Spatial Proteomics at Single-Cell Resolution: Unlocking Cellular Heterogeneity with DNA-Tagged Antibodies and Sequencing

This article explores the transformative field of spatial proteomics using DNA-tagged antibodies and sequencing, a technology that maps the precise location and interactions of proteins within individual cells.

Spatial Proteomics at Single-Cell Resolution: Unlocking Cellular Heterogeneity with DNA-Tagged Antibodies and Sequencing

Abstract

This article explores the transformative field of spatial proteomics using DNA-tagged antibodies and sequencing, a technology that maps the precise location and interactions of proteins within individual cells. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we cover the foundational principles of methods like Molecular Pixelation (MPX), detail cutting-edge workflows and applications in immunology and cancer research, address key troubleshooting and data analysis challenges, and provide a comparative analysis with mass spectrometry-based approaches. By synthesizing the latest advancements, this review serves as a comprehensive guide to leveraging spatial proteomics for uncovering novel biological mechanisms and driving innovations in precision medicine.

The Foundations of Spatial Proteomics: From Epitope Tagging to DNA-Encoded Antibodies

Defining Spatial Proteomics and Its Single-Cell Revolution

Spatial proteomics is an advanced multidimensional technique focused on exploring the spatial distribution and interactions of proteins within cells and tissues, while maintaining their native architectural context [1]. Unlike conventional proteomics, which homogenizes samples and consequently loses all spatial information, spatial proteomics allows researchers to study protein expression, localization, interactions, and post-translational modifications in a high-resolution, tissue-specific context [2]. This field has emerged as particularly powerful for understanding complex biological systems where location dictates function—such as in neural circuits, tumor microenvironments, and immune cell interactions [3] [4].

The single-cell revolution in spatial proteomics represents a paradigm shift in how researchers investigate cellular heterogeneity and function. While traditional transcriptomic approaches have revealed tremendous cellular diversity, proteins represent the actual functional effectors of cellular activity, with post-translational modifications and spatial organization critically influencing their function [5]. Recent technological innovations now enable researchers to map protein distributions and interactions at subcellular resolutions, providing unprecedented insights into cellular behavior in health and disease [6] [7]. This capability is especially crucial for understanding systems like the nervous system, which comprises one of the most complex tissues in the human body with functionally and anatomically segregated neuronal subpopulations and mosaic coexistence of glial cells [3].

Key Technological Platforms in Spatial Proteomics

The advancement of spatial proteomics has been driven by multiple technological platforms, each with unique strengths and applications. These approaches can be broadly categorized into imaging-based methods, mass spectrometry-based approaches, and sequencing-based techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Spatial Proteomics Technologies

| Technology | Principle | Samples | Advantages | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplexed Immunofluorescence (mIF) | Sequential staining with fluorescent antibodies | FFPE/FF | High specificity; multiple biomarkers | Fluorescence spectral overlap | [1] |

| CODEX | Antibody-DNA barcodes with multiple staining/elution cycles | FFPE/FF | Highly multiplexed detection; minimal fluorescence | Antibody dependency | [1] |

| Imaging Mass Cytometry (IMC) | Metal-tagged antibodies with laser ablation/ICP-MS | FFPE/FF | No fluorescence interference; higher resolution | Complex equipment; high cost | [1] [8] |

| Laser Capture Microdissection + MS (LCM-ScP) | Immunostaining-guided microdissection coupled with LC-MS | FFPE/FF | High precision; unbiased biomarker screening | Limited throughput | [3] |

| Molecular Pixelation (MPX) | DNA-tagged antibodies with proximity barcoding | Cell suspensions | Highly multiplexed 3D spatial analysis | Limited to surface proteins | [6] [9] |

| Deep Visual Proteomics (DVP) | AI-guided cell selection with ultrasensitive MS | FFPE/FF | Unbiased high proteome coverage; no antibody requirements | Technically challenging | [7] [4] |

DNA-Tagged Antibody and Sequencing Approaches

DNA-tagged antibody technologies represent a revolutionary approach that leverages nucleic acid sequencing rather than optical detection to achieve highly multiplexed spatial protein analysis. Techniques such as Molecular Pixelation (MPX) and CODEX utilize antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates (AOCs) to tag proteins of interest with unique DNA barcodes [6] [9].

The fundamental principle of Molecular Pixelation involves using AOCs bound to their protein targets on chemically fixed cells, followed by association of spatially proximate AOCs into local neighborhoods through unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) [6]. Specifically, each DNA pixel contains a concatemer of a UMI sequence called a unique pixel identifier (UPI) and is generated by rolling circle amplification from circular DNA templates. Once added to the reaction, each DNA pixel can hybridize to multiple AOC molecules in proximity on the cell surface, creating neighborhoods where AOCs within each neighborhood share the same UPI sequence [6]. After enzymatic degradation of the first DNA pixel set, a second set is similarly incorporated, enabling the reconstruction of spatial relationships through the overlap of UPI neighborhoods [6].

This approach enables highly multiplexed spatial analysis without the limitations of optical microscopy, achieving multiplexing capabilities for 76+ proteins simultaneously while providing nanometer-scale resolution [6]. The upper limit of resolution for MPX is approximately 280 nm, estimated by dividing the surface area of a lymphocyte by the average number of DNA pixels per cell [6]. Each sequenced molecule contains four distinct DNA barcode motifs: a UMI to identify unique AOC molecules, a protein identity barcode, and two UPI barcodes with neighborhood memberships [6].

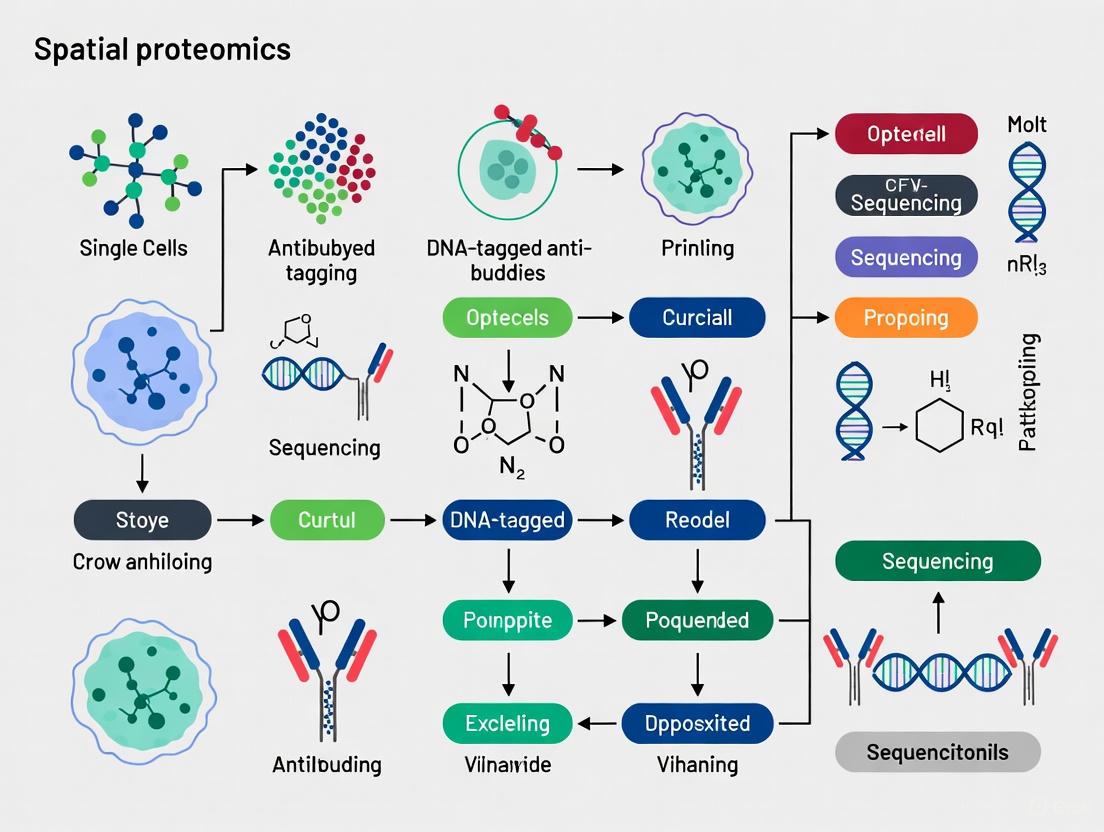

Figure 1: Molecular Pixelation Workflow for Spatial Proteomics

Mass Spectrometry-Based Approaches with Spatial Resolution

Mass spectrometry-based methods provide an unbiased approach to spatial proteomics without the requirement for specific antibodies. Techniques such as Laser Capture Microdissection coupled with Mass Spectrometry (LCM-ScP) and Deep Visual Proteomics (DVP) combine precise tissue sampling with sensitive proteomic analysis [3] [7].

