Standardizing High-Dimensional Cytometry Data: A Comprehensive Guide from Experimental Design to Clinical Validation

High-dimensional cytometry has revolutionized single-cell analysis, yet its full potential in biomedical research and drug development is hampered by standardization challenges.

Standardizing High-Dimensional Cytometry Data: A Comprehensive Guide from Experimental Design to Clinical Validation

Abstract

High-dimensional cytometry has revolutionized single-cell analysis, yet its full potential in biomedical research and drug development is hampered by standardization challenges. This article provides a comprehensive framework for optimizing high-dimensional cytometry data analysis, addressing critical needs from foundational principles to clinical application. We explore the transition from conventional to spectral cytometry, detail best practices in panel design and computational analysis using tools like cyCONDOR and automated gating, and outline robust quality control procedures for multicenter studies. Furthermore, we examine validation strategies essential for clinical translation and compare emerging technologies shaping the future of the field. This guide equips researchers and drug development professionals with actionable strategies to enhance data reproducibility, analytical depth, and clinical impact.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Technological Shifts in High-Dimensional Cytometry

The advent of technologies capable of measuring over 40 parameters simultaneously at the single-cell level has fundamentally transformed cytometry from a targeted, hypothesis-driven tool to an exploratory discovery platform [1] [2]. This technological revolution, exemplified by mass cytometry (CyTOF) and spectral flow cytometry, has rendered traditional analytical approaches inadequate. Conventional gating, which relies on sequential bivariate plotting, cannot efficiently handle the complexity of high-dimensional data, as the number of possible two-marker combinations increases quadratically with parameter count, creating a "dimensionality explosion" [1]. This paradigm shift requires researchers to move from manual, hierarchical gating to automated, computational approaches that view data as an integrated whole rather than disconnected two-dimensional views [3].

The core challenge lies in the inherent limitations of human pattern recognition in high-dimensional spaces. While immunologists can readily identify populations in two-dimensional plots, this approach becomes not only laborious but potentially biased, as it relies heavily on the investigator's existing knowledge and expectations [1] [2]. Furthermore, manual gating struggles to identify novel or rare cell populations and cannot easily discern complex, multi-marker relationships [1]. This transition necessitates a change in mindset—high-dimensional cytometry is not merely "conventional cytometry with extra spaces" but requires integrated experimental and analytical planning from the outset to fully leverage its discovery potential [2].

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Modern Analytical Approaches

The transition from conventional to high-dimensional analysis represents a fundamental methodological evolution. The table below summarizes the core differences between these approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional Gating and High-Dimensional Clustering

| Feature | Conventional Gating | High-Dimensional Clustering |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Basis | Manual, hypothesis-driven [2] | Automated, data-driven, and unsupervised [1] |

| Primary Workflow | Sequential biaxial plots and hierarchical gating [1] | Computational clustering and dimensionality reduction [4] [1] |

| Dimensionality Handling | Limited by the number of practical 2D plots; suffers from "dimensionality explosion" [1] | Designed specifically to handle 40+ parameters simultaneously [4] [2] |

| Investigator Bias | High (relies on operator judgment and experience) [3] | Low (algorithm-driven, though interpretation remains subjective) [1] |

| Discovery Potential | Limited to pre-defined populations; poor for rare/novel cell detection [2] | High; excels at identifying novel populations and continuous cell states [4] [1] |

| Scalability | Poor; becomes unmanageable with increasing parameters [3] | High; computational power enables analysis of millions of cells [4] |

| Key Tools | FlowJo, FCS Express [3] | cyCONDOR, FlowSOM, SPECTRE, UMAP, t-SNE [4] [1] |

This shift is not merely technical but philosophical. Traditional cytometry often starts with a specific hypothesis about known cell populations, while high-dimensional approaches can begin with an open-ended exploration of cellular heterogeneity, generating new hypotheses from the data itself [2]. This exploratory power makes high-dimensional cytometry instrumental not only in immunology but increasingly in microbiology, virology, and neurobiology [4].

Essential Tools for High-Dimensional Analysis

Successful implementation of a high-dimensional clustering workflow requires a suite of software tools and algorithms, each serving a specific function in the analytical pipeline.

Table 2: Key Analytical Algorithms and Software for High-Dimensional Cytometry

| Tool Category | Example Tools/Algorithms | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated Platforms | cyCONDOR [4], SPECTRE [4], Catalyst [4] | End-to-end analysis ecosystems covering pre-processing to biological interpretation |

| Commercial Platforms | Cytobank, Omiq, Cytolution [4] | Feature-rich tools with intuitive graphical user interfaces (GUIs) |

| Clustering Algorithms | FlowSOM [4], PhenoGraph [4] | Unsupervised identification of cell populations based on marker similarity |

| Non-Linear Dimensionality Reduction | t-SNE [1], UMAP [1], HSNE [1] | Visualization of high-dimensional data in 2D or 3D while preserving structure |

| Trajectory Inference | Diffusion Pseudotime (DPT) [1], PAGA [1] | Inference of continuous cellular differentiation paths from snapshot data |

| Programming Environment | R Statistical Programming Language [3] | Primary environment for implementing most open-source analytical tools |

These tools collectively enable researchers to perform an unbiased dissection of cellular heterogeneity. For instance, cyCONDOR provides a comprehensive toolkit that includes data ingestion, batch correction, clustering, dimensionality reduction, and advanced downstream functions like pseudotime analysis and machine learning-based classification, all within a unified data structure designed for non-computational biologists [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My data has always been sufficient with manual gating. Why should I switch to a more complex high-dimensional workflow? High-dimensional clustering is essential when your research question involves discovering novel cell populations, understanding complex cellular heterogeneity, or analyzing more than 15-20 parameters simultaneously [2]. Manual gating becomes statistically unreliable and practically unmanageable in these scenarios due to the "dimensionality explosion," where the number of required two-dimensional plots increases quadratically [1]. High-dimensional clustering provides an unbiased, comprehensive view of your entire dataset, revealing populations and relationships that would be impossible to find manually [3].

Q2: How do I know if my clustering results are biologically real and not computational artifacts? Robust clustering requires multiple approaches. First, validate that identified clusters are stable across different algorithms (e.g., compare FlowSOM and PhenoGraph) [4]. Second, biologically meaningful clusters should be reproducible across biological replicates. Third, use visualization techniques like t-SNE or UMAP to confirm that clusters form distinct groupings in dimensional reduction space [1]. Finally, always relate computational findings back to biological knowledge—clusters should represent populations that are biologically plausible [2].

Q3: What are the most common pitfalls in transitioning to high-dimensional data analysis? The most significant pitfalls include: (1) Poorly defined research questions leading to inclusion of irrelevant markers that increase noise [2]; (2) Attempting to analyze data without basic biological pre-gating to remove debris and doublets, which increases computational load and can obscure real signals [4]; (3) Treating high-dimensional analysis as a black box and failing to critically interpret algorithm outputs [5]; (4) Neglecting batch effects that can create technical, rather than biological, clusters [4].

Q4: Can I integrate high-dimensional clustering with my existing manual gating strategies? Absolutely. In fact, an integrated approach is often most powerful. You can use manual gating for initial quality control and to remove debris/dead cells/doublets before high-dimensional analysis [4]. Conversely, you can use clustering to identify populations of interest and then export these populations back to conventional flow cytometry software for further visualization and validation. Many tools, including cyCONDOR, offer workflows for importing FlowJo workspaces to facilitate comparison between cluster-based and conventional gating-based cell annotation [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Challenges

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common High-Dimensional Analysis Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Over-clustering (too many small clusters) | Algorithm parameters (e.g., k-value) set too high; over-interpretation of technical noise. | Reduce the number of clusters (k); merge similar clusters post-analysis; validate small clusters across replicates. |

| Under-clustering (too few, heterogeneous clusters) | Algorithm parameters set too low; excessive downsampling. | Increase the number of clusters (k); ensure sufficient cell numbers for analysis; use hierarchical clustering approaches. |

| Poor separation in UMAP/t-SNE plots | Incorrect perplexity parameter (t-SNE); too few cells analyzed; excessive technical variation. | Adjust perplexity (typically 5-50 for t-SNE) [1]; ensure adequate cell input; apply batch correction algorithms [4]. |

| Clusters dominated by batch effects | Sample processing variability; instrument performance drift between runs. | Implement batch correction tools (available in cyCONDOR) [4]; use biological reference samples for standardization [6]; include control samples in each batch. |

| Weak or No Signal in Key Markers | Inadequate fixation/permeabilization; suboptimal antibody titration; poor panel design. | Optimize fixation/permeabilization protocols [7]; titrate all antibodies; use brightest fluorochromes for low-density targets [7]. |

| High Background/Non-specific Staining | Fc receptor binding; antibody concentration too high; dead cells included. | Use Fc receptor blocking; titrate antibodies to optimal concentration [7]; include viability dye to exclude dead cells [7]. |

| Inability to Reproduce Findings | Stochastic nature of some algorithms; inadequate computational resources for full dataset. | Set random seeds for reproducible results; ensure sufficient computational resources or use scalable tools like cyCONDOR [4]. |

