Small Molecule Inhibitors for Dendritic Cell Generation from Bone Marrow: Mechanisms, Methods, and Therapeutic Applications

This comprehensive review explores the innovative use of small molecule inhibitors to generate and mature dendritic cells (DCs) from bone marrow precursors, a rapidly advancing field in cancer immunotherapy and...

Small Molecule Inhibitors for Dendritic Cell Generation from Bone Marrow: Mechanisms, Methods, and Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the innovative use of small molecule inhibitors to generate and mature dendritic cells (DCs) from bone marrow precursors, a rapidly advancing field in cancer immunotherapy and regenerative medicine. We examine the foundational biology of DC development and the mechanistic roles of key signaling pathways targeted by inhibitor cocktails. The article provides detailed methodological insights into optimized culture protocols, including the YPPP cocktail (Y27632, PD0325901, PD173074, PD98059) and other emerging compounds. We address critical troubleshooting considerations for enhancing DC yield and functionality, while presenting robust validation frameworks through phenotypic characterization, functional assays, and comparative analyses with traditional cytokine-based methods. Finally, we discuss translational applications in cancer vaccines and combination immunotherapies, offering researchers and drug development professionals a strategic roadmap for implementing these cutting-edge techniques.

DC Biology and Small Molecule Targeting Rationale

Dendritic Cell Subsets and Developmental Pathways from Bone Marrow

Dendritic cells (DCs) are professional antigen-presenting cells that play a central role in regulating immune responses by linking innate and adaptive immunity [1]. Since their discovery by Ralph Steinman and Zanvil Cohn in 1973, research has revealed substantial diversity in DC origins, developmental pathways, and functional specializations [1]. DCs originate from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the bone marrow and develop into distinct subsets under precise transcriptional and cytokine regulation [1] [2].

Understanding DC ontogeny and subset heterogeneity is crucial for developing DC-based immunotherapies. Recent advances demonstrate that small molecule inhibitors can effectively modulate DC development and function, offering promising tools for research and therapeutic applications [3] [4]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of DC subsets, their developmental pathways from bone marrow, and detailed protocols for generating DCs using small molecule inhibitors.

DC Ontogeny and Subset Classification

Dendritic cells arise from hematopoietic stem cells through several progenitor stages, including macrophage-DC progenitors (MDPs) and common DC progenitors (CDPs) [3] [2]. The cytokine Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3L) plays a pivotal role in DC development, driving the differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells into multiple DC subsets [2]. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) promotes the development of monocyte-derived DCs (moDCs), particularly during inflammation [2].

Table 1: Major Dendritic Cell Subsets and Their Characteristics

| Subset | Key Markers (Human/Mouse) | Primary Functions | Localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| cDC1 | CD11c, MHC-II, XCR1, Clec9A, CADM1 (human: CD141/BDCA3) | Cross-presentation of antigens to CD8+ T cells, Th1 immunity, anti-tumor responses | Lymphoid tissues, peripheral tissues, blood |

| cDC2 | CD11c, MHC-II, CD11b, SIRPα (human: CD1c) | Presentation of antigens to CD4+ T cells, Th2/Th17 responses | Lymphoid tissues, peripheral tissues, blood |

| pDC | CD123, BDCA2, BDCA4, low CD11c | Type I interferon production, antiviral immunity | Blood, lymphoid organs |

| moDC | CD11c, MHC-II, CD14, CD11b | Inflammatory responses, antigen presentation during infection | Inflammatory sites |

| LC | Langerin, CD1a, E-cadherin | Antigen capture in epithelial barriers, immune surveillance | Epidermis, mucosal epithelia |

| tDC | CD11c, CD172a, Flt3, CD123 (porcine model) | Proposed role in immune regulation, transitional state | Blood, lymphoid tissues |

| DC3 | CD163, CD14, S100A8/9 (human); CD11c, CD172a (porcine) | Inflammatory responses, T cell polarization | Inflammatory sites, blood |

DC development is regulated by specific transcription factors. cDC1 differentiation requires IRF8, BATF3, and ID2, while cDC2 development depends on IRF4 and ZEB2 [2]. Plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) develop through mechanisms involving E proteins, RUNX1, and IRF8 [2]. Recent single-cell RNA sequencing studies have revealed additional heterogeneity within DC populations, identifying novel subsets such as transitional DCs (tDCs) and DC3s, which exhibit features intermediate between classical DCs and monocytes [5].

Signaling Pathways in DC Development

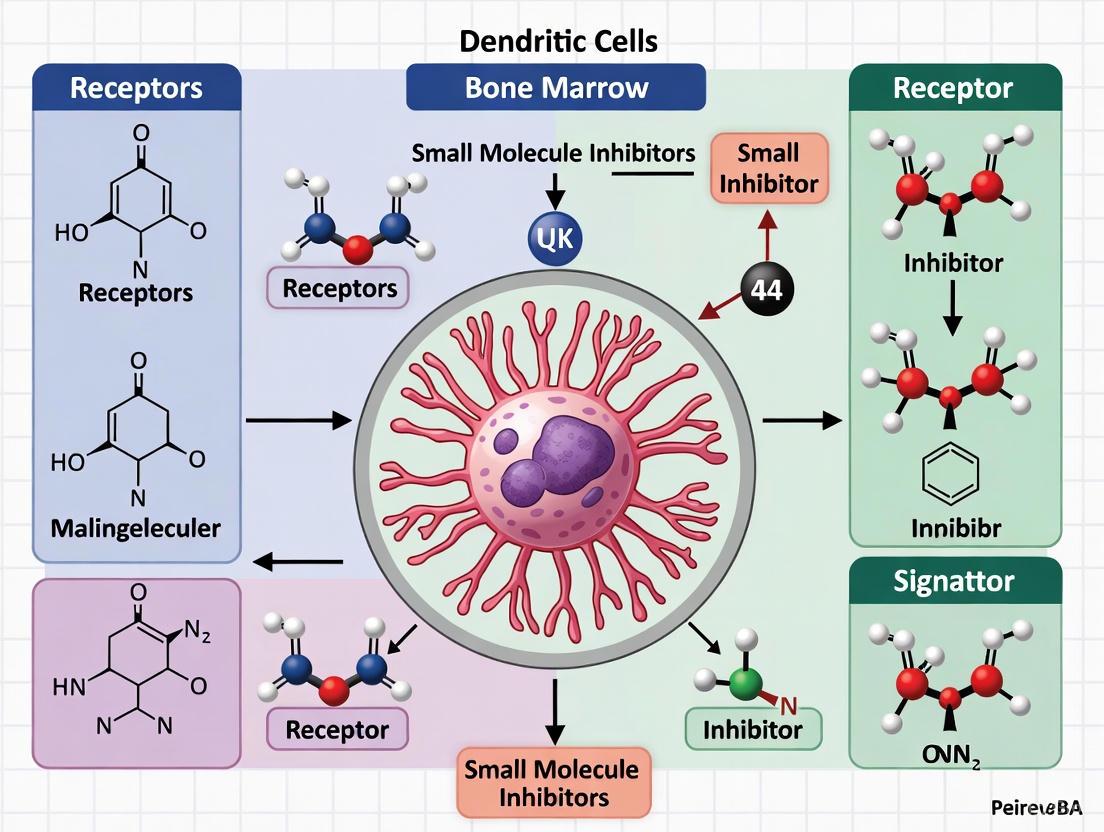

The development of dendritic cells from bone marrow precursors is governed by coordinated signaling pathways that determine subset specification and functional maturation. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways and transcriptional regulators involved in DC development:

Figure 1: DC Development Signaling Pathways. This diagram illustrates the key cytokine signals, transcription factors, and small molecule inhibitors that regulate the development of dendritic cell subsets from bone marrow precursors. The YPPP small molecule inhibitor cocktail (Y27632, PD0325901, PD173074, and PD98059) promotes DC maturation in GM-CSF cultures [3] [4].

Experimental Protocol: Generating DCs with Small Molecule Inhibitors

Background and Principle

This protocol describes a method to generate dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow using GM-CSF and a cocktail of four small molecule inhibitors (YPPP): Y27632 (ROCK inhibitor), PD0325901 (MEK inhibitor), PD173074 (FGFR inhibitor), and PD98059 (MEK inhibitor) [3] [4]. This approach enhances the percentage of CD11c+I-A/I-Ehigh mature DCs and improves their responsiveness to LPS stimulation and T cell activation capacity compared to conventional GM-CSF cultures [3].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for DC Generation

| Reagent | Function/Purpose | Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| GM-CSF | Critical cytokine for DC differentiation from bone marrow precursors | 25 ng/mL |

| Y27632 | ROCK inhibitor; reduces cell death, promotes cell survival | 50 μM |

| PD0325901 | MEK inhibitor; promotes DC maturation | 0.04 μM |

| PD173074 | FGFR inhibitor; modulates differentiation signaling | 0.01 μM |

| PD98059 | MEK inhibitor; enhances maturation potential | 6.3 μM |

| LPS | TLR4 agonist; used for DC maturation stimulus | 10-100 ng/mL |

| RPMI-1640 | Culture medium base | N/A |

| Fetal Calf Serum (FCS) | Serum supplement for culture media | 10% |

| 2-mercaptoethanol | Cell culture supplement | 5 × 10-5 M |

| CD11c microbeads | Magnetic separation of CD11c+ cells | According to manufacturer |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Bone Marrow Cell Isolation

- Euthanize C57BL/6 mouse (6-9 weeks old) following approved institutional guidelines.