The LCM-ScP workflow begins with tissue fixation (O.C.T. embedding and cryo-sectioning), followed by immunofluorescent staining to label cells of interest, facilitating pathology-guided selection for proteomic analysis [3]. Targeted cells are then isolated with precision using laser capture microdissection, enabling accurate excision of specific regions from tissue sections. The isolated cells are collected in a lysis buffer and subjected to digestion with a trypsin/Lys-C mix, a protocol optimized to enhance protein digestion efficiency in low-analyte samples [3]. Samples are then analyzed using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) with data-independent acquisition (DIA) modes to maximize protein identifications [3].

This approach has been successfully applied to characterize neuronal subtypes from distinct brain regions, with single neuronal cell bodies micro-dissected from areas such as the cortex and substantia nigra pars compacta for subsequent proteomic profiling [3]. The method yields consistent protein coverage across single-cell samples, with a maximum depth of 2,200 proteins quantified from a single cell, though greater heterogeneity is observed in single-cell samples compared to larger sample areas [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Details

LCM-ScP Protocol for Single-Cell Spatial Proteomics

The following detailed protocol for Laser Capture Microdissection Single-Cell Proteomics (LCM-ScP) has been optimized for neural tissue analysis [3]:

Sample Preparation Phase:

- Tissue Fixation and Sectioning: Fresh tissue is fixed with paraformaldehyde (PFA), embedded in O.C.T. compound, and cryo-sectioned at 35 μm thickness onto specialized membrane slides.

- Immunofluorescence Staining: Sections are stained with primary antibodies against target proteins (e.g., anti-NeuN for neurons), followed by appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies. All steps include rigorous controls to assess staining impact on proteome coverage.

- Validation Experiments: To confirm that fixation and staining don't introduce proteomic biases, comparative analyses are performed between fresh-frozen vs. fixed tissue, stained vs. unstained controls, and different staining methods (IHC vs. HCR).

Microdissection and Processing:

- Laser Capture Microdissection: Stained sections are visualized under a laser capture microdissection system. Single cells (~800 μm²) or cell populations are isolated using cold ablation laser cutting to prevent protein degradation.

- Sample Collection: Microdissected cells are collected directly into low-adsorption tubes containing 5 μL of lysis buffer (1% SDC in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5).

- Protein Digestion: Samples undergo reduction with 10 mM TCEP (30 min, 95°C), alkylation with 20 mM iodoacetamide (20 min, room temperature in dark), and digestion with trypsin/Lys-C mix (1:20 enzyme-to-protein ratio, 37°C overnight).

- Peptide Cleanup: Digested peptides are acidified with trifluoroacetic acid, desalted using StageTips, and eluted in 5 μL of LC-MS loading solvent.

LC-MS Analysis:

- Chromatographic Separation: Peptides are separated using a 1-hour nano-LC gradient optimized for single-cell applications (C18 column, 75 μm × 20 cm).

- Mass Spectrometry: Analysis is performed on a timsTOF SCP or similar instrument using data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode with 25 m/z isolation windows.

- Data Processing: DIA data are processed using spectral library-based approaches (DIA-NN, Spectronaut) against organism-specific protein databases.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Spatial Proteomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Oligo Conjugates | DNA-barcoded antibodies (MPX, CODEX) | Target protein recognition with sequenceable barcodes | Require validation of specificity and conjugation efficiency |

| Mass Tags | Metal-tagged antibodies (IMC), TMT tags (LC-MS) | Multiplexed protein detection and quantification | Isotopic purity, labeling efficiency |

| DNA Pixels | UPI-containing concatemers (MPX) | Spatial proximity recording through hybridization | Size optimization, hybridization specificity |

| Tissue Processing | PFA, O.C.T. compound | Tissue structure preservation and sectioning | Fixation time optimization, antigen retrieval |

| Digestion Enzymes | Trypsin/Lys-C mix | Protein digestion into measurable peptides | Enzyme-to-protein ratio, digestion time |

| LC-MS Materials | C18 columns, solvents | Peptide separation prior to mass spectrometry | Column chemistry, gradient optimization |

Molecular Pixelation Experimental Framework

The Molecular Pixelation (MPX) protocol for spatial analysis of cell surface proteins includes these critical steps [6]:

Cell Preparation and Staining:

- Cell Fixation: Primary cells or cell lines are fixed with 2% PFA for 20 minutes at room temperature.

- Antibody Staining: Cells are incubated with a panel of AOCs (1:100 dilution in PBS/0.5% BSA) for 60 minutes at room temperature.

- Washing: Unbound AOCs are removed by three washes with PBS/0.1% BSA.

Spatial Barcoding:

- First DNA Pixel Incubation: Cells are resuspended in reaction buffer containing the first set of DNA pixels and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Gap-Fill Ligation: Ligation mix is added, and the reaction proceeds for 60 minutes at 25°C to covalently link UPIs to nearby AOCs.

- Pixel Degradation: The first DNA pixel set is degraded using specific nucleases (30 minutes, 37°C).

- Second DNA Pixel Incorporation: Steps 1-3 are repeated with the second set of DNA pixels.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- PCR Amplification: Barcoded products are amplified using Illumina-compatible primers (15-18 cycles).

- Quality Control: Libraries are quantified using fragment analyzers or Bioanalyzer.

- Sequencing: Libraries are sequenced on Illumina platforms (NovaSeq 6000, 2×150 bp).

Data Analysis:

- Base Calling and Demultiplexing: Raw sequencing data are processed through Pixelator pipeline.

- Graph Construction: Spatial relationships are reconstructed as graph components with UPI sequences as nodes and protein identities as edge attributes.

- Spatial Analysis: Protein clustering, polarization, and co-localization are quantified using graph-based algorithms and spatial autocorrelation statistics.

Applications and Impact in Biomedical Research

Advancing Neuroscience Research

Spatial proteomics has proven particularly valuable for investigating the heterogeneous central nervous system, where functionally distinct neuronal populations are intermingled with diverse glial cell types [3]. LCM-ScP has been applied to compare neuronal populations from cortex and substantia nigra, two brain regions associated with motor and cognitive function and various neurological disorders [3]. This approach has enabled researchers to understand neuroimmune changes associated with stab wound injury and to compare the proteome of the myenteric plexus cell ganglion to the nerve bundle in the peripheral nervous system [3].

In Parkinson's disease research, spatial proteomics addresses a critical challenge: at later disease stages, only 1-2% of sparsely situated neurons in the cortex show pathological Lewy body aggregates [3]. Identifying perturbations in these specific neurons that bulk omics approaches fail to capture is essential for advancing our understanding of the disease mechanisms and developing targeted interventions [3].

Transforming Cancer Research and Immunotherapy

Spatial proteomics provides unprecedented insights into the tumor microenvironment, enabling researchers to study protein distribution and cell-cell interactions within tumor tissues [1] [7]. This technology has revealed spatially confined sub-tumor microenvironments in pancreatic cancer and multi-layered organization in glioblastoma, highlighting the intricate spatial architecture of tumors [4].

The application of spatial proteomics in immuno-oncology has been particularly impactful, with technologies like Digital Spatial Profiling (DSP) enabling spatial profiling of over 500 immuno-oncology relevant targets from Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissue sections [8]. This comprehensive profiling allows researchers to identify proteins or cell types linked to aggressive cancer, serving as new biomarkers, and to distinguish altered cancer pathways for targeted therapies [2].

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The field of spatial proteomics continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends and ongoing challenges. Multi-omics integration represents a major frontier, with researchers increasingly combining spatial proteomics with complementary technologies such as spatial transcriptomics and spatial epigenetic profiling to gain a more holistic understanding of biological complexity [7] [10]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is also transforming the field, from AI-guided cell selection in Deep Visual Proteomics to advanced computational tools for data analysis and interpretation [2] [10].

Technical challenges remain, particularly regarding sensitivity limitations in single-cell proteomics due to proteins' intrinsic "stickiness" that causes nonspecific adsorption to reaction vessels, resulting in sample losses during preparation steps [2]. The high costs associated with spatial proteomics instruments and the lack of skilled professionals also present barriers to widespread adoption [8]. However, the continuous technological improvements are addressing these limitations, with the spatial proteomics market projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 15.14% between 2025 and 2034, reflecting both increasing demand and technological advancement [2].