Experimental Protocol: Standardized Workflow for High-Dimensional Analysis

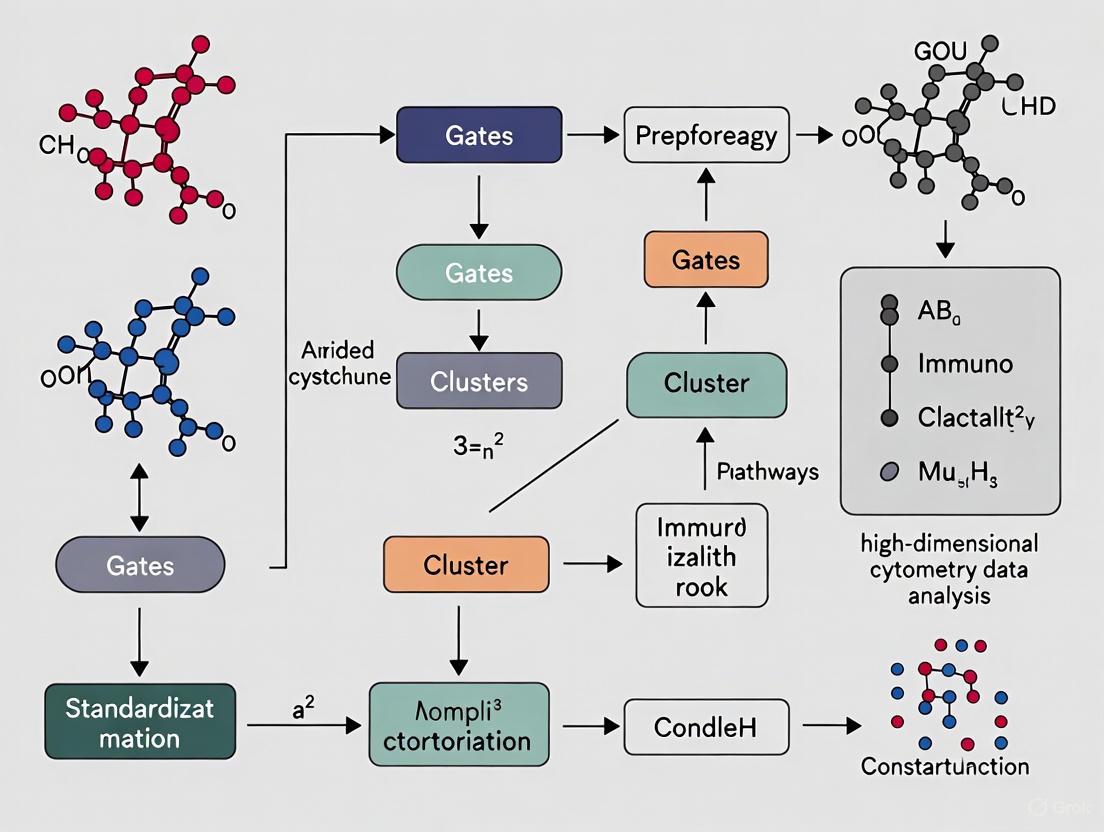

A robust, standardized analytical workflow is crucial for generating meaningful, reproducible results from high-dimensional cytometry data. The following diagram illustrates the key stages of this process:

Detailed Protocol Steps

Experimental Design and Panel Design: Begin with a clearly defined research question to guide marker selection and avoid inclusion of irrelevant parameters that add noise [2]. Incorporate biological knowledge to establish preliminary gating strategies for major cell lineages.

Data Acquisition and Standardization: To minimize technical variation between runs, use calibration beads or biological reference samples to establish and maintain target fluorescence intensities across detectors [6]. Note that this will not eliminate batch effects from sample preparation and staining [6].

Data Pre-processing:

- Data Transformation: Apply appropriate transformations (e.g., arcsinh for CyTOF, logicle for flow cytometry) to ensure proper distribution for downstream analysis [4].

- Quality Control: Perform basic gating prior to high-dimensional analysis to exclude debris, doublets, and dead cells, thereby reducing computational demands [4].

- Batch Correction: Apply algorithms to correct for technical variation between experimental batches when present [4].

Dimensionality Reduction: Use non-linear techniques like UMAP or t-SNE for visualization. UMAP is generally preferred as it better preserves global data structure and scales efficiently to large datasets [1]. For t-SNE, use appropriate perplexity values (typically 5-50) and run multiple iterations due to its stochastic nature [1].

Clustering and Population Identification: Apply unsupervised clustering algorithms such as FlowSOM or PhenoGraph to identify cell populations based on marker expression similarity. cyCONDOR implements multi-core computing for PhenoGraph to improve runtime with large datasets [4].

Biological Interpretation: Analyze cluster characteristics through marker expression patterns and relate findings to existing biological knowledge. Use pseudotime analysis tools like Diffusion Pseudotime (DPT) to investigate cellular differentiation trajectories [1].

Validation and Hypothesis Testing: Validate findings through cross-replication with independent samples or complementary methodologies. Many high-dimensional experiments serve as hypothesis-generating, with subsequent targeted experiments designed for validation [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful high-dimensional cytometry relies on carefully selected and validated reagents. The following table outlines essential materials and their functions:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for High-Dimensional Cytometry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Calibration Beads | Instrument performance standardization and tracking [6] | Use to establish target fluorescence values and adjust PMT voltages in subsequent runs to minimize day-to-day instrument variation [6] |

| Biological Reference Samples | Batch effect assessment and normalization [6] | Frozen PBMC pools from healthy donors provide a biological control for sample preparation and staining variability |

| Viability Dyes | Exclusion of dead cells from analysis [7] | Use fixable viability dyes for intracellular staining; these withstand fixation and permeabilization steps |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent | Reduction of non-specific antibody binding [7] | Critical for minimizing background staining, particularly in myeloid cells that express high Fc receptor levels |

| Bright Fluorochrome Conjugates | Detection of low-abundance targets [7] | Pair the brightest fluorochromes (e.g., PE) with the lowest density targets (e.g., CD25) for optimal detection |

| Validated Antibody Panels | Specific detection of cellular markers | Pre-test all antibodies in the panel combination; titrate for optimal signal-to-noise ratio [7] |

| Fixation/Permeabilization Kits | Cell structure preservation and intracellular target access [7] | Optimization required for different targets; formaldehyde with saponin, Triton X-100, or methanol for different applications |

Advanced Analytical Pathways

Beyond basic clustering and visualization, high-dimensional cytometry enables sophisticated analytical approaches that extract deeper biological insights from complex datasets. The following diagram illustrates these advanced analytical pathways:

Implementation of Advanced Analytics

Machine Learning Classification: Tools like cyCONDOR incorporate deep learning algorithms for automated annotation of new datasets and classification of samples based on clinical characteristics [4]. This facilitates the transition from exploratory analysis to clinically applicable diagnostic tools.

Pseudotime Analysis: Originally developed for single-cell RNA sequencing data, trajectory inference algorithms like Diffusion Pseudotime (DPT) can be applied to cytometry data to reconstruct continuous biological processes, such as cellular differentiation or activation pathways, from static snapshot data [1].

Differential Abundance Testing: Statistical comparison of cell population frequencies between experimental conditions or clinical groups provides crucial biological insights. This approach can identify populations associated with disease states or treatment responses [4].

Batch Effect Integration: As multi-center and longitudinal studies become more common, batch integration tools are essential for combining datasets without introducing technical artifacts. cyCONDOR provides built-in functionality for this purpose [4].

The paradigm shift from conventional gating to high-dimensional clustering represents more than a technical upgrade—it constitutes a fundamental transformation in how we design experiments, analyze data, and generate biological insights. By embracing standardized workflows, appropriate troubleshooting strategies, and advanced analytical pathways, researchers can fully leverage the power of high-dimensional cytometry to unravel complex biological systems and accelerate discovery.