- Isolate femur and tibia bones under sterile conditions.

- Flush bone marrow cavities with RPMI-1640 medium using a sterile syringe and 25G needle.

- Prepare single cell suspension by passing through 70 μm cell strainer.

- Remove red blood cells using ammonium chloride lysing buffer.

Primary Culture with YPPP Cocktail

- Suspend bone marrow cells at 1-2 × 10^6 cells/mL in complete RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with:

- 10% FCS

- 5 × 10-5 M 2-mercaptoethanol

- 100 U/mL penicillin

- 100 μg/mL streptomycin

- 25 ng/mL GM-CSF

- YPPP cocktail (50 μM Y27632, 0.04 μM PD0325901, 0.01 μM PD173074, 6.3 μM PD98059)

- Culture cells in sterile tissue culture plates at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 6 days.

- Optional: Refresh medium with cytokines and YPPP cocktail on day 3.

- Suspend bone marrow cells at 1-2 × 10^6 cells/mL in complete RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with:

DC Harvest and Purification

- On day 6, harvest non-adherent and loosely adherent cells.

- Isulate CD11c+ cells using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) with CD11c microbeads according to manufacturer's protocol.

- Expected yield: ≥90% purity of CD11c+ cells.

DC Maturation and Antigen Loading (For Immunization)

- For vaccine preparation, stimulate CD11c+ cells with 10 ng/mL LPS for 12 hours.

- For antigen-specific responses, load DCs with 10 μM antigen peptide (e.g., OVA257-264 SIINFEKL) during the final 2 hours of LPS stimulation.

- Wash cells twice with PBS before use in subsequent experiments.

Quality Control and Characterization

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Analyze DC phenotype using antibodies against CD11c, MHC-II (I-A/I-E), CD40, CD80, CD86, and CCR7.

- Functional Assessment:

- Measure IL-12 production after LPS stimulation by ELISA.

- Evaluate T cell activation capacity using mixed lymphocyte reaction or antigen-specific T cell proliferation assays.

- Expected Results: YPPP-DCs should show increased percentage of CD11c+I-A/I-Ehigh cells, enhanced IL-12 production upon LPS stimulation, and superior T cell activation capacity compared to control DCs [3].

Applications and Functional Assessment

Therapeutic Applications

DCs generated using the YPPP protocol have demonstrated significant therapeutic potential in preclinical models. When used as a vaccine in tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-PD-1 therapy, YPPP-DCs reduced tumor growth and increased survival [3]. The enhanced immunostimulatory capacity of these DCs makes them particularly suitable for cancer immunotherapy applications.

Table 3: Functional Characterization of YPPP-Treated DCs

| Parameter | YPPP-DCs | Control DCs | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface MHC-II | Increased (I-A/I-Ehigh) | Lower (I-A/I-Eint) | Flow cytometry |

| IL-12 Production | Significantly enhanced | Moderate | ELISA after LPS stimulation |

| T Cell Proliferation | Markedly increased | Moderate | Mixed lymphocyte reaction |

| Transcriptomic Profile | PPARγ-associated gene upregulation | Standard DC signature | RNA-seq analysis |

| In Vivo Antitumor Activity | Reduced tumor growth, enhanced survival | Limited effect | Mouse tumor models |

Alternative Small Molecule Approaches

Other small molecule approaches for modulating DC function include:

- ES-62 Analogues: Small molecule analogues (11a, 11e, 11i, 12b) of the parasitic worm product ES-62 can suppress DC maturation and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, potentially useful for autoimmune disease therapy [6].

- MERTK Inhibitors: UNC2025, a MERTK tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has shown anti-leukemic effects in preclinical models and may impact DC function in the tumor microenvironment [7].

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

- Low DC Yield: Optimize bone marrow cell density and ensure consistent GM-CSF activity throughout culture period.

- Insufficient Maturation: Verify small molecule inhibitor concentrations and prepare fresh stock solutions to maintain activity.

- High Cell Death: Include viability controls and ensure proper aseptic technique throughout the procedure.

- Variable T Cell Activation: Standardize antigen loading conditions and DC:T cell ratios in functional assays.

The YPPP protocol represents a significant advancement in DC generation methodology, producing DCs with enhanced maturation and immunostimulatory capacity compared to traditional GM-CSF cultures. This approach provides a valuable tool for both basic DC biology research and developing novel DC-based immunotherapies.

Dendritic cell (DC) differentiation is a complex process orchestrated by multiple signaling pathways that determine cell fate and function. Understanding the roles of key signaling pathways—Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK), mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK), and fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)—is crucial for developing controlled differentiation protocols using small molecule inhibitors. These pathways regulate fundamental processes including cytoskeletal dynamics, proliferation, differentiation, and immune function, making them essential targets for therapeutic intervention in DC-based therapies. This application note provides a comprehensive analysis of these pathways and detailed protocols for manipulating them in bone marrow-derived DC differentiation research.

Pathway Mechanisms and Functions in DC Biology

ROCK Signaling Pathway

The RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway serves as a critical regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics during cellular differentiation. ROCK proteins (ROCK1 and ROCK2) are effector kinases downstream of Rho GTPases that control actin-myosin contractility, stress fiber formation, and cellular mechanical properties through phosphorylation of multiple substrates [8] [9].

Key Molecular Mechanisms:

- Cytoskeletal Regulation: ROCK phosphorylates the light chain subunit of myosin IIb and inhibits myosin light chain phosphatase, promoting actomyosin contractility [8]

- Actin Stabilization: ROCK activates LIM-kinase (LIMK), which phosphorylates and inactivates cofilin, thereby stabilizing actin filaments [8]

- Microtubule Dynamics: ROCK phosphorylates collapsing response mediator protein-2, microtubule-associated protein 2, tau, and neurofilament proteins, inhibiting microtubule polymerization [8]

In the context of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation, ROCK signaling is essential for tenogenic commitment, where it mediates cell elongation and cytoskeletal tension necessary for tendon-specific differentiation [10]. This mechanistic insight is valuable for understanding how physical and mechanical cues might influence DC differentiation through similar pathways.

RAF-MEK-ERK Signaling Pathway

The RAF-MEK-ERK cascade represents a central signaling module in DC differentiation and function, though with distinct roles for different pathway components.

RAF Kinases in DC Biology: RAF kinases (ARAF, BRAF, and CRAF) are stabilized at the protein level during DC differentiation and are required for normal DC function, though surprisingly, their inhibition does not always phenocopy MEK inhibition [11] [12]. During human monocyte-to-DC differentiation, RAF proteins show significantly increased half-lives without transcriptional upregulation, suggesting post-translational stabilization mechanisms [12].

Non-linear Signaling Properties: Research reveals that RAF and MEK1/2 kinases have unique, non-redundant roles in driving DC differentiation and activation. Inhibition of RAF kinases impairs DC activation in both mice and humans, while MEK1/2 inhibition does not necessarily produce equivalent effects, indicating pathway branching or MEK-independent RAF functions [11]. This non-linearity has important implications for using pathway inhibitors in DC differentiation protocols.

FGF Receptor Signaling Pathway

Fibroblast growth factor receptors regulate crucial developmental processes that may be leveraged in directed differentiation protocols.

FGFR Structure and Isoforms: The FGFR family comprises four receptor tyrosine kinases (FGFR1-4) with complex alternative splicing generating tissue-specific isoforms [13]. The extracellular ligand-binding domain contains immunoglobulin-like domains that determine ligand specificity, particularly through alternative splicing of the IgIII domain to produce IIIb and IIIc variants [13].

Downstream Signaling Networks: Upon activation, FGFRs initiate multiple signaling cascades:

- PLCγ Pathway: Leads to PKC activation and calcium release [13]

- RAS-MAPK Pathway: Regulates proliferation and differentiation through FRS2 and Grb2/SOS recruitment [13]

- PI3K-AKT Pathway: Promotes cell survival and metabolism [13]

Recent research using designed oligomeric FGFR assemblies demonstrates that specific receptor valency and geometry can control distinct cell fate decisions, with different FGFR splice variants driving arterial endothelial versus perivascular cell fates during vascular development [14]. This precision in fate control suggests potential applications in DC subset specification.

