resources with sufficient memory and processing power to handle large NGS datasets. |

3. Procedure

- Initial Quality Check:

- Navigate to the directory containing your raw

*.fastq.gzfiles. - Run FastQC on the raw files and specify an output directory:

- Open the generated HTML report to inspect key metrics like per-base sequence quality and adapter contamination.

- Navigate to the directory containing your raw

Trimming and Adapter Removal:

- Based on the FastQC report, use Cutadapt to perform quality and adapter trimming. A standard command is:

- This command discards reads shorter than 20 bp (

-m 20), trims low-quality bases (Q<20) from both the 5' and 3' ends (-q 20,20), and uses 8 cores (-j 8).

Post-Trimming Quality Assessment:

- Run FastQC again on the newly created trimmed FASTQ file to verify the improvement in data quality.

Report Aggregation:

- Use MultiQC to compile all FastQC reports (from both raw and trimmed data) into one easy-to-view report.

- The

-sflag ensures unique naming for all samples in the final report.

4. Data Analysis Compare the MultiQC report before and after trimming. Successful pre-processing will show:

- Improved per-base sequence quality, particularly at the ends of reads.

- Elimination or significant reduction of adapter content.

- A reduction in the number of sequence reads due to the removal of low-quality or short sequences, but a higher overall quality of the retained data.

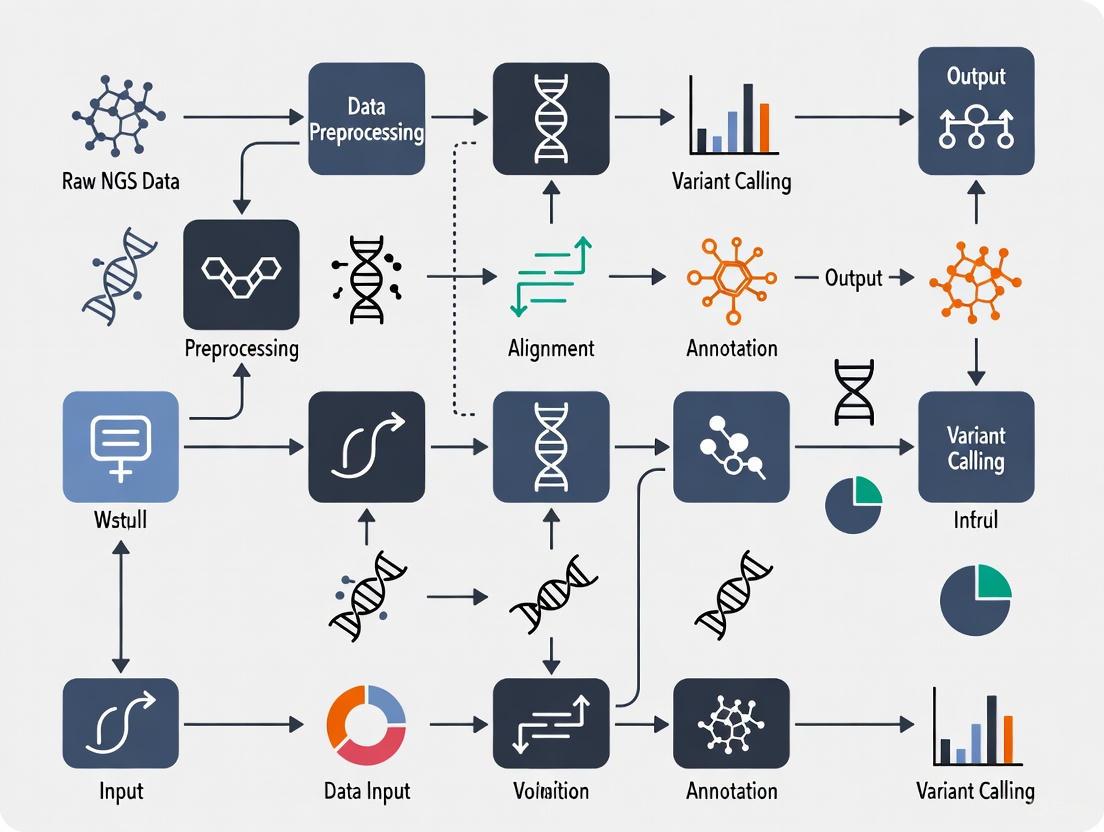

Workflow Visualization

NGS Immunology Data Analysis Flow

Single-Cell Barcoding Concept

FAQs: Troubleshooting Common NGS Bottlenecks

Data Storage and Management

Q: Our data storage costs are escalating rapidly with increasing sequencing volume. What are the key strategies for cost-effective data management? A: Effective data management requires a multi-layered approach. First, implement data lifecycle policies to archive or remove raw data after secondary analysis, as the sheer volume of multiomic data is a primary cost driver [9]. Second, leverage cloud-based systems for scalable storage and high-performance computing, which help address data bottlenecks and enable efficient data sharing [10]. For large-scale initiatives, adopting standardized data formats like those from the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH) improves interoperability and reduces storage complexity [11].

Q: How can we ensure our genomic data is FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable)? A: Adhering to the FAIR principles requires thorough documentation of all data processing steps and consistent use of version control for both data and code. Utilizing electronic lab notebooks and workflow management systems like Nextflow or Snakemake helps automatically capture these details, ensuring reproducibility and proper data stewardship [11].

Sequencing Errors and Quality Control

Q: A high proportion of our NGS reads contain ambiguities. How should we handle this data for reliable clinical interpretation? A: The optimal strategy depends on the error pattern. For random, non-systematic errors, the neglection strategy (removing sequences with ambiguities) often provides the most reliable prediction outcome [12]. However, if a large fraction of reads contains errors, potentially introducing bias, the deconvolution strategy with a majority vote is preferable, despite being computationally more expensive. Research indicates that the worst-case assumption strategy generally performs worse than both other methods and can lead to overly conservative clinical decisions [12].

Q: Our NGS runs are showing low library yields. What are the most common causes and solutions? A: Low library yield is frequently traced to issues in the pre-analytical phase. The table below outlines common causes and corrective actions [13].

| Cause | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality | Enzyme inhibition from contaminants (salts, phenol) | Re-purify input sample; ensure wash buffers are fresh; target high purity (260/230 > 1.8). |

| Inaccurate Quantification | Suboptimal enzyme stoichiometry from pipetting errors | Use fluorometric methods (Qubit) over UV; calibrate pipettes; use master mixes. |

| Fragmentation Issues | Over-/under-fragmentation reduces adapter ligation efficiency | Optimize fragmentation parameters (time, energy); verify fragmentation profile. |

| Suboptimal Ligation | Poor ligase performance or wrong adapter-to-insert ratio | Titrate adapter:insert ratios; ensure fresh ligase and buffer; maintain optimal temperature. |

Q: What is the typical failure rate for NGS in rare tumor samples, and how do different assays compare? A: A 2025 study on rare tumors found that 14.7% of NGS tests failed due to insufficient quantity or quality of material, affecting 4.7% of patients [14]. The assay type significantly impacted the failure rate. Whole Exome/Transcriptome Sequencing (WETS) was associated with a significantly higher probability of failure compared to smaller targeted panels (Odds Ratio: 11.4). The good news is that repeated testing was successful in 7 out of 8 patients, offering a path to recover from initial failure [14].

Bioinformatics Workflows

Q: Our bioinformatics pipelines are slow, not reproducible, and costly to run. When and how should we optimize them? A: Optimization should begin when usage scales justify the investment, potentially saving 30-75% in time and costs [15]. The process can be broken into three stages:

- Analysis Tools: Identify and implement improved tools, focusing first on the most demanding or unstable points in your pipeline [15].