As the field matures, spatial proteomics is poised to become an indispensable tool in biomedical research, drug discovery, and clinical diagnostics, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective personalized therapies and advancing our fundamental understanding of cellular organization and function in health and disease.

The field of molecular biology has been profoundly shaped by the ability to tag and track proteins within their native environments. Traditional epitope tags, such as HA, Myc, and His-tags, revolutionized protein research by enabling purification, detection, and functional studies of recombinant proteins. While these methods remain fundamental, the increasing demand for multiplexed, spatial, and single-cell resolution in proteomic studies has catalyzed a paradigm shift toward DNA-based tagging technologies. This evolution is particularly critical in spatial proteomics, where understanding protein expression, interactions, and localization at subcellular levels across tissues and single cells provides unprecedented insights into cellular function in health and disease [10] [11].

The limitations of conventional tags are starkly evident in the context of modern spatial biology. Fluorescence-based detection, often coupled with HA or Myc tags, is constrained by spectral overlap, permitting simultaneous visualization of only a handful of proteins [12] [13]. The His-tag, while invaluable for purification, faces challenges of limited specificity in complex detection assays [14] [15]. In contrast, DNA barcoding technologies leverage the virtually unlimited encoding capacity of nucleic acid sequences, converting protein detection into a DNA sequencing problem. This transformation enables highly multiplexed protein profiling, integration with transcriptomic data, and the creation of spatial protein maps at single-cell resolution, thereby framing a new era in protein analysis [12] [6] [16].

The Foundational Era: Epitope and Affinity Tags

Traditional protein tags are short peptide sequences genetically fused to a protein of interest. They serve as handles for a variety of experimental manipulations.

Table 1: Characteristics of Traditional Protein Tags

| Tag Name | Amino Acid Sequence | Primary Application | Key Features and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| His-tag | HHHHHH (typically 6xHis) [14] | Affinity Purification via IMAC [14] [15] | Small size, binding to immobilized metal ions (Ni²âº, Co²âº); can have nonspecific binding [14] [15] |

| HA-tag | YPYDVPDYA | Immunodetection (Western Blot, IF) | High-affinity, well-characterized antibody; limited to a few targets per sample due to spectral overlap. |

| Myc-tag | EQKLISEEDL | Immunodetection (Western Blot, IF) | Similar to HA-tag; used for detection and immunoprecipitation. |

The His-Tag and Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC)

The His-tag is a workhorse for protein purification. Its principle relies on Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC), where the histidine residues coordinate with divalent metal ions like Nickel (Ni²âº) or Cobalt (Co²âº) immobilized on a resin [14] [15]. Nickel resins offer high binding capacity, whereas cobalt resins provide higher purity by reducing nonspecific binding of endogenous proteins with histidine clusters [15]. Elution is typically achieved by competition with imidazole (150-500 mM), protonation at low pH (e.g., pH 4 for nickel), or chelation of the metal ion with EDTA [14].

The Paradigm Shift: DNA Barcoding for Spatial Proteomics

DNA barcoding represents a fundamental departure from conventional tagging. Instead of using a peptide sequence recognized by an antibody or metal ion, a unique DNA oligonucleotide is conjugated to an antibody. This DNA barcode acts as a proxy for the antibody's target protein, converting a protein signal into an amplifiable, sequenceable DNA signal [12] [17]. This approach leverages the high diversity of DNA sequences to overcome the multiplexing limitations of fluorescence, enabling the simultaneous measurement of dozens to hundreds of proteins from a single sample [6] [13].

Key DNA Barcoding Technologies

Recent technological innovations have demonstrated the power of DNA barcoding in spatial proteomics.

- Multiplexed and Modular Barcoding of Antibodies (MaMBA): This strategy uses nanobodies as modular adaptors to site-specifically conjugate DNA oligos to off-the-shelf IgG antibodies. An enzymatic reaction catalyzed by Oldenlandia affinis asparaginyl endopeptidase (OaAEP1) ligates an azide-functionalized substrate to the nanobody, which is then coupled to DNA via a click reaction. The nanobody binds the Fc region of the IgG, avoiding interference with antigen binding. This method allows for the large-scale preparation of DNA-barcoded antibodies for highly multiplexed applications [12].

- Molecular Pixelation (MPX): MPX is an optics-free method for spatial proteomics of single cells. It uses antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates (AOCs) bound to cell surface proteins. The spatial arrangement of these AOCs is determined by sequentially associating them with unique DNA pixels (∼100 nm diameter) via hybridization and gap-fill ligation. Each DNA pixel contains a Unique Pixel Identifier (UPI), and the overlap of UPI neighborhoods from two serial reactions allows for computational reconstruction of protein spatial relationships on the cell surface for dozens of proteins simultaneously [6].

- Droplet-Based Single-Cell Barcoding: This approach combines DNA-barcoded antibodies with droplet microfluidics. Cells are stained with antibodies conjugated to DNA barcodes via chemical linkers (e.g., SM(PEG)₆). Individual cells are then co-encapsulated in droplets with barcodes containing unique cellular identifiers. Inside the droplet, a strand overlap extension PCR (SOE-PCR) links the protein-derived barcode with the cell barcode, creating a sequenceable molecule that records both the protein identity and its cell of origin, enabling high-throughput single-cell protein analysis [17].

Table 2: Comparison of DNA Barcoding Methods in Spatial Proteomics

| Method | Multiplexing Capacity | Spatial Resolution | Key Innovation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MaMBA [12] | High (demonstrated for 12 targets) | Tissue and subcellular (via imaging) | Nanobody-based modular DNA tagging | Multiplexed in situ protein imaging (misHCR) |

| Molecular Pixelation (MPX) [6] | Very High (76-plex panel demonstrated) | Nanometer-scale (280 nm estimated limit) | Proximity barcoding with DNA pixels | Single-cell surface protein spatial networks |

| Droplet Barcoding [17] | High | Single-cell (no subcellular information) | Microfluidic single-cell compartmentalization | Single-cell protein quantitation alongside transcriptomics |

| Stereo-cell [18] | High (multimodal) | Near-subcellular (~500 nm DNB spacing) | DNA nanoball-patterned arrays for spatial capture | Integrated spatial transcriptomics and proteomics |

Experimental Protocols: Implementing DNA Barcoding

This protocol describes the site-specific conjugation of DNA oligos to nanobodies for modular antibody barcoding.

- Enzymatic Labeling of Nanobody: Incubate the nanobody (with C-terminal NGL motif) with the OaAEP1 enzyme and an azide-bearing dipeptide substrate (Gly-Val). This catalyzes the ligation of the azide functional group to the nanobody.

- Purification: Remove excess enzyme and substrate via standard protein purification techniques (e.g., spin columns).

- Click Reaction for DNA Conjugation: React the azide-functionalized nanobody with a DBCO-modified DNA oligonucleotide (containing the HCR initiator sequence) via a copper-free click reaction.

- Quality Control: Analyze conjugation efficiency using SDS-PAGE. The resulting Nb-DNA oligo conjugates can be stored for later use.

- Assembly with Primary Antibody: Combine the DNA-conjugated nanobody with an off-the-shelf IgG primary antibody. The nanobody binds the Fc region, forming the final Ab-HCR initiator complex ready for application.

This protocol outlines the steps for determining the spatial organization of cell surface proteins on single cells.

- Cell Staining and Fixation: Chemically fix cells (e.g., with PFA) and stain with a panel of antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates (AOCs).

- First DNA Pixel Incorporation: Incubate stained cells with the first set of DNA pixels. Each pixel hybridizes to multiple proximate AOCs, and its Unique Pixel Identifier (UPI-A) is incorporated onto the AOC oligonucleotide via a gap-fill ligation reaction.

- Pixel Degradation and Second Incorporation: Enzymatically degrade the first set of DNA pixels. Repeat the process with a second set of DNA pixels, incorporating a second UPI (UPI-B) onto the AOCs.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Amplify the resulting constructs by PCR and sequence using next-generation sequencing.