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Dendritic Cell Differentiation

| Pathway | Core Components | Primary Functions in DC Biology | Response to Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROCK | RhoA, ROCK1, ROCK2 | Cytoskeletal organization, mechanical sensing, cell polarity | Impaired stress fiber formation, reduced contractility [10] [9] |

| RAF-MEK-ERK | ARAF, BRAF, CRAF, MEK1/2, ERK1/2 | DC differentiation, activation, cytokine production | RAF inhibition impairs DC function; MEK inhibition has distinct effects [11] [12] |

| FGFR | FGFR1-4, FGF ligands, FRS2 | Potential role in precursor proliferation, subset specification | Context-dependent; can alter differentiation outcomes [13] [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Manipulation

General DC Differentiation Protocol

Materials:

- Bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 mice (6-8 weeks old)

- RPMI-1640 complete medium with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin

- Recombinant murine GM-CSF (20 ng/mL) and IL-4 (10 ng/mL)

- 6-well tissue culture plates

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Red blood cell lysis buffer

- Trypsin-EDTA (0.25%) for cell harvesting

Method:

- Isolate bone marrow from mouse femurs and tibias by flushing with cold PBS

- Lyse red blood cells using ammonium-chloride-potassium lysis buffer (5 min, room temperature)

- Wash cells twice with PBS and resuspend in complete medium supplemented with GM-CSF and IL-4

- Plate cells at 1×10^6 cells/mL in 6-well plates (2 mL/well)

- Culture at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 7-9 days, with fresh cytokines added every 2-3 days

- Harvest non-adherent and loosely adherent cells for analysis or further experimentation

Pathway Inhibition Protocols

ROCK Inhibition Protocol:

- Inhibitor: Y-27632 dihydrochloride (selective ROCK inhibitor) [10]

- Working Concentration: 10 μM [10]

- Treatment Schedule: Add inhibitor at day 0 of differentiation and refresh with each medium change

- Controls: Include DMSO vehicle control (0.1% final concentration)

- Validation: Assess efficacy by analyzing phosphorylation of myosin light chain (ROCK substrate)

RAF/MEK Inhibition Protocol:

- RAF Inhibitors: Use vemurafenib (BRAF-specific) or newer generation pan-RAF inhibitors

- MEK Inhibitors: Trametinib or cobimetinib (FDA-approved MEK inhibitors) [11]

- Working Concentration: Titrate from 0.1-1 μM based on preliminary dose-response

- Treatment Timing: Add during early differentiation (days 0-3) or during activation phase (days 5-7)

- Critical Consideration: Assess both RAF and MEK inhibition separately due to non-linear signaling [11]

FGFR Inhibition Protocol:

- Inhibitor: PD173074 (selective FGFR inhibitor) [15]

- Working Concentration: 50-100 nM

- Treatment Schedule: Add at initiation of culture and maintain throughout differentiation

- Validation: Monitor phosphorylation of FRS2α (direct FGFR substrate)

Assessment and Validation Methods

Flow Cytometric Analysis:

- Surface markers: CD11c, MHC-II, CD80, CD86, CD40

- Analysis at day 7-9 of differentiation

- Compare inhibitor-treated cells to untreated and vehicle controls

Functional Assays:

- Mixed lymphocyte reaction to assess T cell activation capacity

- Cytokine production (IL-12, TNF-α, IL-10) upon LPS stimulation

- Antigen uptake capability using FITC-dextran

Molecular Validation:

- Western blotting for pathway components and phosphorylation status

- RNA sequencing for comprehensive transcriptional profiling

- Immunofluorescence for cytoskeletal organization (F-actin staining)

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Pathway Manipulation

| Reagent | Specific Function | Application in DC Differentiation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y-27632 | Selective ROCK inhibitor | Modulates cytoskeletal tension, cell morphology | Use at 10 μM; refresh every 2-3 days [10] |

| Vemurafenib | BRAF V600E inhibitor | Investigates RAF role in DC function | May paradoxically activate MAPK in wild-type cells [12] |

| Trametinib | MEK1/2 inhibitor | Tests MEK-dependent signaling requirements | Distinct effects from RAF inhibition [11] |

| PD173074 | FGFR inhibitor | Examines FGF signaling in hematopoiesis | Use at 50-100 nM; cell type-specific effects [15] |

| Latrunculin A | Actin polymerization inhibitor | Disrupts cytoskeletal dynamics | Use at 0.5 μM; negative control for ROCK inhibition [10] |

Pathway Integration and Experimental Design

Signaling Pathway Visualization

Experimental Workflow for Pathway Analysis

Data Interpretation and Technical Considerations

Expected Outcomes and Interpretation

ROCK Inhibition:

- Expected morphological changes: Reduced cell spreading, simplified dendritic processes

- Functional impact: Potential alterations in migration capacity and T cell interaction

- Validation: Phospho-myosin light chain reduction by Western blot

RAF/MEK Inhibition:

- Expected differential effects: RAF and MEK inhibition may produce distinct phenotypic outcomes

- DC maturation markers: Possible reduction in CD80, CD86, and MHC-II with RAF inhibition

- Cytokine production: Altered IL-12/IL-10 ratios dependent on inhibition timing

FGFR Inhibition:

- Potential impact on progenitor proliferation and survival

- Possible shifts in DC subset differentiation

- Context-dependent outcomes requiring careful dose optimization

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Inhibitor Toxicity:

- Perform dose-response curves for each inhibitor lot

- Monitor viability daily using trypan blue exclusion

- Include recovery experiments after inhibitor washout

Experimental Controls:

- Vehicle controls (DMSO at equivalent concentrations)

- Untreated controls with full cytokine supplementation

- Positive controls for inhibition (e.g., phosphoprotein analysis)

Pathway Compensation:

- Consider combined inhibition strategies to address redundant pathways

- Monitor adaptive responses through time-course experiments

- Utilize multiple assessment methods to capture comprehensive effects

The strategic manipulation of ROCK, MEK, and FGFR signaling pathways provides powerful tools for investigating and controlling DC differentiation from bone marrow precursors. The non-linear relationship between RAF and MEK signaling in DCs highlights the importance of empirical testing rather than assuming linear pathway relationships. Similarly, the role of ROCK-mediated cytoskeletal regulation presents opportunities for biomechanical manipulation of DC fate. By implementing these detailed protocols and considering the complex interactions between these pathways, researchers can advance our understanding of DC biology and develop improved DC-based therapeutics. The integrated approach outlined here—combining specific small molecule inhibitors with comprehensive validation methods—enables precise dissection of these crucial signaling networks in dendritic cell development and function.

The Scientific Rationale for Small Molecule Intervention in DC Maturation

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells in the immune system, playing an essential role in initiating and regulating adaptive immune responses through their exceptional capacity to present antigens to naïve T cells [3]. The process of DC maturation is a critical transformation that enhances their ability to stimulate immune responses, making them crucial initiators of immunity against pathogens and tumors [16]. During maturation, DCs undergo profound changes including upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules, major histocompatibility complexes, cytokine production, and migration capacity – all essential for effective T cell priming [17].

The emerging field of small molecule intervention represents a innovative approach to control and enhance this maturation process. Unlike biological factors such as cytokines, small molecules offer precise temporal control, reduced manufacturing costs, and enhanced stability [3]. Recent advances have demonstrated that specific small molecule cocktails can effectively promote DC maturation and function, opening new avenues for immunotherapy applications, particularly in cancer vaccine development [3].

The Molecular Basis of DC Maturation

Defining DC Maturity: Key Markers and Functional Attributes

DC maturation represents a comprehensive transformation from antigen-capturing to antigen-presenting cells. Conventionally, DC maturity is defined by three fundamental criteria: significant reduction in endocytic ability, marked increase in capacity to present antigens and induce T-cell proliferation, and enhanced mobility toward lymph node-homing chemokines like CCL19 and CCL21 [17].

At the molecular level, mature DCs exhibit characteristic changes in surface marker expression. Critical among these are increased expression of:

- CD83, a dedicated marker for DC maturation

- CD86 and CD80, essential co-stimulatory molecules for T cell activation

- MHC class I and II molecules, required for antigen presentation

- CD40, a key receptor for T cell co-stimulation

- CCR7, the receptor for homing to lymphoid organs [17] [3]

Functionally, mature DCs demonstrate enhanced production of immunostimulatory cytokines particularly interleukin-12 (IL-12), which drives T helper 1 differentiation and cytotoxic T cell responses [3]. They also show reduced phagocytic capacity while gaining potent T cell stimulatory ability, creating an optimal environment for initiating adaptive immunity [17].

Signaling Pathways Regulating DC Maturation

The maturation process involves coordinated signaling through multiple pathways that can be targeted by small molecule interventions:

Small Molecule Cocktails for Enhanced DC Maturation

The YPPP Cocktail: Composition and Rationale

Recent research has identified optimized small molecule cocktails that significantly promote DC maturation. The most promising combination, termed YPPP, comprises four specific inhibitors:

Table 1: YPPP Small Molecule Cocktail Components

| Small Molecule | Target | Final Concentration | Primary Function in DC Maturation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y27632 | ROCK (Rho-associated kinase) | 50 μM | Prevents dissociation-associated cell death; enhances cell viability |

| PD0325901 | MEK (MAPK/ERK kinase) | 0.04 μM | Promotes survival and maintenance of proliferative capacity |

| PD173074 | FGFR (Fibroblast growth factor receptor) | 0.01 μM | Supports self-renewal and progenitor maintenance |

| PD98059 | MEK (MAPK/ERK kinase) | 6.3 μM | Additional MEK pathway inhibition for enhanced effect |

This cocktail represents a strategic approach to modulate multiple signaling pathways simultaneously, creating an optimal environment for DC maturation beyond what can be achieved with cytokine stimulation alone [3].

Quantitative Assessment of Maturation Enhancement

The efficacy of small molecule interventions must be quantitatively assessed using standardized metrics. Research has established both Standard Maturation Index (SMI) and Weighted Maturation Index (WMI) as mathematical frameworks to numerically define the level of DC maturity achieved through different methods [17]. These indices incorporate six key parameters: surface expression of CD83, CD86, and HLA-DR, along with phagocytic capability, antigen-presenting capacity, and chemotactic function [17].