- Workflow Orchestrator: Introduce a dynamic resource allocation system (e.g., Nextflow) to prevent over-provisioning and reduce computational costs [15].

- Execution Environment: Ensure your compute environment (especially cloud configurations) is cost-optimized to avoid unnecessary expenses [15].

Q: How can automation improve our NGS workflow? A: Integrating automation at various stages enhances consistency and reproducibility. In wet-lab steps, automated pipetting and sample handling reduce human error in DNA/RNA extraction and library preparation [10]. In computational analysis, automation enables features like automatic pipeline triggers upon data arrival, periodic runs, and version tracking, which significantly reduce manual intervention and improve reproducibility [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Data Quality Issues

The "Garbage In, Garbage Out" (GIGO) principle is critical in bioinformatics; poor input data quality inevitably leads to misleading results [11]. Follow this systematic diagnostic flow:

NGS Data Quality Diagnostic Flow

Recommended Error Handling Strategies for Ambiguous Bases: Based on a comparative study, the choice of error handling strategy directly impacts the reliability of clinical predictions [12].

| Strategy | Description | Best For | Performance Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neglection | Removes all sequences containing ambiguities (N's). | Scenarios with random, non-systematic errors. | Outperforms other strategies when no systematic errors are present. |

| Deconvolution (Majority Vote) | Resolves ambiguities into all possible sequences; the majority prediction is accepted. | Cases with a high fraction of ambiguous reads or suspected systematic errors. | Computationally expensive but avoids bias from data loss; better than worst-case. |

| Worst-Case Assumption | Always assumes the ambiguity represents the nucleotide worst for therapy (e.g., resistance). | Generally not recommended. | Performance is worse than both neglection and deconvolution strategies. |

Guide 2: Optimizing and Scaling Bioinformatics Workflows

For labs experiencing growing computational demands, migrating to modern, scalable workflow orchestrators is key. A case study with Genomics England successfully transitioned to Nextflow-based pipelines to process 300,000 whole-genome sequencing samples, demonstrating the feasibility of large-scale optimization [15].

Bioinformatics Workflow Optimization Roadmap

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorometric Assay Kits (Qubit) | Accurate quantification of usable nucleic acid concentration, specific to DNA or RNA. | Prefer over UV absorbance (NanoDrop) which can overestimate by counting contaminants [13]. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | Amplifies library fragments with minimal introduction of errors during PCR. | Essential for maintaining sequence accuracy; minimizes amplification bias [13]. |

| Magnetic Beads (SPRI) | Purifies and size-selects nucleic acid fragments after enzymatic reactions (e.g., fragmentation, ligation). | Incorrect bead-to-sample ratio is a common pitfall, leading to size selection failures or sample loss [13]. |

| Platform-Specific Adapters | Allows DNA fragments to bind to the sequencing platform and be amplified. | Adapter-to-insert molar ratio must be optimized; excess adapters promote adapter-dimer formation [13] [16]. |

| Fragmentation Enzymes | Shears DNA into uniformly-sized fragments suitable for sequencing. | Over- or under-shearing reduces ligation efficiency and compromises library complexity [13]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

▸ FAQ 1: How do data quality and error profiles differ between Illumina and Ion Torrent, and what is the impact on immunology data?

The fundamental difference in sequencing chemistry between the two platforms leads to distinct error profiles that can significantly impact the analysis of immunology data, such as T-cell receptor (TCR) or B-cell receptor (BCR) sequencing.

Answer: Illumina and Ion Torrent technologies employ different detection methods: Illumina uses optical detection of fluorescence signals, while Ion Torrent detects pH changes using semiconductor technology [17]. This fundamental difference results in distinct error profiles.

Illumina sequencing is characterized by high base-call accuracy, with the majority of bases scoring Q30 and above, representing a 99.9% base call accuracy [18]. This high fidelity is crucial for detecting rare clonotypes in immune repertoire sequencing.

In contrast, Ion Torrent sequencing is prone to homopolymer errors (insertions and deletions), though it typically offers longer read lengths and shorter run times [17]. These homopolymer errors can cause frameshifts during translation in gene-based analyses, which is particularly problematic for immunology applications that rely on accurate V(D)J segment identification.

The following table summarizes the key technical differences and their implications for immunology applications:

Table 1: Platform Comparison and Impact on Immunology Data

| Feature | Illumina | Ion Torrent | Impact on Immunology Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemistry | Optical (fluorescence) [17] | Semiconductor (pH change) [17] | - |

| Primary Error Type | Substitution errors [18] | Homopolymer indels [17] | Frameshifts disrupt CDR3 translation and clonotype assignment. |

| Typical Read Length | Shorter (e.g., 2x150 bp, 2x300 bp) [17] | Longer reads [17] | Advantageous for covering full-length antibody genes. |

| Run Time | Generally longer [17] | Shorter [17] | Faster turnaround for time-sensitive studies. |

| Ideal for Immunology | High-fidelity clonotype tracking, minimal frameshift artifacts. | Targeted panels with frameshift filtering; requires careful data handling. | - |

▸ FAQ 2: My cgMLST analysis from mixed platform data shows inconsistent clustering. What is the cause and how can I resolve it?

Inconsistent clustering in core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST) is a known challenge when integrating data from different sequencing platforms. The root cause often lies in the technology-specific error profiles.

Answer: A study on Listeria monocytogenes directly compared cgMLST results from Illumina and Ion Torrent data. It found that for the same strain, the average allele discrepancy between platforms was 14.5 alleles, which is well above the commonly used threshold of ≤7 alleles for cluster detection in outbreak investigations [17]. This incompatibility can lead to both false-positive and false-negative clusters in immunology studies, such as tracking pathogen-specific immune responses.

Primary Cause: Homopolymer errors in Ion Torrent data lead to frameshift mutations, which cause premature stop codons or altered gene lengths. This results in alleles being called as different when they are, in fact, identical [17].

Solution: Apply a frameshift filter during cgMLST analysis.

- Relative Frameshift Filter (f.s.r.): Removes alleles if their length deviates by a relative fraction (e.g., 0.1) from the median length of all alleles for that locus [17].

- Absolute Frameshift Filter (f.s.a.): Removes alleles if their length deviates by an absolute number of base pairs (e.g., 9 bp) from the median [17].

Applying a strict frameshift filter can reduce the mean allele discrepancy below the 7-allele threshold, improving cluster concordance, though it may slightly reduce discriminatory power [17].

▸ FAQ 3: What are the best practices for designing experiments that combine data from both platforms?

Successfully integrating data from Illumina and Ion Torrent requires careful planning from the experimental design stage through to bioinformatic analysis.

Answer: To ensure compatibility and data quality in mixed-platform immunology studies, follow these best practices:

- Standardize Wet-Lab Protocols: Implement standardized protocols for sample preparation, library construction, and quality control across all participating labs to minimize technical variability [19].

- Use a Common DNA Source: Where possible, use a common source of high-quality DNA for sequencing on different platforms to isolate technology-specific effects from biological variation [17].

- Select the Right Assembler: Not all assemblers handle data from both platforms equally well. The study on L. monocytogenes found that SPAdes was the only assembler that delivered qualitatively comparable results for both Illumina and Ion Torrent data [17].

- Prioritize SNP Analysis for Integration: If your immunology question allows, consider using read-based single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis. The same study found that the impact of the sequencing platform on SNP analysis was lower than its impact on cgMLST [17].