The following table summarizes the core technological differences between spectral flow cytometry and mass cytometry.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Spectral Flow Cytometry and Mass Cytometry

| Feature | Spectral Flow Cytometry | Mass Cytometry (CyTOF) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Fluorescence-based detection using conventional lasers [8] | Mass spectrometry-based detection using metal isotopes [9] [10] |

| Detection System | Array of detectors (e.g., PMTs) to capture full emission spectrum (350-850 nm) [11] [8] | Time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer to detect atomic mass tags [10] |

| Key Reagents | Antibodies conjugated to fluorochromes (e.g., Brilliant Violet, Spark dyes) [11] | Antibodies conjugated to heavy metal isotopes (e.g., lanthanides) [9] [10] |

| Signal Resolution | Spectral unmixing of overlapping emission spectra [8] [12] | Distinction of isotopes by mass-to-charge ratio with minimal overlap [10] |

| Primary Limitation | Spectral overlap can complicate panel design [11] [12] | Lower throughput; cannot perform cell sorting; destroys samples [11] [10] |

| Typical Max Parameters | 40+ colors from a single tube [12] [13] | 40+ parameters simultaneously [9] [10] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: How do I choose between spectral flow cytometry and mass cytometry for my high-dimensional panel?

Answer: The choice depends on your experimental goals, sample type, and required throughput. Consider the following criteria:

Choose Spectral Flow Cytometry if:

- Your research requires high-speed cell sorting for downstream functional assays, as it is compatible with cell sorters [11].

- You are working with live cells and need to maintain cell viability.

- Your laboratory already has expertise in fluorescent panel design, and you wish to leverage existing knowledge and reagent investments [8].

- Your experimental design demands very high acquisition speeds (e.g., >10,000 cells/second) [11].

Choose Mass Cytometry if:

- Your panel requires the absolute maximum number of parameters with minimal signal interference, as metal tags have virtually no overlap [9] [10].

- You are working with highly autofluorescent samples (e.g., tumor digests, yeast, fibroblasts), as mass cytometry is not affected by autofluorescence [9].

- Your workflow involves fixed samples, batch analysis, or archiving, as metal tags are highly stable and not susceptible to degradation [9].

- You need to deeply characterize intracellular markers, such as phosphoproteins, transcription factors, and cytokines, without signal quenching from physical cell barriers [9].

FAQ 2: My spectral cytometry data shows poor resolution between cell populations. What are the primary causes and solutions?

Answer: Poor resolution in spectral cytometry often stems from suboptimal panel design or improper handling of autofluorescence.

Cause: Incorrect Fluorochrome Assignment.

- Solution: Adhere to the "Brightness to Antigen Density" rule. Match the brightest fluorochromes (e.g., Brilliant Violet series) to low-abundance markers and dimmer fluorochromes to highly expressed antigens [8] [12]. Use the instrument's spectrum viewer tool to select fluorochromes with distinct full spectral signatures, not just different peak emissions [8].

Cause: Unaccounted Autofluorescence.

Cause: Inadequate Single-Stained Controls.

- Solution: For accurate spectral unmixing, you must generate a reference spectrum for every fluorochrome in your panel using high-quality, properly titrated single-stained controls. The purity of these controls is critical for building an accurate unmixing matrix [12].

FAQ 3: I am detecting high background noise in my mass cytometry data. How can I mitigate this?

Answer: Background noise in mass cytometry (CyTOF) is often related to oxide formation or contamination.

Cause: Metal Oxide Formation.

- Solution: Oxides of lanthanide metals can form during the ionization process, creating signals in adjacent mass channels. To minimize this, ensure the instrument's quadrupole is properly tuned to remove low-mass contaminants and regularly maintain the instrument to optimize plasma conditions [10]. Panel design software (e.g., Maxpar Panel Designer) can help you avoid assigning markers to channels prone to oxide interference.

Cause: Environmental Contamination.

- Solution: Use high-purity reagents and ensure your sample preparation area is free from heavy metal contamination. Incorporate a cell barcoding strategy, where samples are labeled with unique combinations of metal barcodes before pooling. This allows for sample multiplexing, minimizes inter-sample variation, and reduces the potential for contamination during acquisition [9] [10].

Cause: Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio.

- Solution: Ensure antibodies are titrated correctly for mass cytometry. Using an antibody concentration that is too high can increase non-specific binding and background, while a concentration that is too low will yield a weak signal [10].

Experimental Protocols for Standardization

Protocol: Validating a High-Dimensional Spectral Flow Cytometry Panel for Clinical Immune Profiling

This protocol is designed for standardizing deep immunophenotyping of human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) using a spectral flow cytometer capable of 28+ colors.

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Antibody Panel: Pre-formulate a master mix of titrated, fluorescently-conjugated antibodies against your target markers (e.g., CD45, CD3, CD19, CD4, CD8, CD56, CD14, CD16, CCR7, CD45RA, etc.) [12].

- Staining Buffer: Use PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.1% sodium azide.

- Viability Stain: Incorporate a fixable viability dye (e.g., Zombie NIR) to exclude dead cells.

- Reference Controls: Prepare single-stained compensation beads and unstained cells for each fluorochrome used.

2. Staining Procedure: 1. Cell Preparation: Resuspend up to 10^7 PBMCs in staining buffer. 2. Fc Receptor Blocking: Incubate cells with an Fc receptor blocking agent for 10 minutes on ice. 3. Viability Staining: Stain cells with the viability dye for 15 minutes at room temperature, protected from light. 4. Surface Staining: Wash cells and incubate with the pre-mixed antibody cocktail for 30 minutes at 4°C in the dark. 5. Wash and Fix: Wash cells twice with staining buffer and resuspend in a fixation buffer (e.g., 1-2% formaldehyde). 6. Data Acquisition: Run samples on the spectral flow cytometer according to manufacturer's instructions, ensuring instrument QC has been performed.

3. Data Acquisition and Unmixing:

- Acquire single-stained controls to create a reference spectral library.

- Acquire experimental samples. The instrument's software (e.g., SpectroFlo) will use this library to perform linear unmixing, separating the contribution of each fluorochrome and autofluorescence to the final signal [8] [13].

Protocol: Standardized Immune Profiling of PBMCs using Mass Cytometry

This protocol outlines a standardized workflow for a 30+ parameter immunophenotyping panel on a CyTOF system.

1. Reagent and Sample Preparation:

- Antibody Panel: Use a pre-validated, metal-tagged antibody panel (e.g., Maxpar Direct Immune Profiling Assay or a custom panel) [9].

- Cell Barcoding: Label individual samples with a unique combination of palladium (Pd) barcoding tags. Pool all barcoded samples into a single tube to minimize staining variability and acquisition time [10].

- Staining Buffer: Use Maxpar Cell Staining Buffer.

2. Staining and Data Acquisition: 1. Cell Staining: Incubate the pooled, barcoded cell sample with the surface antibody cocktail for 30 minutes at room temperature. 2. Fixation and Intercalation: Wash cells and fix with a formaldehyde-containing fixative. For DNA staining, permeabilize cells and incubate with an iridium (Ir) intercalator to label nucleic acids. 3. Data Acquisition: Resuspend cells in water containing EQ normalization beads. Acquire data on the CyTOF instrument. The normalization beads allow for signal standardization over time [9].

3. Post-Acquisition Data Analysis:

- Debarcoding: Use the instrument's software to identify the barcode signature for each cell event and assign it back to its original sample.