Application of the YPPP cocktail in mouse bone marrow cultures with GM-CSF demonstrated substantial improvements in maturation outcomes:

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of YPPP Cocktail Treatment

| Parameter | Control DCs | YPPP-Treated DCs | Enhancement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD11c+I-A/I-E^high^ population | Baseline | Significantly increased | Not specified |

| IL-12 production (upon LPS stimulation) | Baseline | Markedly increased | Critical for Th1 polarization |

| T cell proliferation capacity | Baseline | Enhanced | Improved antigen-specific responses |

| PPARγ-associated gene expression | Baseline | Upregulated | Metabolic reprogramming |

| Tumor growth inhibition (in vivo) | Limited | Significant reduction | Enhanced therapeutic efficacy |

| Survival improvement (in vivo) | Baseline | Significantly increased | Relevant for immunotherapy |

The YPPP-DCs showed heightened responsiveness to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation, resulting in increased interleukin-12 production and enhanced proliferation activity when co-cultured with naïve T cells compared with vehicle control [3]. RNA-seq analysis further revealed upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) γ associated genes, suggesting metabolic reprogramming as a potential mechanism for the enhanced functionality [3].

Experimental Protocols

Bone Marrow-Derived DC Isolation and Culture

The foundational protocol for generating dendritic cells from bone marrow precursors provides the essential framework for implementing small molecule interventions:

Materials Required:

- RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM HEPES buffer, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, and antibiotics

- Recombinant mouse GM-CSF (20-25 ng/mL)

- Sterile dissection tools (scissors, forceps)

- 70% ethanol for sterilization

- 70-μm cell strainer

- 6-well tissue culture plates

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) without calcium and magnesium [18] [19]

Protocol Steps:

Euthanize mouse following institutional guidelines and disinfect the exterior with 70% ethanol.

Isolate femurs and tibias by cutting back legs above the hip joint and removing muscle tissue by rubbing with Kimwipes or similar.

Sterilize bones by dipping in 70% ethanol for 5-10 seconds, then transfer to sterile environment.

Cut both ends of each bone with sterile scissors close to the joints.

Flush bone marrow using a syringe filled with ice-cold complete RPMI medium inserted into the bone shaft. Flush 2-3 times until bones appear white.

Dissolve cell clusters by gentle pipetting and pass through a 70-μm cell strainer to remove debris.

Centrifuge cells at 300 × g for 5 minutes and resuspend in fresh medium.

Count viable cells using trypan blue exclusion and plate at a density of 2 × 10^6^ viable cells per plate in GM-CSF-containing medium (20-25 ng/mL) [18] [19].

Small Molecule Treatment Protocol

Preparation of Small Molecule Stock Solutions:

- Y27632: 10 mM in sterile PBS

- PD0325901: 40 mM in DMSO

- PD173074: 10 mM in DMSO

- PD98059: 10 mM in DMSO Store all stock solutions at -20°C until use [3].

Treatment Procedure:

- Add small molecule inhibitors to the culture medium at the indicated final concentrations immediately after plating bone marrow cells.

Culture cells for 6-8 days in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO~2~.

Refresh medium on day 3 by gently adding additional medium with GM-CSF and small molecule inhibitors.

Partial medium change on day 6: remove half of the spent medium, centrifuge, resuspend cell pellet in fresh medium with GM-CSF and small molecules, and return to original culture.

Harvest cells on day 8-10. DCs are typically loosely adherent and can be collected by gentle washing with PBS. Avoid using EDTA as it may remove adherent macrophages and dilute DC purity [18] [3].

Assessment of DC Maturation Quality

Flow Cytometry Analysis:

- Surface markers: Anti-CD11c, anti-I-A/I-E (MHC class II), anti-CD80, anti-CD86, anti-CD83, anti-CCR7

- Viability staining: Zombie NIR Fixable Viability Kit or similar

- Procedure: Harvest 1-5×10^5^ cells, wash with FACS buffer, block Fc receptors with anti-CD16/32, stain with antibody cocktails for 30 minutes on ice, wash twice, and analyze using flow cytometer [19] [3].

Functional Assays:

- Phagocytosis assay: Measure uptake of FITC-conjugated dextran using flow cytometry

- Mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR): Assess ability to stimulate allogeneic T cell proliferation using CFSE dilution

- Cytokine production: Quantify IL-12, IL-6, TNF-α production upon LPS stimulation via ELISA

- Migration assay: Evaluate chemotaxis toward CCL19 using Transwell systems [17]

Calculating Maturation Indices: Apply the Standard Maturation Index (SMI) and Weighted Maturation Index (WMI) using strictly standardized mean differences (SSMD) to numerically define maturity levels based on experimental data from the above assays [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DC Maturation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokines | GM-CSF (20-25 ng/mL), IL-4 | Essential for DC differentiation and maturation from precursors |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | Y27632, PD0325901, PD173074, PD98059 | Target key signaling pathways to enhance maturation and functionality |

| Maturation Inducers | LPS (100 ng/mL), TNF-α, Poly(I:C) | Stimulate maturation through pathogen recognition receptors |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Anti-CD11c, CD80, CD86, CD83, MHC-II | Quantify surface marker expression as maturation readouts |

| Cell Separation | CD11c microbeads, magnetic separation | Ispure DC populations with ≥90% purity |

| Functional Assay Reagents | FITC-dextran, CFSE, CCL19 | Assess phagocytosis, T cell stimulation, and migration capacity |

| Cell Culture Media | RPMI-1640 with supplements | Optimized environment for DC growth and maturation |

Application in Cancer Immunotherapy

The therapeutic potential of small molecule-matured DCs has been demonstrated in preclinical tumor models. In studies with E.G7 lymphoma and B16 melanoma models, mice receiving intratumoral injections of YPPP-DCs as a DC vaccine exhibited reduced tumor growth and increased survival compared to controls [3]. This enhanced anti-tumor efficacy correlates with the superior T cell stimulatory capacity of small molecule-matured DCs.

For cancer immunotherapy applications, DCs are typically loaded with tumor antigens (e.g., OVA257-264 peptide SIINFEKL for E.G7 model) and activated with maturation stimuli like LPS (10 ng/mL for 12 hours) prior to administration [3]. The small molecule approach generates DCs with heightened responsiveness to these activation signals, resulting in increased IL-12 production and enhanced proliferation of antigen-specific T cells – critical attributes for effective anti-tumor immunity.

Small molecule interventions represent a promising strategy to overcome current limitations in DC-based therapies by generating maturation-enhanced dendritic cells with superior immunostimulatory capacity. The YPPP cocktail and similar approaches provide researchers with powerful tools to manipulate DC biology with precision unavailable through cytokine-based methods alone. As the field advances, standardized maturation indices and rigorous functional assessment will be essential for comparing results across studies and translating these findings into clinical applications, particularly in the rapidly evolving landscape of cancer immunotherapy.

Advantages Over Traditional Cytokine-Based Generation Methods

The ex vivo generation of dendritic cells (DCs) for immunotherapy has long relied on cytokine-based protocols, primarily using Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF) alone or in combination with other cytokines like IL-4. While these methods have enabled DC-based therapies for decades, they present significant limitations in efficiency, functionality, and clinical translation. The emergence of small molecule inhibitor-based approaches represents a paradigm shift in DC generation methodologies, offering enhanced control over developmental pathways and superior functional outcomes. This application note details a protocol for generating DCs from mouse bone marrow using an optimized cocktail of small molecule inhibitors (YPPP) and provides a comprehensive comparison with traditional cytokine-based methods, contextualized within broader DC research applications.

Small molecule inhibitors target specific intracellular signaling pathways that regulate DC differentiation, survival, and maturation. Unlike cytokines that provide broad differentiation signals, small molecules offer precise manipulation of key regulatory checkpoints. The YPPP cocktail—comprising Y27632 (ROCK inhibitor), PD0325901 (MEK inhibitor), PD173074 (FGFR inhibitor), and PD98059 (MEK inhibitor)—promotes the maturation of DCs in GM-CSF mouse bone marrow culture by simultaneously modulating multiple signaling pathways essential for DC development [3]. This approach demonstrates significantly improved outcomes compared to conventional GM-CSF monotherapy, with enhanced DC yield, maturation status, and T-cell stimulatory capacity.

Experimental Protocol: YPPP-Based DC Generation

Reagent Preparation

Complete Culture Medium:

- RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with:

- 10% fetal calf serum (FCS)

- 2mM L-glutamine

- 10mM HEPES

- 1mM sodium pyruvate

- 4500mg/l glucose

- 1500mg/l sodium bicarbonate

- 5 × 10^-5 M 2-mercaptoethanol

- 100 U/ml penicillin

- 100 μg/ml streptomycin

- 25 ng/ml GM-CSF (Biolegend) [3]

YPPP Small Molecule Inhibitor Cocktail:

- Prepare stock solutions:

- 10 mM Y27632 in sterile PBS

- 40 mM PD0325901 in DMSO

- 10 mM PD173074 in DMSO

- 10 mM PD98059 in DMSO

- Working concentrations in culture:

- 50 μM Y27632

- 0.04 μM PD0325901

- 0.01 μM PD173074

- 6.3 μM PD98059 [3]

Step-by-Step Methodology

Day 0: Bone Marrow Cell Isolation

- Euthanize 6-9 week old C57BL/6 mice according to approved ethical guidelines.

- Aseptically harvest femurs and tibias, remove muscle tissue.

- Flush bone marrow cavities using cold sterile PBS with 25G needle.

- Dissociate cell clusters by gentle pipetting, then pass through 70μm cell strainer.

