Validating Multi-Organ-on-a-Chip Systems to Recapitulate Human Immunity for Next-Generation Therapeutic Development

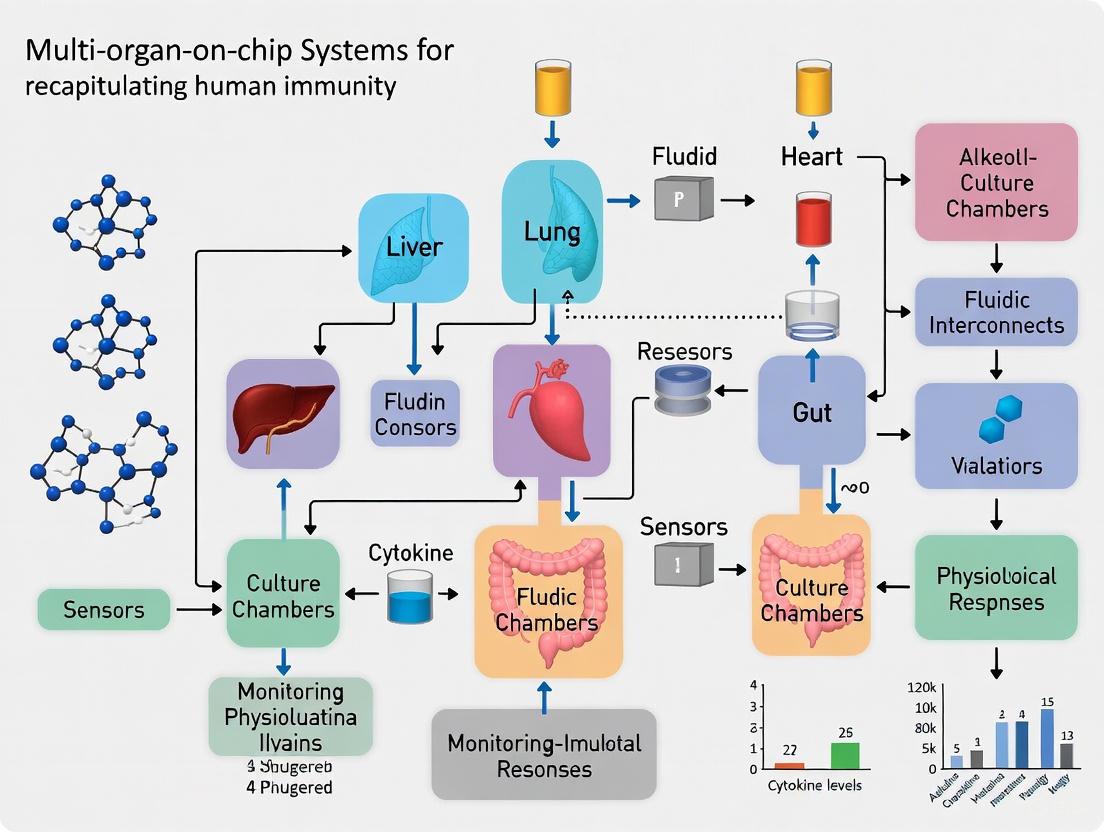

This article explores the groundbreaking role of validated multi-organ-on-a-chip (MOC) systems in revolutionizing preclinical research by accurately modeling human immune responses.

Validating Multi-Organ-on-a-Chip Systems to Recapitulate Human Immunity for Next-Generation Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article explores the groundbreaking role of validated multi-organ-on-a-chip (MOC) systems in revolutionizing preclinical research by accurately modeling human immune responses. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis spanning the foundational principles of microphysiological systems (MPS), their methodological applications in immunotherapy and toxicology, strategies for overcoming critical technical challenges, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing the latest advancements, this resource aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to leverage these human-relevant platforms for enhancing drug efficacy, predicting systemic toxicity, and accelerating the development of personalized immunotherapies, thereby bridging a critical gap between animal studies and clinical trials.

The Foundation of Immunity-on-a-Chip: Principles and System Design

Defining Multi-Organ-on-a-Chip (MOC) and Microphysiological Systems (MPS)

Microphysiological Systems (MPS) are advanced in vitro platforms that mimic the functional units of human organs at a miniature scale. They represent a technological evolution from traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell culture, incorporating three-dimensional (3D) structures, dynamic fluid flow, and biomechanical cues to recreate tissue- and organ-level physiology more accurately [1]. MPS encompass a range of technologies, including organoids and 3D bioprinted tissues [2]. Their primary purpose is to provide a more human-relevant experimental platform for biomedical research, drug development, and toxicology testing, thereby reducing reliance on animal models, which often poorly predict human responses [1] [3].

A Multi-Organ-on-a-Chip (MOC) is a specific type of MPS that interconnects two or more individual organ models via microfluidic channels. This creates a simulated "human-on-a-chip" that enables the study of complex organ-organ interactions, such as organ crosstalk, the pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) of drugs, and off-target toxicity [4] [2]. By linking organs, MOCs aim to replicate the systemic responses of the human body to therapeutic compounds, offering a powerful tool for predicting efficacy and safety in preclinical trials [5].

Comparative Analysis of MPS Platforms and Applications

The landscape of MPS technologies is diverse, with platforms differing in their design, throughput, and specific applications. The table below summarizes how MPS compare to traditional preclinical models and highlights the specifications of leading commercial platforms.

Table 1: Preclinical Model Comparison and Commercial MPS Platforms

| Feature | In vitro 2D Cell Culture | In vitro 3D Spheroid | In vivo Animal Models | Microphysiological System (MPS) | Emulate AVA System | CN Bio PhysioMimix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Relevance | Low | Medium | Low (due to species differences) | Medium / High | High (Human cell-based) | High (Human cell-based) |

| Complex 3D Organs/Tissues | No | Limited (Avascular) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Blood)/Flow Perfusion | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes (Microfluidic) | Yes (Tubeless microfluidics) |

| Multi-organ Capability | No | No | Yes (Systemic) | Yes | Via linking chips | Yes (Single- to multi-organ) |

| Longevity | < 7 days | < 7 days | > 4 weeks | ~ 4 weeks | Up to 7-day experiments | Up to 4 weeks |

| New Drug Modality Compatibility | Low | Medium | Low | Medium / High | High (Antibody-drug conjugates, Cell therapies) | High (mAbs, oligonucleotides, AAVs) |

| Throughput | High | High | Low | Variable (Medium to High) | High (96 chips per run) | High (Up to 288 samples) |

| Key Advantages | Simple, cheap, high-throughput | Better cell-cell interaction than 2D | Intact systemic physiology | Human-relevant, mechanistic insights, reduces animal use | High-throughput, automated imaging, AI-ready datasets | Open architecture, PDMS-free, validated protocols |

| Documented Applications | Basic cell functions | Cancer cell research, initial drug screening | Pharmacology, PK/PD, toxicity | ADME, toxicity, disease modeling, personalized medicine [3] | Toxicological and ADME studies [6] | Safety toxicology, ADME, disease modeling [3] |

Beyond commercial platforms, academic and institutional research continues to push the boundaries of complexity. A landmark 2025 study detailed an eighteen-organ MOC that incorporated a physiologically realistic vascular network and an excretory system with a micro-stirrer to mimic kidney function [2]. This system demonstrated the capability to maintain viability for almost two months and successfully modeled two-compartment pharmacokinetics, a task challenging for simpler in vitro models [2]. Furthermore, MPS are proving invaluable in specialized fields like cancer research and immunology. For instance, Pfizer has shared data on a Lymph Node-on-a-Chip capable of predicting antigen-specific immune responses, a significant advance for preclinical immunotoxicity testing [6].

Experimental Validation: Recapitulating Human Biology

Validating MOC models requires demonstrating that they replicate key structural and functional characteristics of human physiology. The following case studies and experimental data highlight this process.

Case Study: Building Blocks of Learning in a Neural MPS

A 2025 study used a brain MPS (neural organoids) to investigate the foundations of learning and memory. The researchers conducted a multi-faceted validation to confirm the model's relevance for neurophysiological studies [7].