- Clustering and Dimensionality Reduction: Process the FCS files through an analysis pipeline (e.g., cyCONDOR) for normalization, clustering (e.g., Phenograph, FlowSOM), and visualization using t-SNE or UMAP [4].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow and signal detection pathways for both technologies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Resources for High-Dimensional Cytometry

| Category | Item | Function & Importance in Standardization |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Flow Cytometry | Brilliant Violet, Spark PLUS Dyes | Bright, photostable fluorochromes essential for expanding panel size and detecting low-abundance markers [11]. |

| Single-Stained Control Particles | Critical for generating the reference spectral library required for accurate unmixing of multicolor panels [8]. | |

| Fixable Viability Dyes | Allows exclusion of dead cells, which non-specifically bind antibodies and increase background fluorescence. | |

| Mass Cytometry | Maxpar Metal-Labeled Antibodies | Antibodies pre-conjugated to pure lanthanide isotopes, ensuring consistent performance and simplifying panel design [9]. |

| Cell ID Palladium Barcoding Kit | Enables multiplexing of up to 20 samples, reducing acquisition time and technical variability [9] [10]. | |

| Iridium Intercalator | A nucleic acid intercalator used as a stable DNA stain for identifying nucleated cells and normalizing for cell size [10]. | |

| Data Analysis | cyCONDOR, Cytobank, Omiq | Integrated software platforms providing end-to-end analysis workflows (clustering, dimensionality reduction) for high-dimensional data, crucial for standardized interpretation [4]. |

| Normalization Beads | (e.g., EQ Beads for CyTOF) Used to monitor and correct for instrument sensitivity drift over time, ensuring data quality and reproducibility [9]. |

Defining Clear Research Questions to Guide Panel Design and Analysis Strategy

Technical Support Center

FAQs: Formulating Your Research Question

What makes a good research question in the context of high-dimensional cytometry? A well-constructed research question is the foundation of a successful cytometry experiment. It should be [14]:

- Clear and focused, explicitly stating what the research needs to accomplish.

- Not too broad and not too narrow, ensuring the scope is appropriate for a thorough investigation.

- Analytical rather than descriptive, moving beyond "what" to explore "how," "why," or "what is the effect." [14]

- Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant (FINER). This set of criteria helps ensure your question is practical, advances the field, and is worthwhile to pursue. [15]

How can a structured framework help me define my research question? Using a framework ensures you contemplate all relevant domains of your project upfront. The PICO framework is a common and effective choice for experimental designs [15] [16]:

- Population: The specific cell types or subject of your research.

- Intervention: The exposure, treatment, or process you are studying.

- Comparison: The alternative against which the intervention is measured (e.g., a control group).

- Outcome: The effect you are evaluating, which could be a cell population frequency, marker expression level, or clinical outcome.

Table: Adapting the PICO Framework for Cytometry Research

| PICO Component | Definition | Cytometry Example |

|---|---|---|

| Population | The subject(s) of interest | Human CD4+ T-cells from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) |

| Intervention | The action/exposure being studied | Treatment with immunomodulatory drug X |

| Comparison | The alternative action/exposure | Vehicle-treated control (e.g., DMSO) |

| Outcome | The effect being evaluated | Change in the frequency of regulatory T-cell (Treg) subsets, defined as CD4+ CD25+ CD127lo FoxP3+ |

For other study types, alternative frameworks may be more suitable, such as SPICE (Setting, Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, Evaluation) for service evaluations or qualitative studies. [16]

What is the difference between a research question and a hypothesis? A research question specifically states the purpose of your study in the form of a question you aim to answer. A hypothesis is a testable statement that makes a prediction about what you expect to happen [17].

- Research Question: "Is there a significant positive relationship between the weekly amount of time spent outdoors and self-reported levels of satisfaction with life?"

- Alternative Hypothesis (H1): "There is a significant positive relationship between the weekly amount of time spent outdoors and self-reported levels of satisfaction with life."

- Null Hypothesis (H0): "There is no relationship between the weekly amount of time spent outdoors and self-reported levels of satisfaction with life." [17]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: My cytometry data is messy, and I cannot clearly answer my research question.

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Panel Design | Incompatible probe combinations or low-density markers labeled with dim fluorochromes. | Design panels with bright fluorochromes (e.g., PE) for low-density targets (e.g., CD25) and dimmer fluorochromes (e.g., FITC) for high-density targets (e.g., CD8). Use panel design tools and seek expert advice. [18] [19] |

| Weak/No Signal | Inadequate fixation/permeabilization for intracellular targets. | For intracellular targets, ensure appropriate fixation/permeabilization protocols. Formaldehyde fixation followed by permeabilization with Saponin, Triton X-100, or ice-cold methanol is often required. [18] |

| High Background | Non-specific antibody binding or presence of dead cells. | Block cells with Bovine Serum Albumin or Fc receptor blocking reagents. Use a viability dye to gate out dead cells, which non-specifically bind antibodies and are highly autofluorescent. [18] [19] |

| Unresolvable Cell Populations | Incorrect instrument settings or poor sample preparation. | Perform daily quality control on your instrument. Ensure you have a single-cell suspension by filtering samples immediately prior to acquisition to remove clumps and debris. [19] |

Problem: I am struggling with the computational analysis of my multi-sample cytometry data.

A key challenge is comparing corresponding cell populations across multiple samples. A recommended methodology is using a Multi-Sample Gaussian Mixture Model (MSGMM). This approach fits a joint model to multiple samples simultaneously, which [20]:

- Keeps model component parameters (e.g., mean and covariance) fixed across samples but allows mixing proportions (weights) to vary.

- Enhances the detection of rare cell populations by aggregating cells across multiple samples.

- Facilitates direct comparison and consistent labeling of cell clusters across samples.

Diagram: Workflow for Multi-Sample Data Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cytometry

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Viability Dyes (e.g., PI, 7-AAD, Fixable Viability Dyes) | Critical for distinguishing and gating out dead cells, which exhibit high autofluorescence and non-specific antibody binding, thereby improving data quality. [19] |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagents | Used to block non-specific binding of antibodies to Fc receptors on cells like monocytes, reducing background staining. [18] |

| Single-Color Compensation Controls | Essential for multicolor analysis. These are controls (cells or antibody capture beads) used to measure and correct for spectral overlap between fluorescent channels. [19] |

| Fluorescence-Minus-One (FMO) Controls | Experimental controls where all antibodies in a panel are present except one. They are crucial for accurately setting gates, especially for dim and co-expressed markers. [19] |

| Fixation and Permeabilization Buffers | Required for intracellular (e.g., cytokines, transcription factors) or intranuclear staining. Protocols must be optimized for the target and paired with surface staining. [18] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the main technological drivers behind high-dimensional cytometry? High-dimensional cytometry is primarily driven by several advanced technologies that enable the simultaneous measurement of dozens of parameters at the single-cell level. The key technologies include high-dimensional flow cytometry (HDFC), spectral flow cytometry (SFC), mass cytometry (CyTOF), and proteogenomics (CITE-seq/Ab-seq) [4]. Spectral flow cytometry, for instance, uses multiple detectors to capture the entire fluorescence emission spectrum for each fluorochrome, allowing for more precise signal unmixing and the analysis of a greater number of parameters in a single tube compared to conventional flow cytometry [12].

2. What are the most common data analysis challenges? Researchers face significant challenges in managing and interpreting the complex data generated. These include the unsustainability of manual gating for high-dimensional data, which is slow, variable between analysts, and costly [21]. There is also a recognized gap in analytical methods capable of taking full advantage of this complexity, with many existing tools being either limited in scalability or designed for computational experts [4].

3. How is high-dimensional data analysis being standardized and simplified? New integrated computational frameworks are being developed to bridge the data analysis gap. Tools like cyCONDOR provide an end-to-end ecosystem in R that covers essential steps from data pre-processing and clustering to dimensionality reduction and machine learning-based interpretation, making advanced analysis more accessible to wet-lab scientists [4]. Furthermore, commercial software solutions are incorporating automated gating and clustering tools to offer rapid, robust, and reproducible analysis pipelines [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal [22] | Low antigen expression; Inadequate fixation/permeabilization; Dim fluorochrome paired with low-density target. | Optimize treatment to induce target expression; Validate fixation/permeabilization protocol; Pair brightest fluorochrome (e.g., PE) with lowest-density target. |

| High Background [22] [23] | Non-specific antibody binding; Presence of dead cells; High autofluorescence; Incomplete washing. | Include Fc receptor blocking step; Use viability dye to gate out dead cells; Use fluorophores in red-shifted channels (e.g., APC); Increase wash steps. |

| Unusual Scatter Properties [23] | Poor sample quality; Cellular debris; Contamination. | Handle samples with care to avoid damage; Use proper aseptic technique; Avoid harsh vortexing or excessive freeze-thawing. |

| High Data Variability [21] | Subjective manual gating. | Implement automated, algorithm-driven gating tools (e.g., FlowSOM, Phenograph) for more objective and reproducible population identification [4] [21]. |

| Massive Data Volumes [21] | High-throughput experiments with many parameters and samples. | Utilize scalable computational frameworks and cloud-based analysis platforms designed to handle millions of cells [4] [21]. |

Data Analysis Challenges

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Difficulty Visualizing High-Dimensional Data | Data complexity exceeds 2D manual gating. | Employ dimensionality reduction tools like t-SNE, UMAP, or PCA to visualize complex data in 2D plots [21]. |

| Inconsistent Cell Population Identification | Reliance on manual, sequential gating. | Use unsupervised clustering algorithms (e.g., FlowSOM, Phenograph) to identify cell populations in an unbiased manner [4] [21]. |

| Integrating Data from Multiple Batches/Runs | Technical variance between experiments. | Apply batch correction algorithms within analysis pipelines to integrate data for combined analysis [4]. |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Workflow for High-Dimensional Biomarker Discovery

The following diagram illustrates a standardized, end-to-end workflow for discovering biomarkers from high-dimensional cytometry data, integrating both experimental and computational steps.