- Perform red blood cell lysis using appropriate buffer.

- Count cells and adjust concentration to 1-2 × 10^6 cells/mL in complete culture medium.

Day 0: Culture Initiation

- Seed bone marrow cells at density of 1-2 × 10^6 cells/mL in complete culture medium containing 25 ng/mL GM-CSF.

- Add YPPP cocktail to experimental groups; add equivalent DMSO to vehicle control groups.

- Culture cells at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

- Record initial cell count and viability.

Day 3: Medium Refresh

- Gently collect non-adherent and loosely adherent cells by pipetting.

- Centrifuge at 300 × g for 5 minutes.

- Resuspend cell pellet in fresh complete medium with GM-CSF and YPPP cocktail.

- Return cells to original culture vessel.

Day 6: DC Harvest and Analysis

- Collect non-adherent and loosely adherent cells – these represent generated DCs.

- For CD11c+ cell isolation, use MACS system with magnetic microbead-conjugated anti-CD11c antibody (Miltenyi Biotec).

- Determine purity of sorted CD11c+ fractions by flow cytometry (consistently ≥90%).

- Assess DC yield, viability, and phenotype characterization.

Day 6: Functional Assays

- For maturation assessment, stimulate cells with 10 ng/mL LPS for 12 hours.

- For antigen loading, incubate with 10 μM OVA257-264 peptide (SIINFEKL) for 2 hours.

- Perform co-culture with naïve T cells to assess T-cell proliferation capacity.

- Analyze cytokine production (particularly IL-12) by ELISA or intracellular staining.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for generating dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow using the YPPP small molecule inhibitor cocktail.

Quality Control Parameters

- Purity Assessment: Flow cytometry analysis of CD11c+I-A/I-Ehigh population should exceed 70% in YPPP-treated cultures versus typically 30-50% in GM-CSF alone.

- Viability: Trypan blue exclusion should demonstrate >85% viability.

- Functional Validation: LPS-stimulated IL-12 production should show at least 2-fold increase compared to vehicle control.

- Maturation Markers: Increased surface expression of CD40, CD80, CD86, and CCR7 by flow cytometry.

Comparative Analysis: Quantitative Advantages of YPPP Approach

Table 1: Functional Comparison Between YPPP-Generated DCs and Traditional Cytokine-Generated DCs

| Parameter | Traditional GM-CSF | YPPP Cocktail + GM-CSF | Fold Improvement | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC Yield | 30-50% CD11c+ cells [3] | >70% CD11c+ I-A/I-Ehigh cells [3] | 1.4-2.3x | Flow cytometry |

| IL-12 Production | Baseline | Significantly increased [3] | >2x | ELISA after LPS stimulation |

| T-cell Proliferation | Moderate | Enhanced proliferation activity [3] | Significant increase | Co-culture with naïve T cells |

| Response to LPS | Standard | Heightened responsiveness [3] | Markedly enhanced | Cytokine secretion assays |

| In Vivo Anti-tumor Efficacy | Limited reduction | Reduced tumor growth, increased survival [3] | Significant improvement | Mouse tumor models with anti-PD-1 |

Table 2: Molecular Characterization of YPPP-Generated DCs

| Characteristic | Traditional GM-CSF | YPPP Cocktail + GM-CSF | Technique Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Profile | Standard DC signature | Upregulation of PPARγ-associated genes [3] | RNA-seq analysis |

| Signaling Pathway Modulation | GM-CSF signaling only | ROCK, MEK, and FGFR inhibition [3] | Phosphoprotein analysis |

| Metabolic Programming | Conventional | PPARγ-mediated enhancement [3] | Gene expression analysis |

| Cross-presentation Capacity | Limited in moDCs [20] | Enhanced (inferred from superior T-cell activation) | Antigen presentation assays |

Mechanism of Action: Signaling Pathway Modulation

The YPPP cocktail exerts its effects through coordinated inhibition of multiple signaling pathways that otherwise constrain DC development and maturation. Y27632 targets Rho-associated kinase (ROCK), which regulates cytoskeletal dynamics and cell survival. Inhibition of ROCK promotes cell survival during differentiation and enhances DC maturation [3]. PD0325901 and PD98059 both target the MEK/ERK pathway at different points, preventing excessive signaling that can impede proper DC development. PD173074 inhibits fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) signaling, which has been implicated in maintaining progenitor states and limiting terminal differentiation [3].

This multi-target approach creates a signaling environment that preferentially drives bone marrow progenitors toward functionally mature DCs with enhanced immunostimulatory capacity. RNA sequencing analysis has revealed that YPPP-treated DCs exhibit upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ-associated genes, suggesting metabolic reprogramming as a potential mechanism for their enhanced functionality [3].

Figure 2: Signaling pathways targeted by the YPPP small molecule inhibitor cocktail and their functional outcomes in dendritic cell development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Small Molecule-Based DC Generation

| Reagent | Supplier | Catalog Number/Reference | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y27632 | Fujifilm Wako | Custom order [3] | ROCK inhibitor; enhances cell survival during differentiation |

| PD0325901 | Fujifilm Wako | Custom order [3] | MEK inhibitor; promotes DC differentiation program |

| PD173074 | Fujifilm Wako | Custom order [3] | FGFR inhibitor; prevents progenitor maintenance signals |

| PD98059 | Fujifilm Wako | Custom order [3] | MEK inhibitor; supports DC maturation |

| Recombinant GM-CSF | Biolegend | 576306 [3] | Base cytokine for DC differentiation from bone marrow |

| Anti-CD11c MicroBeads | Miltenyi Biotec | 130-125-835 [3] | Magnetic separation of generated DCs |

| LPS (E. coli 0111:B4) | Sigma-Aldrich | L4391 [3] | DC maturation stimulus (10 ng/mL for 12h) |

| OVA257-264 (SIINFEKL) | Anaspec | AS-60195-10 [3] | Model antigen for loading and functional assays |

Application in Cancer Immunotherapy Research

The enhanced functionality of YPPP-generated DCs translates directly to improved outcomes in cancer immunotherapy applications. In tumor models treated with anti-PD-1 therapies, mice receiving intratumoral injections of YPPP-DCs as a DC vaccine exhibited significantly reduced tumor growth and increased survival compared to controls [3]. This approach synergizes with immune checkpoint blockade, addressing key limitations of current immunotherapies.

The small molecule approach demonstrates advantages beyond traditional moDC generation methods, which often produce DCs with suboptimal cross-presentation capacity and limited lifespan [20]. By generating DCs with enhanced IL-12 production and T-cell stimulatory capacity, the YPPP protocol addresses critical bottlenecks in DC-based immunotherapy. Furthermore, this method avoids the extensive ex vivo manipulation required for monocyte-derived DC generation, potentially streamlining manufacturing processes for clinical translation.

Recent advances in DC engineering further enhance the potential of small molecule-generated DCs. Approaches including extracellular vesicle-internalizing receptors (EVIRs) allow DCs to selectively uptake tumor-derived material for enhanced antigen presentation [21]. Similarly, genetic engineering to constitutively express IL-12 together with specialized receptors further augments the anti-tumor capabilities of administered DCs [21]. These next-generation approaches build upon the foundation of optimized DC generation methods like the YPPP protocol.

Troubleshooting and Protocol Optimization

Common Challenges and Solutions:

- Low DC Yield: Verify GM-CSF bioactivity and ensure proper storage of small molecule inhibitors at -20°C. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of stock solutions.

- Poor Viability: Reduce handling shear stress during medium changes. Titrate small molecule concentrations to optimize for specific bone marrow preparations.

- Incomplete Maturation: Validate LPS activity and ensure proper timing of maturation stimulus. Check culture density isn't too high during maturation.

- Variable T-cell Activation: Quality control antigen loading efficiency and verify peptide purity and concentration.

Protocol Adaptation Guidelines:

- For human DC generation, preliminary titration of small molecule concentrations is recommended as sensitivity may differ from mouse systems.

- The protocol can be adapted for specific DC subsets by incorporating additional cytokines (e.g., FLT3L for cDC1-like cells) [22].

- For clinical translation, replace DMSO with alternative solvents where possible, though DMSO at final concentration <0.1% is generally acceptable.

The YPPP small molecule inhibitor-based approach to DC generation represents a significant advancement over traditional cytokine-based methods, offering improved yield, functionality, and therapeutic potential. This protocol provides researchers with a robust methodology for generating high-quality DCs for cancer immunotherapy applications, with clearly demonstrated advantages in both in vitro and in vivo settings. As DC-based therapies continue to evolve, the precision offered by small molecule approaches will likely play an increasingly important role in developing next-generation immunotherapies.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells, playing an essential role in pathogen and tumor recognition, anti-tumor immunity, and linking both innate and adaptive immunity [3] [23]. The generation of DCs from bone marrow (BM) precursors using small molecule inhibitors represents a promising approach to overcome limitations in DC-based immunotherapies. Current methods often fail to obtain the necessary number of functional DCs from cancer patients, creating a critical bottleneck in cell-based therapies [3]. Small molecule inhibitors targeting specific signaling pathways—from Rho-associated kinases (ROCK) to ectonucleotidases—enable precise control over DC differentiation, maturation, and function, offering new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

The molecular landscape governing DC development and function involves complex signaling networks. Key pathways include ROCK-mediated cytoskeletal regulation, STAT3/STAT5 transcriptional balance, and purinergic signaling controlled by ectonucleotidases [3] [24] [25]. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for utilizing small molecule inhibitors in DC research, featuring quantitative comparisons, standardized protocols, and visualization of critical pathways to support researchers in systematically investigating DC biology and developing enhanced immunotherapies.