Table 2: Key Experimental Findings in a Neural MPS Model

| Biological Process Investigated | Experimental Readout/Metric | Key Finding in Neural MPS | Technique/Method Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synapse Formation | Presence of pre- and post-synaptic markers | Detected punctate staining for Synaptophysin (presynaptic) and HOMER1 (postsynaptic) [7] | Immunofluorescence staining |

| Receptor Expression | Gene expression of key neurotransmitter receptors | Expression of glutamatergic (GRIN1, GRIN2A, GRIN2B, GRIA1) and GABAergic (GABRA1) receptors increased over time, plateauing at maturity (weeks 8-12) [7] | RNA-sequencing, qPCR |

| Immediate Early Gene (IEG) Expression | Basal and evoked expression of IEGs (e.g., FOS, NPAS4, NR4A1) | Organoids showed basal IEG expression, which was modulated by chemical stimuli, indicating activation of pathways critical for memory [7] | RNA-sequencing, Immunofluorescence |

| Synaptic Plasticity | Neuronal response to Theta Burst Stimulation (TBS) | Input-specific TBS induced short-term potentiation (STP) and long-term potentiation (LTP), the cellular correlates of learning and memory [7] | High-Density Microelectrode Arrays (HD-MEAs), Pharmacological modulation |

| Network Dynamics | Functional connectivity and criticality analysis | Organoids exhibited highly interconnected neural networks with critical dynamics, which optimize information encoding and processing [7] | Calcium imaging, HD-MEA data analysis |

Experimental Protocol: Investigating Synaptic Plasticity in a Neural MPS

The following workflow, derived from the same study [7], details the key steps for a functional investigation of synaptic plasticity.

Case Study: A Vascularized Multi-Organ MOC for Pharmacokinetics

The aforementioned eighteen-organ MOC was rigorously validated for its ability to mimic systemic drug disposition [2]. A key experiment involved characterizing the "blood" circulation to ensure physiological relevance. The design achieved a "blood" flow distribution across the 18 organ compartments that closely mimicked in vivo patterns in animal models, a critical prerequisite for meaningful pharmacokinetic studies [2]. The system's integrated excretion system, featuring a dialysis membrane and a micro-stirrer, allowed researchers to adjust the elimination rate of small molecules, thereby replicating a fundamental pharmacokinetic process typically absent in vitro models [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Building and running a successful MOC experiment requires a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The selection is critical for ensuring biological relevance, reproducibility, and accurate data collection.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MOC Studies

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance in MOC Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Sources | Primary human hepatocytes [1], Primary gut epithelial & goblet cells [4], HepaRG cell line [1], Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) [5], Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) [7] | Forms the biological foundation of the organ model. Primary cells and PDOs offer high physiological relevance, while immortalized lines offer consistency. hiPSCs enable patient-specific models. |

| Chip/MPS Hardware | Emulate Chip-R1 (Rigid, plastic) [6], CN Bio PhysioMimix Multi-chip Plates (PDMS-free, COC) [3] [4], PDMS-based chips [1] | The physical platform that houses the cells and microfluidics. Material choice is critical; PDMS can absorb small drugs, skewing results, while materials like COC (cyclic olefin copolymer) minimize non-specific binding [4]. |

| Scaffolds & Matrices | Extracellular matrix (ECM) components [1], Hydrogels [6], 3D bioprinting bioinks [5] | Provides the 3D structural and biochemical support for cells, mimicking the native tissue microenvironment. Essential for proper cell differentiation, organization, and function. |

| Culture Media | Customized culture medium [2], Cell-type specific media | Supplies nutrients, growth factors, and hormones to sustain cell viability and function. Recirculating media in MOCs enables systemic signaling between organ compartments. |

| Sensors & Assays | Embedded sensors for pH, O₂ [8], Effluent collection for -omics and biomarker analysis [6] [3], High-Density Microelectrode Arrays (HD-MEAs) [7] | Enables real-time monitoring of the microenvironment and post-experiment analysis of drug metabolites, secreted biomarkers, and tissue transcriptomics/proteomics. |

Multi-Organ-on-a-Chip technology, situated within the broader field of Microphysiological Systems, has moved from a promising concept to a powerful, validated tool for biomedical research. By integrating multiple human organ models with physiologically relevant features like vascular flow and excretory functions, MOCs offer a uniquely human-relevant platform for modeling systemic drug pharmacokinetics, organ-organ crosstalk, and complex disease states. As validation studies, such as those demonstrating neural plasticity and multi-organ pharmacokinetics, continue to accumulate, the scientific and regulatory confidence in these systems grows. This progress, supported by a robust toolkit of reagents and commercial platforms, is paving the way for MOCs to reduce the high failure rates in drug development and usher in a new era of precision medicine.

The convergence of microfluidics, three-dimensional (3D) cell culture, and integrated sensing is revolutionizing the development of in vitro models, particularly in the quest to create validated multi-organ-on-chip (multi-OoC) systems that recapitulate human immunity. Traditional drug development suffers from high failure rates, in part because conventional 2D cell cultures and animal models poorly predict human physiological responses [9] [10]. Microphysiological Systems (MPS), or Organ-on-Chip (OoC) technologies, address this gap by combining micro-engineered environments with living human cells to create more physiologically relevant models [9]. The incorporation of a functional immune system is a critical frontier for these models, as immunity underlies the pathophysiology of nearly every human disease, from cancer and infection to autoimmunity [10]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the core technological components—3D cell culture matrices, microfluidic flow, and sensing modalities—that are essential for building immunocompetent multi-OoC platforms, providing experimental data and protocols to inform their selection and use.

Comparative Analysis of 3D Cell Culture Matrices

The transition from two-dimensional (2D) to three-dimensional (3D) cell culture is fundamental to creating in vivo-like microenvironments in organ-on-chip systems. Cells grown in 3D exhibit significant differences in morphology, differentiation, viability, gene expression, and drug metabolism compared to their 2D counterparts [11]. Selecting an appropriate 3D scaffold is therefore a critical first step in model development.

Types of 3D Cell Culture Scaffolds

The table below compares the four primary methods for incorporating 3D cell culture into microfluidic devices [12] [13].

| Method | Description | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspension/Hanging Drop | Cells aggregate into spheroids in suspended media droplets [12] [13]. | Simple setup; homogeneous spheroid formation; high-throughput potential [12] [13]. | Limited to non-adherent or spheroid-forming cells; poor control over ECM composition [12]. | Embryoid bodies, tumor spheroids, mammospheres [13]. |

| Hydrogel Scaffolds | Cells are encapsulated within a hydrated polymer network that mimics the native extracellular matrix (ECM) [12] [14]. | Excellent biomimicry of ECM; tunable mechanical and biochemical properties; high porosity for nutrient diffusion [12] [14]. | Batch-to-batch variability (natural hydrogels); potential lack of mechanical rigidity [13] [14]. | Tissue engineering, drug screening, studying cell migration and invasion [12] [14]. |

| Paper-Based Scaffolds | Cells are seeded onto a porous, fibrous cellulose matrix [12] [13]. | Inexpensive; commercially available; facile stacking to create complex 3D structures [12] [13]. | Fiber size (>1µm) is larger than native ECM (~500nm); poor mimicry of ECM composition [13]. | Low-cost diagnostic assays, fundamental cell proliferation studies [12]. |

| Fiber-Based Scaffolds | Cells grow on synthetic or natural nano- to micro-scale fibers created by techniques like electrospinning [12] [13]. | Combines advantages of hydrogels and paper; highly tunable fiber size, composition, and alignment; excellent stability [12] [13]. | Complex fabrication process; requires specialized knowledge for development [13]. | Co-culture systems, studying endothelial cell morphogenesis and migration [12] [13]. |

Hydrogel Materials: A Deeper Dive

Given their widespread use, the choice of hydrogel material is crucial. The table below lists common hydrogels and their specific functions in microfluidic cell culture [14].

| Hydrogel Name | Origin | Primary Function in Culture | Example Composites (Cells, Drugs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen | Natural | Barrier, Drug Screening | Primary human kidney cells; cisplatin [14] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Synthetic | Cell Delivery, Encapsulation | Hepatocytes, leukemia cells, stem cells [14] |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | Natural | Drug Screening/Delivery | Prostate cancer cells; camptothecin, docetaxel [14] |

| Alginate | Natural | Encapsulation, Drug Delivery | Hybridoma cells; mouse breast cancer cells; Vitamin B12 [14] |

| PuraMatrix | Synthetic | Drug Screening | Breast cancer, lung cancer, microvascular endothelial cells [14] |

| Fibrin | Natural | Cell Delivery | Not specified in search results [14] |

The Impact of Microfluidic Flow in MPS

Microfluidic flow is a defining feature of OoC systems, enabling dynamic perfusion that can significantly influence cell phenotype and function.

Quantitative Impact of Perfusion vs. Static Culture

A 2023 meta-analysis of 1718 ratios from 95 articles provides robust, quantitative data on how perfusion affects various cell types and biomarkers compared to static culture [15]. The gains from perfusion are not uniform but are highly dependent on the cell type and the specific biomarker measured.

| Cell Type / System | Key Biomarkers/Responses Enhanced by Perfusion | Reported Fold-Change (Flow vs. Static) | Context / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| General 2D Cultures | Most biomarkers | Overall very little improvement [15] | Perfusion alone in 2D settings shows minimal benefit. |

| General 3D Cultures | Cellular functions | Slight improvement [15] | High-density cultures benefit more from enhanced mass transfer. |

| CaCo2 (Intestinal) | CYP3A4 activity | >2-fold induction [15] | One of the most consistent biomarker inductions. |

| Hepatocytes (Liver) | PXR mRNA levels | >2-fold induction [15] | Key regulator of xenobiotic metabolism. |

| Blood Vessel Walls | Specific biomarkers | Reacted most strongly [15] | Cell types are naturally shear-sensitive. |

| Tumours, Pancreatic Islet, Liver | Specific biomarkers | Reacted strongly [15] | Highlights importance of flow for metabolic tissues. |

| Reproducibility | Various biomarkers | Low between articles [15] | 52 of 95 articles showed inconsistent responses for a given biomarker. |

Advanced Flow Systems for Immunity

For immunocompetent models, flow enables the study of complex processes like immune cell recruitment and extravasation. Advanced systems go beyond simple perfusion:

- Single-Phase Flow Culture: Uses microchambers and channels for well-defined, continuous perfusion, allowing for co-cultures and integration of sensors for parameters like dissolved oxygen (DO) and pH [16].