Protocol 1: Immune Profiling of PBMCs using Mass Cytometry

This protocol is adapted from methodologies featured in presentations and posters at scientific conferences like CYTO 2025 [24].

- Sample Preparation: Isolate fresh Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) from whole blood using density gradient centrifugation. Using fresh cells is recommended over frozen samples for optimal results [22].

- Cell Staining:

- Resuspend cell pellet in a viability staining solution (e.g., a cisplatin-based viability dye) to identify and later exclude dead cells.

- Incubate with Fc receptor blocking reagent to minimize non-specific antibody binding.

- Stain with a surface antibody panel conjugated to metal isotopes. Titrate antibodies beforehand to determine optimal concentrations.

- Fix cells using methanol-free formaldehyde to preserve epitopes [22].

- For intracellular targets, permeabilize cells using ice-cold methanol, adding it drop-wise while vortexing to ensure homogeneous permeabilization and prevent hypotonic shock [22].

- Stain with intracellular antibodies.

- Data Acquisition: Resuspend cells in an appropriate intercalator solution (e.g., Cell-ID Intercalator-Ir) to label DNA. Acquire data on a mass cytometer (CyTOF) following manufacturer's guidelines.

- Data Pre-processing: Normalize data using the manufacturer's normalization algorithm to correct for signal drift over time.

Protocol 2: Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Detection via Spectral Flow Cytometry

This protocol summarizes the application of high-parameter SFC in clinical diagnostics for detecting MRD in hematologic malignancies [12].

- Panel Design: Design a single-tube assay incorporating lineage markers (e.g., CD45, CD19, CD3, CD14) and disease-specific markers (e.g., CD34 for AML, CD19/CD22 for B-ALL). SFC's high multiplexing capacity allows consolidation of markers typically split across multiple tubes into one [12].

- Sample Handling: Process bone marrow aspirates or peripheral blood samples with low cell counts. SFC is particularly suited for low-volume and cryopreserved specimens [12].

- Staining and Acquisition: Follow a standardized staining protocol. Acquire data on a spectral flow cytometer, collecting a high number of events (e.g., 5-10 million) to achieve the required sensitivity for detecting rare malignant clones.

- Data Analysis:

- Use automated clustering algorithms to identify all major cell populations in an unbiased manner.

- Apply a standardized gating hierarchy to identify and quantify the MRD population based on aberrant antigen expression patterns. Sensitivities below 0.01% (10⁻⁴) to as low as 0.001% (10⁻⁵) can be achieved [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Mass Cytometry (CyTOF) [24] [4] | Allows simultaneous detection of over 40 parameters using metal-tagged antibodies, avoiding spectral overlap issues of fluorescent dyes. |

| Spectral Flow Cytometer [12] | Captures full emission spectra of fluorochromes, enabling high-precision unmixing of signals from over 30 markers in a single tube. |

| Viability Dyes (e.g., Cisplatin, 7-AAD) [22] [23] | Critical for identifying and gating out dead cells during analysis, which reduces background and false-positive signals. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent [22] [23] | Minimizes non-specific antibody binding, thereby lowering background staining and improving signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Fixation/Permeabilization Kits [22] | Enable robust detection of intracellular proteins, transcription factors, and phospho-proteins (e.g., for signaling studies). |

| cyCONDOR R Package [4] | An integrated, end-to-end computational framework for analyzing HDC data, from pre-processing to advanced downstream analysis like pseudotime inference. |

| Automated Gating Software (e.g., OMIQ) [21] | Bridges classical gating with cloud-based machine learning workflows, enabling robust, reproducible, and high-throughput cell population identification. |

| Network-Based SVM Models (e.g., CNet-SVM) [25] | A machine learning tool for biomarker discovery that identifies connected networks of genes, providing more biologically relevant biomarkers than isolated gene lists. |

From Data to Discovery: Best Practices in Panel Design, Computational Analysis, and Multi-Omic Integration

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the key factors to balance when designing a high-parameter flow cytometry panel? Designing a high-parameter panel requires a careful balance of several factors to ensure clear resolution of all cell populations. The essential considerations are the instrument configuration (lasers and detectors), the biology of your samples (specifically, the expression level and co-expression patterns of your target antigens), and the properties of your fluorescent dyes (their relative brightness and the degree of spectral overlap, or "spillover") [26]. The core principle for a successful design is to pair a bright fluorochrome with a low-density (dim) antigen, and a dim fluorochrome with a high-density (bright) antigen [26].

2. How can I improve the detection of weakly expressed antigens? Detecting weak antigens (those with as few as 100 fluorescent molecules per cell) is challenging. A patented methodological approach involves:

- Adjusting Instrument Resolution: Set the resolution of the fluorescence channel you are using to 256 (as opposed to the more common 1024) [27].

- Using a Novel Statistical Metric: Calculate the Geometric Mean Fluorescence Intensity Rate (Geo Mean Rate). This is the geometric mean fluorescence intensity of your antigen divided by the geometric mean fluorescence intensity of the cell's Forward Scatter (FS) [27].

- Objective Threshold for Positivity: A sample is considered positive for the weak antigen if its Geo Mean Rate is more than 0.1 higher than the Geo Mean Rate of the isotype or negative control [27]. This method enhances accuracy and reduces subjective judgment.

3. My multicolor panel worked, but the data is messy with high spreading error. What went wrong? High spreading error, which reduces population resolution, is often a consequence of spectral spillover combined with antigen co-expression [26]. If two antigens that are co-expressed on the same cells are labeled with fluorochromes that have significant spectral overlap, the spillover signal can spread the data, making distinct populations hard to distinguish. To fix this, reassign your fluorochromes to avoid pairing dyes with high spillover on co-expressed markers. Utilize tools like fluorescence resolution sorters and spectrum viewers during your panel design to minimize this issue [26].

4. How do I standardize fluorescence intensity across multiple experimental batches? Signal drift between batches is a common challenge. You can standardize data in analysis software like FlowJo using several methods [28]:

- Use a Reference Sample: Designate one well-characterized sample as a reference and scale all other samples to it using batch processing tools.

- Peak Alignment: Use the "Normalize to Mode" function to align the peaks of fluorescence intensity distributions across samples.

- Statistical Normalization: Apply a Z-score normalization plugin to transform data into a standard distribution.

- Instrument Calibration: Regularly run standardized calibration beads (e.g., Rainbow beads) and use the "Bead Normalization" tool to correct for instrument drift over time [28].

5. What are the advantages of computational analysis for high-parameter data? Traditional manual gating becomes subjective and inefficient when analyzing 20+ parameters. Computational approaches offer powerful alternatives [29] [30]:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Algorithms like t-SNE and UMAP project high-dimensional data into 2D or 3D maps, allowing you to visualize complex cell populations and relationships that are impossible to see with traditional plots [29].

- Unsupervised Clustering: Tools like FlowSOM and PhenoGraph automatically identify and group cells with similar marker expression profiles, revealing novel or unexpected cell subsets without prior bias [29]. These methods provide a more objective and comprehensive view of your data's underlying structure.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Resolution of Dim Cell Populations

Potential Cause 1: Mismatched fluorochrome brightness and antigen density. A dim fluorochrome paired with a low-expression antigen will yield a signal too weak to distinguish from background.

- Solution:

- Re-assign Fluorochromes: Consult a fluorochrome brightness table and assign the brightest dyes you have available to your least abundant antigens [26].

- Verify Panel Balance: Use the table below as a guide for pairing.

Potential Cause 2: Excessive spectral spillover from a bright fluorochrome on a co-expressed marker. The bright signal from one channel can spill over and overwhelm the faint signal of your dim population.

- Solution:

- Check Co-expression: Review literature or preliminary data to see if the dim marker is often co-expressed with other markers in your panel.