- Data Analysis: Use the Pixelator pipeline to process sequence reads. Construct graphs where UPI sequences are nodes and protein identities are edge attributes. Each connected graph component represents a single cell, from which spatial relationships (clustering, colocalization) are inferred.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for DNA Barcoding

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Barcoding Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Nanobodies (e.g., TP897, TP1107) [12] | Modular adaptors that bind IgG Fc regions; enable site-specific DNA conjugation to any off-the-shelf antibody. | MaMBA protocol for creating DNA-barcoded primary antibodies. |

| OaAEP1 Enzyme [12] | Asparaginyl endopeptidase that catalyzes site-specific ligation of a dipeptide substrate to a protein tag. | Creating azide-functionalized nanobodies for subsequent click chemistry. |

| Antibody-Oligonucleotide Conjugates (AOCs) [6] | Primary antibodies directly conjugated to DNA oligonucleotides; define the target protein panel. | Molecular Pixelation (MPX) for spatial proteomics of single cells. |

| DNA Pixels [6] | Rolling circle amplification products containing a Unique Pixel Identifier (UPI); act as molecular rulers for proximity barcoding. | Defining spatial neighborhoods of AOCs in the MPX workflow. |

| Microfluidic Droplet Generator [17] | Device for generating monodisperse water-in-oil droplets; used for single-cell compartmentalization and barcoding. | Droplet-based single-cell protein profiling and multi-omic studies. |

| IMAC Resins (Ni-NTA, Co²âº) [14] [15] | Agarose or magnetic beads charged with metal ions for purifying His-tagged recombinant proteins. | Purification of recombinant enzymes like OaAEP1 or nanobodies. |

| Antradion | Antradion, CAS:19854-90-1, MF:C33H31N3O4, MW:533.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Antroquinonol | Antroquinonol, CAS:1010081-09-0, MF:C24H38O4, MW:390.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of Workflows and Signaling

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationships and workflows of key DNA barcoding technologies.

MaMBA Workflow for Antibody Barcoding

Molecular Pixelation (MPX) Spatial Mapping

The evolution from HA, Myc, and His-tags to DNA barcodes marks a transformative period in protein science, directly fueling the ascent of spatial proteomics. This shift is not merely a change in label composition but a fundamental reimagining of protein detection, moving from analog, low-plex optical signals to digital, highly multiplexed sequence-based signals. The integration of these technologies with single-cell sequencing, microfluidics, and advanced computational analysis enables the deconvolution of cellular heterogeneity and the mapping of protein networks with nanometer-scale precision [6] [18].

Future developments will focus on increasing multiplexity further, improving detection sensitivity, and standardizing protocols for robust clinical translation. Platforms like Stereo-cell that integrate spatial transcriptomics and proteomics are already paving the way for a more holistic view of cellular states [18]. Furthermore, the application of artificial intelligence to analyze the complex, high-dimensional data generated by these methods will be crucial for extracting biologically and clinically actionable insights [10] [18]. As these DNA-based tagging and barcoding technologies mature, they will undoubtedly become central tools in the quest to understand complex biological systems, accelerate drug discovery, and realize the promise of precision medicine.

In the evolving landscape of spatial proteomics, the ability to map the precise location and interaction of proteins within a single cell is paramount for understanding cellular function in health and disease. Traditional methods for protein detection, such as fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry, are fundamentally limited in their multiplexing capacity by the spectral overlap of fluorescent tags, typically allowing simultaneous assessment of only a few proteins. The integration of DNA-tagged antibodies with next-generation sequencing (NGS) has shattered this barrier, transforming proteins into sequence-readable entities. This paradigm shift enables the highly multiplexed, spatial detection of dozens to hundreds of proteins, providing unprecedented insights into the molecular architecture of single cells and opening new avenues for drug discovery and diagnostic applications [6] [19].

This technical guide details the core principles, methodologies, and key reagents that underpin this powerful approach, framing it within the context of advanced spatial proteomics research.

Core Principle: Converting Protein Signal to DNA Sequence

The fundamental concept behind DNA-tagged antibody methods is the replacement of a fluorescent dye with a synthetic DNA oligonucleotide. This "DNA barcode" serves as a unique, amplifiable proxy for the antibody and, by extension, its protein target.

- Antibody-DNA Conjugation: A monoclonal antibody is covalently linked to a single-stranded DNA molecule. This DNA strand contains a unique protein identity barcode that corresponds to the antibody's target protein.

- Binding and Staining: A pooled library of these DNA-tagged antibodies is incubated with a sample (e.g., fixed cells or tissue). Each antibody binds specifically to its target epitope.

- Signal Readout via NGS: Instead of measuring light emission, the bound antibodies are detected by amplifying and sequencing their unique DNA barcodes using NGS. The resulting read counts for each barcode provide a quantitative measure of protein abundance [19].

This conversion from an analog protein signal to a digital DNA sequence leverages the vast sequence space of DNA, allowing for extreme multiplexing far beyond the limits of optical spectroscopy.

Key Methodological Frameworks

Several sophisticated techniques have been built upon this core principle to extract spatial and quantitative protein data. The following section details two prominent methodologies.

Method 1: Molecular Pixelation (MPX) for Spatial Proteomics

Molecular Pixelation (MPX) is an optics-free method designed specifically for mapping the 3D spatial organization of cell surface proteins at the single-cell level [6].

Experimental Protocol

- Staining: Chemically fixed cells are stained with a panel of antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates (AOCs).

- Association with DNA Pixels: The stained cells are incubated with "DNA pixels," which are nanometer-sized DNA concatemers containing a Unique Pixel Identifier (UPI) sequence, generated by rolling circle amplification. These pixels hybridize to multiple spatially proximate AOCs on the cell surface.

- Gap-Fill Ligation: A enzymatic reaction covalently links the UPI sequence from the DNA pixel onto the oligonucleotides of the hybridized AOCs. This creates "neighborhoods" of AOCs that share the same UPI.

- Pixel Exchange: The first set of DNA pixels is enzymatically degraded and a second set is introduced and incorporated via another round of hybridization and ligation. This two-step process creates two overlapping neighborhood membership lists (UPI-A and UPI-B) for each AOC.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Cells are subjected to PCR to amplify the AOC constructs, which now contain the original protein barcode and the two UPI barcodes. The resulting libraries are sequenced on an NGS platform.

- Spatial Network Reconstruction: Sequencing reads are processed computationally. Each unique AOC molecule is represented as an edge in a bipartite graph, with UPI-A and UPI-B sequences as nodes. The graphs are separated into components representing individual cells, and the spatial relationships of proteins are inferred through graph theory and spatial statistics, such as calculating polarity scores via Moran's I autocorrelation statistic [6].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Outputs from a Representative MPX Study [6]

| Metric | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Proteins Assayed | 76 | Multiplexing capacity of the AOC panel targeting immune cell proteins. |

| Average DNA-pixel A Zones per Cell | 1,737 | Number of distinct spatial neighborhoods mapped per cell. |

| Average AOC UMIs per Cell | 9,580 | Total number of unique antibody binding events detected per cell. |

| Average UMIs per UPI-A Pixel | 5.6 | Measure of the density of antibody tags within a local neighborhood. |

| Estimated Resolution | < 280 nm | Upper limit of spatial resolution for a lymphocyte cell. |

Method 2: Split-Pool Sequencing (QBC2) for Protein Quantification

This combinatorial indexing method, an implementation of Quantum Barcoding (QBC2), focuses on high-throughput, quantitative single-cell proteomics without the need for specialized microfluidic instrumentation [19].

Experimental Protocol

- Staining: Cells are stained with a pool of DNA-barcoded antibodies.

- First-Round Split-Pool:

- Split: The stained cell suspension is randomly distributed into a multi-well plate (e.g., a 96-well plate).

- Ligation: In each well, a universal splint primer facilitates the ligation of a unique "well barcode 1" to the 3' end of all DNA-barcoded antibodies present.

- Blocking: A complementary oligo is added to block the splint primer and prevent mis-ligation in subsequent steps.

- Pool: Cells from all wells are combined into a single tube.

- Second-Round Split-Pool:

- Split: The pooled cells are randomly redistributed into a new multi-well plate.

- Ligation: A second unique "well barcode 2" is ligated to the antibodies using a different splint primer.

- Blocking and Pool: The splint is blocked again, and cells are pooled.

- PCR and Sequencing:

- Split: Cells are distributed into a final PCR plate.

- Amplification: PCR is performed, which both amplifies the construct and appends a third "well barcode 3" via the primer.

- Pool and Sequence: The PCR products from all wells are pooled and prepared for NGS.

- Data Analysis: Each sequenced read contains the antibody barcode and the trio of well barcodes. All reads sharing the same combination of three well barcodes are assigned to a single cell of origin. The protein expression profile for each cell is constructed by counting the antibody barcodes associated with its unique barcode trio [19].

Visualizing the Core Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationships and experimental workflows for the two primary methods described above.