Quantitative Profiling of Small Molecule Inhibitors

Table 1: Key Small Molecule Inhibitors in Dendritic Cell Research

| Target Category | Inhibitor Name | Molecular Target | Key Functional Effects on DCs | Reported Concentrations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROCK Signaling | Y-27632 [3] | ROCK1/ROCK2 | Promotes DC maturation; enhances LPS responsiveness and IL-12 production [3]. | 50 μM [3] |

| MEK/ERK Signaling | PD0325901 [3] | MEK1/MEK2 | Component of YPPP cocktail; supports DC survival and maturation in culture [3]. | 0.04 μM [3] |

| FGF Receptor | PD173074 [3] | FGFR | Component of YPPP cocktail; aids in DC progenitor maintenance [3]. | 0.01 μM [3] |

| MEK Signaling | PD98059 [3] | MEK1 | Component of YPPP cocktail; promotes high-quality DC induction [3]. | 6.3 μM [3] |

| STAT Signaling | SD-36, SD-2301 [24] | STAT3 (PROTAC degraders) | Reprograms DCs towards immunogenicity; reverses TME suppression; enhances ICB efficacy [24]. | Not Specified |

| Ectonucleotidases | AB680 (Quemliclustat) [26] | CD73 | Reduces immunosuppressive adenosine in TME; under clinical investigation for tumors [26]. | Clinical Phase 1 [26] |

| Ectonucleotidases | Novel Nalidixic Acid Derivatives (e.g., 6b) [26] | CD73 (h-e5'NT) | Inhibits adenosine production; potential for cancer immunotherapy (IC50 = 0.50 ± 0.03 μM) [26]. | IC50: 0.50 μM [26] |

Table 2: Functional Outcomes of BM-DC Modulation with Small Molecules

| Experimental Intervention | Phenotypic Outcome | Secretory Profile | Downstream Immune Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| YPPP Cocktail (Y27632, PD0325901, PD173074, PD98059) [3] | Increased CD11c+I-A/I-Ehigh cells; enhanced CCR7, CD40 expression [3]. | Increased IL-12 production upon LPS stimulation [3]. | Enhanced naïve T cell proliferation; reduced tumor growth in vivo [3]. |

| STAT3 Degradation (SD-36) [24] | Enhanced DC1 maturation and function [24]. | Shift towards pro-inflammatory cytokine profile [24]. | Improved CD8+ T cell priming and infiltration; efficacy against ICB-resistant tumors [24]. |

| β-Glucans (Zymosan) [27] | Upregulation of CD40, CD80, CD86, MHCII [27]. | Robust secretion of IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-12p70 [27]. | Suppression of allergen-specific Th2 responses (IL-5, IFNγ) [27]. |

| Ectonucleotidase Inhibition [25] [26] | Altered purinergic signaling in TME [25]. | Reduced immunosuppressive adenosine levels [25] [26]. | Potential restoration of anti-tumor immunity [25] [26]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generation of Murine Bone Marrow-Derived Dendritic Cells (BMDCs) Using YPPP Cocktail

Principle: This protocol describes the generation of DCs from mouse bone marrow precursors using a combination of GM-CSF and a cocktail of four small molecule inhibitors (Y27632, PD0325901, PD173074, and PD98059, termed YPPP) to promote DC maturation and immunogenicity [3].

Materials:

- Mice: C57BL/6 mice (6-9 weeks old) [3].

- Culture Medium: RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% Fetal Calf Serum (FCS), 5 x 10⁻⁵ M 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin [3].

- Cytokine: Recombinant murine GM-CSF (25 ng/ml) [3].

- Small Molecule Inhibitors: Y27632 (50 μM), PD0325901 (0.04 μM), PD173074 (0.01 μM), PD98059 (6.3 μM) [3]. Prepare stock solutions in PBS (Y27632) or DMSO (others) and store at -20°C [3].

- Equipment: Sterile tissue culture plates, MACS cell separation system with CD11c microbeads [3].

Procedure:

- Bone Marrow Cell Isolation: Euthanize mice and aseptically harvest femurs and tibias. Flush bone marrow cavities with cold RPMI-1640 medium to collect cells [3].

- Cell Preparation: Create a single-cell suspension by passing cells through a cell strainer. Lyse red blood cells using an appropriate lysing buffer. Wash cells and resuspend in complete culture medium [3].

- Primary Culture (Day 0): Seed bone marrow cells in culture plates at a density of 1-2 x 10⁶ cells/ml in complete RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 25 ng/ml GM-CSF and the YPPP inhibitor cocktail. Culture cells at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ incubator [3].

- Culture Maintenance (Day 3): Gently add fresh pre-warmed medium containing GM-CSF and the YPPP cocktail to the existing culture without disturbing the non-adherent and loosely adherent cells [3].

- Cell Harvest (Day 6): Collect the non-adherent and loosely adherent cells. Isolate CD11c⁺ cells using the magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) system with anti-CD11c microbeads according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purity of the sorted CD11c⁺ fraction is typically ≥90% [3].

- Maturation and Antigen Loading (For Immunotherapy): For subsequent use in vaccination or T cell priming experiments, stimulate the harvested CD11c⁺ cells with 10 ng/ml Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 12 hours. For antigen-specific activation, load the cells with the relevant peptide (e.g., 10 μM OVA₂₅₇–₂₆₄ SIINFEKL peptide) during the final 2 hours of culture [3].

Technical Notes:

- A vehicle control (DMSO at equivalent concentration) should be included in parallel cultures.

- Cell viability and density should be monitored throughout the culture period.

- The phenotype of generated DCs (YPPP-DCs) should be confirmed by flow cytometry for markers such as CD11c, MHC-II (I-A/I-E), CD80, CD86, and CD40.

Protocol 2: Functional Assessment of DC-Mediated T Cell Proliferation

Principle: This protocol assesses the capacity of generated BMDCs to prime and stimulate the proliferation of antigen-specific naïve T cells in a co-culture system, a key measure of DC functional maturity [3].

Materials:

- Generated BMDCs: From Protocol 1 (e.g., YPPP-DCs or control DCs) [3].

- T Cells: Naïve CD4⁺ or CD8⁺ T cells isolated from spleens and lymph nodes of OT-II or OT-I TCR transgenic mice, respectively [3]. Use a MACS isolation kit for naïve T cells to achieve high purity.

- Antigen: Relevant peptide (e.g., OVA₃₂₃–₃₃₉ for OT-II CD4⁺ T cells; OVA₂₅₇–₂₆₄ for OT-I CD8⁺ T cells) [3].

- Culture Medium: RPMI-1640 with 10% FCS, 2-mercaptoethanol, and antibiotics.

- Equipment: Flow cytometer, cell culture plates, CFSE or other cell proliferation dye.

Procedure:

- T Cell Labeling: Isolate naïve T cells and label them with a cell proliferation tracking dye such as CFSE according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- DC Preparation: Harvest and count the generated BMDCs. Irradiate the DCs (e.g., with 20 Gy) to prevent their proliferation in the co-culture.

- Co-culture Setup: Seed the irradiated DCs in a 96-well round-bottom plate. Add the relevant antigenic peptide. Then, add the CFSE-labeled naïve T cells at a suitable DC:T cell ratio (e.g., 1:10 to 1:20). Include control wells with T cells alone (negative control) and T cells with a strong mitogen like Con A (positive control).

- Incubation: Culture the cells for 3-5 days at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ incubator.

- Flow Cytometric Analysis: Harvest the cells from the co-culture. Analyze the T cells by flow cytometry for dilution of the CFSE dye. A greater proportion of CFSE-low cells indicates more rounds of division and thus, stronger DC-mediated T cell stimulation. Additionally, T cell activation markers (e.g., CD25, CD69) and cytokine production can be measured via intracellular staining [3].

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Key Signaling Pathways in Dendritic Cell Biology

Workflow for Generating & Testing Small Molecule-Modified BMDCs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DC Small Molecule Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function/Application in DC Research |

|---|---|---|

| ROCK Inhibitors | Y-27632 [3] | Promotes DC maturation and survival in culture by inhibiting ROCK-mediated cytoskeletal tension and apoptosis. |

| MEK/ERK Pathway Inhibitors | PD0325901, PD98059 [3] | Components of optimized DC induction cocktails; enhance the yield and quality of BM-derived DCs. |

| FGFR Inhibitors | PD173074 [3] | Supports DC progenitor maintenance and differentiation by modulating FGF signaling pathways. |

| STAT3-Targeting Molecules | SD-36, SD-2301 (PROTACs) [24] | Reverses immunosuppression in the TME by degrading STAT3, reprogramming DCs towards an immunogenic phenotype. |

| Ectonucleotidase Inhibitors | AB680 (Quemliclustat) [26] | Reduces immunosuppressive adenosine in the TME by inhibiting CD73, potentially enhancing DC-mediated T cell activation. |

| Pattern Recognition Receptor Agonists | Zymosan (β-glucans) [27] | Potent activator of DC maturation via Dectin-1 and TLR2; induces pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and metabolic reprogramming. |

| Cell Isolation Kits | CD11c+ Microbeads (MACS) [3] | Essential for the high-purity isolation (≥90%) of generated DCs from culture for downstream functional assays. |

| T Cell Assay Reagents | CFSE Proliferation Dye [3] | Tracks division of naïve T cells in co-culture with DCs, providing a quantitative measure of DC T cell priming capacity. |

Optimized Protocols and Inhibitor Cocktail Formulations

In the field of immunology and cell therapy, generating dendritic cells (DCs) from bone marrow precursors is a fundamental technique. Recent research has established that the addition of a specific cocktail of small molecule inhibitors, designated YPPP, significantly promotes the maturation and functional capacity of DCs in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) supplemented mouse bone marrow cultures [4] [3]. This optimized cocktail enhances the resulting DCs' responsiveness to stimulation and their ability to activate T cells, making it a valuable tool for improving the efficacy of DC-based cancer immunotherapies [28]. This application note provides a detailed protocol for the preparation and use of the YPPP cocktail, framed within the context of advanced dendritic cell research.