- Droplet-Based Culture: Encapsulates single cells or small populations in picoliter to nanoliter water-in-oil droplets, enabling ultra-high-throughput screening (up to 10^7 droplets) and analysis of cellular heterogeneity [16].

Integrated Sensing for Real-Time Monitoring

Integrating sensors directly into MPS is critical for non-invasive, real-time monitoring of both the cellular microenvironment and tissue functionality, moving beyond endpoint analyses.

Sensing Modalities

The following table details key sensing modalities that can be integrated into microfluidic MPS.

| Sensing Modality | Measured Parameter | Biologically Relevance | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transepithelial/Transendothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) | Barrier Integrity | Key indicator of tissue health and model maturity, especially in barriers like intestine, lung, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) [17] [10]. | Integrated gold electrodes in an OSTE-based chip measured TEER before and after pulsed electric field treatment [17]. |

| Electrochemical Sensors | Oxygen, pH, Glucose, Lactate | Metabolic activity of tissues; indicators of cell viability and inflammatory responses [17] [10]. | An OSTE-based chip with integrated sensors monitored oxygen and pH shifts in real-time following cell treatment [17]. |

| Optical Sensors | Oxygen, pH | Non-invasive monitoring of the physicochemical microenvironment [17]. | Oxygen "sensor spots" were integrated upstream and downstream of a treatment chamber for localized monitoring [17]. |

Case Study: A Sensor-Integrated MPS

A 2024 study demonstrated a microphysiological system fabricated from Off-Stoichiometry Thiol-Ene (OSTE) polymer, which avoids the small molecule absorption issues of PDMS [17]. This chip featured:

- Integrated Electrodes: Used for both applying Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) and measuring TEER.

- Optical Sensors: For monitoring oxygen concentration and pH in the microchannel. The system successfully treated C6 glioma cells with PEF and detected subsequent physiological changes: a decrease in oxygen concentration without PEF, an increase with PEF, and a pH shift towards alkalinity post-PEF [17]. This showcases the power of integrated sensing for capturing dynamic cellular responses.

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol: Assessing On-Target, Off-Tumor Toxicity of T-Cell Bispecific Antibodies (TCBs)

This protocol, adapted from Kerns et al. (2021), details the use of a human Alveolus Lung-Chip to evaluate the safety profile of cancer immunotherapeutics [18].

Objective: To reproduce and predict target-dependent TCB safety liabilities in a human immunocompetent organ chip platform.

Materials:

- Organ-Chip Platform: Human Alveolus Lung-Chip (e.g., from Emulate) featuring two parallel microchannels separated by a porous, ECM-coated membrane [18].

- Cells: Human primary alveolar epithelial cells and human primary lung microvascular endothelial cells.

- Immune Cells: Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) isolated from human whole blood.

- Test Article: T-cell bispecific antibodies (TCBs) with known target (e.g., FOLR1) and control molecules.

Workflow Diagram: Lung-Chip Toxicity Assay

Procedure:

- Chip Seeding and Maturation: Seed alveolar epithelial cells in the top channel and lung microvascular endothelial cells in the bottom channel. Culture under liquid-liquid conditions for 5 days, then establish an air-liquid interface (ALI) for an additional 5 days to promote tissue maturation [18].

- Target Expression Validation: Use flow cytometry and immunofluorescence to confirm the expression level and pattern of the TCB target antigen (e.g., FOLR1) on the chip's epithelium. Compare to expression in positive control tumor cell lines [18].

- Introduction of Immune Compartment: Add PBMCs to the epithelial channel of the mature chip to create an immunocompetent system [18].

- TCB Exposure: Introduce the TCB into the system via the fluidic flow.

- Endpoint Analysis: Monitor the chips for 1-3 days for signs of toxicity.

- Cytokine Release: Measure levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-2, IL-8) in the effluent using ELISA.

- Immune Cell Activation and Infiltration: Use real-time imaging to visualize T-cell attachment to the epithelium and morphological changes.

- Epithelial Damage: Quantify barrier integrity by measuring Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) and assess cell death via staining for viability/cytotoxicity markers [18].

Protocol: Real-Time Monitoring of Barrier Function and Metabolism

This protocol outlines the use of a sensor-integrated MPS for continuous monitoring.

Objective: To non-invasively track barrier integrity and metabolic shifts in a 3D tissue model under flow.

Materials:

- MPS Platform: A microfluidic chip with integrated electrodes for TEER and optical/electrochemical sensors for oxygen and pH (e.g., as described in [17]).

- Cells: Relevant barrier-forming cells (e.g., endothelial cells, intestinal epithelial cells) potentially co-cultured with other tissue-specific cells in a 3D hydrogel.

Procedure:

- Chip Preparation and Cell Seeding: Load the chip with a cell-laden hydrogel (e.g., collagen or Matrigel) in the central chamber. Initiate continuous, low-flow perfusion of culture media.

- Baseline Recording: Once cells adhere and form initial contacts, begin continuous recording of TEER, oxygen concentration (upstream and downstream of the tissue), and media pH. Continue until values stabilize, indicating the formation of a mature barrier and stable metabolic activity.

- Experimental Intervention: Introduce the test compound (e.g., a drug, inflammatory cytokine, or toxin) into the media stream.

- Real-Time Data Acquisition: Continuously monitor the sensor outputs throughout the exposure period and during a recovery phase (if applicable).

- A drop in TEER indicates a loss of barrier integrity.

- Changes in the oxygen gradient across the tissue reflect alterations in metabolic activity.

- A shift in media pH can indicate changes in glycolytic flux or other metabolic pathways [17].

- Correlation with Endpoint Assays: At the end of the experiment, perform endpoint analyses (e.g., immunofluorescence, gene expression) on the tissue and correlate findings with the kinetic sensor data.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs key materials and reagents essential for building and operating immunocompetent MPS, as cited in the research.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Material for microfluidic device fabrication [12] [17]. | Gas permeable, optically transparent, easy to mold; but can absorb small molecules [12] [17]. |

| Off-Stoichiometry Thiol-Ene (OSTE) | Alternative polymer for microfluidic device fabrication [17]. | Reduced small molecule absorption, biocompatible, good alternative to PDMS for drug studies [17]. |

| PuraMatrix | Synthetic, peptide-based hydrogel for 3D cell culture [14]. | Defined composition, self-assembling into nanofibrous scaffold, suitable for drug screening co-cultures [14]. |

| PEG-DA (Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Diacrylate) | Synthetic hydrogel for cell encapsulation and delivery [14]. | Tunable mechanical properties, photopolymerizable for precise patterning within microchannels [14]. |

| Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | Source of human immune cells for immunocompetent models [18] [10]. | Provide T cells, B cells, NK cells, and monocytes; can be isolated from blood of specific donors [18]. |

| Transepithelial/Transendothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) Electrodes | Integrated sensors for quantifying barrier integrity in real-time [17]. | Typically gold or other inert metals; can be multiplexed with other sensor functions [17]. |

| Oxygen Sensor Spots | Optical sensors for non-invasive monitoring of dissolved oxygen [17]. | Can be glued inside microchannels; read by an external fluorescence detector [17]. |

The strategic integration of microfluidics, physiologically relevant 3D cell cultures, and real-time sensing is paramount for developing validated multi-organ-on-chip systems that can accurately model human immunity. The experimental data and comparisons presented in this guide demonstrate that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. The choice of 3D matrix—whether hydrogel, spheroid, or scaffold—must be tailored to the specific organ and biological question. The application of microfluidic flow shows clear, though variable, benefits in enhancing the physiological relevance of cellular phenotypes, particularly in 3D cultures and for specific biomarkers. Finally, the integration of sensing technologies for parameters like TEER, oxygen, and pH is transitioning MPS from static endpoint analysis tools to dynamic platforms capable of capturing the complex kinetics of immune and tissue responses. As these core components continue to mature and standardize, their combined power will unlock more predictive models for drug development and the study of human disease.