- Implement Frameshift Filtering: As noted in FAQ 2, always apply frameshift filters to cgMLST data derived from Ion Torrent or mixed-platform studies [17].

- Utilize Positive Controls: Spike in a known control (e.g., 20% PhiX for Illumina) during sequencing to act as a positive control for clustering and to monitor run quality [20].

▸ FAQ 4: How can I troubleshoot a complete sequencing failure, such as a "Cycle 1" error on my MiSeq?

A "Cycle 1" error indicates a fundamental failure in the initial phase of the sequencing run, where the instrument cannot find sufficient signal to focus.

Answer: "Cycle 1" errors on an Illumina MiSeq (with error messages like "Best focus not found" or "No usable signal found") can be due to library, reagent, or instrument issues [20]. Follow this systematic troubleshooting workflow to diagnose and resolve the problem.

Diagram 1: MiSeq Cycle 1 Error Troubleshooting Workflow

Key Investigation Steps for Library and Reagents:

- Reagent Kits: Check for expiration dates and ensure proper storage conditions [20].

- Library Quality: Verify the quality and quantity of your library using Illumina-recommended fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) – do not rely solely on absorbance (NanoDrop) [13] [20].

- Library Design: Ensure your library design, including any custom primers (common in immunology panels), is compatible with the Illumina platform [20].

- NaOH Dilution: Confirm that a fresh dilution of NaOH was used for denaturation and that its pH is above 12.5 [20].

▸ FAQ 5: My library yield is low. What are the common causes and how can I improve it?

Low library yield is a frequent bottleneck that can derail NGS projects. The causes can be traced to several steps in the preparation process.

Answer: Low final library yield can result from issues at multiple stages. The table below outlines common root causes and their corrective actions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low NGS Library Yield

| Root Cause | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality | Enzyme inhibition from contaminants (phenol, salts, EDTA) or degraded DNA/RNA [13]. | Re-purify input sample; ensure high purity (260/230 > 1.8); use fluorometric quantification (Qubit) [13]. |

| Fragmentation Issues | Over- or under-fragmentation produces fragments outside the optimal size range for adapter ligation [13]. | Optimize fragmentation parameters (time, energy); verify fragment size distribution post-shearing. |

| Suboptimal Adapter Ligation | Poor ligase performance or incorrect adapter-to-insert molar ratio reduces library molecule formation [13]. | Titrate adapter:insert ratio; use fresh ligase and buffer; ensure optimal reaction temperature. |

| Overly Aggressive Cleanup | Desired fragments are accidentally removed during bead-based purification or size selection [13]. | Precisely follow bead-to-sample ratios; avoid over-drying beads; use validated cleanup protocols. |

▸ Computational Considerations for Large-Scale NGS Immunology Data

Framing the aforementioned challenges within the context of solving computational bottlenecks requires a holistic strategy that extends from the sequencer to the analysis software.

1. Leverage AI-Powered Tools: The field is shifting towards AI-based bioinformatics tools that can increase analysis accuracy by up to 30% while cutting processing time in half [21]. Tools like DeepVariant use deep learning for more accurate variant calling, which is critical for identifying somatic hypermutations in immunoglobulins [22] [21].

2. Adopt Cloud Computing: The massive volume of data from mixed-platform studies often exceeds local computational capacity. Cloud platforms (AWS, Google Cloud Genomics) provide scalable infrastructure, enable global collaboration, and are cost-effective for smaller labs [22]. They also implement stringent security protocols compliant with HIPAA and GDPR [22].

3. Implement Standardized Pipelines: Reproducibility is a major challenge when integrating diverse datasets. Adopt community-validated workflows for preprocessing, normalization, and analysis [19]. For immune repertoire analysis, using standardized tools like MiXCR—a gold-standard tool used in 47 of the top 50 research institutions—ensures consistency and accuracy across projects and platforms [19].

Diagram 2: Computational Pipeline for Multi-Platform Immunology Data

▸ The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for NGS Immunology Workflows

| Item / Tool | Function | Relevance to Immunology & Platform Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| SPAdes Assembler | Genome assembly from sequencing reads. | Crucial for generating comparable assemblies from both Illumina and Ion Torrent data [17]. |

| Frameshift Filters (f.s.r., f.s.a.) | Bioinformatic filters for cgMLST analysis. | Mitigates homopolymer errors from Ion Torrent data, enabling integration with Illumina datasets [17]. |

| PhiX Control Library | Sequencing run quality control. | Serves as a positive control to diagnose platform-specific issues (e.g., "Cycle 1" errors) [20]. |

| Fluorometric Quantifier (e.g., Qubit) | Accurate quantification of DNA/RNA. | Prevents low yield and failed libraries by measuring only usable nucleic acids, not contaminants [13]. |

| MiXCR Software | Specialized tool for immune repertoire analysis. | Provides a standardized, high-performance pipeline for analyzing TCR and BCR sequencing data [19]. |

| Illumina DNA Prep Kit | Library preparation for Illumina platforms. | Standardized, high-quality library construction to minimize prep-related bias [17]. |

| Ion Plus Fragment Library Kit | Library preparation for Ion Torrent platforms. | Optimized library construction for semiconductor sequencing [17]. |

In large-scale NGS immunology research, the boundary between laboratory preparation and computational analysis is not just crossed frequently—it is a major site of operational friction. Errors introduced during library preparation do not merely compromise sample quality; they actively distort downstream bioinformatics processes, exacerbating computational bottlenecks and consuming precious processing time, storage, and financial resources [23] [24].

This guide addresses the critical interplay between library preparation and computational load, providing targeted troubleshooting to help researchers and drug development professionals produce cleaner data, ensure more efficient analysis, and accelerate discovery.

Troubleshooting FAQs: From Library Prep Error to Computational Symptom

FAQ 1: My sequencing run finished, but the variant caller reported extremely high duplicate reads and poor genome coverage. What went wrong in library prep?

- Problem: High duplication rates and flat coverage are classic computational symptoms of low library complexity, meaning an insufficient number of unique DNA fragments were sequenced.

- Primary Library Prep Cause: This is frequently caused by low input DNA/RNA, degraded starting material, or overly aggressive PCR amplification during library construction [13]. Poor input quality forces the sequencer to repeatedly read the same limited set of fragments.

- Computational Impact: Variant callers like GATK and FreeBayes waste significant processing power analyzing duplicate reads, which provide no new biological information and increase false positive rates [25] [26]. This leads to longer compute times and unreliable results.

- Solution:

- Verify Input Quality: Use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) over UV absorbance to ensure accurate measurement of amplifiable DNA. Check RNA Integrity Numbers (RIN) for RNA-seq.

- Limit PCR Cycles: Use the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary for library amplification. If yield is low, it is better to repeat the amplification than to add excessive cycles [27] [13].

- Assess Post-Ligation Yield: Check library yield after the ligation step, before PCR, to identify if amplification is masking an underlying inefficiency.

FAQ 2: My data analysis reveals a high percentage of reads that won't align to the reference genome. What is the likely culprit?

- Problem: A low alignment rate in tools like BWA or HISAT2 indicates a large proportion of sequences are not part of the target genome [26].

- Primary Library Prep Cause: The most common cause is the presence of adapter dimers—short fragments composed only of adapter sequences that ligate to each other [27] [28] [13]. These non-informative sequences are amplified and sequenced, consuming flow cell space and generating unalignable data.

- Computational Impact: Adapter dimers force the alignment software to process millions of useless reads, drastically increasing analysis time and storage needs for temporary files. They also reduce the usable sequencing depth for the actual experiment.