- Minimize Spillover: If co-expression is likely, avoid labeling the co-expressed marker with a very bright fluorochrome that has significant spillover into the dim marker's detector. Use a dimmer dye or one with less spectral overlap [26].

Problem: High Spreading Error and Inability to Distinguish Populations

Potential Cause: Significant spectral spillover combined with antigen co-expression. [26]

- Solution:

- Analyze Spillover Spreading Matrix: Use your flow cytometry analysis software to calculate a spillover spreading matrix (SSM). This quantitatively shows how much one fluorochrome spreads the signal in every other channel.

- Optimize Fluorochrome Assignment: Identify the largest sources of spreading in your panel and reassign fluorochromes to reduce these critical interactions. The goal is to minimize the highest spillover values, especially for markers that are co-expressed.

- Utilize Panel Design Tools: Leverage software tools that can simulate spillover and help you find an optimal configuration before you order reagents.

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Experimental Batches

Potential Cause: Instrumental drift or variation in sample processing.

- Solution: Implement a Standardization Protocol.

- Pre-Experiment Instrument Calibration: Always run standardized calibration beads before each data acquisition session to monitor laser power and detector sensitivity [28].

- Include Control Samples: In every batch, include a control sample (e.g., a healthy donor PBMC sample) stained with your panel. This serves as a biological reference for signal comparison [28].

- Standardize Analysis: In your analysis software, create and use a template that applies the same gating strategy, axis scaling, and compensation matrices to all data files [28]. Fix the axis ranges on plots to ensure visual consistency.

- Apply Batch Correction: If drift is confirmed, use data normalization functions in your analysis software (e.g., in FlowJo) or statistical methods like ComBat in R to mathematically remove batch effects [28].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Detection of Weak Antigen Expression Using Geo Mean Rate

This protocol is adapted from the patented method in CN102998241A for accurate detection of antigens with low expression levels [27].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a single-cell suspension from your tissue or blood sample. Adjust the concentration to approximately 1x10^6 cells / 100 μL [27].

- Proceed with your standard immunostaining protocol for surface or intracellular antigens.

2. Flow Cytometer Setup:

- Critical Step: Set the resolution of the fluorescence channel used to detect the weak antigen to 256 [27].

- Acquire data from your isotype control or negative control tube first.

- On an FS (Forward Scatter) / Target Fluorescence Channel dot plot, gate on your population of interest.

- Adjust the voltage for the fluorescence channel until the Geometric Mean Fluorescence Intensity (Geo Mean) of the FS is equal to the Geo Mean of the fluorescence channel. At this point, the Geo Mean Rate (Fluorescence Geo Mean / FS Geo Mean) equals 1.0 [27].

3. Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Acquire data from your test sample.

- For both the control and test samples, record the Geo Mean of the target fluorescence channel and the Geo Mean of the FS.

- Calculate the Geo Mean Rate for each sample.

- Interpretation: If the Geo Mean Rate of the test sample is >0.1 higher than the Geo Mean Rate of the control sample, the antigen is considered expressed [27].

Protocol 2: High-Dimensional Data Analysis Using Dimensionality Reduction

This protocol outlines steps for analyzing complex, high-parameter data using computational tools [29].

1. Data Pre-processing and Cleaning:

- Import your FCS data files into an analysis platform (e.g., FlowJo, Cytobank, or R/Python).

- Perform data cleaning by gating out debris (low FSC-A/SSC-A), doublets (excluding events where FSC-H ≠ FSC-A), and dead cells using a viability dye [29].

- Export the pre-processed, single-cell data for downstream analysis.

2. Dimensionality Reduction with UMAP/t-SNE:

- Select all parameters of interest (e.g., all your fluorescence markers) for the analysis.

- Run the UMAP or t-SNE algorithm. It is often helpful to down-sample your data (e.g., to 10,000 cells per file) to reduce computation time [29].

- Visualization: Plot the resulting two-dimensional map. Each point is a single cell, and cells with similar expression profiles will cluster together.

3. Unsupervised Clustering with FlowSOM:

- Run the FlowSOM algorithm on the same set of markers. This will automatically assign each cell to a specific cluster or "metacluster" [29].

- Overlay the FlowSOM cluster identities onto your UMAP/t-SNE plot to visualize the correspondence.

- Analysis: Create heatmaps of the median marker expression for each cluster to interpret their biological identity (e.g., CD4+ T cells, monocytes, etc.).

Table 1: Fluorochrome Brightness Ranking and Pairing Guide

| Fluorochrome | Relative Brightness | Recommended Antigen Density | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE | Very Bright | Low (Tertiary) | High sensitivity but significant spillover. |

| APC | Bright | Low (Tertiary) | Good for dim markers. |

| PE/Cyanine5.5 | Bright | Low to Medium | Check laser compatibility. |

| FITC | Moderate | Medium (Secondary) | Common, but relatively dim. |

| PerCP | Moderate | Medium (Secondary) | Photosensitive; handle with care. |

| Pacific Blue | Dim | High (Primary) | Use for lineage markers. |

| BV421 | Bright | Low (Tertiary) | High laser/filter requirements. |

Table 2: Key Statistical Metrics for Flow Cytometry Data Analysis

| Metric | Use Case | Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Geometric Mean | General fluorescence intensity measurement, especially for skewed distributions [27]. | Less sensitive to extreme outliers than arithmetic mean. |

| Geo Mean Rate | Standardizing intensity for weak antigen detection [27]. | Controls for instrument variation by normalizing to FS. |

| Median | Reporting central tendency for most data. | Robust to outliers. |

| % of Parent | Quantifying population frequency in a gating hierarchy. | Standard for immunophenotyping. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for High-Parameter Flow Cytometry

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Viability Dye | Distinguishes live cells from dead cells to exclude non-specific staining [31]. | Fixable viability dyes (e.g., Zombie dyes) are preferred for fixed samples. |

| Compensation Beads | Used to create single-color controls for accurate calculation of fluorescence compensation [26]. | Anti-mouse/rat/human Igκ beads bind to antibody capture sites. |

| Calibration Beads | Monitor instrument performance and standardize signals across batches [28]. | Rainbow beads with multiple intensity peaks. |

| Collagenase/DNase I | Enzyme mixture for digesting dissected implant or tissue samples into single-cell suspensions [31]. | Concentration and time must be optimized for different tissues. |

| Staining Buffer | The medium for antibody staining steps. | Typically PBS with 1-2% BSA or FBS to block non-specific binding [31]. |

| Fc Receptor Block | Blocks non-specific antibody binding via Fc receptors on cells. | Reduces background staining, critical for myeloid cells. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

High-Parameter Panel Design Workflow

High-Dimensional Data Analysis Pathway

The advent of high-dimensional cytometry technologies, including mass cytometry (CyTOF) and spectral flow cytometry, has revolutionized single-cell analysis, enabling the simultaneous measurement of up to 50 parameters per cell [4] [32]. While these technologies generate rich datasets capable of revealing unprecedented cellular heterogeneity, their full potential can only be unlocked through sophisticated computational tools that move beyond traditional manual gating approaches [4] [33]. This technical support center focuses on three essential tools that form a comprehensive pipeline for unbiased analysis: cyCONDOR, an integrated end-to-end analysis ecosystem; FlowSOM, a self-organizing map-based clustering algorithm; and UMAP, a dimensionality reduction technique for visualization. These tools collectively address the critical need for standardized, reproducible analytical workflows in high-dimensional cytometry, which is paramount for both basic research and clinical translation in immunology, drug development, and biomarker discovery [4] [32] [33]. Framed within the context of cytometry analysis standardization research, this guide provides detailed troubleshooting and experimental protocols to ensure researchers can reliably implement these powerful computational approaches.

Table 1: Core Tool Overview in the High-Dimensional Cytometry Analysis Pipeline

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Algorithm(s) | Data Input | Primary Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cyCONDOR | End-to-end analysis platform | Phenograph, FlowSOM, Harmony, Slingshot | FCS, CSV files, FlowJo workspaces | Annotated clusters, classification models, pseudotime trajectories |

| FlowSOM | Cellular population clustering | Self-Organizing Maps (SOM), Minimal Spanning Tree | Transformed expression matrix | Metaclustered cell populations, star charts |

| UMAP | Dimensionality reduction | Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection | High-dimensional data (e.g., 30+ markers) | 2D/3D visualization embedding |

Tool-Specific Technical Profiles

cyCONDOR: Integrated Analysis Ecosystem

cyCONDOR addresses a critical gap in the computational cytometry landscape by providing a unified R-based framework that encompasses the entire analytical workflow, from data ingestion to biological interpretation [4]. Its development was motivated by the limitations of existing tools that are either web-hosted with limited scalability or designed exclusively for computational biologists, making them inaccessible to wet-lab scientists [4] [34].