Engineering the Immune-Tumor Microenvironment (TME) on a Chip

The tumor microenvironment (TME) represents a complex ecosystem where cancer cells interact with immune components, stromal cells, and extracellular matrix in a dynamic interplay that critically influences disease progression and therapeutic response [19] [20]. Engineering the immune-TME on a chip has emerged as a transformative approach to overcome the limitations of traditional models, offering unprecedented precision in mimicking human physiology for cancer research and drug development [19]. These microfluidic platforms integrate immune system components with tumor models within architecturally and biochemically defined contexts, enabling systemic analysis of immune-tumor interactions under fluidically dynamic conditions that more accurately reflect in vivo realities [5].

The validation of multi-organ-on-chip systems recapitulating human immunity represents a critical frontier in preclinical research, addressing the significant translational gap between animal models and human clinical outcomes [21]. By preserving key histopathological, genetic, and phenotypic features of parent tumors while incorporating functional immune elements, these chips provide a physiologically relevant platform for investigating immune surveillance, evasion mechanisms, and therapeutic interventions [5] [20]. This guide objectively compares leading immune-TME chip platforms, their performance metrics, and experimental applications to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Technology Comparison: Platform Capabilities and Specifications

Commercial Immune-TME Platform Comparison

Table 1: Comparative analysis of commercial platforms for immune-TME modeling

| Platform Feature | Emulate Organ-Chip | MIMETAS OrganoPlate | ChipShop Fluidic 480 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic Design | Multi-channel with mechanical stretch capabilities | 3-lane 40-chip plate, membrane-free | Cross-flow membrane chip, two independent chambers |

| Throughput Capacity | Medium | High (96 tissues per plate) | Medium |

| Key Analytical Tools | Integrated software for barrier function, immune cell recruitment, CAR-T analysis [22] | PhaseGuide technology for ECM patterning, gravity-driven flow [23] | Permeable membrane for tissue interface formation |

| Imaging Compatibility | Standard microscopy systems | High-content confocal imaging compatible [23] | Standard microscopy systems |

| Primary Applications | Barrier integrity studies, immune cell recruitment, CAR-T cell therapy assessment [22] | Angiogenesis, neurite outgrowth, permeability studies [23] | Gut-on-chip, brain-on-chip, multi-tissue interfaces |

| Flow Control System | Proprietary perfusion systems | Gravity-driven flow (no external pumps) [23] | Compatible with external flow controllers (e.g., Elveflow) [24] |

Performance Metrics in TME Recapitulation

Table 2: Quantitative performance assessment of immune-TME chip models

| Performance Parameter | Traditional 2D Models | 3D Organoids | Immune-TME Chips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Heterogeneity Preservation | Limited (<20%) [5] | High (>87% in colorectal PDOs) [5] | High (up to 95% by vascular integration) [5] |

| Immune Cell Infiltration Capacity | Non-existent | Limited | High (controlled recruitment assays) [22] |

| Angiogenic Sprouting Measurement | Not possible | Possible but static | Quantitative (sprout number, length, volume) [23] |

| Drug Response Prediction Accuracy | 30-40% | 70-87% [5] | 85-95% (vascularized models) [5] |

| Multicellular Complexity | Low (1-2 cell types) | Medium (3-4 cell types) | High (5+ cell types with spatial control) [19] |

| Physiological Flow Shear Stress | Absent | Absent | Tunable (0.1-20 dyn/cm²) [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Immune-TME Modeling

Protocol 1: Vascularized Tumor-Immune Chip Assembly

This protocol establishes a perfusable vascular network integrated with tumor organoids and immune components for evaluating trafficking and therapeutic responses [5].

Day 1: Microfluidic Device Preparation

- Select appropriate chip architecture (e.g., 3-lane OrganoPlate or parallel channel designs)

- Treat chip surfaces with 0.1% pluronic F-127 for 30 minutes to prevent non-specific adhesion

- Coat channels with collagen-I (6-8 mg/mL) or Matrigel (8-10 mg/mL) and incubate (37°C, 1 hour)

Day 1-3: Endothelial Network Formation

- Introduce HUVECs or patient-derived endothelial cells (2-3×10⁶ cells/mL) in EGM-2 medium

- Allow initial adhesion (2 hours) before initiating perfusion (0.5-1.0 µL/min)

- Culture for 3 days with stepwise flow rate increases (up to 5 µL/min) to mature vessels

Day 4: Tumor Organoid Integration

- Prepare patient-derived tumor organoids (50-100 µm diameter) in defined culture medium

- Introduce 20-30 organoids per chip into the stromal compartment

- Co-culture for 24 hours under continuous perfusion (1 µL/min) to establish tumor-endothelial contacts

Day 5: Immune Component Introduction

- Isolate PBMCs or specific immune subsets from patient blood using Ficoll gradient

- Introduce immune cells (1-2×10⁶ cells/mL) into the vascular channel

- Monitor immediate adhesion and extravasation events via time-lapse microscopy

Day 5-10: Experimental Applications

- For immunotherapy testing: Introduce checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., anti-PD-1, 10 µg/mL) via perfusion

- For immune recruitment studies: Fix and stain at specific timepoints for quantification

- For cytotoxicity assessment: Live-track immune-tumor interactions every 12 hours

Protocol 2: Immune Cell Recruitment and Cytotoxicity Assessment

This methodology quantifies immune cell migration and tumor cell killing within the engineered TME, adapted from Emulate's immune cell recruitment analysis [22].

Immune Cell Labeling and Introduction

- Isolate CD8+ T cells or NK cells from donor blood using magnetic separation

- Label with CellTracker Green CMFDA dye (5 µM, 37°C, 30 minutes)

- Wash twice with PBS and resuspend in complete RPMI at 1×10⁶ cells/mL

- Introduce labeled cells into the immune compartment of the chip

Time-Lapse Imaging and Tracking

- Place chip in environmental chamber (37°C, 5% CO₂) on confocal microscope

- Acquire images at 10-minute intervals for 24-48 hours using 10× objective

- Track individual immune cells using automated cell tracking software (e.g., MetaXpress)

Quantitative Analysis of Recruitment

- Calculate migration velocity (µm/min) from track displacements

- Determine meandering index (net displacement/total path length)

- Quantify contact duration between immune and tumor cells

- Measure apoptosis induction in tumor cells using caspase-3/7 reporters

Endpoint Immunostaining

- Fix cells with 4% PFA (15 minutes, room temperature)

- Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 (10 minutes)

- Stain for: CD8 (T cells), CD56 (NK cells), CD3 (T cells), Granzyme B (cytotoxicity)

- Image using high-content confocal system (e.g., ImageXpress Micro Confocal)

Data Analysis Parameters

- Immune cell recruitment rate: cells/mm²/hour

- Cytotoxic engagement frequency: contacts/immune cell/hour

- Target elimination efficiency: tumor cells lysed/immune cell/24h

Signaling Pathways in the Engineered Immune-TME

The engineered immune-TME on chip recapitulates critical signaling pathways that govern immune-tumor interactions. These pathways can be modulated and observed in real-time within the microfluidic environment.

Pathway 1: Anti-Tumor Immune Activation Cascade (Green) The anti-tumor immunity cycle initiates with tumor antigen release following cell death or treatment [20]. Antigen-presenting cells (dendritic cells, macrophages) process and present these antigens to T cells, leading to immune activation and proliferation [19]. Activated T cells and NK cells then execute direct cytotoxicity through perforin/granzyme release and Fas/FasL interactions, while simultaneously secreting chemotactic cytokines (CXCL9, CXCL10, CCL5) that recruit additional immune effectors to the TME [20].

Pathway 2: Tumor-Mediated Immunosuppression (Red) Tumors evade immune destruction through multiple mechanisms, including upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules (PD-L1, CTLA-4) that engage inhibitory receptors on T cells [19]. Concurrent secretion of immunosuppressive factors (TGF-β, IL-10, VEGF) and metabolic competition (tryptophan depletion via IDO, adenosine production) further dampens immune function, leading to T cell exhaustion and functional impairment [20]. These pathways can be quantitatively measured in immune-TME chips through real-time monitoring of cytokine fluxes and immune cell functional status.

Experimental Workflow for Immune-TME Validation

The validation of multi-organ-chip systems recapitulating human immunity follows a systematic workflow encompassing design, fabrication, biological integration, and functional assessment.

Phase 1: Platform Establishment Chip design incorporates microfluidic architectures that enable precise spatial organization of tumor, stromal, and immune compartments while permitting controlled perfusion [25]. Biomaterial selection ranges from natural matrices (collagen, Matrigel) to synthetic polymers (PDMS, PMMA) with specific modification to support cellular viability and function [25]. The tumor compartment can be established using patient-derived organoids, spheroids, or dissociated tumor cells that preserve original tumor heterogeneity [5] [20].