- Solution:

- Optimize Size Selection: Perform a rigorous bead-based clean-up or gel extraction to remove fragments shorter than your intended insert size. A sharp peak at ~70-90 bp on a Bioanalyzer trace indicates adapter dimers [27] [13].

- Optimize Ligation Conditions: Ensure correct adapter-to-insert molar ratios to prevent adapter self-ligation. Use fresh, properly stored adapters [29].

- Use Trimming Tools: As a last resort, employ preprocessing tools like Cutadapt or Trimmomatic to identify and remove adapter sequences from the raw reads before alignment, though this adds an extra computational step [26].

FAQ 3: I see high variability in read depth across samples in my multiplexed run, forcing me to re-analyze data. How can this be prevented?

- Problem: Inconsistent read depth between samples in a pooled library leads to some targets being over-sequenced and others under-sequenced, compromising statistical power.

- Primary Library Prep Cause: Inaccurate library quantification and normalization prior to pooling. Manual quantification using absorbance methods and pipetting inaccuracies are frequent sources of error [13] [30].

- Computational Impact: Researchers must spend extra time and cloud computing credits to re-pool and re-sequence samples, or apply complex normalization algorithms during differential expression analysis (e.g., in DESeq2), which can introduce bias [26].

- Solution:

- Use qPCR for Quantification: Perform library quantification using qPCR-based kits (e.g., Ion Library Quantitation Kit) as they measure amplifiable molecules, which is what determines cluster generation on the sequencer [27].

- Automate Normalization: Implement automated liquid handling systems to improve pipetting precision and consistency during the normalization and pooling steps [29] [30].

- Use Auto-Normalizing Kits: Consider library prep kits that feature built-in normalization, which can maintain consistent read counts across a wide range of input concentrations [30].

Quantitative Guide: Library Prep Failures and Their Downstream Consequences

The table below summarizes how specific library preparation errors manifest in the data and their direct impact on the computational workflow.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide: Library Prep Errors and Downstream Computational Impact

| Library Prep Error | Observed Failure Signal | Downstream Computational Symptom | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adapter Dimer Formation [27] [13] | Sharp peak at ~70-90 bp on Bioanalyzer; Low alignment rate. | Wasted sequencing cycles; Increased processing time by aligners (BWA, HISAT2); Increased storage for useless data. | Optimize adapter ligation ratios; Implement rigorous bead-based size selection [29]. |

| Low Input/Degraded Sample [13] [30] | Low library yield; High duplication rate reported by tools like Picard. | Variant callers (GATK) process redundant data; Reduced statistical power; Increased false positives/negatives. | Verify input quality with fluorometry (Qubit); Use minimum required input DNA/RNA. |

| Over-amplification in PCR [13] | High duplication rate; Skewed fragment size distribution. | Increased computational burden in duplicate marking; Bias in variant calling and expression quantification. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles; Optimize amplification from ligation product [27]. |

| Inaccurate Library Normalization [30] | Uneven read depth across samples in a multiplexed run. | Requires re-sequencing or computational normalization in analysis (e.g., DESeq2), consuming extra time and cloud compute resources. | Use qPCR for quantification; Automate pooling with liquid handlers [29]. |

| Sample Contamination [30] | Presence of unexpected species or sequences in taxonomic profiling. | Complicates metagenomic analysis (Kraken, MetaPhlAn); Leads to misinterpretation of results and wasted analysis. | Use sterile techniques; Include negative controls; Re-purify samples with clean columns/beads [13]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Links

The following reagents and tools are critical for preventing the errors discussed above and ensuring a smooth transition to computational analysis.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Item | Function in Library Prep | Role in Mitigating Computational Load |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorometric Quantification Kits (e.g., Qubit) [13] | Accurately measures concentration of amplifiable nucleic acids, unlike UV absorbance. | Prevents low-complexity libraries, reducing duplicate reads and saving variant calling computation. |

| qPCR-based Library Quant Kits [27] | Precisely quantifies "amplifiable" library molecules before pooling. | Ensures even read depth across samples, avoiding the need for re-sequencing or complex data normalization. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Reduces errors during PCR amplification and enables fewer cycles. | Minimizes introduction of sequencing artifacts that must be filtered out during bioinformatic processing. |

| Robust Size Selection Beads [13] | Efficiently removes adapter dimers and selects for the desired insert size range. | Prevents generation of unalignable reads, streamlining the alignment process and improving usable data yield. |

| Automated Liquid Handlers (e.g., I.DOT) [29] [30] | Eliminates pipetting inaccuracies and variability in repetitive steps. | Reduces batch effects and normalization errors, leading to cleaner data that requires less corrective computation. |

Visual Workflow: How Library Prep Choices Ripple Through Data Analysis

The diagram below illustrates the cascading effect of library preparation quality on downstream computational processes, highlighting key bottlenecks.

Library Prep to Compute Impact Flow

In the context of large-scale NGS immunology research, the path to solving computational bottlenecks does not begin with more powerful servers or faster algorithms alone. It starts at the laboratory bench. By recognizing library preparation as the foundational step that dictates data quality, researchers can make strategic investments—in optimized protocols, precise quantification, and automation—that pay substantial dividends in computational efficiency [29] [30].

A disciplined approach to library prep reduces wasted sequencing cycles, minimizes the need for complex data correction, and ensures that the powerful computational tools for variant calling, differential expression, and metagenomic analysis are operating on the cleanest possible data. This synergy between wet-lab practice and dry-lab analysis is the key to accelerating drug development and unlocking meaningful biological insights from immunogenomic data.

Technical Support Center

HLA Typing: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: My HLA typing results from NGS data show low coverage for certain exons. What could be the cause and how can I resolve it?

A: Low coverage in specific exons, particularly in HLA Class II genes, is a common computational bottleneck. This is often due to high sequence similarity between HLA alleles and the presence of intronic regions.

- Cause: Misalignment of sequencing reads to the incorrect reference genome or a reference that lacks comprehensive HLA allele diversity.

- Solution:

- Use an HLA-Optimized Aligner: Switch from a general-purpose aligner (like BWA) to a specialized tool (e.g.,

HLAminer,Kourami,OptiType). These tools use a graph-based or allele-specific approach to handle high polymorphism. - Employ an HLA-Enhanced Reference: Use a reference panel that includes a wide array of known HLA sequences (e.g., the IPD-IMGT/HLA database) to improve mapping accuracy.

- Check Primer Binding Sites: If using amplicon-based sequencing, validate that your primer sequences are not overlapping with known polymorphisms that could cause amplification bias.

- Use an HLA-Optimized Aligner: Switch from a general-purpose aligner (like BWA) to a specialized tool (e.g.,

Q2: How do I interpret the ambiguity in my HLA typing output, such as a result listed as "HLA-A*02:01:01G"?"

A: Ambiguity arises when different combinations of polymorphisms across the gene yield identical sequencing reads for the exons tested.

- Interpretation: "G" groups (e.g.,

*02:01:01G) represent alleles that are identical in their peptide-binding regions (exons 2 and 3 for Class I; exon 2 for Class II). For most functional studies, this level of resolution is sufficient. - Resolution: To resolve "field" ambiguities (e.g.,

*02:01vs*02:05), you need:- Wet-Lab: Phase-separated sequencing (e.g., long-read sequencing) to determine which polymorphisms are on the same chromosome.

- In-Silico: Use computational phasing tools that leverage read-pair information or population-based haplotype frequencies.

Experimental Protocol: High-Resolution HLA Typing from Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) Data

- Data Input: Paired-end WGS reads (FASTQ format).