Diagram 1: Molecular Pixelation (MPX) Workflow

Diagram 2: Split-Pool Barcoding (QBC2) Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of DNA-tagged antibody assays relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table catalogues the essential components for building these experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA-Tagged Antibody Assays

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Oligonucleotide Conjugates (AOCs) | Primary detection reagent that binds target protein and carries a unique DNA barcode. | Can be site-specifically conjugated to preserve antibody affinity and specificity [6] [12]. |

| DNA Pixels (for MPX) | Rolling circle amplification products containing a Unique Pixel Identifier (UPI); used to define spatial neighborhoods. | Nanometer-sized concatemers that hybridize to multiple proximate AOCs, enabling spatial inference [6]. |

| Splint Oligos & DNA Barcodes (for QBC2) | Short DNA oligonucleotides that facilitate the ligation of unique well barcodes to AOCs during split-pool steps. | Universal splint primers enable modular and efficient barcode ligation [19]. |

| Nanobody-DNA Adaptors (MaMBA) | Modular adaptors (e.g., Fc-binding nanobodies) that are pre-conjugated with DNA barcodes, enabling rapid, site-specific barcoding of off-the-shelf IgG antibodies. | Simplifies reagent generation and minimizes affinity loss compared to direct chemical conjugation [12]. |

| Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) Amplifiers | Fluorescent DNA nanostructures that bind to AOC barcodes for signal amplification in imaging applications (e.g., misHCR). | Provides high signal-to-noise for highly multiplexed in situ protein imaging [12]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencer | Universal endpoint for digital readout of all DNA barcodes. | Illumina short-read systems are commonly used for their high accuracy and throughput [20] [21]. |

| Aplindore Fumarate | Aplindore Fumarate|Dopamine D2 Receptor Agonist|RUO | |

| (R)-Norverapamil | (R)-Norverapamil, CAS:123932-43-4, MF:C26H36N2O4, MW:440.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The fusion of immunology and sequencing technology through DNA-tagged antibodies has fundamentally expanded the horizons of proteomics. By transcending the multiplexing limits of fluorescence, these methods empower researchers to deconvolve cellular heterogeneity at a systems level. Core techniques like Molecular Pixelation (MPX) provide a groundbreaking, optics-free path to spatial proteomics by constructing graph-based maps of protein organization, while methods like split-pool barcoding (QBC2) offer accessible, highly scalable routes to quantifying protein abundance in single cells.

As these technologies continue to mature, supported by robust reagent kits and sophisticated computational pipelines, they are poised to become standard tools in biomedical research. Their application will undoubtedly accelerate the discovery of novel drug targets, illuminate disease mechanisms with unprecedented clarity, and refine diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in the era of precision medicine.

The field of spatial proteomics is undergoing a revolutionary transformation, driven by the convergence of advanced sequencing technologies, high-resolution mass spectrometry, and sophisticated computational biology. This integration is enabling researchers to map the proteomic landscape of tissues with single-cell resolution, preserving the crucial spatial context that governs cellular function and dysfunction in disease. The core objective of modern spatial biology is to analyze cells within their native microenvironment, integrating data on morphology, gene expression, and protein localization [22]. Technological advancements are now making it possible to achieve this holistically, adding critical layers of metabolic and lipid information through techniques like mass spectrometry imaging [22]. This technical guide examines the key drivers powering this evolution, providing a detailed analysis of the methodologies and applications shaping contemporary single-cell spatial proteomics research.

Core Technological Pillars

Advanced Sequencing Technologies

Next-generation sequencing has expanded beyond genomics to become a cornerstone of protein analysis through DNA-barcoded antibody technologies. These methods leverage the high-throughput and multiplexing capabilities of modern sequencing platforms to quantify protein abundance and localization simultaneously with transcriptomic information.

The scEpi2-seq method exemplifies this convergence, enabling joint profiling of histone modifications and DNA methylation at single-cell resolution. This technique utilizes TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS) for multi-omic readout, where protein A-micrococcal nuclease (pA-MNase) is tethered to specific histone modifications via antibodies [23]. Following MNase digestion, fragments are processed with adaptors containing cell barcodes and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), then subjected to TAPS conversion which selectively modifies methylated cytosine to uracil while preserving adaptor integrity [23]. This approach achieves high-quality multi-omic data with specificity metrics (FRiP) ranging between 0.72-0.88 across different histone marks while detecting over 50,000 CpGs per single cell [23].

For pure protein detection, DNA-barcoded antibody sequencing methods utilize oligonucleotide-conjugated antibodies that are detected through high-throughput sequencing platforms like the UG 100 system, which employs silicon wafer-based sequencing to dramatically increase throughput and reduce costs [24]. These approaches are powering massive-scale proteomic studies, such as the UK Biobank's initiative to measure up to 5,400 proteins in each of 600,000 samples [25].

Mass Spectrometry and Imaging Innovations

Mass spectrometry has evolved from bulk protein analysis to sophisticated single-cell and spatial applications through multiple technological breakthroughs.

High-Resolution Single-Cell Proteomics now routinely identifies over 5,000 proteins per cell using advanced platforms like the Astral mass spectrometer [26]. Two primary data acquisition strategies dominate the field:

- Data-Dependent Acquisition with Tandem Mass Tags (DDA-TMT) enables multiplexing of up to 35 samples simultaneously, significantly increasing throughput by analyzing multiple single cells in parallel within a single LC-MS run [26]. However, this approach suffers from ratio compression and co-isolation interference, which can distort quantification.

- Data-Independent Acquisition with Label-Free Quantification (DIA-LFQ) independently measures peptide abundances in each sample, eliminating inter-sample interference and providing more accurate quantification, wider dynamic range, and improved sensitivity for low-copy proteins, though at the cost of lower throughput [26].

Spatial Mass Spectrometry Imaging technologies, particularly matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI-MSI), have achieved pixel sizes of 1×1 μm² through transmission-mode implementations with laser postionization (t-MALDI-2-MSI) [22]. This subcellular resolution enables the correlation of lipid distributions with specific cellular compartments and processes, such as visualizing intracellular lipid distributions in macrophages during phagocytosis [22]. The integration of in-source bright-field and fluorescence microscopy with MALDI-MSI creates a powerful multimodal platform that inherently co-registers both modalities by utilizing the same coordinate system for imaging and mass spectrometry [22].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Single-Cell Proteomics Methods

| Method | Proteins/Cell | Throughput | Quantitative Accuracy | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDA-TMT | 1,500-3,000 | High (multiplexed) | Moderate (ratio compression) | High-throughput screening, population studies |

| DIA-LFQ | 3,000-5,000+ | Moderate (single cells) | High (minimal interference) | Deep proteome coverage, low-abundance proteins |

| MALDI-MSI | Hundreds of lipids/metabolites | Spatial mapping | Semi-quantitative | Spatial distribution, tissue microenvironment |

Computational Biology and AI Integration

The immense complexity and volume of data generated by modern spatial proteomics technologies necessitates equally advanced computational approaches. Artificial intelligence and machine learning have become indispensable tools for processing, interpreting, and extracting biological insights from these datasets.

Machine Learning-Enhanced Spatial Analysis employs convolutional neural networks to detect local patterns in spatial omics datasets, enabling the identification of distinct cellular microenvironments and neighborhood relationships within tissues [27]. These approaches are particularly valuable in oncology, where they can reveal tumor heterogeneity and complex tumor-immune interactions that predict clinical outcomes and therapeutic responses [27].

Data Processing and Integration platforms face unique challenges in proteomics, where the absence of protein amplification creates low-signal, sparse data structures that require specialized normalization and imputation workflows [26]. Modern proteomics LIMS (Laboratory Information Management Systems) now incorporate AI-assisted peak annotation that reduces data processing time by up to 60% while improving consistency across operators [28]. These systems provide native integration with specialized proteomic analysis software including MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer, and PEAKS, creating closed-loop automation that reduces human error while accelerating discovery timelines [28].

Multi-Omic Data Integration represents the cutting edge of computational biology, with knowledge graph technology visualizing relationships between proteins, pathways, and experimental conditions to reveal insights hidden in conventional storage approaches [28]. This integration is essential for bridging different analytical modalities, such as correlating protein expression data from MALDI-MSI with transcriptional activity from spatial transcriptomics to build comprehensive models of cellular function within tissue architecture.

Integrated Experimental Workflows

Single-Cell Multi-Omic Profiling

The scEpi2-seq protocol represents a sophisticated integration of sequencing and proteomic approaches for simultaneous analysis of histone modifications and DNA methylation. The detailed methodology involves:

- Cell Isolation and Permeabilization: Single cells are isolated using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) into 384-well plates, followed by permeabilization to enable antibody access [23].

- Antibody Binding: A protein A-MNase fusion protein is tethered to specific histone modifications using validated antibodies with high specificity [23].