Phase 2: Application and Validation System validation requires confirmation of key TME features: immune cell extravasation, antigen-specific recognition, cytokine gradient formation, and pharmacodynamic responses to immunomodulators [19]. Functional testing includes quantifying immune-mediated cytotoxicity, profiling immune cell activation states, and measuring metabolic interactions between cellular components [22] [20]. Advanced systems may incorporate multiple organ equivalents (liver, lymph node) to study systemic immune effects and off-target toxicities [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for immune-TME chip experimentation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Immune-TME Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrices | Collagen-I (6-8 mg/mL), Matrigel (8-10 mg/mL), Fibrin (5-7 mg/mL) | Provides 3D structural support, biomechanical cues, and biochemical signals for cell organization [20] |

| Endothelial Cells | HUVECs, patient-derived endothelial cells, iPSC-ECs (2-3×10⁶ cells/mL) | Forms perfusable vascular networks enabling immune cell trafficking and nutrient delivery [5] |

| Immune Cell Media | RPMI-1640 + 10% FBS + 1% P/S, TexMACS, ImmunoCult | Maintains immune cell viability and function during perfusion culture [20] |

| Cell Tracking Dyes | CellTracker CMFDA (5 µM), CFSE (5 µM), CellTrace Violet (5 µM) | Enables real-time monitoring of immune cell migration and interactions [23] |

| Immunotherapy Agents | Anti-PD-1 (10 µg/mL), Anti-PD-L1 (10 µg/mL), Anti-CTLA-4 (10 µg/mL) | Tests checkpoint blockade efficacy in controlled TME context [19] |

| Cytokine/Chemokine Arrays | Luminex 45-plex, CBA Flex Sets, ELISA kits | Quantifies secretory profiles and gradient formation in microfluidic channels [19] |

| Microfluidic Controllers | Elveflow OB1, Fluigent MFCS, Syringe pumps | Maintains precise perfusion (0.1-20 µL/min) with physiological shear stress [24] |

| Live-Cell Imaging Dyes | Caspase-3/7 Green, Calcein AM, Propidium Iodide | Monitors real-time cytotoxicity and cell viability under flow conditions [23] |

Engineered immune-TME chips represent a validated approach for recapitulating human immunity in multi-organ systems, bridging critical gaps between conventional models and clinical reality. The technology platforms, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks presented enable researchers to quantitatively investigate immune-tumor interactions with unprecedented physiological relevance. As these systems continue to evolve through increased cellular complexity, improved biomaterials, and enhanced analytical capabilities, they promise to transform cancer immunotherapy development and personalized treatment optimization.

The successful recapitulation of human physiology in Multi-Organ-on-Chip (MOC) systems hinges on the precise engineering of key physico-chemical microenvironmental parameters. For immunology research, where cellular behavior is profoundly influenced by environmental cues, the control of fluid shear stress, chemical concentration gradients, and mechanical cues becomes paramount [26]. These parameters are not merely technical specifications but fundamental biological determinants that regulate immune cell recruitment, differentiation, activation, and inflammatory responses [27] [28].

Traditional 2D cell culture systems fail to incorporate these dynamic mechanical forces, severely limiting their physiological relevance, especially for studying interactions between immune cells, blood, and tissue barriers [3] [27]. Similarly, animal models exhibit fundamental species-specific differences in immune responses, rendering them poor predictors of human immunology [29]. Immunocompetent MOC platforms address these limitations by providing engineered microenvironments where fluid flow, mechanical forces, and biochemical gradients can be controlled to emulate in vivo-like conditions. This control enables researchers to investigate complex immune processes such as neuroinflammation, immune cell recruitment in inflammatory bowel disease, and bone marrow toxicity with unprecedented human relevance [29] [30]. The integration of these design parameters transforms MOCs from simple cellular assays into sophisticated tools capable of predicting human immune responses for drug development and disease modeling.

Quantitative Comparison of Key Parameters Across Commercial Platforms

The implementation of key design parameters varies significantly across commercial MOC platforms, influencing their applicability for specific immunology research applications. The table below summarizes the capabilities of major platforms regarding fluid shear stress, gradient generation, and mechanical cue integration.

Table: Comparison of Key Design Parameters in Commercial Multi-Organ-on-Chip Platforms

| Platform/System | Fluid Shear Stress Control | Concentration Gradient Generation | Integrated Mechanical Cues | Primary Immunology Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhysioMimix Core | Adjustable recirculating flow; rates matched to organ/tissue type [3] | Recirculating flow prevents biomarker dilution; enables clinical translatability [3] | Open architecture for customization; longer-term studies (up to 4 weeks) [3] | Safety toxicology; ADME; disease modeling [3] |

| Emulate Organ-Chips | Microfluidic flow for shear stress application [29] | Not explicitly detailed | Incorporation of organ-relevant mechanical forces (e.g., breathing motions, peristalsis) [29] | Colon immune cell recruitment; neuroinflammation; cytokine-mediated barrier disruption [29] |

| TissUse Humimic | Circulating media crucial for maintaining organ niches (e.g., bone marrow) [30] | Compartmentalization for PK/PD modeling; mass conservation for ADME [30] | 3D ceramic scaffolds for bone marrow niche; fluid flow for tissue interaction [30] | BBB permeability & neurotoxicity; bone marrow toxicity; intestine-liver ADME [30] |

| Custom Microfluidic Systems | Osmotic pumps for slow, controlled flow (<µm/s) [31] [32] | Stable, wide chemical diffusion fields alongside shear stress gradients [31] [32] | Passive generation of combined chemical and mechanical stress gradients [31] [32] | Cancer metastasis; stem cell differentiation; fundamental cell response studies [32] |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Implementation and Validation

Generating and Measuring Physiological Fluid Shear Stress

Objective: To establish physiologically relevant laminar fluid shear stress in a microfluidic device to mimic venous/arterial conditions and study its effect on immune-endothelial interactions.

Background: In vivo, endothelial cells experience wall shear stress ranging from 2-20 dyne/cm² in arteries and 1-6 dyne/cm² in veins, with critical impacts on immune cell adhesion and vascular inflammation [27]. These forces trigger morphological changes, cytoskeletal reorganization, and altered gene expression in endothelial cells [27].

Table: Physiologically Relevant Shear Stress Ranges for Different Vessel Types

| Vessel Type | Typical Shear Stress Range (dyne/cm²) | Flow Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Large Arteries (e.g., near branches) | 30 - 100 [27] | Pulsatile, Laminar |

| Small Arteries | 2 - 20 [27] | Laminar |

| Veins | 1 - 6 [27] | Laminar |

| Interstitial Flow | < a few µm/s velocity [31] [32] | Slow, Osmotically-driven |

Protocol for Setting Up Shear Stress:

- Chip Design and Calculation: For a rectangular microfluidic channel, calculate the required flow rate (Q) to achieve the target wall shear stress (τ) using the formula: τ = (6ηQ)/(h²w), where η is fluid viscosity, h is channel height, and w is channel width [27].

- Flow Control System Selection: Utilize a pressure-controlled or syringe pump system that provides precise, smooth flow without pulsations (unless pulsatile flow is desired) to avoid unwanted fluctuations in shear stress [27].

- Cell Seeding and Adaptation: Seed primary human endothelial cells (e.g., HUVECs or iPSC-derived) into the microfluidic channel and allow them to form a confluent monolayer under static conditions for 24-48 hours.

- Application of Flow: Initiate flow at a low rate (e.g., corresponding to 1 dyne/cm²) and gradually ramp up to the target physiological shear stress over 24 hours to allow for cellular adaptation.

- Validation and Measurement:

- Computational Modeling: Use the Navier-Stokes equation to model the velocity profile and resulting shear stress within the chip geometry [27].

- Real-time Sensing: Integrate transepithelial/transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) electrodes to monitor barrier integrity in real-time under flow [28].

- Cell-based Sensors: Employ genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors that react to shear stress-induced signaling pathway activation (e.g., NF-κB or KLF2) [27].

Establishing Stable Chemical Concentration Gradients

Objective: To create stable, long-term chemical concentration gradients (e.g., of chemokines or nutrients) alongside mechanical shear stress gradients in a single microfluidic device.

Background: Immune cell migration and function are directed by chemokine gradients. Simultaneous exposure to chemical and mechanical cues more accurately represents the in vivo microenvironment that cells experience, such as in interstitial flow or during inflammatory responses [32].

Protocol for Simultaneous Gradient Generation:

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate a PDMS or polysulfone (PSF) plastic microfluidic chip containing a main culture channel and a parallel side channel for chemical introduction, connected via a porous membrane or microchannels [31] [33] [32].

- Osmotic Pump Integration: Implement an osmotic pump to generate very slow (< few µm/s), controlled flow, mimicking interstitial flow. This slow flow allows for wide and stable diffusion of chemicals, establishing a persistent concentration gradient across the cell culture chamber [31] [32].

- Passive Shear Stress Gradient: Design the main cell culture channel with a circular or varying geometry. The changing cross-section along the channel length passively creates a gradient of shear stress, with higher stress in narrower sections and lower stress in wider sections [32].