- Quality Control: Use

FastQCandTrimmomaticto assess and trim adapter sequences and low-quality bases. - Alignment & Typing:

- Execute

Kouramiwith its bundled HLA reference graph. - Command:

java -jar Kourami.jar -r <reference_dir> -s <sample_id> -o <output_dir> <input_bam_file>

- Execute

- Result Interpretation: The output provides the most likely 4-digit (or higher) HLA alleles. Cross-reference the reported alleles with the IPD-IMGT/HLA database for functional annotation.

HLA Typing from WGS Data

TCR/BCR Repertoire: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: My TCR/BCR repertoire analysis shows a very low diversity index. Is this a technical artifact or a true biological signal?

A: It can be either. Systematic errors must be ruled out before biological interpretation.

Technical Causes & Solutions:

- Low Input DNA/RNA: Increases stochastic PCR bias. Use a quantitative method (e.g., Qubit, Bioanalyzer) to ensure sufficient starting material.

- PCR Over-Amplification: Leads to dominance by a few high-abundance clones. Optimize PCR cycle number and use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to correct for amplification bias.

- Bioinformatic Preprocessing: Inadequate quality filtering or primer trimming can remove valid reads. Re-inspect raw read quality and adjust preprocessing parameters.

Biological Signal: A low diversity index is a valid finding in contexts like acute immune response, immunosenescence, or certain immunodeficiencies.

Q2: How can I accurately track the same T-cell or B-cell clone across multiple time points or tissues?

A: This requires high-specificity clonotype tracking.

- Method: Use the CDR3 nucleotide sequence as the clone identifier, as it is the most specific marker.

- Computational Protocol:

- UMI Deduplication: For each sample, group reads by UMI and assemble a consensus CDR3 sequence to eliminate PCR and sequencing errors.

- Clonotype Definition: Define clonotypes based on identical CDR3 amino acid sequences and V/J gene assignments.

- Cross-Sample Comparison: Use a tool like

alakazamorscRepertoire(for single-cell data) to calculate clonotype overlap and abundance across samples.

Experimental Protocol: TCRβ Repertoire Sequencing with UMIs

- Library Prep: Use a multiplex PCR system (e.g., Adaptive Biotechnologies' ImmunoSEQ, iRepertoire) with primers containing UMIs.

- Sequencing: High-throughput sequencing on an Illumina platform (2x150bp or 2x250bp recommended).

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- UMI Extraction & Error Correction: Use

pRESTOorMiGECto group reads by UMI and generate consensus sequences. - V(D)J Assignment: Align consensus sequences to a V(D)J reference using

IgBLASTorMiXCR. - Clonotype Table Generation: Collapse identical CDR3aa + V + J combinations to create a frequency table.

- UMI Extraction & Error Correction: Use

TCR Rep Sequencing with UMIs

V(D)J Analysis: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: My V(D)J rearrangement analysis from single-cell RNA-seq data has a low cell recovery rate. What are the key parameters to check?

A: Low cell recovery is often due to suboptimal data processing.

- Key Parameters:

- Cell Barcodes: Ensure the correct barcode whitelist and barcode length are specified. Low-quality bases at the start of Read 1 can cause barcode misidentification.

- Read Orientation: Confirm that the sequence of the constant region primer is correctly specified and that the tool is searching for it on the correct strand.

- Alignment Confidence: Increase the

--expect-cellsparameter inCell Ranger vdjif you loaded more cells than the default (e.g., 10,000), or adjust the alignment scoring thresholds in other tools.

Q2: How can I visualize the clonal relationships and somatic hypermutation (SHM) in my B-cell data?

A: This requires constructing lineage trees.

- Method:

- Data Extraction: For a clone of interest, extract all heavy-chain sequences (germline-aligned VDJ sequences and their UMIs/counts).

- Germline Reconstruction: Infer the unmutated common ancestor sequence using a tool like

IgPhyMLorpartis. - Tree Building: Input the germline sequence and the mutated sequences into a phylogenetic tree builder (e.g,

PHYLIP,dnaml) that can handle high mutation rates.

Experimental Protocol: Single-Cell V(D)J and Gene Expression Analysis (10x Genomics)

- Library Preparation: Generate both 5' Gene Expression and V(D)J libraries from the same single-cell suspension following the manufacturer's protocol.

- Sequencing: Sequence libraries on an Illumina NovaSeq or HiSeq.

- Data Processing:

- Run

Cell Ranger multito simultaneously analyze both libraries, using the--feature-reffile to link the two datasets. - This produces a unified feature-barcode matrix containing clonotype information for each cell barcode.

- Run

- Downstream Analysis: In R, use the

SeuratandscRepertoirepackages to integrate clonality with cluster phenotypes and perform trajectory analysis on expanded clones.

Single-Cell V(D)J + GEX Workflow

Table 1: Comparison of HLA Typing Tools (Theoretical Performance on WGS Data)

| Tool | Algorithm Type | Required Read Length | Reported 4-Digit Accuracy | Key Computational Bottleneck |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kourami | Graph-based alignment | >= 100bp | >99% | High memory usage for graph construction |

| OptiType | Integer Linear Programming | >= 50bp | >97% | Limited to HLA Class I genes |

| HLAminer | Read alignment & assembly | >= 150bp | >95% | Long runtime for assembly step |

| PolySolver | Bayesian inference | >= 100bp | >96% | Sensitivity to alignment errors |

Table 2: Key Metrics for TCR Repertoire Quality Control

| Metric | Acceptable Range | Indication of Problem |

|---|---|---|

| Reads per Clone | Even distribution, long tail | A few clones with extremely high counts indicate PCR bias. |

| Clonotype Diversity (Shannon) | Context-dependent | Very low diversity may indicate technical bottlenecking. |

| UMI Saturation | >80% | Lower values suggest insufficient sequencing depth. |

| In-Frame Rearrangements | >85% of productive clones | Lower rates suggest poor RNA quality or bioinformatic errors. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents & Tools for NGS Immunology

| Item | Function | Example Product/Software |

|---|---|---|

| UMI Adapters | Tags each original molecule with a unique barcode to correct for PCR and sequencing errors. | NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina |

| Multiplex PCR Primers | Amplifies all possible V(D)J rearrangements in a single reaction from bulk cells. | iRepertoire Human TCR/BCR Primer Sets |

| Single-Cell Barcoding Kit | Labels cDNA from individual cells with a unique barcode for cell-specific V(D)J recovery. | 10x Genomics Single Cell 5' Kit |

| HLA Allele Database | Reference set for accurate alignment and typing of highly polymorphic HLA genes. | IPD-IMGT/HLA Database |

| V(D)J Reference Set | Curated database of germline V, D, and J gene segments for alignment. | IMGT Reference Directory |

| Specialized Aligner | Software optimized for resolving complex, hypervariable immune sequences. | MiXCR, IgBLAST |

Advanced Computational Methods for NGS Immunology Data

Machine Learning Integration for Multimodal Immunological Data

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized immunology research by enabling high-throughput analysis of immune repertoires, cell states, and functions. However, the integration of multimodal immunological data—spanning genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and clinical information—presents significant computational challenges that form the central bottleneck in large-scale NGS immunology research. The convergence of artificial intelligence (AI) with NGS technologies offers transformative potential to overcome these hurdles, accelerating the pace from data generation to biological insight and clinical application [31] [32].

This technical support center addresses the specific computational and methodological challenges researchers encounter when implementing machine learning for multimodal immunological data analysis. The guidance provided is framed within the broader thesis that strategic computational approaches can effectively resolve these bottlenecks, enabling robust, reproducible, and clinically actionable findings in immunology.