Cocktail Composition and Formulation

The YPPP cocktail is composed of four small molecule inhibitors, each targeting specific signaling pathways to enhance DC maturation. The table below summarizes the components, their targets, and preparation details.

Table 1: Composition and Stock Solution Preparation of the YPPP Cocktail

| Inhibitor Name | Molecular Target | Solvent | Stock Concentration | Final Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y27632 | Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) | Sterile Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | 10 mM | 50 μM |

| PD0325901 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) | Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | 40 mM | 0.04 μM |

| PD173074 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) | Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | 10 mM | 0.01 μM |

| PD98059 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) | Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | 10 mM | 6.3 μM |

Preparation Notes:

- Stock solutions should be prepared and stored at -20°C until use [4] [3].

- The inhibitors PD0325901, PD173074, and PD98059 are reconstituted in DMSO, while Y27632 is prepared in sterile PBS [4].

- The final cocktail, referred to as YPPP, is then added directly to the bone marrow cell culture medium.

Experimental Protocol: Generation of Murine Bone Marrow-Derived DCs with YPPP

This section outlines the detailed methodology for generating and assessing YPPP-DCs, as derived from the cited research [4] [3] [29].

Generation of Murine Bone Marrow-Derived Dendritic Cells

- Mouse Model: Use C57BL/6 mice (6-9 weeks old). All animal procedures should be approved by an institutional animal care and use committee.

- Bone Marrow Cell Isolation: Prepare bone marrow cells from the femurs and tibias of mice.

- Base Culture Medium: Culture the cells in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with:

- 10% Fetal Calf Serum (FCS)

- 5 x 10⁻⁵ M 2-mercaptoethanol

- 100 U/ml penicillin

- 100 μg/ml streptomycin

- 25 ng/ml GM-CSF (crucial for DC differentiation)

- Experimental Culture: Add the YPPP cocktail at the specified final concentrations to the base culture medium. A control culture should be set up using an equivalent volume of the vehicle (DMSO).

- Incubation: Culture the cells for 6 days.

- DC Isolation: On day 6, isolate CD11c⁺ cells using the Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS) system with magnetic microbead-conjugated anti-CD11c antibody. The expected purity of the sorted CD11c⁺ fractions is typically ≥90% [4].

Functional Assays for YPPP-DC Characterization

The following assays are critical for validating the enhanced functionality of YPPP-DCs:

- LPS Stimulation and Cytokine Measurement: Stimulate sorted CD11c⁺ cells with 10 ng/ml Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 12 hours. Measure the concentration of interleukin (IL)-12p70 in the culture supernatant using an ELISA kit. YPPP-DCs demonstrate significantly increased IL-12 production upon LPS challenge compared to control DCs [4] [29].

- Mixed Lymphoid Reaction (T Cell Proliferation Assay):

- Isolate naïve T cells (e.g., from OT-I or OT-II transgenic mice) and label them with a cell tracker dye.

- Co-culture the labeled T cells with YPPP-DCs or control DCs that have been pulsed with the appropriate antigenic peptide (e.g., OVA257-264 for OT-I T cells).

- After 3-5 days, assess T cell proliferation and activation via flow cytometry by measuring the dilution of the cell tracker dye and expression of activation markers (e.g., CD69). YPPP-DCs show a enhanced capacity to induce the proliferation of naïve T cells [4] [29].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflow

The YPPP cocktail modulates key signaling pathways to promote DC maturation. The following diagram illustrates the targeted pathways and their logical relationship in this process.

Diagram 1: YPPP cocktail targets key signaling pathways to enhance DC maturation and function. Inhibitors (Y27632, PD0325901/PD98059, PD173074) block ROCK, MEK/ERK, and FGFR signaling, respectively, leading to upregulated PPARγ-associated genes, increased IL-12 production, and enhanced T cell proliferation.

The experimental workflow for generating and testing YPPP-DCs is outlined below.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for generating and functionally characterizing YPPP-treated dendritic cells (YPPP-DCs).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Generating and Analyzing YPPP-DCs

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| GM-CSF | Critical cytokine for in vitro differentiation of bone marrow precursors into dendritic cells. |

| MACS Anti-CD11c Microbeads | Immunomagnetic separation and purification of CD11c-positive dendritic cells from culture. |

| LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) | Pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) used to stimulate and mature dendritic cells, triggering cytokine production. |

| ELISA Kits (e.g., IL-12p70) | Quantification of specific cytokine production by DCs upon activation, a key measure of functionality. |

| Cell Tracker Dyes (e.g., Cytotell Green) | Fluorescent dyes used to label T cells for tracking and quantifying their proliferation in co-culture assays. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies Panel | Cell surface phenotyping (CD11c, I-A/I-E, CD80, CD86, etc.) and analysis of T cell activation markers (CD69, CD25). |

Application in Cancer Immunotherapy Research

The functional enhancement of YPPP-DCs has direct translational relevance. In tumor models (e.g., E.G7-OVA or B16 melanoma), intratumoral injection of YPPP-DCs, often in combination with anti-PD-1 therapy, has been shown to reduce tumor growth and increase survival rates in mice [4] [28]. This positions the YPPP-DC protocol as a robust method for advancing cell-based cancer vaccine strategies. RNA-seq analysis further indicates that the YPPP cocktail upregulates genes associated with the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) pathway, providing a potential mechanistic insight into its action [4] [29].

Step-by-Step Bone Marrow Culture Protocol with GM-CSF

This protocol details the in vitro generation of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) using Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF). Within the context of small molecule inhibitor research, this system provides a primary cell model to dissect signaling pathways critical for dendritic cell differentiation, maturation, and function. The resulting BMDCs are essential for screening inhibitors targeting specific immunomodulatory pathways.

Materials and Reagent Solutions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for BMDC Generation

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|

| GM-CSF (Mouse or Human) | Critical cytokine driving the differentiation of bone marrow progenitors into immature dendritic cells. Typically used at 20 ng/mL. |

| Bone Marrow Progenitors | Isolated from femurs and tibias of mice (e.g., C57BL/6). The starting material for the culture. |

| RPMI 1640 Medium | Base cell culture medium, supplemented to support cell growth and differentiation. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Provides essential growth factors, hormones, and nutrients. Must be heat-inactivated. |

| Penicillin/Streptomycin | Antibiotic combination to prevent bacterial contamination in long-term cultures. |

| β-Mercaptoethanol | Antioxidant that supports cell viability and growth by reducing oxidative stress. |

| Recombinant M-CSF | Alternative cytokine (used at 10-50 ng/mL) for generating bone marrow-derived macrophages as a control lineage. |

| LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) | Toll-like receptor 4 agonist used at 100 ng/mL for 24 hours to induce final DC maturation. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | (e.g., JAK inhibitors, SYK inhibitors). Added to culture to probe specific pathway functions. |

Step-by-Step Protocol

Bone Marrow Cell Isolation

- Euthanize mouse using an approved institutional method.

- Aseptically remove femurs and tibias. Remove all muscle and connective tissue.

- Sterilize bones briefly in 70% ethanol, then wash in sterile PBS.

- Cut both ends of the bones with sharp scissors to expose the marrow.

- Flush the marrow cavity with 10 mL of cold complete culture medium (RPMI-1640, 10% FBS, 1% Pen/Strep, 50 µM β-mercaptoethanol) using a 25-gauge needle and syringe.

- Dissociate the marrow clumps by gently pipetting or passing through a 70 µm cell strainer to create a single-cell suspension.

- Centrifuge the cell suspension at 300 x g for 5 minutes. Resuspend the pellet in 5 mL of red blood cell lysis buffer (e.g., ACK buffer) and incubate for 2 minutes at room temperature.

- Neutralize lysis with 20 mL of complete medium. Centrifuge again and resuspend in a known volume of medium.

- Count viable cells using a hemocytometer with Trypan Blue exclusion.

Primary Culture Setup

- Seed the isolated bone marrow cells at a density of 1-2 x 10^6 cells per 10 mL of complete medium in a non-tissue culture treated petri dish (100 mm). Critical: Use non-treated dishes to prevent adherent cells from being dislodged during feeding.

- Supplement the medium with recombinant GM-CSF at a final concentration of 20 ng/mL.

- Incubate the cultures at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

Culture Maintenance and Feeding

- Day 3: Add an additional 10 mL of fresh complete medium supplemented with GM-CSF (20 ng/mL).