- Simultaneous Culture and Exposure: Seed cells such as L929 fibroblasts or primary endothelial cells in the main channel. Simultaneously expose the cells to the established shear stress gradient and a gradient of a chemical stimulus (e.g., a nutrient or chemokine like TNF-α) introduced from the side channel [32].

- Readout and Analysis: Assess cell alignment and mobility velocity (primarily affected by the shear stress level) and cell proliferation or differentiation (primarily reflecting the nutrient or chemical concentration level) after 24-72 hours of culture [32].

Integrating Complex Mechanical Cues in Multi-Organ Systems

Objective: To incorporate and monitor organ-specific mechanical cues, such as cyclic stretch and compression, into a multi-organ system to model integrated immune responses.

Background: Mechanical actuation is essential for realistic organ function. For example, breathing motions (cyclic stretch) in lung chips are essential for a physiological inflammatory response, and peristalsis-like motions in intestine chips create a robust barrier to bacterial infection [28].

Diagram: Integration of Mechanical Cues and Sensor Readouts in OoCs. The workflow shows how applied mechanical cues induce cellular responses that lead to measurable functional outcomes, which are quantified by integrated sensors to inform and validate the system.

Protocol for a Stretchable Lung-on-a-Chip with Immune Components:

- Chip Fabrication with Flexible Membrane: Fabricate the chip using a thin, flexible polymer membrane (e.g., PDMS or polyurethane) positioned between two microfluidic channels [33] [28].

- Cell Co-culture: Seed primary human alveolar epithelial cells on one side of the membrane and human lung microvascular endothelial cells on the other side to recreate the alveolar-capillary interface.

- Application of Cyclic Strain: Connect the side chambers of the chip to a vacuum system. Apply cyclic suction (e.g., 0.5 Hz, 10% strain) to the side chambers to rhythmically stretch the central membrane, mimicking physiological breathing motions [28].

- Introduction of Immune Components: Perfuse the endothelial channel with medium containing primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or whole blood from specific donors under physiological shear stress.

- Challenge and Readout: Expose the epithelial channel to inflammatory stimuli such as TNF-α or bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Monitor the real-time recruitment of immune cells across the endothelial and epithelial layers in response to inflammation under breathing-mimetic conditions [28] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successfully implementing the aforementioned protocols requires a specific set of reagents, cells, and hardware. The following table details key components for building immunocompetent MOCs.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Immunocompetent MOC Research

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Primary & iPSC-Derived Cells | Primary human endothelial cells (HUVEC), iPSC-derived brain microvascular endothelial-like cells, human bone marrow CD34+ cells, primary hepatocytes, EpiIntestinal cells [30] | Provide human-relevant cellular basis for organ models; enable creation of patient-specific models for precision medicine [34] [30]. |

| 3D Culture Matrices | Hydrogel scaffolds (e.g., collagen, Matrigel), 3D bioprinted composite bio-inks, 3D ceramic (hydroxyapatite) scaffolds [33] [30] | Support the formation of complex 3D tissue architectures that better mimic in vivo organ structure and function compared to 2D cultures. |

| Specialized Media & Supplements | Co-culture media, defined differentiation kits, cytokine supplements (e.g., TNF-α, interleukins) [3] [29] | Support the growth and maintenance of multiple cell types in one system and are used to induce inflammatory or differentiation states. |

| Microfluidic Chips & Consumables | PDMS-free multi-chip plates (PhysioMimix), TissUse Humimic Chips (2-, 4-organ), Emulate Organ-Chips [3] [30] | The physical platform that houses the organ models, providing perfused scaffolds and enabling microfluidic control. |

| Flow Control Systems | PhysioMimix Controller, pressure-controlled pumps, syringe pumps [3] [27] | Precisely manipulate fluid flow to generate physiological shear stress and enable inter-organ communication on-chip. |

| Integrated Sensors | TEER measurement electrodes, electrochemical sensors for metabolites, multi-electrode arrays (MEA) for electrophysiology [28] | Enable real-time, non-destructive monitoring of tissue barrier integrity, metabolic activity, and electrophysiological function. |

The advancement of immunocompetent Multi-Organ-on-Chip systems is intrinsically linked to the sophisticated integration of fluid shear stress, chemical gradients, and mechanical cues. As evidenced by the capabilities of commercial platforms and experimental protocols, these parameters are not isolated features but interdependent elements that collectively dictate the physiological fidelity of the model [26] [28]. The future of this field lies in the continued refinement of these parameters, coupled with the development of non-invasive, real-time biosensors [28] and their integration with PBPK modeling to create powerful predictive tools for drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) and toxicity [33]. Furthermore, the trend toward personalization—using patient-derived primary cells, iPSCs, and biometric data—will enable these platforms to account for individual genetic and physiological variations, ultimately accelerating the development of effective, personalized immunotherapies and more precise safety toxicology assessments [34]. By systematically implementing and validating these key design parameters, researchers can leverage MOC technology to bridge the critical gap between animal models and human clinical outcomes in immunology research.

Incorporating Innate and Adaptive Immune Cells for Systemic Response Modeling

Microphysiological systems (MPS), or organ-on-a-chip (OOC) technologies, represent a transformative approach in biomedical research by recreating human physiology in vitro. These microfluidic devices contain hollow channels lined with living human cells arranged to simulate tissue-level functions [35]. A critical advancement in this field is the incorporation of both innate and adaptive immune cells to create immunocompetent models that more accurately mimic human systemic responses [10]. The rising recognition that the immune system underpins nearly every disease pathology—from cancer and infectious diseases to autoimmune disorders—has driven innovation in this area [10]. This guide objectively compares current technologies and methodologies for modeling human immunity in MPS, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to advance their work in drug development and disease modeling.

Technology Platforms for Immune System Modeling

Commercial MPS Platforms at a Glance

Several commercial platforms now enable researchers to create immunocompetent MPS models. The table below compares key technologies and their capabilities for immune system integration.

Table 1: Commercial MPS Platforms for Immune System Modeling

| Platform Name | Manufacturer | Key Features for Immune Modeling | Throughput Capabilities | Demonstrated Immune Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVA Emulation System | Emulate [6] | 3-in-1 Organ-Chip platform; High-throughput; Automated imaging; Chip-R1 for immune cell recruitment | 96 Organ-Chip "Emulations" in a single run | Lymph Node-Chip for antigen-specific immune responses; Intestine-Chip for IBD studies |

| PhysioMimix Core | CN Bio [3] | PDMS-free plates; Adjustable recirculating flow; Open architecture for model customization | Up to 288 samples per controller unit (6 plates) | Liver and kidney safety assessment; Multi-organ crosstalk studies |

| OrganoPlate | MIMETAS [10] | 3-lane channel design; Gravity-driven flow; 64-chips per plate | 64 chips per plate | Barrier immunity models (intestine, lung, blood-brain barrier) |

| HUMIMIC Chip2 | TissUse [10] | Multi-organ capability; Up to four organ compartments connected by fluidic channels | Two or four organ compartments per chip | Systemic toxicity and ADME studies with immune components |

Technical Specifications of Featured Platforms

For researchers considering specific platforms, detailed technical specifications inform experimental design and infrastructure requirements.

Table 2: Detailed Technical Specifications of Select MPS Platforms

| Parameter | PhysioMimix Core [3] | AVA Emulation System [6] | Emulate Chip-S1/Chip-A1 [6] [10] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platform Dimensions | Controller: 230mm (W) x 430mm (D) x 415mm (H) | Combined microfluidic control, imaging, and incubation | Varies by chip type (e.g., rigid vs. stretchable chips) |

| Incubator Requirements | Standard cell culture incubator with side/rear port | Self-contained incubator | Requires external incubator |

| Multi-Organ Capability | Yes, seamless progression from single- to multi-organ | Not explicitly stated | Yes, via fluidic linking of multiple single-organ chips |

| Fluidic Flow Control | Adjustable recirculating flow rate | Precision microfluidic control | Applied mechanical forces and fluid flow |

| Throughput | Up to 6 plates (6-288 samples) per controller | 96 independent Organ-Chip samples | Lower throughput, more specialized models |

| Primary Cell Compatibility | Yes, with validated kits | Yes, as demonstrated in published applications | Yes, including patient-derived cells |

| Key Immune Application | ADME and toxicology with immune components | Lymph Node-Chip for immunotoxicity testing | Innate immune responses in Lung-Chip and Intestine-Chip |

Experimental Data from Immunocompetent MPS Models

Quantitative Assessment of Immune Responses

Recent studies have generated robust quantitative data demonstrating the functionality of immune cells within MPS. The following table summarizes key experimental findings from immunocompetent models.