Frequently Asked Questions:

Q: What input data formats does cyCONDOR support? A: cyCONDOR accepts standard Flow Cytometry Standard (FCS) files or Comma-Separated Values (CSV) files exported from acquisition software. Additionally, it offers a specialized workflow for importing entire FlowJo workspaces, enabling direct comparison between cluster-based and conventional gating-based annotations [4] [34].

Q: What are the key advantages of cyCONDOR over other available tools? A: Compared to other toolkits, cyCONDOR provides the most comprehensive collection of analysis algorithms within a unified environment. It demonstrates comparable performance to state-of-the-art tools like Catalyst and SPECTRE while requiring fewer functions to perform core analytical steps (4 functions versus 5-9 in other tools) [4]. It also implements multi-core computing for computationally intensive steps like Phenograph clustering, improving runtime efficiency [4].

Q: How does cyCONDOR facilitate analysis in clinically relevant settings? A: The platform includes machine learning algorithms for automated annotation of new datasets and classification of samples based on clinical characteristics. Its scalability to millions of cells while remaining usable on common hardware makes it suitable for clinical applications where sample throughput and reproducibility are paramount [4].

Troubleshooting Guide:

Issue: Difficulty with data transformation parameters. Solution: cyCONDOR provides guided pre-processing with recommended transformation methods for different data types (e.g., different cofactors for MC vs. SFC data). For MC data, use a cofactor of 5 for arcsinh transformation; for SFC data, use a cofactor of 6000 [32].

Issue: High computational demand for large datasets. Solution: Apply basic gating prior to cyCONDOR import to exclude debris and doublets. This pre-filtering significantly reduces computational requirements while maintaining biological relevance [4].

FlowSOM: Clustering Engine

FlowSOM operates as a powerful clustering engine within the high-dimensional analysis pipeline, using self-organizing maps (SOM) to identify cellular subpopulations in an unsupervised manner [33]. The algorithm consists of two main steps: building a self-organizing map of nodes that represent cell phenotypes, followed by consensus meta-clustering to group similar nodes into final populations [33]. This approach efficiently handles large datasets while providing clear visualizations of relationships between clusters through minimal spanning trees.

Frequently Asked Questions:

Q: How does FlowSOM performance compare to other clustering algorithms? A: In comparative studies analyzing the same splenocyte sample by both mass cytometry and spectral flow cytometry, FlowSOM yielded highly comparable results when downsampled to equivalent cell numbers and parameters [32]. The algorithm demonstrates consistent performance across technologies when appropriate data pre-processing is applied.

Q: What input parameters does FlowSOM require? A: A key input requirement for FlowSOM is the exact number of clusters (meta-clusters) the user wants to obtain. This differs from graph-based algorithms like PhenoGraph that use a k-nearest neighbors parameter [33]. The optimal number depends on the biological question, with higher cluster counts resolving rare populations and lower counts identifying major cell lineages.

Troubleshooting Guide:

Issue: Inconsistent clustering results between runs. Solution: Ensure data transformation parameters are standardized across all samples. Set a fixed random seed for reproducibility, as implemented in platforms like CRUSTY which modifies original code to ensure consistent outputs [33].

Issue: Difficulty interpreting FlowSOM clusters biologically. Solution: Use the star charts (radar plots) visualization to examine marker expression patterns for each cluster. Additionally, validate identified populations using expert knowledge and functional assays to establish biological relevance [33].

UMAP: Dimensionality Reduction and Visualization

UMAP has emerged as a powerful dimensionality reduction technique that often preserves more global data structure compared to alternatives like t-SNE [32] [35]. While t-SNE excels at preserving local relationships within clusters, UMAP better maintains the relative positioning between clusters, providing a more accurate representation of the underlying data geometry [35].

Frequently Asked Questions:

Q: Can I cluster directly on UMAP results? A: Yes, but with important caveats. UMAP does not necessarily produce spherical clusters, making K-means a poor choice. Instead, use density-based algorithms like HDBSCAN, which can identify the connected components that UMAP produces [36]. The uniform density assumption in UMAP means it doesn't preserve density well, but it does contract connected components of the manifold together.

Q: Should features be normalized before UMAP? A: For most cytometry applications, yes. Unless features have meaningful relationships with one another (like latitude and longitude), it generally makes sense to put all features on a relatively similar scale using standard pre-processing tools from scikit-learn [36].

Q: How does UMAP compare to PCA and VAEs? A: PCA is a linear transformation suitable for very large datasets as an initial dimensionality reduction step. VAEs are mostly experimental for real-world cytometry datasets. UMAP typically provides the best balance of performance and preservation of data structure for downstream tasks like visualization and clustering [36]. A common pipeline is: high-dimensional embedding → PCA to 50 dimensions → UMAP to 10-20 dimensions → HDBSCAN clustering [36].

Troubleshooting Guide:

Issue: UMAP clusters appear as indistinct blobs without internal structure. Solution: This is often a plotting issue rather than an algorithmic one. Reduce the glyph size in scatter plots (e.g.,

sparameter in matplotlib to 5-0.001) or use specialized plotting libraries like Datashader that better handle large datasets [36].Issue: UMAP runs out of memory with large datasets. Solution: Enable the

low_memory=Trueoption, which switches to a slower but less memory-intensive approach for computing approximate nearest neighbors [36].Issue: Excessive CPU core utilization. Solution: Restrict the number of threads by setting the

NUMBA_NUM_THREADSenvironment variable, particularly useful on shared computing resources [36].

Table 2: Common UMAP Parameters and Troubleshooting Solutions

| Problem | Symptoms | Solution | Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory Exhaustion | Job fails with memory errors | Use low_memory=True option |

Pre-filter data; use appropriate cofactor transformation |

| Over-clustering | Spurious clusters appearing | Set disconnection_distance parameter |

Understand distance metric; inspect k-NN graph |

| Poor Visualization | Dense blobs without internal structure | Reduce point size; use Datashader | Experiment with spread and min_distance parameters |

| Global Structure Loss | Relative cluster positions meaningless | Compare with PaCMAP or DenSNE | Validate with multiple dimensionality reduction methods |

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Standardized Workflow for High-Dimensional Cytometry Analysis

The following integrated protocol ensures reproducible analysis across different technologies and experimental conditions, with particular emphasis on standardization for research reproducibility.

Protocol Title: Standardized Computational Analysis of High-Dimensional Cytometry Data

Purpose: To provide a reproducible pipeline for unbiased identification and characterization of cellular populations from high-dimensional cytometry data.

Materials and Reagents:

- Transformed cytometry data (FCS or CSV files) exported after compensation and initial quality control

- Metadata file containing sample information and experimental conditions

- Computational environment: R with cyCONDOR package or Docker container lorenzobonaguro/cycondor:v030 [34]

- Hardware: Consumer-grade computer with sufficient RAM (16GB minimum recommended for moderate datasets)

Procedure:

Data Pre-processing and Transformation

- Export data from acquisition software in FCS or CSV format

- Apply arcsinh transformation with technology-appropriate cofactors:

- Perform basic gating to remove debris and doublets prior to import if computational resources are limited [4]

Data Integration and Quality Control with cyCONDOR

Cellular Population Identification with FlowSOM

- Set the number of meta-clusters based on biological question (higher numbers for rare populations)

- Execute FlowSOM clustering through cyCONDOR interface

- Examine star charts for marker expression patterns to guide biological interpretation

Dimensionality Reduction and Visualization with UMAP

- Run UMAP with default parameters initially (min_distance=0.1, spread=1.0)

- Adjust UMAP parameters based on dataset characteristics:

- Increase min_distance to reduce clumping if clusters appear overly compact

- Adjust spread parameter to balance local vs. global structure preservation

- Generate visualizations with appropriate point sizing to reveal internal cluster structure [36]

Biological Interpretation and Validation

- Perform differential expression analysis between experimental conditions

- Annotate cell populations based on marker expression patterns

- Validate computationally identified populations using orthogonal methods such as manual gating or functional assays

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If UMAP produces spurious clusters, check for disconnected vertices using

umap.utils.disconnected_vertices()and consider adjusting thedisconnection_distanceparameter [36] - If FlowSOM fails to identify expected populations, verify data transformation and experiment with different cluster resolutions