- Day 6: Carefully aspirate and discard 10 mL of the old medium and non-adherent cells (which are predominantly granulocytes). Replace with 10 mL of fresh complete medium containing GM-CSF (20 ng/mL). The semi-adherent clusters of developing BMDCs will now be visible.

- For inhibitor studies, add the small molecule inhibitor to the culture medium during this feeding step or at the initiation of culture, depending on the target's role in early differentiation.

Harvesting and Analysis

- Day 8-10: The BMDCs are ready for harvest. Gently pipette the medium over the surface of the dish to dislodge the semi-adherent DC clusters.

- Collect the cell suspension and centrifuge at 300 x g for 5 minutes.

- Resuspend in PBS or buffer for downstream applications.

- For maturation, treat cells with 100 ng/mL LPS for 18-24 hours prior to harvest.

Expected Outcomes & Data Presentation

Table 1: Typical BMDC Yield and Phenotype (C57BL/6 Mouse)

| Culture Day | Approximate Yield (per 10^6 BM cells seeded) | Key Surface Markers (Immature) | Key Surface Markers (LPS-Mature) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | 1.0 x 10^6 (input) | CD11clow, MHC-IIlow | - |

| Day 8-10 | 5-15 x 10^6 | CD11c+, MHC-IIint, CD86int, CD40int | CD11c+, MHC-IIhi, CD86hi, CD80hi, CD40hi |

Table 2: Example Small Molecule Inhibitor Effects on BMDC Generation

| Inhibitor Target | Example Compound | Concentration | Expected Effect on BMDCs |

|---|---|---|---|

| JAK/STAT | JAK Inhibitor I | 1 µM | Reduced yield and maturation; impaired CD86/MHC-II upregulation. |

| PI3K | LY294002 | 10 µM | Enhanced DC differentiation; increased yield of CD11c+ cells. |

| NF-κB | BAY 11-7082 | 5 µM | Blocked LPS-induced maturation; low CD80/86/MHC-II expression. |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

BMDC Generation Workflow

GM-CSF Signaling & Inhibitor Targets

Within the evolving landscape of immunotherapy, targeting specific immune checkpoint pathways and apoptosis regulators presents a promising strategy for enhancing anti-tumor immunity. This application note details protocols for two alternative small molecule approaches: inhibitors targeting CD73, a key ectonucleotidase in the immunosuppressive adenosine pathway, and inhibitors targeting cellular Inhibitor of Apoptosis Proteins (cIAP), which modulate programmed cell death. These methodologies are presented within the broader research context of generating dendritic cells (DCs) from bone marrow for cancer immunotherapy, where small molecule inhibitors can be utilized to modulate the tumor microenvironment (TME) and enhance DC function [3] [30].

The CD39-CD73-adenosine axis represents a major immunosuppressive pathway in the TME. CD73, encoded by the NT5E gene, is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored ecto-5'-nucleotidase that catalyzes the conversion of AMP to adenosine, which subsequently suppresses immune effector cells via A2A receptor signaling [31] [32] [33]. Concurrently, IAP family proteins such as XIAP regulate apoptosis by inhibiting caspases 3, 7, and 9, with their overexpression linked to chemoresistance in various malignancies [34].

CD73 Small Molecule Inhibitors in Leukemia Microenvironment

CD73 Biological Function and Significance

CD73 serves as a pivotal immune checkpoint in leukemia through its role in generating immunosuppressive adenosine. In the leukemic microenvironment, extracellular ATP is sequentially hydrolyzed by CD39 (to AMP) and CD73 (to adenosine) [32] [33]. The resulting adenosine binds to A2A receptors on immune cells, triggering cAMP-mediated signaling that suppresses T-cell and NK-cell function while promoting regulatory T-cell (Treg) activity [31]. CD73 exists as both a membrane-anchored form (via GPI) and a soluble form, with its expression upregulated by hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) and inflammatory cytokines like TGF-β [33].

Beyond the canonical CD39-CD73 pathway, CD73 also contributes to adenosine production through the non-classical NAD+ pathway involving CD38 and CD203a (ENPP1) [33]. This alternative route is particularly relevant in hematological malignancies where CD38 is frequently expressed.

Table 1: CD73 Inhibitor Efficacy in Preclinical Leukemia Models

| Parameter | Finding | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Expression in Leukemia | Upregulated in various leukemia subtypes [33] | Human patient samples |

| Immunosuppressive Mechanism | Inhibits T cell and NK cell function; promotes Tregs [33] | In vitro co-culture assays |

| Therapeutic Targeting | Reduces adenosine-mediated immunosuppression [31] | Mouse leukemia models |

| Combination Potential | Synergizes with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors [33] | Preclinical studies |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing CD73 Inhibitor Effects on DC Function

Objective: To evaluate the effect of CD73 small molecule inhibitors on dendritic cell maturation and function in the context of leukemia-associated immunosuppression.

Materials:

- Mouse bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 mice

- GM-CSF (25 ng/mL)

- CD73 small molecule inhibitor (e.g., AB680 or OP-5244) [31]

- Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

- Flow cytometry antibodies: CD11c, I-A/I-E (MHC II), CD40, CD80, CD86, CCR7

- ELISA kits: IL-12, IFN-γ

Method:

- Bone Marrow-Derived DC (BMDC) Generation:

- Isolate bone marrow cells from mouse femurs and tibiae.

- Culture cells in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 2-mercaptoethanol, and 25 ng/mL GM-CSF for 6 days [3].

- Add CD73 inhibitor at optimal concentration (dose range: 0.1-10 µM) or vehicle control at day 0.

DC Maturation and Phenotypic Analysis:

- On day 6, stimulate cells with 10 ng/mL LPS for 12 hours.

- Harvest cells and stain with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD11c, MHC II, and co-stimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, CD86).

- Analyze marker expression on CD11c+ cells using flow cytometry.

- Assess CCR7 expression to evaluate migratory capacity.

Functional T Cell Activation Assay:

- Co-culture DCs with allogeneic or antigen-specific T cells at various ratios.

- Measure T cell proliferation via CFSE dilution or 3H-thymidine incorporation after 72-96 hours.

- Quantify IFN-γ production in supernatant by ELISA.

Adenosine Measurement:

- Collect culture supernatants from DC-T cell co-cultures.

- Measure adenosine concentrations using LC-MS or commercial adenosine assay kits.

- Correlate adenosine levels with T cell suppression.

Figure 1: CD73-mediated adenosine signaling pathway. CD39 and CD73 work sequentially to convert pro-inflammatory ATP to immunosuppressive adenosine, which activates A2AR signaling. CD73 inhibitors block the final step of adenosine production.

cIAP Small Molecule Inhibitors and XIAP Targeting

cIAP Biology and Therapeutic Targeting

X-linked Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein (XIAP), a member of the IAP family, directly binds and inhibits caspases 3, 7, and 9, thereby preventing apoptosis execution [34]. In leukemia and other cancers, downregulation of caspase-3 (CASP3/DR) often occurs alongside upregulation of caspase-7 (CASP7), leading to accumulation of the XIAP:CASP7 complex that promotes chemoresistance and cell survival [34].

Small molecule inhibitors targeting the XIAP:CASP7 interaction represent a promising strategy for selectively inducing apoptosis in CASP3/DR malignant cells while sparing normal cells that predominantly express CASP3. The reversible XIAP:CASP7 inhibitor 643943 was identified through virtual screening and validated to bind CASP7 at an allosteric site involving residues D93, A96, Q243, and C246, causing dissociation of XIAP and activation of CASP7-mediated apoptosis [34].

Table 2: cIAP/XIAP-Targeting Small Molecules in Cancer

| Compound | Target | Mechanism | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 643943 | XIAP:CASP7 interface | Reversible allosteric inhibitor; disrupts PPI | Induces selective apoptosis in CASP3/DR cells; in vivo efficacy [34] |

| I-Lys | Cys246 of CASP7 | Covalent alkylation; disrupts XIAP:CASP7 | Kills CASP3/DR cancer cells; re-sensitizes to chemotherapy [34] |

| SMAC Mimetics | BIR domains of IAPs | Mimic endogenous SMAC protein | Promote apoptosis; some toxicity to hematopoietic cells [34] |

Experimental Protocol: Targeting XIAP:CASP7 Complex in Leukemia Models

Objective: To assess the efficacy of XIAP:CASP7 PPI inhibitors in inducing selective apoptosis in caspase-3-deficient leukemia cells.

Materials:

- Leukemia cell lines (MCF-7 as CASP3/DR model; others with wild-type CASP3 as controls)

- XIAP:CASP7 inhibitor 643943 [34]

- Annexin V/PI apoptosis detection kit

- Caspase-7 activity assay kit

- Western blot reagents for XIAP, CASP7, CASP3, PARP

Method:

- Cell Culture and Compound Treatment:

- Maintain leukemia cell lines in appropriate media.

- Treat cells with serial dilutions of 643943 (0.1-100 µM) or vehicle control for 24-72 hours.

- Include positive control cells with reconstituted CASP3 expression.

Apoptosis Assessment:

- Harvest cells after treatment and stain with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide.

- Analyze by flow cytometry within 1 hour to quantify early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-) and late apoptotic/necrotic (Annexin V+/PI+) populations.

- Perform Western blotting for PARP cleavage to confirm apoptosis.

CASP7 Activity Measurement:

- Lyse cells after treatment with inhibitor.