- MNase Digestion: Calcium addition initiates MNase digestion, generating fragments from nucleosomes bearing the targeted histone modifications [23].

- Library Preparation: Fragments are repaired, A-tailed, and ligated to adaptors containing cell barcodes, UMIs, T7 promoters, and Illumina handles [23].

- TAPS Conversion: TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing converts methylated cytosine to uracil while preserving adaptor integrity, unlike traditional bisulfite approaches [23].

- Sequencing and Analysis: Following in vitro transcription, reverse transcription, and PCR amplification, paired-end sequencing simultaneously maps histone modification positions through fragment locations and DNA methylation through C-to-T conversions [23].

This integrated approach reveals fundamental biological relationships, such as the finding that regions marked by repressive histone modifications (H3K27me3 and H3K9me3) show much lower DNA methylation levels (8-10%) compared to active regions marked by H3K36me3 (50%) [23].

Spatial Proteomics with Integrated Microscopy and MSI

The integration of transmission-mode MALDI-2 with in-source microscopy represents a groundbreaking approach for correlative spatial biology:

- Sample Preparation: Fresh-frozen tissue sections are prepared with dedicated staining protocols optimized to minimize chemical alterations and spatial delocalization. Small molecule stains target nuclei and F-actin, while immunofluorescence detects specific proteins like calbindin in Purkinje cells [22].

- Pre-MSI Fluorescence Microscopy: Slide scanning fluorescence microscopy is performed prior to matrix application at high magnification (50X) to capture reference images of staining patterns and tissue morphology [22].

- Matrix Application: Matrix is applied through resublimation to preserve spatial relationships and maintain analytical sensitivity for lipids and metabolites [22].

- In-Source Microscopy and MSI: The sample is transferred to the MALDI ion source where integrated bright-field and fluorescence microscopy share essential optical components with the laser ablation system. This design inherently co-registers both modalities through a shared coordinate system, achieving deviations of less than 1μm [22].

- t-MALDI-2-MSI Acquisition: Data acquisition at 1×1 μm² pixel size in positive ion mode using laser postionization to enhance sensitivity, particularly for lipid species [22].

- Data Correlation and Analysis: Molecular ion distributions from MSI are directly correlated with microscopic features, enabling the association of specific lipid profiles with individual cells and subcellular structures within their tissue context [22].

This workflow has revealed striking biological phenomena, including the heterogeneity of lipid profiles in tumor-infiltrating neutrophils correlated to their individual microenvironments [22].

Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

The advancement of spatial proteomics research depends on specialized reagents, instruments, and computational tools that enable these sophisticated analyses.

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for Spatial Proteomics

| Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Key Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | timsTOF-fleX with MALDI-2, Astral, Orbitrap | High-sensitivity protein/peptide detection | Astral platform enables >5,000 proteins/cell identification [26] |

| Sample Preparation Systems | cellenONE, ProteoCHIP | Automated single-cell dispensing/nanoliter handling | Minimizes surface adsorption losses for low-abundance proteins [26] |

| Multiplexing Reagents | Tandem Mass Tags (TMT) | Multiplex sample analysis | Enables pooling of up to 35 single cells for parallel processing [26] |

| Spatial Biology Platforms | Phenocycler Fusion (Akoya), COMET (Lunaphore) | Highly multiplexed protein imaging | Enables visualization of dozens of proteins in same sample [24] |

| Antibody Resources | Human Protein Atlas | Validated antibodies for spatial mapping | Near proteome-wide collection for subcellular localization [24] |

| Computational Tools | MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer, PEAKS | MS data processing and analysis | Integrated LIMS solutions reduce processing time by 40-60% [28] |

| Sequencing Platforms | UG 100 (Ultima Genomics), Illumina systems | DNA barcode reading for antibody detection | Silicon wafer-based sequencing increases throughput, reduces cost [24] |

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

The integration of sequencing, mass spectrometry, and computational biology is enabling transformative applications across biomedical research and clinical translation.

In oncology, spatial proteomics has revealed profound insights into tumor heterogeneity and the tumor microenvironment that were previously obscured by bulk analysis approaches. These technologies can map protein expression and interactions within intact tissues, providing valuable information for patient stratification, therapeutic response prediction, and novel target identification [27]. The ability to characterize rare cell populations and transitional states within tumors is particularly valuable for understanding mechanisms of therapy resistance and disease progression.

In neuroscience, the correlation of lipid distributions with specific cell types in complex tissues like mouse cerebellum demonstrates the power of integrated spatial biology approaches. The combination of immunofluorescence targeting specific neuronal markers (e.g., calbindin in Purkinje cells) with untargeted lipidomics reveals cell-type-specific metabolic signatures and their spatial organization within neural circuits [22].

The field is rapidly advancing toward true single-cell spatial proteomics, with MSI platforms now achieving 5-10 μm spatial resolution that approaches cellular dimensions [27]. Emerging methods such as multiplexed MALDI-IHC, tissue expansion techniques, and integrative multi-omics platforms are pushing these boundaries further, driving the creation of comprehensive spatial tissue atlases that capture molecular information across multiple scales [27].

The market dynamics reflect this rapid technological evolution, with the global proteomics market projected to grow from $31.41 billion in 2025 to $93.48 billion by 2034, representing a compound annual growth rate of 12.94% [25]. This expansion is fueled by increasing investments in R&D, the transition toward personalized medicine, and the growing prevalence of chronic diseases requiring sophisticated molecular characterization [29].

As these technologies continue to mature, the integration of sequencing, mass spectrometry, and computational biology will undoubtedly uncover new biological mechanisms and transform our approach to diagnosing and treating complex diseases.

The intricate organization of proteins within a single cell is a fundamental regulator of cellular activity, yet it remains one of the most challenging frontiers in biology. Spatial proteomics has emerged as a powerful discipline dedicated to mapping the subcellular location, interaction, and organization of proteins, providing critical insights that transcend what can be learned from abundance measurements alone [30]. The concept that a protein's location defines its function is paramount; for instance, the mislocalization of proteins is a known contributor to diseases such as Alzheimer's, cystic fibrosis, and cancer [31] [32]. Understanding cellular heterogeneity requires moving beyond bulk analyses to techniques that can resolve protein networks at the single-cell level, as variations between individual cells within a tissue can drive profound functional differences, including drug resistance in tumors [33]. This technical guide explores how cutting-edge methods, particularly those utilizing DNA-tagged antibodies and sequencing, are revolutionizing our capacity to resolve cellular heterogeneity by revealing the spatial proteomic landscape of individual cells within their native tissue context.

The Critical Role of Protein Location in Cellular Heterogeneity

Protein Mislocalization in Human Disease

A protein's function is intrinsically linked to its precise location within the cell. When this spatial organization is disrupted, it can have severe pathological consequences. For example, a protein located in the wrong part of a cell can contribute to several diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's and various cancers [31]. This mislocalization underscores why simply knowing a protein's identity or abundance is insufficient for a complete understanding of its role in health and disease. Comprehensive mapping efforts, such as the Human Protein Atlas Cell Atlas, which has mapped over 12,000 proteins across 22 cell types, are reinforcing the link between protein mislocalization and disease [32]. As Professor Emma Lundberg of Stanford University and the Cell Atlas project notes, this resource helps dismantle the outdated notion of "one gene, one protein, one function," as researchers increasingly discover that many proteins have multiple localizations and consequently, multiple roles [32].

The Challenge of Tumor Heterogeneity

In oncology, spatial organization of proteins governs vital cellular processes. In the immune system, for instance, the spatial distribution of cell surface proteins dictates intercellular communication, mobility, and T cell effector function [6]. Tumor heterogeneity presents a major challenge in clinical trials and treatment, as differences between tumors and even within a single tumor can drive drug resistance [33]. These spatial variations occur within tumors, across primary and metastatic sites, and evolve over disease progression. Traditional methods like single-gene biomarkers or histology often fail to capture this complexity, necessitating spatial proteomics approaches that can resolve the functional organization of complex cellular ecosystems within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [33].