- For memory issues with large datasets, utilize cyCONDOR's subsampling functionality or increase virtual memory allocation

Comparative Analysis and Tool Selection Framework

Strategic Tool Selection Guide

Each computational tool addresses specific challenges in the high-dimensional cytometry analysis pipeline. The following comparative analysis provides guidance for tool selection based on experimental objectives:

Table 3: Tool Selection Guide Based on Experimental Objectives

| Experimental Goal | Recommended Tool | Rationale | Key Parameters | Validation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exploratory Population Discovery | FlowSOM through cyCONDOR | Efficient handling of large datasets; clear visualization of relationships via minimal spanning trees | Number of meta-clusters | Comparison with manual gating; functional assays |

| Disease Classification | cyCONDOR with built-in ML | Integrated machine learning for sample classification based on clinical characteristics | Classification algorithm type; feature selection | Cross-validation; independent cohort testing |

| Trajectory Analysis | cyCONDOR with Slingshot | Pseudotime analysis for developmental processes or disease progression | Starting cluster definition | Marker expression kinetics; developmental markers |

| Publication-Quality Visualization | UMAP with parameter tuning | Preservation of global data structure; customizable visualization options | mindistance, spread, nneighbors | Comparison with multiple DR methods |

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for High-Dimensional Cytometry Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| cyCONDOR | Integrated end-to-end analysis platform | R package, Docker container | GitHub: lorenzobonaguro/cyCONDOR [34] |

| FlowSOM | Self-organizing map clustering | R package, integrated in multiple platforms | Available in cyCONDOR, CRUSTY [33] |

| UMAP | Dimensionality reduction | Python (umap-learn), R (uwot) | Integrated in cyCONDOR, CRUSTY [4] [33] |

| CRUSTY | Web-based analysis platform | Python/Scanpy, web interface | https://crusty.humanitas.it/ [33] |

| Harmony | Batch integration | R package, integrated in cyCONDOR | Batch effect correction [4] |

The integration of cyCONDOR, FlowSOM, and UMAP provides researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for unbiased analysis of high-dimensional cytometry data. cyCONDOR serves as the orchestrating platform that unifies data pre-processing, clustering, dimensionality reduction, and advanced analytical functions like pseudotime analysis and disease classification [4] [34]. FlowSOM offers an efficient engine for cellular population identification through self-organizing maps [33], while UMAP enables intuitive visualization that preserves both local and global data structure better than many alternatives [36] [32]. Together, these tools facilitate the extraction of biologically meaningful insights from complex datasets while promoting analytical standardization and reproducibility—critical considerations for both basic research and clinical translation in the era of high-dimensional single-cell technologies.

Fundamental Concepts: High-Dimensional Cytometry Analysis

What constitutes an end-to-end workflow for high-dimensional cytometry data?

An end-to-end workflow for high-dimensional cytometry data encompasses a complete pipeline from raw data preparation to final biological interpretation. This integrated process includes data ingestion and transformation, quality control and cleaning, batch correction, dimensionality reduction, and unsupervised clustering, followed by visualization and statistical testing [4]. Tools like cyCONDOR provide unified ecosystems that streamline these steps, reducing the number of functions needed from nine in some platforms to just four for core analysis steps, significantly enhancing accessibility for non-computational biologists [4].

Why is preprocessing considered crucial for successful clustering?

Preprocessing is fundamental because clustering algorithms are highly sensitive to data preparation. Scaling, normalization, or projections like PCA can drastically alter cluster shapes and boundaries [37]. Without proper preprocessing, distance-based algorithms like K-Means will be biased toward features with larger numeric ranges, potentially obscuring true biological signals. Studies demonstrate that automated preprocessing pipelines can improve silhouette scores from 0.27 to 0.60, indicating substantially better-defined clusters [37].

Preprocessing Phase: Data Preparation and Quality Control

What are the essential preprocessing steps for high-dimensional cytometry data?

Table 1: Essential Preprocessing Steps for High-Dimensional Cytometry Data

| Processing Step | Purpose | Common Tools/Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Data Cleaning | Remove technical artifacts and poor-quality events | FlowCut, FlowAI [38] |

| Compensation | Correct for fluorescent dye spillover | CompensateFCS, instrument software [39] |

| Transformation | Make data distribution compatible with downstream analysis | Logicle, arcsinh [39] |

| Normalization | Reduce technical variation between samples | Per-channel normalization [39] |

| Gating | Remove debris, doublets, and dead cells | Manual gating in FlowJo, automated gating [4] |

| Downsampling | Reduce computational demand for large datasets | Interval downsampling, density-dependent downsampling [38] |

How should I handle data transformation and normalization?

Data transformation should be performed using Logicle or arcsinh functions to properly display fluorescence signals that range down to zero and include negative values after compensation [39]. For normalization, per-channel approaches are recommended to correct for between-sample variation in large-scale datasets, such as those from multi-center clinical trials [39]. The specific transformation method should be selected based on your instrumentation and downstream analysis requirements, with tools like FCSTrans automatically identifying appropriate transformation methods and parameters [39].

What quality control issues commonly arise during preprocessing?

Common issues include saturated events (parameter values at maximum recordable scale), high background scatter, suboptimal scatter profiles, and abnormal event rates [40] [39]. Saturated events are particularly problematic for clustering algorithms as they can create groups with zero variance in certain dimensions. Solutions include removing these events or adding minimal noise to prevent algorithmic issues [39]. For scatter profile issues, ensure proper instrument settings, use fresh healthy cells for setting FSC and SSC, and eliminate dead cells and debris through sieving [40].

Dimensionality Reduction: Techniques and Applications

What are the most used dimensionality reduction methods, and how do they compare?

Table 2: Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Methods for High-Dimensional Cytometry

| Method | Preservation Focus | Execution Time | Strengths | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Global structure | ~1 second | Very fast; good for initial exploration | R, Python, various platforms [41] |

| t-SNE | Local structure | ~6 minutes | Excellent separation of distinct populations | FlowJo, Cytobank, Omiq, R, Python [41] |

| UMAP | Local structure (better global than t-SNE) | ~5 minutes | Preserves more global structure than t-SNE | FlowJo (plugin), FCS Express, R, Python [41] |

| PHATE | Local and global structure | ~7 minutes | Captures branching trajectories | FlowJo (plugin), R, Python [41] |

| EmbedSOM | Balanced local/global | ~6 seconds | Very fast; uses self-organizing maps | FlowJo (plugin), R [41] |

How do I choose between t-SNE and UMAP for my dataset?

Select t-SNE when your primary goal is visualizing and identifying distinct cell populations within a dataset, as it provides excellent preservation of relationships between similar cells [41]. Choose UMAP when you need better preservation of some global structure and faster processing for very large datasets [41] [42]. Note that both methods focus primarily on local structure, so distances between well-separated clusters should not be overinterpreted. UMAP tends to produce more compressed clusters with greater white space between them compared to t-SNE's more continuous appearance [41].

What are the key parameters to optimize for dimensionality reduction?

For t-SNE, the perplexity parameter is most critical, as it determines how many neighboring cells influence each point's position [41]. Higher values better preserve global relationships. For UMAP, key parameters include number of neighbors (balancing local versus global structure) and minimum distance (controlling cluster compaction) [42]. For all methods, proper data scaling is essential before dimensionality reduction, as variance-based methods will be dominated by high-expression markers without appropriate transformation [41] [37].

Figure 1: Data Preprocessing Workflow for High-Dimensional Cytometry

Clustering and Biological Interpretation

What clustering algorithms are most effective for high-dimensional cytometry data?

Phenograph and FlowSOM are widely adopted clustering methods for high-dimensional cytometry data [4]. FlowSOM is particularly valued for its speed and integration with visualization tools, while Phenograph effectively identifies rare populations in complex datasets. The choice between algorithms depends on your specific objectives: for comprehensive population identification, Phenograph may be preferable, while for rapid analysis of large datasets, FlowSOM offers advantages. cyCONDOR implements multi-core computing for Phenograph, significantly improving its runtime for large datasets [4].

How can I validate my clustering results?

Cluster validation should employ multiple approaches: internal metrics (silhouette score, Davies-Bouldin index, Calinski-Harabasz score) assess compactness and separation; biological validation confirms that clusters correspond to biologically meaningful populations; and comparison with manual gating establishes consistency with established methods [37]. For automated pipeline optimization, silhouette score is commonly used as it measures both cluster cohesion and separation [37].