Table 3: Experimental Immune Response Data from Immunocompetent MPS

| MPS Model Type | Immune Components Integrated | Challenge/Stimulus | Key Quantitative Readouts | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Airway Lung-Chip [36] | Tissue-resident macrophages, DCs, granulocytes, neutrophils, T cells, B cells, NK cells | Severe H1N1 infection (MOI 5) | • Significant cytokine storm (IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1) • Epithelial cell damage • Immune cell activation and migration | Singh et al., 2025 |

| Lymph Node-Chip [6] | Antigen-presenting cells, T cells | Antigen-specific challenge | • Predictive antigen-specific immune responses • T cell activation markers • Cytokine secretion profiles | Pfizer Data, 2025 |

| Intestine-Chip [6] | Peripheral immune cells, tissue-resident immune populations | Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) therapeutics | • Impact on goblet cells and barrier integrity • Cytokine levels • Immune cell recruitment | AbbVie Data, 2025 |

| Bone Marrow-Chip [37] | Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) | Trained immunity inducers (BCG, β-glucan) | • Epigenetic reprogramming (H3K4me3, H3K27ac) • Metabolic shifts (aerobi glycolysis) • Enhanced cytokine production | Netea et al., 2025 |

Protocol: Establishing an Immunocompetent Small Airway Lung-Chip

The following detailed methodology is adapted from Singh et al. (2025) for creating a sophisticated immunocompetent small airway lung-on-a-chip model [36].

Device Fabrication and Preparation

- Microfluidic Device: Utilize a two-channel microfluidic device separated by a porous (5.0 µm) polyester track-etched (PETE) membrane to allow immune cell migration.

- Surface Treatment: Treat the device with 0.1% pluronic F-127 for 30 minutes at room temperature to prevent non-specific cell adhesion, followed by PBS rinsing.

- Extracellular Matrix Coating:

- Airway channel: Coat with 30 µg/mL collagen IV at 37°C for 2 hours.

- Vascular channel: Coat with 100 µg/mL fibronectin at 37°C for 2 hours.

Cell Seeding and Culture

Day 0: Endothelial Network Formation

- Prepare a hydrogel solution containing human pulmonary fibroblasts (1.5 × 10^6 cells/mL) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (5 × 10^6 cells/mL) in a fibrinogen (6 mg/mL) and collagen I (1.5 mg/mL) mixture.

- Inject the hydrogel-cell mixture into the vascular channel and allow polymerization at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- Flow endothelial cell medium through the vascular channel continuously at 30 µL/hour.

Day 2: Epithelial Layer Seeding

- Seed small airway epithelial cells (SAECs) (2 × 10^6 cells/mL) into the airway channel.

- Culture submerged for 3 days with daily medium changes.

Day 5: Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) Establishment

- Drain apical medium from the airway channel to establish ALI.

- Continue feeding the vascular channel continuously and provide medium to the airway channel basolaterally only.

- Culture for 10-14 days to allow epithelial differentiation and mucociliary clearance development.

Day 14-16: Immune Cell Integration

- Tissue-resident immune cells: Introduce during hydrogel formation or after endothelial network maturation.

- Circulatory immune cells: Introduce through the vascular channel after ALI establishment, using whole blood or isolated PBMCs at physiological ratios.

Infection and Analysis

- Viral Infection: Apply H1N1 influenza virus at MOI 5 in small volume to the apical surface of the airway epithelium for 2 hours, then remove.

- Readouts and Measurements:

- Cytokine profiling: Collect effluents daily for multiplex cytokine analysis (IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, TNF-α, IFNs).

- Immunofluorescence: Fix devices and stain for cell-specific markers (CD45 for immune cells, CD31 for endothelium, TUBB4A for ciliated cells).

- Transcriptomics: Process cells for single-cell RNA sequencing to identify pathway alterations.

- Permeability assays: Measure FITC-dextran flux across the epithelial-endothelial barrier.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for establishing an immunocompetent small airway lung-on-a-chip model.

Signaling Pathways in Immunocompetent MPS

Key Immune Signaling Pathways in Influenza Infection Model

Research using immunocompetent lung-on-a-chip models has elucidated critical signaling pathways that regulate immune responses to viral infection. The following diagram illustrates the key pathways identified in severe influenza infection models [36].

Figure 2: Key immune signaling pathways in a lung-on-a-chip model of severe influenza.

Pathway Inhibition and Therapeutic Implications

Experimental manipulation of these pathways in the immunocompetent lung-chip revealed important therapeutic insights [36]:

- IL-1β inhibition: Completely ameliorated the cytokine storm, suggesting potential for severe influenza treatment.

- TNF-α inhibition: Resulted in a highly increased inflammatory response, indicating its critical regulatory role.

- CXCR4 axis inhibition: Modulated the inflammatory landscape by decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines while increasing antiviral interferons.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful establishment of immunocompetent MPS requires specific reagents and materials. The following table details essential components for modeling innate and adaptive immunity in microphysiological systems.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Immunocompetent MPS

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Immunocompetent MPS | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Cells | Small airway epithelial cells (SAECs), HUVECs, pulmonary fibroblasts | Form the foundational tissue structure and microvasculature | Source from reputable providers; maintain donor records for HLA matching [36] |

| Immune Cells | PBMCs, tissue-resident macrophages, neutrophils, T cells, B cells, DCs | Mediate immune responses and recapitulate inflammatory processes | Isate fresh or use cryopreserved vials from same donor; use HLA-matched cells when possible [10] |

| ECM Components | Collagen IV, fibronectin, fibrinogen, Matrigel | Provide structural support and biochemical cues for cell organization | Tailor composition to specific organ microenvironment [36] |

| Cell Culture Media | Endothelial cell medium, epithelial air-liquid interface medium | Support cell viability, differentiation, and function | Use specialized media formulations for different cell types; consider custom blends [36] |

| Cytokines/Chemokines | IL-1β, TNF-α, CXCL12, IFN-γ | Modulate immune cell behavior and signaling pathways | Use for controlled immune activation studies; validate concentrations [36] [37] |

| Analysis Reagents | Multiplex cytokine arrays, immunofluorescence antibodies, scRNA-seq kits | Enable quantitative assessment of immune responses | Plan analysis workflow ahead; ensure antibody compatibility with fixed chip samples [36] |

The integration of innate and adaptive immune cells into MPS represents a significant advancement in modeling human systemic responses. Current technologies from commercial providers like Emulate, CN Bio, and MIMETAS offer diverse platforms suited to different research needs, from high-throughput screening to complex multi-organ studies. Experimental data demonstrates that these immunocompetent models can recapitulate critical aspects of human immune responses, including cytokine storms, immune cell recruitment, and antigen-specific activation.

Future developments will likely focus on improving long-term immune cell viability, establishing standardized protocols for immune cell integration, and addressing the challenge of HLA matching between different cell types from various donors [10]. Additionally, the incorporation of trained immunity concepts—where innate immune cells develop memory-like characteristics through epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming—opens new avenues for modeling chronic inflammation and vaccine responses [37]. As these technologies continue to mature, immunocompetent MPS will play an increasingly vital role in drug development, personalized medicine, and fundamental immunology research.

From Theory to Therapy: Applications in Immunotherapy and Systemic Toxicology

Screening and Optimizing Cancer Immunotherapies (e.g., CAR-T, Checkpoint Inhibitors)

Cancer immunotherapy, particularly Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), has revolutionized oncology treatment by harnessing the body's immune system to combat cancer. Despite remarkable success in hematological malignancies, the development of novel immunotherapeutic agents faces persistent challenges due to poor translation from preclinical to clinical stages [38]. A significant barrier is the limited predictive value of traditional preclinical models; animal models often fail to recapitulate human immune responses due to species-specific differences, while conventional 2D in vitro cultures lack the physiological complexity of the human tumor microenvironment (TME) [9] [18].

Within this challenging landscape, human organ-on-chip (Organ-Chip) systems have emerged as a transformative technology to bridge this translational gap. These microfluidic devices are lined with living human cells cultured under fluid flow to recapitrate organ-level physiology and pathophysiology with high fidelity [9]. This review objectively compares the performance of Organ-Chip platforms against traditional models in screening and optimizing cancer immunotherapies, focusing on their experimental application, quantitative outcomes, and specific protocols that demonstrate their value in predicting human clinical responses.