Table 1: Key Biological Processes Governed by Protein Spatial Organization

| Biological Process | Spatial Requirement | Cellular Context |

|---|---|---|

| Immune Cell Signaling | Dynamic tuning of receptor organization | T cell activation, response to chemokines [6] |

| Cell-Cell Communication | Juxtaposition of surface receptors | Immune synapse formation [6] |

| Cell Mobility | Polarization of adhesion receptors | Cancer metastasis, immune cell trafficking [6] [34] |

| Drug Mode-of-Action | Target accessibility and complex formation | Response to targeted therapies [6] |

| Therapy Efficacy | Spatial organization of target antigens | Cellular therapies like CAR-T [6] |

Advanced Spatial Proteomics Technologies

Molecular Pixelation: DNA-Based Spatial Proteomics

Molecular Pixelation (MPX) is an optics-free, DNA sequence-based method for spatial proteomics of single cells. It uses antibody–oligonucleotide conjugates (AOCs) and nanometer-sized DNA molecules called "molecular pixels" to determine the relative locations of hundreds of proteins simultaneously without microscopy [6] [9]. The assay is performed without sample immobilization or single-cell compartmentalization in a standard reaction tube. AOCs bound to their protein targets on fixed cells are associated into local neighborhoods through DNA pixels, each containing a unique pixel identifier (UPI). Through two serial rounds of DNA pixel hybridization and gap-fill ligation, spatial relationships are encoded into DNA sequences that can be read via next-generation sequencing [6]. The resulting data for each single cell can be represented as a graph, where spatial statistics can identify patterns like protein clustering or colocalization. MPX can generate spatial networks for over 76 proteins, creating >1,000 spatially connected zones per cell in 3D [6] [9].

AI-Driven Prediction of Protein Localization

Computational approaches are complementing experimental methods in spatial proteomics. PUPS (Prediction of Unseen Proteins' Subcellular Location) is a novel AI-based method that can predict the location of any protein in any human cell line, even when both the protein and cell type have never been tested experimentally [31]. This model combines a protein language model (understanding protein sequence and structure) with a computer vision model (analyzing cell state from stained images) to output a prediction of protein location highlighted on an image of a cell. Unlike many methods that require prior experimental data for a specific protein, PUPS can generalize to unseen proteins and cell lines, capturing changes in localization driven by unique protein mutations [31]. This capability is particularly valuable for studying rare proteins or mutations not yet cataloged in databases like the Human Protein Atlas.

Tissue-Specific Protein Association Atlas

Large-scale proteomic datasets are enabling the systematic mapping of protein interactions across tissues. One recent resource compiled and analyzed 7,811 proteomic samples from 11 human tissues to produce an atlas of tissue-specific protein associations [34]. The method is based on the principle that protein coabundance is predictive of functional association, as protein complexes consist of subunits assembled in defined stoichiometries. This atlas scores the likelihood of 116 million protein pairs across the 11 tissues, finding that over 25% of associations are tissue-specific [34]. Such resources are invaluable for understanding cell-type-specific function, identifying drug targets, and prioritizing candidate disease genes in a tissue-relevant context, such as constructing a network of brain interactions for schizophrenia-related genes [34].

Table 2: Comparison of Spatial Proteomics Methodologies

| Methodology | Multiplexing Capacity | Resolution | Key Output | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Pixelation (MPX) | High (76+ proteins) | ~280 nm (estimated) | Single-cell spatial graphs | High (1000s of cells) [6] |

| AI Prediction (PUPS) | Virtually unlimited | Single-cell (predicted) | Localization prediction image | Very High (computational) [31] |

| Coabundance Atlas | Proteome-wide | Tissue-level (bulk) | Tissue-specific association scores | Population-scale [34] |

| Fluorescence Microscopy | Low (~4 targets/cycle) | Diffraction-limited (~200 nm) | Optical images | Low to Medium [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Spatial Proteomics

Molecular Pixelation (MPX) Workflow Protocol

The MPX protocol enables highly multiplexed spatial proteomics without optical imaging, using DNA sequencing as the readout [6]:

- Cell Preparation and Fixation: Isolate cells of interest (e.g., PBMCs from healthy donor) and fix with paraformaldehyde (PFA) to preserve protein organization.

- Staining with AOCs: Incubate fixed cells with a panel of antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates (AOCs). Each AOC consists of an antibody targeting a specific cell surface protein conjugated to a unique DNA oligonucleotide.

- First DNA Pixel Incorporation: Add the first set of DNA pixels—nanometer-sized single-stranded DNA molecules generated by rolling circle amplification, each containing a unique pixel identifier (UPI-A). The DNA pixels hybridize to multiple spatially proximate AOCs on the cell surface. Perform a gap-fill ligation reaction to incorporate the UPI-A sequence onto the AOC oligonucleotides, creating the first set of neighborhoods (AOCs sharing the same UPI-A are spatially proximal).

- Enzymatic Degradation: Degrade the first set of DNA pixels enzymatically to prepare for the second round of labeling.

- Second DNA Pixel Incorporation: Add a second set of DNA pixels with different UPI sequences (UPI-B). Repeat the hybridization and gap-fill ligation to create a second, independent set of neighborhoods.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Amplify the resulting amplicons by PCR and sequence using next-generation sequencing platforms.

- Computational Analysis: Process sequenced reads using the open-source Pixelator pipeline to reconstruct spatial relationships. Each sequenced molecule contains a UMI (identifying unique AOC molecules), a protein identity barcode, and two UPI barcodes (UPI-A and UPI-B). The relative location of each unique AOC molecule is inferred from the overlap of UPI neighborhoods, generating bipartite graphs for each single cell.

Diagram 1: MPX experimental workflow for spatial proteomics.

Data Processing and Spatial Analysis

Following sequencing, the MPX data processing pipeline transforms raw sequence reads into spatial proteomics networks [6]:

- Read Processing and UMI Counting: Demultiplex sequences and group reads by unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to identify unique AOC molecules.

- Graph Construction: Represent each sequenced unique molecule as an edge in a bipartite graph, with UPI-A and UPI-B sequences as nodes and protein identity as edge attributes.

- Single-Cell Separation: Separate graph components into distinct graphs corresponding to single cells based on connectivity patterns.

- Spatial Analysis: Calculate spatial statistics on graph representations:

- Polarity Score: Derived from Moran's I autocorrelation statistic to measure clustering or nonrandomness of a protein's spatial distribution. Positive scores indicate clustering, scores near zero indicate random distribution.

- Colocalization Analysis: Assess pairwise spatial relationships between different proteins to identify potential interactions or coordinated organization.

- Cell Type Annotation: Process protein count matrices similarly to other single-cell technologies (CLR transformation, Louvain clustering, UMAP visualization) to annotate cellular identities based on surface protein expression.

Diagram 2: MPX computational analysis pipeline from sequencing to spatial insights.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementing spatial proteomics requires specialized reagents and computational tools. The following table details key components for establishing these methodologies in the research laboratory.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Proteomics

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Oligonucleotide Conjugates (AOCs) | Target-specific protein labeling with unique DNA barcodes | Molecular Pixelation for multiplexed surface protein detection [6] [9] |

| DNA Pixels | Nanometer-sized DNA concatemers with unique pixel identifiers (UPIs) | Spatially associating proximate AOCs in MPX workflow [6] |

| Pixelator Pipeline | Open-source computational tool for processing MPX sequencing data | Graph construction and spatial analysis from MPX sequencing data [6] |

| Human Protein Atlas | Public database of protein localization across tissues and cells | Reference for protein localization patterns and validation [32] |

| PUPS Model | AI-based prediction of protein subcellular localization | Predicting location of uncharacterized proteins or in novel cell contexts [31] |

| IntegrAO Tool | Graph neural network for integrating incomplete multi-omics datasets | Patient stratification with partial multi-omics data [33] |

| NMFProfiler Framework | Identifies biologically relevant signatures across omics layers | Biomarker discovery and patient subgroup classification [33] |

| Alanopine | Alanopine, CAS:19149-54-3, MF:C6H11NO4, MW:161.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Alphadolone | Alphadolone, CAS:14107-37-0, MF:C21H32O4, MW:348.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications and Future Directions in Biomedical Research

Advancing Drug Discovery and Development

Spatial proteomics is transforming drug discovery by providing unprecedented insights into drug mechanisms and cellular responses. The ability to map protein organization at single-cell resolution enables researchers to understand how drugs modulate protein interactions, spatial clustering, and signaling complexes. For instance, MPX has been used to study immune cell dynamics by applying spatial statistics to identify known and new patterns of spatial organization of proteins on chemokine-stimulated T cells [6]. In drug-target interaction prediction, novel computational models like GHCDTI use graph neural networks and multi-level contrastive learning to predict drug-target interactions, addressing challenges of data imbalance and incorporating protein dynamic features [35]. These approaches can process 1,512 proteins and 708 drugs in under two minutes, highlighting their potential for scalable virtual screening and drug repositioning [35].