Troubleshooting Guides: Resolving Critical Bottlenecks

Data Quality and Preprocessing Issues

Problem: Sequencing Errors and Quality Control Failures Sequencing errors in NGS data can introduce false variants and significantly impact downstream ML model performance. In immunology, this is particularly critical when analyzing B-cell or T-cell receptor repertoires where single nucleotide variations can alter receptor specificity [1].

Solutions:

- Implement Robust QC Pipelines: Use tools like FastQC and MultiQC for comprehensive quality assessment. Establish strict quality thresholds based on your specific immunological application.

- AI-Enhanced Error Correction: Employ ML tools like DeepVariant which uses deep learning to distinguish true genetic variants from sequencing errors, significantly improving accuracy over traditional methods [31] [32].

- Batch Effect Correction: Utilize combat-like algorithms or neural network approaches (e.g., VAEs) to remove technical artifacts while preserving biological signals, especially crucial when integrating data from multiple experiments or time points.

Table 1: Quality Control Metrics and Thresholds for NGS Immunology Data

| Metric | Optimal Range | Threshold for Concern | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phred Quality Score | ≥Q30 for >80% bases | Trimming, filtering, or resequencing | |

| Read Depth (Immunology Panels) | 500-1000x | <200x | Increase sequencing depth |

| Duplication Rate | <10-20% | >50% | Optimize library preparation |

| Base Balance | Even across cycles | Significant bias | Check sequencing chemistry |

Problem: Data Heterogeneity and Integration Challenges Multimodal immunology data often comes from diverse sources—genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and clinical—each with different scales, distributions, and missing data patterns [33] [34].

Solutions:

- Cross-Modal Imputation: Use neural network architectures (e.g., autoencoders) specifically designed for imputing missing data across modalities while preserving biological relationships.

- Harmonization Techniques: Implement MNN (Mutual Nearest Neighbors) or deep learning-based alignment methods when integrating datasets from different batches, technologies, or institutions.

- Feature Standardization: Apply modality-specific normalization (e.g., CPM for RNA-seq, arcsinh for CyTOF) before integration to maintain technical consistency.

Model Training and Performance Issues

Problem: Poor Model Generalization Despite High Training Accuracy Immunology datasets often suffer from high dimensionality with relatively small sample sizes, leading to overfitting despite apparent good performance during training [35] [36].

Solutions:

- Regularization Strategies: Implement L1/L2 regularization, dropout in neural networks, or ensemble methods like Random Forests which are naturally robust to overfitting.

- Cross-Validation Protocols: Use nested cross-validation with appropriate stratification to account for cohort effects in immunological studies.

- Data Augmentation: For image-based immunology data (e.g., histopathology), employ rotation, flipping, and color variations. For sequence data, consider synthetic minority oversampling or generative adversarial networks (GANs) to create realistic synthetic data [32].

Problem: Model Interpretability Barriers in Clinical Translation The "black box" nature of complex ML models hinders clinical adoption in immunology, where understanding biological mechanisms is as important as prediction accuracy [33] [37].

Solutions:

- Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques: Implement SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) to quantify feature importance.

- Attention Mechanisms: Use transformer models with built-in attention layers that can highlight relevant sequence regions or cell populations driving predictions.

- Biological Validation: Always correlate ML-derived features with known immunological pathways and validate findings through experimental follow-up.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks for ML Models on Immunology Tasks

| Model Type | Typical Accuracy Range | Best For Immunology Use Cases | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 75-92% | Patient stratification, biomarker discovery | Medium (feature importance) |

| XGBoost | 78-95% | Treatment response prediction | Medium (feature importance) |

| Neural Networks | 82-97% | Image analysis, sequence modeling | Low (requires XAI) |

| Transformer Models | 85-98% | Immune repertoire analysis | Medium (attention weights) |

Computational Infrastructure Limitations

Problem: Processing Delays with Large-Scale Immunology Datasets Multimodal immunology datasets, especially single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, can reach terabytes in scale, overwhelming conventional computational resources [1] [32].

Solutions:

- Federated Learning: Implement privacy-preserving distributed ML approaches that train models across multiple institutions without sharing raw patient data, crucial for multi-center immunology studies [31].

- Cloud and HPC Utilization: Leverage GPU acceleration (NVIDIA Parabricks) which can accelerate genomic analyses by up to 80x compared to CPU-based workflows [32].

- Progressive Analysis: Implement stochastic gradient methods that process data in mini-batches rather than loading entire datasets into memory.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What machine learning approach works best for integrating genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data in immunology studies?

Multimodal AI approaches that combine multiple data types consistently outperform single-data models, showing an average 6.4% increase in predictive accuracy [38]. The optimal architecture depends on your specific research question:

- Early Fusion: Combine raw data from multiple modalities before feature extraction when modalities are highly correlated.

- Intermediate Fusion: Use separate feature extractors for each modality with a shared integration layer (e.g., multimodal autoencoders).

- Late Fusion: Train separate models on each modality and combine predictions, ideal when modalities have different statistical properties.

For immunology applications, intermediate fusion with dedicated neural network encoders for each data type typically performs best, allowing the model to learn both modality-specific and cross-modal representations [33] [34].

Q2: How can we address the 'small n, large p' problem in immunological datasets where we have many more features than samples?

This high-dimensionality challenge is common in immunology research. Several strategies have proven effective:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Use UMAP or t-SNE for visualization, but employ PCA or autoencoders for feature reduction before model training.

- Feature Selection: Prioritize biologically informed feature selection (e.g., known immune pathways) before applying ML, or use regularized models (Lasso, Elastic Net) that perform implicit feature selection.

- Transfer Learning: Leverage pre-trained models on larger public datasets (e.g., ImmPort, TCGA) and fine-tune on your specific immunology dataset [36].

- Data Augmentation: Carefully apply synthetic data generation techniques, particularly for immune repertoire sequencing data where legitimate sequence variations can be modeled.

Q3: What are the best practices for validating ML models in immunology to ensure findings are biologically meaningful and reproducible?

Robust validation is crucial for immunological applications:

- External Validation: Always validate models on completely independent cohorts, ideally from different institutions or collected using different protocols.

- Biological Plausibility Check: Ensure model predictions align with established immunological knowledge; use pathway enrichment analysis on important features.

- Experimental Validation: Design flow cytometry, functional assays, or animal models to test key predictions from your ML models.

- Benchmarking: Compare performance against established immunological benchmarks and traditional statistical methods to demonstrate added value [35].

Q4: How can we effectively handle missing data across multiple modalities in immunology datasets?

Missing data is common in multimodal studies. The optimal approach depends on the missingness mechanism:

- ML-Based Imputation: Use sophisticated imputation methods like MICE (Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations) or neural network approaches (GAIN) for data missing at random.

- Model-Level Handling: Employ algorithms like XGBoost that naturally handle missing values, or use mask-based approaches in neural networks.

- Strategic Exclusion: For modalities with >40% missingness, consider excluding that modality entirely rather than relying on highly imputed data.

Q5: What computational resources are typically required for large-scale immunology ML projects?

Requirements vary by project scale:

- Moderate Scale (Single-cell RNA-seq of 10,000-100,000 cells): 16-32 CPU cores, 64-128GB RAM, potential GPU acceleration (NVIDIA V100 or A100).

- Large Scale (Population immunology, millions of cells): High-performance computing clusters, specialized genomic databases, cloud computing solutions with distributed processing capabilities [1] [32].