Performance Comparison: Organ-Chip vs. Traditional Models

The table below summarizes a direct comparison of key performance metrics between Organ-Chip systems and traditional preclinical models, based on experimental data from published studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Preclinical Models in Cancer Immunotherapy Safety and Efficacy Assessment

| Performance Metric | Traditional 2D Models | Animal Models | Human Organ-Chip Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction of Clinical Immunotoxicity | Poor (Failed to predict FOLR1 TCB toxicity) [18] | Variable (Failed in TGN1412 trial; predicted FOLR1 TCB lung toxicity in primates) [18] [39] | High (Accurately replicated FOLR1 & CEA TCB toxicity profiles and affinity-dependent effects) [18] [40] |

| Physiological Antigen Expression | Non-physiological, altered levels and patterns [18] | Species-specific differences (e.g., human CEA not cross-reactive) [18] | Physiologically relevant (e.g., CEA expression gradient in intestine chips mimicking human tissue) [18] [40] |

| Immune Cell Recruitment & Function | Limited, lacks vascular perfusion and cell migration [39] | Intact but species-specific [38] | Demonstrated (T-cell infiltration, activation, and target-cell killing quantified on-chip) [18] |

| Throughput & Scalability | High | Low | Medium (Increasing with multi-organ systems and robotic coupling) [9] [38] |

| Key Supporting Experimental Data | Transwell cultures failed to recapitulate primate toxicity data [40] | Severe lung toxicity in primates with FOLR1(Hi) TCB [18] | Quantified epithelial cytotoxicity: ~60% (Colon) vs ~20% (Duodenum) with CEA TCB; Affinity-dependent safety profile confirmed [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Immunotherapy Evaluation on Organ-Chips

This section details the specific methodologies used to generate the comparative data, providing a toolkit for researchers to implement these models.

Protocol: Evaluating On-Target, Off-Tumor Toxicity of T-Cell Bispecific Antibodies (TCBs)

This protocol, adapted from Kerns et al. and Cabon et al., outlines the steps for assessing the safety of TCBs using human immunocompetent Organ-Chips [18] [40].

Chip Fabrication and Seeding:

- Device: Use a two-channel microfluidic device made of Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) or other polymers, separated by a porous membrane coated with extracellular matrix (e.g., collagen IV) [18].

- Tissue-Specific Cells: Seed primary human organ-specific cells (e.g., lung alveolar epithelial cells, intestinal duodenum/colon epithelial cells) in the top channel. Culture at an air-liquid interface (ALI) for lung or liquid-liquid interface for intestine to promote maturation [18] [40].

- Vascular Channel: Seed primary human microvascular endothelial cells in the bottom channel to form a vascular tube [18].

Model Maturation:

- Culture the chips for 5-14 days to allow the formation of confluent, differentiated, and functional tissue barriers. Maturity is assessed by measuring transepithelial/transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) and immunostaining for tight junction proteins [18].

Introduction of Immune Compartment:

- Isulate Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) from healthy human donors.

- Perfuse PBMCs through the vascular channel, allowing them to interact with the endothelium and, under inflammatory cues, migrate into the tissue compartment [18].

Immunotherapy Treatment:

- Introduce the therapeutic agent (e.g., FOLR1-TCB or CEA-TCB) into the vascular channel at clinically relevant concentrations. Include control groups with non-targeting antibodies [18].

Real-Time Monitoring and Endpoint Analysis:

- Cell Killing/Viability: Quantify apoptosis and cell death in the tissue layer in real-time using live-cell imaging of fluorescent dyes (e.g., caspase-3/7 reagents) or by endpoint measurement of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release [18].

- Immune Cell Activation: Collect effluent from the vascular channel and analyze by flow cytometry for T-cell activation markers (e.g., CD69, CD25) and cytokine release (e.g., IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-6) via ELISA or multiplex assays [18].

- Morphological and Barrier Function Analysis: Fix and immunostain chips for microscopy to assess tissue integrity, immune cell infiltration, and target antigen expression. Monitor barrier function via TEER throughout the experiment [18].

Protocol: Assessing CAR-T Cell Trafficking and Tumor Cell Killing

While the search results focus on TCBs, the principles can be extended to CAR-T cells, a key area of development in microfluidic models [38].

Tumor Microenvironment (TME) Compartment Setup:

- In one channel of a multi-channel chip, embed cancer cells (as a monolayer, spheroid, or patient-derived organoid) within a 3D hydrogel matrix (e.g., Matrigel, collagen) to mimic the TME [38].

Vascular Compartment Setup:

- Seed endothelial cells in an adjacent channel to form a perfusable vessel. The hydrogel and vascular channels can be separated by a membrane or directly abutted to allow for cell migration [38].

CAR-T Cell Introduction and Trafficking:

- Generate CAR-T cells specific to a tumor antigen (e.g., CD19, BCMA, or solid tumor targets like GD2 or MSLN) [41] [42].

- Perfuse fluorescently labeled CAR-T cells through the vascular channel.

- Quantify CAR-T cell adhesion to the endothelium, extravasation, and migration towards the tumor compartment using time-lapse microscopy [38].

Tumor Killing Efficacy Assessment:

- Co-culture CAR-T cells with the established tumor compartment.

- Measure tumor cell death in real-time using live-cell imaging and fluorescent viability/cell death markers.

- Analyze cytokine profiles in the effluent to assess the potency and potential cytokine release syndrome (CRS)-like activity [38].

Visualization of Experimental Workflow and Signaling

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow and key biological events in a generalized immunocompetent Organ-Chip model for immunotherapy testing.

Figure 1: Workflow for Evaluating Immunotherapies on Organ-Chips. This diagram outlines the key steps, from chip establishment to quantitative endpoint analysis, for assessing both efficacy and on-target, off-tumor toxicity.

The diagram below details the molecular mechanism of action of a T-cell engaging bispecific antibody (TCB) within the Organ-Chip, leading to either intended tumor cell killing or unintended on-target, off-tumor toxicity in healthy tissue.

Figure 2: Mechanism of TCB-Mediated Target Cell Killing. The TCB crosslinks the CD3 complex on T-cells with a Tumor-Associated Antigen (TAA) on a target cell, triggering T-cell activation and cytotoxic killing of the target cell, which can be either a tumor cell (desired) or a healthy cell expressing the TAA (on-target, off-tumor toxicity).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and reagents used in the featured Organ-Chip experiments, providing a practical resource for protocol implementation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Organ-Chip Immunotherapy Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Human Cells | Recreate organ-specific parenchyma and vasculature with human-specific biology. | Lung alveolar epithelial cells, intestinal epithelial cells, lung microvascular endothelial cells [18]. |

| Hydrogel Matrix | Provide a 3D scaffold to support cell growth and mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM). | Collagen IV, Matrigel [18]. |

| Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | Source of human immune cells (T-cells, NK cells, monocytes) for immunocompetence. | Isolated from healthy human donor blood [18]. |

| T-Cell Bispecific Antibodies (TCBs) | Engineered immunotherapeutics to test efficacy and safety. | FOLR1-targeting TCB, CEA-targeting TCB, with high- and low-affinity variants [18] [40]. |

| Microfluidic Device | Platform housing the living cellular model and enabling controlled perfusion. | PDMS-based chips with two parallel channels separated by a porous membrane [9] [18]. |

| Cell Viability/Cytotoxicity Assays | Quantify target cell death and overall tissue health. | Live-cell imaging with caspase-3/7 reagents, Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) release assays [18]. |

| Cytokine Detection Kits | Measure immune cell activation and potential for cytokine release syndrome (CRS). | ELISA, multiplex bead-based arrays for IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8 [18]. |

The experimental data and protocols detailed herein demonstrate that human immunocompetent Organ-Chip systems offer a quantitatively superior and more physiologically relevant platform for screening and optimizing cancer immunotherapies compared to traditional models. Their proven ability to recapitulate on-target, off-tumor toxicities, predict affinity-dependent safety profiles, and model human-specific immune responses positions this technology as a critical tool for de-risking drug candidates prior to clinical trials [18] [40]. As the field advances, the integration of multiple organ systems into a "human-on-a-chip" represents the next frontier, promising a holistic, systemic view of immunotherapy efficacy and safety that could fundamentally accelerate and improve the drug development process [9] [39].

Modeling ADME and Pharmacokinetics (PK/PD) in Connected Organ Systems

The high failure rate of drug candidates in clinical trials, often due to unforeseen human Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) and toxicity profiles, underscores a critical inadequacy in conventional preclinical models [9] [1]. Traditional 2D cell cultures cannot replicate organ-level physiology, while animal models frequently suffer from species-specific differences that limit their predictive power for human responses [30] [1]. Microphysiological Systems (MPS), often called Multi-Organ-on-a-Chip (MOC), have emerged as a transformative technology designed to bridge this gap. These microfluidic devices culture living, functional human tissues in fluidically connected chambers, recapitulating the dynamic organ-organ crosstalk essential for accurate modeling of systemic drug disposition and pharmacological effects [43] [44] [45]. By replicating a human pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) model in vitro, MOCs offer a powerful platform for predicting a drug's journey through the body and its ultimate effect on its target [33] [45].

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Organ-on-Chip Platforms for ADME/PK

Various MOC platforms have been developed and validated to study specific ADME and PK/PD pathways. The table below summarizes key assays, their configurations, and their primary applications in drug development.

Table 1: Comparison of Validated Multi-Organ-on-Chip Assays for ADME/PK Modeling

| Organ Model | Key Organs Included | Primary ADME/PK Application | Notable Features & Validated Compounds | Supporting In Vivo Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|