Enhancing Patient Stratification in Clinical Trials

Integrating spatial proteomics with other omics technologies enables more precise patient stratification for oncology clinical trials. Multi-omics approaches provide a comprehensive view of tumor biology, with each layer offering distinct insights: genomics reveals driver mutations, transcriptomics shows pathway activity, and proteomics investigates the functional state of cells [33]. When combined with spatial biology, which preserves tissue architecture, researchers can understand how cells interact and how immune cells infiltrate tumors [33]. This integrated approach allows tumors to be grouped by molecular and immune profiles, enabling precise patient selection in trials and improving the chances of detecting true treatment effects. This is particularly crucial for immunotherapies, where despite promising results, many patients still do not respond due to tumor complexity [33].

Future Technological Convergence

The future of spatial proteomics lies in the convergence of experimental and computational methods, increased multiplexing capabilities, and applications to clinical samples. Emerging trends include:

- Increased Multiplexing: Expanding beyond hundreds to thousands of simultaneously mapped proteins.

- Dynamic Resolution: Capturing temporal changes in protein organization in response to stimuli.

- Multi-Omics Integration: Combining spatial proteomics with spatial transcriptomics and genomics in the same sample.

- AI Enhancement: Using machine learning models, like PUPS, to predict localizations for uncharacterized proteins and cell states [31].

- Clinical Translation: Applying these techniques to formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) clinical specimens for biomarker discovery.

As spatial proteomics technologies continue to evolve and integrate with artificial intelligence, they will undoubtedly uncover new biological mechanisms and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics across a spectrum of human diseases.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications: From MPX Workflows to Clinical Discoveries

Molecular Pixelation (MPX) is an optics-free spatial proteomics method that maps the nanoscale organization of cell surface proteins on single cells using DNA-sequencing. By combining antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates (AOCs) with DNA-based molecular pixels, MPX enables the in-silico reconstruction of protein spatial networks, providing data on protein abundance, clustering, and colocalization for up to 155 targets simultaneously. This technical guide details the MPX workflow, its core components, and analytical output, positioning it as a transformative technology for drug development and basic research in immunology and cell biology [6] [36].

Molecular Pixelation (MPX) addresses a critical gap in spatial proteomics by enabling highly multiplexed, nanoscale mapping of cell surface protein organization without microscopy. Traditional fluorescence microscopy is limited in throughput and multiplexing, typically allowing simultaneous assessment of only about four targets per staining cycle. While super-resolution imaging provides greater detail, it remains constrained by multiplexing capabilities, throughput, and instrumental complexity [6] [37].

MPX overcomes these limitations by using DNA sequence as a proxy for spatial location. The method reveals how the spatial distribution of proteins governs vital immune processes such as intercellular communication, mobility, and signaling—processes fundamental to understanding drug mechanisms, cellular therapy efficacy, and disease pathophysiology [6] [36]. MPX generates single-cell spatial proteomics networks, recording both the abundance and relative spatial arrangement of dozens to hundreds of proteins in a single assay [6].

The MPX Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

The MPX protocol involves a series of biochemical steps performed on fixed cells in suspension, culminating in next-generation sequencing (NGS) and computational graph reconstruction. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow:

Step 1: Cell Fixation and Staining with Antibody-Oligonucleotide Conjugates (AOCs)

The workflow begins with chemical fixation of cells, typically using paraformaldehyde (PFA), to preserve the native spatial organization of cell surface proteins. Fixed cells are then stained with a multiplexed panel of AOCs. Each AOC consists of a monoclonal antibody conjugated to a unique, protein-specific DNA oligonucleotide barcode. This panel can target dozens to over 150 surface proteins simultaneously. For example, published studies have used panels of 76 immune cell surface proteins, while commercial kits are available for 155-plex analysis [6] [36].

Step 2: First DNA Pixel Hybridization and Gap-Fill Ligation

After AOC staining, cells are incubated with the first set of "DNA pixels." These are single-stranded DNA molecules—generated by rolling circle amplification—that form nanometer-sized structures (<100 nm in diameter). Each DNA pixel contains a concatemer of a unique sequence identifier called a Unique Pixel Identifier (UPI-A). These DNA pixels hybridize to multiple spatially proximate AOCs on the cell surface. A subsequent gap-fill ligation reaction covalently incorporates the UPI-A sequence onto the oligonucleotides of the hybridized AOCs. This step effectively defines molecular neighborhoods by tagging groups of AOCs that were near each other on the cell surface with the same UPI-A barcode [6].

Step 3: Enzymatic Degradation of the First DNA Pixel Set

The first set of DNA pixels is enzymatically degraded and washed away. This removal is crucial for enabling the second, independent spatial indexing step that follows, ensuring that the two pixelation events do not interfere with each other [6].

Step 4: Second DNA Pixel Hybridization and Gap-Fill Ligation

A second set of DNA pixels, containing a different unique sequence identifier (UPI-B), is introduced. These pixels hybridize to AOCs and undergo gap-fill ligation, similar to the first step. However, because the UPI-B pixels connect different combinations of AOCs, they create an overlapping but distinct set of neighborhoods. The serial application of two DNA pixel sets with different UPI barcodes (UPI-A and UPI-B) creates a complex network of spatial relationships from which the relative positions of proteins can be computationally reconstructed [6] [37].

Step 5: Library Preparation and Sequencing

Following the two pixelation steps, the cells are lysed, and the tagged AOC oligonucleotides are amplified by PCR to create a sequencing library. The amplicons contain four key pieces of information: (1) a molecular barcode (UMI) identifying unique AOC molecules, (2) the protein identity barcode, (3) the UPI-A barcode, and (4) the UPI-B barcode. The library is then sequenced using standard high-throughput next-generation sequencing platforms [6] [38].

Step 6: Computational Analysis and Graph Reconstruction

The sequencing reads are processed using specialized computational pipelines, such as the open-source Pixelator pipeline or nf-core/pixelator [38]. The data from each cell is represented as a bipartite graph, where UPI-A and UPI-B sequences form one set of nodes, and the AOC molecules (edges) connect them. This graph can be projected for analysis, with A-nodes (from UPI-A) containing the protein identity attributes [6] [37] [39]. Graph components are separated to correspond to individual cells, enabling single-cell analysis of protein abundance and spatial distribution through metrics like polarity scores (spatial autocorrelation) and adjusted local assortativity (colocalization) [6] [37].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The MPX assay relies on several core components, each playing a critical role in generating high-quality spatial proteomics data.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for the MPX Workflow

| Reagent | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Oligonucleotide Conjugates (AOCs) | Bind specifically to target cell surface proteins; encode protein identity via DNA barcode. | Validated for specificity; panel size (e.g., 76-plex to 155-plex); minimal cross-reactivity [6] [36]. |

| DNA Pixels | Define spatial neighborhoods by hybridizing to proximate AOCs. | Nanometer-sized (~100 nm); contain unique pixel identifiers (UPI); generated via Rolling Circle Amplification [6]. |

| Fixation Reagent | Immobilize the cell surface proteome in its native state. | Typically Paraformaldehyde (PFA); preserves protein spatial organization [6] [37]. |

| Gap-Fill Ligation Enzymes | Covalently link UPI sequences from DNA pixels to AOCs. | High efficiency to maximize barcode incorporation and data yield [6]. |

| Sequencing Library Prep Kit | Amplify and prepare the final AOC amplicons for sequencing. | Compatibility with the AOC construct and your NGS platform of choice [38]. |

Data Output and Analytical Capabilities

MPX data provides multi-dimensional insights at the single-cell level, going far beyond simple protein abundance.

Table 2: Quantitative Data and Analytical Metrics from MPX

| Data Type | Description | Representative Value | Analytical Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Abundance | Number of unique AOC molecules (UMIs) per cell for each protein. | Enables cell type identification (e.g., T cells, B cells) and population frequency analysis [6]. | Centered Log Ratio (CLR) transformation; Louvain clustering; UMAP visualization [6]. |

| Spatial Networks | Graph representation of protein neighborhoods for each cell. | >1,000 spatially connected zones (UPI-A) per cell; ~9,500 AOC UMIs per cell [6]. | Graph theory; Bipartite graph analysis; A-node projection [6] [37] [39]. |

| Protein Clustering/Polarity | Measure of non-random, clustered spatial distribution of a single protein. | Polarity score based on Moran's I spatial autocorrelation; detects protein capping/polarization [6]. | Spatial autocorrelation on graph adjacency matrices [6]. |

| Protein Colocalization | Measure of spatial proximity between two or more different proteins. | Identifies protein constellations (e.g., in uropods or after drug treatment) [37] [39]. | Adjusted local assortativity; Jaccard Index; Pearson's correlation [37] [39]. |