Table 3: Computational Requirements for Common Immunology ML Tasks

| Analysis Type | Recommended RAM | CPU Cores | GPU | Storage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk RNA-seq DE Analysis | 16-32GB | 8-16 | Optional | 50-100GB |

| Single-cell RNA-seq (10k cells) | 32-64GB | 16-32 | Recommended | 100-200GB |

| Immune Repertoire Sequencing | 64-128GB | 16-32 | Highly Recommended | 200-500GB |

| Multimodal Integration (3+ modalities) | 128GB+ | 32+ | Essential | 500GB-1TB+ |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: ML-Driven Immune Response Prediction

Objective: Predict response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy using integrated multimodal data [34].

Materials and Methods:

- Data Collection:

- Collect pre-treatment tumor samples with matched genomic (WES/WGS), transcriptomic (RNA-seq), and clinical data

- Include at least 50 responders and 50 non-responders for statistical power

Feature Engineering:

- Genomic Features: Calculate tumor mutation burden, neoantigen load, specific mutation status (e.g., POLE, POLD1)

- Transcriptomic Features: Compute immune cell scores (using CIBERSORTx), gene expression signatures (IFN-γ, expanded-immune signature)

- Clinical Features: Include PD-L1 expression, tumor stage, previous treatments

Model Training:

- Implement ensemble methods (Random Forest, XGBoost) as baseline

- Compare with neural network architectures specifically designed for multimodal integration

- Use 5-fold cross-validation with stratification by response status

Validation:

- Validate on independent cohort with same data modalities

- Perform permutation testing to assess significance

- Use SHAP analysis to identify most predictive features

Protocol: Automated Variant Reporting in Immunology

Objective: Implement ML-based clinical decision support for variant reporting in immunology-related genes [37].

Materials and Methods:

- Data Curation:

- Collect historical variant calls with expert curation labels (reportable vs. not reportable)

- Include at least 1,000 variants with ground truth classifications

- Extract 200+ features per variant including functional prediction scores, population frequency, conservation scores

Model Development:

- Train tree-based ensemble models (Random Forest, XGBoost) which have shown excellent performance (PRC AUC 0.891-0.995)

- Implement neural networks for comparison

- Address class imbalance using SMOTE or weighted loss functions

Interpretability Implementation:

- Integrate SHAP values or LIME for explainable predictions

- Create waterfall plots showing feature contributions for each variant

- Establish confidence thresholds for automated vs. manual review

Clinical Integration:

- Deploy as part of tertiary analysis platform

- Implement continuous learning from expert feedback

- Maintain audit trail of all automated decisions

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML in Immunology

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application in Immunology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio Revio, Oxford Nanopore | High-throughput data generation | Immune repertoire sequencing, single-cell immunology |

| Data Analysis Suites | Illumina BaseSpace, DNAnexus, Lifebit | Cloud-based NGS analysis | Multimodal data integration without advanced programming |

| Variant Calling | DeepVariant, GATK, NVIDIA Parabricks | Accurate variant identification | Somatic variant detection in cancer immunology |

| Single-cell Analysis | Cell Ranger, Seurat, Scanpy | Processing single-cell data | Immune cell atlas construction, cell state identification |

| ML Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn | Model development and training | Predictive model building for immune responses |

| Immunology-Specific DB | ImmPort, VDJerry, ImmuneCODE | Reference data repositories | Training data for immune-specific models |

| Visualization Tools | UCSC Genome Browser, Cytoscape, UMAP/t-SNE | Data exploration and presentation | Immune repertoire dynamics, cell population visualization |

Advanced Methodologies and Future Directions

Emerging Approaches: Federated Learning for Multi-Center Immunology Studies

Federated learning enables collaborative model training across institutions without sharing sensitive patient data, addressing critical privacy concerns in immunology research [31]. This approach is particularly valuable for:

- Rare Immune Disorders: Pooling knowledge across multiple centers to overcome small sample sizes

- Global Health Immunology: Studying population-specific immune responses while maintaining data sovereignty

- Clinical Trial Optimization: Developing predictive models using data from multiple trial sites without centralizing data

Implementation requires specialized platforms (e.g., Lifebit, NVIDIA FLARE) and careful attention to data harmonization across sites to ensure model robustness.

Third-Generation Sequencing Integration

Long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) present new opportunities and challenges for immunological research:

- Complete Immune Receptor Characterization: Sequencing full-length B-cell and T-cell receptors without assembly

- Epigenetic Modifications: Direct detection of methylation patterns in immune cells using Nanopore sequencing

- Integrated Multiomics: Simultaneous measurement of transcriptome and epigenome from the same cell

AI approaches are evolving to handle the unique characteristics of third-generation sequencing data, including higher error rates that require specialized basecalling models and error correction algorithms [31] [9].

Through systematic implementation of these troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and computational strategies, researchers can effectively overcome the bottlenecks in large-scale NGS immunology research, accelerating the translation of multimodal data into immunological insights and therapeutic advances.

This technical support center addresses common challenges in analyzing large-scale Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) data for immunology research. The following guides provide solutions for persistent computational bottlenecks.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary purpose of ImmunoDataAnalyzer? ImmunoDataAnalyzer (IMDA) is a bioinformatics pipeline that automates the processing of raw NGS data into analyzable immune repertoires. It covers the entire workflow from initial quality control and clonotype assembly to the comparison of multiple T-cell receptor (TCR) and immunoglobulin (IG) repertoires, facilitating the calculation of clonality, diversity, and V(D)J gene segment usage [39].

2. My analysis pipeline failed with an error about a missing endogenous control. What does this mean? This error typically occurs due to a configuration conflict between singleplex and multiplex experiment data within an analysis group. To resolve it, you can either: a) separate the singleplex and multiplex data into distinct analysis groups, or b) configure the current analysis group to skip target normalization [40].

3. I am seeing a high fraction of cells with zero transcripts in my single-cell data. What could be the cause? An unusually high fraction of empty cells can be caused by two main issues. First, the gene panel used may not contain genes expressed by a major cell type in your sample. Second, it could indicate poor cell segmentation. It is recommended to verify that your gene panel is well-matched to the sample and then use visualization tools to inspect the accuracy of cell boundaries [41].

4. How can I handle the massive computational demands of NGS data analysis? Large datasets from whole-genome or transcriptome studies require powerful, optimized workflows. Proven solutions include using efficient data formats (like Parquet), high-performance tools like MiXCR, and leveraging scalable computational environments like cloud platforms (AWS, GCP, Azure) or high-performance computing (HPC) clusters. User-friendly interfaces are also making these powerful resources more accessible to biologists [2] [1] [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Pipeline Configuration and Input Errors

| Alert/Issue | Possible Cause | Suggested Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Missing Endogenous Control [40] | Conflict between singleplex analysis settings and multiplex data. | Create separate analysis groups for singleplex and multiplex data, or configure the group to "Skip target normalization". |

| Incorrect Gene Panel [41] | Wrong gene_panel.json file selected during run setup, or incorrect probes added to the slide. |

Verify the panel file and probes used. Re-run the relabeling tool (e.g., Xenium Ranger) with the correct panel. |

| Poor Quality Imaging Cycles [41] | Algorithmic failure, instrument error, very low sample quality/ complexity, or sample handling problems. | Inspect the Image QC tab to identify cycles/channels with missing data or artifacts. Contact technical support to rule out instrument errors. |

Data Quality and Output Alerts

| Alert/Issue | Metric & Thresholds | Investigation & Actions |

|---|---|---|

| High Fraction of Empty Cells [41] | Error: >10% of cells have 0 transcripts. | 1. Check if the gene panel matches the sample's expected cell types.2. Visually inspect cell segmentation accuracy and try re-segmentation if needed. |

| Low Fraction of High-Quality Transcripts [41] | Warning: <60%Error: <50% of gene transcripts are high quality (Q20). | Often linked to poor sample quality, low complexity, or high transcript density (e.g., in tumors). Contact technical support for diagnostics. |

| High Negative Control Probe Counts [41] | Warning: >2.5%Error: >5% counts per control per cell. | Could indicate assay workflow issues (e.g., incorrect wash temperature) or poor sample quality. Check if a few specific probes are high and exclude them. |

| Low Decoded Transcript Density [41] | Warning: <10 transcripts/100µm² in nuclei.Error: <1 transcript/100µm². | Top causes: low RNA content, over/under-fixation (FFPE), or evaporation during sample handling. Investigate tissue integrity and RNA quality. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

ImmunoDataAnalyzer (IMDA) Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the automated IMDA pipeline for processing raw NGS data into analyzed immune repertoires [39].

Key Steps:

- Input: The pipeline begins with raw NGS reads from barcoded and Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) tagged immunological data [39].

- Pre-processing & QC: MIGEC performs initial quality control, de-multiplexing, and UMI consensus assembly to ensure data quality and correct read assignment [39].

- Clonotype Assembly: MiXCR maps reads to reference genes, identifies, and quantifies clonotypes. Clonotypes are defined by identical CDR3 amino acid sequences and V/J gene pairings [39].

- Analysis: VDJtools performs advanced analysis, calculating diversity indices, clonality measures, V(D)J gene usage, and sample similarities [39].

- Output: The pipeline generates a compact summary with visualizations and a machine learning-ready file for further predictive modeling [39].

Troubleshooting Logic for Common Alerts

When encountering data quality alerts, follow a systematic investigation path.

Investigation Steps:

- Verify Experimental Setup: Always first confirm that the correct gene panel was used and that it is appropriate for the sample type. An incorrect panel is a common root cause [41].

- Inspect Algorithmic Output: Use visualization software to check the accuracy of foundational steps like cell segmentation. Inaccurate boundaries can lead to misleading metrics [41].

- Review Sample Quality: Investigate wet-lab procedures. Poor RNA quality, over-fixation, or errors during master mix preparation are frequent culprits behind low transcript counts or quality [41] [1].

- Escalate: If the above checks do not identify the problem, contact technical support to rule out instrument errors or algorithmic failures [41] [42].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| BD Rhapsody Cartridges [43] | Single-cell partitioning system for capturing individual cells and barcoding molecules. |

| BD OMICS-Guard [43] | Reagent for the preservation of single-cell samples to maintain RNA integrity before processing. |

| BD AbSeq Oligos [43] | Antibody-derived tags for quantifying cell surface and intracellular protein expression via sequencing (CITE-Seq). |

| BD Single-Cell Multiplexing Kit (SMK) [43] | Allows sample multiplexing by labeling cells from different sources with distinct barcodes, reducing batch effects and costs. |

| BD Rhapsody WTA & Targeted Panels [43] | Beads and reagents for Whole Transcriptome Analysis or targeted mRNA capture for focused gene expression studies. |

| Immudex dCODE Dextramer [43] | Reagents for staining T-cells with specific TCRs, enabling the analysis of antigen-specific immune responses. |

Advanced Support: Bridging Computational Bottlenecks

The field of computational immunology faces several persistent bottlenecks that tools like ImmunoDataAnalyzer aim to solve [39] [19].

- Data Volume and Complexity: NGS technologies generate terabytes of data, requiring resource-intensive pipelines. Solutions include using efficient data formats, high-performance tools like MiXCR, and leveraging cloud or high-performance computing (HPC) resources [2] [19].

- Standardization and Reproducibility: Variability in analysis tools and a lack of standardized protocols can lead to conflicting results. Adopting community-validated, containerized workflows (e.g., using Docker, Nextflow) ensures consistency and reproducibility across studies [1] [19].

- Multi-omics Integration: Combining data from genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics is complex. Using specialized integration frameworks (e.g., MOFA, Seurat) is essential to derive unified biological insights [19].

For further assistance, do not hesitate to use official support channels, including web forms, phone, and live chat, provided by companies like BD Biosciences [42] and 10x Genomics [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between PCA, t-SNE, and UMAP for cytometry data analysis?

A: These algorithms differ significantly in their mathematical approaches and the data structures they preserve:

PCA (Principal Component Analysis): A linear dimensionality reduction method that projects data onto directions of maximum variance. It excels at preserving global structure and relationships between distant clusters but may miss complex nonlinear patterns. PCA is computationally efficient and provides interpretable components but is less effective for visualizing complex cell populations in cytometry data [44] [45] [46].

t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding): A non-linear technique that primarily preserves local structure by maintaining relationships between nearby points. It effectively reveals cluster patterns but does not preserve global geometry (distances between clusters are meaningless). t-SNE is computationally intensive and can be sensitive to parameter choices [47] [45] [46].

UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection): Also a non-linear method that aims to preserve both local and more global structure better than t-SNE. It has faster runtimes and is argued to better maintain distances between cell clusters. However, like t-SNE, it can produce artificial separations and remains sensitive to parameter settings [47] [45] [46].

Q2: When should I use t-SNE over UMAP, and vice versa, for high-dimensional cytometry data?

A: The choice depends on your analytical priorities and data characteristics:

Choose t-SNE when: You prioritize identifying clear, separate clusters of similar cell types and are less concerned with relationships between these clusters. t-SNE demonstrates excellent local structure preservation, making it robust for identifying distinct cell populations in complex immunology datasets [48] [45] [46].

Choose UMAP when: You need faster processing of large datasets (particularly beneficial for massive cytometric data) and want to better visualize relationships between clusters. UMAP generally provides better preservation of global structure while still maintaining local neighborhood relationships [47] [45].

Recent benchmarking on cytometry data has revealed that t-SNE possesses the best local structure preservation, while UMAP excels in downstream analysis performance. However, significant complementarity exists between tools, suggesting the optimal choice should align with specific analytical needs and data structures [48].

Q3: What are the key parameters I need to optimize for t-SNE and UMAP in cytometry analysis?

A: Proper parameter tuning is essential for meaningful results:

t-SNE Key Parameters:

UMAP Key Parameters:

Both methods are sensitive to these parameter choices, which can dramatically alter visualization results. Systematic parameter exploration is recommended, especially when analyzing unfamiliar datasets [46].

Q4: How can I quantitatively evaluate and compare different dimensionality reduction results for my cytometry data?

A: Several quantitative metrics can objectively assess dimensionality reduction quality:

Local Structure Preservation: Measure how well local neighborhoods from high-dimensional space are preserved in the low-dimensional embedding. The fraction of nearest neighbors preserved is an effective unsupervised metric for this purpose [46].

Global Structure Preservation: Evaluate whether relative positions between major cell populations or developmental trajectories are maintained. The Pearson correlation between pairwise distances in high-dimensional and low-dimensional spaces can quantify this [49].

Cluster Quality Metrics: Silhouette scores can measure how well separated and compact identified cell populations appear in the reduced space [49].

Biological Concordance: For cytometry data, assess whether the visualization aligns with known immunology and cell lineage relationships [48].

Cross Entropy Test: A recently developed statistical approach specifically for comparing t-SNE and UMAP projections that uses the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test on cross entropy distributions, providing a robust distance metric between single-cell datasets [47].

Q5: What are common pitfalls when interpreting t-SNE and UMAP visualizations?